Abstract

The capacity of Vibrio cholerae to form biofilms has been shown to enhance its survival in the aquatic environment and play important roles in pathogenesis and disease transmission. In this study, we demonstrated that the histone-like nucleoid structuring protein is a repressor of exopolysaccharide (vps) biosynthesis genes and biofilm formation.

TEXT

Cholera is an acute waterborne diarrheal disease caused by ingestion of the bacterium Vibrio cholerae of serogroups O1 and O139. In nature, Vibrio can be found in the form of planktonic free-swimming cells or as sessile biofilm communities associated with phytoplankton and zooplankton (13, 14). The formation of such biofilm communities enhances the survival of Vibrio in the aquatic environment (8, 16, 23, 26, 32, 34). V. cholerae can also be found in the form of large biofilm aggregates in suspension of partially dormant cells that resist cultivation in conventional media but can be recovered as virulent bacteria by animal passage (8). These biofilm aggregates are more resistant to the initial low-pH stress encountered after ingestion by humans (54). As a result, mutations that block biofilm matrix exopolysaccharide biosynthesis impair colonization in the suckling mouse cholera model (9). Vibrio can associate into biofilm aggregates in the host late in infection (8). These biofilms, formed in vivo, are in a stage of transient hyperinfectivity (43) that enhances their dissemination through the fecal-oral route (24).

The development of a three-dimensional, mature biofilm involves a complex genetic program that includes the expression of motility and mannose-sensitive hemagglutinin for surface attachment and monolayer formation, as well as the biosynthesis of the exopolysaccharide matrix (Vps) (48). The genes responsible for vps biosynthesis are clustered in two operons, in which vpsA and vpsL are the first genes of operons I and II, respectively (50). These genes are regulated by several positive and negative transcription regulators. The positive regulators include the cyclic diguanylate (c-di-GMP) sensing protein VpsT (3) and the NtrC-type activator VpsR (51); the negative regulators include the master quorum sensing regulator, HapR (11, 15, 54), CytR (12), and the PhoBR two-component regulatory system (31, 41). The expression of vps genes is enhanced in response to an increase in the intracellular concentration of c-di-GMP (2, 21, 45).

The histone-like nucleoid structuring protein (H-NS) is a 15-kDa highly abundant nucleoid-associated protein that has two biological functions: DNA condensation and regulation of transcription (6). In regulation of transcription, H-NS most commonly negatively affects gene expression by binding to promoters exhibiting AT-rich, highly curved DNA regions that contain clusters of the more conserved 10-bp motif TCGATAAATT (18, 30). Binding of H-NS to a promoter apparently inhibits transcription by a bridging mechanism consisting of cross-linking DNA segments in a manner that traps the RNA polymerase within a repression loop (7). In V. cholerae, hns mutants form small colonies, exhibit diminished motility and intestinal colonization capacity, and show altered responses to environmental stresses (10, 36, 44). H-NS also silences the transcription of virulence genes by acting at different levels of the ToxR regulatory cascade, which include the toxT, tcpA, and ctxA promoters (28, 39). In this study, we examined the role of H-NS in biofilm formation.

H-NS negatively affects biofilm formation in V. cholerae.

