Abstract

Objective

To review the evidence about the prevalence and determinants of non-psychotic common perinatal mental disorders (CPMDs) in World Bank categorized low- and lower-middle-income countries.

Methods

Major databases were searched systematically for English-language publications on the prevalence of non-psychotic CPMDs and on their risk factors and determinants. All study designs were included.

Findings

Thirteen papers covering 17 low- and lower-middle-income countries provided findings for pregnant women, and 34, for women who had just given birth. Data on disorders in the antenatal period were available for 9 (8%) countries, and on disorders in the postnatal period, for 17 (15%). Weighted mean prevalence was 15.6% (95% confidence interval, CI: 15.4–15.9) antenatally and 19.8% (19.5–20.0) postnatally. Risk factors were: socioeconomic disadvantage (odds ratio [OR] range: 2.1–13.2); unintended pregnancy (1.6–8.8); being younger (2.1–5.4); being unmarried (3.4–5.8); lacking intimate partner empathy and support (2.0–9.4); having hostile in-laws (2.1–4.4); experiencing intimate partner violence (2.11–6.75); having insufficient emotional and practical support (2.8–6.1); in some settings, giving birth to a female (1.8–2.6), and having a history of mental health problems (5.1–5.6). Protective factors were: having more education (relative risk: 0.5; P = 0.03); having a permanent job (OR: 0.64; 95% CI: 0.4–1.0); being of the ethnic majority (OR: 0.2; 95% CI: 0.1–0.8) and having a kind, trustworthy intimate partner (OR: 0.52; 95% CI: 0.3–0.9).

Conclusion

CPMDs are more prevalent in low- and lower-middle-income countries, particularly among poorer women with gender-based risks or a psychiatric history.

Résumé

Objectif

Étudier la preuve de la prévalence et des déterminants des troubles mentaux périnataux communs (TMPC) non psychotiques dans les pays à revenu faible et moyen, selon les catégories de la Banque mondiale.

Méthodes

Des recherches systématiques ont été effectuées dans les principales bases de données afin de trouver des publications en anglais sur la prévalence des TMPC non psychotiques et sur leurs facteurs de risque et déterminants. Tous les protocoles d’études ont été inclus.

Résultats

Treize articles, couvrant 17 pays à revenu faible et moyen, ont fourni des résultats sur les femmes enceintes, et 34 sur les femmes qui venaient d’accoucher. Les données sur les troubles pendant la période prénatale étaient disponibles pour 9 pays (8%), et sur les troubles pendant la période postnatale pour 17 pays (15%). La prévalence moyenne pondérée était de 15,6% (intervalle de confiance de 95%, IC: 15,4–15,9) du point de vue prénatal, et de 19,8% (19,5–20,0) du point de vue postnatal. Les facteurs de risque étaient les suivants: des problèmes socioéconomiques (variation du rapport des cotes [RC]: 2,1–13,2); une grossesse non désirée (1,6–8,8); le fait d’être trop jeune (2,1–5,4); le fait de ne pas être mariée (3,4–5,8); le manque de soutien et d’empathie de la part du partenaire (2,0–9,4); des beaux-parents hostiles (2,1–4,4); un partenaire violent (2,11–6,75); un soutien émotionnel et pratique insuffisant (2,8–6,1); et dans certains cas, donner naissance à une fille (1,8–2,6) et avoir des antécédents de problèmes de santé mentale (5,1–5,6). Les facteurs protecteurs étaient les suivants: avoir fait plus d’études (risque relatif: 0,5; P = 0,03); avoir un emploi permanent (RC: 0,64; IC de 95%: 0,4–1,0); être issue de la majorité ethnique (RC: 0,2; IC de 95%: 0,1–0,8) et avoir un partenaire attentionné et digne de confiance (RC: 0,52; IC de 95%: 0,3–0,9).

Conclusion

Les TMPC ont une prévalence plus élevée dans les pays à revenu faible et moyen, en particulier chez les femmes plus pauvres présentant des antécédents psychiatriques ou des risques liés au genre.

Resumen

Objetivo

Examinar las pruebas clínicas acerca de la prevalencia y los determinantes de los trastornos mentales perinatales frecuentes (TMPF) no psicóticos en los países de ingresos bajos o medios-bajos según la clasificación del Banco Mundial.

Métodos

Se examinaron de forma sistemática bases de datos importantes en busca de publicaciones en inglés acerca de la prevalencia de TMPF no psicóticos, así como sus determinantes y factores de riesgo. Se incluyeron todos los diseños de estudios.

Resultados

Trece documentos que abarcaban 17 países de ingresos bajos y medios-bajos proporcionaron resultados para mujeres embarazadas, y 34, para mujeres que acababan de dar a luz. Existían datos acerca de los trastornos durante el periodo prenatal para 9 países (8%), y sobre los trastornos durante el periodo postnatal para 17 países (15%). La prevalencia media ponderada fue del 15,6% (intervalo de confianza [IC] del 95%: 15,4-15,9) en el periodo prenatal y del 19,8% (19,5-20,0) en el periodo postnatal. Los factores de riesgo fueron: desventajas socioeconómicas (razón de posibilidades [OR]: 2,1-13,2); embarazo no deseado (1,6-8,8); juventud de la madre (2,1-5,4); no estar casada (3,4-5,8); ausencia de empatía y apoyo por parte de la pareja (2,0-9,4); familia política hostil (2,1-4,4); sufrir violencia por parte de la pareja (2,11-6,75); apoyo emocional y práctico insuficiente (2,8-6,1); en algunos entornos, dar a luz a una niña (1,8-2,6), y tener antecedentes de problemas de salud mental (5,1-5,6). Los factores de protección fueron: mayor educación (riesgo relativo: 0,5; P=0,03); tener un trabajo estable (OR: 0,64; IC del 95%: 0,4-1,0); pertenecer a una mayoría étnica (OR: 0,2; IC del 95%: 0,1-0,8) y tener una pareja amable y de confianza (OR: 0,52; IC del 95%: 0,3-0,9).

Conclusión

Los TMPF presentan una prevalencia mayor en países con ingresos bajos y medios-bajos, en particular, entre las mujeres más pobres con riesgos relacionados con el género o con antecedentes psiquiátricos.

ملخص

الغرض

مراجعة الأدلة الخاصة بانتشار الاضطرابات النفسية الشائعة غير الذهانية أثناء الفترة المحيطة بالولادة ومحدداتها (CPMDs) في البلدان منخفضة الدخل والبلدان ذات الشريحة الدنيا من الدخل المتوسط وفق تصنيف البنك الدولي.

الطريقة

تم إجراء بحث منهجي في قواعد البيانات الرئيسية للمطبوعات باللغة الإنجليزية حول انتشار الاضطرابات النفسية الشائعة غير الذهانية أثناء الفترة المحيطة بالولادة وعوامل الخطر ومحدداتها. تم تضمين كافة تصميمات الدراسة.

النتائج

قدمت ثلاثة عشر بحثًا تغطي 17 بلدًا من البلدان منخفضة الدخل والبلدان ذات الشريحة الدنيا من الدخل المتوسط نتائج خاصة بالسيدات الحوامل، وقدمت 34 بحثًا نتائج خاصة بالسيدات اللاتي وضعن للتو. وكانت البيانات الخاصة بالاضطرابات في الفترة السابقة للولادة متوفرة لتسعة بلدان (8%) والخاصة بالاضطرابات في الفترة اللاحقة للولادة متوفرة لسبعة عشر بلدًا (15%). وبلغ متوسط الانتشار المرجَّح 15.6% (فترة الثقة 95%، فترة الثقة: 15.4 - 15.9) قبل الولادة و19.8% (19.5–20.0) بعد الولادة. وتمثلت عوامل الخطر في: العيوب الاجتماعية والاقتصادية (نسبة الاحتمال [أو] النطاق: 2.1 - 13.2)؛ والحمل غير المرغوب فيه (1.6 - 8.8)؛ وصغر السن (2.1 - 5.4)؛ وعدم الزواج (3.4 - 5.8)؛ والافتقار إلى الدعم والتعاطف من جانب شريك الحياة (2.0 - 9.4)؛ والأصهار العدائيين (2.1–4.4)؛ والمعاناة من عنف شريك الحياة (2.11 - 6.75)؛ وعدم كفاية الدعم العملي والعاطفي (2.8 - 6.1)؛ وولادة مولود أنثى، في بعض البيئات (1.8 - 2.6) ووجود تاريخ من مشكلات الصحة النفسية (5.1 - 5.6). وتمثلت عوامل الحماية في: زيادة التعليم (المخاطر النسبية: 0.5؛ الاحتمالية = 0.03)؛ والعمل في وظيفة دائمة (أو: 0.64، 95%، فترة الثقة: 0.4 - 1.0)؛ والانتماء إلى الأغلبية العرقية (أو: 0.2، 95%، فترة الثقة: 0.1 - 0.8)؛ ووجود شريك حميم عطوف وجدير بالثقة (أو: 0.52، 95%، فترة الثقة: 0.3 - 0.9).

الاستنتاج

الاضطرابات النفسية الشائعة أثناء الفترة المحيطة بالولادة (CPMDs) أكثر انتشارًا في البلدان منخفضة الدخل والبلدان ذات الشريحة الدنيا من الدخل المتوسط، وبالأخص بين السيدات الأكثر فقرًا اللاتي يتعرضن لمخاطر على أساس نوع الجنس أو ذوات تاريخ من المرض النفسي.

