Abstract

Objective

To conduct a cross-national comparative study of the prevalence and correlates of female genital cutting (FGC) practices and beliefs in western Africa.

Methods

Data from women who responded to the Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys between 2005 and 2007 were used to estimate the frequencies of ever having been circumcised, having had a daughter circumcised, and believing that FGC practices should continue. Weighted logistic regression using data for each country was performed to determine the independent correlates of each outcome.

Findings

The prevalence of FGC was high overall but varied substantially across countries in western Africa. In Sierra Leone, Gambia, Burkina Faso and Mauritania, the prevalence of FGC was 94%, 79%, 74% and 72%, respectively, whereas in Ghana, Niger and Togo prevalence was less than 6%. Older age and being Muslim were generally associated with increased odds of FGC, and higher education was associated with lower odds of FGC. The association between FGC and wealth varied considerably. Burkina Faso was the only country in our study that experienced a dramatic reduction in FGC prevalence from women (74%) to their daughters (25%); only 14.2% of the women surveyed in that country said that they believe the practice should continue.

Conclusion

The prevalence of FGC in western Africa remains high overall but varies substantially across countries. Given the broad range of experiences, successful strategies from countries where FGC is declining may provide useful examples for high-prevalence countries seeking to reduce their own FGC practices.

Résumé

Objectif

Réaliser une étude comparative transnationale de la prévalence et des indicateurs des pratiques et croyances en matière de mutilations génitales féminines (MGF) en Afrique de l’Ouest.

Méthodes

Les données fournies par des femmes ayant répondu aux enquêtes en grappes à indicateurs multiples entre 2005 et 2007 ont servi à estimer la fréquence avec laquelle elles avaient été excisées, avaient fait exciser une ou plusieurs de leurs filles et pensaient que les pratiques de MGF devaient se poursuivre. Une régression logistique pondérée a été réalisée afin de déterminer les indicateurs autonomes de chaque résultat.

Résultats

La prévalence des MGF était généralement élevée mais variait de manière significative d’un pays d’Afrique de l’Ouest à l’autre. En Sierra Leone, Gambie, Burkina Faso et Mauritanie, la prévalence des MGF était de 94%, 79%, 74% et 72%, respectivement, alors qu’au Ghana, Niger et Togo, cette prévalence était inférieure à 6%. Un âge plus avancé et le fait d’être musulmane constituaient des facteurs généralement associés à des risques accrus de MGF et un degré d’éducation plus élevé était associé à des risques plus faibles. L’association entre MGF et aisance financière variait considérablement. Le Burkina Faso était le seul pays de notre étude à avoir noté une diminution spectaculaire des MGF des femmes (74%) à leurs filles (25%); seules 14,2% des femmes interrogées dans ce pays ont déclaré penser que cette pratique devait se poursuivre.

Conclusion

La prévalence des MGF en Afrique de l’Ouest reste généralement élevée mais varie de manière significative d’un pays à l’autre. Compte tenu du large éventail d’expériences, des stratégies réussies dans des pays où les MGF sont en baisse peuvent fournir des exemples utiles à des pays à forte prévalence désireux de diminuer leurs propres pratiques de MGF.

Resumen

Objetivo

Llevar a cabo un estudio comparativo entre países de África occidental sobre la prevalencia y correlación de las prácticas de mutilación genital femenina (MGF) y las creencias relacionadas.

Métodos

Se emplearon los datos procedentes de las mujeres que respondieron a las Encuestas de Indicadores Múltiples por Conglomerados entre 2005 y 2007 para calcular el porcentaje de mujeres que habían sido sometidas a una ablación, el de hijas de dichas mujeres que habían sido sometidas a una ablación y la creencia de que las prácticas de MGF deberían mantenerse. Se realizó una regresión logística ponderada empleando los datos procedentes de cada país para determinar las correlaciones independientes de cada resultado.

Resultados

La prevalencia de la MGF fue alta en general, si bien variaba de manera sustancial en los diversos países de África occidental. En Sierra Leona, Gambia, Burkina Faso y Mauritania, la prevalencia de la MGF fue de un 94%, 79%, 74% y 72%, respectivamente, mientras que en Ghana, Níger y Togo la prevalencia fue inferior al 6%. Una edad más avanzada y la condición de musulmana se asociaron generalmente a una mayor probabilidad de haber sufrido una MGF, mientras que se asoció una educación superior a una menor probabilidad de MGF. La asociación entre MGF y riqueza variaba ostensiblemente. Burkina Faso fue el único país dentro del estudio que experimentó una reducción drástica en la prevalencia de la MGF entre las madres (74%) y las hijas (25%). Solo el 14,2% de las mujeres encuestadas en dicho país afirmaron considerar que debía continuarse con dicha práctica.

Conclusión

La prevalencia de la MGF en África occidental sigue siendo elevada en general, si bien varía sustancialmente entre los diversos países. Teniendo en consideración la amplia variedad de experiencias, las estrategias fructíferas en países donde la MGF está descendiendo podrían servir de ejemplo útil a los países con una mayor prevalencia que deseen reducir sus prácticas de MGF.

ملخص

الغرض

إجراء دراسة مقارنة شاملة لعدة بلدان حول انتشار ممارسات ومعتقدات تشويه الأعضاء التناسلية للإناث وارتباطاتها في غرب أفريقيا.

الطريقة

تم استخدام البيانات المستقاة من السيدات اللاتي استجبن للمسوح العنقودية متعددة المؤشرات التي أجريت فيما بين عامي 2005 و2007 لتقييم معدلات تواتر إجراء الختان، وإجبار البنات على الختان، والاعتقاد في ضرورة مواصلة ممارسات تشويه الأعضاء التناسلية للإناث. تم إجراء الارتداد اللوجستي المرجَّح باستخدام البيانات الخاصة بكل بلد لتحديد الارتباطات المستقلة لكل نتيجة.

النتائج

كان معدل انتشار تشويه الأعضاء التناسلية للإناث مرتفعًا بشكل عام ولكنه كان متنوعًا بشكل كبير فيما بين بلدان غرب أفريقيا. ففي سيراليون وغامبيا وبوركينا فاسو وموريتانيا، كانت نسبة انتشار تشويه الأعضاء التناسلية للإناث 94%، و79%، و74%، و72% على التوالي، بينما كانت نسبة الانتشار في غانا والنيجر وتوغو أقل من 6%. وارتبطت زيادة احتمالات تشويه الأعضاء التناسلية للإناث بالفئات العمرية الأكبر والمسلمة، وارتبط انخفاض احتمالات تشويه الأعضاء التناسلية للإناث بالتعليم العالي. وتنوع الارتباط بين تشويه الأعضاء التناسلية والثروة بشكل ملحوظ. وكانت بوركينا فاسو البلد الوحيدة في دراستنا التي شهدت انخفاضًا هائلاً في انتشار تشويه الأعضاء التناسلية للإناث من السيدات (74%) إلى بناتهن (25%)؛ وذكرت نسبة 14.2% فقط من السيدات اللاتي أُجري عليهن المسح في هذا البلد أنهن يؤمن بضرورة الاستمرار في هذه الممارسة.

الاستنتاج

يظل انتشار تشويه الأعضاء التناسلية للإناث في غرب أفريقيا مرتفعًا بشكل عام، ولكنه يتنوع بشكل كبير فيما بين البلدان. وفي ضوء النطاق الشاسع من التجارب والاستراتيجيات الناجحة المستقاة من البلدان التي ينخفض بها تشويه الأعضاء التناسلية للإناث، يمكن تقديم نماذج مفيدة للبلدان ذات نسبة الانتشار المرتفعة التي تسعى لخفض ممارسات تشويه الأعضاء التناسلية للإناث بها.

