Abstract

Background

Psychotherapies with known efficacy in adolescent depression have been adapted for prepubertal children; however, none have been empirically validated for use with depressed very young children. Due to the centrality of the parent-child relationship to the emotional well being of the young child, with caregiver support shown to mediate the risk for depression severity, we created an Emotional Development (ED) module to address emotion development impairments identified in preschool onset depression. The new module was integrated with an established intervention for preschool disruptive disorders, Parent Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT). Preliminary findings of an open trial of this novel intervention, PCIT-ED, with depressed preschool children are reported.

Methods

PCIT was adapted for the treatment of preschool depression by incorporating a novel emotional development module focused on teaching the parent to facilitate the child’s emotional development and enhance emotion regulation. Eight parent-child dyads with depressed preschoolers participated in 14 sessions of treatment. Depression severity, internalizing and externalizing symptoms, functional impairment, and emotion recognition/discrimination were measured pre and post treatment.

Results

Depression severity scores significantly decreased with a large effect size (1.28). Internalizing and externalizing symptoms as well as functional impairment were also significantly decreased pre to post treatment.

Conclusions

PCIT-ED appears to be a promising treatment for preschoolers with depression and the large effect sizes observed in this open trial suggest early intervention may provide a window of opportunity for more effective treatment. A randomized controlled trial of PCIT-ED in preschool depression is currently underway.

MeSH Key Words: Affect, Child, Depressive Disorder/psychology, Depressive Disorder/therapy, Mood Disorders, Mother-child Relations, Behavior Therapy, Humans

Introduction

Despite longstanding public health recognition of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) arising in pre-pubertal children, there have been little data to inform how to treat the disorder in young children. Data characterizing and validating depression in preschool aged children between three and six years of age has recently become available, with prevalence rates very similar to that in school age children, estimated between 1–2%. [1–4] Evidence for a specific and stable symptom constellation, discriminant validity from other early onset mental disorders, and greater family history of affective disorders in depressed preschoolers have been provided.[1,2] Further, biological correlates similar to those known in adult MDD and predictive validity evidenced by homotypic continuity into early school age have also been found.[5,6] Impairment in adaptive functioning rated by parents and teachers has been demonstrated in depressed versus healthy preschoolers, underscoring the clinical significance and need for intervention for preschool MDD. [3] Although MDD is relatively rare in very young children, due to the recurrent and often progressive nature of the disorder, the earliest possible identification and intervention may prove extremely important.

We are unaware of any psychotherapeutic treatments empirically validated for preschool depression. In the largest meta-analysis to date on effects of psychotherapy for depressed children and adolescents, [7] only one study included children as young as seven and no studies included children age six or under. Psychotherapies designed for other mental disorders in preschool children are available, but have not been specifically tested or adapted for preschool depression. For example, Play Therapy is widely used with very young children; however, this approach is generally applied to a range of young child problems and empirical evidence demonstrating efficacy is lacking. [8,9] Other interventions based upon cognitive or behavioral techniques have also been widely used with young children for a variety of internalizing or externalizing problems. For example, Shure and Spivack developed the “I Can Problem Solve” program (formally known as interpersonal cognitive problem solving) for the reduction and prevention of early high-risk behavior, designed primarily for the school setting.[10,11] Other techniques like self-statement modification, self-control training, and problem-solving skills training have also been used successfully with young children, though not much empirical data exists for children under five.[12]

Traditionally, the use of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) with children under the age of eight has been controversial. Recent work has suggested that young children are capable of engaging in cognitive techniques when developmentally appropriate modifications are made.[12,13] For example, several recent studies support the use of adapted CBT for anxiety disorders in children under the age of seven.[14–17] All of these interventions included substantial parental involvement in treatment, developmentally appropriate techniques with concrete examples, and age appropriate stories, games, and activities. To date, these types of CBT interventions have not been adapted for use with preschool children with depression. These findings suggest that novel approaches to the treatment of early childhood depression are needed.

