Abstract

We investigated the synergism between influenza virus and Streptococcus pneumoniae, particularly the role of deletions in the stalk region of the neuraminidase (NA) of H2N2 and H9N2 avian influenza viruses. Deletions in the NA stalk (ΔNA) had no effect on NA activity or on the adherence of S. pneumoniae to virus-infected human alveolar epithelial (A549) and mouse lung adenoma (LA-4) cells, although it delayed virus elution from turkey red blood cells. Sequential S. pneumoniae infection of mice previously inoculated with isogenic recombinant H2N2 and H9N2 influenza viruses displayed severe pneumonia, elevated levels of intrapulmonary proinflammatory responses, and death. No differences between the WT and ΔNA mutant viruses were detected with respect to effects on postinfluenza pneumococcal pneumonia as measured by bacterial growth, lung inflammation, morbidity, mortality, and cytokine/chemokine concentrations. Differences were observed, however, in influenza virus-infected mice that were treated with oseltamivir prior to a challenge with S. pneumoniae. Under these circumstances, mice infected with ΔNA viruses were associated with a better prognosis following a secondary bacterial challenge. These data suggest that the H2N2 and H9N2 subtypes of avian influenza A viruses can contribute to secondary bacterial pneumonia and deletions in the NA stalk may modulate its outcome in the context of antiviral therapy.

INTRODUCTION

Influenza virus infection in humans usually leads to a brief illness that varies in severity, depending on multiple viral and host factors. Fatalities are often linked to secondary infections with bacterial pathogens. Streptococcus pneumoniae is among the most important bacterial pathogens associated with postinfluenza pneumonia, and it is the leading cause of community-acquired pneumonia in humans (1, 34). S. pneumoniae bacteria are commensals of the human respiratory tract and colonize up to 70% of individuals without causing clinical symptoms.

Several factors have been proposed to contribute to viral-bacterial synergism, including dysfunctional neutrophils and alveolar macrophages, increased bacterial adherence to the epithelium due to upregulation of cryptic receptor expression on its surface, and influenza virus-induced immunosuppression (16). The neuraminidase (NA) protein of influenza A viruses is one of the viral factors identified in this viral-bacterial synergism (17, 21, 22). The specific NA activities of representative human H2N2 and H3N2 subtype viruses isolated from 1957 to 1997 correlated with their abilities to cause secondary bacterial infections (22). Except for the 1918 pandemic H1N1 subtype, the mortality and secondary bacterial pneumonia rates have been higher following H3N2 infections than following H1N1 infections, suggesting an important role for the N2 subtype in this regard (17, 21, 22).

The influenza virus NA is a type II membrane glycoprotein found on the viral surface along with the hemagglutinin (HA) glycoprotein (5). NA promotes the release of the virus from infected cells and prevents HA-mediated virus self-aggregation by cleaving off sialic acids of viral and cellular glycoconjugates (36). The NA stalk region varies considerably in length, even within the same subtypes, and plays a role in replication and pathogenesis (13). Deletions in the NA stalk are characteristic of the adaptation of influenza viruses from aquatic birds and poultry, particularly chickens (19, 29). Variations in the NA stalk have been shown to play a role in the virulence of highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza viruses (38). Recently, we showed that adapting H2N2 and H9N2 avian influenza A viruses isolated from wild waterfowl to quail and chickens resulted in significant deletions in the NA stalk region and increased replication in both chickens and mice (8, 29).

Wild aquatic birds are the reservoirs of all known subtypes of influenza A viruses, and some of these are occasionally transmitted to poultry species. The H9N2 subtype is endemic to poultry in many Eurasian countries and has occasionally caused clinical respiratory diseases in humans (2, 20). H2N2 viruses were responsible for the emergence of the 1957 influenza pandemic. Phylogenetic analysis of avian H2N2 influenza viruses has revealed little antigenic divergence from the 1957 pandemic H2N2 strain. Interregional transmission of H2 viruses between North America and Eurasia has been documented (12, 24). Based on the genetic and transmissibility characteristics of both H2N2 and H9N2 viruses, it is possible that the surface genes of these viruses could reassort with human influenza viruses, creating reassortants with pandemic potential. It has been recently shown that reassortant viruses derived from the H9N2 and 2009 pandemic H1N1 strains were able to be transmitted efficiently in ferrets and some were more pathogenic in mice than the parental viruses were (9, 32). In this study, we determined whether the length of the stalk region of N2 NAs from avian H2N2 and H9N2 viruses has an effect in promoting secondary bacterial infection in the mouse model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses.

Mouse-adapted influenza virus A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 (H1N1) (PR8) was used as a control and to create viruses with isogenic backgrounds. Quail- and chicken-adapted viruses (WT and ΔNA H2N2, respectively) carrying full-length and 27-amino-acid (aa) deletions in the NA stalk region, respectively, have been previously described and were derived from the A/mallard/Potsdam/178-4/1983 (H2N2) virus (29). Quail- and chicken-adapted viruses (WT and ΔNA H9N2, respectively) with full-length and 21-aa deletions in the NA stalk region, respectively, were previously described and were derived from the A/duck/Hong Kong/702/1979 (H9N2) virus (8, 28). Recombinant viruses with the HA and NA (WT and ΔNA) gene segments of avian viruses with an isogenic background from the PR8 virus were generated by reverse genetics (7) (Table 1). The HA, NA, and M genes were sequenced to confirm the identities of the viruses recovered. Viruses were grown in embryonated chicken eggs, and the allantoic fluid was collected, aliquoted, titrated in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells (50% tissue culture infective doses [TCID50]) and eggs (50% egg infective dose [EID50]), and stored at −80°C until used.

Table 1.

Titers of viruses and their virulence in mice

| Virusa | TCID50 (log10/ml) | EID50 (log10/ml) | MLD50 (log10 EID50) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A/PR/8/34 | 9.192 | 10.199 | 2.565 |

| WT H2N2 | 9.342 | 10.199 | 6.231 |

| ΔNA H2N2 | 8.899 | 9.949 | 5.648 |

| WT H9N2 | 9.699 | 9.949 | 6.315 |

| ΔNA H9N2 | 9.342 | 9.449 | 5.815 |

Viruses contain the same set of internal gene segments derived from the PR8 strain.

Pneumococci.

