Abstract

The detachment of human immunodeficiency type 1 (HIV-1) virions depends on CHPM4 family members, which are late-acting components of the ESCRT pathway that mediate the cleavage of bud necks from the cytosolic side. We now show that in human cells, CHMP4 proteins are to a considerable extent bound to two high-molecular-weight proteins that we have identified as CC2D1A and CC2D1B. Both proteins bind to the core domain of CHMP4B, which has a strong propensity to polymerize and to inhibit HIV-1 budding. Further mapping showed that CC2D1A binds to an N-terminal hairpin within the CHMP4 core that has been implicated in polymerization. Consistent with a model in which CC2D1A and CC2D1B regulate CHMP4 polymerization, the overexpression of CC2D1A inhibited both the release of wild-type HIV-1 and the CHMP4-dependent rescue of an HIV-1 L domain mutant by exogenous ALIX. Furthermore, small interfering RNA against CC2D1A or CC2D1B increased HIV-1 budding under certain conditions. CC2D1A and CC2D1B possess four Drosophila melanogaster 14 (DM14) domains, and we demonstrate that these constitute novel CHMP4 binding modules. The DM14 domain that bound most avidly to CHMP4B was by itself sufficient to inhibit the function of ALIX in HIV-1 budding, indicating that the inhibition occurred through CHMP4 sequestration. However, N-terminal fragments of CC2D1A that did not interact with CHMP4B nevertheless retained a significant level of inhibitory activity. Thus, CC2D1A may also affect HIV-1 budding in a CHMP4-independent manner.

INTRODUCTION

Retroviruses hijack components of the host cell's endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) pathway via so-called late-assembly (L) domains in Gag to promote the detachment of nascent virions from the cell surface and from each other (3, 9, 14, 32, 54). The ESCRT pathway was discovered based on its requirement for the budding of cellular vesicles from the limiting membrane of multivesicular bodies (MVBs) into their lumen, which occurs away from the cytosol and thus resembles retroviral budding from the plasma membrane (21, 45). The components of the ESCRT pathway are highly conserved throughout eukaryotic evolution, and most of these components participate in the formation of five heterooligomeric complexes known as the ESCRT-0 to ESCRT-III and VPS4 complexes (22, 45). During MVB biogenesis, ESCRT-I and -II induce bud formation, and ESCRT-III, in concert with VPS4, carries out the scission of bud necks from the cytosolic side (55). ESCRT-III also carries out the scission of the membrane neck that forms between dividing cells during cytokinesis (4, 5, 38).

In contrast to the other ESCRT complexes, ESCRT-III is not a stable complex of a defined composition. Rather, ESCRT-III polymerizes on membranes in a highly regulated manner from monomeric cytosolic subunits (21). Humans encode at least 12 potential ESCRT-III subunits, most of which belong to seven charged MVB protein (CHMP) families (22). Six of these families also have a single member each in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and four of these are considered core ESCRT-III subunits based on their essential role in yeast MVB biogenesis (22). The CHMP proteins share an N-terminal core domain that folds into a four-helix bundle dominated by a hairpin formed by the first two helices (1, 40). Downstream of the core domain is an autoinhibitory region that is required to keep CHMP proteins in a closed soluble conformation (1, 29, 40, 47, 57).

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) recruits the ESCRT-III scission complex and VPS4 transiently to sites of virus assembly (2, 24). The recruitment of ESCRT-III occurs indirectly via a PTAP-type L domain in HIV-1 Gag that binds to Tsg101, a subunit of ESCRT-I (10, 17, 34, 52). However, how this ultimately triggers ESCRT-III assembly is not clear, because ESCRT-I couples to ESCRT-II, which is dispensable for HIV-1 budding (28). In addition to ESCRT-I, HIV-1 Gag engages an accessory component of the ESCRT pathway called ALIX, which binds directly to the ESCRT-III subunits CHMP4A to CHMP4C (11, 13, 15, 31, 33, 36, 43, 48, 53, 58). ALIX is less important for HIV-1 budding than ESCRT-I, but exogenous ALIX nonetheless potently rescues the budding defect of HIV-1 PTAP L domain mutants in a CHMP4-dependent manner (13, 51).

Most if not all CHMP proteins polymerize and become potent inhibitors of HIV-1 budding if their autoinhibition is released (47, 57). Nevertheless, only the CHMP2 and CHMP4 families are required for HIV-1 budding (39). When overexpressed, CHMP4 proteins have a propensity to form membrane-attached circular filaments that can promote outward budding (20). Interestingly, the single yeast homologue of human CHMP4A to CHMP4C (called Snf7) is the most crucial core ESCRT-III component for membrane scission (56). Snf7 is also the most abundant ESCRT-III component, and the other core ESCRT-III subunits are thought to regulate Snf7/CHMP4 polymerization (49). Certain ESCRT-III subunits assemble into dome-like structures in vitro, and dome-shaped CHMP4 polymers may thus drive HIV-1 budding (12, 30). Consistent with this model, ringlike structures potentially formed by CHMP4 were frequently detected within the necks of arrested HIV-1 buds on the surface of cells depleted of CHMP2 proteins (39).

In the present study, we observed that in human cells, CHMP4 family members are complexed with two high-molecular-weight proteins, and microsequencing revealed that these proteins are CC2D1A and CC2D1B. In contrast to other CHMP4 binding partners, CC2D1A and CC2D1B interact with a CHMP4B core domain fragment that blocks HIV-1 budding. Specifically, CC2D1A binds to an N-terminal helical hairpin that is thought to be involved in CHMP4 polymerization. When overexpressed, CC2D1A inhibited HIV-1 budding and abolished the ability of ALIX to rescue a Tsg101 binding-site mutant. Taken together, our results suggest a model in which CC2D1A regulates CHMP4 polymerization and determines the size of the pool that is available to function in HIV-1 budding.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Retroviral vectors and stable cell lines.

The coding sequences for full-length CHMP2, CHMP3, CHMP4A to CHMP4C, and CHMP6 with a C-terminal FLAG tag were inserted between the XhoI and EcoRI sites of the retroviral vector pMSCVpuro (Clontech). Additionally, the coding sequences for all CHMP proteins except CHMP7 were inserted between the XhoI and NotI sites of the pOZ-FH-N or pOZ-FH-C retroviral vector (42), in each case in frame with either N-terminal or C-terminal FLAG and hemagglutinin (HA) tags encoded by the vector. Stable cell lines were obtained by retroviral transduction followed by selection with puromycin or, in the case of the pOZ-based vectors, by multiple rounds of magnetic affinity sorting with an anti-interleukin-2 receptor alpha antibody as described previously (42).

Mammalian expression vectors.