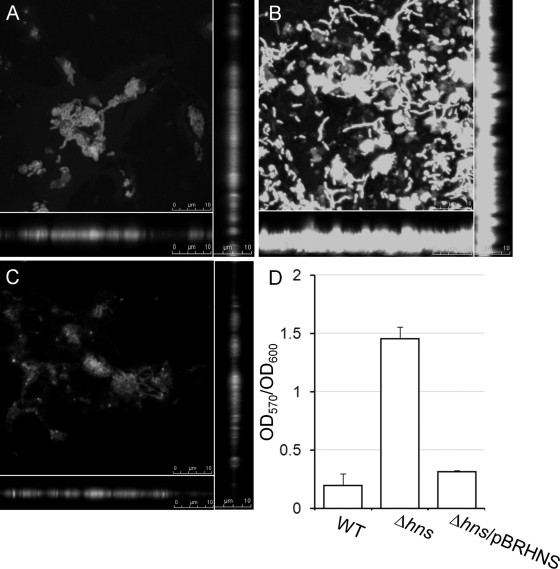

In a previous study, we described the construction of an hns deletion mutant of the El Tor biotype using the standard pCVD442 suicide vector and sucrose selection procedure (see Table 2) (5, 36). The hns deletion mutant derived from strain C7258ΔlacZ formed a large pellicle when grown in static cultures compared to findings for the wild type, suggesting the formation of enhanced biofilms. To further examine this phenotype, we compared biofilm formation between strain C7258ΔlacZ and its isogenic Δhns derivative, AJB80 (36), using confocal microscopy and crystal violet staining as previously described (19, 41). As shown in Fig. 1, the Δhns mutant adhered more and formed a thicker biofilm than the wild type. Quantification using the crystal violet assay confirmed that deletion of hns results in enhanced biofilm formation. To further confirm that the enhanced biofilm phenotype is due to the hns deficiency, we used the primers HNS1 and HNS2 (Table 1) and the Advantage 2 PCR kit (Clontech) to amplify the hns (vicH, VC1130) locus and its promoter. The PCR product was confirmed by DNA sequencing and inserted downstream of the rrn T1T2 transcription terminator (TT) in plasmid pTT3 (35). Then, the TT-hns cassette was transferred to pBR322 to yield plasmid pBRHNS (Table 1), which was introduced into strain AJB80 by electroporation. As shown in Fig. 1, strain AJB80 containing pBRHNS produced wild-type biofilm.

Table 2.

Effect of H-NS on expression of V. cholerae exopolysaccharide biosynthesis genes and their regulators

| Genea | Relative expression |

Mutant/WT ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | Δhns | ||

| vpsA∗ | 0.009 ± 0.0030 | 0.397 ± 0.2402 | 44 |

| vpsL∗ | 0.006 ± 0.0001 | 0.689 ± 0.2500 | 115 |

| vpsR∗ | 0.688 ± 0.1727 | 1.321 ± 0.1900 | 1.9 |

| vpsT∗ | 0.058 ± 0.0030 | 1.338 ± 0.3683 | 23 |

| hapR | 4.724 ± 1.4778 | 6.566 ± 0.5593 | 1.4 |

| cytR | 0.830 ± 0.1690 | 1.087 ± 0.1077 | 1.3 |

∗, mutant significantly different from wild type (P < 0.01, one-tailed t test; n = 3).

Fig 1.

Repression of biofilm formation by H-NS. Strains C7258ΔlacZ (A), AJB80 (Δhns) (B), and AJB80 complemented with plasmid pBRHNS (C) were allowed to form static biofilm in LB medium, stained with Syto-9, and examined by confocal microscopy. The center of each panel is an XY section through the biofilm. Vertical sections through the biofilm are shown to the right and bottom. (D) Quantification of biofilm formation using the crystal violet stain.

Table 1.

Strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotide primers

| Strain, plasmid, or primer | Description or sequence (5′ → 3′)a | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| C7258 | Wild type (El Tor, Ogawa) | Peru isolate, 1991 |

| C7258ΔlacZ | C7258 lacZ deletion mutant | 36 |

| AJB80 | C7258 ΔlacZ Δhns::Km | 36 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pTT3 | Transcription terminator rrnB T1T2 cloned in pUC19 | 35 |

| pKRZ1 | Plasmid containing promoterless lacZ gene | 33 |

| pTT3VpsA | 0.6-kb SphI-HindIII vpsA promoter inserted downstream of transcription terminator in pTT3 | This study |

| pVpsA -LacZ | 1.0-kb KpnI-HindIII terminator-vpsA promoter fragment inserted upstream of promoterless lacZ gene in pKRZ1 | This study |

| pTT3VpsL | 0.6-kb SphI-HindIII vpsL promoter fragment in pTT3 | This study |

| pVpsL -LacZ | 1.0-kb KpnI-HindIII terminator-vpsL fragment in pKRZ1 | This study |

| pTT3VpsR | span lang=DE>0.6-kb SphI-HindIII vpsR promoter fragment in pTT3 | This study |

| pVpsR -LacZ | 1.0-kb KpnI-HindIII terminator-vpsR fragment in pKRZ1 | This study |

| pTT3VpsT | 0.7-kb SphI-HindIII vpsT promoter fragment in pTT3 | This study |

| pVpsT -LacZ | 1.1-kb KpnI-HindIII terminator-vpsT fragment in pKRZ1 | This study |

| pBRHNS | Transcription terminator rrnB T1T2 and the hns locus were sequentially cloned in pBR322 | This study |