Based on the promising findings from early dyadic interventions in several preschool mental disorders, combined with the need for more effective treatments for childhood depressive disorders overall, we developed an early dyadic intervention for preschool depression. [18–20] The intervention is an adaptation and expansion of Parent Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT), a manualized psychotherapy with established efficacy for the treatment of preschool disruptive disorders. [21] Follow-up studies have demonstrated enduring efficacy from this intervention, up to six years post-treatment. [22] Further, recent adaptations to PCIT have been developed for use with young children with anxiety disorders [18,23] Based on these robust efficacy findings and the feasibility and adaptability, PCIT was used as the basis for developing an early intervention for preschool depression. An adaptation of CBT, the leading psychotherapeutic approach for school age depression in children, was considered. However, several unique elements of the PCIT approach, particularly its central focus on the parent-child relationship, in addition to the impressive empirical database in preschool populations made it the most suitable option for adaptation. In addition to some modification of standard PCIT, a new Emotion Development (ED) module was designed to specifically address the emotion development impairments hypothesized to characterize early onset depression. [24] This report describes these treatment methods and reports on the results of a Phase I open trial of the treatment.

Method and Materials

Treatment Development

PCIT-ED Structure

PCIT-ED includes three modules conducted over 14 sessions. Standard PCIT targets the parent-child relationship using behavioral and play therapy techniques to enhance relationship quality and parent’s ability to set nurturing and effective limits with the child. The key components of PCIT are: Child Directed Interaction (CDI), which focuses on strengthening the parent-child relationship by teaching positive play techniques, and Parent Directed Interaction (PDI), which aims to decrease disruptive behavior by teaching the parent to give effective commands and training the parent in methods for handling noncompliance. The CDI and PDI modules are utilized in PCIT-ED, but limited to six sessions in contrast to standard PCIT where they are continued until proficiency is achieved. Didactic sessions devoted to parent teaching are followed by in vivo coaching of the parent using a “bug in the ear” during interactions with the child. This model ensures that parents learn broad classes of behavioral antecedents and response behaviors that can be uniquely tailored to each parent’s ability level and specific child behavioral concerns. [25] The ultimate goal of coaching sessions is to shape both parent and child behaviors to resemble positive parent-child attachment and collaborative social functioning. [18]

The Novel Emotion Development Module

These basic teach and coach PCIT techniques have also been applied to the novel ED module which focuses on teaching the parent to facilitate the child’s emotional development and enhance the child’s capacity for emotion regulation. The goal of the ED module is to enhance the child’s emotional competence by increasing their ability to identify, understand, label and effectively regulate their own emotions. This approach is based on an emotional developmental model of early mood disorders in which the capacity to experience and manage a broad range of emotions is deemed central to healthy development and adaptive function. [21] The first sessions in this phase are designed to position the dyad to maximally benefit from the strategies taught in this module. For example, one session teaches the parent and child relaxation techniques that the child can use to better manage intense emotions. Another “parent only” session addresses issues that may thwart the parent’s ability to assist their child in regulating emotions based on their own personal history of emotion expression and cognitions and feelings related to their child’s expression of emotion. This session builds on the concept of “ghosts in the nursery” in which past experiences of negative relationships interferes with the parent’s ability to accurately see and respond to the child’s emotional needs. [26] During the ED phase, parents are taught skills believed to be important to their role of assisting their child in effectively recognizing and managing emotions. Recognizing the child’s ‘triggers’, assisting the child in labeling the ‘trigger’/emotion/behavior, using a calm voice, maintaining their own emotional balance, and coaching the child in use of relaxation techniques are some of these skills. Because it is important for the child to express and experience emotions to appropriately regulate them; the parent is taught to tolerate the child’s expression of negative emotion rather than immediately extinguishing it (a common parental response to a child’s expression of negative emotion). Following the teaching session, the parent and child participate in ED coaching sessions in which the target emotion is elicited during the session, providing an opportunity for the parent to assist the child in regulating an intense and difficult emotion with active coaching from the therapist. These techniques are designed to enhance the caregiver’s ability to empathize with/become attuned to the child and serve as a more effective teacher and external regulator of the child’s emotional response.