摘要

目的

开展西非女性生殖器割礼 (FGC) 习俗和信仰的普及率和相关性的跨国比较研究。

方法

使用参与 2005 至 2007 年多指标群体调查的女性的回答数据评估女性曾经被割除阴蒂的频率、曾经有一个女儿被割除阴蒂的频率以及认为应延续 FGC 习俗的频率。通过执行使用每个国家数据的加权逻辑回归方法确定每个结果的非依赖关系。

结果

西非整体 FGC 普及率高,但各个国家差别显著。在塞拉利昂、冈比亚、布基纳法索和毛里塔尼亚,FGC 的普及率分别为 94%、79%、74% 和 72%,而在加纳、尼日尔和多哥,普及率不到 6%。年纪更大且信奉穆斯林的群体一般会有更高的 FGC 比率,而接受高等教育的群体则表现为更低的 FGC 比率。FGC 和财富之间的关联差异很大。在我们的研究中,布基纳法索是唯一出现从女性 (74%) 到其女儿一辈 (25%) FGC 普及率显著降低的国家;该国家接受调查的女性仅 14.2% 认为应延续此习俗。

结论

西非国家整体上依然普遍施行 FGC,但各个国家差别很大。就大范围经验而言,FGC 比率降低的国家的成功战略可以作为高 FGC 普及率国家降低其本国 FGC 习俗普及率的有用范例。

Резюме

Цель

Провести межгосударственное сравнительное исследование распространенности и соотношения практики женского обрезания и связанных с данной практикой верований в Западной Африке.

Методы

Данные о женщинах, принявших участие в кластерных исследованиях с множественными показателями в период с 2005 по 2007 гг., были использованы для оценки частоты проведения обрезания среди самих женщин, среди их дочерей, и полагающих, что практика женского обрезания должна быть продолжена. Для определения независимых соотношений по каждому результату была применена средневзвешенная логистическая регрессия с использованием данных по каждой стране.

Результаты

Распространенность женского обрезания, в общем и целом, была высокой, но существенно варьировалась по странам в Западной Африке. В Сьерра-Леоне, Гамбии, Буркина Фасо и Мавритании распространенность женского обрезания равна 94%, 79%, 74% and 72%, соответственно, в то время как в Гане, Нигере и Того его распространенность составляет менее 6%. В основном, с увеличенной вероятностью женского обрезания ассоциировались более старший возраст и мусульманство, а высшее образование ассоциировалось с меньшей вероятностью женского обрезания. Связь между женским обрезанием и уровнем достатка значительно варьировалась. Буркина Фасо была единственной страной в нашем исследовании, в которой наблюдается значительное снижение распространенности женского обрезания от женщин (74%) к их дочерям (25%); только 14,2% женщин, участвовавших в исследовании в этой стране, высказались за продолжение данной практики.

Вывод

В целом распространенность женского обрезания в Западной Африке остается высокой, но существенно отличается по странам. Учитывая широкий спектр накопленного опыта, успешная стратегия стран, в которых распространенность женского обрезания снижается, может послужить в качестве полезного примера для стран с высокой степенью распространенности женского обрезания, стремящихся сократить данную практику в своих странах.

Introduction

More than 100 million girls and women have undergone female genital cutting (FGC, also known as “female circumcision”), and more than 3 million female infants and children are at risk for this procedure annually.1–3 FGC is seen as a rite of passage for young girls in some communities and is most often performed between the ages of 4 and 10.1,4 Reasons for this practice include beliefs that it enhances fertility, promotes purity, increases marriage opportunities and prevents stillbirths. These beliefs are strongly rooted in tradition, culture and religion, but none carries a scientific basis.5–8 Young girls and women who undergo FGC are subjected to extreme pain, since the procedure is often conducted without anaesthesia and under non-sterile conditions. When accompanied by excessive bleeding, it can even lead to death.9,10 Additional complications can include localized infection and abscess formation, pelvic infection, sepsis, tetanus, urinary retention and chronic urinary tract infection, hepatitis and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.11 Other reproductive health complications can include obstructed menstruation, difficulty conceiving, prolonged labour, tearing of tissues during delivery and neonatal death.8,11–16 Psychiatric sequelae such as flashbacks to the event, affective disorders and post-traumatic stress disorders can also affect women throughout their lives.8,12,13

Despite the risks associated with FGC, the peer-reviewed literature on the prevalence and predictors of FGC is sparse. Studies from Egypt and Ethiopia give FGC prevalences of approximately 85% and 70%, respectively,17,18 and several qualitative and anthropological studies have examined the underlying context for FGC.6,19–22 No studies, however, have reported cross-national comparisons of the prevalence of FGC and of the factors with which it is associated. Such data would be helpful for understanding the variation in the frequency of FGC, particularly in western Africa, where the practice is known to be common despite legislation and other efforts to curb its prevalence. Western Africa is also particularly well suited for cross-national comparisons because substantial differences exist between countries in prevalence rates and in the approaches used to eliminate this practice. These differences can bring to light potential strategies that may be useful in similar settings.

Accordingly, we sought to estimate the prevalence of FGC practices and beliefs across all western African countries for which national data were available from the most recent round of the Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS). We also aimed to identify correlates of these practices and beliefs to identify high-risk subpopulations. This evidence may be useful to help better understand country-level variation in this persistent but widely criticized practice1,23,24 and to target efforts to rid future generations of the practice of FGC in western Africa.

Methods

Study design and sample

We conducted a cross-sectional study of 10 countries in western Africa using self-reported data collected between the years 2005 and 2007 during the third round of the Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS). Data were available for Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Sierra Leone and Togo. Surveys were conducted in French in all countries except Gambia, Ghana, Nigeria and Sierra Leone, where they were conducted in English.

The MICS is a household survey developed by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) to provide national estimates of health indicators for women, men and children. The third round of the MICS used a two-stage stratified sample design in which enumeration areas were selected first, stratified by administrative region and area type (urban/rural). Households were systematically sampled from each enumeration area. Total sample size varied by country. The MICS used three sets of questionnaires, including a women’s self-reporting questionnaire administered face to face to all women in each household between the ages of 15 and 49 years.25

Measures

We examined three primary outcome measures. First, participants were asked “Have you yourself ever been circumcised?” (yes/no). Second, participants with at least one living daughter were asked “Have any of your daughters been circumcised? If yes, how many?” Responses indicated the number of daughters circumcised. For analysis, this variable was dichotomized into yes (at least 1 daughter circumcised) versus no (no daughters circumcised). Participants who had not heard of FGC or female circumcision (women who responded no to both “Have you ever heard of female circumcision?” and “In a number of countries, there is a practice in which a girl may have part of her genitals cut. Have you ever heard about this practice?”) were assumed to have not been circumcised and to have not had their daughters circumcised and were coded accordingly. Third, participants were asked “Do you think this practice should be continued?” (yes/depends/no). For analysis, this third variable was collapsed into two categories: yes/depends versus no. Participants who had not heard of FGC were coded as missing for this outcome.

Our independent variables included basic sociodemographic characteristics that were available across all countries, including age (5-year age groups), educational level (none, primary, above primary), marital status (currently married, formerly married, never married), wealth quintile and religion (Muslim versus non-Muslim). Subgroups of non-Muslims were examined for differential effects. Wealth quintiles were derived by the MICS using a combination of reported household assets and utility services.26

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed separately for each country. We first generated weighted frequencies to determine the prevalence of the three outcomes and to describe the characteristics of the sample populations. We then examined the potential for multicollinearity among the independent variables by using an average threshold correlation coefficient of 0.50. We constructed logistic regression models for each outcome, including all sociodemographic characteristics, whether or not they significantly contributed to the model. This approach was used to ensure the comparability of the models across countries. Because not all circumcised women are aware of having undergone circumcision, particularly if they have smaller incisions or were circumcised in infancy, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by repeating all analyses without including those respondents who reported never having heard of FGC, and we compared these results with our other findings. In all models we accounted for sample weighting and complex survey designs by adjusting for strata and cluster membership. Cases with missing data (< 5%) were excluded from the analyses, which were completed with SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, United States of America).

