Abstract

The incorporation of viral envelope (Env) glycoproteins into nascent particles is an essential step in the production of infectious human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1). This process has been shown to require interactions between Env and the matrix (MA) domain of the Gag polyprotein. Previous studies indicate that several residues in the N-terminal region of MA are required for Env incorporation. However, the precise mechanism by which Env proteins are acquired during virus assembly has yet to be fully defined. Here, we examine whether a highly conserved glutamate at position 99 in the C-terminal helix is required for MA function and HIV-1 replication. We analyze a panel of mutant viruses that contain different amino acid substitutions at this position using viral infectivity studies, virus-cell fusion assays, and immunoblotting. We find that E99V mutant viruses are defective for fusion with cell membranes and thus are noninfectious. We show that E99V mutant particles of HIV-1 strains LAI and NL4.3 lack wild-type levels of Env proteins. We identify a compensatory substitution in MA residue 84 and show that it can reverse the E99V-associated defects. Taken together, these results indicate that the C-terminal hydrophobic pocket of MA, which encompasses both residues 84 and 99, has a previously unsuspected and key role in HIV-1 Env incorporation.

INTRODUCTION

The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) matrix (MA) protein has been implicated in both early and late stages of the viral replication cycle (2, 17). Early events are those that occur between the docking of a mature virus particle on the receptor of a target cell and the integration of proviral DNA into cellular DNA. Within the mature virion, the majority of MA molecules are located along the inner leaflet of the viral membrane (23, 44). However, a small subset of MA molecules is selectively phosphorylated and retained inside the viral core (6, 22, 37, 60, 66). Although controversial, it has been suggested that these MA molecules may assist in early events such as uncoating, reverse transcription, or nuclear import of the preintegration complex (PIC) (5, 8, 19, 24, 28, 29, 54, 55, 64, 70). Following import of the PIC into the nucleus, the viral DNA integrates into the DNA of the host cell.

Late events begin with expression of the viral genes and culminate with the release and maturation of progeny virus. During this phase, MA exists as the N-terminal domain of the HIV-1 Pr55Gag polyprotein (Gag). In this form, MA functions in virus assembly by targeting Gag molecules to the plasma membrane (PM) and facilitating incorporation of the envelope (Env) glycoproteins into nascent particles (2, 4, 10, 15, 32, 45, 46, 56, 71). Once immature virus buds from the cell surface, the viral protease cleaves the Gag polyproteins, separating the mature 17-kDa MA (132 amino acids) from the other structural proteins (16, 24). During this maturation step, a protein rearrangement of the viral core occurs, generating the conical structure characteristic of infectious HIV-1 virions. In the context of immature particles, it is thought that the MA domain delays proteolytic cleavage until the particle is fully budded from the PM, thereby preventing emerging virus from reinfecting the producer cell (41, 69).

Both nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and X-ray crystallographic studies have determined that MA contains five α helices: four that form a globular head and one at the C terminus which projects away from the others (26, 36). In addition to structural analyses, molecular genetic approaches have been used to identify several functional domains within the protein. A highly basic region spanning residues 17 through 33 forms a positively charged surface thought to interact with negatively charged phospholipids on the inner face of the PM (18, 19, 45, 46, 48, 59). In concert with a myristic acid moiety at the N terminus, this domain is important for Gag targeting to the PM during virus assembly (26, 36, 58, 62, 73). It has also been reported that at least two domains within MA are involved in particle production. Alterations in residues 56 through 60 reduce virus production by shortening the half-life of cell-associated Gag proteins (19). Additionally, single amino acid substitutions at MA residues 85 through 89 have been associated with the redirection of particle assembly from the PM to sites within cytoplasmic vesicles (19).

Previous studies have shown that MA is required for efficient incorporation of Env into virus particles (32). However, the precise mechanism involved in this assembly step has yet to be fully defined. Single amino acid substitutions within the N terminus of MA, specifically, G11R, L13E, W16A, L30E, V34E, or A37P, have been shown to abrogate Env incorporation into particles (20, 21, 31, 42, 47, 49, 68, 70). However, functional analyses of viruses with in-frame deletions in MA suggest that Env incorporation might involve other regions of the protein (3, 11). For example, deletion of MA residues 27 through 30, 63 through 65, 77 through 80, or 98 through 100 has been shown to result in the production of Env-deficient particles (13).

A PCR-based mutagenesis strategy was previously used to generate HIV proviral clones that could be used for a systematic mutational analysis of MA function (14). Subsequently, a proviral clone containing a glutamate-to-valine substitution at residue 99 was generated for additional studies. Residue 99 is located at the beginning of the MA C-terminal helix, a region that spans amino acids 96 through 121 (26). Sequence alignment of >1,100 HIV-1 group M MA proteins in the Los Alamos HIV database reveals a remarkably high degree of conservation at this position. In fact, of the MA sequences analyzed, residue 99 is almost exclusively a glutamate (99%), with aspartate being an alternative (1%) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Surprisingly, whether a glutamate at position 99 is required for MA function or HIV-1 replication has not been previously examined. Nonetheless, several studies have described the effects of other mutations at the beginning of the MA C-terminal helix. For example, a K98E substitution in MA has been reported to cause an early postentry defect in virus infectivity (29). Also, an HIV proviral clone with an A100E substitution in MA failed to produce viral particles following transfection into CEM (12D-7) cells (19). Lastly, deletion of MA residues 98 through 100 has been shown to disrupt Env incorporation into virus particles (13).

Here, we examine the role of glutamate 99 in MA function and HIV-1 replication. We analyze a panel of mutant viruses that contain different amino acid substitutions at this position using virus infectivity studies, virus-cell fusion assays, and immunoblotting.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissue culture cell lines.

HeLa, 293-T, or TZM-bl cells were grown in 1× Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Pen-Strep). TZM-bl cells are derived from a HeLa clone and express relatively high surface levels of CD4, CCR5, and CXCR4 (61). They contain stably integrated reporter genes that encode the Escherichia coli β-galactosidase (β-Gal) and Renilla firefly luciferase. This reporter cell line is susceptible to infection by both R5 and X4 HIV-1 isolates (65). MT-4, M8166, and C8166 cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS and 1% Pen-Strep. All cell lines were grown at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

DNA constructions.

HIV-1 mutations were created by the QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) as previously described (72), using the pLAI or pNL4.3 proviral clone (1, 30, 51). These proviral clones were obtained from the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program of NIAID, NIH. The sequences of the mutagenic primers are written in the 5′ to 3′ direction: L13E/f, GTA TTA AGC GGG GGA GAA GAA GAT CGA TGG GAA AAA ATT C; L13E/r, G AAT TTT TTC CCA TCG ATC TTC TTC TCC CCC GCT TAA TAC; L21K/f, GA TGG GAA AAA ATT CGG AAA AGG CCA GGG GGA AAG; L21K/r, CTT TCC CCC TGG CCT TTT CCG AAT TTT TTC CCA TC; K32E/f, G AAA AAA TAT AAA TTA GAA CAT ATA GTA TGG GCA AGC; K32E/r, GCT TGC CCA TAC TAT ATG TTC TAA TTT ATA TTT TTT C; LAI-T84V/f, C ATT ATA TAA TAC AGT AGC AGT CCT CTA TTG TGT GCA TC; LAI-T84V/r, GA TGC ACA CAA TAG AGG ACT GCT ACT GTA TTA TAT AAT G; LAI-E99V/f, G ATA AAA GAC ACC AAG GTA GCT TTA GAC AAG ATA G; LAI-E99V/r, C TAT CTT GTC TAA AGC TAC CTT GGT GTC TTT TAT C; E99A/f, G ATA AAA GAC ACC AAG GCA GCT TTA GAC AAG ATA G; E99A/r, C TAT CTT GTC TAA AGC TGC CTT GGT GTC TTT TAT C; E99D/f, G ATA AAA GAC ACC AAG GAC GCT TTA GAC AAG ATA G; E99D/r, C TAT CTT GTC TAA AGC GTC CTT GGT GTC TTT TAT C; E99G/f, G ATA AAA GAC ACC AAG GGA GCT TTA GAC AAG ATA G; E99G/r, C TAT CTT GTC TAA AGC TCC CTT GGT GTC TTT TAT C; E99K/f, G ATA AAA GAC ACC AAG AAA GCT TTA GAC AAG ATA G; E99K/r, C TAT CTT GTC TAA AGC TTT CTT GGT GTC TTT TAT C; NL-V84T/f, CAT TAT ATA ATA CAA TAG CAA CCC TCT ATT GTG TGC ATC; NL-V84T/r, GAT GCA CAC AAT AGA GGG TTG CTA TTG TAT TAT ATA AT; NL-E99V/f, GTA AAA GAC ACC AAG GTA GCC TTA GAT AAG ATA G; NL-E99V/r, C TAT CTT ATC TAA GGC TAC CTT GGT GTC TTT TAC; LAIdelGAG/f, G AGA GCG TCA GTA TAA AGC GGG TGA GAA TTA GAT CGA TG; LAIdelGAG/r, CA TCG ATC TAA TTC TCA CCC GCT TTA TAC TGA CGC TCT C; Env144/f, GGA TAT TGA TGA TTA TCG TTT CAG ACC CAC; and Env144/r, CGA TAA TCA TCA ATA TCC CTG CCT AAC TCT.