Parents are encouraged to use CDI, PDI, and ED skills at home between sessions and specific “homework” is part of all three modules of treatment. All adaptations to PCIT, including the novel ED module, were reviewed by Sheila Eyberg, Ph.D., the developer of PCIT, to ensure compatibility with the core components of standard PCIT. Therapy was provided by three clinicians (two Master’s level and one D.O.). Therapists’ adherence to the treatment manual was monitored using the Treatment Integrity Checklists (TIC). [27] The TIC is customized for each session to account for elements in that session covered by the therapist. A co-therapist observed each session through a two-way mirror and completed the checklist in-vivo. All treatment sessions were videotaped and viewed by the Principal Investigator (JL) and discussed in weekly case conferences.

Phase I Pilot Study

Participants and Procedures

All study procedures were approved by the Washington University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board. Participants were referred to the study through primary care, mental health, and preschool settings using the Preschool Feeling Checklist (PFC), a validated screening checklist completed by caregivers with established sensitivity for capturing preschool MDD. [28] Primary caregivers of preschoolers who scored > 3 on the checklist were invited to participate in a phone interview in which the Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA) [29] MDD module was administered and demographic data was collected to assess for any exclusions. Caregiver responses to the PAPA were entered into a computer algorithm to determine the presence or absence of MDD.

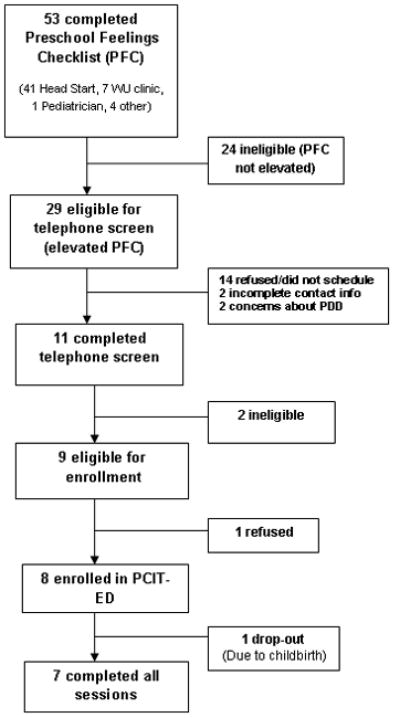

See figure 1 for an illustration of recruitment and study flow. As shown in the figure, eight families met entry criteria and enrolled in the study. Two participants had received treatment prior to the study (one had psychotherapy; one was taking Ritalin, though not consistently). The children were not permitted to continue other forms of psychotherapy during the trial. Children on psychoactive medication (i.e. stimulants) were allowed to continue medication management with their medical provider as long as the dose was not changed during the course of the study.

Figure 1.

Recruitment and Study Flow.

Informed written consent was obtained from caregivers prior to participation. As the minor participants in this study were of an age in which written assent is inappropriate, during consenting the parent interviewer described to the child, in age appropriate language, the procedure for pre and post assessments and the procedure and purpose of the therapy. A comprehensive pre-treatment assessment with parent and child was conducted prior to initiation of treatment and within two weeks of treatment conclusion.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria included: 1) between age 3 years 0 months and 5 years 11 months, 2) research diagnostic criteria for Major Depression (defined by meeting all DSM-IV symptom criteria and setting aside the 2 week duration criterion), 3) living with primary caregiver > 6 months. Potential participants were excluded if they 1) had any major medical or neurologic disease, 2) Pervasive Developmental Disorder, 3) IQ <70, 4) adoption after 12 months of age.