| Primers | ||

| HNS1 | CGCGGATCCGTGAGAAAAACAAGTGCCAC | |

| HNS2 | GATGCATGCTTCCTGAGCGAGAAGATAGC | |

| HNS-F31 | GATCGCATATGGTAATGTCGGAAATCACTAAG | |

| HNS-R32 | GATCGGCTCTTCAGCACAGAGCGAATTCTTCCAGAGA | |

| TcpA-F1 | GTTCATAATTTCGATCTCCACTCCG | |

| TcpA-R2 | GTTAACCACACAAAGTCACCTGCAA | |

| VC1922-F61 | TAGAAGGTTGACGAAACAAGCAATCA | |

| VC1922-R62 | GGTTCAACCACCATAGGTACGAGT | |

| VicH5 | GGGAAGCTTGTAATGTCGGAAATCA | |

| VicH396 | AGGAGATCTCAGAGCGAATTCTTCC | |

| VicH7 | GTTGCATGCATGTCGGAAATCACTA | |

| RpoS1020 | CTTCTGCAGTTACTTGTCGTCATCG | |

| RpsM-F51 | GCAACTGCGTGATGGTGTAGCTAA | |

| RpsM-R52 | GCTTGATCGGCTTACGCGGACC | |

| VpsA1 | GAAGCATGCGCGTAGTAGTGAATTTTTCC | |

| VpsA2 | GCGAAGCTTTACCTGATCTAACATCTCAC | |

| VpsAF | CCTTTATATCGCGCTTAAACTATATGT | |

| VpsAR | ATCCTCTTTAAAAAAGAAATTTCACAAAAT | |

| VpsL1 | GAAGCATGCGTAATGGTACGGGTTTCATA | |

| VpsL2 | GCGAAGCTTCCGTGATAGTTAGTAATGCG | |

| VpsLF1 | CTTTTCGATAAACGATACATATTATTTCT | |

| VpsLR1 | GCATGAAAATAAACTTTAGTTTACTTTTAT | |

| VpsR1 | GAAGCATGCGAGTCTGGTGATGATGAAGC | |

| VpsR2 | GCGAAGCTTAATCTGCTACTTGAGTACAG | |

| VpsRF | TGGGGCTTTTTTTATTTCCTCAAGAAA | |

| VpsRR | TCGATATTCCTTATTTTTATTGTTACGAT | |

| VpsT1 | GAAGCATGCGTTGGCATGTGGTTAAAGTG | |

| VpsT2 | GCGAAGCTTGCAAACATCAGAAAGCATTC | |

| VpsTF2 | AGGCTATGAATAAATTGAGTGGTAAGT | |

| VpsTR2 | GAAGACAAACGTTTAATCAAGCGGAA |

Restriction sites used for cloning are underlined.

H-NS negatively affects the expression of several regulators of exopolysaccharide biosynthesis.

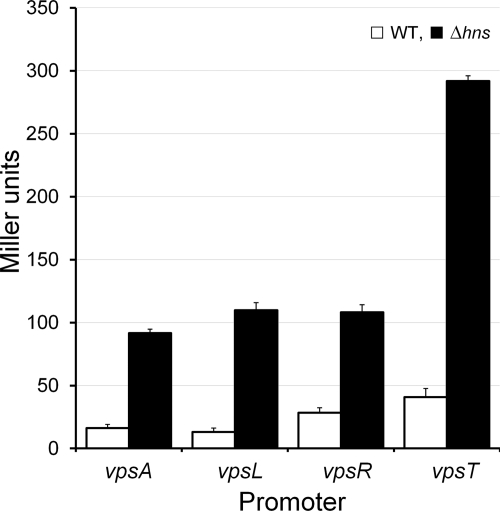

We used quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) to compare the expression of vps genes and their regulators in strain C7258ΔlacZ and AJB80 using the iScript two-step RT-PCR kit with SYBR green (Bio-Rad) and gene-specific primers previously described (19, 20). Relative expression values were calculated as 2CtTarget−CtReference, where CtTarget is the fractional threshold cycle (CT) for the target gene and the reference was the recA mRNA. As shown in Table 2, the hns mutant AJB80 expressed significantly higher levels of vpsA, vpsL, vpsT, and to a lesser extent vpsR mRNAs than the wild type. Deletion of hns did not significantly affect the expression of the vps repressors hapR and cytR. The qRT-PCR analysis was followed by construction of vpsA-, vpsL-, vpsR-, and vpsT-lacZ fusions. Primer combinations VpsA1/VpsA2, VpsL1/VpsL2, VpsR1/VpsR2, and VpsT1/VpsT2 (Table 1) were used to amplify vpsA, vpsL, vpsR, and vpsT DNA fragments containing each promoter region, respectively. The PCR products were confirmed by DNA sequencing and subcloned downstream of the TT in pTT3 (35). Finally, the TT promoter fragments were inserted upstream of a promoterless lacZ gene in plasmid pKRZ1 (33) to generate pVpsA-LacZ, pVpsL-LacZ, pVpsR-LacZ, and pVpsT-LacZ (Table 1). The resulting lacZ fusions were introduced into C7258ΔlacZ and AJB80 by electroporation, and β-galactosidase activity was measured as an indicator of promoter activity as described by Miller (25). As shown in Fig. 2, significantly elevated β-galactosidase activities were detected in the hns mutant compared to those for the wild type (P < 0.01, one-tailed t test) for all vps-lacZ fusions, with vpsT-lacZ exhibiting the strongest effect.

Fig 2.

Effect of H-NS on the expression of vpsA-, vpsL-, vpsR-, and vpsT-lacZ fusions. Strains C7258ΔlacZ (WT) and AJB80 (Δhns; filled bar) containing vpsA-, vpsL-, vpsR-, and vpsT-lacZ fusions were grown in LB at 37°C, and β-galactosidase activities were expressed in Miller units. Each value is the mean for six independent cultures. The error bars indicate the standard deviations.