Sanger sequencing of both DNA strands confirmed nucleotide changes in the HIV-1 mutant proviral clones. All mutations created in the MA domain are named on the basis of their proximity to the initial methionine in the Gag coding sequence. The proviral clone pLAI-Gag (−) encodes a nonfunctional gag gene and was created by introducing two stop codons proximal to the start of the gag reading frame, as previously described (34, 35). Truncations of the HIV-1 gp41 cytoplasmic tail (CT) were made by introducing two consecutive stop codons into the gp41 coding sequences, as described previously (34, 35). The gp41 proteins generated from transfection of the LAI-Δ144 proviral clones contain an abbreviated CT that is 6 residues instead of the normal 150 amino acids in length. The pLAI-ΔEnv proviral clone encodes a nonfunctional env gene, due to removal of the 582-nucleotide BglII/BglII fragment (bases 6638 to 7220) located early in the env coding sequence. The pBLaM-Vpr plasmid expresses β-lactamase (BLaM) fused to the amino terminus of Vpr under the control of the cytomegalovirus promoter (9).

Virus production.

Wild-type (WT) and mutant virus stocks were produced by transient transfection of proviral clones into 293T cells using TransIT-LTI transfection reagent (Mirus Corp.). Viruses were harvested after 48 h and clarified through a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter. Stocks were normalized for reverse transcriptase (RT) activity using the enzymatic assay described below, and aliquots were subsequently stored at −80°C. HIV-1 particles carrying β-lactamase proteins were produced by cotransfection of an individual proviral clone and pBLaM-Vpr at a ratio of 3:1. For immunoblot analysis, HeLa cells were transiently transfected with the individual proviral clones and viral lysates prepared as previously described (34).

RT activity assays.

HIV-1 RT activity was measured as previously described (52). For each sample, 5 μl of filtered culture supernatant was mixed with 10 μl solution A (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.9, 300 mM KCl, 10 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 0.1% NP-40) and incubated for 15 min at 37°C. Viral lysates were then combined with 25 μl solution B [50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.9, 150 mM KCl, 5 mM DTT, 15 mM MgCl2, 0.05% NP-40, 10 μg/ml poly(A), 0.250 U/ml oligonucleotide dTTP, 10 μCi/ml [3H]TTP], and incubated overnight at 37°C. Reaction products were precipitated using stop solution (100% trichloroacetic acid, 0.5 M Na4P2O7 · 10H2O), and RT activity was determined as previously described (72).

Immunoblot analyses.

Cell or viral lysates were resolved on 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to Hybond-C Extra nitrocellulose (NC) membranes (Amersham Biosciences) using a semidry blotter. NC membranes were blocked with 5% dry milk in 1× TBST buffer (25 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, pH 7.4, and 0.1% Tween 20) at room temperature for 1 h and then incubated with primary monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) directed against HIV-1 Env (Chessie-8, diluted 1:250), HIV-1 Gag (183-H12-5C, diluted 1:500; NIH AIDS Reagent Program), or human β-actin (diluted 1:4,400; Sigma). Following three 10-min washes in 1× TBST buffer, membranes were incubated with goat anti-mouse or mouse anti-rabbit secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (diluted 1:10,000; Sigma). Bands were detected and visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (SuperSignal West Pico; Thermo Scientific) with Kodak X-Omat Blue film.

Virus-cell fusion assays.

TZM-bl cells, seeded at 10 × 104 cells per well, were inoculated with virus using spinoculation (2,100 × g) at room temperature for 30 min in a total volume of 50 μl. Cells were incubated for up to 3 h at 37°C. The BLaM substrate CCF2-AM dye (20 μM; LiveBLAzer FRET-B/G loading kit; Invitrogen) was prepared according to the manufacturer's standard substrate loading protocol, with the exception that solution C was diluted 1:6 in 1× HBSS++ (Hanks' balanced salt solution, 20 μM HEPES, 2 mM glutamine). The CCF2-AM solution was added to cells, and the cultures were incubated overnight in the dark at room temperature. Cells were washed in cold 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and fluorescence emission was measured at 447 nm or 520 nm following excitation at 409 nm using a fluorometer (BioTek Synergy 2). Intracellular BLaM activity was measured and normalized as previously described (38).

Beta-Glo assays of viral infectivity.

The Beta-Glo assay system provides a highly sensitive, quantitative analysis of viral infectivity with a wide range of HIV-1 isolates (25). In living cells, this substrate is cleaved by β-galactosidase to galactose and luciferin, the latter being used by firefly luciferase to generate a luminescent signal that is proportional to the amount of β-galactosidase. Following HIV-1 infection, the enzymatic activity of luciferase in TZM-bl cells can be quantified in terms of relative luciferase units (RLUs). The RLU values obtained are directly proportional to the number of infectious virus particles in the viral inoculum. TZM-bl cells were seeded at 10 × 104 cells per well of a 96-well plate. Duplicate wells were infected with equal amounts of virus, and plates were incubated for 24 or 48 h at 37°C. Cells were lysed at room temperature by the addition of Beta-Glo substrate (Promega). Luciferase activity was quantified using a luminometer and normalized as previously described (25).

RESULTS

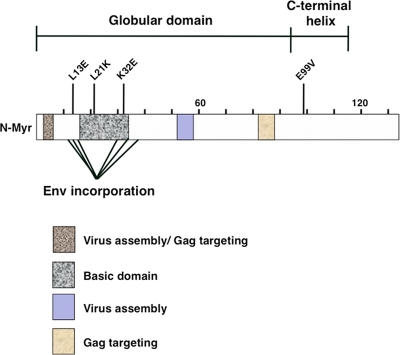

To identify residues involved in a specific MA function, several groups have analyzed single amino acid substitutions at highly conserved positions within the protein. For example, an L13E substitution is one of six MA mutations that abrogates incorporation of full-length HIV-1 Env into virus particles during assembly (20). An L21K substitution in the basic domain of MA enhances membrane binding of Gag and accelerates Gag processing, resulting in a postentry defect in virus particles (29). Finally, a K32E substitution in MA abolishes viral infectivity in Jurkat cells without significantly affecting virus assembly and release or Env incorporation (31). Figure 1 shows a schematic representation of the new E99V substitution relative to MA functional domains and previously characterized MA single amino acid substitutions.

Fig 1.

Functional domains and single amino acid substitutions in the HIV-1 MA protein. A schematic representation of previously defined functional domains in HIV-1 MA and the relative locations of previously characterized single amino acid substitutions. The E99V MA substitution analyzed in this study is located at the beginning of the C-terminal helix of the protein.

E99V MA-containing particles can assemble but are defective in a single-cycle infection.

To determine whether the LAI proviral clone containing the E99V MA substitution (pLAI-E99V) could produce viral particles, 293T cells were transiently transfected with either a WT proviral clone (pLAI-WT) or pLAI-E99V, using cationic liposomes. After 48 h, cell supernatants were collected and levels of virus particle production were determined using an enzymatic assay for RT activity and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for HIV-1 p24. Results from these assays indicate that production of LAI-E99V particles was comparable to that of LAI-WT (data not shown).