Measures

Clinical outcomes

We used the PAPA, [29] a semi-structured interview designed for preschool children between ages 2 years 0 months through 5 years 11 months with established test re-test reliability and construct validity, [30] to measure the intensity, frequencies, durations, and first onsets of all relevant DSM-IV criteria. We used the Internalizing and Externalizing domains of the Health and Behavior Questionnaire (HBQ), [31] a validated measure of early childhood psychopathology, to obtain ratings of symptoms and adaptive functioning using a Likert scale (0= never or not true, 1= sometimes true, 2= often or very true). The impact of behavioral and emotional problems on family functioning and psychosocial impairment was assessed by the Preschool and Early Childhood Functional Assessment Scale (PECFAS), [32] a semi-structured interview with established concurrent validity and reliability. [33] A sum of 5 domain scores provides an overall functioning score, with scores above 40 indicative of serious emotional disturbance. [33] To measure emotional recognition and competence, we used the 40-item version of the Penn Emotion Differentiation Test (KIDSEDF). [34,35] In the KIDSEDF the child is shown via a computerized self-paced program 40 pairs of faces, one pair at a time, and asked to decide which face expresses the given emotion more intensely. Caregiver acute depressive symptoms were assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory–II, [36] a 21-item measure designed to measure the presence and severity of depressive symptoms.

Treatment feasibility and acceptance

Number of sessions attended and homework compliance were recorded. An independent clinician rated the parent’s participation and engagement in treatment using the Parent Acceptance Inventory (Likert scale rating: 5= strongly agree and 1= strongly disagree). Parent ratings of parental acceptance of treatment, parental observations of improvement, and parental confidence were also measured using a modified version of Therapy Attitude Inventory [37,38] consisting of 15 items (10 original and 5 additional emotion relevant items). This inventory uses Likert scale ratings (5= strong satisfaction and 1 = strong dissatisfaction) yielding total scores ranging from 15 to 75. Parents were given this scale in a take-home packet at the end of each treatment module. They were asked to return the form along with two other self-report measures in a sealed envelope provided.

Data Analysis

We calculated descriptive statistics for each variable and univariate tests for relationships between variables. Wilcoxon Signed Rank tests were computed to test for changes between pre and post assessments. Additionally, we calculated adjusted effect sizes derived from change between pre and post assessments to correct for small sample size. [39] All analyses were performed using The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 17.

Results

Characteristics of Study Sample

Of the eight preschoolers enrolled, five were age five, one was age four, and two were age three. There were four males and four females. Seven children were Caucasian, one was bi-racial (Caucasian/Asian American). Family incomes ranged between $15,000 to over $60,000 per year. Half of the caregivers had graduate/professional degrees (n=4), the remainder had high school or bachelor level education. Six mothers participated in the treatment, one father, and one couple. Seven parents were married or cohabitating, one was divorced. Seven participants completed all 14 sessions of treatment. The eighth participant completed 11 sessions but was unable to continue due to childbirth. We were unable to collect post-treatment assessments for this participant; therefore, the clinical outcomes reported below include the seven participants that completed 14 sessions.