The pBJ5-based expression vectors for CHMP4B-FLAG, FLAG-tagged CHMP4B1-153 (CHMP4B1-153FLAG), and HA-ALIX were described previously (48, 57). DNAs encoding CHMP4B residues 1 to 81, 1 to 92, 1 to 100, 1 to 108, 1 to 124, and 1 to 153 with an N-terminal FLAG tag were amplified from cDNA clone BC011429 (Open Biosystems, Huntsville, AL) and cloned into pBJ5. Additionally, DNAs encoding CHMP4B residues 19 to 224, 31 to 224, 33 to 224, 35 to 224, 37 to 224, 39 to 224, and 41 to 224 with a C-terminal FLAG tag were amplified from CHMP4B-FLAG and cloned into pBJ5. The coding sequence for full-length CC2D1A with an N-terminal HA tag was amplified from BC064981 (Open Biosystems) and cloned into pBJ5. The resulting construct was used as a template to amplify DNAs encoding CC2D1A residues 1 to 141, 1 to 181, 1 to 203, 1 to 350, 1 to 494, 1 to 554, 1 to 655, and 1 to 759 with an N-terminal HA tag, which were all cloned into pBJ5. A vector expressing full-length CC2D1A with a C-terminal HA tag was assembled from clone 023N (35) and BC006556 (Open Biosystems), and the coding sequence for full-length CC2D1B with an N-terminal HA tag was assembled from BQ073406 (Open Biosystems) and KIAA1836 (Kazusa DNA Research Institute) and cloned into pBJ5. For the mammalian expression of glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tagged proteins, PCR fragments encompassing CC2D1A residues 1 to 141, 1 to 181, 1 to 203, 135 to 198 (DM14 domain 1 [DM14/1]), 255 to 318 (DM14/2), 347 to 412 (DM14/3), and 492 to 556 (DM14/4) were inserted in frame between the EcoRI and XhoI sites of pCAGGS/GST (33).

Immunoaffinity purification and identification of CHMP protein interaction partners.

Cells stably expressing FLAG- or FLAG/HA-tagged CHMP proteins were lysed in 0.5% Nonidet P-40 (NP-40) in phosphate-buffered saline. Clarified lysates were incubated with anti-FLAG M2 antibody-conjugated agarose (Sigma-Aldrich), followed by extensive washing and elution of bound proteins with 300 μg/ml FLAG peptide, as described previously (42). Eluted proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and stained with colloidal Coomassie. Specific bands were excised and subjected to in-gel tryptic digestion, and extracted peptides were analyzed on a matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometer.

Coimmunoprecipitations.

Expression vectors for FLAG- and HA-tagged proteins were cotransfected into 293T cells by using a calcium-phosphate precipitation technique. At 24 h posttransfection, the cells were lysed in NP-40 buffer (0.5% NP-40, 20 mM Tris HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, and protease inhibitor cocktail [Complete; Roche Molecular Biochemicals]). The lysates were centrifuged at 16,000 × g and immunoprecipitated for 2.5 h at 4°C with anti-FLAG M2 antibody (Sigma-Aldrich). Immunoprecipitates and the cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-HA (HA.11; Covance) or anti-FLAG M2 antibody, as indicated.

GST pulldown assay.

293T cells were cotransfected with mammalian expression vectors for GST- and either HA- or FLAG-tagged proteins. Twenty-four hours later, the cells were lysed in 0.5% NP-40 buffer, and clarified lysates were incubated with glutathione-Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare) for 2.5 h at 4°C. After extensive washing in NP-40 buffer, bound proteins were eluted by boiling in SDS-PAGE sample buffer and resolved by SDS-PAGE. Epitope-tagged proteins were detected by Western blotting with anti-HA or anti-FLAG M2 antibody, and GST fusion proteins were visualized with colloidal Coomassie brilliant blue G-250.

Analysis of viral particle production.

293T cells were cotransfected with HIV-1 proviral DNA together with vectors expressing FLAG- or HA-tagged proteins and, in some cases, with small interfering RNA (siRNA), as indicated. The cells were transfected with calcium-phosphate-precipitated DNA or, in cases where siRNA was cotransfected, with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). The total amount of transfected DNA was kept constant with carrier DNA when calcium-phosphate precipitation was used. The HIV-1 proviral plasmids used were the infectious molecular clone HXBH10 and a variant (ΔPTAPP) with an in-frame deletion that removes the binding site for Tsg101 (27). Previously described stealth siRNA duplexes targeting CC2D1A (sense, CCCUGGCGAUCUGGAUGUCUUUGUU) (41) and CC2D1B (sense, CCCUGCAGCAGAGGCUGAACAAGUA) (19) and a matched stealth negative-control duplex (sense, CCCAGCGGUCUGUAGUUCUUGUGUU) were purchased from Invitrogen and used at 80 nM. At 24 h posttransfection, or 54 h posttransfection if siRNA was cotransfected, the cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (140 mM NaCl, 8 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM NaH2PO4, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.05% SDS). Culture supernatants were harvested from 6 to 24 h posttransfection, or from 48 to 54 h posttransfection if siRNA was used; clarified by low-speed centrifugation; and passaged through 0.45-μm filters. Virions released into the supernatants were then pelleted through 20% sucrose cushions by ultracentrifugation for 2 h at 27,000 rpm at 4°C in a Beckman SW41 rotor. Pelletable material and the cell lysates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with anti-HIV CA antibody 183-H12-5C (7). The cell lysates were also analyzed by Western blotting with anti-FLAG or anti-HA antibody and, where indicated, with a rabbit anti-CC2D1A polyclonal antibody (Bethyl Laboratories) and anti-actin antibody AC-40 (Sigma-Aldrich).

RESULTS

Human CHMP4 proteins interact with CC2D1A and CC2D1B in vivo.

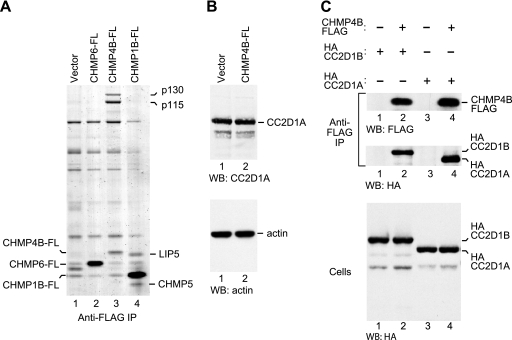

Among the ESCRT-III protein family members, CHMP4B is particularly important for HIV-1 virion release (39). To search for specific cellular binding partners, FLAG-tagged versions of CHMP4B and of other human CHMP proteins were stably expressed in 293T or HeLa S3 cells via retroviral transduction. The stable cell lines were lysed in 0.5% NP-40 buffer, and proteins precipitated from the lysates with anti-FLAG antibody were eluted with FLAG peptide, separated by SDS-PAGE, and visualized by Coomassie staining. As shown in Fig. 1A, two proteins of approximately 115 and 130 kDa (provisionally designated p115 and p130) specifically coprecipitated with CHMP4B but not with CHMP1B or CHMP6. The intensities of the p115 and p130 bands were comparable to that of the CHMP4B-FLAG band itself, suggesting that a considerable fraction of CHMP4B in human cells is bound to p115 and p130. The p115 and p130 bands also coprecipitated with CHMP4A and to a lesser extent with CHMP4C but not with CHMP1A, CHMP2A, CHMP2B, CHMP3, or CHMP5 (data not shown).