S. pneumoniae D39, a type 2 encapsulated strain, was grown at 37°C in tryptic soy broth (TSB; Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) supplemented with 5% CO2 for 6 h or until log phase. The bacterium was mixed with 15% glycerol and frozen at −80°C. The pneumococcus concentration was measured by determining the absorbance at 600 nm and by quantitation on TSB agar supplemented with 3% (vol/vol) sheep erythrocytes (Lampire Biologicals, Pipersville, PA).

Bacterial adherence assay.

Human lung carcinoma A549 and murine lung LA-4 cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were seeded at 5 × 105/well into 24-well plates (Costar, Corning Inc., Corning, NY). An adhesion assay was performed as described previously, with minor modifications (17). Briefly, the cells were infected with influenza viruses at a multiplicity of infection of 1 at 37°C for 1 h and then incubated with 10 CFU/cell of pneumococci for 2 h at 37°C. The cell monolayers were washed to remove loosely adherent pneumococci, incubated with 1× trypsin-EDTA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) to detach the cells from the plate, and finally lysed using 0.025% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich). Control cells were treated identically without the addition of virus. The cell lysates were serially diluted 10-fold in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and plated on tryptic soy agar (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 3% (vol/vol) sheep erythrocytes to determine the number of bacterial cells adhering to the cell monolayers.

NA activity assay.

Viruses were grown in eggs, concentrated by ultracentrifugation at 35,000 rpm for 2 h at 4°C, and further purified by using 10 to 40% discontinuous sucrose gradients. The purified virus was resuspended in NTE buffer (100 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.4], 1 mM EDTA). The protein concentration in purified virus samples was measured by determining the A280 using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Equal amounts of purified viral proteins were serially diluted 2-fold in MES assay buffer [32.5 mM 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid, 4 mM CaCl2, pH 6.5] and allowed to react with 10 μM 2′-(4-methylumbelliferyl)-N-acetylneuraminic acid (Mu-NANA) substrate (Sigma-Aldrich). The fluorescence of 4-methylumbelliferone cleaved from the Mu-NANA substrate was measured on a Victor V multilabel plate reader (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA) with 355- and 460-nm excitation and emission filters, respectively. NA activity was also measured by using the NA-Star influenza virus NA inhibitor resistance detection kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and following the manufacturer's recommendations.

Virus elution assay.

The ability of viruses to be eluted from erythrocytes was determined as described previously (3). Briefly, viruses were serially diluted in calcium saline buffer (6.8 mM CaCl2, 150 mM NaCl in 20 mM borate buffer, pH 7.2) and incubated with 50 μl of 0.5% chicken or turkey erythrocytes (Lampire Biologicals) at 4°C for 1 h in microtiter plates. Then the plates were transferred to 37°C, and the reduction of HA titers was monitored periodically for 24 h.

Postinfluenza S. pneumoniae mouse challenge.

Six-week-old female BALB/c mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Frederick, MD) and maintained under animal biosafety level 2 conditions in the Department of Veterinary Medicine. Animal studies were conducted under protocols R-09-93 and R-10-65 and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Maryland, College Park. Mice were handled under general anesthesia with inhaled 2.5% isoflurane (Abbot Laboratories, North Chicago, IL). Mouse 50% lethal doses (MLD50s) were determined as previously described (23), using groups of mice (n = 3) infected with serial dilutions (10−1 to 10−7) of the viral stocks.

Influenza viruses (0.5 MLD50) were administered intranasally in a volume of 50 μl to anesthetized mice held in an upright position. Virus-infected mice were challenged at 7 days postinfection (dpi) with 102, 103, 104, or 105 CFU of pneumococci per mouse. For experiments involving therapeutic treatment of influenza virus-infected mice with commercially available oseltamivir (Tamiflu; Hoffman-La Roche, Nutley, NJ), mice were given oseltamivir at a dose of 10 mg/kg/day twice a day for 5 days by oral gavage starting at 48 h postinfection (hpi). Oseltamivir treatment was stopped on the day that mice were challenged with S. pneumoniae (104 CFU/mouse).

Mice were weighed and monitored daily for disease signs and death. Mice that lost ≥25% of their body weight were euthanized and considered dead on that day. At 7 dpi and at 1 and 3 days post-pneumococcal challenge (dppc), lungs were collected; homogenates were prepared and used to determine viral and bacterial titers.

Cytokine and chemokine analysis.

Mouse lung homogenates collected at 1 dppc were centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C, and the supernatants were frozen at −80°C until analyzed. Concentrations of interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, IL-10, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and the chemokines KC and macrophage inflammatory protein 1 alpha (MIP-1α) were measured by using a mouse 6-Plex Luminex-100 system (Cytokine Core Laboratory, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD).

Histopathology.

At 7 dpi and 2 dppc, mice were bled and euthanized and their lungs were removed (2 mice/group). The lungs were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin. Lung tissues were embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 μm, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). A board-certified veterinary pathologist who was blinded to the groups examined the slides. Lung tissue sections were examined microscopically for histopathological alterations and the presence of inflammation in the lung parenchyma and airways.

Statistical analysis.

The data are expressed as arithmetic means ± standard errors. An unpaired Student t test was performed to determine the level of significance of differences between the means of two groups. Cytokine and chemokine levels of groups were compared by analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni's posttest correction to determine which groups had significant differences. Survival data of groups of mice were compared with the log rank (Mantel-Cox) test. P values of <0.05 were considered significant. All statistical analyses were done with Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA).

RESULTS

Adherence of S. pneumoniae to virus-infected human and murine lung epithelial cells.

The level of S. pneumoniae adherence to epithelial cells depends upon the degree of NA activity of different influenza A viruses (22). We have previously adapted duck H2N2 and H9N2 avian influenza viruses to quail and chickens. The resulting strains contained deletions in the stalk region of NA (ΔNA) that favor viral replication in chickens. The ΔNAs of H2N2 and H9N2 viruses have 27- and 21-aa deletions in the stalk region, respectively (8, 29). To test the effect of NA length on the adherence of S. pneumoniae to cultured cells, we infected human A549 and murine LA-4 cells with influenza A virus and then superinfected them with bacteria. After 2 h of incubation at 37°C, the level of adhesion of S. pneumoniae to virus-infected A549 and LA-4 cells was increased compared to the level of adhesion to mock-infected cells (Fig. 1A and B, respectively). The levels of pneumococcal adhesion to A549 and LA-4 cells were similar for the H2N2, H9N2, and PR8 strains. Additionally, there were no significant differences in the adhesion of pneumococci between the WT and ΔNA strains, suggesting that NA length plays no role in S. pneumoniae adhesion in vitro.

