Abstract

Thermophilic cellulases and hemicellulases are of significant interest to the biofuel industry due to their perceived advantages over their mesophilic counterparts. We describe here biochemical and mutational analyses of Caldicellulosiruptor bescii Cel9B/Man5A (CbCel9B/Man5A), a highly thermophilic enzyme. As one of the highly secreted proteins of C. bescii, the enzyme is likely to be critical to nutrient acquisition by the bacterium. CbCel9B/Man5A is a modular protein composed of three carbohydrate-binding modules flanked at the N terminus and the C terminus by a glycoside hydrolase family 9 (GH9) module and a GH5 module, respectively. Based on truncational analysis of the polypeptide, the cellulase and mannanase activities within CbCel9B/Man5A were assigned to the N- and C-terminal modules, respectively. CbCel9B/Man5A and its truncational mutants, in general, exhibited a pH optimum of ∼5.5 and a temperature optimum of 85°C. However, at this temperature, thermostability was very low. After 24 h of incubation at 75°C, the wild-type protein maintained 43% activity, whereas a truncated mutant, TM1, maintained 75% activity. The catalytic efficiency with phosphoric acid swollen cellulose as a substrate for the wild-type protein was 7.2 s−1 ml/mg, and deleting the GH5 module led to a mutant (TM1) with a 2-fold increase in this kinetic parameter. Deletion of the GH9 module also increased the apparent kcat of the truncated mutant TM5 on several mannan-based substrates; however, a concomitant increase in the Km led to a decrease in the catalytic efficiencies on all substrates. These observations lead us to postulate that the two catalytic activities are coupled in the polypeptide.

INTRODUCTION

Plant biomass, a renewable resource targeted for bioenergy production, is mainly composed of cellulose and hemicellulose. To completely hydrolyze plant cell wall polysaccharides into simple sugars, a suite of cellulases and hemicellulases are required to operate in synergy (25, 39). Thermostable cellulases and hemicellulases are appealing to the biofuel industry due to their perceived advantages over their mesophilic counterparts. As examples, thermostable enzymes are more compatible with lignocellulose pretreatment using heat, they have a longer shelf-life at room temperature, and enzymatic pretreatment at high temperatures reduces the likelihood of microbial contamination (60).

Recently, the complete genome sequencing of a thermophilic cellulose- and xylan-degrading bacterium (59), Caldicellulosiruptor bescii (previously classified as Anaerocellum thermophilum) (58), was accomplished (GenBank accession number CP001393) (12, 30). The bacterium has been demonstrated to ferment crystalline cellulose, xylan, and insoluble extracts of the bioenergy feedstock switchgrass (12). In corroboration with this finding, within the genome of C. bescii is a large gene cluster in which nine genes were predicted to encode enzymes that either degrade cellulose or hemicellulose (12).

In the present study biochemical and mutational analyses were used to decipher the contribution of the different modules found in the large polypeptide encoded by ORF1952 (GenBank accession number ACM60953) of C. bescii. The gene product of ORF1952, which was designated CbCel9B/Man5A (also referred to as CelC-ManB, Athe_1865) (35), has a glycoside hydrolase family 9 (GH9) module at the N terminus and a GH5 module at the C terminus. Located between the two modules are three carbohydrate-binding modules (CBMs). GH9 family enzymes have an (α/α)6-barrel fold, and this family of enzymes is known to contain members that exhibit different enzymatic activities, including endoglucanase (45), cellobiohydrolase (15), 1,4-β-d-glucan glucohydrolase (43), β-glucosidase (40), and exo-β-glucosaminidase (23). The GH5 family of enzymes have an (β/α)8-barrel fold, and this family also encodes diverse enzymatic activities, including endoglucanase (16), mannanase (20), mannosidase (20), xylanase (14), chitosanase (50), glucosidase (11), licheninase (25), fucosidase (61), galactanase (44), endoglycoceramidase (9), and mannan transglycosylase (6). The binding cleft in GH9 catalytic modules can hold six sugar molecules, among which four subsites (−4 to −1) are at the nonreducing end and the two remaining subsites are at the reducing end (+1 to +2) (45). Similar arrangement of subsites are present in the binding cleft of GH5 catalytic modules (21, 48). Hydrophobic stacking interactions between aromatic residues and the sugar rings and hydrogen bonding between polar residues and the sugars are crucial for hydrolysis by these enzymes. All three CBMs found in the CbCel9B/Man5A are members of CBM family 3 (CBM3). The CBM3 modules are divided into four subfamilies based on the difference of the key planar linear strip aromatic or polar amino acid residues on the substrate binding surface (52). The CBM3a subfamily is only found associated with scaffoldins, CBM3b is associated with free enzymes, CBM3c is mainly linked to GH9 catalytic modules, and CBM3d is a newly identified module from Cellulosilyticum ruminicola (8).

