Abstract

Objective

To examine the impact of health-system-wide improvements on maternal health outcomes in the Philippines.

Methods

A retrospective longitudinal controlled study was used to compare a province that fast tracked the implementation of health system reforms with other provinces in the same region that introduced reforms less systematically and intensively between 2006 and 2009.

Findings

The early reform province quickly upgraded facilities in the tertiary and first level referral hospitals; other provinces had just begun reforms by the end of the study period. The early reform province had created 871 women’s health teams by the end of 2009, compared with 391 teams in the only other province that reported such teams. The amount of maternal-health-care benefits paid by the Philippine Health Insurance Corporation in the early reform province grew by approximately 45%; in the other provinces, the next largest increase was 16%. The facility-based delivery rate increased by 44 percentage points in the early reform province, compared with 9–24 percentage points in the other provinces. Between 2006 and 2009, the actual number of maternal deaths in the early reform province fell from 42 to 18, and the maternal mortality ratio from 254 to 114. Smaller declines in maternal deaths over this period were seen in Camarines Norte (from 12 to 11) and Camarines Sur (from 26 to 23). The remaining three provinces reported increases in maternal deaths.

Conclusion

Making health-system-wide reforms to improve maternal health has positive synergistic effects.

Résumé

Objectif

Étudier l’impact des améliorations apportées à l’ensemble du système de santé sur les résultats relatifs à la santé maternelle aux Philippines.

Méthodes

Une étude contrôlée longitudinale rétrospective a servi à comparer une province ayant accéléré la mise en place de réformes du système de santé avec d'autres provinces de la même région ayant introduit des reformes de manière moins systématique et moins intensive entre 2006 et 2009.

Résultats

La province dont les réformes ont été précoces a rapidement mis à niveau les installations des hôpitaux de référence de niveau de soins primaires et tertiaires, les autres provinces commençaient juste ces réformes vers la fin de la période étudiée. À la fin 2009, la province à réformes précoces avait créé 871 équipes féminines de soins de santé par rapport à 391 équipes pour la seule autre province ayant rapporté la création de ce genre d’équipe. Le montant d’allocations pour prestations maternelles versé par la Philippine Health Insurance Corporation dans la province à réformes précoces avait augmenté d’environ 45%, dans les autres provinces, la plus forte augmentation constatée était de 16%. Le taux d'accouchements médicalisés avait augmenté de 44 points de pourcentage dans la province à réformes accélérées par rapport à 9–24 points de pourcentage pour les autres provinces. Entre 2006 et 2009, le nombre réel de décès maternels constaté dans la province à réformes précoces était tombé de 42 à 18, et le taux de mortalité maternelle de 254 à 114. Des baisses moindres du nombre de décès maternels pour la même période avaient été constatées dans la province du Camarines Norte (de 12 à 11) et dans celle du Camarines Sur (de 26 à 23). Les trois autres provinces ont signalé des décès maternels en hausse.

Conclusion

Réaliser des réformes sur l’ensemble du système de santé pour améliorer la santé maternelle a des effets synergétiques positifs.

Resumen

Objetivo

Examinar el impacto de las mejoras en todo el sistema sanitario sobre los resultados de salud materna en Filipinas.

Métodos

Se empleó un estudio controlado longitudinal y retrospectivo para comparar una provincia que agilizó la aplicación de las reformas del sistema sanitario respecto a otras provincias de la misma región que introdujeron las reformas de manera menos sistemática e intensiva entre los años 2006 y 2009.

