Abstract

Memory/effector T cells efficiently migrate into extralymphoid tissues and sites of infection, providing immunosurveillance and a first line of defense against invading pathogens. Even though it is a potential means to regulate the size, quality, and duration of a tissue infiltrate, T cell egress from infected tissues is poorly understood. Using a mouse model of influenza A virus infection, we found that CD8 effector T cells egressed from the infected lung in a CCR7-dependent manner. In contrast, following antigen recognition, effector CD8 T cell egress decreased and CCR7 function was reduced in vivo and in vitro, indicating that the exit of CD8 T cells from infected tissues is tightly regulated. Our data suggest that the regulation of T cell egress is a mechanism to retain antigen-specific effectors at the site of infection to promote viral clearance, while decreasing the numbers of bystander T cells and preventing overt inflammation.

INTRODUCTION

Memory/effector T cells migrate efficiently into extralymphoid tissues and sites of inflammation and infection (reviewed in reference 10), providing the first line of defense against invading pathogens. Chemoattractants and their receptors are important in this process by navigating T cell migration into extralymphoid organs (36, 40). The lung is an extralymphoid organ that is constantly threatened by airborne pathogens due to its vast exposure to the environment during gas exchange. During an immune response, antigen-specific T cells accumulate at the effector site (46, 54), which is thought to aid pathogen clearance during infection. T cell migration into tissues, including the lung, is independent of the antigen specificity of T cells (1, 20, 49), demonstrating that differential recruitment of antigen-specific T cells is not responsible for their preferential accumulation in infected tissues. Memory/effector CD8 T cells in most extralymphoid tissues, such as the lung, reach equilibrium with newly immigrating CD8 T cells relatively rapidly in parabiotic mouse models (33), suggesting their continuous replacement.

Memory/effector T cells not only efficiently infiltrate extralymphoid tissues and sites of inflammation but also exit these tissues through afferent lymph vessels that lead into the draining lymph node (9). Lymphocytes that egress via lymph from inflamed tissue reenter the circulation and continue their immunosurveillance (12). Similar to entry, exit from extralymphoid tissues via the afferent lymph is tightly regulated, and CD4 and CD8 T cells require the expression of the chemokine receptor CCR7 (8, 14). Congruently, lymphatic endothelial cells of the afferent lymphatics constitutively express the CCR7 ligand CCL21 in many organs (25). In systems studying dendritic cell migration into the afferent lymph, it was shown that the CCL21-CCR7 axis mediates chemotaxis toward and docking to the CCL21+ lymph vessel (50). Importantly, inflammation induces additional chemoattractants in the lymphatics (31), and chronic inflammation promotes CCR7-independent egress of T cells from skin (9). Thus, while CCR7 promotes T cell egress from uninfected extralymphoid tissue, additional or alternative receptors may regulate T cell exit from infected tissue sites. To date, infection-induced T cell egress has been demonstrated for the skin in a model of parasite infection (19) but not for other extralymphoid tissues. Indeed, it remains controversial as to whether or not T cells are able to exit the lung (8, 26, 39). Thus, despite its potential importance in determining the net accumulation of T cells at the effector site, it is currently unknown whether T cells egress from infected tissues other than the skin and which receptors are involved.

Influenza virus infection causes yearly seasonal pandemics with serious worldwide morbidity and mortality. Productive influenza virus infection is limited to epithelial cells of the respiratory tract (32), which can result in pneumonia with severe to fatal respiratory dysfunction (35). Cytotoxic CD8 T lymphocytes (CTLs) play a critical role in influenza virus clearance during primary infection (17) and reinfection with heterotypic strains (41) by cytolysis of infected epithelial cells (55). The recruitment of CTLs into the infected lung occurs throughout infection, resulting in a large CD8 T cell infiltrate (17). Importantly, antigen-specific CTLs are retained in the respiratory tract following clearance of respiratory viruses and are crucial in the defense against reinfection (29, 45). While very late activation antigen 1 (VLA-1; α1β1 integrin) was implicated in this long-term retention of T cells (45), the mechanisms by which retention is achieved are unclear.

T cell egress from the infected lung, by regulating the dwell time in the infected tissue, likely influences local T cell effector function and disease outcome. Here, we found that during acute infection, lymphatic endothelial cells in the lung upregulated the CCR7 ligand CCL21, thereby promoting CCR7-dependent egress of CTL populations from the inflamed site. However, virus-specific CTLs showed reduced exit that was paralleled by downregulation of CCR7 function. Together, our data suggest that upregulation of CCL21 in inflamed tissues supports CCR7-dependent exit of bystander T cells, thereby preventing overt inflammation and enabling immunosurveillance of other sites. Conversely, downregulation of CCR7 on antigen-specific T cells blocks their egress, allowing for their retention at the site of infection to promote viral clearance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and viral infection.

Female BALB/cByJ mice were used for all experiments. BALB/c Ccr7−/− mice (23) were kindly provided by Martin Lipp (Max-Delbrück Center, Berlin, Germany) and further backcrossed for 8 generations onto the Thy1.1 congenic BALB/cByJ background. Age-matched wild-type (WT) Thy1.2+ mice, Thy1.1 congenic mice, and T cell receptor (TCR) transgenic clone-4 (CL-4) mice (42), which recognize the influenza A/PR/8/34 (H1N1)-derived hemagglutinin (HA) peptide512–520, were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). For viral infection, animals were sedated with 2 mg of Dexdomitor (Orion Pharma, New York, NY) per kilogram of body weight and fully anesthetized by isoflurane (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL) inhalation before intranasal infection with a sublethal dose (1,500 × 50% egg infectious dose [EID50]) of the influenza A virus strains A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) (PR8) or influenza A/Aichi/2/68 (H3N2) (X31) in allantoic fluid (Charles River Laboratories, New York, NY) diluted in 30 μl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (total volume per animal). After infection, sedation was reversed with 1 mg/kg Antisedan (Orion Pharma). All animal experiments were approved by and performed according to the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pennsylvania.

Cell isolation.

Lung airway cells were collected through three consecutive bronchoalveolar lavages (BAL) with 1 ml of Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium 1640 (RPMI) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Single-cell suspensions from lung were prepared by a 30-min digest at 37°C with 0.065 U/ml Liberase TM (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) and 0.1 mg/ml DNase I in Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) (Invitrogen). Single-cell suspensions from spleens and mediastinal lymph nodes were prepared in RPMI supplemented with 5% serum (HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT) by passage through 40-μm-pore-size cell strainers (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Single-cell suspensions from lungs, BAL fluids, and spleens were further subjected to red blood cell lysis using red blood cell lysing buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). For pulmonary lymphocyte transfer experiments, lung single-cell suspensions were additionally depleted of macrophages and dendritic cells by 1 h of incubation on plastic dishes (BD Falcon, San Jose, CA) at 37°C.

Cell culture, PTX treatment, cell labeling, and transfer.