Polypeptides containing GH9 or GH5 modules that exhibit very high homology with the C. bescii CbCel9B/Man5A modules are found in the genomes of other Caldicellulosiruptor species (GH9: C. saccharolyticus, C. obsidiansis, C. kronotskyensis, C. kristjanssonii, and C. lactoaceticus; GH5: C. saccharolyticus, C. obsidiansis, C. kronotskyensis, and C. kristjanssonii); however, the modular arrangement described for the gene product of ORF1952 (GH9, three CBM3s, and GH5) is only observed in the genomes of C. bescii and C. obsidiansis. By studying the catalytic activities present in the wild-type polypeptide and its various mutants, we gained insight into how CbCel9B/Man5A may aid C. bescii to access fermentable sugars from polysaccharides, especially those present in plant cell walls.

Our results demonstrated that CbCel9B/Man5A enables the thermophilic bacterium to release fermentable sugars from β-1,4-glucosidic and β-1,4-mannosidic polysaccharides. However, based on kinetic analysis, the highest catalytic activity was detected with locust bean gum, a polysaccharide composed of a β-1,4-linked mannose backbone with α-linked galactose side chains. Our truncated mutants demonstrated that the GH9 and the GH5 modules harbor the activities for cleavage of the β-1,4-glucosidic and β-1,4-mannosidic linkages, respectively. Separation of the catalytic modules resulted in a higher turnover rate or catalytic efficiency in each module, suggesting that the two catalytic domains are coupled in the wild-type enzyme. Future structural studies on enzyme substrate complexes should enhance our understanding of how the two catalytic modules function together in the polypeptide. The thermostability of CbCel9B/Man5A and its potential application in plant cell wall depolymerization in the biofuel industry are also discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning of the gene encoding CbCel9B/Man5A wild type and its truncation mutants.

The Escherichia coli strain JM109 (Promega) was used for gene cloning, plasmid maintenance, and propagation throughout the present study. The ORF1952 gene product (GenBank accession number ACM60953) was designated CbCel9B/Man5A since a different polypeptide in C. bescii (CelA; GenBank accession number Z86105) containing a GH9 catalytic module has already been characterized from this bacterium (65). In contrast, the Man5A module represents the first GH5 module demonstrated to exhibit mannanase activity from this bacterium. The coding sequences for CbCel9B/Man5A wild type and its truncation mutants (Fig. 1A) were amplified from the genomic DNA of C. bescii DSM 6725 by PCR using PrimeSTAR HS DNA polymerase (Takara, Shiga, Japan) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material for primer sequences). The PCR products were cloned into the pET-46 Ek/LIC vector according to the protocols described by the manufacturer (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and also described in our previous report (39).

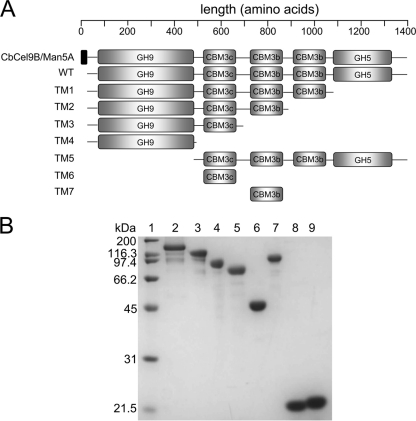

Fig 1.

(A) Schematic structures of the CbCel9B/Man5A wild type and its truncation mutants. The signal peptide is shown in filled rectangle. GH9, family 9 glycoside hydrolase domain; GH5, family 5 glycoside hydrolase domain; CBM3c, family 3 type C carbohydrate binding module; CBM3b, family 3 type B carbohydrate binding module. (B) SDS-PAGE of the CbCel9B/Man5A wild type and its truncation mutants. Lane 1, protein molecular mass marker; lane 2, CbCel9B/Man5A wild type; lane 3, CbCel9B/Man5ATM1; lane 4, CbCel9B/Man5ATM2; lane 5, CbCel9B/Man5ATM3; lane 6, CbCel9B/Man5ATM4; lane 7, CbCel9B/Man5ATM5; lane 8, CbCel9B/Man5ATM6; lane 9, CbCel9B/Man5ATM7. Portions (2 μg) of each enzyme were analyzed on an SDS–12% polyacrylamide gel.

Gene expression and protein purification.