Results

Sample characteristics

On average, slightly more than half of the women in each sample were between the ages 15 and 29 (Table 1). More than half of the women in Burkina Faso, Côte d’ Ivoire, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Niger and Sierra Leone had had no formal education. In most countries, the majority of women were currently married, and the proportion of Muslims per country ranged from 14% to 99%.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics (weighted data) of women surveyeda in 10 western African countries, 2005–2007.

| Characteristic | Sierra Leone (n = 9 381) (%) |

Gambia (n = 9 982) (%) |

Burkina Faso (n = 7 316) (%) |

Mauritania (n = 12 549) (%) |

Guinea-Bissau (n = 8 010) (%) |

Côte d'Ivoire (n = 12 888) (%) |

Nigeria (n = 24 566) (%) |

Togo (n = 6 211) (%) |

Ghana (n = 5 890) (%) |

Niger (n = 9 223) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| 15–19 | 14.4 | 22.9 | 20.3 | 21.7 | 21.8 | 22.5 | 17.2 | 18.2 | 20.7 | 18.6 |

| 20–24 | 15.3 | 20.3 | 16.8 | 20.8 | 20.8 | 20.0 | 17.5 | 16.8 | 18.3 | 17.9 |

| 25–29 | 23.3 | 19.2 | 18.3 | 15.1 | 18.9 | 17.9 | 20.2 | 19.4 | 16.8 | 19.4 |

| 30–34 | 15.4 | 13.5 | 14.4 | 13.9 | 13.0 | 12.8 | 16.2 | 14.8 | 13.2 | 14.7 |

| 35–39 | 16.4 | 10.5 | 12.2 | 12.0 | 11.4 | 10.9 | 12.8 | 14.5 | 12.7 | 12.6 |

| 40–44 | 9.3 | 8.2 | 10.1 | 9.1 | 7.8 | 9.9 | 9.2 | 9.2 | 9.8 | 9.6 |

| 45–49 | 5.9 | 5.4 | 7.9 | 7.3 | 6.3 | 6.0 | 6.8 | 7.2 | 8.6 | 7.1 |

| Educational level | ||||||||||

| None | 73.9 | 54.0 | 75.4 | 23.5 | 57.7 | 53.0 | 40.7 | 38.6 | 26.3 | 83.5 |

| Primary | 11.0 | 11.8 | 13.6 | 32.7 | 26.5 | 27.1 | 19.0 | 34.2 | 19.7 | 10.4 |

| Beyond primary | 15.1 | 27.3 | 11.0 | 20.4 | 15.9 | 19.9 | 40.3 | 26.9 | 53.9 | 6.1 |

| Non-standard/Madrasab | – | 7.0 | – | 23.4 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Marital status | ||||||||||

| Never married | 14.7 | 26.8 | 20.6 | 28.4 | 29.0 | 38.5 | 25.9 | 25.4 | 30.2 | 9.9 |

| Currently married | 79.5 | 68.6 | 75.3 | 58.6 | 65.0 | 40.1 | 70.2 | 66.1 | 58.8 | 86.1 |

| Formerly married | 5.8 | 4.6 | 4.1 | 13.0 | 6.1 | 21.4 | 3.9 | 8.5 | 11.0 | 4.0 |

| Wealth quintile | ||||||||||

| Lowest | 19.4 | 17.1 | 17.7 | 17.8 | 18.7 | 17.6 | 18.1 | 15.7 | 16.2 | 19.0 |

| Second | 20.3 | 19.0 | 19.0 | 17.5 | 17.9 | 17.3 | 18.6 | 17.0 | 17.6 | 19.3 |

| Middle | 19.8 | 20.2 | 19.3 | 18.8 | 18.6 | 18.7 | 18.8 | 17.9 | 19.5 | 19.0 |

| Fourth | 19.7 | 21.4 | 19.7 | 22.0 | 20.3 | 21.2 | 20.8 | 23.6 | 22.0 | 20.7 |

| Highest | 20.7 | 22.3 | 24.4 | 23.9 | 24.6 | 25.2 | 23.7 | 25.8 | 24.6 | 22.0 |

| Religion | ||||||||||

| Non-Muslim | 21.1 | 3.8 | 37.7 | NA | 56.1 | 64.4 | 53.0 | 86.5 | 84.7 | 2.4 |

| Muslim | 77.9 | 96.2 | 62.3 | NA | 43.9 | 35.6 | 47.0 | 13.5 | 15.3 | 98.6 |

NA, not available.

a In third round of Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys.

b Non-standard education in Gambia and Madrasa education/Koranic school in Mauritania were included in the analysis because of the high percentages of women who selected these categories.

Country prevalence

The prevalence of FGC was high overall but varied substantially between countries. In Sierra Leone, Gambia, Burkina Faso and Mauritania, prevalence rates for FGC were 94%, 79%, 74% and 72%, respectively (Table 2). In contrast, fewer than 6% of women had been circumcised in Ghana, Niger and Togo. Gambia and Mauritania had the highest percentage of daughters circumcised (64%) and Togo, Ghana and Niger had the lowest (1%). In three countries, more than half of the women believed that the practice of FGC should continue (Sierra Leone, 88%, Gambia, 77% and Mauritania, 59%). The lowest percentages of women believing the practice should continue were found in countries with the lowest reported rates of FGC: Ghana (4%) and Niger (7%). Prevalence estimates after excluding women who had never heard of FGC remained largely unchanged.

Table 2. Female genital cutting (circumcision) practices (weighted data) as reported by women surveyeda in 10 western African countries, 2005–2007.

| Country | Had been circumcised (%) | Had had one or more daughters circumcised (%) | Believed practice should continueb (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sierra Leone | 94.0 | 34.9 | 88.1 |

| Gambia | 78.5 | 64.4 | 76.7 |

| Burkina Faso | 73.7 | 24.8 | 14.2 |

| Mauritania | 72.2 | 64.2 | 59.0 |

| Guinea-Bissau | 44.6 | 33.3 | 36.7 |

| Côte d’Ivoire | 36.5 | 20.9 | 26.7 |

| Nigeria | 26.0 | 13.3 | 31.0 |

| Togo | 5.8 | 1.0 | 11.4 |

| Ghana | 3.8 | 1.3 | 3.7 |

| Niger | 2.2 | 0.9 | 6.6 |

a In third round of Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys.

b Percentages include both yes and depends responses.

Associated sociodemographic characteristics

In general, being older, having less education, and being currently or formerly married as opposed to never married were all associated with increased odds of having been circumcised (Table 3, available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/90/2/11-090886). However, the opposite effects were seen in Gambia, where being older was associated with lower odds of having been circumcised and no association was noted between having been circumcised and educational level. Furthermore, being Muslim was generally associated with increased odds of having been circumcised. Effects across non-Muslim subgroups were largely similar, and the non-Muslim reference category was therefore maintained for analysis. The association between wealth and FGC varied across samples. In five countries greater wealth was associated with increased odds of having been circumcised; in the other five, less wealth was associated with increased odds of having been circumcised.