摘要

目的

综述按照世界银行分类的低收入和中低收入国家的非精神病常见围产期精神障碍 (CPMD) 的患病率和决定因素有关的证据。

方法

系统地搜索主要数据库中有关非精神病 CPMD 患病率及其风险因素和决定因素的英语出版物。包括所有研究设计。

结果

十三篇涉及论文提供了 17 个低收入和中低收入国家针对孕妇的结果和34 个国家针对刚刚分娩的女性的结果。可获得产前障碍数据的国家有 9 (8%) 个,可获得产后障碍数据的国家有 17 (15%) 个。产前加权平均患病率为 15.6% (95% 置信区间,CI:15.4–15.9),产后为 19.8% (19.5–20.0)。风险因素为:社会经济弱势(比值比 [OR] 范围:2.1–13.2);意外怀孕 (1.6–8.8);年纪较轻 (2.1–5.4);未婚 (3.4–5.8);缺乏亲密伴侣同理心和支持 (2.0–9.4);难以相处的姻亲 (2.1–4.4);遭遇亲密伴侣暴力 (2.11–6.75);情感和实际支持不够 (2.8–6.1);在某些情况下,生出女婴 (1.8–2.6) 和有精神健康问题史 (5.1–5.6)。防护因素为:受过更多教育(相对风险:0.5;P = 0.03);有稳定工作(OR:0.64;95% CI:0.4–1.0);属于人口多数民族(OR:0.2;95% CI:0.1–0.8)和拥有善良可靠的亲密伴侣(OR:0.52;95% CI:0.3–0.9)。

结论

CPMD 在低收入和中低收入国家更加普遍,特别是存在性别风险或精神病史的更加贫穷的女性。

Резюме

Цель

Установить степень распространенности и детерминанты непсихотических общих перинатальных психических расстройств (ОППР) в странах с низким уровнем доходов и доходами ниже среднего уровня согласно классификации Всемирного банка.

Методы

Был проведен систематический поиск в основных базах данных публикаций на английском языке по теме распространенности непсихотических ОППР, их факторов риска и детерминант. Алгоритмы исследований прилагаются.

Результаты

13 документов, охватывающих 17 стран с доходами ниже среднего уровня, которые содержат результаты исследований беременных женщин, и 34 документа исследований недавно родивших женщин. Данные о нарушениях в дородовый период были доступны для 9 (8%) стран, а для нарушений в послеродовый период – для 17 (15%) стран. Взвешенное среднее значение распространенности составило 15,6% (95% доверительный интервал, ДИ: 15,4–15,9) в дородовой период и 19,8% (19,5–20,0) в послеродовой период. Факторами риска явились: социально-экономическое неблагополучие (отношение рисков [ОР]: 2,1–13,2); нежелательная беременность (1,6-8,8), женщина моложе партнера (2,1-5,4), женщина не замужем (3,4-5,8); недостаток интимного сопереживания и поддержки партнера (2,0-9,4); неприязнь ближайших родственников мужа (2,1-4,4); сексуальное насилие со стороны партнера (2,11-6,75); недостаточная эмоциональная и практическая поддержка (2,8-6,1), в некоторых ситуациях, рождение девочки (1,8-2,6), а также наличие предыдущих проблем с психическим здоровьем (5,1-5,6). Защитными факторами явились: более высокий уровень образования (относительный риск: 0,5; P = 0,03); наличие постоянной работы (ОР: 0,64; 95% ДИ: 0,4–1,0); принадлежность к этническому большинству (ОР: 0,2; 95% ДИ: 0,1–0,8) и наличие доброго и надежного интимного партнера (ОР: 0,52; 95% ДИ: 0,3–0,9).

Вывод

ОППР более распространены в странах с низким уровнем доходов и доходами ниже среднего уровня, особенно среди более бедных женщин с наличием гендерных рисков или психиатрического анамнеза.

Introduction

The nature, prevalence and determinants of mental health problems in women during pregnancy and in the year after giving birth have been thoroughly investigated in high-income countries.1 Systematic reviews have shown that in these settings, about 10% of pregnant women and 13% of those who have given birth2 experience some type of mental disorder, most commonly depression or anxiety.3 Social, psychological and biological etiological factors interact, but their relative importance is debated.

The perinatal mental health of women living in low- and lower-middle-income countries has only recently become the subject of research,1 in part because greater priority has been assigned to preventing pregnancy-related deaths. In addition, some have argued that in resource-constrained countries women are protected from experiencing perinatal mental problems through the influence of social and traditional cultural practices during pregnancy and in the postpartum period.4,5

This systematic review was performed with the objective of summarizing the evidence surrounding the nature, prevalence and determinants of non-psychotic common perinatal mental disorders (CPMDs) among women living in low- and lower-middle-income countries.

Methods

Search strategy

A senior librarian in the World Health Organization (WHO) headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland, conducted a systematic search of the literature to identify sources dealing with the prevalence of CPMDs and the factors that make women more vulnerable to, or that protect them from, these disorders. Several databases were searched for studies published up to November 2010 (Box 1). Reference lists of the papers meeting inclusion criteria were hand searched to identify further studies.

Box 1. Literature search strategya for systematic review of the evidence on the prevalence and determinants of common perinatal mental disorders.

1. “prenatal” OR “antenatal” OR “pregnancy” OR “postnatal” OR “postpartum”

2. “mental disorder” OR “adjustment disorder” OR “affective disorder” OR “dysthymic disorder” OR “psychiat*” OR “behaviour control” OR “psychological phenomena” OR “depression” OR “mental health” OR “stress disorder” OR “anxiety disorder” OR “maternal welfare” OR “maternal health”

Combined terms: 1 AND 2.

a Limited to World Bank defined low- and lower-middle-income countries.

Note: The following databases were searched for papers published up to November 2010: CINAHL, PsychInfo, Medline, RefMan and Web of Science.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The search was confined to studies published in English or with sufficiently detailed English abstracts to enable comparison of the methods and main findings. Only investigations of the nature, prevalence and determinants of non-psychotic CPMDs in women in low- and lower-middle-income countries, as defined by World Bank country income categories, were included. Data about these countries were obtained from published inter-country comparisons that included at least one low- or lower-middle-income country. Although China is classified as a lower-middle-income country, economic conditions and health infrastructure in Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (Hong Kong SAR) and in Taiwan are very different from those in mainland China and in the resource-constrained settings that are the focus of this review. We therefore included in the analysis studies from mainland China but not from Hong Kong SAR or Taiwan. From studies whose findings were stratified by maternal age, we extracted data only for adults, not adolescents (people aged up to 19 years). We included all studies from which outcome data on CPMDs could be extracted, regardless of study design. Information was extracted systematically using a standardized data extraction form.

Quality assessment

The methodological quality of each study was assessed by two authors independently using the Mirza and Jenkins checklist of eight items,6,7 with an additional item pertaining to whether appropriate informed consent to participate in the study had been obtained. Differences were discussed and consensus reached. The checklist included the following quality criteria: (i) explicit study aims; (ii) adequate sample size or justification; (iii) sample representative, with justification; (iv) clear inclusion and exclusion criteria; (v) measures of mental health reliable and valid, with justification; (vi) response rate reported and losses explained; (vii) adequate description of data; and (viii) appropriate statistical analyses. One point was given for a “yes” answer and none for a “no” answer, for a possible maximum score of 9 points (Table 1, available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/90/2/11-091850).

Table 1. Methodological quality of studies of common perinatal mental disorders among women living in low- and lower-middle-income countries, as per World Bank classification (1 = yes; 0 = no).

| Study | Clear study aims | Adequate sample size (or justification) | Representative sample (with justification) | Clear inclusion and exclusion criteria | Measure of mental health valid and reliable | Response rate reported and losses given | Adequate description of data | Appropriate statistical analysis | Appropriate informed consent procedure | Total score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abiodun et al., 19938 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Abiodun, 20069 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| Aderibigbe et al., 199310 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Adewuya, 200611 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Adewuya & Afolabi, 200512 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| Adewuya et al., 200513 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Adewuya et al., 200714 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Affonso et al., 200015 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Agoub et al., 200516 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Black et al., 200717 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Chandran et al., 200218 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Cox et al., 197919 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| Ebeigbe & Akhigbe, 200820 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Edwards et al., 200621 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Faisal-Cury et al., 200422 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Fisher et al., 200423 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Fisher et al., 200724 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Fisher et al., 201025 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Gao et al., 200926 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Gausia et al., 200927 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Gausia et al., 200928 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 8 |

| Gausia et al., 200729 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Hanlon et al., 200930 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Ho-Yen et al., 200731 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Husain et al., 200632 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Karmaliani et al., 200633 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Limlomwongse et al., 200634 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Montazeri et al., 200735 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Nagpal et al., 200836 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Nakku et al., 200637 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Nhiwatiwa et al., 199838 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Owoeye et al., 200639 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Patel et al., 200240 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Pitanupong et al., 200741 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Piyasil,199842 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| Pollock et al., 200943 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Regmi et al., 200244 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Rahman et al., 200345 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Stewart et al., 200846 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Uwakwe, 200347 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Wan et al., 200948 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Xie et al., 200749 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

Analysis

Varied endpoints were reported: scores above thresholds on symptom screening measures, diagnoses by mental health practitioners or structured clinical interviews by research workers, and a combination of these. Self-reported symptom measures, including the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), detect but do not distinguish between symptoms of anxiety and depression.50 Most studies that generated psychiatric diagnoses only assessed depression and not other disorders, such as anxiety. Therefore they yielded diverse data about the prevalence, severity and duration of non-specific and specific symptoms, including those that met the diagnostic criteria. We used Goldberg’s construct, Common Mental Disorders,51 for non-psychotic mental health conditions including depressive, anxiety, adjustment and somatic disorders which compromise day-to-day functioning and are identifiable in primary health care settings anywhere. Meta-analysis was undertaken to assess antenatal and postnatal prevalence, and heterogeneity was quantified with the I2 statistic. Aggregate means, weighted by participant numbers, were calculated for comparisons between studies from different health sectors. Publication bias was assessed with the Egger test and represented graphically by a funnel plot.