To generate Tc1 cells, CD8 T cells were isolated from spleens and lymph nodes of CL-4 or WT mice using anti-CD8 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA), reaching a purity of ≥95%. CD8 T cells (2 × 106 cells/ml) were stimulated on 24-well plates (Corning Costar, Lowell, MA) coated with anti-CD3 (clone 145-c211; eBioscience, San Diego, CA) and anti-CD28 (clone 37.51; eBioscience) antibodies in RPMI containing 10% fetal calf serum, 5 ng/ml recombinant murine interleukin 12 (IL-12) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), 20 ng/ml gamma interferon (IFN-γ) (R&D Systems), and 5 μg/ml anti-IL-4 antibody (clone 11B11; University of California San Francisco; Hybridoma and Monoclonal Antibody Core, San Francisco, CA) and cultured for a total period of 5 days. For pertussis toxin (PTX) treatment, Tc1 cells were incubated for 2 h at 37°C with 200 ng/ml PTX (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) in RPMI with 5% serum. Cell labeling with PKH26 was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Sigma-Aldrich). For 5-(and-6)-carboxy fluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) labeling, cells (1 × 107/ml) were incubated in 0.4 μM CFSE in HBSS containing 25 mM HEPES for 5 min at 37°C. PKH26 and CFSE labeling reactions were stopped by adding serum. The cells were subsequently washed three times using RPMI containing serum followed by one PBS wash. Cell transfer populations were mixed approximately at a 1:1 ratio and 5 × 106 to 10 × 106 cells in 30 μl PBS were transferred i.n. into recipient mice. Single-cell suspensions of the draining mediastinal and nondraining (popliteal and subiliac) lymph nodes, lung, BAL fluid, and spleen were analyzed for transferred cells (identified by fluorescent labels and/or Thy1.1 and Th1.2 congenic markers) at 20 h after transfer unless indicated differently. Total cell numbers were enumerated by flow cytometry using a fixed number of polystyrene beads (Polybead; Polysciences, Warrington, PA), and recovered cell numbers were normalized to the exact ratio in the transfer population. CFSE and PKH26 cell labeling was alternated between groups in repeat experiments.

CTL assay and T cell degranulation assay.

A fluorochrome-based CTL assay was employed as described previously (28). Briefly, Tc1 cells were generated from CL-4 mice and harvested on day 5 of culture, and live cells were purified by Histopaque-1083 gradient centrifugation (Sigma-Aldrich). Total lymphocytes from lymph nodes and spleens of WT mice were used as target cells. Target cells were loaded with influenza HA peptide518–526 or the respiratory syncytial virus-derived peptide127–135 (AnaSpec, Fremont, CA) as target controls and labeled with CFSE or PKH26, respectively. CL-4 Tc1 cells were added in different ratios to HA peptide-loaded target cells and target controls and coincubated for 12 h. Ratios of target cells to target controls were determined by flow cytometry. Specific killing of HA peptide-loaded target cells was calculated as the percentage of change in the ratio of target to target control cells relative to the mean ratio change without effector T cell incubation. Each experiment was carried out with alternating CFSE and PKH26 labeling of target and target control cells.

The T cell degranulation assay was employed as described previously (6). Briefly, Tc1 cells were harvested from culture as described above and added to peptide-loaded splenocytes from naïve mice as target cells in a 1:3 effector-to-target cell (E:T) ratio in the presence of an antibody to CD107 (1D4B; eBiosience) and GolgiStop (BD Biosciences) for degranulation assessment, in RPMI containing 10% fetal calf serum. Target cells were loaded with PR8 or (respiratory syncytial virus [RSV]) peptide as described above and labeled with CFSE for discrimination from Tc1 cells. After 5 h, cocultures were subjected to surface staining for CCR7 or chemotaxis assays. Cocultures for subsequent chemotaxis assays did not contain anti-CD107 antibody or GolgiStop.

Chemotaxis assay.

The basic assay was performed as described previously (16). Cells from Tc1 cultures were preincubated in RPMI with 0.5% bovine serum albumin for 1 h. Tc1 cells from degranulation assays or pulmonary cell isolates were added directly into 24-well Transwell permeable supports (5-μm polycarbonate membrane; Corning Costar). The cells were allowed to migrate for 90 min at 37°C to various titrations of recombinant mouse CCL21 (R&D Systems) or medium in triplicate wells. The migration of the different subsets was distinguished by flow cytometry based on the CFSE label and congenic marker (Thy1.1/Thy1.12) expression. Fluoresbrite yellow green microspheres (Polysciences, Warrington, PA) were used as an internal standard to quantify the number of migrated cells.

Flow cytometry.

Cells were preincubated in anti-CD16/CD32 antibodies (clone 2.4G2; BD Pharmingen) and rat or donkey IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA). CD8 (clone 53-6.7), CD4 (clone RM4-5), and Thy1.1 (clone HIS51) rat anti-mouse monoclonal antibodies (eBioscience) were used to recognize surface markers. Binding of mouse CCL19 fused to human IgG (eBioscience) was used to stain for CCR7 as described previously (15). Human immunoglobulin G was used as a control. To detect intracellular cytokines, Tc1 cell cultures were depleted of dead cells by Histopaque-1083 gradient centrifugation prior to polyclonal stimulation with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate and ionomycin and intracellular staining as described previously (16). Samples were acquired on a BD LSRII or Calibur using Diva or CellQuest software (BD Bioscience), respectively, and analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR). Gates were set according to appropriate isotype control staining.

Immunofluorescence.

Tissue sections were prepared from naive lungs or from lungs on day 5 postinfection with PR8, after perfusion with 1% paraformaldehyde and inflation with a 1:1 mix of Tissue-Tek OCT compound (Sakura Finetek USA Inc., Torrance, CA) and PBS, followed by snap-freezing. Thin sections (7 μm) were fixed with 25% ethanol in acetone and rehydrated with 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, treated with 0.25% NH3 in 70% ethanol, blocked with 0.1% donkey serum in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) with 0.05% Tween 20, and subsequently stained with rat-anti mouse LYVE-1 (clone 223322; R&D Systems) and goat-anti-mouse CCL21 (R&D Systems). Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated donkey anti-rat antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch) and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated donkey anti-goat antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch) were used as secondary reagents. Isotype control staining did not yield significant background staining. Slides were embedded in ProLong antifade (Invitrogen). Pictures were acquired on a Nikon E600 fluorescence microscope with a Roper Scientific charge-coupled-device (CCD) camera and NIS Elements BR 3.00 software (Nikon Instruments, Inc., Melville, NY).

Statistical testing.

Chemotaxis assays were analyzed with the paired t test. For all other analyses, the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test and, for paired analyses, the Wilcoxon test were used. GraphPad Prism (La Jolla, CA) software was employed for the combined analysis of all experiments, and P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

CD8 effector T cells exit the lung during acute infection with influenza A virus.

