Abstract

The group of closely related avian sarcoma and leukosis viruses (ASLVs) evolved from a common ancestor into multiple subgroups, A to J, with differential host range among galliform species and chicken lines. These subgroups differ in variable parts of their envelope glycoproteins, the major determinants of virus interaction with specific receptor molecules. Three genetic loci, tva, tvb, and tvc, code for single membrane-spanning receptors from diverse protein families that confer susceptibility to the ASLV subgroups. The host range expansion of the ancestral virus might have been driven by gradual evolution of resistance in host cells, and the resistance alleles in all three receptor loci have been identified. Here, we characterized two alleles of the tva receptor gene with similar intronic deletions comprising the deduced branch-point signal within the first intron and leading to inefficient splicing of tva mRNA. As a result, we observed decreased susceptibility to subgroup A ASLV in vitro and in vivo. These alleles were independently found in a close-bred line of domestic chicken and Indian red jungle fowl (Gallus gallus murghi), suggesting that their prevalence might be much wider in outbred chicken breeds. We identified defective splicing to be a mechanism of resistance to ASLV and conclude that such a type of mutation could play an important role in virus-host coevolution.

INTRODUCTION

Retroviruses enter the host cell through specific receptors, cell surface proteins with high affinity to viral envelope glycoproteins. The interaction between receptors and viral glycoproteins is very complex and includes the initial attachment of the virion, profound conformational changes in the structure of the viral glycoprotein, exposure of fusion peptides, and, ultimately, the fusion of viral and cellular membranes (5, 47). Despite the strict structural requirements for these interactions, hypervariability of retroviral glycoproteins can change the receptor usage and broaden the host range. Indeed, closely related families of retroviruses have evolved into multiple subgroups that utilize different cellular surface proteins as receptors. For example, the group of avian alpharetroviruses avian sarcoma and leukosis viruses (ASLVs) comprise 10 related subgroups, A to J, which either do not interfere at all with each other or interfere only nonreciprocally in infecting chicken cells. The susceptibility of chicken cells to highly related ASLV subgroups A to E is determined by three genetic loci, tva, tvb, and tvc (5, 41). The Tva protein belongs to the family of low-density lipoprotein receptors (LDLRs) (6, 48) and determines susceptibility to the subgroup A ASLVs. The tumor necrosis factor receptor-related protein Tvb confers susceptibility to subgroup B, D, and E ASLVs by three nonoverlapping binding sites (2, 3, 8), and the Tvc protein, closely related to the mammalian butyrophilins, serves as receptor for C subgroup ASLV (14).

The rapid evolution of novel retrovirus envelopes is compelled by the appearance of host entry restrictions. Genetic alterations of specific receptor loci can cause complete lack of the receptor protein or expression of an aberrant protein with decreased affinity for the retroviral envelope protein. Resistance alleles have been identified in all three tva, tvb, and tvc receptor loci, and premature termination codons or frameshift mutations were found behind these resistances (13, 14, 25). Even single-amino-acid substitutions can cause the resistance when cysteine residues are affected and the basic receptor structure is changed (13). In general, slight structural changes affecting the virus binding sites but keeping the normal cellular functions of receptor molecules could be the starting point for coevolution of the retrovirus and the host cell. Decreased affinity for the respective envelope protein creates selective pressure against the retrovirus and favors its escape variants that evolved toward at least low affinity to alternative cell surface molecules. Subsequent accommodation of envelope proteins can result in complete changes of receptor usage and cellular tropism. Whereas escape mutants of ASLVs with expanded viral receptor usage were already selected on cocultivated permissive and nonpermissive cells (34, 38) or exerted by the presence of soluble competitor Tva (27), the natural occurrence of receptor variants with decreased susceptibility to ASLV infection remains to be explored. As a proof of the principle, we have identified a single-amino-acid substitution in the Tvb receptor that results in reduced susceptibility to ASLV subgroups B and D and resistance to subgroup E (35).

In order to identify further alleles of ASLV receptors, we screened a panel of chicken lines (33) for phenotypes of reduced but not completely eliminated susceptibility to specific subgroups. We describe here the decreased susceptibility to ASLV subgroup A in a close-bred chicken line and respective molecular defects in the tva locus. Two independent deletions comprising the branch point within the first intron lead to inefficient splicing of tva mRNA. The same intronic deletions were also found in a subspecies of red jungle fowl, Gallus gallus murghi. The frequent disruption of splicing signals resembles the situation in the low-density lipoprotein receptor gene, a human homologue of chicken tva, in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia (12, 40). We conclude that ASLV receptor alleles determining the decreased sensitivity to avian retroviruses are common in the population of domestic chick as well as in wildfowl and could play an important role in virus-host coevolution.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals.

The close-bred chicken line P free of ev loci (18), the inbred lines CC.R1, CB, and L15 (33), and the outbred chicken population Brown Leghorn (33) have been maintained at the Institute of Molecular Genetics, Prague, Czech Republic. Hens and cockerels were kept separately in individual cages with food and water provided ad libitum. The photoperiod of 12 h light and 12 h dark was applied. Four embryonated eggs of the red jungle fowl subspecies Gallus gallus murghi were obtained from the zoological garden Ohrada u Hluboké, Czech Republic. Breeding pairs kept in this zoo are direct descendants of animals introduced from a remote border area of Assam, India. A low probability of interbreeding of free-ranging G. g. murghi birds with domestic chicks was demonstrated (23). Incubation of embryonated eggs was performed at 38°C and 60% relative humidity in a forced-air incubator with a tilting motion through a 90° angle every 2 h.

Cell culture and virus propagation.

Chicken embryo fibroblasts (CEFs) were prepared from ten 10-day-old embryos from lines P, L15, and CB and individually from four embryos of G. g. murghi. The procedure was described previously (15). CEFs as well as chicken permanent cell line DF-1 (19) were grown in a mixture of two parts of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium and one part of F-12 medium supplemented with 5% calf serum (CS), 5% fetal calf serum, 1% chicken serum, and penicillin/streptomycin (100 μg/ml each) in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C. RCASBP(A)GFP and RCASBP(B)GFP subgroup A and B viruses, respectively (15, 21), transducing the green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter gene were prepared by plasmid DNA transfection into DF-1 cells, which are free of avian leukosis virus (ALV)-related endogenous retroviral loci. Infection and virus spread were observed as an increasing proportion of GFP-positive cells, and virus stocks were obtained on day 4 or 5 posttransfection (p.t.). The cell supernatants were cleared of debris by centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 10 min at 10°C, and aliquoted viral stocks were stored at −80°C. The titers were quantitated by terminal dilution and infection of fresh DF-1 cells and reached 106 infection units (IU) per ml.