Resultados

La provincia que realizó la reforma con mayor celeridad mejoró rápidamente las instalaciones de sus hospitales de remisión de nivel primario y terciario; las otras provincias acababan de iniciar sus reformas al final del periodo de estudio. La provincia de la reforma temprana había formado 871 equipos de salud femenina antes de que acabara el 2009, en comparación con los 391 equipos de la única provincia, además de la primera, que había comunicado contar con dichos equipos. La cantidad de prestaciones materno sanitarias abonadas por la Corporación de Seguros Sanitarios de Filipinas en la provincia de la reforma temprana creció aproximadamente un 45%; en el resto de provincias, la que más aumentó lo hizo en un 16%. La tasa de partos en centros sanitarios aumentó 44 puntos porcentuales en la provincia de la reforma temprana, en comparación de los 9–24 puntos porcentuales de las otras provincias. Entre los años 2006 y 2009, el número real de defunciones maternas en la provincia de la reforma temprana descendió de 42 a 18, y la tasa de mortalidad materna, de 254 a 114. Se registraron descensos menos marcados en las defunciones maternas durante este periodo en Camarines Norte (de 12 a 11) y Camarines Sur (de 26 a 23). Las otras tres provincias notificaron aumentos en las defunciones maternas.

Conclusión

La aplicación de reformas en todo el sistema sanitario para mejorar la salud materna demostró tener un efecto sinérgico positivo.

ملخص

الغرض

فحص أثر التحسينات على نطاق النظام الصحي على نتائج صحة الأم في الفلبين.

الطريقة

تم استخدام دراسة طولانية استعادية خاضعة للمراقبة لمقارنة مقاطعة سارعت إلى تنفيذ إصلاحات النظام الصحي مع المقاطعات الأخرى في ذات الإقليم التي قدّمت إصلاحات أقل منهجية وكثافة فيما بين عامي 2006 و2009.

النتائج

قامت المقاطعة التي شهدت الإصلاح المبكر بترقية المرافق بشكل سريع في مستشفيات الإحالة الثلاثية ومستشفيات المستوى الأول؛ في حين بدأت المقاطعات الأخرى الإصلاحات بنهاية فترة الدراسة. وكونت المقاطعة التي شهدت الإصلاح المبكر 871 فريقًا صحيًا نسائيًا بنهاية عام 2009 مقارنة بعدد 391 فريقًا في المقاطعة الوحيدة الأخرى التي رفعت تقارير عن مثل هذه الفرق. ونما حجم مزايا رعاية صحة الأم التي تدفعها شركة التأمين الصحي الفلبينية في المقاطعة التي شهدت الإصلاح المبكر بنسبة 45% تقريبًا؛ بينما بلغت أكبر زيادة تالية في المقاطعات الأخرى 16%. وارتفع معدل الولادة في المرافق الصحية بنسبة 44 نقطة مئوية في المقاطعة التي شهدت الإصلاح المبكر، مقارنة بنسبة 9-24 نقطة مئوية في المقاطعات الأخرى. وفيما بين عامي 2006 و2009، انخفض العدد الفعلي لوفيات الأمهات في المقاطعة التي شهدت الإصلاح المبكر من 42 إلى 18، وانخفضت نسبة وفيات الأمهات من 254 إلى 114. كما حدثت انخفاضات صغيرة في وفيات الأمهات على مدار هذه الفترة في كامارينس نورت (من 12 إلى 11) و كامارينس سور (من 26 إلى 23). وأبلغت المقاطعات الثلاث الباقية عن زيادات في وفيات الأمهات.

الاستنتاج

يحقق إجراء إصلاحات على نطاق النظام الصحي لتحسين صحة الأم آثارًا مؤازرة إيجابية.

摘要

目的

检查菲律宾整个卫生系统的改善对妇女健康状况的影响

方法

展开回顾式纵向控制研究,将于 2006 年至 2009 年期间快速跟进卫生系统改革的一个省份与同一区域其它几个松散地进行改革的省份进行比较。

结果

先期改革省份快速升级三级和一级中心医院的设施;其它省份在研究期末才开始改革。先期改革省份在 2009 年末之前已建立 871 个妇女保健小组,而在其它仅报告有此类小组的省份中则为 391 个。先期改革省份由菲律宾卫生保险公司支付的妇女卫生保健的保险金额增幅约为 45%;其它省份中,最大的增幅为 16%。先期改革省份的住院分娩率增幅为 44%,其它省份则为 9–24%。在 2006 至 2009 年间,先期改革省份中,妇女实际死亡人数从 42 减少为 18,妇女死亡率从 254 减少为 114。在此期间,北甘马粦省(由 12 降低至 11)和南甘马粦省(由 26 降低至 23)的妇女死亡数略有减少。其它三个省份则报告妇女死亡数升高。

结论

卫生系统改革对改善妇女健康状况有积极的协同促进作用。

Резюме

Цель

Изучить, как улучшения в системе здравоохранения повлиял на результаты в области охраны здоровья матерей на Филиппинах.