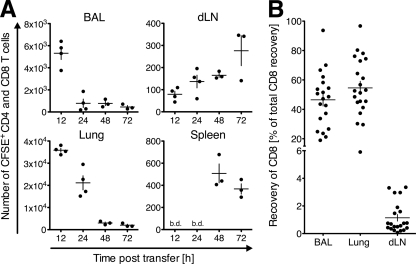

The inflammatory response to infection with influenza virus is characterized by massive T cell infiltration of the lung (58). While T cell exit from the inflamed site could influence the size, quality, and duration of the lung infiltrate, it remains controversial if T cells that have entered the lung airways during infection or inflammation have the ability to subsequently exit this organ (8, 21). To address this, we tested the capacity of pulmonary lymphocytes to exit the lung via the afferent lymph during influenza virus infection. Total lymphocytes were isolated from the lungs of Thy1.1 mice on day 5 postinfection with the influenza virus strain PR8, a time point when T cells start accumulating and viral titers are high (53, 57) but the numbers of virus-specific CD8 T cells in the lung are still low (<1%) (5, 22, 54). After labeling with the fluorescent dye CFSE, these pulmonary lymphocytes were intranasally (i.n.) transferred into congenic Thy1.2 mice that were infected with PR8 5 days prior to the experiment. At different time points after transfer, lymphocytes were reisolated from the airspaces (by BAL), lung, lung-draining mediastinal and nondraining lymph nodes, and the spleen and analyzed for the presence of transferred (CFSE+ Thy1.1+ CD8+ or CD4+) T cells. While the first transferred T cells reached the draining lymph nodes as early as 12 h after instillation, most pulmonary T cells were detected in the draining lymph nodes ≥48 h after transfer (Fig. 1A). Importantly, transferred T cells started appearing in the spleen, a nondraining site that can be reached only via blood circulation, at 48 h posttransfer. The sequential appearance of transferred T cells at draining and then nondraining sites indicated lymphocyte egress from lung via the afferent lymph and migration into the draining lymph nodes before T cells reentered the blood circulation via the efferent lymph. At all time points analyzed, transferred lymphocytes were below the detection limit in nondraining lymph nodes, such as the popliteal and subiliac nodes (not depicted). Based on the lack of lymphocyte recirculation at 24 h after cell transfer (Fig. 1A), cells were reisolated at 20 h posttransfer in all further experiments. Within the analyzed time frame (up to 72 h after cell transfer), no cell proliferation was detected, as indicated by a lack of CFSE dilution among transferred Thy1.1+ cells (data not shown).

Fig 1.

CD8 T cells infiltrating the lung during infection with influenza virus egress from the inflammation site via the draining lymph. On day 5 of infection with PR8, total pulmonary lymphocytes from Thy1.1+ WT mice were isolated and labeled with CFSE and i.n. transferred into PR8-infected (day 5) Thy1.2+ WT recipients. (A) The numbers of CFSE+ Thy1.1+ (CD4+ or CD8+) T cells in the indicated organs were quantified by flow cytometry at different time points posttransfer. One out of two similar experiments with 3 or 4 recipient animals per group is shown. (B) Recovery of Thy1.1+ CFSE+ CD8 T cells from BAL fluid, lung, and draining lymph nodes (dLN) relative to total recovery of Thy1.1+ CFSE+ CD8 T cells at all analyzed sites 20 h after intranasal transfer. All experiments combined (n = 5), analyzing 3 to 5 animals each, are depicted. Data points indicate individual recipient mice, and the mean ± SD of each group is shown. b.d., below detection (10 donor cells).

To confirm the egress of pulmonary CD8 T cells from influenza virus-infected lungs, we repeated the experiments separately analyzing CD8 T cells (Fig. 1B). Similar frequencies of transferred pulmonary CD8 T cells distributed to the airspaces (BAL fluid) and lung parenchyma (Fig. 1B), while a small but consistent proportion of CD8 T cells (1.14 ± 1.1%, mean ± standard deviation [SD]) exited the lung and migrated to the draining lymph node within the 20-h window (Fig. 1B). The results show that pulmonary lymphocytes, including CD8 T cells, egress from the lung during an acute respiratory virus infection.

Tc1 cells exit from the lung during influenza virus infection.

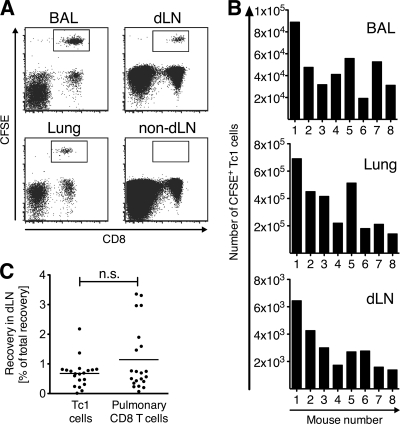

During influenza, the predominant phenotype of CD8 T cells infiltrating the lung is that of IFN-γ+ Tc1 cells (17). We next asked if Tc1 cells have the capacity to exit the lungs of influenza virus-infected mice. In vitro-polarized WT polyclonal Tc1 cells were labeled with CFSE and transferred i.n. into recipient animals that were infected with PR8 5 days prior to the cell transfer. Twenty hours later, transferred Tc1 cells could be recovered from lung and BAL fluid (Fig. 2A and B). In addition, a population of Tc1 cells consistently reached the lymph nodes draining the lung but not the nondraining lymph nodes (Fig. 2A and B). Importantly, in vitro-activated polyclonal Tc1 cells and pulmonary CD8 T cells with heterogeneous activation history and influenza virus specificity of less than 1% (5, 22, 54) exit the infected lung with similar capacities (Fig. 2C). Together, the data show that CD8 effector T cells egress from the lung during active influenza virus infection, indicating that regulated egress could potentially contribute to the size, quality, and duration of the T cell response in the lung infiltrate.

Fig 2.

Tc1 cells exit from the lung during acute influenza A virus infection. WT CFSE-labeled Tc1 cells were i.n. transferred into mice on day 5 of infection with PR8. Twenty hours after transfer, BAL fluid, lung, and draining lymph nodes (dLN) and nondraining lymph nodes (non-dLN) were analyzed by flow cytometry (A), and numbers of recovered CFSE+ Tc1 cells were enumerated in individual recipient mice (B). One representative staining (A) and experiment (B) out of 5 performed experiments, analyzing 5 to 10 recipient mice each, is shown. (C) The relative cell recovery in draining lymph nodes relative to total recovery in all organs was analyzed for CFSE+ Tc1 cells and CFSE+-infected lung-derived CD8 T cells that were transferred i.n. into PR8-infected recipient mice. The pooled analysis of all experiments is shown.

Virus-specific effector T cells exhibit reduced lung exit capacity.