The transforming subgroup A and B ASLVs for in vivo sarcoma induction were generated by the rescue of replication-defective and v-src-containing Bryan high-titer Rous sarcoma virus, which is present in the transformed 16Q quail cell line (28), by either A or B subgroup RCASBPGFP. The rescue was done by mixing the RCASBPGFP-infected DF-1 cells with 16Q cells as described by Reinišová et al. (35). The titers of rescued transforming A and B subgroup avian sarcoma viruses (ASVs) were estimated by a focus assay in Brown Leghorn CEFs and reached titers of 104 and 4 × 103 focus-forming units (FFU) per ml, respectively.

Virus spread assayed by flow cytometry.

CEFs of line P and G. g. murghi were seeded at a density of 5 × 104 per well in a 24-well plate and infected with 5 × 105 IU of either RCASBP(A)GFP or RCASBP(B)GFP virus 24 h after seeding. The virus was applied in 0.25 ml medium for 1 h. The percentage of GFP-positive cells was quantitated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) using an LSRII analyzer (Beckton Dickinson) on days 1, 2, 3, 4, and 7 postinfection. Each day, the cells of three wells were trypsinized, washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and analyzed. For the analysis on the seventh day, the cells were passaged 1:4 on a new plate on the fifth day and measured 48 h later.

In vivo sarcoma induction and monitoring.

Ten-day-old chickens from lines P and CC.R1 were inoculated with 100 FFU of transforming subgroup A or B ASLV rescued from 16Q cells in 0.1 ml of Iscove's Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium into the pectoral muscle. The growth of tumors palpable at the site of inoculation was monitored either by weighing the whole tumor after surgery or noninvasively by calculating the area of prominent tumor. The contours of the tumor were traced on transparent foil, and the area of the tumor was calculated in mm2 (36). Birds with vast progressively growing tumors were sacrificed well before they reached the terminal stage.

Amplification and analysis of tva alleles from line P and G. g. murghi.

We prepared total RNA and genomic DNA from DF-1 cells, cultured line P CEFs, and G. g. murghi CEFs using the Tri Reagent (Sigma) and phenol-chloroform extraction, respectively. cDNA was obtained by reverse transcription of 1 μg total RNA with Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (RT) and oligo(dT)15 primers (both from Promega). We amplified the whole tva coding sequence using the forward TVA4 primer 5′-GCATGGTGCGGTTGTTGGAG-3′, containing the tva initiation codon, and reverse TVA5 primer 5′-TCGTGTCCAAATTCAGCCAG-3′, complementary to the 3′ untranslated region (UTR). PCR conditions were the following: 98°C for 90 s; 34 cycles of 98°C for 10 s, 62°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 45 s; and terminal extension at 72°C for 5 min with Taq polymerase (TaKaRa). The DNA sequence of exon 1, intron 1, and exon 2 was amplified from 100 ng chromosomal DNA using the forward TVA4 primer and reverse TVA6 primer 5′-GGGATCGCGCGGCTCCGAAC-3′ in the left part of exon 2. PCR conditions were the following: 95°C for 3 min; 34 cycles of 94°C for 20 s, 58°C for 40 s, and 72°C for 40 s; and terminal extension at 72°C for 5 min with Taq polymerase (TaKaRa). The final PCR product with an expected length of 331 bp was treated with ExoSAP-IT (USB) and then sequenced using a BigDye Terminator (version 3.1) cycle sequencing kit (PE Applied Biosystems).

Construction of tva expression plasmids and transfection experiments.

Expression forms of tva from L15 and P chicken lines were cloned by PCR in a 50-μl reaction mixture of 1× GC buffer (Finnzymes) and 3% dimethyl sulfoxide with 1 U of Phusion Hot Start high-fidelity DNA polymerase (Finnzymes), 200 ng of chromosomal DNA from either L15 or P line CEFs, and forward TVAK2L primer 5′-CAGCTCGAGGTCGTCCAT-3′ in the tva 5′ UTR and reverse TVAK3R primer 5′-GGAAGGCCCTGTCCTATTTC-3′ in the tva 3′ UTR, which amplify the entire tva coding sequence. Cycling conditions were the following: 98°C for 60 s; 30 cycles of 98°C for 7 s, 64°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 105 s; and terminal extension at 72°C for 7 min. PCR products of 3.4 kbp in length were purified using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen), 3′-terminal AA dinucleotides were added, and products were ligated into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega). Specific clones of tva from the P line (tva-P) and tva-L15 were selected by EcoRI and KpnI digestion. The tva fragments were cut out using EcoRI and ligated into the digested and dephosphorylated pcDNA3/EcoRI vector. Resulting clones with the proper orientation of tva-P and tva-L15 inserts were used for the transfer of coding sequences as XhoI fragments into the pVITROtdTomato expression vector, and pcDNA3-tva-P was also used as a quantitative PCR (qPCR) external standard. The pVITROtdTomato vector was created from the pVitro expression construct (InvivoGene) by replacement of the GFP coding sequence with the tdTomato fluorescence marker in the first expression cassette. The final expression constructs, pVITROtdTomato-tvaP and pVITROtdTomato-tvaL15, were used in transfection experiments. CEFs (4 × 105) from the CB, P, and L15 lines were seeded onto 6-well plates in the medium without antibiotics. Transfection was done 12 h later using a mix of 6 μl FuGENE HD transfection reagent (Roche) and 2 μg of plasmid in Opti-MEM medium (Gibco BRL) in a total volume of 100 μl. In low-dose transfection experiments, the small amounts of pVITROtdTomato-tvaP and pVITROtdTomato-tvaL15 plasmids were supplemented to up to 2 μg with the empty vector pcDNA3. At 12 h p.t., the medium was changed, and at 24 h p.t., the cells were used for infection and subsequent FACS. Only cells expressing the red tdTomato fluorescent protein marker were gated for GFP analysis to normalize the transfection efficiency.

Splice-specific quantitative RT-PCR.

Total RNAs from L15 and P line CEFs were isolated by RNAzol RT (Molecular Research Center) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Two micrograms of total RNA was DNase treated for 15 min and reverse transcribed in a total volume of 25 μl with Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Gibco) and random hexamers for priming. One microliter of the resulting cDNA was then used for the quantitative PCR based on the MESA GREEN qPCR MasterMix Plus for SYBR assay kit (Eurogentec) and a Chromo4 system for real-time PCR detection (Bio-Rad). Quantifications were performed for the tva transcript with retained intron 1, the tva transcript with spliced intron 1, and the chicken GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) gene as a housekeeping reference gene. The volume of the reaction mixture was 20 μl with a 400 nM final concentration of each primer: tva-E1-FW (5′-GGTTGTTGGAGCTGCTGGT-3′), tva-E2-RV (5′-CACTCCAGCGGGTAGCAGTC-3′), tva-I1-RV (5′-ATCCAACGTGGGGAGAGGAC-3′), chGAPDH-FW (5′-CATCGTGCACCACCAACTG-3′), and chGAPDH-RV (5′-CGCTGGGATGATGTTCTGG-3′). An expression plasmid containing tva-P cloned into the pcDNA3 vector was used as an external standard for the tva transcript with retained intron 1. The external standard for tva with spliced intron 1 was constructed by PCR using L15 cDNA and transcript-specific primer sets (tva-E1-FW, tva-E2-RV). Resulting PCR fragments of tva with spliced intron 1 were cloned into pGEM-T Easy (Promega) and verified by sequencing. Tenfold serial dilutions of plasmids containing the retained or spliced intron 1 of tva ranging from 10 to 106 copies per reaction mixture were used for construction of the calibration curves. Tenfold serial dilutions of plasmid containing the fragment of GAPDH gene cloned into the pGEM-T Easy plasmid (Promega) ranging from 10 to 106 copies per reaction mixture were used for construction of the calibration curve with GAPDH. We normalized the numbers of RNA molecules placed in the reaction mixture according to the number of GAPDH transcripts. Cycling conditions for tva fragments with retained intron (primers tva-E1-FW and tva-I1-RV) and GAPDH were 95°C for 15 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s for 40 cycles; cycling conditions for tva fragments with spliced intron (primers tva-E1-FW and tva-E2-RV) and GAPDH were 95°C for 15 s, 63°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s for 40 cycles. The negative controls included water as a template. All quantitative RT-PCRs were performed in triplicate. The specificity of the PCR products amplified was confirmed by melting curve analysis and by sequencing the PCR products. To assess the amount of contaminating exogenous DNA, either genomic or plasmid, we included reactions run in the absence of RT as negative controls. The background values of these negative controls were subtracted from the results of respective reactions with RT.