Методы

Было проведено ретроспективное долгосрочное контролируемое исследование для сравнения провинции, в которой в период с 2006 по 2009 гг. внедрение реформ в системе здравоохранения шло ускоренными темпами, с другими провинциями в том же самом регионе, которые проводили реформы менее методично и интенсивно.

Результаты

Провинция с ускоренными темпами реформирования быстро модернизировала оснащение лечебно-диагностических центров третьего и первого уровней; в других провинциях реформы были начаты только к концу исследуемого периода времени. К концу 2009 г. провинция с ускоренными темпами реформирования создала 871 группу по охране женского здоровья в сравнении с 391 группой в еще одной провинции, сообщившей о создании подобных групп. Сумма выплат на охрану здоровья матерей, произведенных Филиппинской корпорацией страхования здоровья в провинции с ускоренными темпами реформирования, возросла примерно на 45%; в других провинциях самый крупный рост был зарегистрирован на уровне 16%. Доля больничных родов увеличилась на 44 процентных пункта в провинции с ускоренными темпами реформирования в сравнении с 9–24 процентными пунктами в других провинциях. В период между 2006 и 2009 гг. фактическое количество материнских смертей в провинции с ускоренными темпами реформирования снизилось с 42 до 18, а соотношение материнской смертности - с 254 до 114. Меньшее снижение количества материнских смертей за данный период времени наблюдалось в Камаринес Норте (с 12 до 11) и Камаринес Сур (с 26 до 23). Остальные три провинции сообщили о росте материнской смертности.

Вывод

Проведение реформ в системе здравоохранения с целью улучшения охраны материнства оказывает положительный синергетический эффект.

Introduction

Globally, there is renewed interest in applying systems thinking to health programming; that is, in using a broad understanding of the health system’s operations to reveal important relationships and synergies that affect the delivery of priority health services. Through a holistic understanding of a health system’s building blocks,1 systems thinking identifies where the system succeeds, where it breaks down, and what kinds of integrated approaches will strengthen the overall system and thus assist countries in reaching the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).2 This orientation towards designing, implementing and evaluating interventions that strengthen systems3,4 is directly relevant to maternal health programmes.5 Reducing maternal mortality is the health-related MDG whose progress has been “the most disappointing” to date.6 This highly complex, system-level issue must be addressed across the system rather than in isolation from it.7–12

By coordinating actions across different parts of the health system, programmes to improve maternal and neonatal health can increase coverage and reduce barriers to the use of various services. Effective programmes assemble packages of appropriate reforms in each of the six main building blocks of the health system:1,3 governance of the health sector (to provide sectoral policy and regulatory mechanisms, and partnerships with the private sector); infrastructure and technologies (to provide emergency referral centres linked to primary care providers); human resources (to scale up the availability of skilled attendance); financing (to reduce financial barriers for patients and incentivize providers), and services (to ensure quality and an appropriate configuration of maternal and neonatal health services across all levels of care, including family planning).

The Philippines faces unique challenges in aligning its health system with the needs of its inhabitants, mainly because of the country’s geography and income distribution. Many communities are located in isolated mountain regions of the country or in coastal areas that are difficult to reach. Also, there are wide disparities in the use of health services across income levels. A recent study found that 94% of women in the richest quintile delivered with a skilled birth attendant, compared with 25% in the poorest; and 84% of women in the richest quintile had a facility-based birth, compared with 13% in the poorest.6 Fertility rates also vary widely: in 2008, the total fertility rate for women in the richest quintile was 1.9, compared with 5.2 for those in the poorest quintile.13 These discrepancies contribute directly to the country’s elevated maternal mortality ratio (MMR). The MDG target is 52 deaths per 100 000 live births, yet the Philippines’ official country-estimated MMR stands at 162 – this equates to seven women dying every 24 hours from pregnancy-related causes.14 The MMR in the Philippines is higher than in other middle-income countries in the region, such as Viet Nam.