Clinical Outcomes

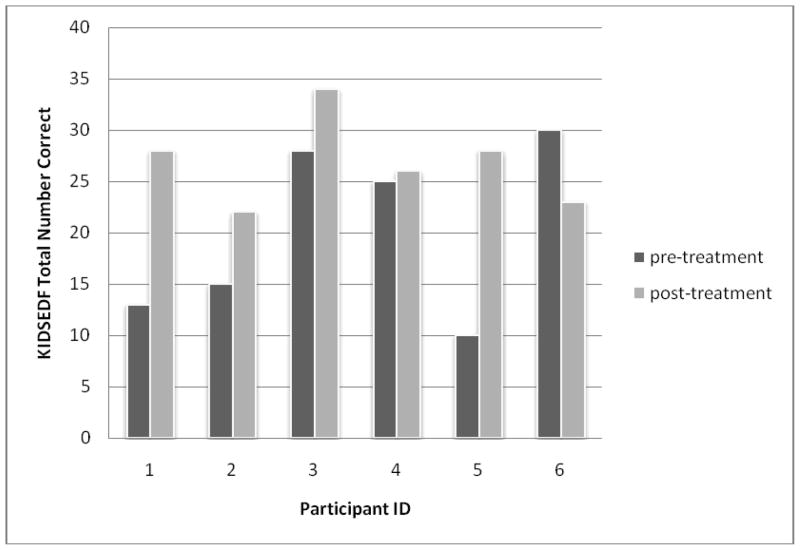

Table 1 shows the results of clinical measures assessed at pre and post treatment. MDD severity scores significantly decreased from pre to post treatment (Effect Size = 1.28). Five of seven preschoolers no longer met criteria for MDD post-treatment. Significant decreases in impairment as measured by the PECFAS were also found (Effect Size = 1.00). Internalizing symptoms and social functioning scores as measured by the HBQ Internalizing domain significantly decreased from pre to post treatment (Effect Size = .88), as well as Externalizing domain symptoms and behavioral problems (Effect Size = .73). Table 2 shows the results from the emotional differentiation task (KIDSEDF). Six preschoolers completed the task pre and post treatment. Most of the preschoolers showed improvements in emotion recognition and discrimination post treatment compared to pre treatment; however, this result was not significant (S= 7.00, p=0.19).

Table 1.

Pre and Post-treatment Scores and Adjusted Effect Sizes for Primary Outcome Measures (n=7).

| Variable | Pre-treatment mean (sd) | Post-treatment mean (sd) | Wilcoxon S | P | ES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAPA MDD Severity | 13.57 (4.39) | 7.57 (6.00) | 2.38 | <0.01 | 1.28 |

| PECFAS | 68.57 (30.78) | 35.71 (27.60) | 2.39 | <0.01 | 1.00 |

| HBQ-Intern | 0.89 (.32) | 0.59 (.27) | 2.37 | <0 .01 | 0.88 |

| HBQ-Extern | 0.94 (0.27) | 0.73 (0.46) | 1.69 | <0.05 | 0.73 |

PAPA MDD: Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment – Major Depressive Disorder module; PECFAS: Preschool and Early Childhood Functional Assessment Scale; HBQ: Health and Behavior Questionnaire – Internalizing and Externalizing subscales

Table 2.

Number of items correct on the Penn Emotion Differentiation Task (KIDSEDF) pre and post-treatment (n=6).

|

NB: Wilcoxon signed rank S=7.00, p=0.19. Removing participant # 6 from the analyses yields Wilcoxon signed rank S= 7.5, p=0.06.

At pre-treatment two caregivers scored in the “moderate” range on the BDI-II and the rest in the “minimal” range. At post-treatment, one parent reported scores in the “mild” range and the rest in the “minimal” range. There were no significant changes in caregiver BDI-II scores pre vs. post treatment. Parental BDI-II scores were not significantly correlated with parent report assessments.

Treatment Feasibility and acceptance

On average it took 18 weeks (± 3.92) to complete all 14 sessions of treatment. Therapists maintained a high degree of manual adherence as rated by the Treatment Integrity Checklist (average 92%, range 82–98%). Parents were moderately compliant with homework each session (average 62% completed, range 42% to 86%). Results from the therapist rated Parent Acceptance Inventory indicated a high level of overall acceptance and engagement in treatment during sessions (mean 4.74 ± 0.10). Scores on the modified Therapy Attitude Inventory indicate parental satisfaction with the treatment (module: CDI mean= 59.4 ± 4.6, range 53–66; PDI mean=55.6 ± 5.97, range 46–65; ED mean=62.5 ± 7.4, range 48–68).