Quantitation of Tva display by secreted immunoadhesin SU(A)-rIgG.

The immunoadhesin SU(A)-rIgG (49), which combines the receptor-binding parts of the subgroup A SU glycoprotein with the IgG heavy chain, cloned as the SUATEVrIgG sequence into the ClaI site of RCASBP(B), was obtained from Mark J. Federspiel (Molecular Medicine Program, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN). The immunoadhesin was produced as a crude supernatant of SUATEVrIgG-transfected DF-1 cells (20). CEFs of the chicken lines CB, L15, and P were harvested by 0.25% trypsin–EDTA solution and washed with PBS. Cells (2 × 106) in 0.1 ml of PBS supplemented with 2% calf serum (PBS–2% CS) were mixed with 0.9 ml of supernatant from SUATEVrIgG-transfected DF-1 cells, and the mixture was incubated on ice for 60 min. CEFs were then washed with PBS–2% CS and incubated with 1 μl of goat anti-rabbit IgG linked to Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen) in PBS–4% CS in a total volume of 1 ml on ice for 30 min. The complexes of cells with immunoadhesins were washed with PBS–2% CS, resuspended in 150 μl PBS–2% CS, and quantitated by FACS using an LSRII analyzer (Becton Dickinson).

RESULTS

Reduced susceptibility to subgroup A ASLV in inbred chicken lines and wild jungle fowl.

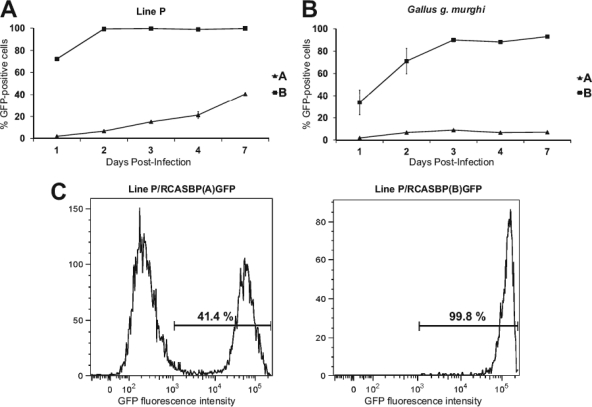

We previously identified a single-amino-acid substitution in the Tvb receptor that resulted in reduced susceptibility to ASLV subgroups B and D and resistance to subgroup E (35). This finding implies the existence of similar genetic variations within other ASLV receptor loci, and inbred lines of domestic chicken can manifest the phenotype of such recessive alleles. We therefore analyzed the susceptibility to the subgroup A ASLV in the panel of 12 inbred and close-bred chicken lines available at the Institute of Molecular Genetics in Prague (33) and, for comparison, the Indian red jungle fowl (G. g. murghi) in an in vitro kinetic assay (35). CEFs of defined origin were infected with replication-competent reporter ASLV vector RCASBP(A)GFP, and the percentage of GFP-positive cells was quantified by flow cytometry on seven subsequent days. Line P was analyzed in more detail because of the decreased susceptibility to the subgroup A ASLV (Fig. 1A). RCASBP(A)GFP infected line P CEFs inefficiently, with only ca. 2% of the cells being infected on day 1, and the virus spread slowly, reaching 20% of infected cells on day 4 and 40% on day 7. The GFP-negative and GFP-positive cells are clearly distinct, as shown by the presence of two separated peaks in the FACS histogram (Fig. 1C). Line P is susceptible to subgroup B, and the GFP reporter virus RCASBP(B)GFP was used as a positive control. As expected, this virus infected line P CEFs very efficiently, with more than 70% of the cells being infected on day 1, and spread quickly, reaching virtually complete infection of cells by day 2 (Fig. 1A and C). CEFs prepared from four individual G. g. murghi embryos were even less susceptible to subgroup A ASLV than line P. RCASBP(A)GFP infected only 2% of G. g. murghi CEFs on day 1, and the percentage of GFP-positive cells reached the maximum of 8% on day 3. RCASBP(B)GFP infected 33% of G. g. murghi CEFs on day 1 and then spread quickly, infecting up to 86% on day 3 and remaining at between 80% and 90% on days 4 to 7 (Fig. 1B). In conclusion, we demonstrated inefficient infection and slow spread of the ALV A subgroup in line P and G. g. murghi in vitro. This resembles the decreased susceptibility for the ALV B subgroup in line M (35).

Fig 1.

Time course of infection of line P (A) and G. g. murghi (B) CEFs with ASLVs. CEFs were infected at a multiplicity of infection of 10 with replication-competent ASLVs encoding the GFP reporter proteins RCASBP(A)GFP and RCASBP(B)GFP. The percentage of GFP-positive cells was determined by FACS on the indicated day postinfection as a mean of three parallel dishes. (C) FACS histograms of line P CEFs infected with RCASBP(A)GFP (left) and RCASBP(B)GFP (right) at 7 days postinfection. Line P CEFs were prepared as a mix from 10 embryos, G. g. murghi CEFs were prepared from 4 individual embryos, and representative results from 1 embryo are shown. The relative GFP fluorescence is plotted against the cell count, and the percentage of GFP-positive cells is indicated as a mean of three parallel dishes. Error bars show standard deviations wherever they are large enough to be visible.

Inefficient sarcoma induction by subgroup A ASV in line P chickens.