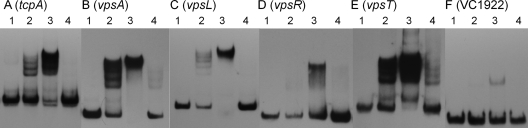

To investigate if H-NS repressed the above promoters directly, we purified H-NS and conducted DNA binding assays. To purify H-NS, the hns open reading frame (ORF) was amplified from C7258ΔlacZ genomic DNA using the primers HNS-F31 and HNS-R32 (Table 1). The amplified fragment was subcloned into similarly digested pTXB-1 (New England BioLabs) to generate pTXB1-HNS (Table 1). H-NS was then expressed and purified using the Impact kit (New England BioLabs), following the manufacturer's instructions. The purity of recombinant H-NS determined by SDS-PAGE was found to be higher than 90%. Electrophoresis mobility shift assays (EMSA) were conducted using the DIG gel shift kit, 2nd generation (Roche Applied Sciences). Binding reaction mixtures contained 3 fmol of digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled promoter DNA and 0 to 20 ng of pure H-NS in a total volume of 20 μl. After incubation (20 min, 30°C), protein-DNA complexes were separated by electrophoresis in 5% Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) polyacrylamide gels, followed by transfer to nylon membranes, and DNA was visualized using an anti-DIG Fab fragment-AP conjugate followed by chemiluminescence detection. As a positive control, the tcpA promoter was amplified using the primers TcpA-F1 and TcpA-R2. The promoter of VC1922, a gene not regulated by H-NS, was amplified using the primers VC1922-F61 and VC1922-F62 and used as a negative control. Similar to tcpA, a promoter subject to H-NS transcriptional silencing (28), H-NS exhibited strong binding to the vpsA, vpsL, and vpsT promoter (Fig. 3). H-NS binding to the vpsR promoter was weaker than that for vpsA, vpsL, and vpsT.

Fig 3.

Binding of H-NS to vps promoters. DIG-labeled DNA fragments containing the tcpA (A), vpsA (B), vpsL (C), vpsR (D), vpsT (E), and VC1922 (F) promoters were incubated with pure H-NS protein. Each labeled DNA was incubated with 0 (lanes 1), 10 (lanes 2), and 20 (lanes 3) ng of H-NS and 20 ng of H-NS plus a 62.5-fold excess of unlabeled competitor DNA (lanes 4). The spans of the promoter fragments used relative to the start codon were as follows: −306 to −83 for tcpA; −257 to −9 for vpsA; −240 to −13 for vpsL; −237 to −7 for vpsR; −224 to +3 for vpsT; and −113 to +43 for VC1922.

