Abstract

A major difference between vaccine and wild-type strains of measles virus (MV) in vitro is the wider cell specificity of vaccine strains, resulting from the receptor usage of the hemagglutinin (H) protein. Wild-type H proteins recognize the signaling lymphocyte activation molecule (SLAM) (CD150), which is expressed on certain cells of the immune system, whereas vaccine H proteins recognize CD46, which is ubiquitously expressed on all nucleated human and monkey cells, in addition to SLAM. To examine the effect of the H protein on the tropism and attenuation of MV, we generated enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-expressing recombinant wild-type MV strains bearing the Edmonston vaccine H protein (MV-EdH) and compared them to EGFP-expressing wild-type MV strains. In vitro, MV-EdH replicated in SLAM+ as well as CD46+ cells, including primary cell cultures from cynomolgus monkey tissues, whereas the wild-type MV replicated only in SLAM+ cells. However, in macaques, both wild-type MV and MV-EdH strains infected lymphoid and respiratory organs, and widespread infection of MV-EdH was not observed. Flow cytometric analysis indicated that SLAM+ lymphocyte cells were infected preferentially with both strains. Interestingly, EGFP expression of MV-EdH in tissues and lymphocytes was significantly weaker than that of the wild-type MV. Taken together, these results indicate that the CD46-binding activity of the vaccine H protein is important for determining the cell specificity of MV in vitro but not the tropism in vivo. They also suggest that the vaccine H protein attenuates MV growth in vivo.

INTRODUCTION

Measles remains a major cause of childhood morbidity and mortality worldwide especially in developing countries in spite of significant progress in global measles control programs. Measles virus (MV), belonging to the genus Morbillivirus of the family Paramyxoviridae, is an enveloped virus with a nonsegmented negative-strand RNA genome (11). The MV genome encodes 6 structural proteins: the nucleocapsid (N), phospho (P), matrix (M), fusion (F), hemagglutinin (H), and large (L) proteins. Two envelope glycoproteins, the F and H proteins, initiate infection of the target cells via binding of the H protein to its cellular receptors. Therefore, the H protein is of primary importance for determining the cell specificity of MV (22).

The Edmonston strain of MV was isolated in 1954 by using a primary culture of human kidney cells (7). The Edmonston strain was subsequently adapted in a variety of cells, including chicken embryo fibroblasts, to enable the production of attenuated live vaccines, which are currently used worldwide (27). These live, attenuated MV strains are safe and induce strong cellular and humoral immune responses against MV. The Edmonston vaccine strain is no longer pathogenic in monkey models (2, 7, 37, 39). In contrast, wild-type MV strains isolated and passaged in B95a cells induce clinical signs resembling those of human measles in experimentally infected cynomolgus and rhesus monkeys (15, 16).

A major difference between vaccine and MV wild-type strains in vitro is their cell specificity. Vaccine strains of MV grow efficiently in many human and primate cell lines, whereas wild-type strains of MV grow only in limited lymphoid cell lines. This difference is attributed mainly to the receptor usage of MV strains. The H proteins of wild-type strains recognize the signaling lymphocyte activation molecule (SLAM) (also called CD150), which is expressed in certain immune system cells (36), and the recently identified nectin-4 (also called PVRL4), which is expressed in epithelial cells in trachea, skin, lung, prostate, and stomach as a cellular receptor (20, 23). However, the H proteins of MV vaccine strains recognize CD46 (6, 21) in addition to SLAM and nectin-4 as cellular receptors. Since CD46 is expressed in all human and monkey nucleated cells, MV vaccine strains can grow in many human and primate cell lines. Indeed, when the H protein of a wild-type strain of MV was exchanged with that of an MV vaccine strain, the resulting recombinant wild-type MV strain grew in many human and monkey cell lines (12, 28, 35).

Although the receptor specificity of the H proteins of MV strains has been studied extensively, very little is known about the effect of the H protein on the in vivo tropism and attenuation of MV. Given that the H proteins of MV vaccine strains can use CD46 in addition to SLAM and nectin-4 as cellular receptors, recombinant MV strains bearing the H protein of MV vaccine strains may have an expanded in vivo tropism.

In this study, we generated enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-expressing recombinant wild-type strains of MV bearing the H protein of the Edmonston MV vaccine strain by using our reverse genetics system (32) and compared the cell specificity in vitro and tropism in vivo with those of EGFP-expressing MV wild-type strains. We found that the H protein of the Edmonston vaccine strain of MV alters the cell specificity of the MV wild-type strain in vitro but does not alter the tropism of the MV wild-type strain in vivo. Furthermore, the H protein of the Edmonston vaccine strain attenuates MV growth in macaques.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

B95a cells (an adherent marmoset B-cell line transformed with Epstein-Barr virus) (15) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified essential medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells constitutively expressing human SLAM (CHO/hSLAM) (29) were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 500 μg of G418 per ml. Primary cynomolgus monkey astroglial cells were obtained from Nobuyuki Kimura (National Institute of Biomedical Innovation, Tsukuba, Japan). IC323-EGFP was obtained from Yusuke Yanagi (Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan) (12). Vaccinia virus vTF7-3 encoding T7 RNA polymerase was obtained from Bernard Moss (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) (9).

Preparation of primary cynomolgus monkey kidney cells.

The kidneys of a cynomolgus monkey were removed, sliced into small pieces, and digested with 0.3% trypsin in Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBBS) at 37°C with continuous stirring for an appropriate period. The dispersed cells were collected and washed twice with HBBS. The cells were suspended in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, seeded on a plate, and incubated at 37°C. Cells that grew as a monolayer culture were passaged, and the cells at passages 3 to 5 were used in the experiments.

Construction of full-length cDNAs and reverse genetics.