To confirm the in vitro reduced susceptibility of line P CEFs to the subgroup A ALV, we infected line P chickens with transforming subgroup A and B ASVs and monitored the induction and growth of sarcomas. Subgroup A and B ASVs transducing the v-src oncogene were generated and produced by complementation of an env-defective and v-src-containing virus from the 16Q cell line with either the A or B subgroup of RCASBPGFP virus. Ten-day-old line P chicks were inoculated with 100 FFU into the pectoral muscle, and the incidence and weight of the sarcoma at the site of inoculation were quantitated. In accordance with the in vitro experiment, line P was fully susceptible to sarcoma induction by subgroup B ASV, and in a cohort of eight chicks, all birds developed sarcomas growing progressively and requiring termination of six birds by days 21 to 28 postinoculation (p.i.) and one bird on day 35 p.i. One bird with sarcoma died prematurely of nonspecific causes (Table 1). The susceptibility to subgroup A ASV was decreased, as in a cohort of eight chicks, two birds did not develop sarcomas at all and six birds developed slowly growing tumors tending to regression during the experiment. Only four birds kept small tumors on days 35 to 42 p.i., when the experiment was terminated. As a control, we inoculated five chicks of the line CC.R1 with subgroup A ASV. No infected CC.R1 chicken produced detectable sarcoma (Table 1), confirming the purity of the subgroup A ASV stock because line CC.R1 is resistant to the A subgroup (13) and sensitive to the B, C, and D subgroups (35).

Table 1.

Incidence and growth of tumors induced by subgroup A and B ASVs

| Chicken line | ASV subgroup | Tumor incidencea | Mean tumor wt (g) on p.i. days: |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21–28 | 29–34 | 35–42 | |||

| CC.R1 | A | 0/5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| P | A | 6/8b | —c | — | 31.8 (n = 4) |

| P | B | 8/8d | 56.25 (n = 6) | — | 152.4 (n = 1) |

Data represent number of chicks with tumors/total number of chicks tested.

Two tumors regressed in this group.

—, the weight of tumors was not measured at that time interval.

One chick with a tumor died prematurely of nonspecific causes.

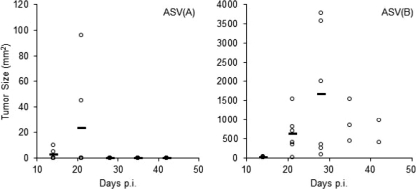

In a subsequent experiment, we compared the kinetics of tumor growth over time by noninvasive estimation of tumor size. Again, line P was fully susceptible to sarcoma induction by subgroup B ASV. In a cohort of six chicks, all birds developed sarcomas within 14 days p.i., and the sarcomas grew progressively in all but one chick, so that three birds were terminated by day 28 and one was terminated by day 35 p.i. (Fig. 2). In contrast, subgroup A ASV induced slowly growing sarcomas in just two birds on day 14, and these tumors completely disappeared by day 28 p.i. The remaining four birds did not develop detectable sarcomas even after 42 days p.i. (Fig. 2). Taken together, the in vivo tumor growth corresponds with the spread of the virus in vitro and confirms the decreased susceptibility of line P to subgroup A ASLV.

Fig 2.

Growth of sarcomas induced after infection with 100 FFU of ASV in line P 10-day-old chicks. Tumor sizes (mm2) induced in chicks infected with ASV(A) (left) or ASV(B) (right) were measured on the days indicated. The tumor size in each bird is indicated by an individual dot, with the average tumor size for the group shown with a horizontal bar. Note the different y-axis scales. Only two tumors were induced by ASV(A); the results for the remaining four chicks without tumors overlap on the x axis. Only three and two chicks survived on days 35 and 42, respectively; the rest of the chicks were sacrificed before they reached the terminal stage.

Identification of new tvar3 and tvar4 alleles with affected splicing of the first intron.

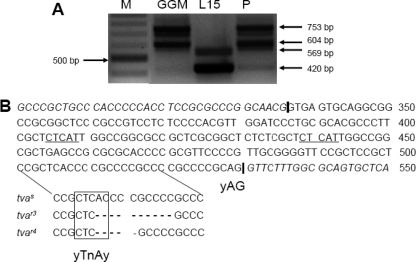

In order to characterize the molecular defects accounting for the decreased sensitivity to subgroup A ASLV in line P and G. g. murghi, we amplified the whole tva coding sequence from line P and G. g. murghi CEFs and from L15 CEFs as a control by RT-PCR using the primers complementary to the 5′ end of the coding sequence and 3′ untranslated regions. Whereas the cDNA products from L15 CEFs were of the expected sizes corresponding to the shorter and longer tva forms (13), the products from line P were longer by ca. 200 bp (Fig. 3A), suggesting retention of the first intron, i.e., nucleotides 337 to 530, according to the numbering by Elleder et al. (13). We therefore amplified and sequenced the genomic tva DNA from line P CEFs using primers localized in the 5′ end of the coding sequence and in the second exon. The sequence revealed a 10-nucleotide deletion within the first tva intron, either the sequence CACCCCGCCC, nucleotides 506 to 515, or the sequence ACCCCGCCC, nucleotides 507 to 516 (Fig. 3B). In any case, this deletion comprises the A, nucleotide 507, of the CTCAC, the consensus sequence of the branch-point signal (16). Because this putative branch-point signal is in optimal distance from the intron-exon boundary, we suggest that it is used in splicing out the first intron from the tva mRNA and its deletion abrogates the splicing. Retention of the first intron changes the translational reading frame of both forms of the tva mRNAs immediately after the end of exon 1 and introduces premature TGA stop codons in exon 4 or 5 of the longer or shorter mRNA, respectively. These nonspliced mRNAs should be translated into proteins of 196 and 177 amino acids, respectively, with only 36 N-terminal amino acids being identical with functional Tva protein. Because two different tva alleles, tvar1 and tvar2, conferring resistance to ASLV subgroup A have already been described (13), we have named this new allele in line P tvar3.

Fig 3.

The tvar3 and tvar4 alleles in chicken line P and G. g. murghi contain deletions in the first intron. (A) PCR amplification of the whole tva coding sequence from G. g. murghi (GGM), L15, and line P CEFs. Two forms of normal tva transcripts in L15 420 bp and 569 bp in length and two forms with retained intron 1 in G. g. murghi and line P 604 bp and 753 bp in length are shown. Lane M, DNA marker 100-bp ladder. (B) Partial sequence of the chicken tva intron 1 and junctions with exons 1 and 2. The region of the branch point with respective deletions in tvar3 and tvar4 alleles are highlighted below, and deleted bases are indicated with dashes. The deduced branch-point signal is boxed, and the 3′ splice signal (yAG) is indicated. The putative alternative branch-point signals are underlined. The intron-exon junctions are indicated by vertical bars; exon sequences are in italics.