Results

The steps involved in identifying studies meeting the inclusion criteria are summarized in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Study selection process for systematic review of studies on common perinatal mental disorders in women in low- and lower-middle-income countries

HI, higher income; LALMI, low- and lower-middle-income countries.

We identified 13 studies that reported point prevalence data about common mental disorders in pregnant women (Table 2, available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/90/2/11-091850) and 34 that assessed women at some point in the year after giving birth (Table 3, available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/90/2/11-091850). There were 21 prospective studies with at least two assessment waves, but none reported incidence.

Table 2. Methods of investigating common perinatal mental disorders in pregnant women in low- and lower-middle-income countries, as per World Bank country income classification.

| Study | Study type | Setting | Quality | Sample | Gestational age | Assessment instrument | Prevalence (%) | SANCa (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tertiary hospitals | ||||||||

| Abiodun et al., 19938 | Cross-sectional survey Validation of GHQ-30 | University of Ilorin Teaching Hospital, Nigeria | 7 | 240/250 consecutive attendees at antenatal clinics fluent in English or Yoruba | Trimester 1 (20.8%) Trimester 2 (33.3%) Trimester 3 (45.95%) | GHQ 30b > 4 | 19.1 | 58 |

| PSE | 12.5 | |||||||

| Aderibigbe et al., 199310 | Prospective cohort Validation of GHQ-28 | University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria | 6 | 277/300 consecutive attendees at antenatal clinics | Trimester 2 | C-GHQ-28b > 7 | 27.1 | 58 |

| PAS | 14.4 CMD | |||||||

| Karmaliani et al., 200633 | Cross-sectional survey | Civil Hospital, Hyderabad, Pakistan | 8 | 1000 first recruited women 20–26 weeks pregnant and living locally, identified during routine household visits of 1368/1879 in larger study | Trimester 2 | AKUADSb > 31.5 | 11.5 | 64 |

| How I feel scale > 83.5 | 13.5 | |||||||

| Limlomwongse and Liabsuetrakul, 200634 | Prospective cohort | Antenatal clinics Songlanagarind University Hospital, Thailand | 8 | 612/833 women, consecutive attendees at antenatal clinics | Trimester 3 | EPDS > 10 | 20.5 | 98 |

| EPDS > 12 | 5.2 | |||||||

| Fisher, Tran & Tran, 200724 | Cross-sectional survey | National Obstetric Hospital, Hanoi, Viet Nam | 6 | Convenience sample of 61/74 women attending antenatal clinics | Trimester 3 | EPDS 10–12 | 13.1 | 91 |

| EPDS > 12 | 1.6 | |||||||

| Provincial or district health services | ||||||||

| Cox et al., 197919 | Cross-sectional | Antenatal clinics at semi-rural teaching health centres, Uganda | 6 | 263 antenatal clinic attendees | SISb | 16 CMD | 94 | |

| Nhiwatiwa et al., 199838 | Prospective cohort | Periurban primary care clinics, Zimbabwe | 5 | 500/500 consecutive attendees ≥ 32 weeks pregnant at antenatal and primary-health-care clinics | Trimester 3 | SSQb | 19.0 high risk | 94 |

| CIS-R | ||||||||

| Chandran et al., 200218 | Prospective cohort | Christian Medical College, Vellore community health service, India | 5 | 384/991 consecutive attendees at antenatal clinics intending to live locally after giving birth | Trimester 3 | CIS-Rb | 16.2 depression | 74 |

| Adewuya et al., 200714 | Cross-sectional survey Validation of EPDS | Semi-urban health centres in Ilesa, Nigeria | 5 | 180 consecutive attendees at antenatal clinics who were well and could speak English or Yoruba | Trimester 3 | EPDSb > 5 | 41.6 | 58 |

| MINI (DSM-IV) | 8.3 depression | |||||||

| Fisher et al., 201025 | Cross-sectional clinical and structured interviews | Randomly selected urban and rural commune health centres, Viet Nam | 8 | 65/70 women > 28 weeks pregnant registered with the CHC in Hanoi (urban) | Trimester 3 | SCIDb (DSM-IV) | 21.5 CMD | 91 |

| 134/148 > 28 weeks pregnant registered with the CHC in Hanam (rural) | SCIDb (DSM-IV) | 32.9 CMD | ||||||

| Community | ||||||||

| Rahman et al., 200345 | Prospective cohort | Kaller Syedan QH and Choha Khalsa QH, a rural low-income subdistrict, Pakistan | 8 | 632/701 women > 28 weeks pregnant in households visited by Lady Health Workers or identified by vaccinators or TBAs who did not have psychotic or chronic illness or intellectual disability | Trimester 3 | SCANb (ICD-10) | 25.0 depression | 64 |

| Gausia et al., 200927 | Prospective cohort | Demographic Surveillance Site, Matlab, Bangladesh | 6 | 361/410 women > 33 weeks pregnant registered with MCH programme | Trimester 3 | EPDS-Bb > 9 | 33.0 | 60 |

| Hanlon et al., 200930 | Prospective cohort | Demographic Surveillance Site Butajira Rural Health Program, Ethiopia | 8 | 1065/1234 women > 28 weeks pregnant, residing in DHSS and identified by Butajira Rural Health Program enumerators in household visits | Trimester 3 | SRQ-20b 1–5 “low symptoms” | 59.5 | 28 |

| SRQ-20b > 5 “high symptoms” | 12.0 |

AKUADS, Aga Khan University Anxiety Depression Scale; CHC, commune health centre; CIS-R Clinical Interview Schedule-Revised; C-GHQ, conventional scoring method; CMD, common mental disorder; DHSS, Demographic and Health Surveillance System; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edition; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; GHQ, General Health Questionnaire; ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases, tenth revision; MCH, Maternal and Child Health; MINI, Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview; PAS, Psychiatric Assessment Schedule; PSE, Present State Examination; QH, Qanungo Halqa (an administrative subdistrict); SANC, skilled antenatal care; SCAN, Schedule for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV; SIS, Standardised Interview Schedule; SRQ-20, World Health Organization Self Reporting Questionnaire; SSQ, Shona Symptom Questionnaire; TBA, traditional birth attendant.

a Proportion of pregnant women given skilled antenatal care.

b Instrument locally validated.

Table 3. Methods of investigating common perinatal mental disorders in women in resource-constrained countries who had recently given birth.

| Study | Study type | Setting | Qualitya | Sample | Postpartum assessment time | Assessment instrument(s) | Prevalence (%) | SBAb (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tertiary hospitals | ||||||||

| Aderibigbe et al., 199310 | Prospective cohort from pregnancy Validation of GHQ 28 | University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria | 4 | 277/300 women attending antenatal clinics | 6–8 wk | C-GHQ 28c > 7 | 14.0 | 39 |

| Piyasil, 199842 | Cross-sectional survey | Rajvithi Teaching Hospital, Thailand | 5 | Convenience sample of 94 women aged ≥ 21 years in the postnatal wards | During postnatal hospital stay | Questions to assess DSM-IV criteria for depression and anxiety | 11.9 “high depressive scores”; 12.0 “high anxiety scores” | 97 |

| Regmi et al., 200244 | Cross-sectional survey Validation of EPDS | Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital, Kathmandu, Nepal | 5 | Convenience sample of 100/100 women attending a postnatal clinic | 2–3 mo | EPDS > 12 Diagnostic interview for DSM-IV major depression | 12.0 | 19 |

| Uwakwe, 200347 | Cross sectional survey Validation of EPDS | Nnamdi Aziiwe Teaching Hospital Nigeria | 6 | 225/292 women in postnatal ward for ≥ 7 days, or attending postnatal clinics | 6–8 wk | ICD-10 SCLc | 10.7 depression | 39 |

| Faisal-Cury et al., 200422 | Cross-sectional survey | Sao Paulo University Medical School, Brazil (LALMIC 2004) | 6 | 113/172 uninsured women attending an obstetric clinic | 10 d | BDIc > 15 | 15.9 | 88 |

| Limlomwongse & Liabsuetrakul, 200634 | Prospective cohort from pregnancy | Songlanagarind University Hospital Thailand | 6 | 525/612 consecutive women attendees at antenatal clinics followed up at postnatal clinics | 6–8 wk | EPDSc > 10 | 16.8 | 97 |