Having established that polyclonal effector T cells egress from the influenza virus-infected lung (Fig. 1 and 2), we next asked whether virus-specific CD8 T cells also egress from the lung during an ongoing infection with influenza virus. To address this, we generated Tc1 cells from TCR transgenic CL-4 mice (42), which recognize the PR8-derived hemagglutinin (HA) peptide518–526 and protect naïve recipient mice from lethal infection with PR8 (11) (data not shown). In parallel, we generated Tc1 cells from WT mice using the same activation protocol. In our hands, CL-4 and WT Tc1 cells produced high levels of IFN-γ upon restimulation (Fig. 3A) (data not shown), and CL-4 Tc1 cells possessed specific killing activity of HA peptide518–526-loaded target cells in vitro (Fig. 3B). Thus, CL-4 Tc1 cells were functional PR8-specific effector T cells. We utilized a competitive cell transfer system that allows for comparison of the migratory capacity of CL-4 and WT Tc1 cells. Twenty hours after transfer into recipient mice infected with X31, an influenza A virus strain not recognized by the CL-4 TCR, roughly equal numbers of polyclonal (WT) and CL-4 Tc1 cells were found at the cell instillation sites (BAL fluid and lung) and the draining lymph nodes (Fig. 3C), indicating that Tc1 cells on both backgrounds have the same capacity to exit from the lung. In contrast, after i.n. transfer into PR8-infected recipients, CL-4 Tc1 cells reached the draining lymph nodes in significantly reduced numbers compared with polyclonal Tc1 cells (P = 0.0002; Fig. 3D). Following transfer into X31- or PR8-infected mice, only few if any WT or CL-4 Tc1 cells were found at distant sites, such as the spleen. These results suggests that upon recognition of virus, CD8 effector T cells downregulate their “tissue exit program” and are retained at the effector site, while antigen-nonspecific bystander T cells continue to egress from the infected lung.

Fig 3.

Virus-specific CD8 effector T cells show impaired exit from the influenza virus-infected lung. (A and B) In vitro-generated Tc1 cells were tested for immediate effector functions. (A) Intracellular IFN-γ staining following polyclonal restimulation. (B) The potential of CL-4 Tc1 cells to specifically lyse fluorescently labeled HA peptide518–526-loaded target cells in vitro was assessed at the indicated ratios of effector (E) to target (T) cells. One of two similar experiments is shown. Data points indicate means ± SD from five wells per E:T ratio. (C and D) Intranasal cotransfer of CFSE-labeled WT (Thy1.2+) and CL-4 (Thy1.1+) Tc1 cells into recipient mice on day 5 postinfection with influenza virus strain X31 (C) or PR8 (D). Twenty hours after transfer, CFSE+ donor Tc1 cells were enumerated in BAL fluid, lung, and draining lymph nodes (dLN) by flow cytometry. Results were normalized to the transferred ratio of Thy1.2+ to Thy1.1+ T cells. For each infection, one representative out of three performed experiments using 7 to 9 recipient mice each is shown.

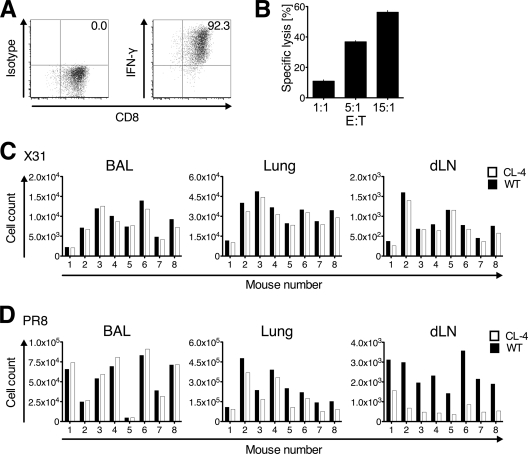

Lung exit of effector CD8 T cells during influenza A virus infection is an active process.

The appearance of CD8 effector T cells in the lung-draining lymph nodes after their transfer into the airways of influenza virus-infected mice (Fig. 1 to 3) could be promoted by either regulated migration or more passive mechanisms, e.g., increased fluid flux during inflammation promoting the “overflow” of donor cells. To determine if T cell egress was a regulated process, we assessed its requirement for Gαi-coupled receptors, through which most chemokine receptors signal, by employing pertussis toxin (PTX) treatment. PTX irreversibly modifies Gαi-coupled receptors, rendering them unresponsive to subsequent stimulation. WT Tc1 cells were incubated with PTX, labeled with CFSE, and i.n. transferred into recipient mice on day 5 postinfection with PR8 (Fig. 4). A separate group of infected control recipients received mock-treated CFSE-labeled Tc1 cells. Recipients were analyzed 20 h posttransfer for the presence of transferred cells in BAL fluid and lungs as well as draining and nondraining lymph nodes (Fig. 4). The total recovery of transferred cells (all organ sites combined) was similar for both recipient groups (Fig. 4A), demonstrating that PTX did not negatively impact the transfer efficiency or cell survival during the course of the experiment. In contrast, while PTX-treated and mock-treated Tc1 cells entered the airspaces and lung parenchyma equally well after intranasal transfer, PTX treatment completely abrogated T cell migration into the draining lymph nodes (Fig. 4B). No PTX-treated cells were detected at distant sites (data not shown). These results show that T cell migration from the infected lung to the draining lymph nodes is PTX sensitive, confirming that T cell exit from the influenza virus-infected lung is an active and regulated process that likely requires (Gαi) chemoattractant receptor signaling.

Fig 4.

Lung exit of Tc1 cells during acute influenza A virus infection requires Gαi protein-coupled receptor signaling. CFSE-labeled WT Tc1 cells, treated with PTX or mock treated (Control), were transferred i.n. into separate groups of recipient mice on day 5 of infection with PR8. Twenty hours after transfer, BAL fluid, lung, and draining lymph nodes (dLN) were analyzed for transferred cells by flow cytometry. (A) Total recovery of CFSE+ Tc1 cells from BAL fluid, lung, and draining lymph nodes as percentage of transferred cells per animal; (B) cell counts for recovered CFSE+ PTX-treated or mock-treated cells from BAL fluid, lung, and draining lymph nodes. One representative experiment of three performed analyzing 6 or 7 mice each is shown. Data points represent individually analyzed recipient mice, and the mean ± SD of each group is indicated.

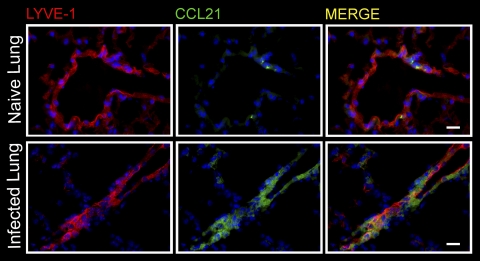

Lymphatic endothelial cells in the influenza virus-infected lung upregulate CCL21.

Having determined a likely role for chemoattractants in effector CD8 T cell exit from the influenza virus-infected lung (Fig. 4), we next determined expression of the CCR7 ligand CCL21 by lymphatic endothelial cells in the lung. In naïve mice, CCL21 expression by pulmonary lymphatic endothelial cells, identified by expression of the lymphatic endothelial cell-specific marker LYVE-1+ (3), was limited to small punctiform areas (Fig. 5, top). Thus, CCL21 expression patterns in afferent lymphatics within the lung resemble those previously described for the skin (50, 56) in which the CCL21+ area marks the entry port into the vessel (50). In contrast, following infection with influenza virus, CCL21 expression was more abundant, with a wide distribution within pulmonary lymphatic endothelial cells (Fig. 5, bottom). The results show that pulmonary afferent lymph vessels upregulate CCL21 following influenza virus infection. Thus, CCL21 is well positioned to support the egress of CCR7+ T cells from the infected lung via the afferent lymph.