Plasmid p(+)MV323, carrying the full-genome cDNA of the IC-B strain, has been described previously (15, 32, 33). Plasmid p(+)MV017, carrying the full-genome cDNA of the IC-B strain containing the H gene of the Edmonston B strain (Z66517), has been described previously (35). To exchange the H gene of p(+)MV323-EGFP with that of the Ed strain, a PacI-SpeI fragment containing the H gene was excised from p(+)MV323-EGFP and replaced with the corresponding fragment from p(+)MV017, resulting in p(+)MV017-EGFP. To introduce the EGFP gene between the F and H genes of p(+)MV323 and p(+)MV017, the open reading frame of an enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) gene was first amplified from pEGFP-N1 (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) by using the primers 5′-ATCAGGGACAAGAGCAGGATTAGGGATATCCGAGATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGGA-3′ and 5′-GATGTTGTTCTGGTCCTCGGCCTCTCGCACTTACTTGTACAGCTCGTCCA-3′ and then using the primers 5′-GCGTTAATTAAAACTTAGGATTCAAGATCCTATTATCAGGGACAAGAGCAGGAT-3′ and 5′-GCGTTAATTAACAATGATGGAGGGTAGGCGGATGTTGTTCTGGTCCTCGG-3′ to introduce a PacI recognition site (underlined). After digestion with PacI, the EGFP fragment was inserted into the PacI sites in p(+)MV323 and p(+)MV017, resulting in p(+)MV323-EGFP(F/H) and p(+)MV017-EGFP(F/H), respectively. Recombinant MV strains EdH-EGFP, IC323-EGFP2 and EdH-EGFP2 were generated from the p(+)MV017-EGFP, p(+)MV323-EGFP(F/H), and p(+)MV017-EGFP(F/H) plasmids, respectively, by using CHO/hSLAM cells and vaccinia virus vTF7-3 as reported previously (29). IC323-EGFP, EdH-EGFP, IC323-EGFP2, and EdH-EGFP2 were propagated in B95a cells, and virus stocks at 3 to 4 passages in B95a cells were used for experiments. The amino acid sequence of the F protein of the IC-B strains (NC_001498/AB016162) is identical to that of the F protein of the Edmonston-B strain (Z66517).

Infection of cynomolgus monkeys with recombinant MVs.

Cynomolgus monkeys were inoculated intranasally with 105 times the 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) of IC323-EGFP2 or EdH-EGFP2 by using a nasal spray (Keytron, Chiba, Japan). Three animals (no. 4848, 4849, and 4850) were juvenile (1 year old), and 6 animals (no. 5056, 5057, 5058, 5062, 5068, and 5069) were 4 to 5 years old. All animals were seronegative for MV. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated using a Percoll gradient (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) diluted with a 1.5 M NaCl solution to 1.07 g/ml. MV-infected cells in PBMCs, spleens, and cervical lymph nodes were counted as previously reported (32). All animal experiments were performed in compliance with the guidelines of National Institute of Infectious Disease (Tokyo, Japan).

Macroscopic detection of EGFP fluorescence.

EGFP fluorescence in the tissues and organs of cynomolgus monkeys was observed using a VB-G25 fluorescence microscope equipped with a VB-7000/7010 charge-coupled device (CCD) detection system (Keyence, Osaka, Japan). For the respective excitation and the detection of fluorescence, 470/40-nm and 510-nm band-pass filters were used.

Histopathological and immunohistochemical analysis.

Animals were anesthetized, and tissues from lung, bronchus, heart, liver, kidney, skin, spleen, mesenteric lymph node (MLN), cervical lymph node, thymus, salivary gland, tonsil, stomach, pancreas, and jejunum were fixed with 10% phosphate-buffered formalin. Fixed tissues were embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Immunohistochemical detection of the N protein of MV was performed on paraffin-embedded sections as described previously (34).

Double immunofluorescence staining.

Paraffin-embedded lungs were used for staining the N protein of MV and cytokeratin. The sections were subjected to a double immunofluorescence staining method employing a rabbit antiserum against the N protein and the cytokeratin monoclonal mouse antibody (clone MAB1611; Chemicon, CA). Briefly, after deparaffinization with xylene, the sections were rehydrated in ethanol and immersed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Antigens were retrieved by hydrolytic autoclaving for 15 min at 121°C in the retrieval solution at pH 9.0 (Nichirei, Tokyo, Japan). After cooling, normal goat serum was used to block background staining. The sections were incubated with the anticytokeratin antibody for 30 min at 37°C. After 3 washes in PBS, the sections were incubated with an antiserum against MV N protein for 30 min at 37°C. Antigen-binding sites were detected with goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) or goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 546 (Molecular Probes) for 30 min at 37°C. The sections were mounted with SlowFade Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole) (Molecular Probes), and the images were captured using a fluorescence microscope (IX71; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a Hamamatsu high-resolution digital B/W CCD camera (ORCA2; Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan).

Flow cytometric analysis.

PBMCs were stained with the following monoclonal antibodies, which are cross-reactive with macaque cells: CD150-phycoerythrin (PE) clone A12 (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), CD3-allophycocyanin (APC) clone SP34-2 (BD Pharmingen), and CD20-PE/Cy7 clone 2H7 (BioLegend, San Diego, CA). The cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde, and MV-infected cells were detected by the expression of EGFP in the fluorescein isothiocyanate channel. The flow cytometric acquisition of approximately 200,000 to 500,000 events from each sample was performed on a FACSCalibur instrument.

Amplification of MV genomic RNA by real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR).

Total RNA was isolated from tissues by using the RNAlater and RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol, reverse transcribed, and PCR amplified with a Dice TP800 thermal cycler (Takara, Tokyo, Japan) by using FastStart SYBR green Master (Roche). For amplification of the MV genome sequence, MV-P1 primer 5′-AGATGCTGACTCTATCATGG-3′ (positions 2178 to 2197) was used for RT, and then MV-P1 primer and MV-P2 primer 5′-TCGAGCACATTGGGTTGCAC-3′ (positions 2574 to 2555) were used for PCR. For amplification of the 18S RNA segment, the 18S sense primer TCAAGAACGAAAGTCGGAGG and 18S antisense primer GGACATCTAAGGGCATCACA (25) were used. In a separate experiment, we amplified DNA from a known amount of p(+)MV323-EGFP plasmid containing the target region under the same reaction conditions, and the results for the real-time RT-PCR were expressed as genome RNA equivalent to p(+)MV323-EGFP.

Cytokine assay.

Cytokine levels in the plasma were measured with a Luminex 200 instrument (Luminex, Austin, TX) by using a Milliplex nonhuman primate cytokine/chemokine kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The assay sensitivities were as follows; interleukin-12/23 (IL-12/23) (p40), 1.11 pg/ml; gamma interferon (IFN-γ), 0.30 pg/ml; IL-2, 0.73 pg/ml; IL-4, 1.25 pg/ml; IL-5, 0.26 pg/ml; IL-17, 0.13 pg/ml; IL-6, 0.40 pg/ml; tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), 0.86 pg/ml; IL-1β, 0.16 pg/ml; and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1), 0.91 pg/ml.