Based on this finding, we analyzed the same intronic region of tva in G. g. murghi. The same 5′ part of genomic tva DNA was amplified and sequenced from four CEF cultures prepared individually from four G. g. murghi embryos. In two G. g. murghi embryos, we found the same 10-nucleotide deletion previously identified in line P. In the remaining two G. g. murghi embryos, we identified a new type of intronic deletion abrogating the putative branch-point signal. Instead of the deleted ACCCCGCCCC sequence, there was deletion of a pentanucleotide, ACCCC, nucleotides 507 to 511 (Fig. 3B). We have denoted this allele tvar4. Although different in sequence, both tvar3 and tvar4 lack the putative branch-point signal of intron 1, which could be the cause of defective splicing and decreased susceptibility to subgroup A ASLV in line P and G. g. murghi. In contrast to tvar3, the tvar4 allele should retain the intronic sequence of 189 nucleotides, which means that the 40-amino-acid LDLR homologous cysteine-rich sequence encoded by exon 2 would be translated in a correct frame. The receptor function of the Tvar4 product is obviously hampered by the presence of a 63-amino-acid stretch immediately upstream of the cysteine-rich sequence.

In order to confirm the retention of intron 1 in tvar3 and tvar4 transcripts, we amplified the whole tva coding sequence using the primers complementary to the 5′ end of the coding sequence and 3′ untranslated region from cDNA of individually prepared line P and G. g. murghi CEFs and sequenced the 753-bp RT-PCR products. We obtained the correct tva sequences with retained intron 1 in all cases analyzed. We observed a 10-nucleotide deletion corresponding to the tvar3 allele in two G. g. murghi embryos and a 5-nucleotide deletion corresponding to the tvar4 allele in two other G. g. murghi embryos. Interestingly, in line P CEFs, we detected not only the tvar3 allele but also, in 2 out of 10 embryos, the tvar4 allele. We thus conclude that both alleles are present in the population of red jungle fowl as well as in the close-bred P line.

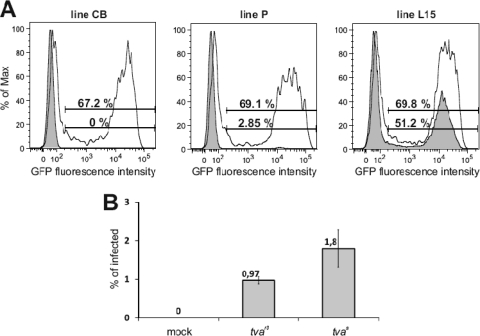

Intronic deletion in the tvar3 allele is responsible for the decreased susceptibility to subgroup A ASLV.

Lines P and L15 are genetically unrelated, and we can assume that they differ in multiple loci, in addition to the two tva alleles. To exclude the effect of different genetic backgrounds on the susceptibility to subgroup A ASLV, we cloned tvas and tvar3 alleles and reproduced their effects in overexpression experiments. First, we overexpressed the tvas allele cloned from the fully susceptible line L15 in CEFs of the CB, P, and L15 lines and estimated the susceptibility to subgroup A ASLV. CEFs of the inbred line CB, which are resistant to the subgroup A ASLV because of a C40W substitution in its tvar1 allele (13), become susceptible after overexpression of tvas, as evidenced by 67% of infected GFP-positive cells at 2 days postinfection (Fig. 4A, left). Even in the susceptible L15 line, tvas overexpression increases the percentage of infected GFP-positive cells (Fig. 4A, right). Similarly, for CEFs of line P, the susceptibility increases from 2.85% to 69.1% of infected cells (Fig. 4A, middle). This clearly shows that complementation of the tva defect alone confers full susceptibility to the subgroup A ASLV.

Fig 4.

Expression of the cloned tvas and tvar3 confers susceptibility to the subgroup A ASLV. (A) CEFs of the CB (left), P (middle), and L15 (right) lines were transfected with a tvas expression vector, infected at a multiplicity of infection of 1 with RCASBP(A)GFP at 1 day p.t., and analyzed by FACS at 2 days postinfection as a mean of three parallel dishes. Open curves of FACS histograms represent cells transfected with tvas; shaded curves represent mock-transfected cells. The relative fluorescence is plotted against the cell count, and the percentages of GFP-positive tvas-transfected cells (top) and GFP-positive mock-transfected cells (bottom) are given. (B) CEFs of the CB line transfected with a low dose of either tvas and tvar3, i.e., 0.02 μg of either pVITROtdTomato-tvaL15 or pVITROtdTomato-tvaP plasmids per 5 × 104 cells in a 3.8-cm2 well, infected at a multiplicity of infection of 1 with RCASBP(A)GFP at 1 day p.t., and analyzed by FACS at 2 days postinfection. Percentages of GFP-positive cells from FACS are shown as means and standard deviations from two parallel dishes.

In order to reproduce the decreased efficiency of subgroup A ASLV infection in an independent genetic background, we transfected the resistant CB CEFs with low doses of cloned tvas and tvar3 alleles and compared the resulting susceptibility to the virus. We observed roughly 2-fold higher infectivity in the cells expressing tvas than in the cells transfected with tvar3 (Fig. 4B), which confirms again that the molecular defect found in the tvar3 allele is the cause of decreased susceptibility observed in line P. It is of note that the difference in susceptibility to subgroup A ASLV in CB CEFs expressing tvas and tvar3 was obtained after transfection of low doses of plasmid DNA, i.e., 0.02 μg per 5 × 104 cells in a 3.8-cm2 well. Transfection of 0.2 μg led to a less striking difference, and transfection of 2 μg did not exhibit any significant difference at all (data not shown). Therefore, overexpression of tvar3 transcripts from the transfected construct leads to the display of at least a small amount of functioning Tva receptor molecules. Highly effective virus entry together with sensitive detection of virus infection in the GFP-based RCAS system can thus elicit only weak differences between the tvas and tvar3 alleles.

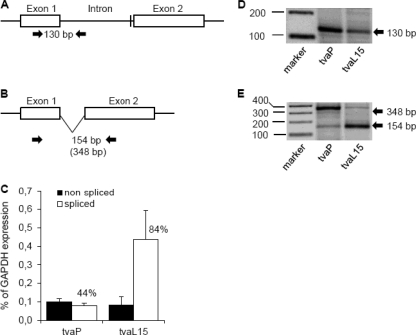

Quantitative analysis of tvar3 splicing.

Complete abrogation of intron 1 splicing from the tvar3 mRNA due to the deletion of a likely branch-point signal does not correspond with the weak residual susceptibility of line P and G. g. murghi to subgroup A ASLV observed in vitro and in vivo. We therefore suggest that an alternative, probably suboptimal intronic sequence could replace the branch-point signal so that at least a small part of tvar3 transcripts can be correctly spliced. In fact, faint bands of amplified normal short and long tva cDNAs, 420 and 569 bp, are visible together with the major bands amplified in line P (Fig. 3A). There are several intronic sequences upstream of the 10-nucleotide deletion, e.g., CTCAT, nucleotides 405 to 409 and 439 to 443, that could serve as an alternative branch-point signal.