The recombinant pET-46 Ek/LIC plasmids harboring sequences coding for either the CbCel9B/Man5A wild type or one of its truncation variants were transformed individually into E. coli BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIPL competent cells (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and selected on a lysogeny broth (LB) agar plate supplemented with 100 μg of ampicillin/ml and 50 μg of chloramphenicol/ml. After an overnight incubation, a single colony was inoculated into 10 ml of LB containing the same antibiotics and incubated at 37°C with shaking for 6 h. This preculture was transferred to a 1-liter LB medium, and the culturing was continued until the optical density at 600 nm reached 0.3. The temperature was then decreased to 16°C, and IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) was added to the culture at a 0.1 mM final concentration. After further culturing at 16°C for 16 h, the cells were harvested by centrifugation. For the CbCel9B/Man5A wild type, the cell pellet was resuspended in a lysis buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.8], 750 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 20 mM imidazole, 1.25% Tween 20). For CbCel9B/Man5ATM1, the cell pellet was resuspended in a different lysis buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.8], 100 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 10 mM imidazole, 1.25% Tween 20). For the other mutants, the cell pellet was resuspended in a lysis buffer without imidazole (50 mM Tris-HCl, 300 mM NaCl [pH 7.5]). The resuspended cell pellets were then passed through an EmulsiFlex C-3 cell homogenizer (Avestin, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada). The supernatant containing the cell extract was collected after centrifugation at 12,857 × g for 20 min, and the recombinant proteins were purified as described below.

All recombinant proteins were purified by immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography using a cobalt-charged resin (Talon Metal Affinity resin; Clontech, Mountain View, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For the CbCel9B/Man5A wild type, the eluted protein was dialyzed against a protein storage buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl [pH 7.5]). Since proteins encoded by C. bescii were expected to be thermostable, the recombinant protein in the storage buffer was subsequently heated at 75°C for 10 min and centrifuged at 25,000 × g for 20 min to precipitate any coeluting thermolabile host proteins. The recombinant protein was further purified by gel filtration chromatography using an ÄKTAxpress TWIN fast protein liquid chromatograph system equipped with a Hiload 16/60 Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). The buffer for gel filtration chromatography was the protein storage buffer described above. The CbCel9B/Man5ATM1 was purified as described for the wild-type protein except for the heating step, which was carried out for 20 min. For the other mutants, the recombinant proteins eluted from the Talon resin were directly applied to gel filtration chromatography.

Activity screening of CbCel9B/Man5A on polysaccharides.

Screening for the capacity of CbCel9B/Man5A to hydrolyze polysaccharides with different glycosidic linkages was carried out by incubating 0.5 μM CbCel9B/Man5A with 10 mg of Avicel/ml, sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC-Na), lichenin, mannan, konjac glucomannan (KGM; Megazyme), wheat arabinoxylan (WAX), birchwood xylan (BWX), oat-spelt xylan (OSX), and xyloglucan. In addition, the enzyme was incubated with 2.5 mg of phosphoric acid swollen cellulose (PASC)/ml, locust bean gum (LBG), and guar gum. Each reaction was carried out in 50 mM phosphate buffer–150 mM NaCl (pH 6.5) at 75°C for 15 h. The reducing sugars released were quantified using the 4-hydroxybenzoic acid hydrazide (pHBAH; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) assay (31). Avicel, BWX, OSX, and guar gum were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. CMC-Na was purchased from Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium). Lichenin, mannan, KGM, WAX, and xyloglucan were purchased from Megazyme (Wicklow, Ireland). Glucose (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as the standard to derive a prediction equation for the reducing sugar assay.

Determination of optimal pH and temperature.

Two buffers were used for pH profiling of CbCel9B/Man5A: 50 mM sodium citrate–150 mM NaCl (pH 4.0 to 6.0) and 50 mM Na2HPO4-NaH2PO4–150 mM NaCl (pH 6.5 to 8.0). To determine the optimal pH of the enzymes on a representative cellulose, 0.5 μM CbCel9B/Man5A wild type or one of its truncation mutants (TM1, TM2, and TM3) or 40 μM TM4 was incubated with 2.5 mg of PASC/ml in each buffer at a given pH at 75°C, and the activities in a 10-min assay were determined. The reducing sugars released were measured by using the pHBAH assay. For determination of optimal temperature, each enzyme was incubated with 2.5 mg of PASC/ml at its optimal pH at different temperatures ranging from 40 to 95°C with a 5°C interval. The optimal pH and temperature for mannanase activity were determined as described above, except for the replacement of PASC with mannan as the substrate and a change of the enzyme concentration to 12.5 nM.

Enzymatic assays.

The specific activities of the CbCel9B/Man5A wild type and its mutants on Avicel and filter paper were determined at 75°C in the optimal buffer for the enzymes. The enzyme concentrations were 0.3 μM for each protein except for TM4 (5 μM). At different time intervals in a 90-min assay, samples were taken out, and the products released were determined as the amount of reducing ends present in the reaction mixture. The specific activities were determined in the region where the relation of reducing sugar released versus time was linear.

The Michaelis-Menten kinetic parameters of CbCel9B/Man5A wild-type and its mutants on PASC, locust bean gum, guar gum, and konjac glucomannan were determined in a 30-min assay. An appropriate concentration of each enzyme was incubated with a range of substrate concentrations at 75°C. The initial rates of release of reducing ends were determined and plotted against substrate concentrations, and the apparent kinetic parameters were estimated by the Michaelis-Menten equation using the software GraphPad Prism 5.01 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA).

Time course hydrolysis of PASC.