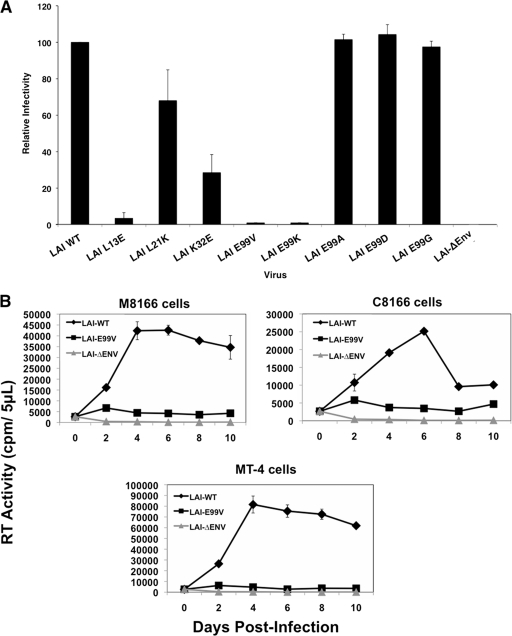

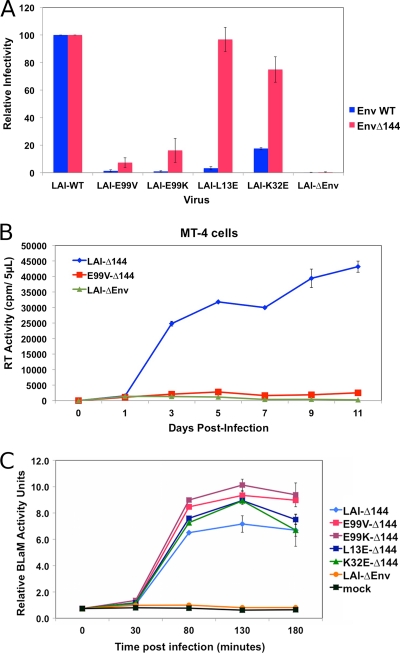

To test whether different MA substitutions affect viral infectivity, 293T cells were transfected with pLAI-WT, an LAI proviral clone encoding either the L13E, L21K, K32E, or E99V MA substitution (pLAI-L13E, pLAI-L21K, pLAI-K32E, and pLAI-E99V, respectively), or an LAI proviral clone with a nonfunctional env gene (pLAI-ΔEnv). Virus in each culture supernatant was normalized on the basis of RT activity, and equal units were added to TZM-bl cells cultured in 96-well plates. After 24 h, Beta-Glo substrate was added to the cells and luciferase activity in each well was quantified in relative luciferase units (RLUs) using a luminometer. The RLU value from each infection was normalized using the LAI-WT value, which represents 100% infectivity. Figure 2A shows that LAI-WT, but not LAI-ΔEnv, was highly competent for viral infection in this assay. Similar to previous reports, we found that the L13E, L21K, and K32E substitutions in MA reduce viral infectivity by approximately 28.6-fold, 1.5-fold, and 3.5-fold, respectively. Most striking, we observed a 100-fold reduction in infectivity in cells incubated with LAI-E99V. These data suggest that LAI-E99V particles are defective at an early step in the virus life cycle.

Fig 2.

E99V or E99K MA mutant particles have marked defects in virus infectivity and replication. (A) Virus stocks generated in 293T cells by transfection with the indicated pLAI molecular clones were normalized on the basis of RT activity and used to infect TZM-bl cells. Single-cycle infectivity was determined at 24 h postinfection using the Beta-Glo infectivity assay and a luminometer. Infectivity is based on the level of LAI-WT, which represents 100% infectivity. The data shown are representative of four independent experiments performed in duplicate. (B) Virus stocks generated in 293T cells by transfection with the indicated pLAI clones were normalized on the basis of RT activity and used to infect various human T-cell lines: M8166 (top left), C8166 (top right), or MT-4 cells (bottom). Fresh cells and medium were added to each culture on day 7. RT activities in cell culture supernatants were monitored every other day using a standard enzymatic assay. The data shown are representative of two independent experiments performed in duplicate.

Because LAI-E99V was markedly less infectious than the other viruses tested, we analyzed the functional significance of glutamate at residue 99 using specific amino acid substitutions at this position in MA. We selected an alanine or a glycine substitution because of their neutral side chain groups compared to glutamate (E99A, E99G). An aspartate substitution was chosen on the basis of its charge similarity and slightly larger mass (E99D). Lastly, a lysine substitution was selected because it places a negative rather than a positive charge at this position (E99K). LAI proviral clones encoding these single amino acid substitutions at residue 99 were generated using PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis and individually transfected into 293T cells to produce virus. The levels of viral infectivity were monitored in TZM-bl cells as described in the previous section. Our results indicate that exchanging glutamate for an alanine, glycine, or aspartate at residue 99 of MA had no discernible effect on viral infectivity (Fig. 2A). In contrast, a lysine substitution at this position led to a 100-fold decrease in viral infectivity, a level comparable to that observed for the E99V substitution.

We did not detect virus infection in cells inoculated with LAI-E99V using single-cycle reporter assays. However, it is possible that infection was occurring at a level below the detection limit of this assay. Alternatively, the observed infectivity defect might be an anomaly of TZM-bl cells. As a complementary approach for determining viral infectivity, we examined whether LAI-E99V retained the ability to initiate a spreading infection in different human T-cell lines. MT-4, M8166, or C8166 cells were inoculated with LAI-WT, LAI-E99V, or LAI-ΔEnv. At 4 h postinfection, cells were washed and replated in fresh medium and incubated further for 10 days. An aliquot of each culture supernatant was obtained every other day and stored at −20°C. On day 7, one-half of the culture volume was replaced with an equal volume of fresh cell-medium suspension (1:1 ratio). The level of RT activity in each aliquot was measured using a standard enzymatic assay. Figure 2B shows the results from viral infectivity studies conducted with these viruses. Robust levels of viral replication were detected in cultures incubated with LAI-WT but not those incubated with LAI-ΔEnv. Consistent with the data from single-cycle infectivity assays, LAI-E99V was unable to replicate in any of these T-cell lines. Taken together, our results indicate that LAI-E99V has a marked defect in viral infectivity.

Certain amino acid substitutions in MA have previously been shown to affect the efficiency of Gag processing (23, 27, 29). To determine whether Gag processing is affected in LAI-E99V particles, WT or mutant viruses were produced in 293T cells and harvested from culture supernatants using centrifugation. Viral lysates were resolved on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel and analyzed by immunoblotting using an anti-HIV-1 p24 MAb. We found that the level of Gag processing was comparable between the LAI-WT and LAI-E99V viruses (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

E99V and E99K substitutions in MA disrupt Env incorporation into virus particles.

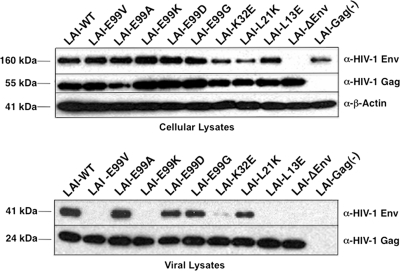

Because certain amino acid substitutions in MA have been shown to disrupt Env incorporation in nascent particles (19, 20, 21, 31, 47), we examined whether this process might be impaired in viruses lacking a glutamate at position 99 in MA. HeLa cells were transfected with the proviral clones shown in Fig. 2A (pLAI-WT, pLAI-E99V, pLAI-E99A, pLAI-E99K, pLAI-E99D, pLAI-E99G, pLAI-K32E, pLAI-L21K, pLAI-L13E, and pLAI-ΔEnv) or an LAI proviral clone with two stop codons proximal to the start of the gag reading frame [pLAI-Gag (−)]. After 48 h, transfected cells were harvested and culture supernatants were normalized on the basis of RT activity as described above. Cellular and viral lysates were prepared and analyzed for Env expression and particle incorporation, respectively, using immunoblotting with an anti-HIV-1 Env MAb as previously described (13).

Data shown in Fig. 3 (top) indicate that Env precursor proteins were expressed in all cultures transfected with a proviral clone containing an intact env open reading frame. Consistent with previous findings, Env precursor proteins were expressed in cultured cells transfected with pLAI-Gag (−) but not in those transfected with pLAI-ΔEnv (34).

Fig 3.

HIV-1 Env proteins are inefficiently incorporated into E99V or E99K MA mutant particles. Transfected HeLa cells (top) or virus particles (bottom) were harvested, and cellular or viral lysates were prepared as previously described (13). The levels of Env proteins in lysates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting using monoclonal antibodies directed against HIV-1 Env, HIV-1 Gag, and human β-actin or against HIV-1 Env and HIV-1 Gag, respectively.

Figure 3 (bottom) also shows results from immunoblot analysis of Env proteins of the corresponding viral lysates. As previously reported, LAI-L13E was found to be completely devoid of Env proteins, a result consistent with a defect in Env incorporation (20). Similar to a previous study, the level of Env incorporated into L21K particles was comparable to that of LAI-WT (29). However, we observed a marked reduction in the amount of Env in LAI-K32E particles (31). The absence of Env in the pLAI-Gag (−) culture confirms that the signals detected represent virus-associated Env and not viral glycoproteins trapped in intracellular vesicles.

We found that the amounts of Env in LAI-E99A, LAI-E99D, and LAI-E99G particles were comparable to those in LAI-WT particles. Most importantly, we determined that the LAI-E99V and LAI-E99K particles were devoid of viral glycoproteins. Given that cells transfected with pLAI-E99V or pLAI-E99K expressed wild-type levels of Env (Fig. 3, top), the E99V and E99K MA substitutions appear to disrupt incorporation of Env into nascent particles.