The Government of the Philippines has placed health (in general) and maternal health (in particular) high on its political agenda of reform. In 2006, recognizing that “good maternal health services can also strengthen the entire health system”, the Philippine Department of Health (DOH) launched the innovative Women’s Health and Safe Motherhood Project 2 (WHSMP2).15 This project, funded in part by the World Bank, shifted the emphasis from identifying and treating high-risk pregnancies to preparing all women for potential obstetric complications. It fast-tracked system-wide reforms in maternal health in a few selected provinces through a set of interventions, including:

sector governance: improving accountability and regulatory oversight;

infrastructure and essential medical products and equipment;

human resource development: clinical skill-building and formation of village-based women’s health teams (composed of a midwife, a pregnant woman and a traditional birth attendant [TBA]);

financing: results-based financing mechanisms and social health insurance coverage;

service delivery: availability, quantity and quality of essential health services.6

The project aimed to strengthen the ability of the health system to deliver a package of interventions, including maternal care, family planning, control of sexually transmitted infections and adolescent health services – with a priority on serving disadvantaged women. Implementation began in Sorsogon and Surigao del Sur provinces in 2006 and is scheduled for completion in 2013. The DOH developed a National Safe Motherhood Programme modelled on the design of the WHSMP2. The DOH has been introducing this national programme into other provinces as an integrated element of a larger initiative to reform the health sector. Despite slow initial implementation, progress has been made; today, Sorsogon province is seen as an early adopter of the National Safe Motherhood Programme.

This paper reports the results of a case study conducted in late 2010 to assess the impact of the National Safe Motherhood Programme by comparing progress among a set of provinces within one region.

Methods

A retrospective longitudinal controlled study design was used to compare one province where health system reforms were being fast tracked with other provinces in the same region where reforms were being introduced in a less systematic and intensive manner.

Study setting

Sorsogon is one of six provinces in the Bicol region. With a population of 709 673, it ranks as the fourth largest province (the other provinces have populations of 1 693 821, 1 190 823, 768 939, 513 785 and 232 757).16 Sorsogon is poorer than most of the other provinces in the region, with a prevalence of poverty among families of 43.5% in 2006. Masbate was the only province in the Bicol region that had a higher prevalence of poverty among its families.17

Sorsogon province was selected as the site of the World-Bank-funded health project in the Bicol region because of its low socioeconomic and maternal health status and because the local government supported the project. The province began implementing a series of reforms in 2006. Because of its participation in the World Bank project, Sorsogon has received more technical support, programme guidance and oversight from the DOH and Provincial Health Office than other provinces in the region. The World Bank loan was not a major source of revenue for Sorsogon province during the study period and was slow to begin disbursement. However, strong support from the provincial governor and mayors empowered the province to access domestic health funding. The National Safe Motherhood Programme and Maternal Mortality Reduction Initiative are being followed in the region’s other provinces but only started recently.

Data sources and collection methods

Data collection was organized around a listing of key health system indicators drawn from international best-practice standards18 and from the DOH sectoral monitoring and evaluation framework. Statistical data routinely collected for 2006–2009 were abstracted from multiple sources, including the national Field Health Service Information System, the information system of the Philippine Health Insurance Corporation (PhilHealth), the Bicol regional and provincial health budgets and records from Safe Blood Supply.

Data were manually extracted in the Bicol Regional Epidemiological Service Unit, the Bicol Regional and Provincial Health offices and the DOH and PhilHealth headquarters in Manila. Annual data were disaggregated by province, and efforts were made to obtain missing values and investigate outliers or strange values through follow-up visits to lower-level reporting units, including service delivery points.