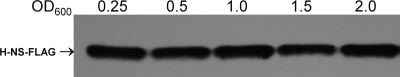

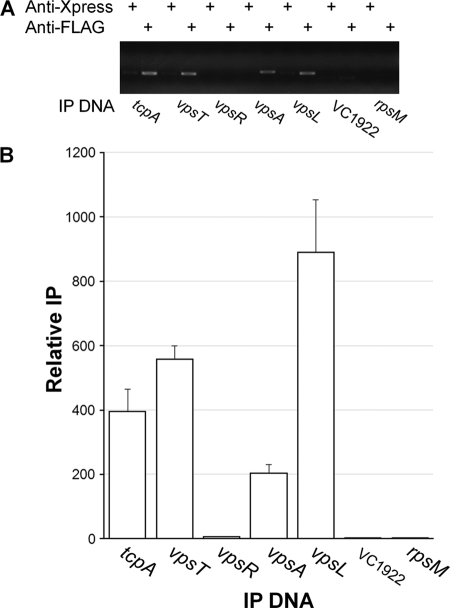

To determine H-NS occupancies at the vpsA, vpsL, vpsR, and vpsT promoters at the cellular level where other regulators could compete with H-NS for promoter access, we constructed strain C7258HNS-FLAG (Table 1) and conducted chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays. In these experiments, we used two negative controls: (i) a DNA sequence located within an ORF of the housekeeping gene rpsM and (ii) the promoter region of VC1922, to which H-NS failed to exhibit significant binding affinity in the EMSA (Fig. 3). The rationale for the rpsM ORF control was that though H-NS could bind to this sequence, such binding would not be relevant to transcription regulation and could provide a cutoff for distinguishing between H-NS binding as a repressor versus nucleoid organization. The internal rpsM probe was amplified with the primers RpsM-F51 and RpsM-R52 (Table 1). To construct C7258HNS-FLAG, the hns ORF lacking the stop codon was amplified using the primers VicH5 and VicH396. The amplification product was confirmed by DNA sequencing and cloned as a BglII-HindIII fragment in pFLAG-CTC (Sigma-Aldrich) in frame with the FLAG epitope to yield pHNS-FLAG (Table 1). The H-NS-FLAG fusion was retrieved from pHNS-FLAG by PCR with primers VicH7 and RpoS1020, containing SphI and PstI overhangs, and cloned into pTT3 (35) upstream of the TT to yield pTT3HNS-FLAG. The hns-FLAG-TT cassette was transferred to the suicide vector pCVD442 (5) to yield pCVDHNS-FLAG. Finally, pCVDHNS-FLAG was introduced into strain C7258 by conjugal transfer from S17-1λpir (4), exconjugants were selected in LB agar containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and polymixin B (100 units/ml), and correct integration into the hns locus was confirmed by PCR using primers VicH567, which anneals to DNA sequences upstream of hns not present in pCVDHNS-FLAG, and RpoS1020, which anneals to DNA encoding the FLAG epitope (Table 1). The expression of H-NS-FLAG was ascertained by Western blot analysis. To this end, strain C7258HNS-FLAG was grown in LB medium at 37°C. Samples of a volume corresponding to 1.0 OD600 (optical density at 600 nm) unit were taken at different time points and centrifuged, and the pellet was resuspended in 0.1 ml of Laemmli sample buffer. Proteins were separated using Criterion precast 10% gels (Bio-Rad) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes, and H-NS-FLAG was detected with anti-FLAG M2-peroxidase (Sigma-Aldrich) and the BM Bioluminescence Western blotting kit (Roche Applied Science). As shown in Fig. 4, H-NS was expressed at similar levels at the different time points evaluated. For H-NS promoter occupancy, 40 ml of C7258HNS-FLAG grown in LB medium to an OD600 of 0.5 at 37°C was sequentially treated with rifampin (150 μg/ml, 20 min, 37°C), 1% formaldehyde (cross-linking, 10 min, 30°C), and 227 mM glycine (30 min, 4°C). The cells were collected by centrifugation, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (PIC) and phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) (Roche Applied Science), and lysed by incubation in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl containing 20 ng/μl of RNase A, and 105 kU of ready-lyse lysozyme (Epicentre Biotechnologies) (30 min, 37°C). The lysate was mixed with 1 volume of double-strength IP buffer (200 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 600 mM NaCl, and 4% Triton X-100) containing PIC and PMSF, and DNA was broken down by sonication to a molecular size range of 150 to 1,000 bp. The cell debris was removed by centrifugation, and the lysate was diluted 10-fold in IP buffer. At this stage, a 10-μl input sample was saved as a reference and PCR efficacy control. Protein-DNA complexes were immunoprecipitated by overnight incubation at 4°C with 8 μg of anti-FLAG M2 monoclonal antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) or 8 μg of the unrelated anti-Xpress monoclonal antibody (Invitrogen) for a mock ChIP. The antibody-protein-DNA complexes were pulled down with salmon sperm DNA-treated protein A/G agarose beads (Imgenex, San Diego, CA) for 1 h at 4°C. The beads were washed with 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 250 mM LiCl, and 2% Triton X-100, collected in Spin-X centrifuge tube filters (Costar), and washed sequentially with IP buffer containing 600 mM NaCl; IP buffer and TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0] and 1 mM EDTA). The immunoprecipitated (IP) complexes were eluted from the beads by incubation at 65°C for 30 min in TE buffer containing 1% SDS. After reversal of cross-linking (4 h, 65°C), proteins were removed by treatment with 20 μg of proteinase K (1 h, 45°C). Then, IP DNA was purified using the MiniElute PCR purification kit (Qiagen) and detected by PCR and agarose gel electrophoresis using the same primer combinations designed to amplify the promoter fragments described for the EMSA. To quantitate promoter occupancies, quantitative PCR (qPCR) was conducted using the iTaq SYBR green supermix with ROX (Bio-Rad). The quantity of IP DNA was calculated as the percentage of the DNA present in the input sample using the following formula: IP = 2CtInput−CtIP, where Ct is the fractional threshold cycles (CT) of the input and IP samples. The relative IP was calculated by standardizing the IP of each sample by the IP of the corresponding mock ChIP. ChIP analysis demonstrated significant H-NS occupancies at the tcpA, vpsA, vpsL, and vpsT promoters compared to results for the negative controls (P < 0.01) (Fig. 5). Occupancies at the vpsT and vpsL promoters were similar to or higher than those at the tcpA promoter, respectively (Fig. 5). We could not demonstrate H-NS promoter occupancy at the vpsR promoter, suggesting that H-NS does not directly control the transcription of this regulator. This result is consistent with the lower H-NS binding activity detected for this promoter in the EMSA. The above-described experiments conclusively establish H-NS as a transcriptional repressor of V. cholerae exopolysaccharide biosynthesis.