| Xie et al., 200749 | Prospective cohort from early postpartum | Hunan Maternity Care Hospital; First, Second and Third Affiliated hospitals of Central South University, Hunan, China | 7 | 300/370 primiparous women without psychiatric histories and with singleton infants | 6 wk | EPDSc > 12 | 17.3 | 95 |

| Pitanupong et al., 200741 | Prospective cohort from pregnancy | University hospital, southern Thailand | 7 | 351/450 consecutive women attendees at antenatal clinic without psychiatric histories | 6–8 wk | EPDS > 6 | 11.0 | 97 |

| Ebeigbe and Akhigbe, 200820 | Cross-sectional survey | University of Benin Teaching Hospital, Benin City, Nigeria | 7 | 206/215 women attendees at postpartum clinic who could speak English | 6 wk | EPDSc > 9 | 27.2 | 39 |

| Wan et al., 200948 | Cross-sectional survey | Peking University First Hospital, Beijing, China | 7 | 365/395 women postpartum clinic attendees | 6–8 wk | EPDSc > 12 | 15.5 | 95 |

| Pollock et al., 200943 | Cross-sectional survey | Urban hospital(s) Ulaanbataar, Mongolia | 7 | 1044/1274 women with healthy babies in follow-up home visits | 5–9 wk | SRQc 20 > 8 | 9.1 | 100 |

| Tertiary hospital and community clinics | ||||||||

| Fisher et al., 200423 | Cross-sectional survey | Hung Vuong Hospital and MCH and family planning clinic, Ho Chi Minh City Viet Nam | 8 | 506/516 consecutive women attendees at six-week infant health clinic | 6 wk | EPDS > 12 | 32.9 | 88 |

| Adewuya et al., 200513 | Cross-sectional survey validation of the EPDS | Wesley Guild Hospital and Obafemi Awolowo Hospital health centres, Ilesa East and West MCH centres, Ilesa Nigeria | 7 | 876/928 women attendees at infant immunization clinics | 6–8 wk | EPDSc ≥ 9 + BDI + SCID-NP | 14.6 depression | 39 |

| Provincial or district hospitals | ||||||||

| Patel et al., 200240 | Prospective cohort study from pregnancy | Asilo Hospital, Mapusa, Goa, India | 7 | 252/270 women attending antenatal clinics 235/270 | 6–8 wk | EPDSc > 11 | 23.0 | 47 |

| 6 mo | EPDSc > 11 | 22.0 | ||||||

| Edwards et al., 200621 | Prospective cohort study from late pregnancy | Soetomo, Saint Paulo and Griya Husada Hospitals, Indonesia | 7 | 434/472 healthy married women, literate in Indonesian and without a psychiatric history | 4–6 wk | EPDS > 10 | 22.4 | 73 |

| Owoeye et al., 200639 | Prospective cohort study from 5 days postpartum | Postnatal wards at Lagos Island Maternity Hospital, Nigeria | 7 | 252/280 women “in maternity hospital” | 4–6 wk | EPDSc > 11, depression confirmed in most by clinical interview for ICD-10 criteria | 23.0 | 39 |

| Ho-Yen et al., 200731 | Cross-sectional survey | Patan Hospital, Lalitpur District health services, Nepal | 6 | 426/447 women with living babies | 5–10 wk | EPDSc > 12 | 4.9 | 19 |

| Gao et al., 200926 | Cross-sectional survey | Two regional hospitals in Guangzhou, China | 7 | Convenience sample of 130/139 married primiparous couples with healthy babies and no psychiatric history | 6 – 8 wk | EPDSc > 12 | 13.8 | 95 |

| Provincial or district health services | ||||||||

| Nhiwatiwa et al., 199838 | Prospective cohort from late pregnancy | Periurban primary care clinics Zimbabwe | 6 | 95 “high risk” women (pregnancy SSQ > 7) and 110 “low risk” women (SSQ ≤ 6) | 6–8 wk | Shona RCISc > 13 | 16.0, CMD | 69 |

| Affonso et al., 200015 | Prospective cohort studies in 9 countries: India and Guyana LALMIC | Community and health clinics accessible to “nurse researchers” | 7 | Convenience samples in each country | ||||

| India | 110 | 1–2 wk | EPDSc > 9 | 35.5 | 47 | |||

| 106 | BDIc > 12 | 32.7 | ||||||

| 102 | 4– 6 wk | EPDSc > 9 | 32.4 | |||||

| 101 | BDIc > 12 | 24.5 | ||||||

| Guyana | 106 | 1–2 wk | EPDSc > 9 | 50 | NA | |||

| 102 | BDIc > 12 | 29.8 | ||||||

| 93 | 4– 6 wk | EPDSc > 9 | 57 | |||||

| 97 | BDI > 12 | 24.6 | ||||||

| Adewuya & Afolabi, 200512 | Prospective cohort from early postpartum | 5 urban health centres, Ilesa, Nigeria | 5 | 632/674 healthy women who had spontaneous vaginal births and were literate in local languages, recruited consecutively | 1 wk | Zung SDSc | 48 CMD symptoms | 39 |

| Zung SASc | ||||||||

| 4 wk | 28.2 | |||||||

| 8 wk | 25.5 | |||||||

| 12 wk | 24.7 | |||||||

| 24 wk | 18.3 | |||||||

| 36 wk | 14.4 | |||||||

| Agoub et al., 200516 | Prospective cohort from early postpartum | Primary MCH unit, Casablanca, Morocco | 6 | 144/144 married women, recruited consecutively | 2 wk | MINIc (DSM-IV) | 18.7 | 63 |

| EPDSc > 12 | 20.1 | |||||||

| 6 wk | MINIc (DSM-IV) | 6.9 | ||||||

| 6 mo | MINIc (DSM-IV) | 11.8 | ||||||

| 9 mo | MINIc (DSM-IV) | 5.6 | ||||||

| Abiodun, 20069 | Cross-sectional survey Validation EPDS | 3 primary health-care clinics, Kwara Nigeria | 6 | 360/379 women literate in local languages, recruited consecutively | 6 wk | EPDS > 8 + PSE | 18.6 | 39 |

| Adewuya, 200611 | Prospective cohort from early postpartum | 5 urban health centres Ilesa Nigeria | 7 | 478/582 healthy women who had spontaneous vaginal births and were literate in local languages, recruited consecutively | 5 d | EPDSc > 9 | 20.9 | 39 |

| 4 wk | SADS | 10.7 depression | ||||||

| 8 wk | SADS | 16.3 depression | ||||||

| Nakku et al., 200637 | Cross-sectional survey | Periurban health centre, Kampala, Uganda | 7 | 544/544 women attending a postnatal clinic | 6 wk | SRQ 25c > 5 + MINIc for F scoring > 5, but F scoring < 5 | 6.1 depression | 42 |

| Gausia et al., 200729 | Cross-sectional survey Validation of the EPDS | Immunisation clinic Dhaka, Bangladesh | 4 | Convenience sample of 100/126 women | 6–8 wk | SCID (DSM-IV) | 9.0 depression | NA |

| Montazeri et al., 200735 | Cross-sectional survey Validation of EPDS | Urban health care centres, Isfahan, Islamic Republic of Iran | 6 | Consecutive samples of 50/50 women after vaginal and 50/50 after caesarean births | 6–8 wk | EPDS 10 – 12 | 15.0 | NA |

| EPDS > 12 | 22 | |||||||

| 12–14 wk | EPDS > 12 | 18.0 | ||||||

| Stewart et al., 200846 | Cross-sectional survey | Child health clinic, Thyolo District Hospital, Malawi | 7 | 501/519 women attending the clinic with their infants and recruited consecutively | 9–10 mo | SRQ > 7 | 29.9 | 57 |

| Gausia et al., 200928 | Prospective cohort from late pregnancy | Primary MCH clinics Matlab DSS, Bangladesh | 4 | 346/410 women identified from computer records as pregnant and assessed at postpartum follow-up | 6–8 wk | EPDSc > 9 | 22 | NA |

| Fisher et al., 201025 | Cross-sectional | Randomly selected urban and rural commune health centres in northern Viet Nam | 8 | 65/70 women who had given birth in Ha Noi | 6 – 8 wk | SCID | 26.1, CMD | 88 |

| 100/107 eligible women who had given birth in Hanoi | SCID | 34, CMD | ||||||

| Community | ||||||||

| Rahman et al., 200345 | Prospective cohort from late pregnancy | Households visited by Lady Health Workers in Tehsil Kahuta, a rural low-income subdistrict, Pakistan | 7 | 541/632 women recruited consecutively | 10–12 wk | SCAN | 28 depression | 39 |

| Husain et al., 200632 | Cross-sectional survey | Households visited by Lady Health Workers in Kaller Syedan, a subdistrict of Rawalpindi, Pakistan | 7 | 149/175 women recruited consecutively | 12 wk | EPDS > 11 | 36.0 | 39 |

| Black et al., 200717 | Cross-sectional survey | DSS identified participants in Matlab, rural Bangladesh | 8 | 221/346 DSS identified eligible women | 12 mo | CES-D > 16 | 52.0 | NA |

| Nagpal et al., 200836 | Cross-sectional survey Validation of the Mother Generated Index | House to house recruitment in randomly selected colonies, New Delhi, India | 6 | 195/249 women identified as eligible by surveyors | Up to 6 mo | EPDS > 9 | 59.4 | 47 |

BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies – Depression Scale; C-GHQ, conventional scoring method; CIS-R, Revised Clinical Interview Schedule; CMD, common mental disorder; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edition; DSS, Demographic Surveillance System; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; GHQ, General Health Questionnaire; ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases, tenth revision; LALMIC, low- and lower-middle-income country; MBS, Maternity Blues Scale; MCH, Maternal and Child Health; MINI, Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; NA, not available; PSE, Present State Examination; SADS, Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia; SBA, skilled birth attendant; SCAN, Schedule for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview; SCID-NP, Structured Clinical Interview - Non-patient Edition; SCL, ICD-10 Symptom Checklist for Mental Disorders; SDS, Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale; Shona R-CIS, SRQ, Self-Reporting Questionnaire; SSQ, Shona Symptom Questionnaire, TBA, traditional birth attendant..

a Two studies included structured interviews using DSM-III or DSM-IV criteria.10,46

b Proportion of births with a skilled birth attendant.

c Instrument locally validated.