RESULTS

Generation of recombinant MV strains expressing EGFP.

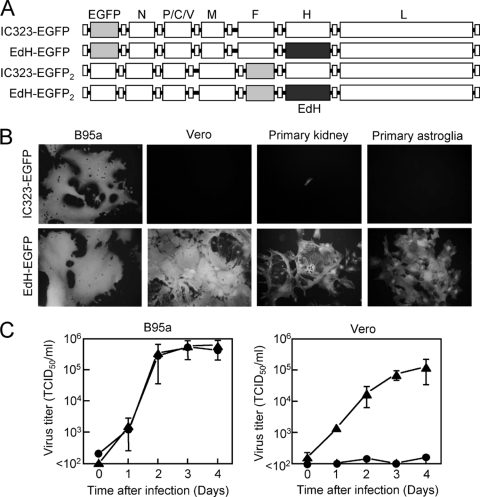

To compare the cell specificities in vitro of wild-type MV and wild-type MV bearing the H protein of the Edmonston vaccine strain, we generated EdH-EGFP from wild-type IC323-EGFP (12). IC323-EGFP and EdH-EGFP (Fig. 1A) have the EGFP gene preceding the N gene and induce a strong EGFP fluorescence in infected monolayer cells. For in vivo infection, we generated IC323-EGFP2 and EdH-EGFP2 (Fig. 1A), having the EGFP gene between the F and H genes, because a previous report using canine distemper virus (CDV) indicated that a CDV strain having the EGFP gene preceding the N gene had reduced overall CDV gene expression and was less virulent (38). IC323-EGFP2 and EdH-EGFP2 induced very weak EGFP fluorescence in infected monolayer cells (data not shown) because of the polar effect of paramyxovirus transcription (17).

Fig 1.

Generation, dissemination, and growth of recombinant measles virus (MV) having the hemagglutinin (H) protein of the Edmonston vaccine strain. (A) Schematic diagram of the genomic organizations of IC323-EGFP, EdH-EGFP, IC323-EGFP2, and EdH-EGFP2. (B) B95a, Vero, primary cynomolgus monkey kidney, and primary cynomolgus monkey astroglial, cells were infected with IC323-EGFP or EdH-EGFP. The MV-infected cells were visualized with EGFP autofluorescence at day 2 (B95a), day 3 (Vero), day 4 (primary kidney), or day 3 (primary astroglia). (C) Replication kinetics of IC323-EGFP2 and EdH-EGFP2. B95a cells and Vero cells were infected with IC323-EGFP2 (circles) or EdH-EGFP2 (triangles) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01 tissue culture infective dose (TCID50)/cell. Cells and media were harvested at days 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4, and infectivity titers were assessed as TCID50 using B95a cells.

Infection of primary cell culture with recombinant MV strains.

We first examined the cell specificities of IC323-EGFP and EdH-EGFP in vitro. In B95a cells, both IC323-EGFP and EdH-EGFP induced large syncytia and strong EGFP expression, whereas in Vero cells, only EdH-EGFP induced syncytia and strong EGFP expression (Fig. 1B), consistent with our previous observation (35). Notably, EdH-EGFP induced large syncytia and strong EGFP expression in primary kidney and primary astroglial cells derived from cynomolgus monkey tissues (Fig. 1B). Thus, the H protein of the Edmonston vaccine strain of MV can expand the in vitro cell specificity of the wild-type MV strain in established cell lines as well as in primary cell cultures of cynomolgus monkey tissues.

Preliminary infection of cynomolgus monkeys with recombinant MV strains.

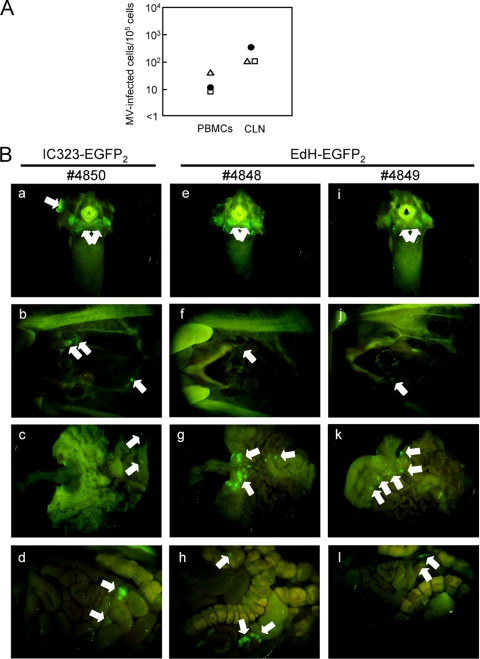

We next examined the in vivo tropism and growth of IC323-EGFP2 and EdH-EGFP2 by using 3 cynomolgus monkeys. Prior to the infection of monkeys with IC323-EGFP2 and EdH-EGFP2, we examined the in vitro cell specificities of the two strains by using B95a and Vero cells and confirmed that EdH-EGFP2 had the wider in vitro cell specificity (Fig. 1C). Then, one monkey (no. 4850) was inoculated with IC323-EGFP2, and two monkeys (no. 4848 and 4849) were inoculated with EdH-EGFP2. At day 7, viremia was observed in all 3 monkeys (Fig. 2A). Upon necropsy at day 7, nearly the same numbers of MV-infected cells were isolated from the cervical lymph nodes of the 3 monkeys (Fig. 2A). EGFP fluorescence was observed in many lymphoid tissues, including the cervical lymph nodes, tongue, tonsils, stomach, and gut-associated lymph nodes, in the 3 monkeys (Fig. 2B). No significant difference in the distributions and intensities of EGFP fluorescence in the internal organs and tissues was observed among the 3 monkeys, indicating that the tropism of EdH-EGFP2 was not expanded in vivo.

Fig 2.