Fig 1.

Bacterial adherence is increased in influenza virus-infected A549 and LA-4 cells. A549 (A) and LA-4 (B) cells were infected with PR8, WT, and ΔNA avian influenza A H2N2 or H9N2 virus or mock infected and then infected with S. pneumoniae strain D39 (Sp). Levels of bacterial adhesion are expressed as percentages of the level measured in mock-infected cells (the level of bacterial adherence to mock-infected cells was set at 100% [not shown]). The results are displayed as means and ranges (not standard deviations) of six (A549 cells) and three (LA-4 cells) consecutive independent experiments with four replicates in each experiment. No statistically significant differences were found. (C) NA activities of avian influenza A viruses. The NA activities of concentrated and purified PR8, WT, and ΔNA avian influenza A H2N2 and H9N2 viruses were measured by a Mu-NANA substrate fluorescence assay. NA activities are expressed as percentages of the activity of A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) NA, which was arbitrarily set at 100%. The data are displayed as means and ranges of three independent experiments containing four replicates of each virus. Differences in NA activity are not statistically significant. (D, E) WT and ΔNA mutant avian viruses differ in the ability to elute from erythrocytes. Twofold dilutions of virus containing 1:128 HA units were incubated with equal volumes of 0.5% chicken (D) or turkey (E) erythrocytes at 4°C for 1 h. The reduction in HA units was recorded for 24 h after incubation at 37°C.

Stalk deletions in N2 NA affects elution of virus bound to turkey erythrocytes.

NAs with a short stalk were found to be inefficient at releasing progeny virions, which may be caused by the active site having limited access to the substrate (6). The NA activity in purified virus preparations of WT and ΔNA mutant H2N2 and H9N2 strains were measured using the Mu-NANA substrate and compared to that of the control PR8 virus. The WT and ΔNA strains had similar levels of NA activity in both avian virus subtypes (Fig. 1C). We also found the same NA activity using a different method, the NA star influenza virus NA inhibitor resistance detection kit (data not shown).

Previous studies showed that NA stalk length affects the elution of viruses bound to erythrocytes, but there was no correlation between NA stalk length and enzymatic activity with large (fetuin) and/or small (sialyllactose) substrates (3, 6). We performed virus elution assays using chicken and turkey erythrocytes. From chicken erythrocytes, the WT viruses showed 4- to 8-fold reductions in HA units in a span of 24 h of incubation at 37°C, whereas the corresponding ΔNA viruses showed an only 2-fold reduction (Fig. 1D). When we used turkey erythrocytes, the WT viruses were more efficiently eluted, with a 128-fold reduction in HA units. The ΔNA strain elution was delayed and produced only 4- to 8-fold reductions during the same 24-h period (Fig. 1E). Taken together, these results suggest that NA deletions in avian H2N2 and H9N2 viruses result in delayed virus release from erythrocytes, possibly due to differences in the sialic acid milieu on the surfaces of different cells.

Postinfluenza S. pneumoniae challenge of mice results in secondary pneumonia independent of NA stalk length.

In order to study the viral-bacterial synergism in the mouse model, recombinant influenza viruses that differed only in the HA and NA gene segments were rescued with the six internal gene segments from the PR8 virus. All of the recombinant viruses grew to high titers in embryonated chicken eggs and caused morbidity and death in mice (Table 1). The EID50s of all of the recombinant viruses were similar to that of the parental PR8 virus. The MLD50 of the recombinant viruses with avian influenza virus HA and NA genes required 3 to 4 log10 more virus than the mouse-adapted parental PR8 strain, which is probably due to the fact that the H2N2 and H9N2 surface proteins are not well adapted to replicate in mice. No significant differences in the EID50 and MLD50 titers were observed for the WT NA and ΔNA N2 recombinant viruses.

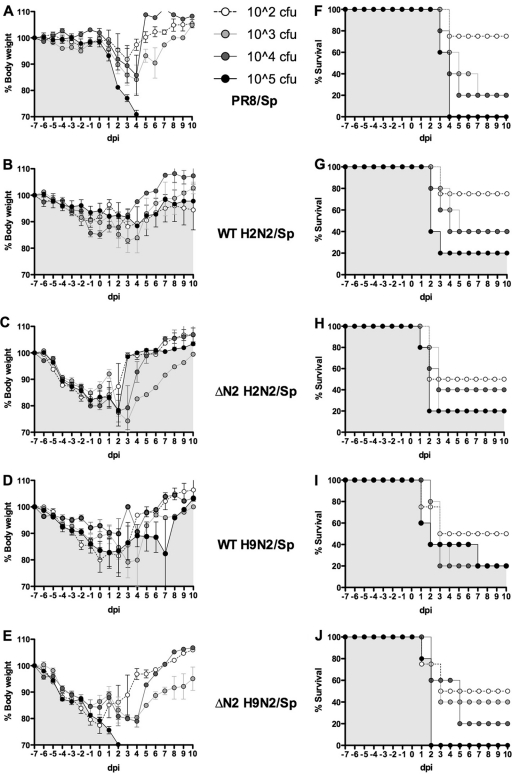

BALB/c mice were infected with 0.5 MLD50 of influenza virus and challenged at 7 dpi with 102, 103, 104, or 105 CFU of S. pneumoniae (Fig. 2). Mice were monitored for changes in body weight and disease signs for 21 dpi (14 dppc; graphs show only up to 10 dppc). In the PR8 virus-infected group, there was no change in body weight after virus inoculation; however, after pneumococcal infection, mice exhibited a ≥20% body weight loss when large bacterial doses were administered (Fig. 2A). Mice in the WT and ΔNA (H2N2 and H9N2) groups started losing body weight at 3 dpi and continued to lose 10 to 20% of their body weight until a pneumococcal challenge (Fig. 2B to E). Interestingly, the ΔNA (H2N2 and H9N2) groups showed a more pronounced body weight loss prior to challenge than the WT NA counterparts did, although the mechanism behind this effect remains unknown. A rough coat, reduced activity, and reduced body weight were more pronounced after pneumococcal infection in all of the previously infected groups. Disease signs did not differ significantly between the WT and ΔNA groups. No significant differences in mouse survival were observed in these groups either, irrespective of both the length of the NA gene and the bacterial dose (Fig. 2F to J). Significant mortality was observed at 2 dppc with 105 CFU in mice that previously received the WT or ΔNA H2N2 virus or the ΔNA H9N2 virus, whereas those that received the WT H9N2 virus showed comparatively delayed death (Fig. 2G to J).