Fig 5.

Lymphatic endothelial cells in the lung upregulate CCL21 during infection with influenza virus. Immunofluorescence staining of frozen lung sections of naïve mice or on day 5 of infection with PR8. Images were acquired on a Nikon fluorescence microscope using a 40× objective. DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) in blue; scale bar, 20 μm. One representative image of three analyzed mice per group is shown.

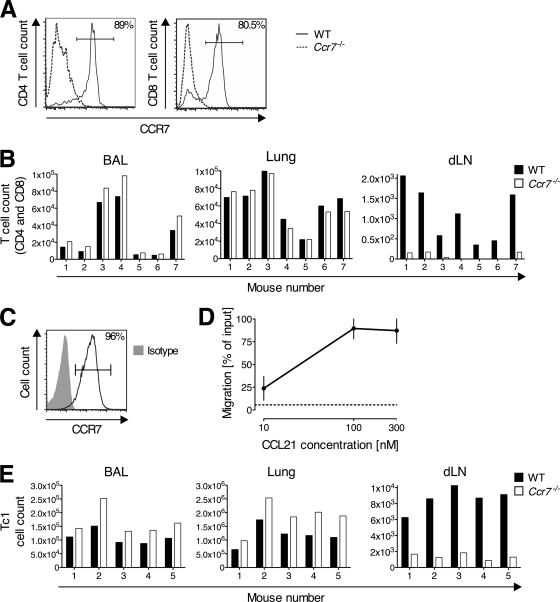

Lung exit of effector CD8 T cells is mediated by the chemokine receptor CCR7.

CCL21 upregulation by afferent lymph vessels within the lungs of influenza virus-infected mice (Fig. 5) prompted us to investigate the role of CCR7 in lung exit of T cells during infection. During influenza virus infection, the majority of lung-infiltrating CD4 and CD8 T cells were CCR7+ in WT mice (Fig. 6A). To test for a role of CCR7 in the migration of pulmonary T cells from the infected lung into the draining lymph nodes via the afferent lymph, we isolated lung-infiltrating lymphocytes from Thy1.2+ WT and Thy1.1+ Ccr7-deficient mice (Ccr7−/−) on day 5 of infection with PR8. After labeling with CFSE, equal numbers of the donor cell types were cotransferred i.n. into influenza virus-infected Thy1.2+ or Thy1.1+/Thy1.2+ WT recipients. Twenty hours after transfer, Ccr7−/− T cells (CD4 and CD8) slightly accumulated in the respiratory tract compared with WT T cells (P = 0.0007, combined analysis of BAL fluid and lung; Fig. 6B). Congruently, the number of Ccr7−/− T cells (CD4 and CD8) that migrated to the draining lymph nodes was significantly decreased relative to that of the WT (P = 0.0005; Fig. 6B). Within the time frame studied, cell proliferation was negligible (based on a lack of CFSE dilution among transferred Thy1.1+ and Th1.2+ cells (data not shown). Next, we repeated the experiments with in vitro-generated Tc1 cells, which, like most CD8 T cells in the lung infiltrate, expressed CCR7 on the cell surface and migrated toward CCL21 (Fig. 6C and D). Twenty hours after i.n. transfer of CFSE-labeled Ccr7−/− cells and PKH26-labeled WT Tc1 cells, Ccr7−/− Tc1 cells accumulated in the airspaces and lung relative to WT cells (P = 0.0001; Fig. 6E). In contrast, the number of Ccr7−/− Tc1 cells that migrated to the draining lymph nodes was significantly decreased (P = 0.0005; Fig. 6E). Following transfer of pulmonary T cells or Tc1 cells, at 20 h, donor cells were undetectable in nondraining sites (i.e., popliteal lymph nodes and spleen) (data not shown). These data demonstrate a requirement for CCR7 in the lymphatic exit of T cells from the lung during acute influenza virus infection.

Fig 6.

CD8 effector T cells require CCR7 to exit from the lung during influenza virus infection. (A and B) Thy1.2+ WT and Thy1.1+ Ccr7−/− mice were infected with PR8. On day 5 of infection, CCR7 expression on CD4 and CD8 T cells from BAL fluid and lung parenchyma was determined by flow cytometry (A), and pulmonary lymphocytes from both groups were mixed and labeled with CFSE before i.n. transfer into PR8-infected (day 5) WT recipients (B). Twenty hours after transfer, donor CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were enumerated in BAL fluid, lung, and draining lymph nodes (dLN) by flow cytometry. Results were normalized to the pretransfer ratio of Thy1.2+ to Thy1.1+ for each T cell subset. One representative of three performed experiments is shown analyzing pooled cells from 8 to 15 donors per group (A) and 4 to 8 recipient mice per experiment (B). WT Tc1 cells were generated and on day 5 of culture, CCR7 expression was determined by flow cytometry (C) and migration toward CCL21 tested in a Transwell chemotaxis assay (D). Chemotaxis is shown as the percentage of input cells that migrated to the lower chamber. Data points represent the means ± SD of results from three independent experiments. The dotted line indicates migration to medium alone. (E) PKH26-labeled WT and CFSE-labeled Ccr7−/− Tc1 cells were mixed and cotransferred i.n. into recipient mice on day 5 of infection with PR8. Twenty hours after transfer, BAL fluid, lung, and draining lymph nodes (dLN) were analyzed for transferred cells. Results were normalized to the transferred ratio of CFSE+ to PKH26+ cells. One representative out of three performed experiments, using 4 to 8 recipient animals each, is shown.

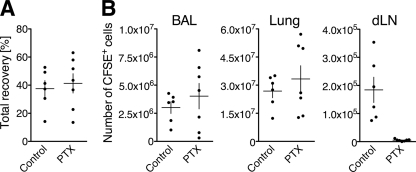

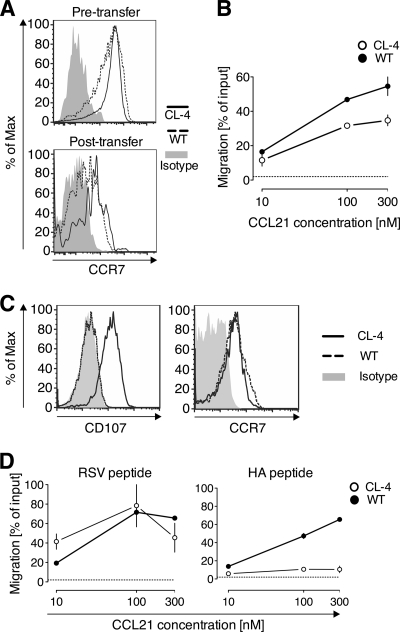

Antigen recognition by Tc1 cells reduces their responsiveness to CCL21.