Fig 1.

CHMP4B interacts with CC2D1A and CC2D1B in vivo. (A) CHMP4B specifically interacts with two high-molecular-weight proteins in human cells. HeLa S3 cells stably expressing FLAG-tagged CHMP6, CHMP4B, or CHMP1B were lysed, and proteins precipitated with anti-FLAG antibody were eluted with FLAG peptide, separated by SDS-PAGE, and stained with colloidal Coomassie. Microsequencing revealed that p115 and p130 are CC2D1A and CC2D1B, respectively. Two proteins that coprecipitated with CHMP1B-FLAG were identified as LIP5 and CHMP5. (B) CHMP4B does not induce the expression of p115/CC2D1A. The lysates of HeLa S3 cells stably transduced with a retroviral vector expressing CHMP4B-FLAG or the empty vector were analyzed by Western blotting (WB) with antibodies against CC2D1A and actin. (C) Immunoprecipitations (IP) from 293T cells transiently expressing HA-tagged CC2D1A or CC2D1B together with full-length CHMP4B-FLAG.

Microsequencing of tryptic peptides derived from proteins coprecipitating with CHMP4B-FLAG unequivocally identified p115 as coiled-coil- and C2 domain-containing protein 1A (CC2D1A) (64% coverage) and p130 as the related protein CC2D1B (67% coverage). Consistent with these results, CC2D1A previously scored positive as a potential binding partner for human CHMP4 proteins in a yeast two-hybrid screen (50). Of note, Western blotting showed that the steady-state levels of endogenous CC2D1A in cells stably expressing CHMP4B-FLAG were not higher than those in control cells (Fig. 1B). We thus conclude that the remarkably high pulldown levels particularly of CC2D1A relative to the levels of CHMP4B-FLAG shown in Fig. 1A were not caused by an induction of CC2D1A expression by CHMP4B-FLAG.

CC2D1A and CC2D1B have calculated molecular masses of 104 and 94 kDa, respectively. It was therefore unexpected that CC2D1A (p115) exhibited a slower electrophoretic mobility than CC2D1B (p130). To confirm that p115 and p130 are CC2D1A and CC2D1B, we coexpressed CHMP4B-FLAG in transiently transfected 293T cells together with HA-tagged versions of CC2D1A or CC2D1B. The transfected cells were then lysed in 0.5% NP-40 buffer, and proteins precipitated from the lysates with anti-FLAG antibody were analyzed by Western blotting. As shown in Fig. 1C, HA-CC2D1A and HA-CC2D1B both coprecipitated with CHMP4B-FLAG. Importantly, when HA-CC2D1A and HA-CC2D1B were expressed alone, both were absent from anti-FLAG immunoprecipitates (Fig. 1C). As anticipated, HA-CC2D1B exhibited a slower electrophoretic mobility than HA-CC2D1A, confirming that CC2D1B migrates aberrantly in SDS-PAGE gels.

CC2D1A and CC2D1B interact with a CHMP4B core fragment that blocks HIV-1 budding.

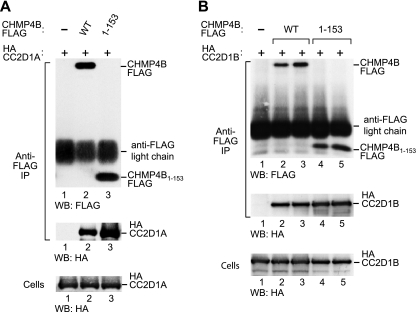

The previously identified CHMP4 interaction partners VPS4 and ALIX bind to elements near or at the C terminus of CHMP4 family members (26, 36). Apart from providing docking sites, the C terminus of CHMP4 has an autoinhibitory role (47, 57). Notably, the removal of C-terminal autoinhibitory sequences triggers CHMP protein polymerization along with a potent anti-HIV-1 budding activity (47, 57). For instance, we previously showed that HIV-1 release is profoundly inhibited by CHMP4B1–153FLAG, which lacks autoinhibitory helix 5 and the VPS4 and ALIX binding sites (57). CHMP4B1–153FLAG corresponds to the asymmetric four-helix bundle that has been termed the CHMP protein core (57). Therefore, we used CHMP4B1–153FLAG to determine whether the interaction with CC2D1A is mediated by the core or the C-terminal regulatory region of CHMP4B. As shown in Fig. 2A, HA-CC2D1A specifically coprecipitated with both full-length CHMP4B-FLAG and C-terminally truncated CHMP4B1–153FLAG. Indeed, in several independent experiments, the amount of HA-CC2D1A recovered with the truncation mutant exceeded that obtained with full-length CHMP4B (Fig. 2A and data not shown). Similarly, HA-CC2D1B coprecipitated at least as efficiently with CHMP4B1–153FLAG as with full-length CHMP4B (Fig. 2B). Thus, unlike VPS4 or ALIX, CC2D1A and CC2D1B bind to a CHMP4B core fragment that is capable of blocking HIV-1 budding.

Fig 2.

CC2D1A and CC2D1B interact with the core domain of CHMP4B. Shown are immunoprecipitations from 293T cells transiently expressing HA-CC2D1A (A) or HA-CC2D1B (B) and FLAG-tagged full-length CHMP4B or its core domain (CHMP4153). Proteins precipitated with anti-FLAG antibody and the cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting (WB), as indicated. The pulldown of HA-CC2D1B was examined in duplicate.

CC2D1A binds to an N-terminal helical hairpin of CHMP4B.