Detection of MV-infected cells in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and cervical lymph nodes and EGFP expression in the tissues and organs of infected macaques. (A) One monkey (no. 4850) (closed circles) was infected with IC323-EGFP2 and 2 monkeys (no. 4848 and 4849) (open triangles and open squares, respectively) were infected with EdH-EGFP2. Single-cell suspensions (105/ml) from PBMCs and cervical lymph nodes (CLN) were divided into 2-fold serial dilutions, and then a 1-ml aliquot of each diluted single-cell suspension was inoculated into subconfluent B95a cells on 24-well cluster plates in duplicate. The number of MV-infected cells per 105 single-cell suspensions was then calculated. (B) At day 7, EGFP fluorescence in the tongue and tonsils (a, e, and i), cervical lymph nodes (b, f, and j), stomach (c, g, and k), and gut-associated lymph nodes (d, h, and l) was detected using a fluorescence microscope with a charge-coupled device (CCD) camera. Arrows indicate the MV-infected regions expressing EGFP.

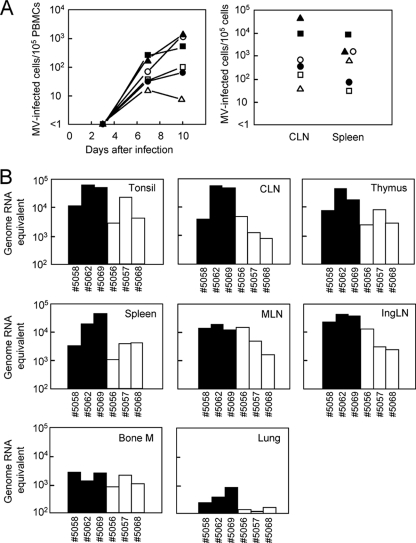

Growth of recombinant MV strains in cynomolgus monkeys.

To assess whether these results could be confirmed, 6 monkeys were infected with IC323-EGFP2 or EdH-EGFP2. Three monkeys (no. 5058, 5062, and 5069) were inoculated with IC323-EGFP2, and 3 monkeys (no. 5056, 5057, and 5068) were inoculated with EdH-EGFP2. At day 7, viremia was detected in all 6 monkeys, and the number of infected cells was increased at day 10 in most monkeys (Fig. 3A, left). Upon necropsy at day 10, MV-infected cells were isolated from the cervical lymph nodes and spleens of the 6 monkeys (Fig. 3A, right). In monkeys infected with IC323-EGFP2 a large number of the lymphocytes (up to 49%) of cervical lymph nodes were infected, whereas in monkeys infected with EdH-EGFP2, a smaller number (0.040 to 0.77%) of the lymphocytes of cervical lymph nodes were infected (Fig. 3A, right). Similarly, in monkeys infected with IC323-EGFP2, a large number of the lymphocytes (up to 8.2%) in the spleen were infected, whereas in monkeys infected with EdH-EGFP2, a smaller number (0.032 to 1.5%) of the lymphocytes in cervical lymph nodes were infected (Fig. 3A, right). In all 6 monkeys infected with either IC323-EGFP2 or EdH-EGFP2, substantial amounts of MV genome RNA were detected in the tonsils, cervical lymph nodes, thymus, spleen, mesenteric lymph nodes, inguinal lymph nodes, bone marrow, and lungs (Fig. 3B). We note that the amount of MV genome RNA in EdH-EGFP2-infected monkeys was significantly lower than that in IC323-EGFP2-infected monkeys, especially in lungs.

Fig 3.

Detection of MV-infected cells and MV genome RNA. (A) Three monkeys (no. 5058, 5062, and 5069) (closed circles, closed triangles, and closed squares, respectively) were infected with IC323-EGFP2, and 3 monkeys (no. 5056, 5057, and 5068) (open circles, open triangles, and open squares, respectively) were infected with EdH-EGFP2. PBMCs were obtained at days 3, 7, and 10. CLN and spleens were obtained on day 10. Single-cell suspensions (105/ml) from PBMCs, CLN, and spleen were divided into 2-fold serial dilutions, and then a 1-ml aliquot of each diluted single-cell suspension was inoculated into subconfluent B95a cells on 24-well cluster plates in duplicate. The number of MV-infected cells per 105 single-cell suspensions was then calculated. (B) MV genome RNA was detected by real-time reverse transcription-PCR on total RNA isolated from tonsils, CLN, thymus, spleens, mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN), inguinal lymph nodes (IngLN), bone marrow (bone M), and lungs. Three monkeys (no. 5058, 5062 and 5069) were infected with IC323-EGFP2, and 3 monkeys (no. 5056, 5057, and 5068) were infected with EdH-EGFP2. The results for the real-time RT-PCR were expressed as genome RNA equivalent to plasmid p(+)MV323-EGFP.

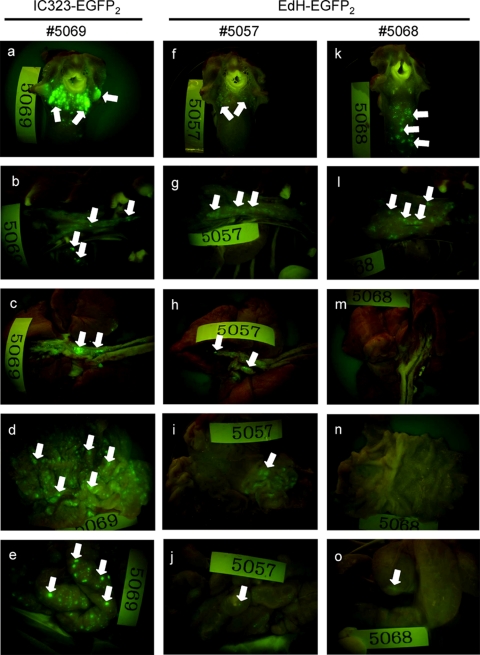

Macroscopic detection of EGFP fluorescence in organs and tissues.

In all 6 monkeys infected by IC323-EGFP2 or EdH-EGFP2, EGFP fluorescence was macroscopically detected in many lymphoid organs and tissues, including the tongue and tonsils, thymus, trachea and lungs, stomach, and gut-associated lymph nodes, upon necropsy at day 10 (Fig. 4). No difference in the distribution of EGFP fluorescence in the internal organs and tissues was observed between monkeys infected with IC323-EGFP2 or EdH-EGFP2, confirming that tropism of EdH-EGFP2 is not expanded in macaques. However, the intensity of EGFP fluorescence in the internal organs and tissues of EdH-EGFP2-infected monkeys was significantly weaker than that in IC323-EGFP2-infected monkeys.