Fig 2.

Postinfluenza secondary pneumococcal pneumonia-induced morbidity and mortality in mice. Groups of mice (n = 5) were infected with 0.5 MLD50 of PR8 virus or WT or ΔNA mutant H2N2 and H9N2 recombinant viruses carrying a PR8 isogenic background. Control mice were mock infected with PBS. Mice were then challenged at 7 dpi with different doses of pneumococci. The percentage of body weight lost, as a measure of morbidity (A to E), and survival (F to J) was plotted. Error bars indicate standard deviations. Control mice receiving only PBS or pneumococci had no weight loss, and 100% survived (data not shown). The differences observed within and between the WT and ΔNA mutant viruses at different bacterial challenge dose levels are not statistically significant by the log rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Sp, S. pneumoniae.

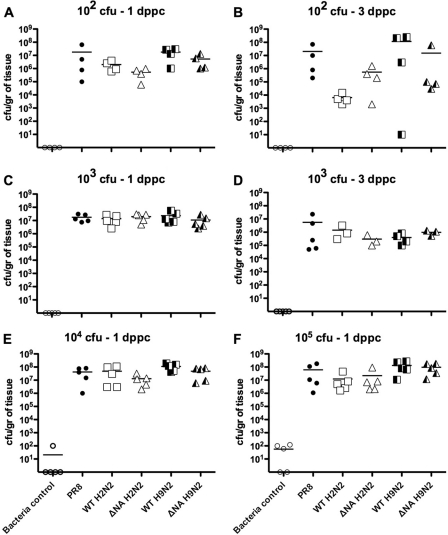

Viral titers were determined in the lungs of virus-infected mice at 7 dpi and at 1 and 3 dppc. In the PR8 virus-only and PR8-S. pneumoniae groups, virus titers of 105 TCID50/g of tissue were detected at 7 dpi and 1 dppc; however, at 3 dppc, the viral titers were either low or undetectable in these two groups (not shown). No virus titers above the limit of detection (≤0.7 log10 TCID50/g) were observed at 7 dpi and 1 dppc in mice infected with the avian WT and ΔNA recombinant viruses (data not shown). With respect to the bacterial load, significantly higher titers (CFU/g of tissue) were found in the lungs of mice that were previously infected with influenza viruses than in controls infected with bacteria alone (Fig. 3). These results show that influenza virus infection increased pneumococcal colonization and facilitated the replication of S. pneumoniae in the lower respiratory tract. The lungs of mouse groups that were challenged with either 102 or 103 CFU of bacteria after virus infection showed 1 to 2 log10 reductions in pneumococcal titers at 3 dppc versus 1 dppc (Fig. 3A to D). Significant bacterial load variations were observed at 3 dppc in groups that were challenged with 102 CFU (Fig. 3B). In contrast, at 1 dppc, lungs contained up to 108 CFU/g of tissue, irrespective of the bacterial challenge dose (Fig. 3A, C, E, and F) and no significant differences between the WT and ΔNA recombinant viruses were observed. No pneumococcal load was determined at 3 dppc in the groups challenged with 104 and 105 CFU of bacteria due to significant mortality at 2 dppc.

Fig 3.

Pulmonary bacterial loads during secondary bacterial infection. Mice (n = 5) were infected with the indicated viruses and challenged at 7 dpi with S. pneumoniae (102 [A and B], 103 [C and D], 104 [E], or 105 [F] CFU/mouse). Lung bacterial titers were measured at 1 and 3 dppc and are expressed as CFU/g of lung homogenate. No statistically significant differences between the bacterial loads of the WT and ΔNA mutant virus groups were observed.

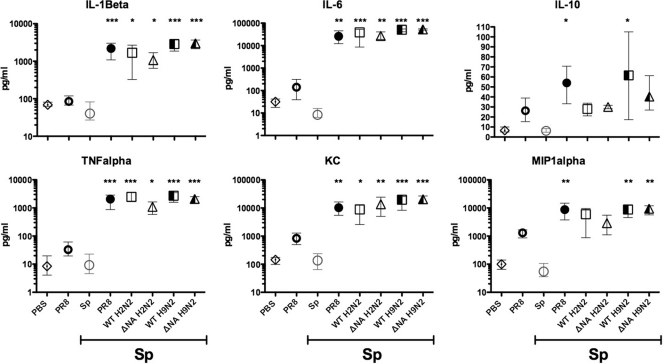

Cytokine and chemokine responses are exacerbated in postinfluenza S. pneumoniae challenge mice.

To determine the pulmonary cytokine and chemokine responses during secondary bacterial pneumonia following influenza virus infection, the concentrations of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, KC, and MIP-1α in mouse lung homogenates were measured. The levels of cytokines and chemokines at 1 dppc in the lungs of mice mock infected or infected with S. pneumoniae alone were similar to each other (Fig. 4). Increased cytokine responses were evident in PR8-infected mice (≤10-fold compared to controls); however, they were exacerbated following a bacterial challenge (20- to 1,000-fold, depending on the cytokine, at 1 dppc compared to negative controls). Consistent with this observation, there was also exacerbation of cytokine responses in the WT and ΔNA virus groups after a challenge with pneumococci (1 dppc, Fig. 4). Significant increases in the levels of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, KC, and MIP-1α were observed after a bacterial challenge in mice previously infected with influenza virus compared to those in mock-infected controls. However, only levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α were significantly increased compared to those in PR8-infected controls not bacterial challenged. Of note, there were significant variations in the levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. There was an approximately 6-fold increase in IL-10 expression in mice infected with PR8 virus alone compared to that in either negative controls or controls infected with bacteria alone. The IL-10 response increased another 2-fold in PR8 mice challenge with pneumococci, which was found to be statistically significant (≥10-fold over basal levels). A similar pattern was observed in the H9N2-S. pneumoniae group. However, the WT and ΔNA H2N2 recombinant virus groups and the ΔNA H9N2 group showed no exacerbated expression of IL-10 following a secondary bacterial challenge compared to the control group given PR8 virus alone. Significant MIP-1α increases were observed after a bacterial challenge in mice previously infected with PR8 and either the WT or ΔNA H9N2 virus but not with either the WT or ΔNA H2N2 virus. These studies suggest HA subtype-dependent effects which can modulate cytokine responses during infection and affect the response to a bacterial challenge. Understanding such mechanisms is beyond the scope of the present report.