Members of the CHMP4 family are predicted to contain 6 helical segments, the first 5 of which are equivalent to helices in crystal structures of CHMP3 (1, 40). As illustrated in Fig. 3A, CHMP4B1–153 retains predicted helices 1 through 4, which, by analogy with CHMP3, form the core of CHMP4B (39). To examine the roles of individual helical segments of the core in the interaction with CC2D1A, we further truncated CHMP4B1–153 from the C terminus (Fig. 3A). The analysis of a panel of truncation mutants revealed that the first 100 CHMP4B residues were fully sufficient for the interaction with CC2D1A (Fig. 3B, lane 5). Within the CHMP protein core, these residues form a prominent N-terminal helical hairpin (40). Furthermore, CC2D1A coprecipitated equally well with CHMP4B1–92, indicating that the C terminus of the helical hairpin is not required for the interaction (Fig. 3B, lane 6). However, CC2D1A did not coprecipitate with CHMP4B1–81, which lacks almost half of the residues predicted to form helix 2 (Fig. 3B, lane 9).

Fig 3.

Ability of N-terminal CHMP4B fragments to bind CC2D1A and to inhibit HIV-1 budding. (A) Schematic illustration of the N-terminal CHMP4B fragments examined. Boxes indicate the predicted positions of α-helical regions in wild-type (WT) CHMP4B. (B) CC2D1A interacts with the N-terminal helical hairpin of the CHMP4B core. 293T cells were cotransfected with vectors expressing FLAG-tagged CHMP4B truncation mutants and HA-CC2D1A. The cell lysates and proteins immunoprecipitated with an anti-FLAG antibody were analyzed by Western blotting as indicated. (C) Effects on HIV-1 budding. 293T cells were cotransfected with wild-type HIV-1 proviral DNA and vectors expressing the indicated CHMP4B truncation mutants. Virion production and Gag protein expression levels were compared by Western blotting with an anti-CA antibody, and the expression of the CHMP4B truncation mutants was examined by Western blotting with an anti-FLAG antibody.

It was suggested previously that the N-terminal helical hairpin governs the ability of CHMP proteins to polymerize (1). Consistent with this notion, CHMP31–113, which essentially represents the CHMP3 helical hairpin, inhibits HIV-1 budding even when expressed at relatively low levels (57). However, it is not known whether the helical hairpin of CHMP4B shares this activity, and we therefore examined whether CHMP4B1–100 affects HIV-1 budding. Although CHMP4B1–100 did not share the effect of CHMP4B1–153 on HIV-1 budding, CHMP4B1–100 caused some accumulation of the Gag cleavage intermediates CA-p2 and p41 (Fig. 3C, lane 3), a hallmark of late-assembly defects (17, 18). However, CHMP4B1-92, the shortest C-terminal truncation mutant that still interacted with CC2D1A, inhibited neither HIV-1 release nor Gag processing (Fig. 3C, lane 4). Thus, the ability of CHMP4B hairpin fragments to interact with CC2D1A is not sufficient for the dominant negative inhibition of the ESCRT pathway.

To determine the role of the N-terminal end of the helical hairpin in the interaction with CC2D1A, we generated N-terminal truncation mutants of CHMP4B-FLAG (Fig. 4A) and used these mutants in coprecipitation experiments. CHMP4B31–end remained fully capable of interacting with CC2D1A (Fig. 4B, compare lanes 2 and 4), whereas CHMP4B41–end had lost this ability (lane 5). An analysis of additional truncation mutants revealed that the N-terminal 34 residues of CHMP4B are entirely dispensable for the interaction with CC2D1A (Fig. 4B, lane 8), whereas the deletion of an additional 2 residues in CHMP4B37–end nearly abolished the interaction (Fig. 4B, lane 9). We also examined the effects of the N-terminal truncations on the ability of the CHMP4B core fragment CHMP4B1-153FLAG to inhibit HIV-1 budding. CHMP4B19-153FLAG, which retained the entire helical hairpin, remained capable of inhibiting HIV-1 Gag processing and budding (Fig. 4C, lane 3) albeit to a lesser extent than CHMP4B1-153FLAG (lane 2). However, all truncations which extended into the region forming helix 1 abolished the inhibition of HIV-1 Gag processing and budding by the CHMP4B core (Fig. 4C, lane 4, and data not shown). Together, these data imply that CC2D1A binds to a central portion of a helical hairpin, whose integrity is critical for the dominant negative inhibition of HIV-1 budding by the CHMP4B core.

Fig 4.

Role of the CHMP4B N terminus. (A) Schematic illustration of N-terminal CHMP4B truncation mutants. (B) Effects of the truncations on the interaction between CHMP4B and CC2D1A, analyzed as described in the legend of Fig. 3B. (C) Effects of selected N-terminal truncations on the ability of the CHMP4B core domain to inhibit HIV-1 budding and Gag processing, analyzed as described in the legend of Fig. 3C.

CC2D1A inhibits HIV-1 budding.

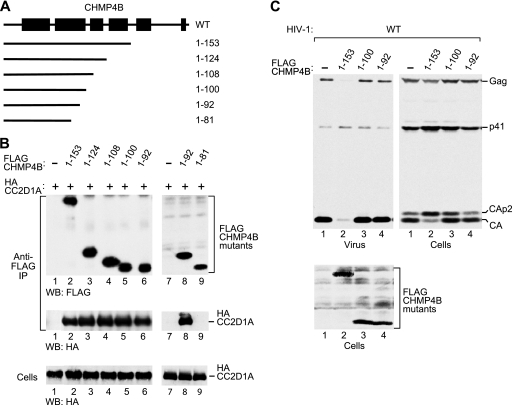

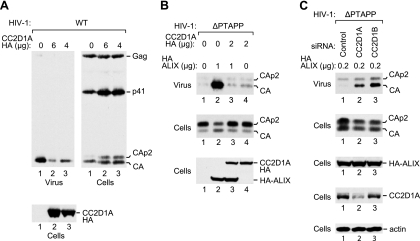

A recent study demonstrated that CHMP4 proteins are transiently recruited late during HIV-1 assembly, presumably to carry out the membrane fission required for virion release (24). Consistent with this notion, the codepletion of CHMP4 family members profoundly inhibits the release of HIV-1 virions (39). Since our data indicated that CHMP4A and CHMP4B bind avidly to CC2D1 proteins, we considered the possibility that the expression levels of CC2D1A or CC2D1B affect the availability of CHMP4 family members during HIV-1 budding. To test this possibility, we cotransfected 293T cells with HXBH10, a replication-competent HIV-1 provirus, and different amounts of a vector expressing CC2D1A-HA. As shown in Fig. 5A, CC2D1A inhibited the release of wild-type HIV-1 virions in a dose-dependent manner, as monitored by the release of particle-associated CA into the medium. Furthermore, the overexpression of CC2D1A led to the accumulation of the Gag cleavage intermediates CA-p2 and p41 in the transfected cells, as expected if a late assembly step is defective (Fig. 5A).

Fig 5.