Fig 4.

EGFP expression in tissues of monkeys after experimental infection with IC323-EGFP2 and EdH-EGFP2. At day 10, EGFP fluorescence in the tongue and tonsils (a, f, and k), thymus (b, g, and l), trachea and lung (c, h, and m), stomach (d, i, and n), and gut-associated lymph nodes (e, j, and o) of infected monkeys was detected using a fluorescence microscope with a CCD camera.

Histopathological and immunohistochemical analyses.

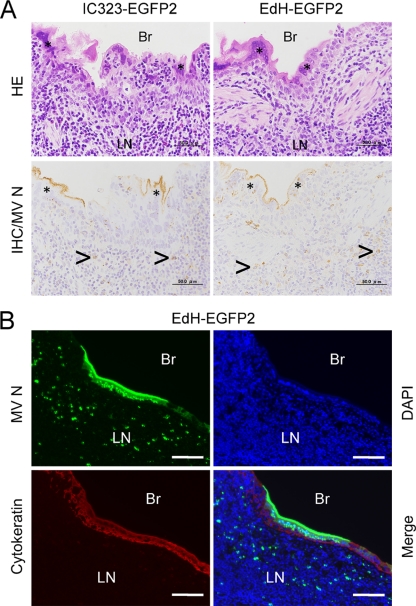

To further examine the tissue and organ tropism of IC323-EGFP2 and EdH-EGFP2, we performed histopathological and immunohistochemical analyses of fixed specimens. In bronchioles, we histopathologically observed bronchiolitis and giant cells with eosinophilic inclusion bodies in monkeys infected with both IC323-EGFP2 and EdH-EGFP2, and MV N antigen was detected in both sections (Fig. 5A). Tissue sections obtained from the bronchiole area were double stained with anti-MV N and anticytokeratin antibodies, which clearly showed infection of EdH-EGFP2 in the epithelial cells (Fig. 5B) as reported for wild-type MV (3, 20), possibly through a nectin-4-mediated pathway (18, 20, 23, 31). Interestingly, the N protein was accumulated under the apical plasma membrane of the infected cells (Fig. 5B), suggesting an intracellular mechanism of transport of the N protein to the apical plasma membrane. The MV N antigen was detected in the lymphocytes of the spleen, mesenteric and cervical lymph nodes, thymus, salivary gland, tonsils, stomach, and jejunum (Table 1), as well as in epithelia of the lungs, bronchi, tonsils, and stomach, but not in the muscles of the heart and in the epithelia of the liver, kidney, skin, tonsils, and stomach of most monkeys. These data again indicated that tropism of EdH-EGFP2 was not expanded in macaques.

Fig 5.

Histopathological and immunohistochemical analyses. (A) Bronchiole sections obtained from monkeys infected with IC323-EGFP2 or EdH-EGFP2 were examined by hematoxylin and eosin staining and immunohistochemistry. Giant-cell formation (*) and lymphoid filtrates were seen in the epithelial layer of the bronchiole. MV nucleocapsid (N) antigen (light brown) was detected in the cytoplasm and nucleus in the giant cells and in the cytoplasm of the lymphocytes (arrows) of lymphatic nodules under the epithelial layer by immunohistochemical analysis (IHC). (B) The bronchiole area obtained from a monkey infected with EdH-EGFP2 was investigated by double immunofluorescence staining. Tissue sections were stained with antiserum against the MV N antigen and mouse monoclonal antibody against cytokeratin. DAPI was used to identify nuclei. Br, bronchiole; LN, lymphatic nodule. Bars, 50 μm (A) and 100 μm (B).

Table 1.

Detection of giant cells and measles virus nucleocapsid antigen in different tissues by immunohistochemistry

| Organ | Tissue or cell type | Detection of giant cells or antigens after: |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC323-EGFP2 infection of monkey no.: |

EdH-EGFP2 infection of monkey no.: |

||||||||||||

| 5058 |

5062 |

5069 |

5056 |

5057 |

5068 |

||||||||

| Giant cells | Viral antigens | Giant cells | Viral antigens | Giant cells | Viral antigens | Giant cells | Viral antigens | Giant cells | Viral antigens | Giant cells | Viral antigens | ||

| Lung | Epithelium | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Bronchus | Epithelium | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| Heart | Muscle | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Liver | Epithelium | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Kidney | Epithelium | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − |

| Skin | Epithelium | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + |

| Spleen | Lymphocyte | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| Mesenteric lymph node | Lymphocyte | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Cervical lymph node | Lymphocyte | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Thymus | Lymphocyte | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Salivary gland | Lymphocyte | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + |

| Tonsil | Epithelium | NEa | NE | + | + | + | + | + | + | NE | NE | + | + |

| Lymphocyte | NE | NE | + | + | + | + | + | + | NE | NE | + | + | |

| Stomach | Epithelium | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + |

| Lymphocyte | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | |

| Pancreas | Epithelium | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Jejunum | Lymphocyte | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + |

NE, not examined.

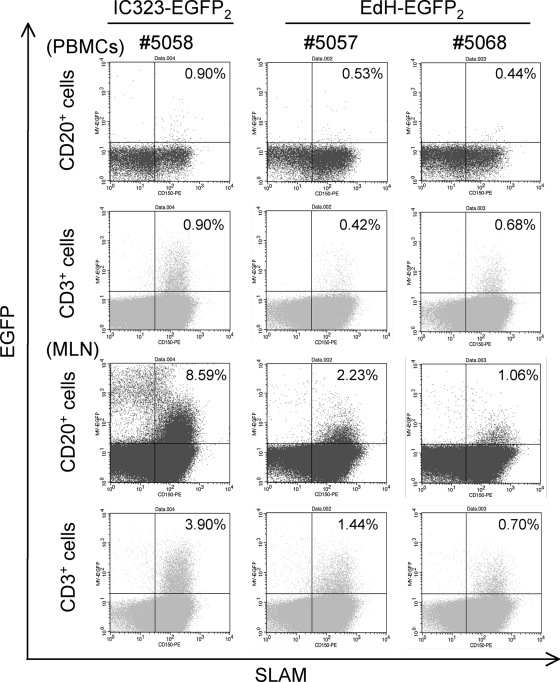

Flow cytometric analysis.