Fig 4.

Expression of H-NS-FLAG in the bacterial growth curve. Strain C7258HNS-FLAG was grown in LB medium at 37°C, and samples were taken at the indicated optical densities for Western blot analysis as described in the text.

Fig 5.

ChIP analysis of H-NS binding to vps promoters. (A) Agarose gel electrophoresis of the PCR products obtained after ChIP using anti-FLAG and anti-Xpress (mock reaction) monoclonal antibodies. (B) Quantification by qPCR of H-NS occupancies at the corresponding promoter. Each value represents the mean for three experiments, and error bars indicate the standard deviations.

Discussion.

The formation of quorum sensing-regulated biofilm communities has been suggested to play a critical role in cholera ecology, pathogenesis, and disease transmission. In this study, we have provided conclusive evidences that H-NS is a transcriptional silencer of exopolysaccharide biosynthesis genes and biofilm development. Based on the above results, we conclude that H-NS directly binds to the vpsA, vpsL, and vpsT promoters to repress their expression, while its effect on vpsR transcription could be indirect. Our results add a new variable to the complex regulatory network involved in biofilm development. In transcription regulation, H-NS commonly acts as a promiscuous repressor affecting a large number of genes, particularly foreign genes acquired through horizontal gene transfer (22, 27, 29). There are no evidences that the V. cholerae vps clusters are the result of horizontal gene transfer events. However, binding of H-NS to the vpsA, vpsL, and vpsT promoters in vitro and its occupancy at these chromosomal sites were comparable to the tcpA promoter located within a pathogenicity island. Overexpression of vps genes has been shown to favor the adoption of a rugose colonial morphology (46, 50). We note that unlike hapR mutants of strain C7258, which exhibit a rugose colonial morphology (20), hns mutants show a smooth colonial morphology (data not shown). HapR is expressed at high cell density (1, 11, 15, 47, 54), while the Western blot experiment shown in Fig. 4 shows that H-NS is expressed at similar levels at low and high cell densities. Therefore, we suggest that deletion of hns enhances the expression of vps genes until the cultures enter quorum sensing mode and their expression is turned off by HapR (1, 47, 52). On the contrary, deletion of hapR allows the cell to over express vps at low and high cell densities, leading to higher exopolysaccharide accumulation and colonial rugosity. Further, deletion of hapR could also diminish H-NS levels, since HapR was found to bind to the hns promoter and enhance the expression of an hns-lux fusion (42).