Fig 4.

Postinfluenza S. pneumoniae (Sp) infection exacerbates pulmonary cytokine and chemokine levels. Mice (n = 5) were infected with the indicated viruses and challenged at 7 dpi with 105 CFU of S. pneumoniae. Lung homogenates were collected at 1 dppc and assayed for cytokine concentrations. Cytokine levels for each group are represented as means and ranges. *, **, and *** denote statistically significant differences of P < 0.05, P < 0.01, and P < 0.001, respectively, determined by one-way ANOVA (compared to the group infected with PR8 virus alone).

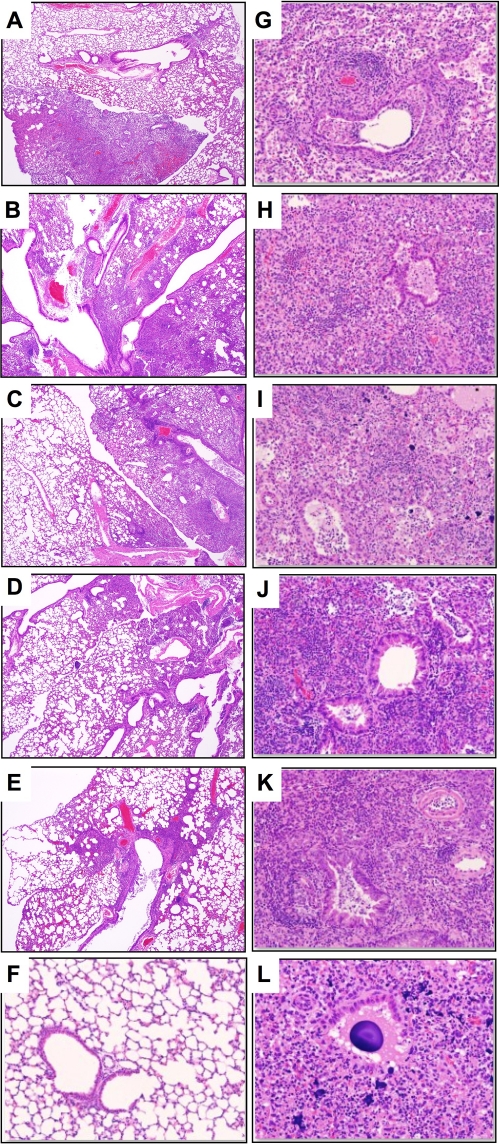

Histopathological studies of coinfected mouse lungs are consistent with secondary bacterial bronchopneumonia.

To understand the severity of the lung inflammatory response to secondary S. pneumoniae in mice primed with avian H2N2 and H9N2 viruses, histopathological changes in lung sections were examined at 7 dpi and 2 dppc. At 7 dpi, the lungs in the PR8 virus-infected mouse group showed mild inflammation and minimal necrosis and hyperplasia of the bronchiolar and alveolar epithelium (Fig. 5A). The mice infected with both WT and ΔNA recombinant viruses had mild-to-moderate hyperplasia and inflammation of the bronchiolar and alveolar epithelium along with infiltration of lymphocytes and macrophages (Fig. 5B to E). The lesions in the lung parenchyma were more widespread in mice infected with the PR8 and H2N2 recombinant viruses (Fig. 5A to C) than in their H9N2-infected counterparts (Fig. 5D and E). At 2 dppc, lungs from mock-infected mice had normal histopathological features (not shown). Lungs of mock-infected mice challenged with pneumococci had few foci of macrophages and neutrophils in the peribronchiolar region at 2 dppc (Fig. 5F). PR8-infected (virus-only control) mice had minimal necrosis and inflammation in the bronchiolar, peribronchiolar, and alveolar regions of the lung parenchyma at 7 dpi (Fig. 5G). In contrast, lungs of mice virus infected and then bacterially challenged showed severe inflammatory responses consistent with secondary pneumococcal pneumonia (Fig. 5H to L). The H2N2-S. pneumoniae and H9N2-S. pneumoniae groups (Fig. 5H to K) were characterized by mild-to-moderate hyperplasia of the bronchiolar epithelium, severe and diffuse inflammation of the lobes, suppurative fibrinous pleuritis, and the presence of inflammatory cells (neutrophils and macrophages). The pneumonic process extended to the pleura, resulting in marked pleuritis. These observations are similar to those of the lungs of the PR8-S. pneumoniae mouse group, which showed moderate necrotizing bronchitis and severe diffuse alveolar inflammation (Fig. 5L). No difference in the severity of inflammation between the WT and ΔNA virus groups was observed. However, consistent with the lack of exacerbated IL-10 responses, the severity of inflammation was higher in the WT H2N2, ΔNA H2N2, and ΔNA H9N2 groups than in the WT NA H9N2 group.

Fig 5.

Histopathologic changes in lungs of mice with secondary bacterial pneumonia. The images shown are H&E-stained sections of lungs collected at 7 dpi from BALB/c mice infected with 0.5 MLD50 of PR8 (A), WT H2N2 (B), ΔNA mutant H2N2 (C), WT H9N2 (D), or ΔNA mutant H9N2 (E) virus. All viruses carry the PR8 isogenic background. Original magnification, ×40. (F to M) Mice were infected with the indicated viruses and then challenged at 7 dpi with 104 CFU of pneumococci. Lungs were collected at 2 dppc. Representative H&E-stained sections are shown at ×200 magnification. (F) Mock-infected mice challenged with pneumococci. (G) Mice infected with PR8 and then mock challenged with PBS. The virus-S. pneumoniae groups correspond to WT H2N2 (H), ΔNA mutant H2N2 (I), WT H9N2 (J), ΔNA mutant H9N2 (K), and PR8 (L).