To examine the cell tropism of IC323-EGFP2 and EdH-EGFP2 in lymphocytes, EGFP expression in lymphocytes isolated from PBMCs and mesenteric lymph nodes was analyzed by flow cytometry. A total of 0.90% and 8.59% of B lymphocytes in PBMCs and MLNs, respectively, and 0.90% and 3.90% of T lymphocytes in PBMCs and MLNs, respectively, were infected with IC323-EGFP2 (Fig. 6). Lymphocytes expressing SLAM were infected with IC323-EGFP2, as previously reported (3). Similarly, 0.44 to 0.53% and 1.06 to 2.23% of B lymphocytes in PBMCs and MLNs, respectively, and 0.42 to 0.68% and 0.70 to 1.44% of T lymphocytes in PBMCs and MLNs, respectively, were infected with EdH-EGFP2 (Fig. 6). Lymphocytes expressing SLAM were also infected with EdH-EGFP2. These results indicated that tropism of EdH-EGFP2 was not expanded in lymphocytes of macaques. Interestingly, the number and intensity of EGFP-expressing cells in lymphocytes of EdH-EGFP2-infected monkeys were significantly lower than those in of IC323-EGFP2-infected monkeys.

Fig 6.

EGFP-positive cells in lymphocyte subpopulations of PBMCs and mesenteric lymph nodes from infected monkeys. Cryopreserved PBMCs and mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) of monkeys infected with IC323-EGFP2 (no. 5058) or EdH-EGFP2 (no. 5057 and 5068) were stained with monoclonal antibodies against CD3, CD20, and CD150 (signaling lymphocyte activation molecule [SLAM]) and analyzed with a FACSCalibur instrument. Results are shown as dot plots, with SLAM expression on the x axis and EGFP expression on the y axis. EGFP expression in CD20+ B lymphocytes and CD3+ T lymphocytes is shown. CD46 expression in lymphocytes of PBMCs of monkeys infected with EdH-EGFP2 (no. 5057 and 5068) was detected with monoclonal antibody against CD46 and isotype control antibody.

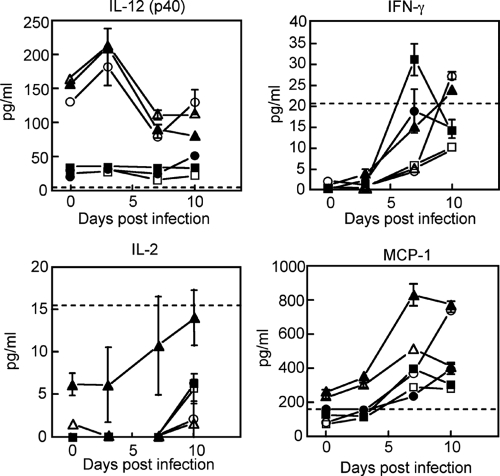

Cytokine production by infected monkeys.

To investigate whether the differences in growth of IC323-EGFP2 and EdH-EGFP2 in monkeys were associated with altered host responses to infection, we measured cytokine and chemokine levels in plasma samples from infected monkeys. The cytokines selected for analysis were IL-12, IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, and IL-17 (Th1/Th2 balance) and the IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, and MCP-1 (inflammatory response).

With Th1-type cytokines, we found that plasma levels of IL-12 were high for 3 (no. 5056, 5057, and 5062) out of 6 monkeys at day 0, were slightly elevated at day 3, and then declined by day 7 (Fig. 7). The plasma levels of IL-12 for the 3 other monkeys (no. 5058, 5068, and 5069) were low throughout the experiment. Irrespective of the plasma levels of IL-12, the plasma levels of IFN-γ were elevated in all 6 monkeys. The increase in plasma levels of IL-2 was marginal by day 10 for 5 monkeys. For inflammatory cytokines, the plasma level of MCP-1 was markedly elevated for all monkeys. IL-4, IL-17, and IL-1β were not detected throughout the experiment. Other cytokines (IL-5, IL-6, and TNF-α) were not consistently detected (data not shown).

Fig 7.

Detection of cytokines in plasma samples from infected monkeys. Three monkeys (no. 5058, 5062, and 5069) (closed circles, closed triangles, and closed squares, respectively) were infected with IC323-EGFP2. Three other monkeys (no. 5056, 5057, and 5068) (open circles, open triangles, and open squares, respectively) were infected with EdH-EGFP2. Plasma was obtained at days 0, 3, 7, and 10. Cytokine levels in the plasma were measured with a Luminex 200 instrument using a Milliplex nonhuman primate cytokine/chemokine kit. The physiological upper concentration ranges detected in human plasma are indicated by dotted lines.

Taking the results together, there were no significant differences in the cytokine production profiles of the monkeys infected with IC323-EGFP2 or EdH-EGFP2, and similar Th1-type and inflammatory responses against acute MV infection occurred in monkeys infected with IC323-EGFP2 or EdH-EGFP2.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we compared the cell specificities and tropisms of the wild-type strains of MV bearing the H protein of the Edmonston vaccine strain with those of the wild-type MV strains. Although EdH-EGFP showed wider cell specificity in cell lines and primary cell cultures (Fig. 1B), the tissue and organ tropism of EdH-EGFP2 was not altered in all 5 infected macaques (Fig. 2 and 4 and Table 1). Since CD46 is ubiquitously expressed in human and monkey cells, EdH-EGFP2 could infect all cells in macaques. However, widespread infection of EdH-EGFP2 in tissues and organs was not observed. This result is not surprising because it was reported that only the lymph nodes and spleen of monkeys were infected with MV vaccine strains (39). Furthermore, it was recently reported that CD11c-positive myeloid cells, such as alveolar macrophages and dendritic cells in lungs of monkeys, were infected with an EGFP-expressing recombinant Edmonston strain of MV via an aerosol route (5). This result is consistent with our findings in that the CD46-using Edmonston vaccine strain does not cause widespread infection in the lungs of monkeys, although there is a possibility that the infection by the Edmonston strain in lungs may be restricted due to mutations in the N and P/C/V genes, which are most important in combating the innate immune system.