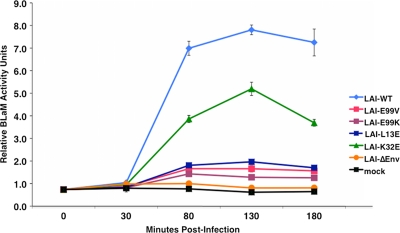

E99V and E99K MA-containing particles are defective in membrane fusion.

Results from our immunoblot analyses are consistent with LAI-E99V and LAI-E99K particles having a major defect in Env incorporation. Nonetheless, we considered the possibility that Env glycoproteins were incorporated into particles at levels below the detection limits of the assay and, thus, could potentially facilitate membrane-virus fusion events. In fact, a previous study demonstrated that a marked reduction in Env incorporation does not always correlate with a proportional defect in membrane fusion capacity (11, 43). Thus, we examined whether these particles are also defective in their ability to fuse with target-cell membranes.

We used a recently modified fusion assay that measures BLaM activity as an indicator of virus-cell fusion events in living TZM-bl cells postfusion with virus containing chimeric BLaM-Vpr proteins (9, 38). In parallel, we monitored single-cycle infectivity of WT or mutant viruses using the Beta-Glo assay, as described for Fig. 2A, and our results agreed with our previous infectivity data (data not shown). Representative data from virus-cell fusion assays using LAI-E99V, LAI-E99K, LAI-L13E, and LAI-K32E are shown in Fig. 4. At 80 min and later times, we observed high levels of BLaM activity in cells incubated with LAI-WT. In contrast, minimal BLaM activity was detected in mock- or LAI-ΔEnv-treated cells, even at late times (180 min).

Fig 4.

E99V or E99K MA mutant particles have a marked defect in membrane fusion. Equal amounts of virus were added to TZM-bl cells grown in 96-well plates. The plates were centrifuged at room temperature for 30 min and then incubated further at 37°C for 50, 100, or 150 min. Cells were washed with 1× PBS at the indicated times, and the BLaM substrate was added to the culture medium. Plates were incubated overnight at room temperature to allow cleavage of the loaded substrate. Cellular BLaM activity was monitored as an indicator of virus-cell fusion events using a fluorimeter.

In these studies, we observed a direct correlation between the fusion capacity of each virus and its level of infectivity. Notably, few discernible fusion events were detectable at each sampling time for cells incubated with LAI-E99V, LAI-E99K, or LAI-L13E particles, each of which is devoid of Env proteins. These results suggest that, similar to LAI-L13E, the LAI-E99V and LAI-E99K particles are defective in membrane fusion and infectivity due to a disruption in Env incorporation.

An E99V MA-associated defect is mitigated in another HIV-1 strain.

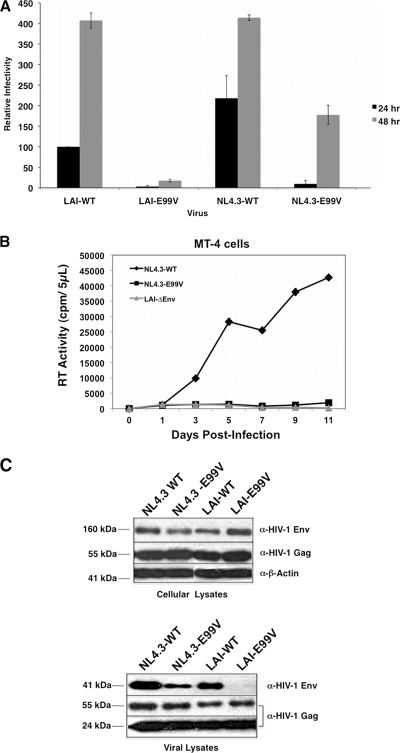

Our results indicate that LAI-E99V particles have pronounced defects in Env incorporation, membrane fusion, and infectivity. Next, we examined whether the E99V MA substitution affects the same processes in a different strain of HIV. We introduced this amino acid substitution into an NL4.3 proviral clone (pNL4.3-E99V) and then virus particles were generated by transient transfection in 293T cells. Single-cycle infectivities for LAI-WT, LAI-E99V, NL4.3-WT, NL4.3-E99V, and LAI-ΔEnv were monitored using the Beta-Glo assay as described for Fig. 2A. In the LAI-E99V infection, we observed a major defect in infectivity, specifically, 32- and 22-fold reductions at the 24- and 48-hour time points, respectively. In contrast, the infectivity defect observed in the NL4.3-E99V infection was less striking: 23-fold and 2.3-fold reductions relative to NL4.3-WT at the same respective time points (Fig. 5A). Replication of LAI-ΔEnv was not detected, confirming the specificity of the assay (data not shown). Thus, the infectivity defect associated with the E99V MA substitution appears to be partially mitigated in NL4.3-derived particles.

Fig 5.

The E99V MA-associated defect is mitigated in NL4.3-derived virus particles. (A) Relative infectivity of each mutant virus and the corresponding wild-type virus was assayed at 24 or 48 h postinfection as described in the legend to Fig. 2A. The assessment of infectivity is based on the level of LAI-WT determined at 24 h postinfection. The data are representative of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. (B) Equal RT units of the indicated viruses were used to infect MT-4 cells, and virus replication kinetics were monitored every other day for 11 days, as described in the legend to Fig. 2B. Fresh cells and medium were added to each culture on day 7. The data shown are representative of two independent experiments performed in duplicate. (C) Lysates of transfected HeLa cells (top) or virus particles (bottom) were prepared and analyzed as described in the legend to Fig. 3.

We also tested whether NL4.3-E99V particles retain the ability to initiate a spreading infection in a human T-cell line. MT-4 cells were inoculated with NL4.3-WT, NL4.3-E99V, or LAI-ΔEnv, and the level of RT activity in each aliquot was measured using a standard enzymatic assay, as described above. Consistent with the results obtained with LAI-E99V, NL4.3-E99V was unable to replicate in MT-4 cells (Fig. 5B).

Next, we examined whether the observed effect on infectivity with NL4.3-derived particles containing an E99V MA substitution was concomitant with an effect on Env incorporation. HeLa cells were transfected with pNL4.3-WT, pNL4.3-E99V, pLAI-WT, or pLAI-E99V. At 48 h, virus in culture supernatants and the cells were harvested and analyzed for Env incorporation and Env expression levels, respectively, as described for Fig. 3. Figure 5C (top) shows that Env precursor proteins were expressed at comparable levels in the transfected cell cultures. Immunoblot analyses of the corresponding viral lysates indicate that NL4.3-E99V particles, but not LAI-E99V particles, contain detectable amount of Env proteins (Fig. 5C, bottom). We consistently found that the level of Env incorporation was reduced in NL4.3-E99V particles compared to that in NL4.3-WT; however, it was substantially higher than that in LAI-E99V particles.

Residue 84 of MA mediates the differential effects of an E99V substitution in HIV-1 LAI and NL4.3 particles.

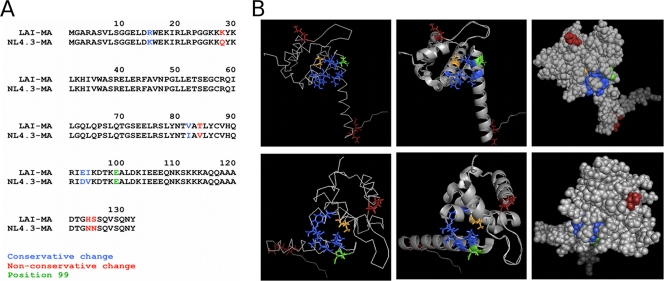

We considered whether the observed differences in infectivity and Env incorporation between LAI-E99V and NL4.3-E99V might be due to amino acid dissimilarity in their MA proteins. We aligned the amino acid sequences of the LAI and NL4.3 MA proteins and found nonconservative changes in four positions: 28, 84, 124, and 125 (Fig. 6A). Using the PyMOL program, we located these residues on a published three-dimensional structure of HIV-1 MA (Protein Data Bank [PDB] accession number 1UPH [63]) and examined their positions relative to residue E99 (Fig. 6B) (12). Our studies revealed that of these four amino acids, residue 84, a threonine in LAI and a valine in NL4.3, has close proximity to glutamate 99, as well as to a C-terminal hydrophobic pocket described previously (7). To examine whether the amino acid difference at position 84 might affect the extent of the defect associated with the E99V substitution in these two strains of HIV-1, we introduced a T84V change into pLAI-WT and pLAI-E99V or the reciprocal substitution, V84T, into pNL4.3-WT and pNL4.3-E99V using PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis. Each mutant proviral clone, pLAI-WT, or pNL4.3-WT was individually transfected into 293T or HeLa cells. At 48 h, virus in culture supernatants was harvested and assayed for single-cycle infectivity, membrane fusion, and Env incorporation as in previous experiments.