A portion (2.5 mg) of PASC/ml was incubated with 0.5 μM CbCel9B/Man5A WT, TM1, and TM5 at 75°C. At different time intervals (0 min, 2 min, 10 min, 60 min, 4 h, and 24 h), aliquots were taken and subjected to high-performance anion exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection (HPAEC-PAD) analysis to detect end products as described earlier (39).

Analyses of oligosaccharides hydrolysis and transglycosylation activity.

Glucose, cello-oligosaccharides (cellobiose, cellotriose, cellotetraose, cellopentaose, and cellohexaose), mannose, and manno-oligosaccharides (mannobiose, mannotriose, mannotetraose, mannopentaose, and mannohexaose), each at a final concentration of 1 mg/ml, were incubated with 0.1 μM CbCel9B/Man5A wild type, CbCel9B/Man5ATM1, and CbCel9B/Man5ATM5 in a citrate buffer (10 mM sodium citrate, 150 mM NaCl [pH 5.5]) at 75°C for 14 h. The total reaction volume was 40 μl. The reaction products were dried using a SpeedVac concentrator (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) and dissolved in 3.5 μl of H2O, and 1 μl of the products was analyzed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) using a 250 μm thick Whatman silica gel 60A (Maidstone, England). The TLC method was the same as described in our earlier report (39). Briefly, reaction products were spotted on a 10-cm-by-20-cm TLC plate and kept at room temperature for 15 min until the plate was dry. The plate was developed using a solution containing n-butanol–acetic acid–H2O with a ratio of 10:5:1 as the mobile phase. After development, the plate was dried, and the hydrolyzed products were visualized by spraying the plate with a 1:1 (vol/vol) mixture of methanolic orcinol (0.2% [wt/vol]) and sulfuric acid (20% [vol/vol]). The plate was incubated at 80°C for 10 to 15 min until spots representing the sugars could be clearly seen. Mannose and cellobiose were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Cello-oligosaccharides and manno-oligosaccharides were purchased from Megazyme (Wicklow, Ireland).

Thermostability assay.

The thermostability of CbCel9B/Man5A and its truncation mutants harboring cellulase activity were determined by incubating the enzymes at 75, 80, and 85°C (WT, TM1, TM2, and TM3) or at 45, 50, and 55°C (TM4) on a Veriti 96-well thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). At different time points, aliquots were taken from the tubes and residual enzymatic activity was determined with PASC as the substrate.

Site-directed mutagenesis and circular dichroism.

For site-directed mutagenesis, a QuikChange multi-site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. One hundred nanograms of the plasmid encoding CbCel9B/Man5ATM3 was used as the template in the PCR amplification. The reaction mixture contained 100 ng of the mutagenic primer, 1 μl of deoxynucleoside triphosphate mix, 0.75 μl of QuikSolution, and 1 μl of QuikChange multi-enzyme blend. The nucleotide sequences of the mutagenic primers used for mutagenesis are given in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The PCR amplification steps were carried out as follows: an initial denaturation at 95°C for 1 min, followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 65°C for 15 min. The PCR product was digested with DpnI (New England Biolabs) at 37°C for 4 h to degrade the parental plasmid DNA. The product from the DpnI digestion was used in electrotransforming JM109 competent cells using a Gene Pulser Xcell electroporation system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The E. coli cells were spread on LB plates containing 100 μg of ampicillin/ml and incubated at 37°C overnight. Single colonies were inoculated in 7 ml of LB medium supplemented with 100 μg of ampicillin/ml and cultured for 10 h. The plasmids were extracted from the recombinant E. coli cells, and the inserts were sequenced (W. M. Keck Center for Comparative and Functional Genomics, University of Illinois) to confirm the presence of the desired mutation. Circular dichroism scans of mutated proteins were carried out using a J-815 CD spectropolarimeter (Jasco, Japan) equipped with a constant-temperature cell-holder as described in our previous report (47). Briefly, proteins (0.2 mg/ml) in a phosphate buffer (10 mM sodium phosphate [pH 7.0]) in a 1-mm quartz cuvette were kept at 25°C for 5 min before scanning. The measurements started from an initial wavelength of 260 nm to a final wavelength of 190 nm with a setting of the wavelength step as 0.1 nm. The secondary structural elements of the proteins were analyzed on the Dichroweb website (http://dichroweb.cryst.bbk.ac.uk/html/home.shtml) using an algorithm of CDSSTR with a reference Set 4 optimized for 190 to 240 nm (56, 57).

Measurement of reducing sugar in the soluble and insoluble fraction of hydrolyzed filter paper.