Table 3. Odds ratios (ORs) for having undergone female genital cutting (circumcision), by sociodemographic characteristics, for women surveyeda in 10 western African countries, 2005–2007.

| Characteristic | Sierra Leone (n = 7 631) OR (95% CI) |

Gambia (n = 9 926) OR (95% CI) |

Burkina Faso (n = 7 199) OR (95% CI) |

Mauritania (n = 12 498) OR (95% CI) |

Guinea-Bissau (n = 7 882) OR (95% CI) |

Côte d'Ivoire (n = 12 707) OR (95% CI) |

Nigeria (n = 24 207) OR (95% CI) |

Togo (n = 6 189) OR (95% CI) |

Ghana (n = 5 881) OR (95% CI) |

Niger (n = 9 164) OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| 15–19 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 20–24 | 2.06** (1.50–2.83) |

0.83* (0.70–0.98) |

1.20 (0.93–1.54) |

1.08 (0.93–1.25) |

1.14 (0.83–1.57) |

1.11 (0.92–1.33) |

1.27** (1.07–1.51) |

1.47 (0.82–2.64) |

1.25 (0.64–2.48) |

1.03 (0.65–1.64) |

| 25–29 | 2.15** (1.52–3.05) |

0.74** (0.60–0.92) |

1.30* (1.03–1.63) |

1.17 (0.97–1.41) |

1.25 (0.82–1.90) |

1.13 (0.91–1.40) |

1.59** (1.33–1.91) |

2.66** (1.44–4.91) |

0.97 (0.48–1.96) |

1.81* (1.04–3.15) |

| 30–34 | 2.29** (1.57–3.32) |

0.75* (0.60–0.94) |

1.73** (1.40– 2.14) |

1.17 (0.94–1.44) |

0.95 (0.64–1.42) |

1.25* (1.00–1.55) |

1.90** (1.56–2.33) |

3.37** (1.90–6.00) |

2.01 (0.89–4.54) |

1.83* (1.03–3.26) |

| 35–39 | 2.89** (1.83–4.57) |

0.80 (0.63–1.01) |

2.05** (1.61–2.62) |

1.24 (0.97–1.59) |

1.46 (0.95–2.23) |

1.25 (0.97–1.62) |

2.20** (1.82–2.67) |

4.33** (2.43–7.70) |

2.05 (0.95–4.45) |

2.61** (1.41–4.82) |

| 40–44 | 2.40** (1.37–4.22) |

0.65** (0.50–0.83) |

2.54** (1.96–3.29) |

1.35* (1.06–1.71) |

1.01 (0.63–1.63) |

1.09 (0.83–1.42) |

2.90** (2.34–3.61) |

5.20** (2.76–9.77) |

1.78 (0.78–4.03) |

2.79** (1.47–5.30) |

| 45–49 | 2.15* (1.18–3.92) |

0.58** (0.42–0.78) |

2.34** (1.75–3.12) |

1.36* (1.05–1.77) |

1.17 (0.74–1.86) |

1.07 (0.80–1.43) |

4.41** (3.48–5.58) |

5.24** (2.59–10.57) |

2.70* (1.16–6.28) |

2.33* (1.18–4.60) |

| Educational level | ||||||||||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Primary | 0.52** (0.38–0.71) |

1.02 (0.75–1.38) |

1.13 (0.93–1.37) |

0.68** (0.56–0.82) |

0.52** (0.39–0.71) |

0.46** (0.38–0.57) |

3.75** (3.17–4.45) |

0.44** (0.31–0.63) |

0.56** (0.39–0.81) |

0.76 (0.40–1.45) |

| Beyond primary | 0.44** (0.33–0.60) |

0.88 (0.72–1.07) |

0.97 (0.62–1.53) |

0.56** (0.45–0.71) |

0.20** (0.11–0.34) |

0.38** (0.31–0.48) |

3.85** (3.19–4.64) |

0.46** (0.28–0.77) |

0.21** (0.12–0.35) |

0.21** (0.07–0.66) |

| Non-standard/Madrasab | – | 1.17 (0.53– 2.58) |

– | 0.57** (0.45, 0.72) |

– | – | – | – | – | – |

| Marital status | ||||||||||

| Never married | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Currently married | 3.53** (2.63–4.73) |

1.28* (1.05–1.56) |

1.55** (1.26–1.92) |

1.35** (1.15–1.57) |

0.86 (0.59–1.24) |

2.04** (1.68–2.47) |

1.18* (1.02–1.37) |

2.35* (1.24–4.47) |

1.37 (0.69–2.72) |

0.47* (0.26–0.88) |

| Formerly married | 3.49** (2.14–5.69) |

1.35 (0.99–1.84) |

1.74** (1.21–2.51) |

1.25* (1.03–1.52) |

1.06 (0.64–1.77) |

1.01 (0.82–1.25) |

1.26 (0.99–1.61) |

2.00 (0.98–4.08) |

0.78 (0.34–1.80) |

0.54 (0.19–1.50) |

| Wealth quintile | ||||||||||

| Lowest | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Second | 0.44** (0.27–0.73) |

2.20** (1.53–3.18) |

1.35* (1.06–1.71) |

0.34** (0.25–0.47) |

1.55** (1.20–2.01) |

0.44** (0.31–0.63) |

2.03** (1.58–2.62) |

1.12 (0.71–1.75) |

1.12 (0.69–1.82) |

1.93* (1.00–3.69) |

| Middle | 0.54* (0.32–0.94) |

2.22** (1.42–3.47) |

0.96 (0.77–1.20) |

0.13** (0.10–0.19) |

2.36** (1.67–3.35) |

0.41** (0.27–0.62) |

2.65** (1.96–3.59) |

0.89 (0.54–1.45) |

0.47* (0.25–0.87) |

1.86 (0.75–4.59) |

| Fourth | 0.34** (0.20–0.59) |

1.68* (1.08–2.64) |

1.60** (1.22–2.08) |

0.06** (0.04–0.09) |

2.31** (1.61–3.31) |

0.36** (0.23–0.55) |

4.11** (3.08–5.49) |

0.81 (0.47–1.40) |

0.27** (0.13–0.55) |

5.87** (3.15–10.94) |

| Highest | 0.22** (0.13–0.38) |

0.74 (0.48–1.13) |

1.66** (1.22–2.25) |

0.04** (0.03–0.06) |

1.11 (0.73–1.70) |

0.26** (0.17–0.41) |

2.83** (2.10–3.80) |

0.40** (0.22–0.72) |

0.40* (0.18–0.89) |

3.04** (1.42–6.51) |

| Religion | ||||||||||

| Non-Muslim | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Muslim | 2.01** (1.55–2.60) |

16.56** (11.09–24.73) |

1.87** (1.45–2.41) |

NA | 218.97**,c (158.69–302.15) |

7.22** (5.49–9.50) |

0.56** (0.46–0.68) |

26.90** (18.01–40.18) |

4.38** (2.52–7.63) |

0.03** (0.01–0.12) |

CI, confidence interval; NA, not available; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

a In third round of Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys.

b Non-standard education in Gambia and Madrasa education/Koranic school in Mauritania were included in the analysis due to the high percentages of women who selected these categories; as a result, education for Gambia and Mauritania was modelled as dummy variables instead of the ordinal sequence used for other countries.

c OR estimate is large due to low frequencies of non-Muslims having ever been circumcised and low frequencies of Muslims not having ever been circumcised.

Being older, having less education and being Muslim were associated with higher odds of having had a daughter circumcised (Table 4, available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/90/2/11-090886). Wealth was inconsistently associated with having had a daughter circumcised; these associations were similar to those seen for having been circumcised. Finally, in most countries believing that the practice of FGC should continue was associated with being younger, having less education, being currently married and being poorer (Table 5, available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/90/2/11-090886). The associations between sociodemographic characteristics and outcomes were largely unaffected by excluding from the analysis those women who had never heard of FGC.