Fig 6.

(A) Amino acid differences between the LAI and NL4.3 MA proteins. Alignment of the LAI and NL4.3 MA protein sequences showing four nonconservative amino acid differences (highlighted in red). (B) Relative locations of various residues in the HIV-1 MA structure. Different views of the HIV-1 MA protein (PDB accession number 1UPH [63]) are shown: the top row shows the membrane-binding surface on top, and the bottom row shows MA structures with the membrane-binding surface on the right. Three different depictions of each view are shown: left, stick models; middle, ribbon models; right, space-filling models. Residue E99 is shown in green. The C-terminal hydrophobic pocket consists of V84 (orange), Y86, I92, V94, A100, and K103 (blue) (7). Amino acids 28, 124, and 125 are shown in red; these positions and residue 84 differ between the LAI and NL4.3 MA sequences. Residue 84, a threonine in LAI and a valine in NL4.3, has close proximity to residue 99 compared to the positions of the other three nonconservative changes.

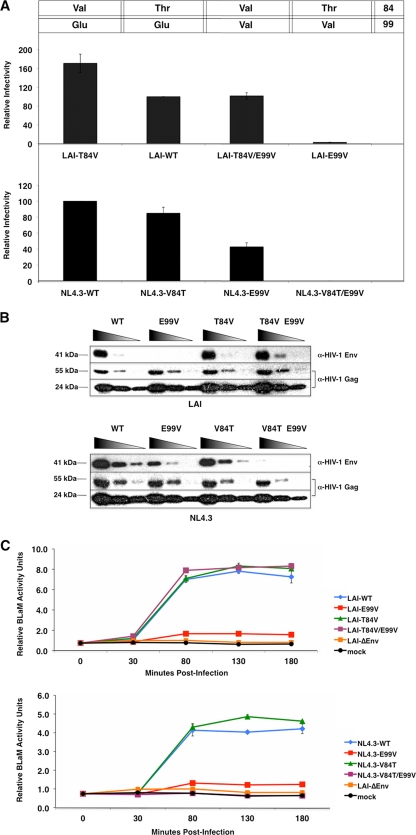

Figure 7A shows results from Beta-Glo infectivity assays in TZM-bl cells using the indicated viruses. A threonine-to-valine change at position 84 in LAI-WT MA resulted in particles that were slightly more infectious than those with the wild-type proteins. The level of infectivity for NL4.3-derived particles with threonine at position 84 in MA was somewhat lower than that of NL4.3-WT. These data suggest that valine, rather than threonine, at position 84 of MA might be more conducive for virus infectivity. Examination of viruses with changes at both positions 84 and 99 in MA revealed that inclusion of the V84T substitution in NL4.3-E99V particles completely abrogated viral infectivity in our assays. Strikingly, inclusion of the MA T84V substitution in LAI-E99V particles restored infectivity to wild-type levels. These data strongly suggest that a valine at position 84 in MA is sufficient to rescue the infectivity defect associated with the E99V MA substitution in both of these HIV-1 strains.

Fig 7.

Amino acid substitution at residue 84 rescues the E99V-associated defect in LAI-derived particles but exacerbates its effect in NL4.3-derived particles. (A) Single-cycle infectivity was monitored at 48 h postinfection using the Beta-Glo infectivity assay, as described in the legend to Fig. 2A. The assessment of infectivity for each mutant virus is based on the level for LAI-WT (top) or NL4.3-WT (bottom), which represents 100% infectivity. The amino acid identities at positions 84 and 99 in each virus are indicated above the graphs. The data shown are representative of two independent experiments performed in duplicate. (B) Viral lysates were prepared and analyzed as described in the legend to Fig. 3. (C) Virus-cell membrane fusion events were assayed in TZM-bl cells as described in the legend to Fig. 4. The data shown are representative of three independent experiments performed in duplicate.

Results of immunoblot analyses of the corresponding viral lysates using an anti-Env MAb are shown in Fig. 7B. No discernible level of disruption in Env incorporation was detected for the LAI- or NL4.3-derived viruses with a single amino acid substitution at MA residue 84. In contrast, NL4.3-V84T/E99V particles were nearly devoid of Env proteins. Consistent with our infectivity data, Env incorporation into LAI-T84V/E99V particles was indistinguishable from that into LAI-WT. Env precursor proteins were expressed at comparable levels in the corresponding transfected HeLa cell lysates (data not shown).

We also examined whether substitution of residue 84 can affect virus-membrane fusion events in the context of the E99V substitution (Fig. 7C). We found that an amino acid substitution in residue 84 of MA in LAI- or NL4.3-derived viruses had no discernible effect on their ability to fuse with cell membranes. Similar to the LAI-E99V and NL4.3-E99V assay results, BLaM activity was deficient in cells incubated with NL4.3-V84T/E99V particles. Most important, cells treated with LAI-T84V/E99V particles contained levels of BLaM activity equal to those produced with LAI-WT. Thus, a valine at residue 84 in MA is sufficient to restore membrane fusion capability to LAI- or NL4.3-derived particles with an E99V substitution.

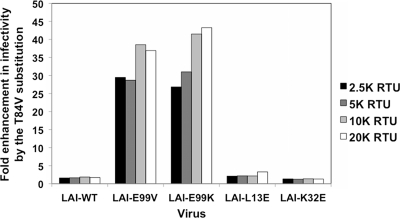

T84V can specifically improve infectivity defects associated with substitutions at E99, but not L13E or K32E MA substitutions.

Based on the data shown in Fig. 7, we posited that valine, rather than threonine, at position 84 of MA is more favorable for virus infectivity in the context of both LAI and NL4.3 strains. However, the observed enhancement in infectivity for an otherwise wild-type MA protein was less substantial than that observed in the context of an E99V substitution. We tested, therefore, whether the rescue conferred by the T84V substitution was specific for changes at residue 99. To determine the specificity of rescue, we tested whether the T84V substitution in LAI could rescue the defects observed with viruses containing an E99K, L13E, or K32E MA substitution. Using PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis, a T84V MA substitution was introduced into pLAI-E99K, pLAI-K32E, and pLAI-L13E to generate pLAI-T84V/E99K, pLAI-T84V/K32E, and pLAI-T84V/L13E proviral clones, respectively. Each LAI-based clone encoding the double amino acid substitutions was individually transfected into 293T, in parallel with its counterpart that contained a single amino acid substitution in MA. At 48 h posttransfection, virus in the culture supernatants was harvested and normalized for subsequent analysis as in previous experiments.

To compare the infectivity levels of LAI-derived viruses with and without the T84V MA substitution, single-cycle infectivity was monitored in TZM-bl cells 24 h after inoculation with four 2-fold dilutions of each indicated virus using the Beta-Glo reporter assay. As shown in Fig. 8, we observed a 1- to 2-fold enhancement in viral infectivity when the T84V MA substitution was present in the context of wild-type MA proteins. We also observed a 1- to 3-fold enhancement in viral infectivity when the T84V MA substitution was present in the MA proteins of L13E or K32E viruses. In contrast to these slight augmentations in infectivity levels, we observed substantial enhancements in infectivity when the T84V substitution is present in the MA proteins of LAI-E99K and LAI-E99V viruses. Specifically, LAI-T84V/E99K particles were found to be 27- to 43-fold more infectious than the LAI-E99K virus at each dilution. Similarly, the E99V rescues ranged from a 29- to 39-fold enhancement at each titer. Although we found that a valine at residue 84 confers a slight enhancement in infectivity in most MA contexts, these data strongly suggest that the rescue observed in the context of an E99V or E99K MA substitution is unique and specific. Moreover, our findings implicate a novel functional relationship between residues 84 and 99 in MA, which is involved in Env incorporation and required for membrane fusion and virus infectivity.

Fig 8.

Infectivity of LAI-derived viruses with E99V or E99K MA substitutions is specifically enhanced by a T84V MA substitution. The data depict the fold improvement between viruses with and without the T84V substitution at four serial dilutions. Data shown are representative of four independent Beta-Glo infectivity assays performed in duplicate and analyzed at 24 h postinfection.

Truncated Env proteins can restore membrane fusion activity, but not infectivity, to LAI-E99V particles.