In order to analyze the splicing efficiency, we quantified the transcripts with spliced and nonspliced intron 1 in P and L15 chicken lines using the splice-specific qRT-PCR technique (39). Transcripts with nonspliced intron 1 were detected as a PCR product amplified with primers in exon 1 and intron 1 (Fig. 5A), and the spliced transcripts were detected using primers spanning exon 1 and exon 2 (Fig. 5B). In three independent experiments, the mean level of spliced tvar3 reached 44% of the total tvar3 transcript in P line CEFs, whereas the tvas allele produced 84% of the spliced transcripts in L15 CEFs. The total endogenous tva transcription was rather low in these experiments and varied between 0.2% and 0.6% of GAPDH expression in P line CEFs and L15 line CEFs, respectively (Fig. 5C). Under these conditions, the percentages of spliced tvar3 transcripts could have been overestimated because the short intron 1 can be read through from primers spanning exons 1 and 2. The presence of a longer read-through transcript in the PCR product of the spliced tva is shown in Fig. 5E. In any case, we have demonstrated that the 10-nucleotide deletion of the branch-point signal strongly decreased but did not completely abrogate the splicing of the first tva intron, which explains the decreased susceptibility of line P to the subgroup A ASLVs.

Fig 5.

Transcription and splicing of the tvar3 allele in line P and wild-type tvas allele in the L15 line. Schematic representation of intron 1 retention (A) and splicing (B), together with positions of primers for the splice-specific PCR (arrows) and the sizes of diagnostic PCR products. The position of the intronic deletion is denoted by a vertical bar. (C) The levels of nonspliced (black columns) and spliced (open columns) transcripts of the tvar3 allele in line P and tvas allele in line L15 were estimated by qRT-PCR and are shown as the average percentage of the GAPDH expression ± SD from three triplicates. (D) The molecular sizes of the RT-PCR products of nonspliced tva mRNA are shown. Lane 1, marker of molecular size (indicated on the left, in base pairs); lane 2, nonspliced tvar3 mRNA, RT positive; lane 3, nonspliced tvas mRNA, RT positive. (E) The molecular sizes of the RT-PCR product of spliced tva mRNA are shown. Lane 1, marker of molecular size; lane 2, spliced tvar3 mRNA, RT positive; lane 3, spliced tvas mRNA, RT positive.

Different display of Tva on the surface of cells with normal and decreased susceptibility to subgroup A ASLV.

Retention of the tvar3 intron should lead to transcripts with decreased stability, affected mRNA transport, and inefficient translation of soluble product without any affinity for virus glycoproteins. Thus, the decreased efficiency of tvar3 splicing should be accompanied by a changed display of functional Tva receptor on the cells of line P. We compared the presence of the Tva receptor on CEFs of line P and fully susceptible line L15 using soluble immunoadhesin SU(A)-rIgG, which combines the receptor-binding parts of the subgroup A SU glycoprotein with the IgG heavy chain. We observed that SU(A)-rIgG specifically bound to L15 cells, whereas the relative cell surface level of Tva was the same in CEFs of line P and negative-control line CB (Fig. 6). This confirms the tvar3 expression defect at the protein level, and we suggest that the combination of very low endogenous tva transcription (Fig. 5C) with inefficient splicing decreases the receptor expression to the background level. On the other hand, virus entry is highly efficient, at least for the transmembrane form of Tva (17), and can occur in cells with extremely small amounts of Tva that are undetectable using the SU(A)-rIgG immunoadhesin.

Fig 6.

Comparison of the Tva display on the surface of CEFs from CB, L15, and P chicken lines. Cells were incubated with crude extracellular supernatants containing the SU(A)-rIgG immunoadhesin and with goat-anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488. The relative fluorescence is plotted against the cell count: open bold peak, L15 CEFs; overlapping open thin and shaded peaks, CB and P CEFs, respectively.

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of ASLV in chicken populations might have imposed strong selection pressure toward resistance or at least decreased susceptibility to ASLV infection. Little is known about the infestation and in vivo pathogenicity of ASLV in wild jungle fowl. We can, however, infer from domestic chickens that natural ASLV infection has a substantial negative impact on the health, fitness, reproduction, and life span of free-ranging poultry. Under these conditions, we can expect a wide prevalence of resistance alleles in loci encoding the receptors for ASLVs. In fact, only the tvbs3 allele conferring the full resistance to subgroup E ALSV is present in most lines of domestic chickens, which correlates with the exposure to endogenous ASLVs and selective advantage provided to homozygous tvbs3 carriers (1, 3). The C62S substitution in the TvbS3 product of this allele can cause severe structural alterations; nevertheless, it does not abrogate the ability to bind subgroup B and D ASLVs.

The remaining resistance alleles in tva, tvb, and tvc loci were found in particular inbred lines of chickens, and the resistance is caused by premature termination codons, frameshift mutations, and substitution of critical cysteine residues (13, 14, 25). Such alleles definitely cannot code for any product carrying out the normal cellular functions, but we do not know what their natural ligands are or what their detrimental impact on either homozygous or heterozygous chickens is. These proteins are not absolutely vital, and no striking phenotype was observed in inbred chicken lines established decades ago and kept in captivity under artificial conditions. We, however, admit that the absence of these receptor proteins can harm feral chickens and impose a selection pressure in favor of the wild-type alleles. Provided such counterselection and rapid evolution of retrovirus envelope glycoproteins, we assume that complete resistance to ASLV entry can appear but cannot prevail and be fixed in the population. We suggest that mutations with modest effects on both virus entry and natural receptor functions represent the pool of genetic variability required for ASLV-chicken coevolution. As an example, we can cite our previous identification of the tvbr2 allele with a single-amino-acid substitution and decreased susceptibility to subgroups B and D and complete resistance to subgroup E (35). The subgroup J ALV receptor was identified to be Na+/H+ exchanger type 1 (10), a housekeeping protein widely expressed in multiple cell types. Accordingly, all chicken lines analyzed so far are susceptible to ALV subgroup J (32), and we expect stronger counterselection of the resistance alleles.

In the present work, we identified two new tva alleles with reduced susceptibility to subgroup A ASLV due to intronic deletions of the branch point that affect the splicing and decrease the display of the Tva receptor on the cell surface. Both tvar3 and tvar4 might be quite prevalent in chickens, as was detected in one close-bred line as well as in a subspecies of the red jungle fowl. We have also shown a new molecular mechanism leading to the decreased susceptibility to virus entry. Thus, our work points to the importance of analyzing not only the coding sequences but also the introns and 5′ and 3′ UTRs of the receptor genes. Intronic deletion has already been shown in the mouse Cecam1 gene encoding a receptor for multiple pathogens, including mouse hepatitis virus. A short deletion in the first intron was found, and the changed pattern of splice variants was described here (7). The same or similar effects could also be exerted by epigenetic changes of the receptor gene expression, which might decrease the display of functional receptors on the cell surface. This was demonstrated in the case of the Pit2 receptor for murine amphotropic leukemia virus and gibbon ape leukemia virus in CHO cells and the FLVCR receptor for feline leukemia virus subgroup C in Mus dunni cells (37).