The reducing sugars in the soluble and insoluble fractions of filter paper hydrolysis products were determined as described by Irwin et al. (27). The CbCel9B/Man5A wild-type and its mutants (0.5 μM each except for TM4, which was at 10 μM) were incubated with five plates of Whatman no. 1 filter paper (0.6 cm in diameter) in a citrate buffer (pH 5.5) at 75°C (for TM4, the temperature was 45°C, since this construct has lower thermostability) in 200 μl. The mixtures were shaken end-over-end for 16 h. The reaction products were centrifuged, and the supernatants (soluble fractions) were analyzed for the amounts of reducing ends. For reducing sugar determination in the insoluble fraction, the filter papers were initially washed four times each with 1 ml of the citrate buffer. Two hundred microliters of the citrate buffer was then added to the insoluble fraction (precipitated filter paper), followed by assaying for reducing ends through the pHBAH method.

Binding of CbCel9B/Man5A wild type and its truncated mutants to cellulose.

For qualitative measurements of the capacity of the individual polypeptides to bind to cellulose, 30 μg of CbCel9B/Man5A wild type and its mutants was incubated with 40 mg of Avicel cellulose/ml or 2.5 mg of PASC/ml in 50 mM Tris-HCl–150 mM NaCl (pH 7.5). The mixture was shaken end over end at 4°C for 1 h. The bound and unbound proteins were separated by centrifugation of the mixture at 25,000 × g for 3 min. The cellulose pellet was washed four times with 1 ml of buffer (50 mM Tris buffer–150 mM NaCl [pH 7.5]). A portion (70 μl) of 1× SDS-PAGE loading buffer was added to the pellet and boiled for 5 min to release bound proteins. The protein present in one tenth of the volume of the supernatant (unbound protein), and the cellulose pellet (bound protein) was examined by a SDS–12% PAGE.

For quantitative binding assay, different concentrations of proteins were mixed with 2 mg of Avicel/ml in 50 mM Tris-HCl–150 mM NaCl (pH 7.5) buffer in a 2-ml tube. As a control, proteins of the same concentrations were incubated with the buffer without Avicel in the tube. After 1.5 h end-over-end incubation at 4°C, the mixtures were centrifuged at 25,000 × g for 3 min. The protein concentrations in the supernatant were determined using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay reagent kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). Taking the protein concentration from the tube without cellulose as the total protein, the concentrations of bound protein were obtained by subtracting the protein concentration of the sample with cellulose from the total protein concentration. For determination of the binding parameters, the Michaelis/Langmuir equation, i.e., qad/q = Kp × qmax/(1 + Kp × q), as described in our previous report (62) was used. The qad in the equation represents the amount of bound protein (nmol of protein per g of Avicel), q is the free protein (μM), Kp is the dissociation constant (μM), and qmax is the maximal amount of bound protein to Avicel. The calculation of the binding parameters was carried out with GraphPad Prism 5.01.

Amino acid sequence alignment.

The amino acid sequences of the GH9 catalytic module of the Clostridium cellulolyticum Cel9G (GenBank accession number AAA73868) (36) and that of the Thermobifida fusca Cel9A (GenBank accession number AAB42155) (45) were retrieved from the Carbohydrate Active enZYme database (http://www.cazy.org/) and the GenBank database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/) and aligned with the GH9 sequence of CbCel9B/Man5A by using ClustalX (http://www.clustal.org). Similarly, the amino acid sequences of the CBM3c modules from the characterized cellulases of different bacterial sources in the published literature, as well as from the unpublished homologs of CbCel9B/Man5A in the genus Caldicellulosiruptor, were aligned. These include the following: ADQ45731, putative cellulase of Caldicellulosiruptor kronotskyensis; ABP66693, putative cellulase of Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus; ADL42950, putative Caldicellulosiruptor obsidiansis cellulase/mannan endo-1,4-β-mannosidase; AAK06394, CelE of Caldicellulosiruptor sp. strain Tok7B.1 (18); AAA73868, Cel9G of Clostridium cellulolyticum (36); AAC38572, EngH of Clostridium cellulovorans (49); CAA39010, Cel9Z of Clostridium stercorarium (28); ABX43720, Cel9 of Clostridium phytofermentans (51, 64); ABN51860, Cel9I of Clostridium thermocellum ATCC 27405 (66); CAB38941, Cel9B of Paenibacillus barcinonensis (42); BAB33148, CelQ of Clostridium thermocellum F1 (2); AAA23086, CenB of Cellulomonas fimi (37); AAW62376, CBP105 of Cellulomonas flavigena (38); and AAB42155, Cel9A of Thermobifida fusca (26, 45). The aligned sequences were analyzed using BOXSHADE 3.21 (http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/BOX_form.html) with a default setting of the fraction of sequences parameter as 0.5.

RESULTS

Cloning, expression, and purification of CbCel9B/Man5A and its mutants.