Oseltamivir treatment improves the prognosis of secondary bacterial infection in mice previously infected with ΔNA viruses.

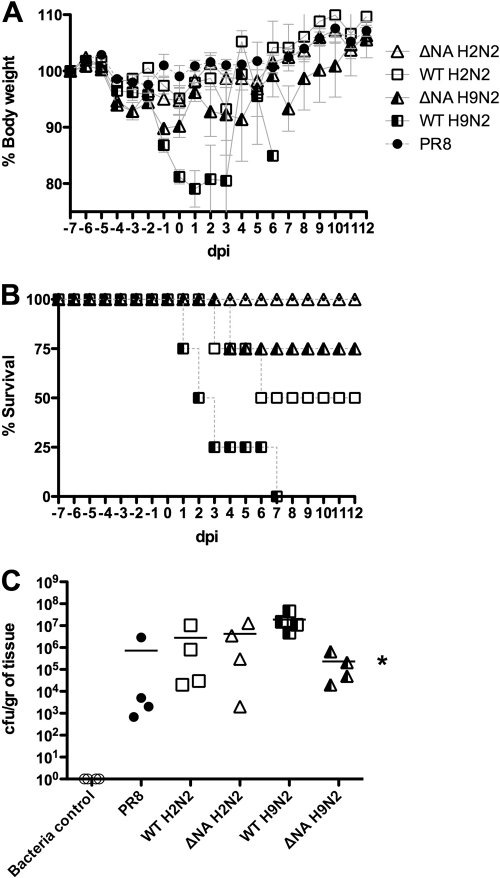

Anti-influenza drug therapy is thought to lessen the chance of a secondary bacterial infection and therefore improve the prognosis of influenza virus infections (15). We studied whether the therapeutic administration of oseltamivir to virus-infected mice would reduce the impact of secondary bacterial pneumonia in terms of morbidity and mortality. Oseltamivir treatment was initiated at 48 hpi and continue for the next 5 days (Fig. 6). On the last day of antiviral therapy, mice were challenge with pneumococci (104 CFU/mouse). Consistent with a previous report (15), PR8-infected mice that were treated with oseltamivir did not lose body weight and showed reduced pneumococcal CFU counts at 1 dppc (compare Fig. 3E and 6C) and the mice survived (n = 4). ΔNA mutant virus-infected, oseltamivir-treated mice showed improved survival compared to nontreated mice (80 to 100% [Fig. 6B] compared to 20 to 40% [Fig. 2H and J]). However, oseltamivir treatment of WT H2N2 and H9N2 virus-infected mice did not improve their survival significantly (compare Fig. 6B with Fig. 2G and I). Bacterial loads at 1 dppc showed more variations in mice previously treated with oseltamivir (Fig. 6C) than did those of mice that did not receive antiviral treatment (Fig. 3E). Also, a significant bacterial load decrease was observed in the ΔNA H9N2 group that received oseltamivir treatment compare to a similar group that had been previously infected with the WT H9N2 virus. Histopathological analyses at 2 dppc were consistent with the survival results, with mice in the PR8-S. pneumoniae group showing normal lungs and those in the WT H9N2-S. pneumoniae group showing the most severe lung lesions, similar to those of untreated, WT H9N2-S. pneumoniae-infected mice (data not shown). Other groups showed mild-to-moderate hyperplasia in the bronchial epithelium and focalized moderate-to-severe interstitial inflammation of the alveoli (data not shown). These results suggest that therapeutic treatment with oseltamivir has the potential to improve the survival of secondary bacterial pneumonia, although there are factors that may influence its effectiveness.

Fig 6.

Oseltamivir treatment reduces secondary bacterial pneumonia in ΔNA mutant H2N2 and H9N2 virus-infected mice. Mice (n = 8) were infected with 0.5 MLD50 of the indicated viruses and treated with oseltamivir for 5 days, starting at 48 hpi, and then challenged at 7 dpi with 104 CFU of S. pneumoniae. (A) Mean percentage of body weight lost ± standard deviation. (B) Survival. (C) At 1 dppc, 4 mice/group were sacrificed to determine bacterial lung titers expressed as CFU/g of lung homogenate. An asterisk denotes a statistically significant difference between the WT and ΔNA mutant H9N2 viruses (P < 0.05 by Student t test).