The reduced lung exit capacity of virus-specific Tc1 cells (Fig. 3), together with the requirement for CCR7 to egress from the influenza virus-infected lung (Fig. 6), raised the question of whether antigen recognition leads to downregulation of CCR7 expression and/or function in memory/effector CD8 T cells. To address this, we transferred both antigen-specific CL-4 and WT Tc1 cells into PR8-infected mice and reisolated them 40 h later. While both CL-4 and WT Tc1 cells showed decreased levels of CCR7 after reisolation from the infected lungs relative to the input (pretransfer) Tc1 cells, no obvious difference in CCR7 expression was noted between reisolated (posttransfer) WT and CL-4 Tc1 cells (Fig. 7A), suggesting that retention of antigen-specific T cells was not dependent on preferential downregulation of CCR7 surface expression. However, when the function of CCR7 was assessed in an in vitro chemotaxis assay, CL-4 Tc1 cells were significantly impaired in their responsiveness to CCL21 relative to WT Tc1 cells (P = 0.0039 for responses to 100 nM; Fig. 7B). These data suggest that exposure to the inflamed lung environment induces downregulation of CCR7, while antigen recognition leads to impairment of CCR7 function.

Fig 7.

Antigen recognition by CD8 effector T cells reduces their chemotaxis toward CCL21. CFSE-labeled Thy1.2+ WT and Thy1.1+ CL-4 Tc1 cells were cotransferred i.n. into Thy1.2+ recipient mice on day 5 of infection with PR8. Forty hours posttransfer, cells were reisolated, and CCR7 expression was determined by flow cytometry (A), and migration toward CCL21 was tested in a Transwell chemotaxis assay (B). Chemotaxis is shown as the percentage of input cells of the indicated cell subset that migrated to the lower chamber. Data points represent means ± SD of results from triplicate wells. The dotted line indicates migration to medium alone. (C) CL-4 and WT Tc1 cells were incubated with HA peptide518–526-loaded target cells, and degranulation was determined by CD107 staining and compared to CCR7 expression by flow cytometry. (D) CL-4 and WT Tc1 cells were incubated with HA peptide518–526- or control peptide (RSV127–135)-loaded target cells for 5 h prior to testing migration toward CCL21 in a Transwell chemotaxis assay. Chemotaxis is expressed as the percentage of input cells of the indicated cell subset that migrated to the lower chamber. Data points represent means ± SD of triplicate wells. The dotted line indicates migration to medium alone. One representative of at least three independent experiments is shown.

As our in vivo approach was unable to distinguish between T cells that did and did not encounter antigen, we aimed to further dissect the effect of antigen recognition on functional CCR7 expression by effector CD8 T cells. To accomplish this, we stimulated WT and CL-4 Tc1 cells with antigen-loaded target cells for 5 h in vitro and subsequently determined T cell surface expression of CD107, which visualizes recent TCR-triggered CTL degranulation (6). CD107 expression by virtually all CL-4 Tc1 cells confirmed their TCR activation and cytolytic activity following stimulation with HA-loaded target cells (Fig. 7C). In contrast, WT Tc1 cells were CD107− (Fig. 7C). Similar to our in vivo results (Fig. 7A), there was no difference between WT and CL-4 Tc1 cells in CCR7 surface expression (Fig. 7C). Moreover, consistent with our in vivo results, exposure of CL-4 Tc1 cells to target cells loaded with their cognate antigen (HA peptide), but not to control peptide (RSV peptide)-loaded target cells, abrogated their responsiveness to the CCR7 ligand CCL21 (Fig. 7D). The results indicate that antigen recognition by effector CD8 T cells downregulates the function of the exit receptor CCR7 and may therefore promote the retention of antigen-specific T cells at sites of infection.

DISCUSSION

Effector/memory T cells recirculate between blood and extralymphoid tissues, entering from the blood and leaving via the afferent lymph. Mechanisms of T cell migration into tissues are well studied and proven key to host defense. Even though T cell egress from infected tissues likely contributes to the magnitude of the T cell infiltrate and its associated effector functions, mechanisms that regulate T cell egress from infected tissues are not known. In this study, we found that during acute infection with influenza virus, pulmonary lymphatic endothelial cells upregulate the CCR7 ligand CCL21, thereby driving CCR7-dependent lymphatic egress of CTLs from the infected lung.

Although migration into tissues, including the lung, is independent of the antigen specificity of T cells (1, 20, 49), antigen-specific CTLs accumulate in the influenza virus-infected respiratory tract (22, 54). In this study, we show that virus-specific CTL exit from the lung is impaired during infection (Fig. 3), which is paralleled by a reduced migratory response toward CCL21 relative to that of virus-nonspecific CTLs (Fig. 7). CTLs arising from previous immune responses to unrelated pathogens are also recruited to the lungs following influenza infection (54). The egress of these so-called bystander T cells returns the cells to the general circulation and ensures that they are not sequestered and can instead continue to survey other sites for infection, including other areas of the respiratory tract. Such a mechanism of “T cell recycling” efficiently enables the protection of multiple body sites against multiple pathogens during an ongoing infection. In support of this notion, Hay and colleagues demonstrated that lymphocytes egressing from inflamed skin, once they reach the circulation, reenter different tissues (12). In addition, decreasing the numbers of recruited bystander CTLs, by limiting the inflammatory infiltrate, also reduces the potential for detrimental proinflammatory responses. In contrast, virus-specific CTLs that arrive in the infected tissue, whose exit program is downregulated upon antigenic stimulation, will be retained, enhancing host defense against the ongoing infection.

Once virus is cleared and the antigen load reduced, virus-specific T cells that are sequestered in the lung might exit in a CCR7-dependent manner or through the use of alternative exit receptors (9) to become part of the circulating memory pool. However, most virus-specific CTLs will die during the contraction phase either in the lung or after exit and redistribution to the liver, the “graveyard” for T cells (4, 30). A small population of virus-specific pulmonary CTLs follows a different fate and is retained within the lung following viral clearance and is crucial in the protection against reinfection with the same or heterologous influenza virus (45). A similar “sessile” population of CD8 T cells also exists in the skin following herpes simplex virus infection (24). In the case of the lung, it was shown that the adhesion molecule VLA-1 is key to the sequestration of T cells (45). Based on these findings, we propose that the long-term retention of T cells in the lung and airways requires both the downregulation of the expression or function of exit receptors, such as CCR7, and induction of a retention program involving adhesion molecules, such as VLA-1.

The chemokine-regulated positioning within infected tissues influences effector versus memory T cell fate decisions. Specifically, the chemokine receptors CCR5 and CXCR3 mediate CTL colocalization with infected target cells within the lung, thereby ensuring antigenic activation and subsequent contraction of virus-specific CTLs (34). In contrast, CXCR3 deficiency, by localizing the antigen-experienced T cells to the parenchyma, away from infected target cells, leads to decreased antigen encounter within the infected lung and attenuated contraction with increased memory T cell development (34, 37). Similarly, CCR7-driven egress of antigen-experienced CD8 T cells from the infected lung, by decreasing potential interactions with target cells, could also support memory T cell differentiation. In support of this idea, CCR7-deficient animals show impaired CD8 T cell memory formation following infection with influenza virus (27).