A gene (ORF1952) encoding a large protein (a 1,360-amino-acid polypeptide) composed of an N-terminally located GH9 catalytic module and a C-terminally located GH5 catalytic module was cloned from C. bescii and expressed in E. coli cells (Fig. 1A). Also located between the two catalytic modules were one CBM3c and two CBM3b modules with 100% amino acid sequence identity to each other. The gene also encodes a signal peptide ahead of the GH9 module, and the gene product is reported to be secreted into the extracellular space (35). The wild-type protein was initially screened for activity on several polysaccharides. Interestingly, it was discovered that the protein has hydrolytic activities for different cellulosic and mannan-like substrates, including Avicel, phosphoric acid swollen cellulose, lichenin, mannan, locust bean gum (LBG), guar gum, konjac glucomannan, wheat arabinoxylan (WAX), and oat spelt xylan (OSX) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The enzymatic activities on the glucose-based (PASC and lichenin) and the mannose-based (mannan, guar gum, locust bean gum, and konjac glucomannan) substrates were, however, higher than those on the xylose-based (WAX and OSX) substrates (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

Several truncation mutants were made from the polypeptide to determine the contribution of its different modules to the function of CbCel9B/Man5A. Attention was focused on the GH9 module due to its capacity to degrade cellulosic substrates and also because the Man5A module occurs in another polypeptide being biochemically characterized in detail from the same bacterium (C. bescii) in our lab (J. Zhang et al., unpublished data). The identity between the two GH5 modules of the two polypeptides is 99.6%. Thus, a wild-type protein, lacking the signal peptide (WT), and several truncation mutants, mostly containing the GH9 module (TM1, TM2, TM3, TM4, TM5, TM6, and TM7) were systematically constructed for functional analysis.

As shown in Fig. 1A, TM1 contained the GH9 module and the three CBMs, TM2 contained the GH9 module and two CBMs, TM3 contained the GH9 module and one CBM (CBM3c), and TM4 was made up of only the GH9 module. The truncated mutant TM5 was composed of the three CBMs linked to the GH5 module, whereas TM6 and TM7 were composed of the CBM3c and CBM3b, respectively. The SDS-PAGE results in Fig. 1B show that all protein constructs were successfully expressed as soluble proteins and purified close to homogeneity. The predicted sizes of the proteins were in accordance with obtained SDS-PAGE results.

Determination of optimal pH, optimal temperature, and thermostability.

The optimal pH for CbCel9B/Man5A WT, TM1, TM2, and TM3 with PASC, as substrate, were in the range of 5.0–5.5 and the optimal temperature for each of these proteins was 85°C. In the case of TM4, the optimal pH and temperature with PASC were 6.5 and 55°C, respectively. The thermostability assays were carried out on the wild-type and truncation mutants harboring cellulase activities at 75°C, 80°C, and 85°C (for wild-type, TM1, TM2, and TM3) or at 45°C, 50°C, and 55°C (for TM4). The residual activities of WT, TM1, and TM2 at 80°C and 85°C after 24 h of incubation and that of TM3 at 85°C were all less than 20% except for TM3 treated at 80°C, which retained 61.8% activity. At 75°C, the residual activities of WT, TM1, TM2, and TM3 after 24 h of incubation were 43.1%, 75.7%, 53.6%, and 101.7%, respectively (Supplemental Fig. 2). Deletion of CBM3c dramatically reduced the thermostability of the enzyme. The truncated mutant TM4 remained stable at 45°C and 50°C, but the enzyme rapidly lost its activity at temperatures above 55°C (Supplemental Fig. 2). The pH and temperature optima were also determined for hydrolysis of mannan substrates. For the wild-type enzyme, the optimal pH and temperature for hydrolysis of the mannan substrates were 5.5–6.5 and 90°C, respectively, and for TM5 the values were 6.5 and 90°C, respectively (data not shown). The thermostability of TM5 using mannan as substrate was not determined in the present study.

Hydrolysis of phosphoric acid swollen cellulose, cello- and manno-oligosaccharides by CbCel9B/Man5A and its mutants.