The reduced Env incorporation inherent to LAI-E99V and LAI-E99K particles is consistent with the notion that residue E99 may be important for MA-gp41 interactions during virus assembly. A reasonable prediction would be that the E99V MA- and E99K MA-mediated membrane fusion and infectivity defects might be suppressed by pseudotyping E99V or E99K particles with Env proteins that are truncated in the cytoplasmic tail (CT) domain of gp41. To test this possibility, we used PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis to introduce two consecutive stop codons into the gp41 coding sequence of pLAI-WT, pLAI-E99V, pLAI-E99K, pLAI-L13E, or pLAI-K32E. The Env proteins expressed from transfection of the resultant proviral clones (pLAI-Δ144, pE99V-Δ144, pE99K-Δ144, pL13E-Δ144, and pK32E-Δ144, respectively) contain a gp41 CT that is 6 rather than 150 amino acids in length (i.e., Δ144). 293T cells were individually transfected with pLAI-Δ144, pE99V-Δ144, pE99K-Δ144, pK32E-Δ144, pL13E-Δ144, the corresponding proviral clone with wild-type Env coding sequences, or pLAI-ΔEnv using cationic liposomes. Viruses in culture supernatants were harvested at 48 h posttransfection and normalized on the basis of RT activity as described above. Subsequently, TZM-bl cells were treated with an individual virus stock, and single-cycle infectivities were monitored at 24 h postinfection using the Beta-Glo assay system.

The infectivity values of the LAI-derived viruses with wild-type or truncated gp41 CT proteins, LAI-WT and LAI-Δ144, respectively, were assigned to represent 100%, and the values for all other viruses were adjusted accordingly. The normalized infectivity values for each virus with a full-length or a truncated gp41 CT that was tested are shown in Fig. 9A. We found that pseudotyping particles with truncated Env proteins could enhance the infectivity of viruses with amino acid substitutions in MA, albeit to various extents. The incorporation of Env proteins with a truncated gp41 CT rescued the infectivity defects associated with the L13E and K32E MA substitutions so that infectivity levels were comparable to those of WT-Δ144 viruses. In contrast, such pseudotyping of particles with an E99V or E99K MA substitution resulted in a slight enhancement of infectivity (2% to 7% and 2% to 16%, respectively). Based on these findings, we conclude that the infectivity defects associated with E99 MA substitutions cannot be suppressed by incorporation of truncated Env proteins.

Fig 9.

Truncated Env proteins can rescue membrane fusion but not the infectivity defect of LAI-derived particles with an E99V or E99K MA substitution. (A) Single-cycle infectivities of LAI-derived viruses with either full-length (blue bars, inoculated at 5K RTU/well) or truncated (red bars, inoculated at 2.5K RTU/well) HIV-1 Env were monitored in TZM-bl cells at 24 h postinfection using the Beta-Glo reporter assay. Infectivity of each mutant virus is based on the levels in LAI-WT or LAI-Δ144 infections, which represent 100% infectivity. The data shown are representative of four independent experiments performed in duplicate. (B) Equal RT units of the indicated viruses were used to infect MT-4 cells, and virus replication kinetics were monitored every other day for 11 days as described in the legend to Fig. 2B. Fresh cells and medium were added to each culture on day 7. The data shown are representative of two independent experiments performed in duplicate. (C) Virus-cell membrane fusion events were assayed in TZM-bl cells as described in the legend to Fig. 4. The data shown are representative of three independent experiments performed in duplicate.

Although low levels of virus infection were detected in TZM-bl cells incubated with E99V-Δ144 particles, it is possible that these viruses might retain the ability to initiate a spreading infection. To examine this possibility, we treated MT-4 cells with equivalent RT activity units of LAI-Δ144, E99V-Δ144, or LAI-ΔEnv. Cell culture supernatants were collected on alternating days and assayed for RT activity as described above. Data presented in Fig. 9B show that the ability of E99V-Δ144 particles to initiate a spreading infection is markedly reduced compared to that of LAI-Δ144 particles.

Lastly, we evaluated the fusion capacity of viruses pseudotyped with truncated gp41 CT proteins using the BLaM assay as described above. 293T cells were cotransfected with pBLaM-Vpr and pLAI-ΔEnv or an individual LAI proviral clone that encoded truncated Env proteins. TZM-bl cells were treated with equivalent amounts of each virus, and virus-cell membrane fusion was monitored as described for Fig. 4. Results from these virus-cell fusion assays are shown in Fig. 9C. Consistent with our infectivity data, we found that cells incubated with particles containing truncated Env and K32E- or L13E-substituted MA or WT MA proteins had comparable levels of BLaM activity. Strikingly, the levels of BLaM activity in cells treated with E99V-Δ144 or E99K-Δ144 particles were also comparable to those in cells treated with LAI-Δ144 particles throughout the duration of the assay. Thus, the robust ability to initiate virus-cell fusion detected by this assay suggests that truncated Env proteins were incorporated into E99V-Δ144 and E99K-Δ144 particles at levels comparable to the level in WT-Δ144 particles. Most important, our findings suggest that pseudotyping E99V or E99K particles with truncated Env proteins can restore membrane fusion capacity but is not sufficient to rescue viral infectivity.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrate that substitution of a highly conserved glutamate at residue 99 of the HIV-1 MA protein with either a valine or a lysine disrupts Env incorporation into particles and abrogates their ability to fuse with cell membranes. Using these mutant viruses, we show for the first time a direct correlation between major defects in both Env incorporation and virus-cell fusion. Furthermore, we find that the strain of HIV-1 can affect the magnitude of E99V-associated defects. The phenotypic similarity of LAI-E99V and LAI-E99K suggests that either a large hydrophobic or a basic residue in this position is sufficient to cause the observed impairments.

Residue 99 is located at the beginning of the MA C-terminal helix, a region that spans amino acids 96 through 121 (26). Similar to the N-terminal residues required for Env incorporation, residues at the beginning of the C-terminal helix may also associate with the plasma membrane. Previous mapping studies of anti-HIV-1 p17 MAbs, clones 32/5.8.42 and 32/1.24.89, identified direct interactions with MA residues 12 through 19, 17 through 22, and 100 through 105 (50). These data suggest that in the MA tertiary structure, the N-terminal basic domain is near the beginning of its C-terminal helix and that both regions are exposed to solvent. Subsequent structural analysis of MA identified K98 to be 1 of 12 surface-exposed basic residues that function as a membrane-binding surface of the protein (26). Moreover, another study suggests that MA residue T97 may be involved in phosphatidylinositol (4,5) bisphosphate (PIP2) binding at the cell membrane (57). Taken together, residues in these two domains appear to be in close proximity within the MA tertiary structure, as well as to the plasma membrane.

Several groups have shown that MA molecules can trimerize in solution (26, 39, 40). X-ray crystallographic studies of HIV-1 and simian immunodeficiency virus type 1 (SIV-1) MA proteins suggest that these trimers form a lattice structure containing an arrangement of spaces sufficient to accommodate the cytoplasmic tails of gp41 trimers (26, 53). Our results indicate that residue E99 plays an important role in Env incorporation during virus assembly. However, whether this residue is directly or indirectly involved in Env incorporation remains to be determined.

Residue 99 may have a direct function in Env incorporation via a specific interaction with viral glycoproteins. Given that E99 is solvent exposed, it might be considered a potential binding site for the C-terminal tail of gp41. Alternatively, this residue may interact with cellular or other viral proteins that facilitate an association between MA and Env. Such interactions might implicate E99 in the stabilization of Gag-Env complexes required for the retention of Env in virus particles. The human protein TIP47 has previously been reported to be involved in Gag-Env interactions (33). Although this study identified MA residues L12, W15, and E16 to be binding sites for TIP47, the authors noted that additional sites on MA may also be involved in TIP47 binding. Therefore, TIP47 might be a candidate for a cellular factor that selectively binds to E99.

Certain E99 substitutions might affect Env incorporation indirectly by preventing correct folding of the MA protein, thus disrupting virus assembly. On the basis of the MA structures shown in Fig. 6B, E99 appears to reside in the vicinity of a C-terminal hydrophobic pocket created by the N terminus of helix V packing along helix IV (7, 26). It has been suggested that instability in this pocket, which includes residues V84, Y86, I92, V94, A100, and K103, might compromise the overall structure of the core domain of MA (7). Using a molecular genetic approach, we identify a substitution at residue 84 of MA which compensates for the E99V-associated defects in the HIV-1 LAI strain. Additionally, we determined that the E99V-associated defects are less pronounced in a wild-type NL4.3 strain with a valine at position 84 of MA. While our structural analyses using PyMOL suggest that residues 84 and 99 may not interact directly, it is possible that glutamate 99 is necessary to stabilize the C-terminal hydrophobic pocket. This shared structural domain might explain how residue 84 can exert a selective effect on E99V MA-associated defects. Residue 99 has not been previously shown to contribute to the hydrophobic nature of this pocket. However, it may have an important role in maintaining the structure of MA suitable for Env incorporation.