Desk reviews were undertaken of DOH provincial ordinances, national administrative orders, project implementation plans and relevant programme documentation provided by the DOH. Selected key informant interviews were conducted with DOH and United Nations officials and with provincial and regional health offices.

Results

Regulatory oversight and governance measures

The experience gained in the design and early implementation of WHSMP2 was an important influence on the development of the programme model articulated in the DOH administrative order, “implementing health reforms to rapidly reduce maternal and newborn mortality”, which was passed for nationwide implementation in 2008.19 That administrative order spelt out key interventions covering several health system building blocks, including regulatory oversight, human resources, financing and service delivery. Subsequent administrative orders targeted actions for different building blocks, e.g. broadening the range of existing services that midwives could provide to include administration of life-saving drugs (such as magnesium sulfate and oxytocin) and other services necessary to prevent maternal and neonatal deaths.20 These administrative orders are seen as vital contributions made by the WHSMP2 through its participatory design phase and national management strategy (e.g. there is no project management unit in the DOH or Provincial Health Office).

Sorsogon’s provincial political leadership was an important element in the fast track implementation of health sector reforms and mobilization of domestic resources for health. A set of progressive ordinances released by the province provided guidance on policy and regulatory changes needed to support maternal and neonatal health. For example, in January 2009, Sorsogon province released an ordinance restricting home births and TBAs “from the practice of birth attendance or from performing deliveries of an expectant mother except when providing assistance under the immediate and direct supervision of a skilled birth attendant”.21

Infrastructure and essential medical products

We used the volume of blood supplies received by health facilities as a proxy indicator for improvements in the availability of essential medical products for maternal health services. Between 2007 and 2008, Sorsogon province reported an eightfold increase in the blood supplies (from 36 to 355 units) received by health facilities; between 2008 and 2009, an additional threefold increase (from 355 to 983 units) took place. This increase was accompanied by improvements in several ancillary services, such as community blood collection, and in blood information and transport systems. The volume of blood received in 2009 by Sorsogon was similar to that received by Camarines Sur (941 units), yet Sorsogon has less than half the population of Camarines Sur, a telling sign of the magnitude of this accomplishment.

During the study period, Sorsogon province rapidly implemented several facility renovations and upgrades using domestic health resources. These enhancements were successfully completed by the end of 2009 in the two tertiary hospitals and 20 first level referral health facilities. Twelve rural health units and one barangay (neighbourhood or village) health station were transformed into first level referral facilities, an indication that second level care has reached into remote rural areas. Only anecdotal information was available from the other provinces, but it suggested that health-facility upgrades did not start until much later (at the end of the study period).

Human resource development

The national maternal health strategy prioritizes the creation of community-based women’s health teams. In the Bicol region, Sorsogon province reported the formation of 871 women’s health teams in 541 barangay, compared with 391 in Catanduanes province. The other provinces did not report data on the formation of women’s health teams during the study period; however, anecdotal evidence suggests that, by the close of the review period, the other provinces were moving quickly with this element of the national programme model. Each member of a women’s health team receives a cash incentive through a performance-based financing mechanism.22 The payment to the TBA is intended to incentivize referral to a health facility by offsetting the potential income the TBA forfeits by making the referral. The payment to the midwife is a type of overtime salary adjustment. The payment to the pregnant woman supports transportation or other out-of-pocket expenses associated with the institutional delivery. The DOH had operational problems in delivering the first wave of performance-based grants23 but resolved these problems as experience increased. In 2009, Sorsogon province reported having disbursed 98% of the funds that had been budgeted for women’s health teams. No such funds were disbursed in the other provinces during the study period.

Sorsogon province reported that about three-quarters (74%) of the first level referral providers had successfully completed a competency-based clinical training programme. No information on clinical training was available for the comparison provinces in the Bicol region.