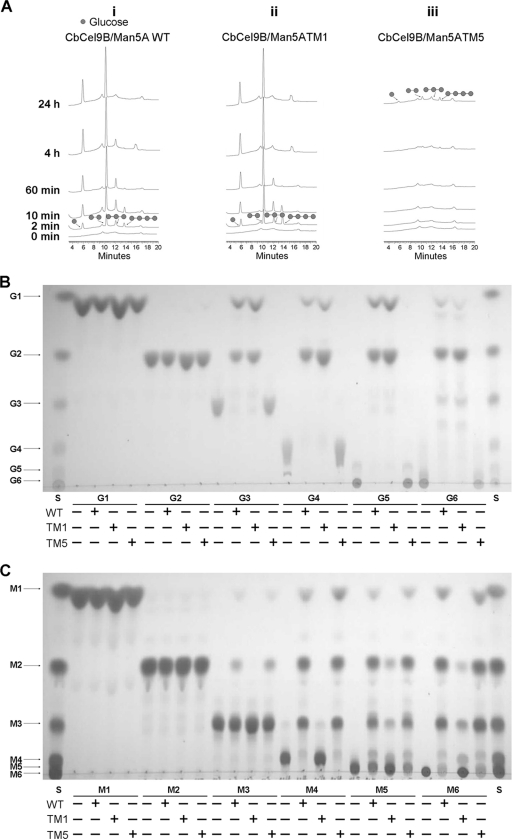

The capacity of the wild-type CbCel9B/Man5A and its TM1 and TM5 mutants, representing the mutants that harbored the GH9 module with the 3 CBMs and the GH5 module together with the 3 CBMs (Fig. 1A), were investigated in a time course approach for hydrolysis of PASC. As shown in the chromatograph in Fig. 2A, release of products, mostly cellobiose and glucose, was observed for the wild-type (i) and the TM1 (ii) mutant, which contains the GH9 module. Very little to no hydrolysis of PASC was detected from TM5 (iii) (the construct with the GH5 module). By further testing hydrolysis of cello-oligosaccharides, it was confirmed that the β-1,4-glucose linkage cleaving activity was controlled by the GH9 domain (Fig. 2B). The wild-type protein and TM5 showed hydrolysis of manno-oligosaccharides from degree of polymerization (DP) of 3 and larger (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, TM1 also showed activity on manno-oligosaccharide substrates of DP of 5 or larger, albeit the activity was lower than the wild-type enzyme and the TM5 mutant. No transglycosylation activities were found for the wild-type, TM1, and TM5 on glucose, cello-oligosaccharides, mannose, and manno-oligosaccharides under the conditions tested.

Fig 2.

Hydrolysis patterns of CbCel9B/Man5A wild type, TM1, and TM5 on PASC (A), and reactions of CbCel9B/Man5A wild type, TM1, and TM5 with glucose and cello-oligosaccharides (B) and with mannose and manno-oligosaccharides (C). (A) Time course hydrolysis of PASC by CbCel9B/Man5A WT (i), TM1 (ii), and TM5 (iii). PASC (2.5 mg/ml) was incubated with 0.5 μM CbCel9B/Man5A WT, TM1, and TM5 at 75°C. At different time intervals (0 min, 2 min, 10 min, 60 min, 4 h, and 24 h), samples were taken out and applied to HPAEC-PAD analysis. (B and C) TLC analysis of glucose and cello-oligosaccharides (B) and mannose and manno-oligosaccharides (C) reacted with CbCel9B/Man5A WT, TM1, and TM5. The reactions were carried out by incubating 0.1 μM (each) CbCel9B/Man5A WT, TM1, and TM5 with 1 mg of glucose and cello-oligosaccharides/ml or 1 mg of mannose and manno-oligosaccharides/ml in a total volume of 40 μl. The incubation was kept at 75°C for 14 h. The reaction products were dried and added with 3.5 μl of H2O. A 1-μl portion of the product was subjected to TLC analysis. G1, glucose; G2, cellobiose; G3, cellotriose; G4, cellotetraose; G5, cellopentaose; G6, cellohexaose. M1, mannose; M2, mannobiose; M3, mannotriose; M4, mannotetraose; M5, mannopentaose; M6, mannohexaose. S, cello-oligosaccharides (B) or manno-oligosaccharides (C) standard.

Activities and kinetic parameters of CbCel9B/Man5A and its mutants on cellulosic substrates.

Specific activities were determined for the wild-type protein and each of the mutants with Avicel, a model crystalline cellulose, and filter paper, as substrates. On Avicel, deletion of the individual CBMs led to a decrease in specific activity of the truncated mutant (TM1, TM2, and TM3) (Table 1). The truncated mutant with either two or one of the CBM3b (TM1 and TM2, respectively) only showed a slight decrease in specific activity compared to the WT enzyme. In contrast, deleting the two CBM3b's led to a protein with less than half the specific activity of the WT protein on Avicel. A similar trend was observed for the specific activity on filter paper as substrate, although the decreases in activity were less pronounced (Table 1). On both substrates, a construct made up of the GH9 catalytic module alone (TM4) had only 3.8 and 16.2% of the activities observed for the WT protein on Avicel and filter paper, respectively.

Table 1.

Specific activities and kinetic parameters of the CbCel9B/Man5A wild type, its truncation mutants, and TM3 mutants on cellulose substratesa

| Protein | Sp act (μmol of released sugar/min/μmol of enzyme) |

PASCb |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avicel | Filter paper | kcat (s−1) | Km (mg/ml) | kcat/Km (s−1 ml/mg) | |