Alterations of splicing caused by point mutations or deletions in both splice sites and auxiliary cis-regulatory elements are more prevalent than thought previously. The mechanism of mRNA splicing is highly complex, requiring multiple interactions between pre-mRNA, small nuclear ribonucleoproteins, and splicing factor proteins. Regulation of this process is even more complicated, relying on loosely defined cis-acting regulatory sequence elements, trans-acting protein factors, and epigenetic marks of DNA and histones. Many different human diseases can be caused by errors in mRNA splicing or its regulation. Interestingly, intronic deletions causing exon skipping or intron retention in the human LDLR gene were identified in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia (4, 9, 12, 22, 40). Because the human LDLR gene is homologous to the chicken tva gene, it is tempting to speculate that this is a common mechanism of mutagenesis within this gene family.

Quantitative analysis of tvar3 splicing detected a high prevalence of the nonspliced over the spliced transcript (Fig. 4C). The actual display of translated Tvar3 product on the surface of P line CEFs was shown to be at the level of the resistant CB line (Fig. 6), which could be explained by nonsense-mediated mRNA decay of the tvar3 transcript with retained intron 1 (reviewed in reference 27). This kind of mRNA decay generally requires that translation terminate sufficiently upstream of an exon-exon junction (29, 30), and the premature stop codon in the longer transcript positioned 76 nucleotides upstream of the exon 4-exon 5 junction can be a proper target. Sometimes, in retroviral full-length transcripts, the stop codon can be masked by highly structured stability elements (42). On the other hand, the presence of a low level of nonspliced tvas mRNA (Fig. 5C) could indicate some leakage of the tva splicing process. In any case, weak splicing of tvar3 and tvar4 alleles occurs, and putative alternative branch-point signals must be employed. The low efficiency of the alternative branch-point signal in the tvar3 and tvar4 alleles can be explained by either the nucleotide sequence or the distance to the 3′ splicing signal. The sequence of the branch-point signal is quite variable, with the exception of the fixed T and A positions of the yTnAy consensus determined both experimentally (16) and bioinformatically (11) in the human genome. From this point of view, two CTCAT sequences, nt 405 to 409 or 439 to 443, could serve as optimal alternative branch-point signals. However, their position relative to the 3′ splice signal is far from the usual 21 to 34 nucleotides upstream of the 3′ end of the intron. In a representative set of introns with multiple potential branch-point signals, the most downstream signals were four to eight times more frequently employed than their upstream counterparts (16). Furthermore, alignment of the branch-point signal with a downstream polypyrimidine tract is crucial for branch-point recognition. These rules weaken in a gradual manner as intron length increases, and the distance between the branch-point signal and 3′ splicing signal positively correlates with alternative splicing. Skipped exons tend to be preceded by introns containing distant branch-point signals rather than constitutive exons (11), which might be the case for tva intron 3. Altogether, the branch-point signal deletion in the first intron of tvar3 and tvar4 can be compensated by upstream alternative branch-point signals; however, these are suboptimal and do not ensure efficient splicing. Lariat RT-PCR could identify the currently used branch point.

There are few examples of retrovirus receptor mutations inducing resistance or decreased susceptibility to virus entry in populations of wild animals. As a parallel to the chicken tvbr3 and tvbr4 alleles, restrictive variants of XPR1, the receptor for xenotropic and polytropic mouse leukemia viruses, evolved in wild mouse species carrying endogenous variants of respective infectious viruses (44, 46). Furthermore, six naturally occurring XPR1 alleles with distinct host ranges and specific amino acid substitutions in two extracellular loops of the receptor have been described (45). On the other hand, the discovery of a mutant allele of the CCR5 receptor gene bearing a 32-bp deletion and preventing infection with M-tropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (26) was not matched with the finding of restrictive coreceptor variants in apes or monkeys (43), despite the pathogenic outcome of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection in chimpanzees (24). Epigenetic mechanisms might play a role in SIV-infected sooty mangabeys, where low expression of CCR5 prevents virus infection of CD4+ central memory T cells and the animals avoid AIDS, despite continuous virus replication (31).

Our analysis addresses two important points of virus-host coevolution: (i) how polymorphisms in receptor genes help in adaptation of natural populations to exposure to pathogenic retroviruses and (ii) what type of receptor mutations represents the outcome of antagonistic interactions between the host and the retrovirus. Further investigation of all tv loci in other chicken lines and outbred populations would help in understanding the evolutionary mechanisms driving the development of host resistance to retroviral infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Czech Science Foundation, grant no. P502/10/1651, and the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, institutional concept no. AV0Z50529514.

We are grateful to Jitka Králíčková and Ivan Kubát from the Zoo Ohrada u Hluboké for providing us with embryonated eggs of red jungle fowl and to Mark J. Federspiel (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN) for the construct encoding the SU(A)-rIgG immunoadhesin.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 14 December 2011