Table 4. Odds ratios (ORs) for having had at least one daughter undergo female genital cutting (circumcision), by sociodemographic characteristics, for women surveyed with at least one daughtera in 10 western African countries, 2005–2007.

| Characteristic | Sierra Leone (n = 4 970) OR (95% CI) |

Gambia (n = 5 321) OR (95% CI) |

Burkina Faso (n = 4 518) OR (95% CI) |

Mauritania (n = 6 598) OR (95% CI) |

Guinea-Bissau (n = 4 706) OR (95% CI) |

Côte d'Ivoire (n = 5 791) OR (95% CI) |

Nigeria (n = 12 880) OR (95% CI) |

Togo (n = 3 431) OR (95% CI) |

Ghana (n = 3 099) OR (95% CI) |

Niger (n = 6 148) OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| 15–19 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 20–24 | 0.90 (0.45–1.78) |

1.25 (0.91–1.71) |

1.86 (0.52–6.63) |

1.55* (1.11–2.17) |

2.09** (1.28–3.42) |

1.16 (0.58–2.29) |

0.72 (0.37–1.39) |

Excludedb | 0.78 (0.06–9.80) |

Excludedc |

| 25–29 | 2.21* (1.19–4.10) |

2.37** (1.74–3.23) |

4.54* (1.38–14.90) |

2.02** (1.45–2.80) |

4.66** (2.90–7.49) |

1.47 (0.78–2.80) |

0.94 (0.52–1.71) |

– | 0.60 (0.06–6.06) |

– |

| 30–34 | 6.27** (3.40–11.56) |

3.86** (2.74–5.43) |

8.04** (2.38–27.18) |

2.00** (1.41–2.83) |

6.60** (3.99–10.93) |

2.67** (1.47–4.83) |

1.41 (0.76–2.61) |

– | 0.66 (0.09–5.10) |

– |

| 35–39 | 10.33** (5.67–18.82) |

4.84** (3.37–6.93) |

19.95** (6.07–65.52) |

2.54** (1.80–3.57) |

9.95** (5.86–16.89) |

4.60** (2.30–9.20) |

1.75 (0.95–3.23) |

– | 1.42 (0.17–11.66) |

– |

| 40–44 | 23.14** (12.39–43.23) |

4.89** (3.44–6.94) |

38.66** (11.48–130.18) |

2.67** (1.84–3.88) |

11.26** (6.51–19.48) |

6.59** (3.43–12.63) |

2.63** (1.44–4.79) |

– | 1.22 (0.17–8.69) |

– |

| 45–49 | 29.78** (15.90–55.78) |

4.41** (2.97–6.54) |

45.51** (13.72–150.90) |

3.13** (2.18–4.49) |

12.23** (6.92–21.62) |

6.43** (3.28–12.62) |

3.38** (1.85–6.16) |

– | 2.54 (0.36–18.10) |

– |

| Educational level | ||||||||||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | Excludedb | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Primary | 0.80 (0.63–1.03) |

0.79 (0.61–1.02) |

1.06 (0.79–1.43) |

0.60** (0.49–0.72) |

0.71* (0.52–0.97) |

0.44** (0.32–0.61) |

2.60** (2.05–3.29) |

– | 0.47 (0.17–1.34) |

0.51 (0.12–2.14) |

| Beyond primary | 0.60** (0.46–0.79) |

0.48** (0.39–0.59) |

0.42** (0.22–0.79) |

0.39** (0.30–, 0.51) |

0.21** (0.12–0.34) |

0.34** (0.15–0.77) |

2.10** (1.55–2.83) |

– | 0.18** (0.05–0.67) |

0.97 (0.26–3.71) |

| Non-standard/Madrasad | – | 1.35 (0.73–2.49) |

– | 0.63** (0.50–0.78) |

– | – | – | – | – | |

| Marital status | ||||||||||

| Never married | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | Excludedb | Excludede | Excludedc |

| Currently married | 93 (0.54–1.60) |

1.59 (1.00–2.54) |

5.61 (0.76–41.42) |

7.18** (4.49–11.48) |

1.97** (1.21–3.18) |

2.13** (1.57–2.89) |

0.92 (0.53–1.60) |

– | – | – |

| Formerly married | 1.18 (0.66–2.13) |

1.39 (0.83–2.32) |

4.83 (0.63–36.74) |

5.66** (3.47–9.24) |

1.58 (0.85–2.94) |

0.98 (0.67–1.43) |

0.97 (0.52–1.79) |

– | – | – |

| Wealth quintile | ||||||||||

| Lowest | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Second | 0.94 (0.76–1.16) |

1.74** (1.31–2.30) |

1.05 (0.82–1.33) |

0.37** (0.27–0.51) |

1.00 (0.69–1.44) |

0.57** (0.39–0.82) |

2.35** (1.62–3.41) |

1.18 (0.54–2.60) |

1.31 (0.73–2.33) |

1.57 (0.58–4.24) |

| Middle | 1.10 (0.90–1.34) |

1.77** (1.26–2.50) |

0.98 (0.72–1.32) |

0.15** (0.11–0.21) |

0.90 (0.62–1.31) |

0.55** (0.38–0.80) |

2.78** (1.83–4.21) |

0.44* (0.20–0.94) |

0.36 (0.11–1.16) |

0.72 (0.22–2.38) |

| Fourth | 0.94 (0.76–1.16) |

1.62* (1.12–2.35) |

1.29 (0.96–1.73) |

0.07** (0.05–0.10) |

0.87 (0.60–1.27) |

0.33** (0.22–0.49) |

5.03** (3.38–7.47) |

0.33 (0.10–1.05) |

0.36 (0.10–1.34) |

3.07** (1.33–7.06) |

| Highest | 1.03 (0.80–1.34) |

0.88 (0.62–1.26) |

1.66** (1.19–2.31) |

0.03** (0.03–0.05) |

0.55** (0.37–0.80) |

0.20** (0.13–0.30) |

3.10** (2.05–4.68) |

0.14** (0.03–0.58) |

0.19 (0.03–1.31) |

1.02 (0.30–3.51) |

| Religion | ||||||||||

| Non-Muslim | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Muslim | 1.38** (1.16–1.65) |

17.20** (9.70–30.51) |

1.51** (1.18–1.93) |

NA | 85.93**,f (57.39–128.67) |

3.92** (2.83–5.42) |

0.88 (0.67–1.15) |

19.06** (8.24–44.10) |

4.31** (2.18–8.50) |

0.27** (0.10–0.72) |

CI, confidence interval; NA, not available; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

a In third round of Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys.

b In Togo, there were no women in the 15 to 19 age category, in the “never married” category, or in the “above primary” or “non-standard education” categories. Based on the likelihood ratio test (P < 0.05), we chose to exclude age, marital status and education level and present the better fitting, more parsimonious model.

c In Niger, there were no women in the 15 to 19 age category or in the “never married” category who had had at least one daughter cut. Based on the likelihood ratio test (P < 0.05), we chose to exclude both age and marital status and present the better fitting, more parsimonious model.

d Non-standard education in Gambia and Madrasa education/Koranic school in Mauritania were included in the analysis due to the high percentages of women who selected these categories; as a result, education for Gambia and Mauritania was modelled as dummy variables instead of the ordinal sequence used for other countries.

e In Ghana, there were no women in the “never married” category who had had at least one daughter cut. Based on the likelihood ratio test (P < 0.05), we chose to exclude marital status and present the better fitting, more parsimonious model.

f OR estimate is large due to low frequencies of non-Muslims having been circumcised and low frequencies of Muslims having never been circumcised.