Financing

Sorsogon province reported spending a higher average amount on health as a percentage of the total provincial budget between 2007 and 2010 (28.76%) than did Masbate (25.73%) or Albay (13.24%) provinces (no other provinces in the Bicol region reported this information). Although the World Bank project did not set preconditions on health budget targets, the availability of loan funds to the provincial safe motherhood programme could have served as a stimulus for government to meet co-financing commitments.

Sorsogon province also realized vital achievements in expanding coverage of the national social health insurance scheme PhilHealth. Before PhilHealth can make any payments, facility accreditation is required. This requirement has been a barrier to expanding coverage because of the need for capital infrastructure improvements and on-site inspection by regulators. Sorsogon province had a threefold increase (from 5 to 17) in the number of PhilHealth-accredited facilities for outpatient care between 2006 and 2009; it also had an increase in facilities accredited for the maternity care package of benefits (from 0 to 15). Other provinces also had increases in the number of accredited facilities, but of smaller magnitude (e.g. between 2007 and 2008 these increased from 3 to 7 in Albay, from 1 to 2 in Camarines Norte and from 0 to 3 in Masbate; they remained at 3 in Camarines Sur). By the end of 2009, Sorsogon province had the largest number of PhilHealth-accredited facilities in the Bicol region.

Only one province (Albay) reported PhilHealth maternity care package insurance payments in 2006, but by 2009, three other provinces – Camarines Norte, Masbate and Sorsogon – also reported benefits. The amount of benefits paid out in Sorsogon province grew by approximately 45%, and the province moved from having the smallest amount paid out to the second largest. Among the other provinces, Albay reported a 16% increase and Camarines Norte reported a 300% increase, whereas Masbate only began making payments in 2009. However, the total amount of the 2009 payments in Camarines Norte was approximately one-half of the amount paid by Sorsogon (equivalent to 7041 and12 995 United States dollars, respectively).

Service delivery

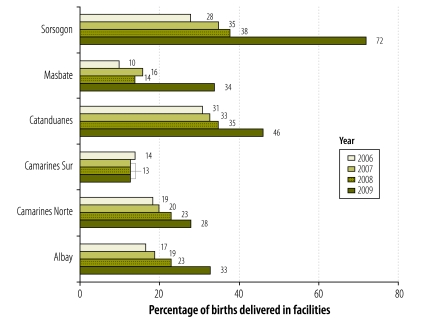

Five of the six provinces in the Bicol region reported modest increases in the number of women delivering in health facilities from 2006 to 2009 (Fig. 1). The gains in the facility-based delivery rate in the other provinces were between 9 and 24 percentage points, compared with Sorsogon province, which had a 44 percentage point increase. The largest gain occurred between 2008 and 2009, when Sorsogon reported a 34 percentage point rise in facility-based births.

Fig. 1.

Facility-based delivery rate by province, Bicol region, the Philippines, 2006–2009

Health impact: maternal mortality

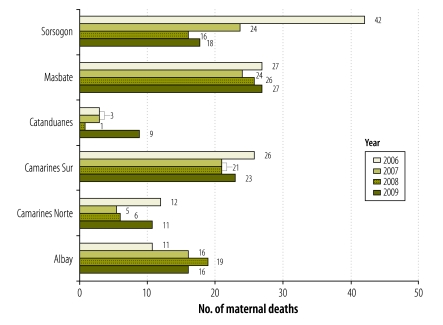

The results presented in Fig. 2 are consistent with increases in the facility-based deliveries, and with the positive changes shown in the different health system components that are critical for improving maternal health. Between 2006 and 2009, the actual number of maternal deaths in Sorsogon fell from 42 to 18; the MMR fell from 254 to 114 during the same period. Other provinces in the Bicol region reported declines in the number of maternal deaths, but of lesser magnitude. It is noteworthy that Sorsogon reported slight increases in the number of maternal deaths between 2008 and 2009, as did other provinces. A possible explanation for this situation is that an increasing trend towards facility-based birth results in fewer women dying at home and therefore in more institutional deaths being captured in the vital registration system. It could, however, indicate substandard quality of care at referral centres; this would be of serious concern and warrants close attention. In spite of the improvements, the MMR of 114 is still quite high, and Sorsogon province was still far from achieving the MDG target of 52 at the close of the reporting period of this study.