Because our studies demonstrate that a valine at residue 84 of MA correlates with enhanced viral infectivity, it is somewhat surprising to find that a threonine is present more frequently at this position. Specifically, sequence alignment analyses of >1,100 MA proteins from HIV-1 group M, representing subtype A through K viruses, reveals a threonine and a valine in this position in 82% and 17% of the strains, respectively (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). We also find it intriguing that two amino acids with vastly different chemical and structural properties are present at one position in over 99% of the documented strains. Given these findings, we hypothesize that the enhanced viral infectivity conferred by V84 in tissue culture assays may not be recapitulated with in vivo infections, and thus, this amino acid would not confer a replicative advantage. For example, if a valine at residue 84 of MA markedly enhances first-round infectivity in vivo, then the incidence of multiple viruses infecting a single cell could be increased. Such superinfection events, rather than the entry of a single virus particle, might be more readily detected by the host cell antiviral mechanisms. As a result of detection, programmed cell death pathways may be activated prior to the release of nascent particles, which, ultimately, might be detrimental for long-term viral fitness. Alternatively, a valine residue at position 84 of MA may cause discrete structural changes that enhance infectivity in tissue culture cells, yet it might promote the creation of epitopes that are effectively neutralized by the host immune system.

There are two issues related to the phenotype of the NL4.3-E99V virus that warrant further consideration. First, it is unclear why this mutant virus, which has a valine at position 84, displays an infectivity defect. It is possible that other nonconservative amino acid differences in LAI-MA and NL4.3-MA, specifically, those at positions 28, 124, and 125, may contribute to the observed phenotypic variation. Although these residues lay outside the hydrophobic pocket mentioned above, they could, in combination with the E99V substitution, have a role in the overall stabilization of the MA globular head domain and its ability to incorporate Env during assembly. Given that residue 28 is located in the globular head domain, it would be interesting to exchange this residue in LAI with that of NL4.3 and vice versa to determine whether the level of Env incorporation associated with NL4.3-E99V can be restored to wild-type levels. Additionally, one might identify and evaluate potential amino acid differences within the second α helix of the NL4.3 and LAI gp41 C-terminal tails, as this region has been specifically implicated to interact with MA (42, 67).

Second, a very low level of virus-cell fusion was detected with the NL4.3-E99V virus. The Beta-Glo assay results for this NL4.3-E99V virus at 48 h compared to those at 24 h suggest a possible delay in virus infectivity. This possible delay may occur at the virus-cell fusion step, which might explain why minimal fusion events were detected at the time points examined. Higher levels of BLaM activity might be detectable in cells after extended incubation with NL4.3-E99V, but not with LAI-E99V.

Lastly, we have shown that incorporation of Env proteins with truncated gp41 CT domains restores membrane fusion capacity but not infectivity to E99V or E99K MA particles. Because MA has been implicated in a number of postentry steps, it is possible that the E99 of MA has a previously undiscovered role in uncoating, reverse transcription, PIC migration, or nuclear import via interactions with cellular cofactors or viral proteins within the HIV core (5, 8, 19, 24, 28, 29, 55, 64, 70). Alternatively, E99 might be involved, directly or indirectly, in the dissociation of MA molecules from the PM and in conformational changes that promote sequestration of the myristoyl moiety. Disruption in MA membrane detachment during early events could have particular consequences that prevent the production of infectious particles. For example, the inability to dissociate from the PM might inhibit the intracellular migration of the reverse transcription complex (RTC) to the nucleus. In addition, uncoating of the viral capsid may depend on its location within the host cell, and thus, membrane tethering might significantly impair the efficiency of this early step. Similarly, sequestration at the cellular periphery could expose the viral core to degradation by cellular proteolytic pathways.

We have demonstrated that the highly conserved glutamate at position 99 in HIV-1 MA has an essential function in Env incorporation during virus assembly and, potentially, a previously unrecognized role in postentry events. Collectively, our findings implicate a novel region of MA, the C-terminal hydrophobic pocket, in mediating these key processes. Additional functional and structural analyses of residues in this understudied region of MA might facilitate development of small-molecule inhibitors of Env incorporation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank P. Clapham, H. Göttlinger, G. Melikyan, P. Peters, T. Schmidt, and M. Zapp for protocols, technical assistance, and advice. We thank members of the Stevenson lab, especially S. Swingler, M. Sharkey, and N. Sharova, for scientific discussion and advice. The Chessie 8 antibody was obtained from P. Clapham, and the BLaM-Vpr plasmid was obtained from Warner Greene of the Gladstone Institute. Cell lines were obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (NIAID, NIH). We acknowledge the University of Massachusetts Center for AIDS Research Molecular Biology Core and the University of Massachusetts Molecular Biology Laboratories for oligonucleotide synthesis, DNA sequence analyses, and reagents. We are grateful to M. Duenas-Decamp for assistance using the PyMOL program and E. L. W. Kittler and M. Zapp for assistance during manuscript preparation.

This work was supported by NIH grants AI32890 and AI37475 to M.S.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 7 December 2011