Table 5. Odds ratios (ORs) for believing the practice of female genital cutting (FGC) should continue,a by sociodemographic characteristics, for women who had heard of FGC in surveyb in 10 western African countries, 2005–2007.

| Characteristic | Sierra Leone (n = 7 380) OR (95% CI) |

Gambia (n = 9 770) OR (95% CI) |

Burkina Faso (n = 6 644) OR (95% CI) |

Mauritania (n = 11 392) OR (95% CI) |

Guinea-Bissau (n = 6 990) OR (95% CI) |

Côte d'Ivoire (n = 10 559) OR (95% CI) |

Nigeria (n = 12 706) OR (95% CI) |

Togo (n = 4 528) OR (95% CI) |

Ghana (n = 4 052) OR (95% CI) |

Niger (n = 2 979) OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| 15–19 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 20–24 | 0.90 (0.70–1.15) |

0.78** (0.65–0.93) |

0.80 (0.53–1.20) |

0.86 (0.74–1.01) |

0.80 (0.63–1.00) |

0.75** (0.62–0.92) |

0.94 (0.79–1.12) |

0.80 (0.51–1.25) |

0.72 (0.34–1.49) |

0.80 (0.43–1.51) |

| 25–29 | 0.92 (0.70–1.22) |

0.70** (0.58–0.84) |

0.59** (0.43–0.80) |

0.93 (0.79 –1.11) |

0.88 (0.66–1.18) |

0.62** (0.51 –0.76) |

0.88 (0.73–1.05) |

0.97 (0.61–1.56) |

1.22 (0.59–2.53) |

0.88 (0.43–1.79) |

| 30–34 | 1.06 (0.77–1.45) |

0.67** (0.54–0.83) |

0.49** (0.34–0.71) |

0.78** (0.65–0.94) |

0.85 (0.65–1.13) |

0.73** (0.59–0.91) |

0.79* (0.63–0.97) |

0.87 (0.53–1.44) |

0.98 (0.42–2.27) |

0.77 (0.39–1.51) |

| 35–39 | 1.15 (0.85–1.55) |

0.65** (0.52–0.82) |

0.66* (0.47–0.92) |

0.78* (0.64–0.94) |

1.20 (0.89–1.62) |

0.73** (0.58–0.92) |

0.87 (0.70–1.08) |

0.93 (0.58–1.48) |

0.53 (0.23–1.22) |

0.97 (0.45–2.12) |

| 40–44 | 1.31 (0.89–1.94) |

0.56** (0.44–0.72) |

0.60** (0.42–0.86) |

0.77* (0.62–0.95) |

1.01 (0.75–1.37) |

0.71** (0.56–0.91) |

0.97 (0.77–1.23) |

1.02 (0.60–1.75) |

0.85 (0.37–1.97) |

0.78 (0.34–1.81) |

| 45–49 | 1.85** (1.17–2.93) |

0.56** (0.42–0.76) |

0.61* (0.42–0.89) |

0.77* (0.62–0.97) |

0.91 (0.65–1.29) |

0.81 (0.60–1.10) |

1.22 (0.94–1.57) |

1.27 (0.74–2.18) |

0.32* (0.13–0.84) |

1.44 (0.67–3.10) |

| Educational level | ||||||||||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Primary | 0.79 (0.63–1.01) |

0.74* (0.58–0.95) |

0.89 (0.70–1.13) |

0.58** (0.50–0.68) |

0.43** (0.36–0.52) |

0.46** (0.39–0.56) |

1.40** (1.15–1.69) |

0.80 (0.59–1.09) |

0.56* (0.31–0.99) |

0.45** (0.25–0.80) |

| Above primary | 0.34** (0.27–0.42) |

0.50** (0.42–0.60) |

0.17** (0.11–0.26) |

0.36** (0.30–0.43) |

0.21** (0.16–0.28) |

0.22** (0.17–0.28) |

1.31** (1.08–1.59) |

0.50** (0.35–0.71) |

0.62 (0.38–1.04) |

0.25** (0.11–0.59) |

| Non-standard/Madrasab | – | 0.91 (0.44–1.88) |

– | 0.76** (0.64–0.91) |

– | – | – | – | – | – |

| Marital status | ||||||||||

| Never married | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Currently married | 1.44** (1.12–1.84) |

1.31** (1.09–1.56) |

1.03 (0.53–1.99) |

1.23** (1.06–1.42) |

1.45** (1.13–1.86) |

1.93** (1.58–2.37) |

1.14 (0.95–1.35) |

1.62* (1.04–2.51) |

1.80 (0.96–3.37) |

0.62 (0.32–1.20) |

| Formerly married | 1.12 (0.81–1.54) |

0.98 (0.75–1.29) |

0.76 (0.36–1.63) |

1.10 (0.92–1.32) |

1.18 (0.85–1.64) |

1.02 (0.81–1.28) |

1.14 (0.87–1.50) |

1.26 (0.69–2.32) |

0.96 (0.46–2.01) |

0.25** (0.09–0.67) |

| Wealth quintile | ||||||||||

| Lowest | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Second | 0.63 (0.38–1.03) |

1.60** (1.13–2.26) |

0.63** (0.47–0.83) |

0.50** (0.38–0.65) |

1.01 (0.79–1.28) |

0.60** (0.46–0.78) |

1.12 (0.85–1.48) |

0.62** (0.44–0.87) |

0.74 (0.43–1.27) |

0.85 (0.50–1.44) |

| Middle | 0.39** (0.24–0.64) |

1.52 (1.00–2.32) |

0.84 (0.64–1.11) |

0.23** (0.18–0.30) |

0.86 (0.66–1.12) |

0.51** (0.38–0.69) |

1.13 (0.84–1.53) |

0.57* (0.37–0.88) |

0.65 (0.36–1.17) |

0.72 (0.42–1.21) |

| Fourth | 0.20** (0.12–0.32) |

0.93 (0.61–1.40) |

0.76 (0.55–1.05) |

0.12** (0.09–0.15) |

0.63** (0.48–0.82) |

0.40** (0.29–0.56) |

1.26 (0.94–1.70) |

0.45** (0.30–0.70) |

0.34** (0.18–0.64) |

0.63 (0.37–1.08) |

| Highest | 0.15** (0.09–0.24) |

0.38** (0.26–0.56) |

0.86 (0.65–1.13) |

0.06** (0.05–0.08) |

0.33** (0.24–0.43) |

0.24** (0.17–0.34) |

0.79 (0.58–1.07) |

0.47** (0.30–0.73) |

0.22** (0.11–0.43) |

0.53* (0.31–0.93) |

| Religion | ||||||||||

| Non-Muslim | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Muslim | 1.60** (1.29–1.97) |

16.92** (10.75–26.64) |

1.75** (1.39–2.20) |

NA | 17.42** (13.82–21.96) |

3.12** (2.50–3.89) |

1.33** (1.11–1.61) |

0.92 (0.68–1.25) |

0.99 (0.59–1.68) |

0.62 (0.30–1.29) |

CI, confidence interval; NA, not available; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

a “Believing the practice should continue” includes both yes and depends responses.

b Third round of Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys.

c Non-standard education in Gambia and Madrasa education/Koranic school in Mauritania were included in the analysis due to the high percentages of women who selected these categories; as a result, education for Gambia and Mauritania was modelled as dummy variables instead of the ordinal sequence used for other countries.

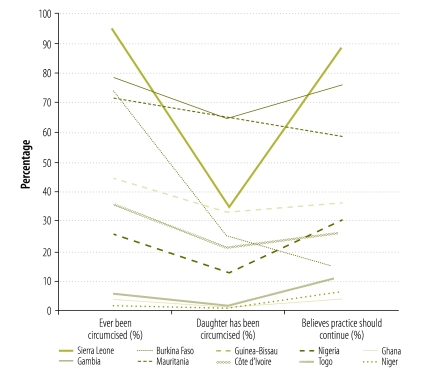

Comparisons across outcomes

Recognizing that the frequencies of our outcomes could represent changes in the prevalence of FGC over time, we plotted the data sequentially by country (Fig. 1). In all countries, the percentage of women who had their daughters circumcised was lower than the percentage who had themselves been circumcised. The relationship between believing that FGC should continue and having had a daughter circumcised was not consistent across countries. Burkina Faso and Mauritania were the only two countries where the percentage of women who believed that FGC should continue was lower than the percentage that had had their daughters circumcised.