CC2D1A inhibits HIV-1 budding. (A) Effect of CC2D1A overexpression on wild-type HIV-1. 293T cells were cotransfected with wild-type HIV-1 proviral DNA (1 μg) and the indicated amounts of a vector expressing CC2D1A-HA. (B) Effect of CC2D1A overexpression on the rescue of HIV-1ΔPTAPP by ALIX. 293T cells were cotransfected with ΔPTAPP HIV-1 proviral DNA (1 μg), together with pBJ5-based vectors expressing HA-ALIX (1 μg) or CC2D1A-HA (2 μg) or with empty pBJ5, as indicated. Virion pellets and the cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-CA and anti-HA antibodies to detect Gag, Gag cleavage products, and HA-tagged proteins. (C) Effects of siRNAs against CC2D1A or CC2D1B on the release of ΔPTAPP HIV-1 in the presence of a suboptimal amount of HA-ALIX. 293T cells were cotransfected with ΔPTAPP HIV-1 proviral DNA (0.5 μg), together with the vector expressing HA-ALIX (0.2 μg) and the indicated siRNAs (80 nM). Pelleted virions harvested at 48 to 54 h posttransfection and the cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-CA, anti-HA, anti-CC2D1A, or anti-actin antibodies, as indicated.

We also examined whether exogenous CC2D1A affects the function of ALIX in virus budding. We and others previously showed that exogenous ALIX efficiently rescues the profound release defect of HIV-1 mutants that lack the PTAP-type primary L domain (13, 51). ALIX selectively interacts with CHMP4 family members, particularly with CHMP4B (13, 25), and point mutations in the Bro1 domain of ALIX that eliminate the interaction with CHMP4B abolish the rescue of ΔPTAPP HIV-1 by ALIX (13, 51). Because these results indicated that ALIX must interact with CHMP4 proteins to function in HIV-1 budding, we determined the effect of exogenous CC2D1A in the ΔPTAPP rescue assay. Even at relatively low expression levels, CC2D1A-HA blocked the ability of HA-ALIX to rescue ΔPTAPP HIV-1 in terms of both particle production and Gag processing (Fig. 5B, lane 3). Importantly, CC2D1A-HA had no effect on the expression levels of HA-ALIX. Also, CC2D1A-HA did not reduce the low level of particle production by ΔPTAPP HIV-1 obtained in the absence of ALIX-HA, implying that CC2D1A specifically affected the function of ALIX (Fig. 5B, lane 4).

We next asked whether the depletion of CC2D1A or CC2D1B increases particle production under conditions where HIV-1 budding is attenuated. To this end, we cotransfected 293T cells with the ΔPTAPP mutant along with a small amount of the HA-ALIX expression vector. When cotransfected with a control siRNA, this amount was insufficient to trigger the release of mature CA (Fig. 5C, lane 1). However, the cotransfection of siRNAs against CC2D1A or CC2D1B stimulated the release of CA and reduced the levels of cell-associated CA-p2 without affecting the expression levels of HA-ALIX (Fig. 5C, lanes 2 and 3). As expected, only the siRNA against CC2D1A depleted the transfected cells of CC2D1A protein (Fig. 5C). The effectiveness of the siRNA against CC2D1B was previously demonstrated (19). Taken together, these results support the notion that CC2D1 proteins inhibit the ability of CHMP4 family members to participate in HIV-1 budding events.

Role of DM14 domains in CHMP4 binding and in the inhibition of HIV-1 budding.

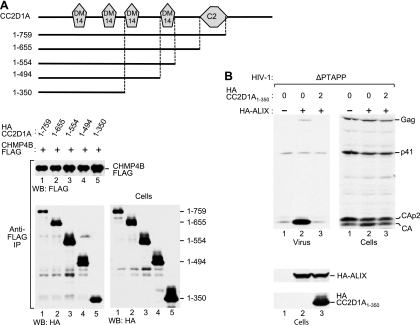

CC2D1A and CC2D1B harbor four Drosophila melanogaster 14 (DM14) domains that are unique to these proteins and have no known function and a protein kinase C conserved region 2 (C2) domain that follows upon the DM14 domains (Fig. 6A). To determine the contribution of these domains and of intervening sequences to the interaction with CHMP4B, we generated a series of C-terminal truncation mutants of CC2D1A. Taking into account their cellular expression levels, the CC2D1A truncation mutants encompassing residues 1 to 759, 1 to 655, 1 to 554, and 1 to 494 appeared to coprecipitate equally well with CHMP4B-FLAG, indicating that the region N terminal to the fourth DM14 domain was fully sufficient for the interaction in vivo (Fig. 6A, lanes 1 to 4). However, the mutant encompassing residues 1 to 350, which retains only 2 DM14 domains, coprecipitated less efficiently (about 3- to 4-fold) relative to its expression level (Fig. 6A, lane 5). Nevertheless, HA-CC2D1A1-350 remained fully capable of blocking the effect of ALIX on HIV-1 budding in the ΔPTAPP rescue assay (Fig. 6B). As expected from this result, the function of ALIX in HIV-1 budding was also blocked by the mutants encompassing residues 1 to 759, 1 to 655, 1 to 554, and 1 to 494 (data not shown). Together, these findings suggested a role for DM14 domains in the interaction with CHMP4B and in the inhibition of ALIX function.

Fig 6.

Ability of CC2D1A truncation mutants to bind CHMP4B and to inhibit the function of ALIX in HIV-1 budding. (A) Ability of CC2D1A truncation mutants to interact with CHMP4B. The schematically illustrated HA-tagged CC2D1A mutants were expressed in 293T cells together with CHMP4B-FLAG. The cell lysates and proteins immunoprecipitated with an anti-FLAG antibody were analyzed by Western blotting, as indicated. (B) Effect of CC2D1A1–350 on the rescue of HIV-1ΔPTAPP by ALIX. 293T cells were cotransfected with ΔPTAPP HIV-1 proviral DNA (1 μg), together with pBJ5-based vectors expressing HA-ALIX (2 μg) or HA-CC2D1A1–350 (2 μg) or with empty pBJ5, as indicated. Virion pellets and the cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-CA and anti-HA antibodies to detect Gag, Gag cleavage products, ALIX, and CC2D1A1–350.