T cells in tissues migrate along chemotactic gradients until they encounter antigen on an antigen-presenting cell, which leads to their ICAM-1-dependent arrest by TCR-mediated “stop signals.” “Go signals” delivered by certain chemokines, such as CCL21 or CXCR3 ligands, can override the TCR-mediated stop signal in vitro (7). The result of the competition between stop and go signals influences the duration and strength of T cell-APC interaction and subsequent T cell fate (18). Importantly, the capacity of CCL21 to dislodge arrested T cells is inversely correlated to the antigen dose (18). Moreover, a recent study showed that prolonged TCR stimulation leads to downregulation of CCR7 function, while short-term TCR triggering enhances migration to CCL21 (48). Notably, our studies show that antigen recognition by effector CD8 T cells in the influenza virus-infected lung leads to reduced responsiveness to CCL21 (Fig. 7). These data suggest that the TCR signal received in the infected lung during times of high viral loads is of sufficient strength to desensitize the CCL21 go signal, likely ensuring effective cytolytic interaction with the target cell. However, we observed that not all of the virus-specific Tc1 cells lose their CCL21 responsiveness in the infected lung (Fig. 7B), suggesting that some T cells do not have sufficient contact with the infected respiratory epithelium during our short-term (40-h) adoptive transfer experiment. In addition, it is possible that other types of antigen-specific T cells differ from our TCR transgenic Tc1 cells in their response to antigen encounter in the infected lung.

In further support that antigen recognition by T cells in tissues leads to downregulation of CCR7 expression or function, previous studies show that while most infiltrating CD4 T cells are responsive to CCL21 (15), influenza virus-specific CD4 T cells in the infected lung are CCR7− (15, 47). In addition, Arnold and colleagues demonstrated that naïve CD4 T cells transiently reduce responsiveness to CCR7 ligands following antigen recognition in lymph nodes (2). Interestingly, in our experiments, the differences in CCL21 responsiveness between virus-specific and nonspecific T cells were not dictated by differential changes in surface CCR7 expression (Fig. 7A and C). However, the dissociation of chemokine receptor expression and function is not uncommon (51) and may be related to differences in coupling of CCR7 to downstream signaling molecules. Furthermore, cross talk between TCR and chemokine receptor signaling pathways via the tyrosine kinase ZAP-70 and its substrate LAT has been demonstrated for CCR7 as well as CXCR4, CXCR3, and receptors for CCL5 (13, 44, 48, 52).

Finally, the relative capacity of T cells to exit inflamed tissues potentially impacts the course of infection by regulating the tissue residence time of CD8 effector T cells, thereby affecting local effector functions, such as cytokine production and cytolysis. Besides their protective function, CD8 T cells mediate immunopathology during influenza virus infection (38). Specifically, CD8 T cells confer protection or exacerbate pathology depending on the infectious dose relative to the magnitude of the CTL response (43). Thus, regulation of CD8 T cell egress from the infected lung is possibly involved in maintaining the balance of viral load and the numbers of tissue CTLs that are necessary for viral clearance while minimizing the risk for T cell-driven tissue damage. In conclusion, our study reveals effector T cell egress from the infection site and antigen-driven retention as novel control points of the magnitude and quality of the T cell infiltrate during influenza virus infection, with relevance for the pathogenesis of influenza and other infectious diseases. Furthermore, the regulation of tissue exit provides a new therapeutic target to augment or ameliorate T cell-mediated effector responses in extralymphoid tissues.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grant AI073682 to G.F.D. and the postdoctoral fellowship 10PPOST3650023 by the American Heart Association to S.J.

We thank Dan Campbell, Chris Hunter, Carolina Lopez, Skye Geherin, and Leslie King for critical readings of the manuscript and Florian Simon for technical assistance.