Fig. 1.

Graphical depiction of prevalence for each outcome by countrya,b

FGC, female genital cutting; MICS, multiple indicator cluster surveys.

a Due to the proxy measure used to assess FGC in Sierra Leone, the MICS recommends not interpreting the estimate for believing that this practice should continue.27

b Percentages include both yes and depends responses.

Discussion

The estimated prevalence of FGC varied widely across countries, despite their geographic proximity, and this variation probably reflects the differences in political, social and historical contexts in countries where FGC is practiced. In Burkina Faso, Gambia, Mauritania and Sierra Leone more than 70% of women had been circumcised, whereas in Ghana, Niger and Togo less than 6% had been circumcised. Additionally, in four countries at least one third of the women reported having had their daughters circumcised, and in six countries more than 20% believed that FGC practices should continue despite recent public criticism of FGC. These findings are concerning, given the potential for causing a girl severe physical and psychological harm.

We also recognize that the prevalence of FGC can vary substantially within the same country. Our findings show that certain women belonging to certain subgroups based on educational level, wealth and religion have significantly increased rates of FGC. Such rates can also vary within countries depending on ethnicity and geographic region. Although these variables could have enhanced our analysis, they were excluded to maintain comparability across country models. For instance, reports of FGC are common in the southern regions of Nigeria but are substantially less frequent in its northern regions. Recognizing the diversity within countries in western Africa is particularly important for developing interventions and targeting efforts to reduce FGC.

Two countries – Burkina Faso and Mauritania – stand out for having succeeded in reducing FGC and support for this practice. This is evidenced by the fact that the percentages of women who have been circumcised, who report that their daughters have been circumcised, and who believe that FGC should continue have shown steady declines. Burkina Faso, for instance, has established the National Committee to Fight against the Practice of Excision, a government-led entity that seeks to make citizens aware of the dangers of FGC and to ensure that proper law enforcement is in place to convict people who continue the practice. Although several countries have passed legislation banning FGC, Burkina Faso is the only country in which people who break this law are commonly prosecuted.28,29 Mauritania has also experienced consistent declines in FGC and in support for the practice, although less dramatically than Burkina Faso. The government of Mauritania has established the Ministry of Women's Affairs (MCPFEF), which works with governmental groups as well as community and religious leaders to promote FGC awareness campaigns.30 Mauritania also has a law against “harm[ing] the genital organs of a female child". However, prosecution is rare.31 Diligence in prosecution could contribute to the differing rates of decline between Burkina Faso and Mauritania.

Based on the efforts and outcomes in both Burkina Faso and Mauritania, we postulate that four components are necessary for effectively reducing FGC practice and support. These include: (i) community education and awareness, (ii) the use of prominent groups to champion the cause, (iii) the support of FGC practitioners such as nurses, midwives, and traditional healers, and (iv) enforced legislation. First, community education and awareness can enable and facilitate affected communities to promote positive attitudes towards discontinuing the practice.5,32,33 Successful community strategies have been documented, including circumcision-free rite-of-passage ceremonies and collective declarations in which villages pledge not to circumcise their daughters.8 Second, strategies in Burkina Faso and Mauritania have used high-ranking women and a broad array of professionals and other influential people, such as government representatives and religious leaders to champion reform efforts.29,34 Third, the participation of FGC practitioners within each country are central to meaningful implementation of reform strategies by limiting access to FGC services and educating their patients.35,36 Last, enforced legislation is particularly critical; legislation alone, without broad-based political support and enforcement, is likely to be ineffective.37 Such concerted and multifaceted commitments allow for the preservation of a community’s cultural heritage and social values while sustaining attitude shifts away from FGC for the benefit of future generations of women and girls.

Our results suggest subpopulations in each country where efforts could be targeted. For instance, older ages were consistently associated with the practice of FGC. The FGC practices of older women may be a result of past societal norms, including pressure from family members or spouses, even if they did not support the practice. Conversely, younger ages were more likely to believe the practice should continue, possibly because many may not yet have had to consider circumcising their own daughter. When women are faced with the decision to circumcise their own daughters or have already done so, their support of FGC may diminish. Furthermore, these younger women may not have been circumcised themselves and are therefore able to support the practice more easily without having experienced the medical and psychological complications that many of the older women had. Being less educated and Muslim were also generally associated with all three of our outcomes, suggesting that these subpopulations may be important groups for intervention approaches in some countries. Correlates, however, were not always consistent across countries. FGC in Niger and Nigeria, for instance, was not associated with Muslim religion. Additionally, in some countries wealth was associated with higher odds of engaging in the practice, and in others it was associated with lower odds of engaging in the practice. These variations reiterate contextual differences and the importance of having country-specific data to effectively tailor approaches for reducing and eliminating the practice of FGC.

Strengths of this study include its role in filling a large and significant gap in the peer-reviewed literature. Given the risks to both the physical and mental health of girls and women who undergo FGC and the desperate need for more effective strategies to eliminate this practice, our research calls attention to the substantial prevalence in several countries and provides information for affected governments and communities. Furthermore, medical and public health professionals in western Africa can use these results to identify patient subpopulations with whom they may need to address FGC practices and beliefs. Through this cross-country comparison, we were also able to highlight potential approaches for effectively reducing and eliminating this complex and deeply rooted practice. We also generated the data needed to identify subgroups of women at high risk for FGC to ensure that these strategies may be effectively implemented.

Our results should be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, we used only sample characteristics that were available in all countries and those that were largely consistent across countries, limiting our ability to describe practicing communities further. Second, it is possible that FGC-related practices and attitudes may have changed since the time of data collection (2005–2007); however, we used the most recent round of data made available by the MICS for this region. Third, the data collected from Sierra Leone may not be as comparable to other data as we may have wished. Questions for Sierra Leone did not refer to female circumcision or genital cutting, but to initiation into the Bondo Society. This alternative phrasing was deemed most relevant to the practicing culture in Sierra Leone,27 although this measurement was markedly different from that used in other countries. Fourth, responses may be subject to social desirability or recall bias, depending on the cultural context and strategies in place to eliminate FGC. Women may have been motivated to underreport circumcision and their support for the practice, particularly in countries in which legislation exists against such behaviour. Although other approaches, such as medical record reviews or examinations,38 may have been more valid for measuring the prevalence of FGC, they were not feasible in these settings due to additional cost and time. As a result, these self-reported data across several countries were best for meeting our research objectives. Last, our analysis did not consider the type of FGC that had been experienced by the women in our samples. The type generally performed in each country, however, was not markedly different. Most of the countries in our sample perform a combination of Type I (clitoridectomy) and Type II (excision) or Type II only. It has been estimated that approximately 90% of all FGC includes these types where the flesh is either nicked or removed. Three countries in our sample (Gambia, Ghana, and Nigeria), however, perform the most severe form of FGC (Type III, infibulation) in at least some parts of the country. Infibulation, or being sewn shut, may describe up to 10% of all FGC.5,34,39 The countries where this type occurs, and these affected women, may warrant additional and increased efforts.