Discussion

There are few proven effective psychotherapeutic treatments for prepubertal depression and none developed for use with preschool children. Therefore, we developed a novel dyadic intervention for preschool depression focused on strengthening the parent-child relationship, building positive interpersonal skills, encouraging prosocial behavior, establishing appropriate limit setting and discipline, and enhancing emotional development and overall emotional competence. This novel emotional development component was designed as the specific early intervention for depression based on a developmental model of depression that hypothesizes alterations in emotion development as a central disease process.[24] This phase I open treatment trial of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy – Emotion Development produced promising results, with large effect sizes specific to depressive symptom reduction in the young child. These effect sizes were similar to those obtained in three other psychosocial intervention studies in older child samples using a pre/post design (mean effect size reported for children ages 6–12 was .73). [40] In this treatment development study, mean depression severity scores decreased by 44% and most children no longer met MDD criteria at the end of treatment. This is further supported by a 48% improvement in functioning as reported by caregivers. These findings suggest that not only did preschoolers show improvements in mood, but also in prosocial behaviors, coping skills, and thought processes. Some of the preschoolers demonstrated improved emotional discrimination on the computerized emotion discrimination task; however small sample size and low power limit our ability to interpret these findings. Finally, we found small but significant changes in maternal reports of children’s externalizing or disruptive behaviors, symptoms which have not been consistently found to respond to depression treatments in older children and adolescents. This is likely due to our use of core PCIT techniques that were designed to directly address these behavior problems. The overall results, although preliminary, suggest that earlier intervention is feasible and perhaps uniquely beneficial for this chronic and relapsing disorder.

We found PCIT-ED to be feasible and acceptable and study families were able to complete treatment within a reasonable time frame. Additionally, the structured manualized approach enabled therapists to adhere to the treatment model to a high degree. Most parents had difficulty completing all of the homework assignments, however. It is unclear what effect this may have had on their ability to acquire skills taught in therapy or on overall treatment outcomes. This should be addressed in future studies. Parents participated actively in treatment sessions as rated by independent clinicians observing the sessions and only one participant was unable to complete treatment (due to childbirth, not treatment dissatisfaction). We found parent reported satisfaction ratings to vary across the different modules of treatment, with the lowest satisfaction reported during the Parent Directed Interaction module. This is not surprising given the intense focus on changing/implementing discipline strategies and the resultant negative responses that are often initially seen from the child. By the end of treatment; however, most parents rated the therapy as highly useful and effective.

Our findings support a dyadic intervention model in which the caregiver-child relationship, rather than the individual child or parenting alone, is the key treatment target, a focus broadly emphasized in other areas of infant/preschool mental health treatment. [20,21] Previous work has shown mother’s infrequent use of supportive care giving strategies based on observation of parenting behavior during dyadic interactions was associated with higher depression severity among preschool children. Additionally, unsupportive parenting was also found to be a robust risk factor for preschool onset depression.[41] Depressed preschoolers and their caregivers also suffered from poorer dyadic relationship quality more globally based on observational measures. [42] These findings underscore the important role of the parent-child relationship quality in the risk and outcomes of preschool depression and potentially in the amelioration of symptoms.[43,44] One potential explanation for the treatment benefits of PCIT-ED is that it targets the quality of the parent-child relationship by enhancing the quality and quantity of parenting support. Further, the novel ED module enhances the parent’s ability to serve as a model and effective external modulator for their preschooler’s developing emotional competence. The therapist utilizes the parent as the “arm of the therapist”, thus changing the parent-child interaction rather than individual behaviors of the child or parent in isolation. [25] The interactive in-vivo coaching during the sessions allows the treatment to be tailored to the needs of each dyad within the context of the manualized treatment. This mechanism of action does not necessarily inform the causality of preschool depression which remains largely un-tested. However, as has been demonstrated in other early interventions, parenting may be the key agent of change even when it is neither the sole nor central part of the etiology of the problem.

These findings must be interpreted as highly preliminary in light of several limitations. First, the small sample size limited the types of data analyses that could be used and conclusions about the findings. Second, obtaining self-reports about depressive symptoms in preschool children is not appropriate or feasible; therefore, reliance on parental report, which may be biased, is necessary. Although in general parents did not report elevated depressive symptoms, the potential for reporting bias due to depression must be considered. The use of observational measures and teacher reports minimizes this problem and will be investigated in future studies. Finally, this was an open treatment trial with a pre- post design. Therefore, the changes observed could have been due to regression to the mean, maturation, or the positive effects of expectancy alone. While we feel these limitations are unlikely to explain the large effect sizes found, firm conclusions about the efficacy cannot be made until data from the randomized controlled trial are available.