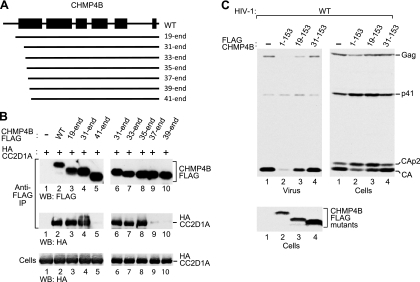

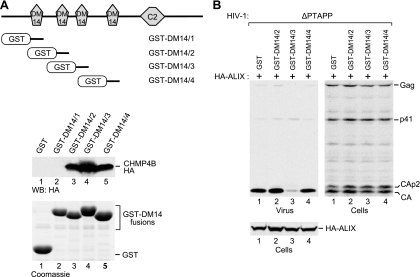

To determine directly whether DM14 domains bind CHMP4B, each of the four DM14 domains of CC2D1A was individually fused to the C terminus of GST in the context of a mammalian expression vector. We then expressed the GST-DM14 fusion proteins in 293T cells together with HA-tagged CHMP4B and performed GST pulldown assays. Although the first DM14 domain of CC2D1A did not pull down any CHMP4B-HA when fused to GST, the isolated second, third, and fourth DM14 domains clearly interacted with CHMP4B in the same context (Fig. 7A). We also tested the effects of the CHMP4B-binding fusion proteins in the ΔPTAPP rescue assay and found that only the construct harboring the third DM14 domain of CC2D1A inhibited the rescue of ΔPTAPP HIV-1 by ALIX (Fig. 7B). As shown in Fig. 7A, the third DM14 domain also pulled down more CHMP4B than did DM14 domains 2 and 4. Thus, 3 of the 4 DM14 domains of CC2D1A constitute autonomous CHMP4B binding modules, and the DM14 domain that interacts most avidly with CHMP4B is by itself capable of inhibiting the function of ALIX in HIV-1 budding.

Fig 7.

CHMP4B binding by isolated DM14 domains and their effects on the function of ALIX in HIV-1 budding. (A) Ability of GST-DM14 domain fusion proteins to pull down CHMP4B. The schematically illustrated GST fusion proteins were expressed in 293T cells together with CHMP4B-HA, and proteins precipitated from the cell lysates by glutathione-Sepharose beads were analyzed by Western blotting with an anti-HA antibody or by Coomassie staining to detect the GST-DM14 fusion proteins. (B) Effects of the GST-DM14 domain fusion proteins on the rescue of HIV-1ΔPTAPP by ALIX. 293T cells were cotransfected with ΔPTAPP HIV-1 proviral DNA, a vector expressing HA-ALIX, and vectors expressing GST or the indicated GST-DM14 domain fusion proteins. Virion pellets and the cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-CA and anti-HA antibodies to detect Gag, Gag cleavage products, and ALIX.

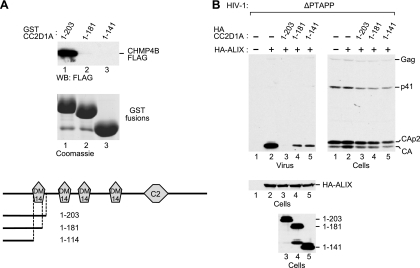

Since the first DM14 domain (CC2D1A residues 135 to 198) was unique in its inability to interact with CHMP4B, we examined whether DM14 domain 1 mediates CHMP4B binding in the presence of additional residues that flank the domain in the context of intact CC2D1A. Indeed, a GST fusion protein that harbored an N-terminal CC2D1A fragment that extended slightly beyond the first DM14 domain (GST-CC2D1A1-203) interacted robustly with CHMP4B (Fig. 8A, lane 1). To determine whether an intact DM14 domain was required for CHMP4B binding in this context, the DM14 domain was either truncated or deleted, yielding GST-CC2D1A1-181 and GST-CC2D1A1-141, respectively. Both modifications abolished binding to CHMP4B (Fig. 8A, lanes 2 and 3), demonstrating that the interaction depended on the integrity of the DM14 domain. In the ΔPTAPP rescue assay, CHMP4 binding-competent CC2D1A1-203 completely abolished the ability of ALIX to promote HIV-1 budding (Fig. 8B, lane 3). However, despite their inability to interact with CHMP4B, CC2D1A1-181 and CC2D1A1-141 also inhibited the effect of ALIX on HIV-1 budding albeit to a lesser extent than did CC2D1A1-203 (Fig. 8B, lanes 4 and 5). Taken together, these results indicate that the inhibition of HIV-1 budding by CC2D1A occurs both via the sequestration of CHMP4 proteins by DM14 domains and via a CHMP4-independent mechanism.

Fig 8.

DM14 domain 1-dependent CHMP4B binding and inhibition of HIV-1 budding by an N-terminal CC2D1A fragment. (A) DM14 domain 1 is required for CHMP4B binding by an N-terminal CC2D1A fragment. The schematically illustrated GST fusion proteins were expressed in 293T cells together with CHMP4B-FLAG, and proteins precipitated from the cell lysates by glutathione-Sepharose beads were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-FLAG antibody or by Coomassie staining to detect the GST-DM14 fusion proteins. (B) Effects of the N-terminal CC2D1A fragments on the rescue of HIV-1ΔPTAPP by ALIX.

DISCUSSION

Although most CHMP proteins can be converted into strong dominant negative inhibitors of HIV-1 particle production, siRNA depletion experiments have revealed that only the CHMP2 and CHMP4 families are in fact required for HIV-1 budding (39). While the members of these two families exhibit redundancy, CHMP4B appears particularly important, because its individual depletion had the greatest effect on HIV-1 release (39).

In the present study, we provide evidence that a large fraction of cellular CHMP4B exists in a complex with high-molecular-weight proteins that we have identified as CC2D1A and CC2D1B. Both proteins additionally interacted with CHMP4A and CHMP4C in human cells but not with any other ESCRT-III component. CC2D1A is identical to Freud-1, which has been implicated in transcriptional regulation and in nonsyndromic mental retardation (44, 59). Consistent with our findings, CC2D1A was among a large collection of potential CHMP protein auxiliary factors that emerged from a yeast two-hybrid screen, in which CC2D1A also interacted only with CHMP4 proteins (50). A connection to the ESCRT pathway is further implied by the phenotype caused by mutations in the Drosophila protein Lethal giant discs (Lgd), the homologue of human CC2D1A and CC2D1B. Specifically, the absence of Lgd leads to the accumulation and ectopic activation of Notch in an endosomal compartment, which is also observed if the function of ESCRT components is lost, for instance, that of the Drosophila CHMP4 homologue (8, 16, 23). Human CC2D1A is also known as Aki1, which has been shown to localize to centrosomes (41). Interestingly, the depletion of CC2D1A/Aki1 results in the formation of multipolar spindles during mitosis (41), and cells depleted of CHMP4B or CHMP4C also exhibit multipolar spindles (37).