DISCUSSION

Influenza virus infection and its complications are among the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Influenza virus infections are expressed clinically as primary viral pneumonias and acute respiratory distress syndrome and are occasionally associated with secondary bacterial pneumonia due to superinfection with bacterial pathogens. With the exceptions of the 1918 pandemic and H5N1 avian influenza viruses, primary viral pneumonia is not the major cause of death (34). In general, influenza virus infection can induce bronchitis and pneumonia, but severe lethal pneumonia is usually seen when complications involve bacterial infections. Superinfection with S. pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, or Haemophilus influenzae has been well documented during influenza pandemics and epidemics and was shown to be a typical cause of death (16). Although, in general, influenza A viruses can induce secondary bacterial pneumonia, excess mortality appears to be subtype dependent (26, 35, 37). The viral NA is one of the virulence factors that cause this difference in excess mortality (17, 22). Studies of several human viruses within the N2 subtype isolated from 1957 to 1997 have shown that differences in NA activity correlated with their abilities to cause secondary bacterial infections (22). It has been speculated that deletions in the NA stalk are associated with the adaptation of influenza viruses to land-based poultry (11, 14). The avian H5N1 and H9N2 viruses that were transmitted to humans in 1997 and 1999, respectively, contained deletions in their NA stalk regions. H5N1 influenza A viruses with different NA stalk motifs differ in virulence and pathogenesis in chickens (38). The chicken-adapted H2N2 and H9N2 subtypes used here have 27- and 21-aa deletions, respectively, in the stalk region and showed more efficient replication in chickens than the parental viruses (8, 29). Since there were no prior studies looking at the effect of NA stalk length in avian influenza viruses in promoting secondary bacterial pneumonia, we examined its effect in the context of H2N2 and H9N2 avian influenza viruses. To avoid confounding factors unrelated to the NA, we prepared recombinant viruses within the context of an isogenic background derived from the PR8 strain. We found no differences between the WT and ΔNA mutant viruses in terms of promotion of secondary pneumococcal pneumonia in mice with respect to bacterial growth, lung inflammation, and mortality. This is the case even at a stage at which the viruses appear to have been cleared from the lungs or at least are at concentrations below the limit of detection. Significant differences were observed, however, in mice that received oseltamivir treatment after influenza virus infection. Mice infected with the PR8 virus or the ΔNA mutant viruses and then treated with oseltamivir for 5 days starting at 48 dpi showed significant (80 to 100%) improvement in survival following a bacterial challenge. In contrast, mice infected with the WT H2N2 and H9N2 viruses showed no significant improvement in survival under the same conditions. There are several considerations that might explain these observations. Although NA activity was indistinguishable among the different viruses, elution from turkey red blood cells was delayed in the ΔNA mutant viruses compared to that of their wild-type counterparts, which suggests limited accessibility to certain sialic acid substrates, despite equally active catalytic sites. These results were in accordance with earlier studies that concluded that there was no apparent relationship between the elution activities of the ΔNA mutant viruses and their enzymatic activity (3, 6). Another consideration is the virus inoculum. Even though mice were inoculated with 0.5 MLD50 of virus, the amount of virus particles representing such a dose of the PR8 strain (∼2 log10 EID50) is very different from that of the other viruses (∼6 log10 EID50). A larger virus inoculum would translate into more cells being targeted for infection, and although the replication of the H2N2 and H9N2 viruses themselves may not be as effective as that of PR8, the initial production and activity of NA are expected to be more widespread. It is conceivable that at these virus doses, deletions in the NA stalk do not affect the virus's ability to promote secondary bacterial infections. Only after oseltamivir treatment is it then possible to dissect the limitations of the ΔNA mutant viruses to access and strip off certain sialic acids that allow the bacteria to establish a foothold. It is important to note that the course of antiviral treatment that was used in mice (twice a day for 5 days) resembles the one recommended by the manufacturer for the treatment of influenza virus infections in humans. This treatment course may be effective at preventing a secondary bacterial infection, depending on the initial influenza virus infective dose.

We observed efficient pulmonary bacterial clearance in naïve mice at 1 dppc after infection with either small or large bacterial inocula (102 to 105 CFU). This initial clearance of pneumococci in naïve mice has been shown to be the result of innate immune responses from alveolar macrophages and neutrophils (18). In our study, the presence of macrophages and neutrophils was observed in mice challenged with pneumococci alone or previously infected with influenza virus. Earlier studies reported that dysfunction of neutrophils and macrophages during influenza virus infection, due to the induction of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and type I IFN, leads to enhanced susceptibility to secondary bacterial infections (25, 31). Influenza virus-induced inflammation of epithelial, bronchial, and alveolar lung cells could provide more attachment sites for bacteria to grow (16). Increased bacterial replication would lead to pneumonia, which could eventually result in death. This is consistent with the histopathological changes observed in human cases during the 1918, 1957, and 1968 pandemics (34). Mice infected with influenza A viruses alone showed mild-to-moderate inflammation at 7 dpi, the time of viral clearance. After a pneumococcal challenge, the inflammation was severe and diffused, involving most of the lobules of the entire lungs of mice in the PR8 and H2N2 virus groups. However, in groups of mice infected with H9N2 viruses, lung inflammation was mild to moderate in some lobes and severe in other lobes, ultimately leading to severe pneumonia and death.

The induction of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines during influenza virus infection is thought to enhance the susceptibility of influenza virus-infected mice to secondary bacterial infections. Several studies have shown that cytokine and chemokine production during primary influenza virus infection can promote both deleterious injury and dysregulation of the recruitment and function of immune cells required for the effective clearance of bacterial pathogens (10, 18, 25, 27, 31). At 8 dpi (1 dppc), the cytokine and chemokine (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, KC, and MIP-1α) levels of mock-infected PBS controls were not significantly different from those of mice infected with S. pneumoniae alone. Increased cytokine/chemokine levels were found at 8 dpi in mice that had received the PR8 virus alone and then a mock challenge with PBS. However, exacerbation of these responses was clearly evident in the virus-infected groups challenge with pneumococci. We found that at 1 dppc, the coinfected mice had significantly higher levels of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, KC, and MIP-1α than the control groups. KC and MIP-1α are chemoattractant molecules that enhance the recruitment of neutrophils and macrophages to the site of inflammation (4). The elevated KC and MIP-1α levels observed in the coinfected mice should have enhanced the recruitment of neutrophils and macrophages and cleared the secondary bacterial infection. However, we observed severe pneumonia and death in these animals, which may have been due to acute inflammatory tissue damage in the lungs caused by these activated leukocytes (33). In contrast, we observed modest increases in IL-10 levels after a bacterial challenge but only in mice that had been previously infected with PR8 or the WT H9N2 virus. Based on our data, the increased lethality of S. pneumoniae infection seen after 7 days of influenza virus infection may be due to dysfunctional alveolar macrophages and neutrophils. The exaggerated cytokine responses seen in our model of secondary bacterial pneumonia are likely responsible for the severity of the disease and the rapid death seen.

In the 20th century, three human influenza pandemics occurred, in 1918 (H1N1), 1957 (H2N2), and 1968 (H3N2), causing significant mortality (34). In April 2009, a novel, swine-derived influenza H1N1 virus (pH1N1) caused the first influenza pandemic of the 21st century. Importantly, during these pandemics, a large proportion of the deaths that occurred were attributable to secondary bacterial respiratory infections. We have previously shown that reassorted viruses carrying the H9N2 virus surface genes in the seasonal human H3N2 and pH1N1 viruses were efficiently transmitted via respiratory droplets in ferrets (9, 30). Also, Sun et al. showed that the reassortants derived from avian H9N2 and pH1N1 viruses were more pathogenic in mice than both parental viruses were (32). In this context, the present study highlights the importance of avian influenza viruses (H2N2 and H9N2) with or without a deletion in the NA gene and its role in the superinfection of mice with S. pneumoniae.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Yonas Araya for assistance with mouse studies and Theresa Wolter Marth for excellent laboratory managerial skills.