REFERENCES

- 1. Adkins HB, Blacklow SC, Young JAT. 2001. Two functionally distinct forms of a retroviral receptor explain the nonreciprocal receptor interference among subgroup B, D, and E avian leukosis viruses. J. Virol. 75:3520–3526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Adkins HB, et al. 1997. Identification of a cellular receptor for subgroup E avian leukosis virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94:11617–11622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Adkins HB, Brojatsch J, Young JAT. 2000. Identification and characterization of a shared TNFR-related receptor for subgroup B, D, and E avian leukosis viruses reveal cysteine residues required specifically for subgroup E viral entry. J. Virol. 74:3572–3578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Amsellem S, et al. 2002. Intronic mutations outside of Alu-repeat-rich domains of the LDL receptor gene are a cause of familial hypercholesterolemia. Hum. Genet. 111:501–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barnard RJO, Elleder D, Young JAT. 2006. Avian sarcoma and leukosis virus-receptor interactions: from classical genetics to novel insights into virus-cell membrane vision. Virology 344:25–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bates P, Young JA, Varmus HE. 1993. A receptor for subgroup A Rous sarcoma virus is related to the low density lipoprotein receptor. Cell 74:1043–1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Blau DM, et al. 2001. Targeted disruption of the Ceacam1 (MHVR) gene leads to reduced susceptibility of mice to mouse hepatitis virus infection. J. Virol. 75:8173–8186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brojatsch J, Naughton J, Rolls MM, Zingler K, Young JA. 1996. CAR1, a TNFR-related protein, is a cellular receptor for cytopathic avian leukosis-sarcoma viruses and mediates apoptosis. Cell 87:845–855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cameron J, Holla ØL, Kulseth MA, Leren TP, Berge KE. 2009. Splice-site mutation c.313+1, G>A in intron 3 of the LDL receptor gene results in transcripts with skipping of exon 3 and inclusion of intron 3. Clin. Chim. Acta 403:131–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chai N, Bates P. 2006. Na+/H+ exchanger type 1 is a receptor for pathogenic subgroup J avian leukosis virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:5531–5536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Corvelo A, Hallegger M, Smith CWJ, Eyras E. 2010. Genome-wide association between branch point properties and alternative splicing. PLoS Comput. Biol. 6:e1001016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Defesche JC, et al. 2008. Silent exonic mutations in the low-density lipoprotein receptor gene that cause familial hypercholesterolaemia by affecting mRNA splicing. Clin. Genet. 73:573–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Elleder D, Melder DC, Trejbalova K, Svoboda J, Federspiel MJ. 2004. Two different molecular defects in the Tva receptor gene explain the resistance of two tvar lines of chickens to infection by subgroup A avian sarcoma and leukosis viruses. J. Virol. 78:13489–13500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Elleder D, et al. 2005. The receptor for the subgroup C avian sarcoma and leukosis viruses, Tvc, is related to mammalian butyrophilins, members of the immunoglobulin superfamily. J. Virol. 79:10408–10419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Federspiel MJ, Hughes SH. 1997. Retroviral gene delivery. Methods Cell Biol. 52:167–177 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gao K, Masuda A, Matsuura T, Ohno K. 2008. Human branch point consensus sequence is yUnAy. Nucleic Acids Res. 36:2257–2267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gray ER, Illingworth CJR, Coffin JM, Stoye JP. 2011. Binding of more than one Tva800 molecule is required for ASLV-A-entry. Retrovirology 8:e96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gudkov AV, Obukh IB, Serov SM, Naroditsky BS. 1981. Variety of endogenous proviruses in the genomes of chickens of different breeds. J. Gen. Virol. 57:85–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Himly M, Foster DN, Bottoli I, Iacovoni JS, Vogt PK. 1998. The DF-1 chicken fibroblast cell line: transformation induced by diverse oncogenes and cell death resulting from infection by avian leukosis viruses. Virology 248:295–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Holmen SL, Federspiel MJ. 2000. Selection of a subgroup A avian leukosis virus [ALV(A)] envelope resistant to soluble ALV(A) surface glycoprotein. Virology 273:364–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hughes SH. 2004. The RCAS vector system. Folia Biol. (Praha) 50:107–119 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jelassi A, et al. 2008. A novel splice site mutation of the LDL receptor gene in a Tunisian hypercholesterolemic family. Clin. Chim. Acta 392:25–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kanginakudru S, Metta M, Jakati RD, Nagaraju J. 2008. Genetic evidence from Indian red jungle fowl corroborates multiple domestication of modern day chicken. BMC Evol. Biol. 8:e174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Keele BF, et al. 2009. Increased mortality and AIDS-like immunopathology in wild chimpanzees infected with SIVcpz. Nature 460:515–519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Klucking S, Adkins HB, Young JAT. 2002. Resistance to infection by subgroups B, D, and E avian sarcoma and leukosis viruses is explained by a premature stop codon within a resistance allele of the tvb receptor gene. J. Virol. 76:7918–7921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liu R, et al. 1996. Homozygous defect in HIV-1 coreceptor accounts for resistance of some multiply-exposed individuals to HIV-1 infection. Cell 86:367–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Melder DC, Pankratz VS, Federspiel MJ. 2003. Evolutionary pressure of a receptor competitor selects different subgroup A avian leukosis virus escape variants with altered receptor interactions. J. Virol. 77:10504–10514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Murphy HM. 1977. A new, replication-defective variant of the Bryan high-titer strain Rous sarcoma virus. Virology 77:705–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nagy E, Maquat LE. 1998. A rule for termination-codon position within intron-containing genes: when nonsense affects RNA abundance. Trends Biochem. Sci. 23:198–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nicholson P, Mühlemann O. 2010. Cutting the nonsense: the degradation of PTC-containing mRNAs. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 36:1615–1620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Paiardini M, et al. 2011. Low levels of SIV infection in sooty mangabey central memory CD4(+) T cells are associated with limited CCR5 expression. Nature Med. 17:830–836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Payne LN, et al. 1991. A novel subgroup of exogenous avian leukosis virus in chickens. J. Gen. Virol. 72:801–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Plachý J. 2000. The chicken—a laboratory animal of the class Aves. Folia Biol. (Praha) 46:17–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rainey GJA, Natonson A, Maxfield LF, Coffin JM. 2003. Mechanisms of avian retroviral host range extension. J. Virol. 77:6709–6719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Reinišová M, et al. 2008. A single-amino-acid substitution in the TvbS1 receptor results in decreased susceptibility to infection by avian sarcoma and leukosis virus subgroups B and D and resistance to infection by subgroup E in vitro and in vivo. J. Virol. 82:2097–2105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Svoboda J, et al. 1992. Tumor induction by the LTR, v-src, LTR DNA in four B (MHC) congenic lines of chicken. Immunogenetics 35:309–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tailor CS, Nouri A, Kabat D. 2000. Cellular and species resistance to murine amphotropic, gibbon ape, and feline subgroup C leukemia viruses is strongly influenced by receptor expression levels and by receptor masking mechanisms. J. Virol. 74:9797–9801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Taplitz RA, Coffin JM. 1997. Selection of an avian retrovirus mutant with extended receptor usage. J. Virol. 71:7814–7819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Trejbalová K, et al. 2011. Epigenetic regulation of transcription and splicing of syncytins, fusogenic glycoproteins of retroviral origin. Nucleic Acids Res. 39:8728–8739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Webb JC, Patel DD, Shoulders CC, Knight BL, Soutar AK. 1996. Genetic variation at a splicing branch point in intron 9 of the low density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor gene: a rare mutation that disrupts mRNA splicing in a patient with familial hypercholesterolaemia and a common polymorphism. Hum. Mol. Genet. 5:1325–1331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Weiss RA. 1992. Cellular receptors and viral glycoproteins involved in retrovirus entry, p 1–108 In Levy JA. (ed), Retroviridae, vol 2. Plenum Press, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 42. Withers JB, Beemon KL. 2010. Structural features in the Rous sarcoma virus RNA stability element are necessary for sensing the correct termination codon. Retrovirology 7:e65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wooding S, et al. 2005. Contrasting effects of natural selection on human and chimpanzee CC chemokine receptor 5. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 76:291–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yan Y, Knoper RC, Kozak CA. 2007. Wild mouse variants of envelope genes of xenotropic/polytropic mouse gammaretroviruses and their XPR1 receptors elucidate receptor determinants of virus entry. J. Virol. 81:10550–10557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yan Y, Liu Q, Kozak CA. 2009. Six host range variants of the xenotropic/polytropic gammaretroviruses define determinants for entry in the XPR1 cell surface receptor. Retrovirology 6:e87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yan Y, et al. 2010. Evolution of functional and sequence variants of the mammalian XPR1 receptor for mouse xenotropic gammaretroviruses and the human-derived XMRV. J. Virol. 84:11970–11980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Young JAT. 2001. Virus entry and uncoating, p 87–103 In Knipe DM, Howley P. (ed), Fields virology, vol 2. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 48. Young JAT, Bates P, Varmus HE. 1993. Isolation of a chicken gene that confers susceptibility to infection by subgroup A avian leukosis and sarcoma viruses. J. Virol. 67:1811–1816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zingler K, Young JA. 1996. Residue Trp-48 of Tva is critical for viral entry but not for high-affinity binding to the SU glycoprotein of subgroup A avian leukosis and sarcoma viruses. J. Virol. 70:7510–7516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]