Although action against FGC must be tempered with an understanding of the deeply rooted traditions that have allowed this practice to continue for so many generations, effective approaches for reducing FGC are critical. Despite widespread efforts, prevalence remains high in many countries, putting millions of girls at risk every year. Successful strategies for eliminating FGC are likely to require multi-pronged approaches in which political, legal and cultural elements are choreographed to effect large-scale change. Such concerted societal commitments are necessary for the benefit of future generations of women and girls.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Bioethics Ritual genital cutting of female minors. Pediatrics. 2010;125:1088–93. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Female genital cutting: frequently asked questions Washington: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office on Women's Health; 2009. Available from: http://www.womenshealth.gov/faq/female-genital-cutting.cfm#f [accessed 14 October 2011].

- 3.Eliminating female genital mutilation: an interagency statement Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. Available from: http://www.unifem.org/attachments/products/fgm_statement_2008_eng.pdf [accessed 14 October 2011]

- 4.Toubia N. Female circumcision as a public health issue. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:712–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409153311106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nour NM. Female genital cutting: a persisting practice. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2008;1:135–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gruenbaum E. Socio-cultural dynamics of female genital cutting: research findings, gaps, and directions. Cult Health Sex. 2005;7:429–41. doi: 10.1080/13691050500262953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Shawarby SA, Rymer J. Female genital cutting. Obstetrics Gynaecol Reprod Med. 2008;18:253–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ogrm.2008.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tradition and rights: female genital cutting in West Africa Surrey: Plan; 2005. Available from: http://plan-international.org/where-we-work/africa/publications/tradition-and-rights-female-genital-cutting-in-west-africa [accessed 14 October 2011].

- 9.A systematic review of the health complications of female genital mutilation including sequelae in childbirth Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2000/WHO_FCH_WMH_00.2.pdf [accessed 14 October 2011].

- 10.Momoh C. Female genital mutilation. . Trends Urol Gynecol Sexual Health. 2010;15:11–4. doi: 10.1002/tre.142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Female genital mutilation and its management. Green-top Guideline 2009531–17.Available from: http://www.rcog.org.uk/files/rcog-corp/GreenTop53FemaleGenitalMutilation.pdf[accessed 17 January 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chibber R, El-Saleh E, El Harmi J. Female circumcision: obstetrical and psychological sequelae continues unabated in the 21st century. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;24:833–6. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2010.531318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elnashar A, Abdelhady R. The impact of female genital cutting on health of newly married women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;97:238–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nour NM. Female genital cutting: clinical and cultural guidelines. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2004;59:272–9. doi: 10.1097/01.OGX.0000118939.19371.AF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones H, Diop N, Askew I, Kaboré I. Female genital cutting practices in Burkina Faso and Mali and their negative health outcomes. Stud Fam Plann. 1999;30:219–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.1999.00219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banks E, Meirik O, Farley T, Akande O, Bathija H, Ali M, WHO study group on female genital mutilation and obstetric outcome Female genital mutilation and obstetric outcome: WHO collaborative prospective study in six African countries. Lancet. 2006;367:1835–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68805-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hassanin IM, Saleh R, Bedaiwy AA, Peterson RS, Bedaiwy MA. Prevalence of female genital cutting in Upper Egypt: 6 years after enforcement of prohibition law. Reprod Biomed Online. 2008;16:27–31. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60396-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rahlenbeck S, Mekonnen W, Melkamu Y. Female genital cutting starts to decline among women in Oromia, Ethiopia. Reprod Biomed Online. 2010;20:867–72. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fahmy A, El-Mouelhy MT, Ragab AR. Female genital mutilation/cutting and issues of sexuality in Egypt. Reprod Health Matters. 2010;18:181–90. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(10)36535-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kallon I, Dundes L. The cultural context of the Sierra Leonean Mende woman as patient. J Transcult Nurs. 2010;21:228–36. doi: 10.1177/1043659609358781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jirovsky E. Views of women and men in Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso, on three forms of female genital modification. Reprod Health Matters. 2010;18:84–93. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(10)35513-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mackie G. Ending footbinding and infibulation: a convention account. Am Sociol Rev. 1996;61:999–1017. doi: 10.2307/2096305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kmietowicz Z. UK colleges criticize US advice on female genital mutilation. BMJ. 2010;340:c2586. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mackie G. Female genital cutting: a harmless practice? Med Anthropol Q. 2003;17:135–58. doi: 10.1525/maq.2003.17.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Indicator Cluster M. Surveys/MICS3: background. New York: Statistics and Monitoring, Division of Policy and Practice, United Nations Children’s Fund; 2009. Available from: http://www.childinfo.org/mics3_background.html [accessed 14 October 2011]. [Google Scholar]

- 26.The DHS wealth index (Comparative Reports DHS 6). Calverton: Measure DHS+; 2004. Available from: http://www.childinfo.org/files/DHS_Wealth_Index_(DHS_Comparative_Reports).pdf [accessed 14 October 2011]

- 27.Sierra Leone Mulitple Indicator Cluster Survey 2005, final report Freetown: Statistics Sierra Leone & United Nations Children’s Fund – Sierra Leone; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burkina Faso: report on female genital mutilation (FGM) or female genital cutting (FGC) Washington: Office of the Senior Coordinator for International Women's Issues, Office of the Under Secretary for Global Affairs, U.S. Department of State; 2001. Available from: http://www.asylumlaw.org/docs/burkinafaso/usdos01_fgm_BurkinaFaso.pdf [accessed 14 October 2011]

- 29.Diop NJ, Congo Z, Ouedraogo A, Sawadogo A, Saloucou L, Tamini I. Analysis of the evolution of the practice of female genital mutilation/cutting in Burkina Faso (FRONTIERS final report). Washington: Population Council; 2008. Available from: http://www.popcouncil.org/pdfs/frontiers/FR_FinalReports/BurkinaFaso_FGMAnalysis.pdf [accessed 14 October 2011]

- 30.Female genital mutilation in Mauritania Echsborn: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ); 2007. Available from: http://www.gtz.de/de/dokumente/en-fgm-countries-mauritania.pdf [accessed 14 October 2011].

- 31.Netherlands Institute of Human Rights. Utrecht School of Law [Database]. Utrecht: NIHR; 2011. Available from: http://sim.law.uu.nl/SIM/CaseLaw/uncom.nsf/804bb175b68baaf7c125667f004cb333/4d361ae5e097d159c12573390044b2ec?OpenDocument [accessed 14 October 2011].

- 32.Afifi M. Egyptian ever-married women's attitude toward discontinuation of female genital cutting. Singapore Med J. 2010;51:15–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mackie G. Female genital cutting: the beginning of the end. In: Shell-Duncan B, Hernlund Y, editors. Female circumcision in Africa: culture, controversy and change Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers; 2000. pp. 253-81. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoder PS, Khan S. Numbers of women circumcised in Africa: the production of a total Calverton: Macro International Inc.; 2008. Available from: http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/WP39/WP39.pdf [accessed 14 October 2011]. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moore K, Randolph K, Toubia N, Kirberger E. The synergistic relationship between health and human rights: a case study using female genital mutilation. Health Hum Rights. 1997;2:137–46. doi: 10.2307/4065277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Female genital mutilation (Fact Sheet no. 241). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs241/en/ [accessed 14 October 2011].

- 37.Ako MA, Akweongo P. The limited effectiveness of legislation against female genital mutilation and the role of community beliefs in Upper East Region, Ghana. Reprod Health Matters. 2009;17:47–54. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(09)34474-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elmusharaf S, Ethadi N, Almroth L. Reliability of self reported form of female genital mutilation and WHO classification: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2006;333:124–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38873.649074.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dietrick HL. Introduction: FGC around the world The Female Genital Cutting Education and Networking Project; 2003. Available from: http://www.fgmnetwork.org/intro/world.php [accessed 14 October 2011]. [Google Scholar]