It is well established that H-NS repression can be attenuated by other small nucleoid proteins, such as Fis and integration host factor (IHF) (7, 38, 40), and by non-histone-like proteins, such as the AraC-like transcriptional regulator ToxT and Shigella flexneri ParB-type virulence regulator VirB (38, 53). The regulators AphA and VpsR have been shown to bind to the vpsT promoter and enhance its expression (37, 49). It is possible that binding of AphA or VpsR to the vpsT promoter could attenuate H-NS repression at low cell density by either displacing H-NS from its binding site or preventing H-NS oligomerization along DNA to form a repression loop. Elevated expression of VpsR and VpsT in the hns mutant led to enhanced vpsA and vpsL transcription. Unfortunately, the architecture of these promoters is less understood. In the case of vpsL, a putative VpsR binding site (52) is located downstream from a high-scoring H-NS site detected using the Virtual Footprint software program (http://www.prodoric.de/vfp/vfp_promoter.php). In addition, VpsT has been shown to bind to the vpsL promoter (17). Therefore, it is possible that binding of VpsR and/or VpsT to the vpsL promoter could attenuate H-NS repression. Taken together, the involvement of H-NS in the regulation of vpsT, vpsL, and vpsA suggests the possibility of an antirepression cascade mediated by VpsR and/or VpsT to enhance exopolysaccharide expression. A more detailed characterization of these promoters is required to address the mechanism of H-NS silencing and antisilencing at these locations. Finally, it is noteworthy that VpsT and VpsR have been shown to directly sense cellular c-di-GMP (17, 37). The expression of both regulators is enhanced when the c-di-GMP pool is artificially increased by inducing the expression of a diguanylate cyclase (1). Thus, we speculate that attenuation of H-NS repression of VpsT and VpsR could be required to increase the cellular level of these receptors and potentiate c-di-GMP signal transmission.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was partially supported by National Institutes of Health research grants GM008248 and AI081039 to A.J.S. J.A.B. was a recipient of an endowment to the Southern Research Institute.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 27 January 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Beyhan S, Bilecen K, Salama SR, Casper-Lindley C, Yildiz FH. 2007. Regulation of rugosity and biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae: comparison of VpsT and VpsR regulons and epistasis analysis of vpsT, vpsR, and hapR. J. Bacteriol. 189: 388–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Beyhan S, Tischler AD, Camilli A, Yildiz FH. 2006. Transcriptome and phenotypic responses of Vibrio cholerae to increased cyclic di-GMP level. J. Bacteriol. 188: 3600–3613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Casper-Lindley C, Yildiz FH. 2004. VpsT is a transcriptional regulator required for expression of vps biosynthesis genes and the development of rugose colonial morphology in Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor. J. Bacteriol. 186: 1574–1578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. De Lorenzo V, Eltis L, Kessler B, Timmis K N. 1993. Analysis of the Pseudomonas gene products using lacIq/Ptrp-lac plasmids and transposons that confer conditional phenotypes. Gene 123: 17–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Donnenberg MS, Kaper JB. 1991. Construction of an eae deletion mutant of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli by using a positive selection suicide vector. Infect. Immun. 59: 4310–4317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dorman CJ. 2004. H-NS: a universal regulator for a dynamic genome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2: 391–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dorman CJ, Kane KA. 2009. DNA bridging and antibridging: a role for bacterial nucleoid-associated proteins in regulating the expression of laterally acquired genes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 33: 587–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Faruque SM, et al. 2006. Transmissibility of cholera: in vivo formed biofilms and their relationship to infectivity and persistence in the environment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103: 6350–6355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fong JCN, Syed KA, Klose KE, Yildiz FH. 2010. Role of Vibrio polysaccharide (vps) genes in VPS production, biofilm formation and Vibrio cholerae pathogenesis. Microbiology 156: 2757–2769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ghosh A, Paul K, Chowdhury RR. 2006. Role of the histone-like nucleoid structuring protein in colonization, motility, and bile-dependent repression of virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 74: 3060–3064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hammer BK, Bassler BL. 2003. Quorum sensing controls biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae. Mol. Microbiol. 50: 101–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Haugo AJ, Watnick PI. 2002. Vibrio cholerae CytR is a repressor of biofilm development. Mol. Microbiol. 45: 471–483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huq A, et al. 1983. Ecological relationships between Vibrio cholerae and planktonic crustacean copepods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 45: 275–283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Islam S, Drasar BS, Bradley DJ. 1990. Long-term persistence of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae 01 in the mucilaginous sheath of blue-green-algae, Anabaena variabilis. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 93: 133–139 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jobling MG, Holmes RK. 1997. Characterization of hapR, a positive regulator of the Vibrio cholerae HA/protease gene hap, and its identification as a functional homologue of the Vibrio harveyi luxR gene. Mol. Microbiol. 26: 1023–1034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Joelsson A, Liu Z, Zhu J. 2006. Genetic and phenotypic diversity of quorum-sensing systems in clinical and environmental isolates of Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 74: 1141–1147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Krasteva PV, et al. 2010. Vibrio cholerae VpsT regulates matrix production and motility by directly sensing cyclic di-GMP. Science 327: 866–868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lang B, et al. 2007. High-affinity DNA binding sites for H-NS provide a molecular basis for selective silencing within proteobacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 35: 6330–6337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liang W, Pascual-Montano A, Silva AJ, Benitez JA. 2007. The cyclic AMP receptor protein modulates quorum sensing, motility and multiple genes that affect intestinal colonization in Vibrio cholerae. Microbiology 153: 2964–2975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liang W, Silva AJ, Benitez JA. 2007. The cAMP receptor protein modulates colonial morphology phase in Vibrio cholerae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73: 7482–7487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lim B, Beyhan S, Meir J, Yildiz FH. 2006. Cyclic-di-GMP signal transduction systems in Vibrio cholerae: modulation of rugosity and biofilm formation. Mol. Microbiol. 