Conclusions

Findings from this open trial of this novel form of dyadic psychotherapy for preschool depression appear promising. However, we await the data from the more rigorous randomized controlled trial before any conclusions about the efficacy of this early intervention can be drawn. The potential for early and more effective psychotherapeutic intervention in this chronic and relapsing disorder, with a known early onset, may offer exciting new options for changing the trajectory of depressive disorders across the lifespan.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health (Bethesda, MD) grants R34-MH80163 (J.L.) and T32DA007261 (S.L).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Dr. Luby has received grant funding from the National Institute of Mental Health and NARSAD. She also receives royalties from Guilford Press for a book on childhood mental disorders.

References

- 1.Luby J, Heffelfinger A, Mrakotsky C, et al. Preschool major depressive disorder: preliminary validation for developmentally modified DSM-IV criteria. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:928–37. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200208000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luby J, Heffelfinger A, Mrakotsky C, et al. The clinical picture of depression in preschool children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:340–8. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200303000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luby JL, Si X, Belden AC, Tandon M, Spitznagel E. Preschool depression. Homotypic continuity and course over 24 months. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:897–905. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Egger HL, Angold A. Common emotional and behavioral disorders in preschool children: presentation, nosology, and epidemiology. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 2006;47:313–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luby JL, Heffelfinger A, Mrakotsky C, et al. Alterations in stress cortisol reactivity in depressed preschoolers relative to psychiatric and no-disorder comparison groups. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:1248–1255. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.12.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luby JL, Si X, Belden AC, et al. Preschool depression. Homotypic continuity and course over 24 months. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:897–905. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weisz JR, McCarty C, Valeri S. Effects of psychotherapy for depression in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2006;132:132–149. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phillips RD. How firm is our foundation? Current play therapy research. International Journal of Play Therapy. 2010;19:13–25. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urquiza AJ. The future of play therapy: Elevating credibility through play therapy research. International Journal of Play Therapy. 2010;19:4–12. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spivak G, Shure MB. Social adjustment of young children. San Franciso: Jossey-Bass; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shure MB. I can problem solve (ICPS): An interpersonal cognitive problem solving program for children. In: Pfeiffer SI, Reddy LA, editors. Innovative mental health interventions for children: Programs that work. New York: the Haworth Press, Inc; 2001. pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grave J, Blissett J. Is cognitive behavior therapy developmentally appropriate for young children? A critical review of the evidence. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24:399–420. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doherr L, Reynolds S, Wetherly J, Evans EH. Young children’s ability to engage in cognitive therapy tasks: Associations with age and educational experience. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2005;33:201–215. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Masek B, Henin A, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for 4-to 7-year-old children with anxiety disorders: A randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78:498–510. doi: 10.1037/a0019055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monga S, Young A, Owens M. Evaluating a cognitive behavioral therapy group program for anxious five to seven year old children: A pilot study. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26:243–250. doi: 10.1002/da.20551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Minde K, Roy J, Bezonsky R, Hashemi A. The effectiveness of CBT in 3–7 year old anxious children: Preliminary data. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;19:109–115. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scheeringa MS, Salloum A, Arnberger RA, et al. Feasibility and effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy for post traumatic stress disorder in preschool children: Two case reports. J Traumatic Stress. 2007;20:631–636. doi: 10.1002/jts.20232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eyberg SM. Tailoring and adapting parent-child interaction therapy to new populations. Educ Treat Children. 2005;28:197–201. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Toth SL, Maughan A, Manly JT, et al. The relative efficacy of two interventions in altering maltreated preschool children’s representational models: Implications for attachment theory. Dev Psychopathol. 2002;14:877–908. doi: 10.1017/s095457940200411x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lieberman AF. Child-parent psychotherapy: A relationship based approach to the treatment of mental health disorders in infancy and early childhood. In: Sameroff AJ, McDonough SC, Rosenblum KL, editors. Treating parent-infant relationship problems: Strategies for intervention. New York: Guilford Press; 2004. pp. 97–122. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brinkmeyer M, Eyberg SM. Parent-child interaction therapy for oppositional children. In: Kazdin AE, Weisz J, editors. Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hood KK, Eyberg SM. Outcomes of parent-child interaction therapy: mothers’ reports of maintenance three to six years after treatment. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2003;32:419–29. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3203_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chase RM, Eyberg SM. Clinical presentation and treatment outcome for children with comorbid externalizing and internalizing symptoms. J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22:273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luby J, Belden A. Mood disorders and an emotional reactivity model of depression. In: Luby J, editor. Handbook of preschool mental health: development, disorders, and treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. pp. 209–230. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herschell AD, Calzada EJ, Eyberg SM, McNeil CB. Clinical issues in parent-child interaction therapy. Cogn Behav Pract. 2002;9:16–27. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fraiberg S, Adelson E, Shapiro V. Ghosts in the nursery: A psychoanalytic approach to the problems of impaired infant-mother relationships. In: Fraiberg S, editor. Selected writing of Selma Fraiberg. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press; 1987. pp. 100–136. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eyberg SM. Parent-child interaction manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1999. 1999 Treatment Integrity Checklists. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luby J, Heffelfinger A, Koenig-McNaught A, et al. The preschool feelings checklist: A brief sensitive screening measure for depression in young children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:708–717. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000121066.29744.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Egger HL, Ascher AA. Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA) Duke University Medical Center; Durham, NC: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Egger HL, Erkanli A, Keeler G, et al. Test-retest reliability of the Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:538–549. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000205705.71194.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Armstrong JM, Goldstein LH. The MacArthur Working Group on Outcome Assessments. Health and Behavior Questionnaire. In: Kupfer DJ, editor. Manual for the MacArthur Health and Behavior Questionnaire (HBQ 1.0) University of Pittsburgh; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hodges K. The Preschool and Early Childhood Functional Assessment Scale (PECFAS) Ypsilanti, MI: Eastern Michigan University; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murphy JM, Pagano ME, Ramirez A, et al. Validation of the Preschool and Early Childhood Functional Assessment Scale (PECFAS) J Child Fam Stud. 1999;3:343–356. doi: 10.1023/A:1022071430660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gur RC, Ragland JD, Moberg PJ, et al. Computerized neurocognitive scanning: I. Methodology and validation in healthy people. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25:766–776. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00278-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gur RC, Richard J, Hughett P, et al. A cognitive neuroscience-based computerized battery for efficient measurement of individual difference: Standardization and initial construct validation. J Neurosci Methods. 2010;187:254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2009.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beck AT. Beck Depression Inventory. The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eyberg SM. Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory. Gainesville: University of Florida; 1974. Therapy Attitude Inventory. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eyberg SM. Consumer satisfaction measures for assessing parent training programs. In: VendeCreek L, Knapp S, Jackson TL, editors. Innovations in clinical practice: A source book. Sarsota, FL: Professional Resource Press; 1993. pp. 377–382. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hedges LV, Olkin I. Statistical methods for meta-analysis. Orlando: Academic Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Michael KD, Crowley SL. How effective are treatments for child and adolescent depression? A meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2002;22:247–269. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(01)00089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Belden A, Luby JL. Preschoolers’ depression severity and behaviors during dyadic interactions: The mediating role of parental support. J Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:213–222. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000189133.59318.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luby J, Sullivan J, Belden A, et al. An observational analysis of behavior in depressed preschoolers: further validation of early onset depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:203–212. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000188894.54713.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, et al. Parental reactions to children’s negative emotions: longitudinal relations to quality of children’s social functioning. Child Dev. 1996;70:513–534. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chiarello MA, Orvaschel H. Patterns of parent-child communication: Relationship to depression. Clin Psychol Rev. 1995;15:395–407. [Google Scholar]