This research was made possible through funding by USDA ARS specific cooperative agreement 58-3625-0-611, CSREES USDA grant 1865-05523, and NIAID NIH contract HHSN266186700010C.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 25 January 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Bartlett JG, Mundy LM. 1995. Community-acquired pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 333:1618–1624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Butt KM, et al. 2005. Human infection with an avian H9N2 influenza A virus in Hong Kong in 2003. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:5760–5767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Castrucci MR, Kawaoka Y. 1993. Biologic importance of neuraminidase stalk length in influenza A virus. J. Virol. 67:759–764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chensue SW. 2001. Molecular machinations: chemokine signals in host-pathogen interactions. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14:821–835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Colman PM, Varghese JN, Laver WG. 1983. Structure of the catalytic and antigenic sites in influenza virus neuraminidase. Nature 303:41–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Els MC, Air GM, Murti KG, Webster RG, Laver WG. 1985. An 18-amino acid deletion in an influenza neuraminidase. Virology 142:241–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hoffmann E, Krauss S, Perez D, Webby R, Webster RG. 2002. Eight-plasmid system for rapid generation of influenza virus vaccines. Vaccine 20:3165–3170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hossain MJ, Hickman D, Perez DR. 2008. Evidence of expanded host range and mammalian-associated genetic changes in a duck H9N2 influenza virus following adaptation in quail and chickens. PLoS One 3:e3170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kimble JB, Sorrell E, Shao H, Martin PL, Perez DR. 2011. Compatibility of H9N2 avian influenza surface genes and 2009 pandemic H1N1 internal genes for transmission in the ferret model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:12084–12088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. LeVine AM, Koeningsknecht V, Stark JM. 2001. Decreased pulmonary clearance of Sp following influenza A infection in mice. J. Virol. Methods 94:173–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li KS, et al. 2004. Genesis of a highly pathogenic and potentially pandemic H5N1 influenza virus in eastern Asia. Nature 430:209–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Liu JH, et al. 2004. Interregional transmission of the internal protein genes of H2 influenza virus in migratory ducks from North America to Eurasia. Virus Genes 29:81–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Luo G, Chung J, Palese P. 1993. Alterations of the stalk of the influenza virus neuraminidase: deletions and insertions. Virus Res. 29:141–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Matrosovich M, Zhou N, Kawaoka Y, Webster R. 1999. The surface glycoproteins of H5 influenza viruses isolated from humans, chickens, and wild aquatic birds have distinguishable properties. J. Virol. 73:1146–1155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McCullers JA. 2004. Effect of antiviral treatment on the outcome of secondary bacterial pneumonia after influenza. J. Infect. Dis. 190:519–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McCullers JA. 2006. Insights into the interaction between influenza virus and pneumococcus. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 19:571–582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McCullers JA, Bartmess KC. 2003. Role of neuraminidase in lethal synergism between influenza virus and Sp. J. Infect. Dis. 187:1000–1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McNamee LA, Harmsen AG. 2006. Both influenza-induced neutrophil dysfunction and neutrophil-independent mechanisms contribute to increased susceptibility to a secondary Sp infection. Infect. Immun. 74:6707–6721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Munier S, et al. 2010. A genetically engineered waterfowl influenza virus with a deletion in the stalk of the neuraminidase has increased virulence for chickens. J. Virol. 84:940–952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Peiris JS, et al. 2001. Cocirculation of avian H9N2 and contemporary “human” H3N2 influenza A viruses in pigs in southeastern China: potential for genetic reassortment? J. Virol. 75:9679–9686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Peltola VT, McCullers JA. 2004. Respiratory viruses predisposing to bacterial infections: role of neuraminidase. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 23:S87–S97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Peltola VT, Murti KG, McCullers JA. 2005. Influenza virus neuraminidase contributes to secondary bacterial pneumonia. J. Infect. Dis. 192:249–257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Reed LJ, Muench H. 1938. A simple method of estimating 50 percent endpoints. Am. J. Hyg. 27:493–497 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schäfer JR, et al. 1993. Origin of the pandemic 1957 H2 influenza A virus and the persistence of its possible progenitors in the avian reservoir. Virology 194:781–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shahangian A, et al. 2009. Type I IFNs mediate development of postinfluenza bacterial pneumonia in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 119:1910–1920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Simonsen L, Fukuda K, Schonberger LB, Cox NJ. 2000. The impact of influenza epidemics on hospitalizations. J. Infect. Dis. 181:831–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Smith MW, Schmidt JE, Rehg JE, Orihuela CJ, McCullers JA. 2007. Induction of pro- and anti-inflammatory molecules in a mouse model of pneumococcal pneumonia after influenza. Comp. Med. 57:82–89 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sorrell EM, Perez DR. 2007. Adaptation of influenza A/Mallard/Potsdam/178-4/83 H2N2 virus in Japanese quail leads to infection and transmission in chickens. Avian Dis. 51:264–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sorrell EM, Song H, Pena L, Perez DR. 2010. A 27-amino-acid deletion in the neuraminidase stalk supports replication of an avian H2N2 influenza A virus in the respiratory tract of chickens. J. Virol. 84:11831–11840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sorrell EM, Wan H, Araya Y, Song H, Perez DR. 2009. Minimal molecular constraints for respiratory droplet transmission of an avian-human H9N2 influenza A virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:7565–7570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sun K, Metzger DW. 2008. Inhibition of pulmonary antibacterial defense by interferon-gamma during recovery from influenza infection. Nat. Med. 14:558–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sun Y, et al. 2011. High genetic compatibility and increased pathogenicity of reassortants derived from avian H9N2 and pandemic H1N1/2009 influenza viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:4164–4169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tate MD, et al. 2009. Neutrophils ameliorate lung injury and the development of severe disease during influenza infection. J. Immunol. 183:7441–7450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Taubenberger JK, Morens DM. 2008. The pathology of influenza virus infections. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 3:499–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Thompson WW, et al. 2003. Mortality associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States. JAMA 289:179–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Varghese JN, Laver WG, Colman PM. 1983. Structure of the influenza virus glycoprotein antigen neuraminidase at 2.9 A resolution. Nature 303:35–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wright PF, Thompson J, Karzon DT. 1980. Differing virulence of H1N1 and H3N2 influenza strains. Am. J. Epidemiol. 112:814–819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhou H, et al. 2009. The special neuraminidase stalk-motif responsible for increased virulence and pathogenesis of H5N1 influenza A virus. PLoS One 4:e6277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]