Fig. 2.

Number of maternal deaths, by province, Bicol region, the Philippines, 2006–2009

Discussion

The findings presented in this paper indicate the positive synergistic effects of increased investments (technical and financial) across multiple health system functions to improve maternal health. The constraints of the study design did not allow us to distinguish between the effects of a generalized increase in resources and the effects of applying a systems approach when selecting and organizing these additional resources. Nevertheless, the findings did give a strong indication of how maternal health programmes can coordinate a package of multifunctional interventions to achieve a rapid impact.

Use of the term systems approach draws on the “sector-wide approach” terminology to emphasize the importance of strengthening governmental systems to achieve development goals. In the Philippines, the DOH’s purposeful implementation of a World-Bank-funded project within the context of the sectoral reform programme provides a good model of aid-effectiveness principles in practice. The experience of the country’s maternal mortality reduction programme indicates the positive outcomes that can be achieved when local government leadership is coupled with investments (both domestic and foreign assistance) in multiple areas of the health system.

The systems approach to improving maternal health is not a “quick fix". The Philippines programme clearly experienced a slow start, and there were many operational delays as the country worked to refine financial mechanisms, policy development and operational guidelines. A systems approach does not mean that significant gains cannot be realized by targeted clinical interventions such as the active management of the third stage of labour, the use of magnesium sulfate to prevent eclampsia or the scale-up of skilled attendance. In the absence of a system-wide, holistic approach, maternal health programmes should not be constrained to take action in a step-by-step manner. However, the ability to sustain gains made by discrete interventions – and to scale them up – will only be realized as related functions in other health system building blocks are addressed.

Conclusion

Several challenges remain in developing health system capacity to provide maternal health care in the Philippines. For example, the health information system has not yet benefited from the sector reform programme and remains a stumbling block to effective monitoring and evaluation. The data extraction for this study was a laborious exercise; it required repeated field visits to the provincial and regional data collation centres and drew upon multiple national data repositories. The DOH has recently produced a common monitoring and evaluation framework for the health sector, but much work remains to be done on consolidating different data sources, harmonizing operational definitions and increasing the efficiencies of reporting streams. The challenges in giving remote coastal communities and isolated mountain hamlets rapid access to referral emergency-care facilities remains largely unresolved – in Sorsogon province as elsewhere in this island nation – and point to the limitations of a sector-specific response in achieving national development goals.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the input to fieldwork and research assistance from Salvador Isidro B Destura and Alexander Campbell during the conducting and reporting of this study. The responsiveness of the Sorsogon Provincial Health Office; the Center for Health Development, Bicol; and the various offices in the DOH and PhilHealth that were contacted for the extraction of data demonstrated great professionalism.

Funding:

Funding for the study was provided by The World Bank, the Manila Country Office and the Department of Reproductive Health and Research, World Health Organization, Geneva. The findings and conclusions in this paper are not the official policy of WHO, the World Bank or the Philippines DOH; the authors’ views given here should not be attributed to their organizations.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Everybody’s business – strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes: WHO’s framework for action Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atun R, de Jongh TE, Secci FV, Ohiri K, Adeyi O. Integration of targeted health interventions into health systems: a conceptual framework for analysis. Health Policy Plan. 2010;25:104–11. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czp055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Savigny D, Adam T, editors. Systems thinking for health systems strengthening Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atun R, Menabde N. Health systems and systems thinking. In: Coker R, Atun R, McKee M, editors. Health systems and the challenge of communicable diseases: experiences from Europe and Latin America Maidenhead: McGraw Hill & Open University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Béhague DP, Storeng KT. Collapsing the vertical-horizontal divide: an ethnographic study of evidence-based policy-making in maternal health. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:644–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.123117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Transforming the Philippines health sector: challenges and future directions Pasig City & Washington: The World Bank; 2011. Available from: http://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/2011/08/05/000386194_20110805013231/Rendered/PDF/635630WP0Box361516B0P11906800PUBLIC00ACS.pdf [accessed 11 October 2011]. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knippenberg R, Lawn JE, Darmstadt GL, Begkoyian G, Fogstad H, Walelign N, et al. Systematic scaling up of neonatal care in countries. Lancet. 2005;365:1087–98. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71145-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pasha O, Goldenberg RL, McClure EM, Saleem S, Goudar SS, Althabe F, et al. Communities, birth attendants and health facilities: a continuum of emergency maternal and newborn care (the global network’s EmONC trial). BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010;10:82. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-10-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenfield A, Min CJ, Freedman LP. Making motherhood safe in developing countries. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1395–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp078026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freedman LP, Waldman RJ, de Pinho H, Wirth ME, Chowdhury AM, Rosenfield A. Transforming health systems to improve the lives of women and children. Lancet. 2005;365:997–1000. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71090-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rana TG, Chataut BD, Shakya G, Nanda G, Pratt A, Sakai S. Strengthening emergency obstetric care in Nepal: the women’s right to life and health project (WRLHP). Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;98:271–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kerber KJ, de Graft-Johnson JE, Bhutta SA, Okong P, Starrs A, Lawn JE. Continuum of care for maternal, newborn, and child health: from slogan to service delivery. Lancet. 2007;370:1358–69. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61578-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Philippines National Demographic and Health Survey 2008: key findings Calverton: National Statistics Office & ICF Macro; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lavado RF, Lagrada LP, Ulep VGT, Tan LM. Who provides good quality prenatal care in the Philippines? (Discussion Paper Series No. 2010-18). Makati City: Philippine Institute for Development Studies; 2010.

- 15.Project appraisal document on a proposed loan in the amount of US$ 16.0 million to the Republic of the Philippines for a second Women’s Health & Safe Motherhood Project (Report 31456-PH). Washington: The World Bank; 2005. Available from: http://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/main?pagePK=64193027&piPK=64187937&theSitePK=523679&menuPK=64187510&searchMenuPK=64187282&theSitePK=523679&entityID=000090341_20050405090650&searchMenuPK=64187282&theSitePK=523679 [accessed 3 November 2011]

- 16.PSGC Interactive [Internet]. Region V (Bicol Region). Makati City: Philippine National Statistical Coordination Board. Available from: http://www.nscb.gov.ph/activestats/psgc/regview.asp?region=05 [accessed 3 November 2011]

- 17.Philippine Poverty Statistics [Internet]. Table 24: ranking of provinces based on poverty incidence among families: 2000, 2003 and 2006. Makati City: National Statistical Coordination Board; 2011. Available from: http://www.nscb.gov.ph/poverty/2006_05mar08/table_24.asp [accessed 26 October 2011].

- 18.Monitoring the building blocks of health systems: a handbook of indicators and their measurement strategies Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Implementing health reforms for rapid reduction of maternal and neonatal mortality (Administrative Order No. 2010-001). Naga City: Department of Health; 2008.

- 20.Administration of life savings drugs and medicines by midwives to rapidly reduce maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality (Administrative Order No. 2010-0014). Naga City: Department of Health; 2010.

- 21.Sorsogon Province, Sanggunian Panlalawigan Provincial Ordinance regulating the practices of trained birth attendants and all health workers on safe motherhood/maternal and child health programs in the province of Sorsogon (Provincial Ordinance No. 05-2008). Sorsogon: Sangguniang Panlalawigan; 2009.

- 22.Gonzalez G, Eichler R, Beith A. Pay for performance for women’s health teams and pregnant women in the Philippines Washington: United States Agency for International Development; 2010. Available from: http://www.mendeley.com/research/pay-performance-womens-health-teams-pregnant-women-philippines/ [accessed 26 October 2011]

- 23.Performance-based grants for reproductive health in the Philippines (Policy Brief WHO/RHR/11.04). Geneva: World Health Organization, Department of Reproductive Health and Research; 2011. [Google Scholar]