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asmusa.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Adachi A, et al. 1986. Production of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated retrovirus in human and nonhuman cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone. J. Virol. 59:284–291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alfadhli A, Still A, Barklis E. 2009. Analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix binding to membranes and nucleic acids. J. Virol. 83:12196–12203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bhatia A, Campbell N, Panganiban A, Ratner L. 2007. Characterization of replication defects induced by mutations in the basic domain and C-terminus of HIV-1 matrix. Virology 369:47–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bhattacharya J, Repik A, Clapham PR. 2006. Gag regulates association of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope with detergent-resistant membranes. J. Virol. 80:5292–5300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bukrinsky MI, et al. 1993. A nuclear localization signal within HIV-1 matrix protein that governs infection of non-dividing cells. Nature 365:666–669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Camaur D, Gallay P, Swingler S, Trono D. 1997. Human immunodeficiency virus matrix tyrosine phosphorylation: characterization of the kinase and its substrate requirements. J. Virol. 71:6834–6841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cannon PM, et al. 1997. Structure-function studies of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix protein, p17. J. Virol. 71:3474–3483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Casella CR, Raffini LJ, Panganiban AT. 1997. Pleiotropic mutations in the HIV-1 matrix protein that affect diverse steps in replication. J. Virol. 228:294–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cavrois M, De Noronha C, Greene WC. 2002. A sensitive and specific enzyme-based assay detecting HIV-1 virion fusion in primary T lymphocytes. Nat. Biotechnol. 20:1151–1154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cosson P. 1996. Direct interaction between the envelope and matrix proteins of HIV-1. EMBO J. 15:5783–5788 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Davis M, Jiang J, Zhou J, Freed EO, Aiken C. 2006. A mutation in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein destabilizes the interaction of envelope protein subunits gp120 and gp41. J. Virol. 80:2405–2417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. DeLano WL. 2002The PYMOL user's manual. http://www.pymol.org Delano Scientific, San Carlos, CA [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dorfman T, Mammano F, Haseltine WA, Göttlinger HG. 1994. Role of the matrix protein in the virion association of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein. J. Virol. 68:1689–1696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dupont S, et al. 1999. A novel nuclear export activity in HIV-1 matrix protein required for viral replication. Nature 402:681–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fäcke M, Janetzko A, Shoeman RL, Kräusslich HG. 1993. A large deletion in the matrix domain of the human immunodeficiency virus gag gene redirects virus particle assembly from the plasma membrane to the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Virol. 67:4972–4980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fassati A, Goff SP. 2001. Characterization of intracellular reverse transcription complexes of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 75:3626–3635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Freed EO. 1998. HIV-1 gag proteins: diverse functions in the virus life cycle. Virology 251:1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Freed EO, Englund G, Martin MA. 1995. Role of the basic domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix in macrophage infection. J. Virol. 69:3949–3954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Freed EO, Orenstein JM, Buckler-White AJ, Martin MA. 1994. Single amino acid changes in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix protein block virus particle production. J. Virol. 68:5311–5320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Freed EO, Martin MA. 1995. Virion incorporation of envelope glycoproteins with long but not short cytoplasmic tails is blocked by specific, single amino acid substitutions in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix. J. Virol. 69:1984–1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Freed EO, Martin MA. 1996. Domains of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix and gp41 cytoplasmic tail required for envelope incorporation into virions. J. Virol. 70:341–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gallay P, Swingler S, Song J, Bushman F, Trono D. 1995. HIV nuclear import is governed by the phosphotyrosine-mediated binding of matrix to the core domain of integrase. Cell 83:569–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Göttlinger HG, Sodroski JG, Haseltine WA. 1989. Role of capsid precursor processing and myristoylation in morphogenesis and infectivity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86:5781–5785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Haffar OK, Popov S, Dubrovsky L, Agostini I, Tang H. 2000. Two nuclear localization signals in the HIV-1 matrix protein regulate nuclear import of the HIV-1 pre-integration complex. J. Mol. Biol. 299:359–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hannah R, Stroke I, Betz N. 2003. Beta-Glo® assay system: a luminescent β-galactosidase assay for multiple cell types and media. Cell Notes 6:16–18 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hill CP, Worthylake D, Bancroft DP, Christensen AM, Sundquist WI. 1996. Crystal structures of the trimeric human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix protein: implications for membrane association and assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:3099–3104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kaplan AH, Swanstrom R. 1991. HIV-1 gag proteins are processed in two cellular compartments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 88:4528–4532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kaushik R, Ratner L. 2004. Role of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix phosphorylation in an early postentry step of virus replication. J. Virol. 78:2319–2326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kiernan RE, Ono A, Englund G, Freed EO. 1998. Role of matrix in an early postentry step in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 life cycle. J. Virol. 72:4116–4126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kunkel TA, Roberts JD, Zakour RA. 1987. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Methods Enzymol. 155:16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lee YM, Tang XB, Cimakasky LM, Hildreth JE, Yu XF. 1997. Mutations in the matrix protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 inhibit surface expression and virion incorporation of viral envelope glycoproteins in CD4+ T lymphocytes. J. Virol. 71:1443–1452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lodge R, Göttlinger HG, Gabuzda D, Cohen EA, Lemay G. 1994. The intracytoplasmic domain of gp41 mediates polarized budding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in MDCK cells. J. Virol. 68:4857–4861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lopez-Verges S, Camus G, Blot G, Beauvoir R, Benearous R. 2006. Tail-interacting protein TIP47 is a connector between Gag and Env and is required for Env incorporation into HIV-1 virions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:14947–14952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mammano F, et al. 1997. Truncation of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein allows efficient pseudotyping of Moloney murine leukemia virus particles and gene transfer into CD4+ cells. J. Virol. 71:3341–3345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mammano F, Kondo E, Sodroski J, Bukovsky A, Göttlinger HG. 1995. Rescue of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix protein mutants by envelope glycoproteins with short cytoplasmic domains. J. Virol. 69:3824–3830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Massiah MA, et al. 1996. Comparison of the NMR and X-ray structures of the HIV-1 matrix protein: evidence for conformational changes during viral assembly. Protein Sci. 5:2391–2398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Miller MD, Farnet CM, Bushman FD. 1997. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 preintegration complexes: studies of organization and composition. J. Virol. 71:5382–5390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Miyauchi K, Kim Y, Latinovic O, Morozov V, Melikyan GB. 2009. HIV enters cells via endocytosis and dynamin-dependent fusion with endosomes. Cell 137:433–444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Morikawa Y, et al. 1996. Complete inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus Gag myristoylation is necessary for inhibition of particle budding. J. Biol. Chem. 271:2868–2873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Morikawa Y, Zhang W, Hockley D, Nermut M, Jones I. 1998. Detection of a trimeric human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag intermediate is dependent on sequences in the matrix domain, p17. J. Virol. 72:7659–7663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Murakami T, Ablan S, Freed EO, Tanaka Y. 2004. Regulation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Env-mediated membrane fusion by viral protease activity. J. Virol. 78:1026–1031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Murakami T, Freed EO. 2000. Genetic evidence for an interaction between human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix and helix 2 of the gp41 cytoplasmic tail. J. Virol. 74:3548–3554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Murakami T, Freed EO. 2000. The long cytoplasmic tail of gp41 is required in a cell type-dependent manner for HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein incorporation into virions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:343–348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nermut M, et al. 1994. Fullerene-like organization of HIV Gag protein shell in virus-like particles produced by recombinant baculovirus. Virology 198:288–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ono A, Ablan SD, Lockett SJ, Nagashima K, Freed EO. 2004. Phosphatidylinositol (4,5) bisphosphate regulates HIV-1 Gag targeting to the plasma membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:14889–14894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ono A, Freed EO. 1999. Binding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag to membrane: role of the matrix amino terminus. J. Virol. 73:4136–4144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ono A, Huang M, Freed EO. 1997. Characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix revertants: effects on virus assembly, Gag processing, and Env incorporation into virions. J. Virol. 71:4409–4418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ono A, Orenstein JM, Freed EO. 2000. Role of the Gag matrix domain in targeting human immunodeficiency virus type 1 assembly. J. Virol. 74:2855–2866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Paillart J, Göttlinger HG. 1999. Opposing effects of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag to membrane: role of the matrix amino terminus. J. Virol. 73:2604–2612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Papsidero LD, Sheu M, Ruscetti FW. 1989. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1-neutralizing monoclonal antibodies which react with p17 core protein: characterization and epitope mapping. J. Virol. 63:267–272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Peden K, Emerman M, Montagnier L. 1991. Changes in growth properties on passage in tissue culture of viruses derived from infectious molecular clones of HIV-1LAI, HIV-1MAL, and HIV-1ELI. Virology 185:661–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Poiesz BJ, et al. 1980. Detection and isolation of type C retrovirus particles from fresh and cultured lymphocytes of a patient with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 77:7415–7419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Rao Z, et al. 1995. Crystal structure of SIV matrix antigen and implications for virus assembly. Nature 378:743–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Reicin AS, Kaplana G, Paik S, Marmon S, Goff S. 1995. Sequences in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 U3 region required for in vivo and in vitro integration. J. Virol. 69:5904–5907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Reicin A, Ohagen A, Yin L, Hoglund S, Goff S. 1996. The role of Gag in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virion morphogenesis and early steps of the viral life cycle. J. Virol. 70:8645–8652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Reil H, Bukovsky AA, Gelderblom HR, Göttlinger HG. 1998. Efficient HIV-1 replication can occur in the absence of the viral matrix protein. EMBO J. 17:2699–2708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Saad JS, et al. 2006. Structural basis for targeting HIV-1 Gag proteins to the plasma membrane for virus assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:11364–11369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Saad JS, et al. 2007. Point mutations in the HIV-1 matrix protein turn off the myristyl switch. J. Mol. Biol. 366:574–585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Scarlata S, Ehrlich L, Carter C. 1998. Membrane-induced alterations in HIV-1 Gag and matrix protein-protein interactions. J. Mol. Biol. 277:161–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Swingler S, et al. 1997. The Nef protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 enhances serine phosphorylation of the viral matrix. J. Virol. 71:4372–4377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Takeuchi Y, McClure MO, Pizzato M. 2008. Identification of gammaretroviruses constitutively released from cell lines used for human immunodeficiency virus research. J. Virol. 82:12585–12588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tang C, Ndassa Y, Summers MF. 2002. Structure of the N-terminal 283-residue fragment of the immature HIV-1 Gag polyprotein. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9:537–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Tang C, et al. 2004. Entropic switch regulates myristate exposure in the HIV-1 matrix protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:517–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Von Schwedler U, Kornbluth RS, Trono D. 1994. The nuclear localization signal of the matrix protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 allows the establishment of infection in macrophages and quiescent T lymphocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91:6992–6996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wei X, et al. 2002. Emergence of resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in patients receiving fusion inhibitor (T-20) monotherapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1896–1905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Welker R, Hohenberg H, Tessmer U, Huckhagel C, Krausslich HG. 2000. Biochemical and structural analysis of isolated mature cores of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 74:1168–1177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. West JT, et al. 2002. Mutation of the dominant endocytosis motif in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 can complement matrix mutations without increasing Env incorporation. J. Virol. 76:3338–3349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Wyma DJ, Kotov A, Aiken C. 2000. Evidence for a stable interaction of gp41 with Pr55Gag in immature human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particles. J. Virol. 74:9381–9387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wyma DJ, et al. 2004. Coupling of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 fusion to virion maturation: a novel role of the gp41 cytoplasmic tail. J. Virol. 78:3429–3435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Yu X, Yu QC, Lee TH, Essex M. 1992. The C terminus of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix protein is involved in early steps of the virus life cycle. J. Virol. 66:5667–5670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Yu X, Yuan X, Matsuda Z, Lee TH, Essex M. 1992. The matrix protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is required for incorporation of viral envelope protein into mature virions. J. Virol. 66:4966–4971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Yu Z, et al. 2005. The cellular HIV-1 Rev cofactor hRIP is required for viral replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:4027–4032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Zhou W, Resh M. 1996. Differential membrane binding of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix protein. J. Virol. 70:8540–8548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.