We have no conflicting financial interests.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 25 January 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Ager A, Drayson MT. 1988. Lymphocyte migration in the rat, p 19–49 In Husband AJ. (ed), Migration and homing of lymphoid cells. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arnold CN, Butcher EC, Campbell DJ. 2004. Antigen-specific lymphocyte sequestration in lymphoid organs: lack of essential roles for alphaL and alpha4 integrin-dependent adhesion or Galphai protein-coupled receptor signaling. J. Immunol. 173:866–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Banerji S, et al. 1999. LYVE-1, a new homologue of the CD44 glycoprotein, is a lymph-specific receptor for hyaluronan. J. Cell Biol. 144:789–801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Belz GT, Altman JD, Doherty PC. 1998. Characteristics of virus-specific CD8(+) T cells in the liver during the control and resolution phases of influenza pneumonia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95:13812–13817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Belz GT, Xie W, Altman JD, Doherty PC. 2000. A previously unrecognized H-2D(b)-restricted peptide prominent in the primary influenza A virus-specific CD8(+) T-cell response is much less apparent following secondary challenge. J. Virol. 74:3486–3493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Betts MR, et al. 2003. Sensitive and viable identification of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells by a flow cytometric assay for degranulation. J. Immunol. Methods 281:65–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bromley SK, Peterson DA, Gunn MD, Dustin ML. 2000. Cutting edge: hierarchy of chemokine receptor and TCR signals regulating T cell migration and proliferation. J. Immunol. 165:15–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bromley SK, Thomas SY, Luster AD. 2005. Chemokine receptor CCR7 guides T cell exit from peripheral tissues and entry into afferent lymphatics. Nat. Immunol. 6:895–901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brown MN, et al. 2010. Chemoattractant receptors and lymphocyte egress from extralymphoid tissue: changing requirements during the course of inflammation. J. Immunol. 185:4873–4882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Campbell DJ, Debes GF, Johnston B, Wilson E, Butcher EC. 2003. Targeting T cell responses by selective chemokine receptor expression. Semin. Immunol. 15:277–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cerwenka A, Morgan TM, Dutton RW. 1999. Naive, effector, and memory CD8 T cells in protection against pulmonary influenza virus infection: homing properties rather than initial frequencies are crucial. J. Immunol. 163:5535–5543 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chin W, Hay JB. 1980. A comparison of lymphocyte migration through intestinal lymph nodes, subcutaneous lymph nodes, and chronic inflammatory sites of sheep. Gastroenterology 79:1231–1242 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dar WA, Knechtle SJ. 2007. CXCR3-mediated T-cell chemotaxis involves ZAP-70 and is regulated by signalling through the T-cell receptor. Immunology 120:467–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Debes GF, et al. 2005. Chemokine receptor CCR7 required for T lymphocyte exit from peripheral tissues. Nat. Immunol. 6:889–894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Debes GF, et al. 2004. CC chemokine receptor 7 expression by effector/memory CD4+ T cells depends on antigen specificity and tissue localization during influenza A virus infection. J. Virol. 78:7528–7535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Debes GF, et al. 2006. Chemotactic responses of IL-4-, IL-10-, and IFN-gamma-producing CD4+ T cells depend on tissue origin and microbial stimulus. J. Immunol. 176:557–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Doherty PC, et al. 1997. Effector CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell mechanisms in the control of respiratory virus infections. Immunol. Rev. 159:105–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dustin ML. 2004. Stop and go traffic to tune T cell responses. Immunity 21:305–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Egan PJ, et al. 1996. Inflammation-induced changes in the phenotype and cytokine profile of cells migrating through skin and afferent lymph. Immunology 89:539–546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ely KH, et al. 2003. Nonspecific recruitment of memory CD8+ T cells to the lung airways during respiratory virus infections. J. Immunol. 170:1423–1429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ely KH, Cookenham T, Roberts AD, Woodland DL. 2006. Memory T cell populations in the lung airways are maintained by continual recruitment. J. Immunol. 176:537–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Flynn KJ, et al. 1998. Virus-specific CD8+ T cells in primary and secondary influenza pneumonia. Immunity 8:683–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Forster R, et al. 1999. CCR7 coordinates the primary immune response by establishing functional microenvironments in secondary lymphoid organs. Cell 99:23–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gebhardt T, et al. 2009. Memory T cells in nonlymphoid tissue that provide enhanced local immunity during infection with herpes simplex virus. Nat. Immunol. 10:524–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gunn MD, et al. 1998. A chemokine expressed in lymphoid high endothelial venules promotes the adhesion and chemotaxis of naive T lymphocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95:258–263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Harris NL, Watt V, Ronchese F, Le Gros G. 2002. Differential T cell function and fate in lymph node and nonlymphoid tissues. J. Exp. Med. 195:317–326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Heer AK, Harris NL, Kopf M, Marsland BJ. 2008. CD4+ and CD8+ T cells exhibit differential requirements for CCR7-mediated antigen transport during influenza infection. J. Immunol. 181:6984–6994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hermans IF, et al. 2004. The VITAL assay: a versatile fluorometric technique for assessing CTL- and NKT-mediated cytotoxicity against multiple targets in vitro and in vivo. J. Immunol. Methods 285:25–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hogan RJ, et al. 2001. Activated antigen-specific CD8+ T cells persist in the lungs following recovery from respiratory virus infections. J. Immunol. 166:1813–1822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Huang L, Soldevila G, Leeker M, Flavell R, Crispe IN. 1994. The liver eliminates T cells undergoing antigen-triggered apoptosis in vivo. Immunity 1:741–749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Johnson LA, Jackson DG. 2008. Cell traffic and the lymphatic endothelium. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1131:119–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Klenk HD, Garten W. 1994. Host cell proteases controlling virus pathogenicity. Trends Microbiol. 2:39–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Klonowski KD, et al. 2004. Dynamics of blood-borne CD8 memory T cell migration in vivo. Immunity 20:551–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kohlmeier JE, et al. 2011. Inflammatory chemokine receptors regulate CD8(+) T cell contraction and memory generation following infection. J. Exp. Med. 208:1621–1634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kuiken T, Taubenberger JK. 2008. Pathology of human influenza revisited. Vaccine 26(Suppl 4):D59–D66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kunkel EJ, Butcher EC. 2002. Chemokines and the tissue-specific migration of lymphocytes. Immunity 16:1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kurachi M, et al. 2011. Chemokine receptor CXCR3 facilitates CD8(+) T cell differentiation into short-lived effector cells leading to memory degeneration. J. Exp. Med. 208:1605–1620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. La Gruta NL, Kedzierska K, Stambas J, Doherty PC. 2007. A question of self-preservation: immunopathology in influenza virus infection. Immunol. Cell Biol. 85:85–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lehmann C, et al. 2001. Lymphocytes in the bronchoalveolar space reenter the lung tissue by means of the alveolar epithelium, migrate to regional lymph nodes, and subsequently rejoin the systemic immune system. Anat. Rec. 264:229–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Luster AD, Alon R, von Andrian UH. 2005. Immune cell migration in inflammation: present and future therapeutic targets. Nat. Immunol. 6:1182–1190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. McMichael AJ, Gotch FM, Noble GR, Beare PA. 1983. Cytotoxic T-cell immunity to influenza. N. Engl. J. Med. 309:13–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Morgan DJ, et al. 1996. CD8(+) T cell-mediated spontaneous diabetes in neonatal mice. J. Immunol. 157:978–983 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Moskophidis D, Kioussis D. 1998. Contribution of virus-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T cells to virus clearance or pathologic manifestations of influenza virus infection in a T cell receptor transgenic mouse model. J. Exp. Med. 188:223–232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ottoson NC, Pribila JT, Chan AS, Shimizu Y. 2001. Cutting edge: T cell migration regulated by CXCR4 chemokine receptor signaling to ZAP-70 tyrosine kinase. J. Immunol. 167:1857–1861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ray SJ, et al. 2004. The collagen binding alpha1beta1 integrin VLA-1 regulates CD8 T cell-mediated immune protection against heterologous influenza infection. Immunity 20:167–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Reinhardt RL, Bullard DC, Weaver CT, Jenkins MK. 2003. Preferential accumulation of antigen-specific effector CD4 T cells at an antigen injection site involves CD62E-dependent migration but not local proliferation. J. Exp. Med. 197:751–762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Roman E, et al. 2002. CD4 effector T cell subsets in the response to influenza: heterogeneity, migration, and function. J. Exp. Med. 196:957–968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Schaeuble K, Hauser MA, Singer E, Groettrup M, Legler DF. 2011. Cross-talk between TCR and CCR7 signaling sets a temporal threshold for enhanced T lymphocyte migration. J. Immunol. 187:5645–5652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Stephens R, Randolph DA, Huang G, Holtzman MJ, Chaplin DD. 2002. Antigen-nonspecific recruitment of Th2 cells to the lung as a mechanism for viral infection-induced allergic asthma. J. Immunol. 169:5458–5467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tal O, et al. 2011. DC mobilization from the skin requires docking to immobilized CCL21 on lymphatic endothelium and intralymphatic crawling. J. Exp. Med. 208:2141–2153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Thelen M, Stein JV. 2008. How chemokines invite leukocytes to dance. Nat. Immunol. 9:953–959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ticchioni M, et al. 2002. Signaling through ZAP-70 is required for CXCL12-mediated T-cell transendothelial migration. Blood 99:3111–3118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Toapanta FR, Ross TM. 2009. Impaired immune responses in the lungs of aged mice following influenza infection. Respir. Res. 10:112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Topham DJ, Castrucci MR, Wingo FS, Belz GT, Doherty PC. 2001. The role of antigen in the localization of naive, acutely activated, and memory CD8(+) T cells to the lung during influenza pneumonia. J. Immunol. 167:6983–6990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Topham DJ, Tripp RA, Doherty PC. 1997. CD8+ T cells clear influenza virus by perforin or Fas-dependent processes. J. Immunol. 159:5197–5200 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Vigl B, et al. 2011. Tissue inflammation modulates gene expression of lymphatic endothelial cells and dendritic cell migration in a stimulus-dependent manner. Blood 118:205–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wareing MD, Lyon AB, Lu B, Gerard C, Sarawar SR. 2004. Chemokine expression during the development and resolution of a pulmonary leukocyte response to influenza A virus infection in mice. J. Leukoc. Biol. 76:886–895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wyde PR, Cate TR. 1978. Cellular changes in lungs of mice infected with influenza virus: characterization of the cytotoxic responses. Infect. Immun. 22:423–429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]