One possible explanation for the limited infection of EdH-EGFP2 in macaques is the expression level of CD46. Anderson et al. reported that at low CD46 density, infection with the MV vaccine strain occurs but subsequent cell-to-cell fusion does not (1). If the expression levels of CD46 are low in cells in the tissues, EdH-EGFP2 may infect those cells, but subsequent cell-to-cell fusion may not occur. In primary cell cultures, gene expression profiles often change when tissue cells are cultured in vitro. Thus, it is likely that the CD46 expression levels of primary cell cultures are high enough for infection with EdH-EGFP. We are now examining the expression levels of CD46 in cell lines and primary cell cultures and in tissues of cynomolgus monkeys. Another possible explanation for the limited infection of EdH-EGFP2 in macaque tissues is the inefficient replication of MV due to interferons. Yoshikawa et al. reported that primate kidney cells rapidly lose interferon-inducing activity and permit poliovirus replication when the cells are cultured in vitro (40). MV replication in monkey tissues may be inhibited by interferon, whereas MV replication in primary cell cultures can occur due to the lack of interferon-inducing activity.

Flow cytometric analysis showed that lymphocytes expressing SLAM were infected with both IC323-EGFP2 and EdH-EGFP2 (Fig. 6). It is known that stimulated lymphocytes can be efficiently infected with MV and that SLAM is highly expressed in stimulated lymphocytes (11). Thus, the activation status of lymphocytes may be important for infection with MV, and infection of unstimulated lymphocytes with EdH-EGFP2 by the CD46-mediated pathway would not result in efficient MV replication. As a result, lymphocytes expressing SLAM may appear to be equally infected with both strains. Recently, two groups revealed that both SLAM and CD46 are required for stable transduction of resting human lymphocytes with lentiviral vectors pseudotyped with the vaccine MV F and H proteins (8, 42). Thus, another possibility is that SLAM binding in addition to CD46 binding may be required for efficient infection of lymphocytes with EdH-EGFP2. SLAM binding and subsequent signaling (8, 42) may be important for efficient MV infection.

A previous study in which monkeys were infected with pathogenic and Edmonston vaccine strains via an aerosol route showed that only the pathogenic strain caused massive infection in lymphoid tissues (5). We also infected monkeys with IC323-EGFP2 and EdH-EGFP2 via the aerosol route, and we found that both strains caused massive infection in lymphoid tissues (Fig. 3). This result indicated that the Edmonston H protein does not influence the extent of infection in lymphoid tissues. Proteins other than the H protein, possibly viral polymerase proteins (30), may regulate MV replication in lymphoid tissues.

Suppression of the production of IL-12 during measles was proposed (10). We found that the initial level of IL-12 was high for 3 monkeys (no. 5056, 5057, and 5062) but low for 3 other monkeys (no. 5058, 5068, and 5069) (Fig. 7). We do not have an explanation for this difference. However, our results indicated that the IL-12 levels were not significantly induced at early time points during MV infection. This result may be consistent with a previous observation of suppressed serum levels of IL-12 during MV infection in rhesus macaques (13, 26). Interestingly, Th1-type cytokines (IFN-γ and IL-2) were induced in all monkeys irrespective of the IL-12 level. The induction of IFN-γ in plasma at early time points is consistent with that in previous studies of human measles (10, 19, 24, 41). A previous study showed no significant induction of IL-2, IL-12, and IFN-γ in monkeys infected with wild-type MV (4). However, in that experiment the induction of IL-2, IL-12, and IFN-γ was measured by quantitating their mRNAs by real-time RT-PCR using RNA extracted from PBMCs. Real-time RT-PCR data may not coincide with the actual amounts of cytokines in plasma.

In summary, the current study showed that the H protein of the Edmonston vaccine strain alters the cell specificity of wild-type MV in vitro but not the tropism in macaques. SLAM+ cells were main target for both IC323-EGFP2 and EdH-EGFP2 in macaques. In addition, it is suggested that the Edmonston vaccine H protein attenuates MV growth in vivo, especially at a later stage. It has long been proposed that the vaccine H protein attenuates the virus growth in vivo by several mechanisms (e.g., CD46-mediated signaling in infected cells or downregulation of CD46 in infected cells and subsequent complement-mediated cell lysis) (14). It will be interesting to examine the type I interferon production and the downregulation of CD46 in MV-infected cells in monkeys infected with EdH-EGFP2 or MV vaccine strains.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Y. Yanagi and M. Takeda for providing plasmids and cells, B. Moss for vaccinia virus vTF7-3, N. Kimura for primary monkey astroglial cells, A. Harashima, M. Fujino, H. Sato, Y. Saito, A. Wakutsu, K. Kato, and T. Nishie for excellent technical support, and Y. Yasutomi, K. Terao, A. Yamada, T. Sata, H. Hasegawa, and K. Komase for valuable discussions and continuous support. We also thank K. Ho for critical readings and valuable comments.