60: 331–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lucchini S, et al. 2006. H-NS mediates the silencing of laterally acquired genes in bacteria. PLoS Pathog. 2: e81 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat. 0020081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Matz C, et al. 2005. Biofilm formation and phenotypic variation enhance predation-driven persistence of Vibrio cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:16819–16824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Merrell DS, et al. 2002. Host-induced epidemic spread of the cholera bacterium. Nature 417: 642–645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Miller JH. 1971. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 26. Morris Jr, et al. 1996. V. cholerae O1 can assume a chlorine-resistant rugose survival form that is virulent for humans. J. Infect. Dis. 174: 1364–1368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Navarre WW, et al. 2006. Selective silencing of foreign DNA with low GC content by the H-NS protein in Salmonella. Science 313: 236–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nye MB, Pfau JS, Skorupski K, Taylor RK. 2000. Vibrio cholerae H-NS silences virulence gene expression at multiple steps in the ToxR regulatory cascade. J. Bacteriol. 182: 4295–4303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Oshima T, Ishikawa S, Kurokawa K, Aiba H, Ogasawara N. 2006. Escherichia coli histone-like protein H-NS preferentially binds to horizontally acquired DNA in association with RNA polymerase. DNA Res. 13: 141–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Owen-Hughes TA, et al. 1992. The chromatin-associated protein H-NS interacts with curved DNA to influence DNA topology and gene expression. Cell 71: 255–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pratt JT, McDonough E, Camilli AA. 2009. PhoB regulates motility, biofilm, and cyclic di-GMP in Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 191: 6632–6642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rice EW, et al. 1992. Chlorine and survival of “rugose” Vibrio cholerae. Lancet 340: 740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rothmel RD, Shinabarger D, Parsek M, Aldrich T, Chakrabarty AM. 1991. Functional analysis of the Pseudomonas putida regulatory protein CatR: transcriptional studies and determination of the CatR DNA binding site by hydroxyl-radical footprinting. J. Bacteriol. 173:4717–4724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schoolnik GK, Yildiz FH. 2000. The complete genome sequence of Vibrio cholerae: a tale of two chromosomes and two lifestyles. Genome Biol. 1: reviews1016.1–reviews1016.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Silva AJ, Pham K, Benitez JA. 2003. Haemagglutinin/protease expression and mucin gel penetration in El Tor biotype Vibrio cholerae. Microbiology 149:1883–1891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Silva AJ, Sultan SZ, Liang W, Benitez JA. 2008. Role of the histone-like nucleoid structuring protein (H-NS) in the regulation of RpoS and RpoS-dependent genes in Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 190: 7335–7345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Srivastava D, Harris RC, Waters CM. 2011. Integration of cyclic di-GMP and quorum sensing in the control of vpsT and aphA in Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 193: 6331–6341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stoebel DM, Free A, Dorman CJ. 2008. Anti-silencing: overcoming H-NS-mediated repression of transcription in Gram-negative enteric bacteria. Microbiology 154: 2533–2545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stonehouse EA, Hulbert RR, Nye MB, Skorupski K, Taylor RK. 2011. H-NS binding and repression of the ctx promoter in Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 193: 979–988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Stonehouse EA, Kovacikova G, Taylor RK, Skorupski K. 2008. Integration host factor positively regulates virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 190: 4736–4748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sultan SZ, Silva AJ, Benitez JA. 2010. The PhoB regulatory system modulates biofilm formation and stress response in El Tor biotype Vibrio cholerae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 302: 22–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Svenningsen SL, Waters CW, Bassler BL. 2008. A negative feedback loop involving small RNAs accelerates Vibrio cholerae's transition out of quorum-sensing mode. Genes Dev. 22: 226–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tamayo R, Patimalla B, Camilli A. 2010. Growth in a biofilm induces a hyperinfective phenotype in Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 78: 3560–3569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tendeng C, et al. 2000. Isolation and characterization of vicH, encoding a new pleiotropic regulator in Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 182: 2026–2032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tischler AT, Camilli A. 2004. Cyclic diguanylate (c-di-GMP) regulates Vibrio cholerae biofilm formation. Mol. Microbiol. 53: 857–869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wai SN, Mizunoe Y, Takade A, Kawabata SI, Yoshida SI. 1998. Vibrio cholerae O1 strain TSI-4 produces the exopolysaccharide materials that determine colony morphology, stress resistance, and biofilm formation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64: 3648–3655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Waters CM, Lu W, Rabinowitz JD, Bassler BL. 2008. Quorum sensing controls biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae through modulation of cyclic di-GMP levels and repression of vpsT. J. Bacteriol. 190: 2527–2536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Watnick PI, Kolter RR. 1999. Steps in the development of a Vibrio cholerae El Tor biofilm. Mol. Microbiol. 34: 586–595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yang M, Frey EM, Liu Z, Bishar R, Zhu J. 2010. The virulence transcriptional activator AphA enhances biofilm formation by Vibrio cholerae by activating expression of the biofilm regulator VpsT. Infect. Immun. 78: 697–703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yildiz FH, Schoolnik GK. 1999. Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor: identification of a gene cluster required for the rugose colony type, exopolysaccharide production, chlorine resistance, and biofilm formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96: 4028–4033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yildiz FH, Dolganov NA, Schoolnik GK. 2001. VpsR, a member of the response regulators of the two-component regulatory systems, is required for expression of vps biosynthesis genes and EPS (ETr)-associated phenotypes in Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor. J. Bacteriol. 183: 1716–1726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yildiz FH, Liu XS, Heydorn A, Schoolnik GK. 2004. Molecular analysis of rugosity in a Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor phase variant. Mol. Microbiol. 53: 497–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yu RR, DiRita VJ. 2002. Regulation of gene expression in Vibrio cholerae by toxT involves both antirepression and RNA polymerase stimulation. Mol. Microbiol. 43: 119–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zhu J, Mekalanos JJ. 2003. Quorum sensing-dependent biofilms enhance colonization in Vibrio cholerae. Dev. Cell 5: 647–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]