Prevalence

Pregnancy

Data on the antenatal prevalence of common mental disorders were available from only 8% (9/112) of low- and lower-middle-income countries. Most of the articles containing such data (9/13, 69%) were published after 2002. Patel et al.,40 Husain et al.32 and Liabsuetrakul et al.52 generated evidence about risks, including the risk of antenatal depression for postnatal depression, and Fatoye et al.53 compared symptoms in pregnant and non-pregnant women. None of these studies reported on the prevalence of common mental disorders during pregnancy.

In almost all studies (11/13, 85%), participants were recruited while attending a health facility for antenatal care. In general, recruitment strategies were not described in detail and few studies considered potential selection biases. Where antenatal care coverage is high, consecutive cohorts yield reasonably representative samples of pregnant women. However, in many low- and lower-middle-income countries high proportions of women lack access to antenatal care or make fewer than the recommended visits. Overall, 5 of the 13 studies (39%) recruited women from urban tertiary teaching hospitals, which are inaccessible to the majority who live in rural areas and to those who cannot pay for antenatal care. These studies thus over-represent relatively advantaged women. Most other studies (5/13, 39%) recruited women from community-based health services, which are more accessible to the general population but will not yield representative samples in settings where few women receive antenatal care. Three studies generated population-based samples in low- and lower-middle-income countries with low antenatal care coverage. In Pakistan, Rahman et al.45 recruited women via household visits by female community health workers and thereby included pregnant women unlikely to attend antenatal services. Gausia et al.27 in Bangladesh and Hanlon et al.30 in Ethiopia used sites covered by Demographic Surveillance Systems to identify eligible pregnant women who were then assessed during household visits by a health worker or surveillance site enumerator.

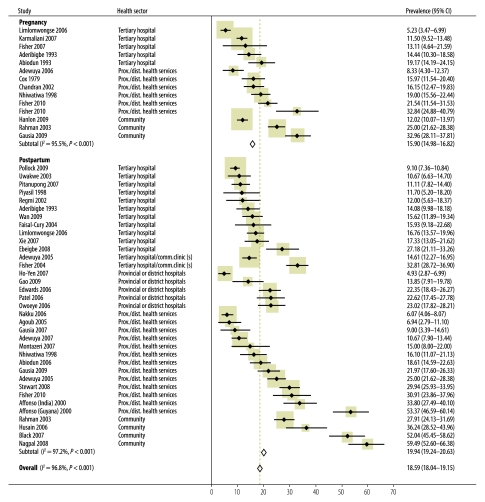

The least representative samples are therefore likely to be those from tertiary hospitals in low- and lower-middle-income countries where most women live in rural areas and few (< 65%) attend antenatal care (two studies from Nigeria8,10 and one from Pakistan33). The most representative ones, on the other hand, are those that recruited systematically in health services, including those located in rural areas, in low- and lower-middle-income countries where most women (> 90%) make at least one antenatal visit,25,38 or those that recruited women who would not usually attend antenatal care, systematically27,30,45 (Fig. 2 and Table 4).

Fig. 2.

Meta-analysis of individual study and overall prevalence of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low- and lower-middle-income countries

CI, confidence interval.

Table 4. Overall and health-sector-specific weighted mean prevalence of common perinatal mental disorders (CPMDs) in different facilities in low-and lower-middle-income countries.

| Facility type | Total sample (No. of studies) | Prevalence range (%) | Weighted mean prevalence (%) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPMD during pregnancy | ||||

| All studies | 5 774 (13) | 5.2–32.9 | 15.6 | 15.4–15.9 |

| Tertiary hospitals | 2 190 (5) | 5.2–14.4 | 10.3 | 10.1–10.4 |

| Provincial or district health services | 1 526 (5) | 8.3–32.9 | 17.8 | 17.4–18.3 |

| Community | 2 058 (3) | 12.0–33.0 | 19.7 | 19.2–20.1 |

| CPMD after childbirth | ||||

| All studies | 11 581 (34) | 4.9–59.4 | 19.8 | 19.5–20.0 |

| Tertiary hospitals | 3 600 (11) | 9.1–27.2 | 13.6 | 13.5–13.8 |

| Tertiary hospitals and community clinics | 2 876 (7) | 4.9–32.9 | 18.9 | 18.7–19.3 |

| Provincial or district health services | 3 999 (12) | 6.1–35.5 | 20.4 | 20.1–20.8 |

| Community | 1 106 (4) | 28.0–59.4 | 39.4 | 38.6–40.3 |

CI, confidence interval.

Average prevalence (15.9%: 95% confidence interval, CI: 15.0–16.8%) was higher than in high-income countries. Meta-analysis revealed significant differences between prevalence estimates based on self-reported symptom measures (13.43%; 95% CI: 12.4–14.5) and prevalence estimates based on diagnostic assessment (21.75 %; 95% CI: 19.8–23.7). However, all studies based on diagnostic assessments but only 55% of those in which self-report measures were used took place in provincial or community settings, where prevalence appears to be higher (Table 4).

Postpartum

Evidence about the prevalence of common mental disorders postpartum was available for 15% (17/112) of low- and lower-middle-income countries; most (30/34, 88%) of the studies were published after 2002. The papers reported 14 cohort and 20 cross-sectional studies, most of which were at least of reasonable quality. Overall the methods were more rigorous in the recent studies than in the older ones. The most common limitations were failure to specify inclusion criteria or to describe recruitment strategies. All studies addressed limited literacy by using questionnaires administered by an interviewer in the local language. All but one34 of these questionnaires had been appropriately validated.

Among studies with clearly-described selection criteria, many excluded participants with characteristics relevant to the outcomes. For example, some studies excluded women who were illiterate34 or unable to speak the researchers’ language11,12,14,20,40,41,46,52–54 or who had a personal or family history of psychiatric problems.15,21,22,26,41,49,52,55 Such studies may have underestimated prevalence.

Almost one third (10/34, 29%) of the studies recruited participants from tertiary teaching hospitals. This occurred, for example, in Nigeria10,20,47 and Nepal,44 where less than 40% of the women receive skilled birth attendance and even fewer give birth in a hospital (Table 3). Thus, the findings from these studies cannot be generalized to the entire population of women who have recently given birth. The most representative samples are those recruited through rural health services in countries where more than 80% of women give birth with a skilled birth attendant,23,25,26,48,49 or through household visits in settings where women commonly give birth at home,.32,36,45 Samples obtained differently may have yielded inaccurate prevalence estimates (Fig. 2 and Table 4).

In our study countries, pooled prevalence of postpartum common mental disorders (19.8%; 95% CI: 19.2–20.6) was higher than in high-income countries. Meta-analyses revealed significant differences in mean prevalence estimates derived from self-reported symptom measures (20.80%; 95% CI: 20.0–21.6) and from diagnostic assessments (16.09%; 95% CI: 14.6–17.6). In the studies of postpartum symptoms about 50% of studies based on self-reported symptoms or on diagnostic assessment took place in provincial or district settings.

Overall meta-analyses revealed no differences in the pooled mean estimated prevalence of CPMDs derived from self-reported symptom measures (18.59%; 95% CI: 17.9–19.2) and diagnostic assessments (18.63%; 95% CI: 17.4–19.8).