Our results suggest that CC2D1A and CC2D1B control the polymerization of CHMP4 filaments, which are thought to drive the scission of bud necks from the cytosolic side, for instance, during HIV-1 budding. When overexpressed, human CHMP4A and CHMP4B assemble into membrane-attached circular filaments that can induce the outward budding of tubules at the plasma membrane (20). Functional reconstitution studies with purified yeast ESCRT-III proteins support the notions that CHMP4 family members self-assemble into oligomers that induce membrane deformation and that the other ESCRT-III core components function in the nucleation or termination of CHMP4 oligomerization (46). To control ESCRT-III formation, ESCRT-III components are by default kept in a closed conformation through an autoinhibitory mechanism (29, 40, 47, 57). However, the propensity of CHMP4 family members to polymerize may require an additional level of regulation through proteins such as CC2D1A/B that bind to the region through which activated CHMP4 self-associates. Consistent with this model, we find that CC2D1A and CC2D1B strongly interact with a CHMP4B core fragment that is constitutively activated, based on its ability to prevent HIV-1 budding (57). Moreover, additional mapping revealed that CC2D1A binds to the helical hairpin that dominates the CHMP core domain and has been implicated in filament formation (1, 40). Further support for a model in which CC2D1A regulates CHMP4 polymerization is provided by our finding that exogenous CC2D1A inhibited the release of wild-type HIV-1 and the rescue of ΔPTAPP HIV-1 by ALIX, both of which depend on CHMP4 (13, 39, 51).

CC2D1A and CC2D1B are the only human members of a protein family harboring four DM14 domains and a C-terminal C2 domain. It was shown previously that the C2 domain of the CC2D1A homologue Lgd binds phospholipids and is required for the membrane association of Lgd in vivo (16). However, the function of the DM14 domains has remained unknown. We now show that DM14 domains constitute CHMP4 binding modules that can function autonomously, as demonstrated by our observation that the second, third, and fourth DM14 domains of CC2D1A bound CHMP4B even in isolation. However, only the isolated third DM14 domain, which bound most avidly, was sufficient to block the function of ALIX in HIV-1 budding. Together, these results suggest that only the third DM14 domain retained a sufficiently high affinity to block CHMP4 polymerization by itself. It appears less likely that competition with the Bro1 domain of ALIX for CHMP4 binding played a role, because our results imply that DM14 domains bind to the CHMP4 core. In contrast, ALIX binds to the C terminus of CHMP4 family members (36). The first DM14 domain did not bind CHMP4B but mediated CHMP4 binding in the context of a larger N-terminal fragment. Surprisingly, the disruption or removal of the DM14 domain, which prevented CHMP4 binding, only mitigated but did not abolish the ability of the N-terminal fragment to inhibit the function of ALIX in HIV-1 budding. It thus appears that CC2D1A inhibits the activity of ALIX not only via the sequestration of CHMP4 proteins. Consistent with this notion, we were unable to alleviate the inhibitory effect of CC2D1A overexpression on the function of ALIX through the simultaneous overexpression of CHMP4B (data not shown).

In a recent study, CC2D1A was found to localize to endolysosomal compartments in human cells (6), which would be consistent with a role in regulating the polymerization of CHMP4 proteins on endosomal membranes. That same study and earlier work also indicated that CC2D1A activates signaling pathways involved in innate immunity, including the NF-κB pathway (6, 35, 59). Notably, the overexpression of CC2D1A induced endogenous beta interferon and led to an antiviral state (6). Our observation that CC2D1A binds to CHMP4 proteins via its DM14 domains thus raises the possibility that components of the ESCRT pathway play specific roles in innate antiviral defense mechanisms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Paul Bieniasz for pCAGGS/GST, Yoshihiro Nakatani for pOZ-FH-N and pOZ-FH-C, Akio Matsuda for clone 023N, Tahakiro Nagase and the Kazusa DNA Research Institute for KIAA1836, and Steven Gygi and John Leszyk for protein microsequencing. The following reagent was obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: HIV-1 p24 monoclonal antibody (183-H12-5C), from Bruce Chesebro and Kathy Wehrly.