This work was supported in part by a grant-in-aid (no. 21022006 and 23659227) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 11 January 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Anderson BD, Nakamura T, Russell SJ, Peng K-W. 2004. High CD46 receptor density determines preferential killing of tumor cells by oncolytic measles virus. Cancer Res. 64:4919–4926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Auwaerter PG, et al. 1999. Measles virus infection in rhesus macaques: altered immune responses and comparison of the virulence of six different virus strains. J. Infect. Dis. 180:950–958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. de Swart RL, et al. 2007. Predominant infection of CD150+ lymphocytes and dendritic cells during measles virus infection of macaques. PLoS Pathog. 3:e178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Devaux P, Hodge G, McChesney MB, Cattaneo R. 2008. Attenuation of V- or C-defective measles viruses: infection control by the inflammatory and interferon responses of rhesus monkeys. J. Virol. 82:5359–5367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. de Vries RD, et al. 2010. In vitro tropism of attenuated and pathogenic measles virus expressing green fluorescent protein in macaques. J. Virol. 84:4714–4724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dorig RE, Marcil A, Chopra A, Richardson CD. 1993. The human CD46 molecule is a receptor for measles virus (Edmonston strain). Cell 75:295–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Enders JF, Peebles TC. 1954. Propagation in tissue cultures of cytopathic agents from patients with measles. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 86:277–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Frecha C, et al. 2011. Measles virus glycoprotein-pseudotyped lentiviral vector-mediated gene transfer into quiescent lymphocytes requires binding to both SLAM and CD46 entry receptors. J. Virol. 85:5975–5985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fuerst TR, Niles EG, Studier FW, Moss B. 1986. Eukaryotic transient-expression system based on recombinant vaccinia virus that synthesizes bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 83:8122–8126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Griffin DE, Ward BJ, Jauregui E, Johnson RT, Vaisberg A. 1990. Immune activation during measles: interferon-γ and neopterin in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid in complicated and uncomplicated disease. J. Infect. Dis. 161:449–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Griffin DE. 2007. Measles virus, p 1551–1585 In Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Roizman B, Straus SE. (ed), Fields virology, 5th ed Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hashimoto K, et al. 2002. SLAM (CD150)-independent measles virus entry as revealed by recombinant virus expressing green fluorescent protein. J. Virol. 76:6743–6749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hoffman SJ, et al. 2003. Vaccination of rhesus macaques with a recombinant measles virus expressing interleukin-12 alters humoral and cellular immune responses. J. Infect. Dis. 188:1553–1561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kemper C, Atkinson JP. 2009. Measles virus and CD46. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 329:31–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kobune F, Sakata H, Sugiura A. 1990. Marmoset lymphoblastoid cells as a sensitive host for isolation of measles virus. J. Virol. 64:700–705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kobune F, et al. 1996. Nonhuman primate models of measles. Lab. Anim. Sci. 46:315–320 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lamb RA, Parks GD. 2007. Paramyxoviridae: the viruses and their replication, p 1449–1496 In Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Roizman B, Straus SE. (ed), Fields virology, 5th ed Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 18. Leonard VHJ, et al. 2008. Measles virus blind to its epithelial cell receptor remains virulent in rhesus monkeys but cannot cross the airway epithelium and is not shed. J. Clin. Invest. 118:2448–2458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moss WJ, Ryon JJ, Monze M, Griffin DE. 2002. Differential regulation of interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5, and IL-10 during measles in Zambian children. J. Infect. Dis. 186:879–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Muhlebach MD, et al. 2011. Adherens junction protein nectin-4 is the epithelial receptor for measles virus. Nature 480:530–533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Naniche D, et al. 1993. Human membrane cofactor protein (CD46) acts as a cellular receptor for measles virus. J. Virol. 67:6025–6032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Navaratnarajah C, Leonard KVHJ, Cattaneo R. 2009. Measles virus glycoprotein complex assembly, receptor attachment, and cell entry. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 330:59–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Noyce RS, et al. Tumor cell marker PVRL4 (nectin 4) is an epithelial cell receptor for measles virus. ProS Pahog. 7:e1002240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ohga S, Miyazaki C, Okada K, Akazawa K, Ueda K. 1992. The inflammatory cytokines in measles: correlation between serum interferon-γ levels and lymphocyte subpopulations. Eur. J. Pediatr. 151:492–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Plumet S, Gerlier D. 2005. Optimized SYBR green real-time PCR assay to quantify the absolute copy number of measles virus RNAs using gene specific primers. J. Virol. Methods 128:79–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Polack FP, Hoffman SJ, Moss WJ, Griffin DE. 2002. Altered synthesis of interleukin-12 and type 1 and type 2 cytokines in rhesus macaques during measles and atypical measles. J. Infect. Dis. 185:13–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rota JS, Wang ZD, Rota PA, Bellini WJ. 1994. Comparison of sequences of the H, F, and N coding genes of measles virus vaccine strains. Virus Res. 31:317–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tahara M, Takeda M, Seki F, Hashiguchi T, Yanagi Y. 2007. Multiple amino acid substitutions in hemagglutinin are necessary for wild-type measles virus to acquire the ability to use receptor CD46 efficiently. J. Virol. 81:2564–2572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Takeda M, et al. 2005. Efficient rescue of measles virus from cloned cDNA using SLAM-expressing Chinese hamster ovary cells. Virus Res. 108:161–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Takeda M, et al. 2008. Measles viruses possessing the polymerase protein genes of the Edmonston vaccine strain exhibit attenuated gene expression and growth in cultured cells and SLAM knock-in mice. J. Virol. 82:11979–11984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Takeda M, et al. 2007. A human lung carcinoma cell line supports efficient measles virus growth and syncytium formation via a SLAM- and CD46-independent mechanism. J. Virol. 81:12091–12096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Takeda M, et al. 2000. Recovery of pathogenic measles virus from cloned cDNA. J. Virol. 74:6643–6647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Takeuchi K, Miyajima N, Kobune F, Tashiro M. 2000. Comparative nucleotide sequence analyses of the entire genomes of B95a cell-isolated and Vero cell-isolated measles viruses from the same patient. Virus Genes 20:253–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Takeuchi K, et al. 2005. Stringent requirement for the C protein of wild-type measles virus for growth in vitro and in macaques. J. Virol. 79:7838–7844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Takeuchi K, et al. 2002. Recombinant wild-type and Edmonston strain measles viruses bearing heterologous H proteins: role of H protein in cell fusion and host cell specificity. J. Virol. 76:4891–4900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tatsuo H, Ono N, Tanaka K, Yanagi Y. 2000. SLAM (CDw150) is a cellular receptor for measles virus. Nature 406:893–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. van Binnendijk RS, van der Heijden RW, van Amerongen G, UytdeHaag FG, Osterhaus AD. 1994. Viral replication and development of specific immunity in macaques after infection with different measles virus strains. J. Infect. Dis. 170:443–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. von Messling V, Milosevic D, Cattaneo R. 2004. Tropism illuminated: lymphocyte-based pathways blazed by lethal morbillivirus through the host immune system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:14216–14221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yamanouchi K, et al. 1970. Giant cell formation in lymphoid tissue of monkeys inoculated with various strains of measles virus. Jpn. J. Med. Sci. Biol. 23:131–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yoshikawa T, et al. 2006. Role of the alpha/beta interferon response in the acquisition of susceptibility to poliovirus by kidney cells in culture. J. Virol. 80:4313–4325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yu X, et al. 2008. Measles virus infection in adults induces production of IL-10 and is associated with increased CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 181:7356–7366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhou Q, Schneider IC, Gallet M, Kneissl S, Buchholz CJ. 2011. Resting lymphocyte transduction with measles virus glycoprotein pseudotyped lentiviral vectors relies on CD46 and SLAM. Virology 413:149–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]