Socioeconomic and intermediary determinants

Most studies (31/41, 76%) investigated risk and protective factors, while the remainder11,12,29,33,35,41,42,44,54,56 only reported prevalence data. Potential risk factors for CPMDs in women in low- and middle-income countries reflected diverse conceptual frameworks and differed between studies. This precluded data pooling. We used the framework of the WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health (Table 5).58

Table 5. Determinants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low- and lower-middle-income countries.

| Risk factors | OR rangea |

|

|---|---|---|

| Minimum OR (95% CI) | Maximum OR (95% CI) | |

| Social and economic circumstances | ||

| Socioeconomic disadvantage10,16,18,25,30,37,39,40,45,49 including: | 2.1 (95% CI: 1.3–5.2)37 | 13.2 (95% CI: 5.2–33.5)30 |

| – insufficient food or inability to pay for essential health care14,17,24,25,54,57 | ||

| – low income or financial difficulties10,21,57 | ||

| – an unemployed partner16 | ||

| – living in crowded or inadequate housing21or a rural area54 | ||

| Young age9,37,49 | 2.1 (95% CI: 0.7–6.4)49 | 5.4 (95% CI: 2.6–10.3)9 |

| Belonging to an ethnic or religious minority22,34 | 2.1 (95% CI: 1.0–4.0)]34 | |

| Being unmarried13,39,55 | 3.4 (95% CI: 2.2–5.5)13 | 5.8 (95% CI: 2.0–16.9)39 |

| Quality of relationship with intimate partner | ||

| Difficulties in intimate partner relationship8,24,25,27,28,30–32,38–40,45,48,53including: | 1.96 (95% CI: 1.0–3.9)48 | 9.44 (95% CI: 2.4–37.8)39 |

| – a partner who rejected paternity, was unsupportive, uninvolved, critical and quarrelsome or used alcohol to excess8,27,28,31,38,39,45,48 | ||

| – physical violence24,25,28,30–32,40 | 2.11 (95% CI: 1.1–4.0)25 | 6.75, (95% CI: 2.1–2.0)28 |

| – polygamous marriage31,53 | 7.7; 95% CI: 2.3–25.931 | |

| Family and social relationships | ||

| No help from, feared or argued with in-laws9,18,25,28,45,48 | 2.14 (95% CI: 1.1–4.3)48 | 4.4 (95% CI: 1.8–10.8)45 |

| Insufficient social support14,18 | 2.8 (95% CI: 1.2 – 6.4)18 | 6.1 (95% CI: 1.4 – 26.0)14 |

| – living in a nuclear family45 | 2.10 (95% CI: 1.2–3.8)25 | 4.3 (95% CI: 1.4–13.3)45 |

| – own mothers lived in a rural area38 | ||

| – lacked an affectionate and trusting relationship with their own mothers25 | ||

| Having at least three children22,38,45 | 2.6 (95% CI: 1.1–6.3)38 | 4.1 (95% CI: 0.9–19.0)22 |

| Reproductive and general health | ||

| Adverse reproductive outcomes8,9,11,13,23,30,37–40,49,53including: | ||

| Unwanted or unintended pregnancy23,30,37,39,40 | 1.6 (95% CI: 1.3–1.9)30 | 8.8 (95% CI: 4.5–17.5)39 |

| Nulliparity (in pregnant women) or primiparity (in women who had recently given birth)8,9,39 | 2.73 (95% CI: 1.4–4.2)9 | 4.16 (95% CI: 2.3 – 7.7)39 |

| Past spontaneous or induced abortion9,49,53 | 2.87 (95% CI: 1.0–8.0)49 | |

| Past stillbirth11,30 | 3.4 (95% CI: 1.3–8.7)30 | 8.0 (95% CI: 1.7–37.6)11 |

| Coincidental medical problems30,37,38 | 3.43 (95% CI: 1.8–6.6)37 | 8.3 (95% CI: 4.7–14.5)14 |

| Antenatal hospital admission13,57 | 3.21 (95% CI: 1.8–5.4)57 | 3.95 (95% CI: 2.6–6.1)13 |

| Caesarean birth13,39,55 | 2.49 (95% CI: 1.2–5.3)39 | 3.58 (95% CI: 1.7–7.5)13 |

| History of mental health problems | ||

| Past mental illness22,28,30,31,34,40 | 5.1 (95% CI: 1.7–15.2)31 | 5.6 (95% CI: 1.1–27.3)28 |

| Psychiatric morbidity in the index pregnancy11,28 | 3.2 (95% CI: 1.4–6.1)11 | 6.0 (95% CI: 3.0–12.0)28 |

| Non-specific psychological symptoms including: | 2.2 (95% CI: 1.4– 3.6)34 | 19.9 (95% CI: 3.3–122.0)22 |

| – past premenstrual irritability34 | ||

| – a “distancing coping pattern"22 | ||

| – anxiety about birth30 | ||

| – perceived pregnancy complications34 | ||

| – “negative pregnancy attitudes”34 | ||

| Infant characteristics | ||

| Not having a child of the desired sex18,26,37,45 | 1.8 (95% CI: 1.4–2.3)45 | 2.6 (95% CI: 1.2–6.5)18 |

| Infant cries for prolonged periods23 | 1.9 (95% CI: 1.2–3.0)23 | |

| Infant is ill16,37,40,48 | 1.1 (95% CI: 0.6–2.3)48 | 4.5 (95% CI: 3.2–6.4)40 |

| Grief associated with the death of an infant28,40 | 4.5 (95% CI: 3.6–5.8)40 | 14.1 (95% CI: 2.5–78.0)28 |

| Protective factors | ||

| More years of education40 | Relative risk: 0.5 (P = 0.03)40 | |

| Having a permanent or secure job23 | 0.64 (95% CI: 0.4–1.0)23 | |

| Having an employed partner40 | 0.3 (P = 0.002)40 | |

| Being a member of the ethnic majority22 | 0.2 (95% CI: 0.1–0.8)22 | |

| Traditional postpartum care from a trusted person23,45 | 0.4 (95% CI: 0.3–0.6)45 | 1.9 (95% CI: 1.1–3.2)23 |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

a Only one OR is provided if the data come from a single study.

Add footnote about RR

Socioeconomic factors

Nineteen studies9,10,13,16,18,20,22,25,30–32,34,36,37,39,40,47–49 investigated a variety of social, cultural and economic risk factors for CPMDs. Socioeconomic disadvantage was widely associated with increased risk10,16,18,25,30,37,39,40,45,49. Relative rather than absolute disadvantage also appears to be relevant: Wan et al.48 found that not owning a car in Beijing was associated with a higher risk of suffering a CPMD (odds ratio, OR: 1.9; 95% CI: 1.0–3.6). Rates of CPMD were also higher among women who were young9,37,49; of a religious minority,34 or unmarried.13,39,55 However, other studies found no association between CPMD and maternal age10,13,16,20,22,32,36,45,48; marital status9,34,37,47; economic difficulties or a low income13,22,26,32,36,45,48; unemployment9,16,26,34,36,47 or adverse life events.10,31

Quality of relationship with intimate partner

When other factors were controlled for, higher rates of CPMD were observed among women who experienced difficulties in the intimate partner relationship. Such difficulties included having a partner who rejected paternity, who was unsupportive and uninvolved, or critical and quarrelsome, and who used alcohol to excess.8,27,28,31,38,39,45,48 Higher average symptom scores among women in polygamous rather than monogamous marriages were found in Nigeria53 and Nepal,31 but not in Ethiopia.30

Only seven24,25,28,30–32,40 studies investigated an association with intimate partner violence. However, in 6 of them women who had experienced physical abuse during pregnancy or in the previous year had a higher prevalence of CPMDs than women who had not experienced these problems. In Viet Nam, pregnant women who felt “criticized over small things” (P < 0.01) and “controlled by their partners” (P < 0.03) had higher mean EPDS scores than others.24 Patel et al.40 found that the risk of chronic depression associated with intimate partner violence was higher if the baby was a girl (relative risk, RR: 1.9; 95% CI: 1.2–2.8) rather than a boy (RR: 1.7; 95% CI: 0.8–3.5). A few studies found no association between CPMD and “marital conflict",10,18,48 an “unhappy relationship with husband”32,37 or the “husband’s alcoholism".18

Family and social relationships

Eleven studies9,10,14,18,25–28,38,45,48 investigated the risks associated with difficult interpersonal relationships other than with the spouse. They focused in particular on conflicts between a woman and her in-laws in settings where women move into the in-laws’ household after marriage.9,18,25,28,45,48 The risk of CPMD was higher among women whose postpartum care was provided by their mothers-in-law or who received no help from their mothers-in-law at all, or among those who feared or argued with their in-laws or who had insufficient social support.17,24,26,42 In some studies, women who lived in a nuclear, rather than a multigenerational household,45 whose mothers lived in a rural area,38 or who lacked an affectionate and trusting relationship with their own mothers25 were at increased risk.45 However, no significant relationship of this kind was found in other studies.26,27

There was also mixed evidence regarding the relationship between CPMD and the number of living children in a woman’s care. While three studies22,38,45 found higher prevalence of CPMDs among women who had three or more children other studies found no association between family size and mental health.18,31,32

Reproductive and general health

Reproductive health and general health as risk factors for CPMDs were widely investigated.8,9,11,13,23,30,37–40,49,53 A higher risk was associated with adverse reproductive events including unwanted or unintended pregnancy, past pregnancy losses, coincidental illness and operative birth. However, other studies found no significant association between CPMDs and unwanted pregnancy,16,28 gravidity,22,36,48 parity13,16,20,22,34,37,47,57 prior stillbirth,18,20,34,39 coincidental medical problems48 or caesarean birth.16,20,23,26,36,40,55,57

History of mental health problems

Five studies22,28,30,34,40 identified risks associated with past mental health problems, including during pregnancy.11,28 These included past psychiatric illness and less specific psychological symptoms, which were found to increase risk. However, other studies found no association between CPMDs and a history of mental illness37 or with depression during the current pregnancy.31 In many settings that lack comprehensive mental health care, few women with common mental disorders are diagnosed or treated. In such settings it may not be possible to know whether a woman has a psychiatric history.