This work was supported by grant R37AI029873 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 18 January 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Bajorek M, et al. 2009. Structural basis for ESCRT-III protein autoinhibition. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16:754–762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baumgartel V, et al. 2011. Live-cell visualization of dynamics of HIV budding site interactions with an ESCRT component. Nat. Cell Biol. 13:469–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bieniasz PD. 2009. The cell biology of HIV-1 virion genesis. Cell Host Microbe 5:550–558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Caballe A, Martin-Serrano J. 2011. ESCRT machinery and cytokinesis: the road to daughter cell separation. Traffic 12:1318–1326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Carlton JG, Martin-Serrano J. 2007. Parallels between cytokinesis and retroviral budding: a role for the ESCRT machinery. Science 316:1908–1912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chang CH, et al. 2011. TBK1-associated protein in endolysosomes (TAPE) is an innate immune regulator modulating the TLR3 and TLR4 signaling pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 286:7043–7051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chesebro B, Wehrly K, Nishio J, Perryman S. 1992. Macrophage-tropic human immunodeficiency virus isolates from different patients exhibit unusual V3 envelope sequence homogeneity in comparison with T-cell-tropic isolates: definition of critical amino acids involved in cell tropism. J. Virol. 66:6547–6554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Childress JL, Acar M, Tao C, Halder G. 2006. Lethal giant discs, a novel C2-domain protein, restricts notch activation during endocytosis. Curr. Biol. 16:2228–2233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Demirov DG, Freed EO. 2004. Retrovirus budding. Virus Res. 106:87–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Demirov DG, Ono A, Orenstein JM, Freed EO. 2002. Overexpression of the N-terminal domain of TSG101 inhibits HIV-1 budding by blocking late domain function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:955–960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dussupt V, et al. 2009. The nucleocapsid region of HIV-1 Gag cooperates with the PTAP and LYPXnL late domains to recruit the cellular machinery necessary for viral budding. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fabrikant G, et al. 2009. Computational model of membrane fission catalyzed by ESCRT-III. PLoS Comput. Biol. 5:e1000575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fisher RD, et al. 2007. Structural and biochemical studies of ALIX/AIP1 and its role in retrovirus budding. Cell 128:841–852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fujii K, Hurley JH, Freed EO. 2007. Beyond Tsg101: the role of Alix in ‘ESCRTing’ HIV-1. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5:912–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fujii K, et al. 2009. Functional role of Alix in HIV-1 replication. Virology 391:284–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gallagher CM, Knoblich JA. 2006. The conserved c2 domain protein lethal (2) giant discs regulates protein trafficking in Drosophila. Dev. Cell 11:641–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Garrus JE, et al. 2001. Tsg101 and the vacuolar protein sorting pathway are essential for HIV-1 budding. Cell 107:55–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gottlinger HG, Dorfman T, Sodroski JG, Haseltine WA. 1991. Effect of mutations affecting the p6 gag protein on human immunodeficiency virus particle release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 88:3195–3199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hadjighassem MR, Galaraga K, Albert PR. 2011. Freud-2/CC2D1B mediates dual repression of the serotonin-1A receptor gene. Eur. J. Neurosci. 33:214–223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hanson PI, Roth R, Lin Y, Heuser JE. 2008. Plasma membrane deformation by circular arrays of ESCRT-III protein filaments. J. Cell Biol. 180:389–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Henne WM, Buchkovich NJ, Emr SD. 2011. The ESCRT pathway. Dev. Cell 21:77–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hurley JH. 2010. The ESCRT complexes. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 45:463–487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jaekel R, Klein T. 2006. The Drosophila Notch inhibitor and tumor suppressor gene lethal (2) giant discs encodes a conserved regulator of endosomal trafficking. Dev. Cell 11:655–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jouvenet N, Zhadina M, Bieniasz PD, Simon SM. 2011. Dynamics of ESCRT protein recruitment during retroviral assembly. Nat. Cell Biol. 13:394–401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Katoh K, Shibata H, Hatta K, Maki M. 2004. CHMP4b is a major binding partner of the ALG-2-interacting protein Alix among the three CHMP4 isoforms. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 421:159–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kieffer C, et al. 2008. Two distinct modes of ESCRT-III recognition are required for VPS4 functions in lysosomal protein targeting and HIV-1 budding. Dev. Cell 15:62–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 27. Kondo E, Gottlinger HG. 1996. A conserved LXXLF sequence is the major determinant in p6gag required for the incorporation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr. J. Virol. 70:159–164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Langelier C, et al. 2006. Human ESCRT-II complex and its role in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 release. J. Virol. 80:9465–9480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lata S, et al. 2008. Structural basis for autoinhibition of ESCRT-III CHMP3. J. Mol. Biol. 378:816–825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lata S, et al. 2008. Helical structures of ESCRT-III are disassembled by VPS4. Science 321:1354–1357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lee S, Joshi A, Nagashima K, Freed EO, Hurley JH. 2007. Structural basis for viral late-domain binding to Alix. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14:194–199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Martin-Serrano J, Neil SJ. 2011. Host factors involved in retroviral budding and release. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9:519–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Martin-Serrano J, Yarovoy A, Perez-Caballero D, Bieniasz PD. 2003. Divergent retroviral late-budding domains recruit vacuolar protein sorting factors by using alternative adaptor proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:12414–12419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Martin-Serrano J, Zang T, Bieniasz PD. 2001. HIV-1 and Ebola virus encode small peptide motifs that recruit Tsg101 to sites of particle assembly to facilitate egress. Nat. Med. 7:1313–1319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Matsuda A, et al. 2003. Large-scale identification and characterization of human genes that activate NF-kappaB and MAPK signaling pathways. Oncogene 22:3307–3318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McCullough J, Fisher RD, Whitby FG, Sundquist WI, Hill CP. 2008. ALIX-CHMP4 interactions in the human ESCRT pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:7687–7691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Morita E, et al. 2010. Human ESCRT-III and VPS4 proteins are required for centrosome and spindle maintenance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:12889–12894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Morita E, et al. 2007. Human ESCRT and ALIX proteins interact with proteins of the midbody and function in cytokinesis. EMBO J. 26:4215–4227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Morita E, et al. 2011. ESCRT-III protein requirements for HIV-1 budding. Cell Host Microbe 9:235–242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Muziol T, et al. 2006. Structural basis for budding by the ESCRT-III factor CHMP3. Dev. Cell 10:821–830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nakamura A, Arai H, Fujita N. 2009. Centrosomal Aki1 and cohesin function in separase-regulated centriole disengagement. J. Cell Biol. 187:607–614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nakatani Y, Ogryzko V. 2003. Immunoaffinity purification of mammalian protein complexes. Methods Enzymol. 370:430–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Popov S, Popova E, Inoue M, Gottlinger HG. 2008. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag engages the Bro1 domain of ALIX/AIP1 through the nucleocapsid. J. Virol. 82:1389–1398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rogaeva A, Galaraga K, Albert PR. 2007. The Freud-1/CC2D1A family: transcriptional regulators implicated in mental retardation. J. Neurosci. Res. 85:2833–2838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Saksena S, Sun J, Chu T, Emr SD. 2007. ESCRTing proteins in the endocytic pathway. Trends Biochem. Sci. 32:561–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Saksena S, Wahlman J, Teis D, Johnson AE, Emr SD. 2009. Functional reconstitution of ESCRT-III assembly and disassembly. Cell 136:97–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Shim S, Kimpler LA, Hanson PI. 2007. Structure/function analysis of four core ESCRT-III proteins reveals common regulatory role for extreme C-terminal domain. Traffic 8:1068–1079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Strack B, Calistri A, Craig S, Popova E, Gottlinger HG. 2003. AIP1/ALIX is a binding partner for HIV-1 p6 and EIAV p9 functioning in virus budding. Cell 114:689–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Teis D, Saksena S, Emr SD. 2008. Ordered assembly of the ESCRT-III complex on endosomes is required to sequester cargo during MVB formation. Dev. Cell 15:578–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tsang HT, et al. 2006. A systematic analysis of human CHMP protein interactions: additional MIT domain-containing proteins bind to multiple components of the human ESCRT III complex. Genomics 88:333–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Usami Y, Popov S, Gottlinger HG. 2007. Potent rescue of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 late domain mutants by ALIX/AIP1 depends on its CHMP4 binding site. J. Virol. 81:6614–6622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. VerPlank L, et al. 2001. Tsg101, a homologue of ubiquitin-conjugating (E2) enzymes, binds the L domain in HIV type 1 Pr55(Gag). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:7724–7729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. von Schwedler UK, et al. 2003. The protein network of HIV budding. Cell 114:701–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Weiss ER, Gottlinger H. 2011. The role of cellular factors in promoting HIV budding. J. Mol. Biol. 410:525–533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wollert T, Hurley JH. 2010. Molecular mechanism of multivesicular body biogenesis by ESCRT complexes. Nature 464:864–869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wollert T, Wunder C, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Hurley JH. 2009. Membrane scission by the ESCRT-III complex. Nature 458:172–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zamborlini A, et al. 2006. Release of autoinhibition converts ESCRT-III components into potent inhibitors of HIV-1 budding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:19140–19145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zhai Q, et al. 2008. Structural and functional studies of ALIX interactions with YPX(n)L late domains of HIV-1 and EIAV. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15:43–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zhao M, Li XD, Chen Z. 2010. CC2D1A, a DM14 and C2 domain protein, activates NF-kappaB through the canonical pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 285:24372–24380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]