Infant characteristics

In many low- and lower-middle-income countries there is a cultural preference for male children. The potential association between this attitude and the risk of developing a CPMD was examined in various ways.10,16,17,22,26,28,32,39,48 In some studies such risk was increased among women who wanted a son but gave birth to a daughter37; who did not give birth to a child of the desired sex18; whose parents-in-law preferred a male baby,26 or who already had at least two daughters.45 However, other studies found no significant relationship between CPMD and the birth of a girl or with not having a child of the desired sex.10,16,17,22,26,28,32,39,48 The studies that investigated this risk yielded inconsistent evidence from China,37 Nigeria,10,13,39,57 and Pakistan45 but more consistent evidence of an increased risk from India18,40 and Uganda37 and of no risk from Bangladesh17,28 and Morocco.16

A few studies investigated whether an infant’s poor health and development was a risk factor for developing a CPMD. As most of these studies were cross-sectional, the direction of the relationship cannot be ascertained. Mothers may feel distressed because their infants are sick or failing to thrive. It is also possible, however, that mothers who have a CPMD are less able to provide sensitive care and that their babies are therefore vulnerable to health problems. Risk was increased among mothers who had experienced difficulty breastfeeding40 and those whose infants cried for prolonged periods.23 The prevalence of CPMDs was higher among mothers whose infants were ill than among those whose infants were well16,37,40,48 Grief following with the death of an infant was also detected in these surveys and associated with a higher risk of having a common mental disorder in the postpartum period28,40

Protective factors

Even among the poor, relative social and economic advantage appears protective.25 The risk of CPMDs was lower among women with more education40 a permanent or secure job,23 and an employed partner40 and among those belonging to the ethnic majority22

Two studies examined the relationship between the observation of traditional postpartum rituals and the risk of developing a CPMD. Rahman et al.45 in Pakistan found that the chilla ritual, which involves seclusion and the provision of heightened care to mothers and neonates in the first 40 days postpartum, was protective. Fisher et al.23 in Viet Nam found that culturally prescribed practices, such as lying over a charcoal fire or using cotton ear swabs to protect against the cold, were not related to the risk of CPMDs. However, practices that involved direct interpersonal care were relevant. Women who were given less than 30 days of rest were at increased risk (OR: 1.9; 95% CI: 1.1–3.2), but having someone to prepare special foods was protective (OR: 0.61; 95% CI: 0.4–1.0).

The quality of a woman’s intimate relationship with her partner can also act protectively. In Viet Nam women who scored > 33 on the Intimate Bonds Measure Care subscale, which assesses partner kindness, trust, sensitivity and affection, were at reduced risk25

Of the eight prospective studies initiated in pregnancy,10,21,27,34,38,40,41,45 five reported both the antenatal and postnatal prevalence of CPMDs and in four this was higher in pregnancy than after childbirth.

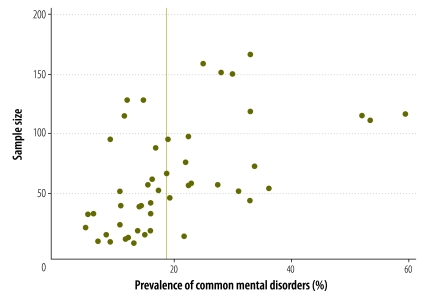

Test for publication bias

The funnel plots (Fig. 3) were skewed and asymmetrical. Normal statistical testing confirmed the presence of publication bias (total studies: Egger test P < 0.001; pregnancy studies: Egger test P = 0.013; postpartum studies: Egger test P < 0.001).

Fig. 3.

Funnel plot of studies on the prevalence of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low- and lower-middle-income countries

Discussion

There have been recent systematic reviews of studies dealing with perinatal mental disorders in women worldwide59 and in specific regions, including Asia6 and Africa,7 but to our knowledge this is the first review of studies about women in low- and lower-middle-income countries.

This review reveals a serious double disparity. One has to do with the availability of local evidence on which to base practice and policy. Tens of thousands of papers from high-income countries provide high-quality epidemiological, clinical, health service and health system evidence surrounding CPMDs. This stands in sharp contrast to the lack of local evidence about CPMDs in women in more than 80% of the world’s 112 low- and lower-middle-income countries and in 90% of the least-developed countries. Furthermore, few countries have more than one study in the English-language literature.

The settings, recruitment strategies, inclusion and exclusion criteria, representative adequacy of the samples and assessment measures used in the studies varied widely. Since all of these factors could have influenced prevalence estimates, only broad comparisons between low- and lower-middle-income countries and high-income countries can be made. We acknowledge this limitation. Nevertheless, the second disparity lies in the fact that in all the low- and lower-middle-income countries that report data, pregnant women and women who have recently given birth experience non-psychotic mental health conditions at substantially higher rates than the 10% in pregnancy2 and 13% postnatally3 reported in high-income countries.

These differences in the prevalence of CPMDs may result from the biased publication of studies reporting high rather than low prevalence in low- and lower-middle-income countries. However, we are all active researchers in this field and are not aware of unpublished studies that have reached different conclusions. It is also possible that the differences in prevalence merely result from the use of different study methods. While more recent studies have shown improvements over previous ones in the use of systematic sampling and locally validated assessment instruments, overall the studies were of reasonably high methodological quality and therefore this explanation is unlikely. It is possible, in fact, that the population prevalence of CPMDs in low- and lower-middle-income countries has been underestimated because the study sites and exclusion criteria may have resulted in the samples being disproportionately composed of women of relatively higher socioeconomic status and in better health, among whom prevalence is generally lower. Prevalence estimates are usually higher when based on self-reported symptom measures rather than on diagnostic assessment. This pattern was not consistent and overall prevalence estimates did not differ by method of assessment. Mental health problems may have been underestimated because most studies that used diagnostic interviews, considered the gold-standard, investigated depression but not other relevant psychological conditions, including perinatal anxiety disorders. Overall, we believe that the prevalence estimates are reliable. In low- and lower-middle-income countries about one in six pregnant women and one in five women who have recently given birth are experiencing a CPMD. This counters the notion that women’s mental health is protected by culturally-prescribed traditional postpartum care and suggests that it is erroneous to assume that this care is always available or welcome.

A few early studies in low- and lower-middle-income countries, most of which recruited women from tertiary hospitals, concluded that the prevalence of CPMDs was similar to that observed in high-income countries and that these conditions must therefore be biological in origin.12,19 Differences in the risk factors and protective factors found in the various studies reflect the use of different data sources (i.e. survey instruments containing either one or several study-specific questions) and standardized measures. Risks are likely to vary by cultural context and few studies assessed all the risk and protective factor domains that were identified. However, these data indicate that in these study settings, women’s mental health is governed significantly by social factors, including many beyond individual control.

Our review, which supports the conclusions reached by the Commission on the Social Determinants of Health,58 indicates that the prevalence of CPMDs is highest among the most socially and economically disadvantaged women, especially those living in crowded households in rural areas. Risk is also increased by gender-based factors, including the bias against female babies; role restrictions regarding housework and infant care, and excessive unpaid workloads, especially in multi-generational households in which a daughter-in-law has little autonomy. Gender-based violence, including both emotional and physical abuse, has adverse effects on women’s mental health and is especially destructive in the perinatal period, when a woman is more dependent. Such violence was consistently found to increase the risk of CPMD. As in high-income countries, the quality of a woman’s intimate partner relationship was found to be closely related to her perinatal mental health. Women whose partners welcomed the pregnancy and provided support and encouragement had better mental and emotional health.

The risk of CPMDs was lower among women with access to a better education, paid work, sexual and reproductive health services, including family planning, and supportive, non-judgmental family relationships. Overall the data indicate that CPMDs in women living in low- and lower-middle-income countries are caused by multiple factors and lack a direct causal pathway. Edwards et al.21 demonstrated that symptoms were more severe among women who had a greater number of risk factors and Patel et al.40 found that risk factors interact, including in culturally determined ways.

Mental health problems have serious consequences for women, their infants and their families. Although these problems are difficult to investigate because vital registration systems are often weak, suicide appears to contribute to maternal deaths in resource-constrained countries.60 Women with mental health problems are often stigmatized and are less likely to participate in antenatal, perinatal, postnatal and essential preventive health care.25 Infants are dependent on their mothers for breastfeeding, physical care, comfort and social interaction. Infant development is compromised if a mother is insensitive or unresponsive to the infant’s behavioural cues and needs. In low- and lower-middle-income countries, maternal depression is associated with higher rates of malnutrition and stunting, diarrhoeal diseases, infectious illnesses, hospital admissions, lower birth weight and reduced completion of immunization schedules among infants.46

While some women overcome their poor mental health over time, many have chronic mental health problems.40,45 In an international call to action on the part of WHO that was published in The Lancet in “No health without mental health", the point was made that addressing the major burden of mental health problems in resource-constrained countries is essential for development.61 Furthermore, Millennium Development Goals 4 and 5, which relate to the health of mothers and children, cannot be attained without due attention to maternal mental health.62 High-quality evidence about mental health problems in the perinatal period must be generated, especially at the local level, to make pregnancy safer for women in low- and lower-middle-income countries.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Women’s and Children’s Health Knowledge Hub funded by the Australian Agency for International Development. Daria Bodzak and Turi Berg provided expert research assistance for which the authors are most grateful. We are also grateful to Tomas Allen of the World Health Organization Geneva Library for undertaking the literature search and for the contribution to this work of the Victorian Operational Infrastructure Support Program.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.World development indicators [database]. Washington: World Bank; 2005. Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators [accessed 31 October 2011].

- 2.Hendrick V. Evaluation of mental health and depression during pregnancy. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1998;34:297–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Hara MW, Swain AM. Rates and risks of postpartum depression - a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry. 1996;8:37–54. doi: 10.3109/09540269609037816. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stern G, Kruckman L. Multi-disciplinary perspectives on post-partum depression: an anthropological critique. Soc Sci Med. 1983;17:1027–41. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(83)90408-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howard R. Transcultural issues in puerperal mental illness. Int Rev Psychiatry. 1993;5:253–60. doi: 10.3109/09540269309028315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mirza I, Jenkins R. Risk factors, prevalence, and treatment of anxiety and depressive disorders in Pakistan: systematic review. BMJ. 2004;328:794–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7443.794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sawyer A, Ayers S, Smith H. Pre- and postnatal psychological wellbeing in Africa: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2010;123:17–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abiodun OA, Adetoro OO, Ogunbode OO. Psychiatric morbidity in a pregnant population in Nigeria. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1993;15:125–8. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(93)90109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abiodun OA. Postnatal depression in primary care populations in Nigeria. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:133–6. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aderibigbe YA, Gureje O, Omigbodun O. Postnatal emotional disorders in Nigerian women: a study of antecedents and associations. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;163:645–50. doi: 10.1192/bjp.163.5.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adewuya AO. Early postpartum mood as a risk factor for postnatal depression in Nigerian Women. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1435–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.8.1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adewuya AO, Afolabi OT. The course of anxiety and depressive symptoms in Nigerian postpartum women. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2005;8:257–9. doi: 10.1007/s00737-005-0089-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adewuya AO, Fatoye FO, Ola BA, Ijaodola OR, Ibigbami SM. Sociodemographic and obstetric risk factors for postpartum depressive symptoms in Nigerian women. J Psychiatr Pract. 2005;11:353–8. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200509000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adewuya AO, Ola BA, Aloba OO, Dada AO, Fasoto OO. Prevalence and correlates of depression in late pregnancy among Nigerian women. Depress Anxiety. 2007;24:15–21. doi: 10.1002/da.20221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Affonso DD, De AK, Horowitz JA, Mayberry LJ. An international study exploring levels of postpartum depressive symptomatology. J Psychosom Res. 2000;49:207–16. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(00)00176-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agoub M, Moussaoui D, Battas O. Prevalence of postpartum depression in a Moroccan sample. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2005;8:37–43. doi: 10.1007/s00737-005-0069-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Black MM, Baqu AH, Zaman K, McNary SW, Le K, El Arifeen S, et al. Depressive symptoms among rural Bangladeshi mothers: implications for infant development. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48:764–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chandran M, Tharyan P, Muliyil J, Abraham S. Post-partum depression in a cohort of women from a rural area of Tamil Nadu, India: incidence and risk factors. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181:499–504. doi: 10.1192/bjp.181.6.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cox JL. Psychiatric morbidity and pregnancy: a controlled study of 263 semi-rural Ugandan women. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:401–5. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ebeigbe PN, Akhigbe KO. Incidence and associated risk factors of postpartum depression in a tertiary hospital in Nigeria. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2008;15:15–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edwards G, Shinfuku N, Gittelman M, Ghozali EW, Haniman F, Wibisono S, et al. Postnatal depression in Surabaya, Indonesia. Int J Ment Health. 2006;35:62–74. doi: 10.2753/IMH0020-7411350105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Faisal-Cury A, Tedesco JJA, Kahhale S, Menezes PR, Zugaib M. Postpartum depression: in relation to life events and patterns of coping. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2004;7:123–31. doi: 10.1007/s00737-003-0038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fisher JRW, Morrow MM, Nhu Ngoc NT, Hoang Anhc LT. Prevalence, nature, severity and correlates of postpartum depressive symptoms in Vietnam. BJOG. 2004;111:1353–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fisher JR, Tran H, Tran T. Relative socioeconomic advantage and mood during advanced pregnancy in women in Vietnam. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2007;1:3. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fisher J, Tran T, Buoi LT, Kriitmaa K, Rosenthal D, Tuan T. Perinatal mental disorders and health care use in Viet Nam. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:737–45. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.067066. [doi:] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao LL, Chan SW, Mao Q. Depression, perceived stress, and social support among first-time Chinese mothers and fathers in the postpartum period. Res Nurs Health. 2009;32:50–8. doi: 10.1002/nur.20306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gausia K, Fisher C, Ali M, Oosthuizen J. Antenatal depression and suicidal ideation among rural Bangladeshi women: a community-based study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s00737-009-0080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gausia K, Fisher C, Ali M, Oosthuizen J. Magnitude and contributory factors of postnatal depression: a community-based cohort study from a rural subdistrict of Bangladesh. Psychol Med. 2009;39:999–1007. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708004455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gausia K, Fisher CM, Algin S, Oosthuizen J. Validation of the Bangla version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale for a Bangladeshi sample. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2007;25:308–15. doi: 10.1080/02646830701644896. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanlon C, Medhin G, Alem A, Tesfaye F, Lakew Z, Worku B, et al. Impact of antenatal common mental disorders upon perinatal outcomes in Ethiopia: the P-MaMiE population-based cohort study. Trop Med Int Health. 2009;14:156–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ho-Yen SD, Tschudi Bondevik GT, Eberhard-Gran M, Bjorvatn B. Factors associated with depressive symptoms among postnatal women in Nepal. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86:291–7. doi: 10.1080/00016340601110812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Husain N, Bevc I, Husain M, Chaudhry IB, Atif N, Rahman A. Prevalence and social correlates of postnatal depression in a low income country. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2006;9:197–202. doi: 10.1007/s00737-006-0129-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karmaliani R, Bann CM, Mahmood MA, Harris HS, Akhtar S, Goldenberg RL, et al. Measuring antenatal depression and anxiety: findings from a community-based study of women in Hyderabad, Pakistan. Women Health. 2006;44:79–103. doi: 10.1300/J013v44n03_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Limlomwongse N, Liabsuetrakul T. Cohort study of depressive moods in Thai women during late pregnancy and 6–8 weeks of postpartum using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). Arch Womens Ment Health. 2006;9:131–8. doi: 10.1007/s00737-005-0115-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Montazeri A, Torkan B, Omidvari S. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS): translation and validation study of the Iranian version. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-7-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagpal J, Dhar RS, Sinha S, Bhargava V, Sachdeva A, Bhartia A. An exploratory study to evaluate the utility of an adapted Mother Generated Index (MGI) in assessment of postpartum quality of life in India. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:107. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakku JEM, Nakasi G, Mirembe F. Postpartum major depression at six weeks in primary health care: prevalence and associated factors. Afr Health Sci. 2006;6:207–14. doi: 10.5555/afhs.2006.6.4.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nhiwatiwa S, Patel V, Acuda W. Predicting postnatal mental disorder with a screening questionnaire: a prospective cohort study from Zimbabwe. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52:262–6. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.4.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Owoeye AO, Aina OF, Morakinyo O. Risk factors of postpartum depression and EPDS scores in a group of Nigerian women. Trop Doct. 2006;36:100–3. doi: 10.1258/004947506776593341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patel V, Rodrigues M, DeSouza N. Gender, poverty, and postnatal depression: a study of mothers in Goa, India. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:43–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pitanupong J, Liabsuetrakul T, Vittayanont A. Validation of the Thai Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale for screening postpartum depression. Psychiatry Res. 2007;149:253–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Piyasil V. Anxiety and depression in teenage mothers. J Med Assoc Thai. 1998;81:125–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pollock JI, Manaseki-Holland S, Patel V. Depression in Mongolian women over the first 2 months after childbirth: prevalence and risk factors. J Affect Disord. 2009;116:126–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Regmi S, Sligi W, Carter D, Grut W, Seear M. A controlled study of postpartum depression among Nepalese women: validation of the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale in Kathmandu. Trop Med Int Health. 2002;7:378–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rahman A, Iqbal Z, Harrington R. Life events, social support and depression in childbirth: perspectives from a rural community in the developing world. Psychol Med. 2003;33:1161–7. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703008286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stewart RC, Umar E, Kauye F, Bunn J, Vokhiwa M, Fitzgerald M, et al. Maternal common mental disorder and infant growth — a cross-sectional study from Malawi. Matern Child Nutr. 2008;4:209–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2008.00147.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Uwakwe R. Affective (depressive) morbidity in puerperal Nigerian women: validation of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;107:251–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.02477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wan EY, Moyer CA, Harlow SD, Fan Z, Jie Y, Yang H. Postpartum depression and traditional postpartum care in China: role of zuoyuezi. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;104:209–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xie RH, He G, Liu A, Bradwejn J, Walker M, Wen SW. Fetal gender and postpartum depression in a cohort of Chinese women. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65:680–4. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goldberg D, Huxley P. Common mental disorders: a biosocial model. London: Routledge; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liabsuetrakul T, Vittayanont A, Pitanupong J. Clinical applications of anxiety, social support, stressors, and self-esteem measured during pregnancy and postpartum for screening postpartum depression in Thai women. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2007;33:333–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2007.00532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fatoye FO, Adeyemi AB, Oladimeji BY. Emotional distress and its correlates among Nigerian women in late pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;24:504–9. doi: 10.1080/01443610410001722518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Adewuya AO, Eegunranti AB, Lawal AM. Prevalence of postnatal depression in Western Nigerian women: a controlled study. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2005;9:60–4. doi: 10.1080/13651500510018211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]