| WT | 10.15 ± 0.51 | 16.12 ± 2.86 | 2.58 ± 0.15 | 0.36 ± 0.10 | 7.16 |

| TM1 | 8.53 ± 1.47 | 17.27 ± 2.06 | 2.12 ± 0.13 | 0.14 ± 0.07 | 15.14 |

| TM2 | 8.94 ± 0.89 | 14.31 ± 3.13 | 2.16 ± 0.18 | 0.19 ± 0.10 | 11.37 |

| TM3 | 4.47 ± 0.81 | 12.87 ± 1.44 | 3.09 ± 0.30 | 0.65 ± 0.24 | 4.75 |

| TM3G208WG | 3.68 ± 0.69 | 13.74 ± 1.80 | 7.92 ± 0.78 | 1.71 ± 0.45 | 4.63 |

| TM3G208W | 4.86 ± 0.49 | 14.61 ± 3.41 | 6.36 ± 0.74 | 1.35 ± 0.46 | 4.71 |

| TM3T298F | 5.53 ± 0.53 | 15.14 ± 1.71 | 8.53 ± 0.67 | 2.17 ± 0.42 | 3.93 |

| TM4 | 0.39 ± 0.02 | 2.62 ± 0.56 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 3.73 ± 0.81 | 0.02 |

The reactions were carried out at 75°C except that for TM4, which was performed at 45°C. Note that the substrate is complex in nature and the kinetic parameters are apparent values. Values are presented means ± the standard deviations where applicable.

PASC, phosphoric acid swollen cellulose.

The phosphoric acid swollen cellulose, derived from Avicel, was used to examine the kinetic parameters of the WT protein and its mutants (Table 1). The estimated kcat values for the WT (2.58 s−1) and its truncated mutants of TM1, TM2, and TM3 (2.12 to 3.09 s−1) were very modest. Interestingly, TM1 exhibited a catalytic efficiency that was twice higher than that of the wild type, suggesting that the catalytic activities of the GH9 and GH5 modules are functionally coupled, i.e., the activity of each GH catalytic module in the wild-type enzyme is modulated by the other catalytic module. Similar functional coupling of different catalytic modules within a single polypeptide was proposed for another plant cell wall-degrading enzyme, Prevotella ruminicola Xyn10D-Fae1A (13), a two-domain arginine kinase from the deep-sea clam Calyptogena kaikoi (53), and a flagellar creatine kinase from Chaetopterus variopedatus (22). The kinetic parameters of TM4, the protein with only the GH9 catalytic module were very poor compared to the proteins linked to the CBMs, alluding to the importance of these auxiliary modules to the function of CbCel9B/Man5A.

Activities and kinetic parameters of CbCel9B/Man5A and its mutants on mannan substrates.

The enzymatic activities of CbCel9B/Man5A and its mutants on mannan substrates were also investigated. The substrates tested were locust bean gum, guar gum, and konjac glucomannan. The wild-type enzyme exhibited very high apparent kcat on all tested mannose-based substrates. On locust bean gum, konjac glucomannan, and guar gum, the apparent kcat values were 1,420, 1,068, and 696 s−1, respectively (Table 2). Based on the data in Table 2, the catalytic activity for degradation of mannose-configured substrates is located in the GH5 module. It was observed that cleaving the GH9 module from the polypeptide to create the TM5 mutant increased the apparent kcat of this mutant, compared to the wild-type, by 2.4-, 2.8-, and 1.6-fold for locust bean gum, guar gum, and konjac glucomannan, respectively. This observation further supports our hypothesis that the two catalytic activities are coupled in the wild-type protein, and the cleavage of one catalytic module allows the other catalytic module to more freely hydrolyze its substrate. Note that the standard error was quite high for the apparent kcat for guar gum. A corresponding increase in the Km of TM5 on each mannose-configured substrate led to catalytic efficiencies that were lower than those determined for the wild-type protein (Table 2). The mutants without GH5 catalytic module were virtually devoid of activity on both locust bean gum and guar gum. These mutants, however, exhibited very high activity on konjac glucomannan.

Table 2.

Kinetic parameters of the CbCel9B/Man5A wild type, its truncation mutants, and TM3 mutants on mannan substrates and konjac glucomannana

| Protein | Locust bean gum |

Guar gum |

Konjac glucomannan |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kcat (s−1) | Km (mg/ml) | kcat/Km (s−1 ml/mg) | kcat (s−1) | Km (mg/ml) | kcat/Km (s−1 ml/mg) | kcat (s−1) | Km (mg/ml) | kcat/Km (s−1 ml/mg) | |

| WT | 1,420 ± 158 | 0.62 ± 0.27 | 2,290 | 696 ± 56.7 | 2.26 ± 0.42 | 308 | 1,068 ± 271 | 1.84 ± 1.03 | 581 |

| TM1 | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 3.89 ± 0.41 | 5.9 × 10−2 | ND | ND | ND | 907 ± 50.7 | 1.85 ± 0.30 | 490 |

| TM3 | 0.15 ± 0.06 | 4.36 ± 2.82 | 3.5 × 10−2 | (1.03 ± 0.17) × 10−2 | 0.94 ± 0.50 | 1.10 × 10−2 | 611 ± 68.9 | 1.30 ± 0.43 | 470 |

| TM3G208WG | 2.31 ± 0.15 | 1.93 ± 0.31 | 1.2 | 1.03 ± 0.35 | 9.28 ± 4.36 | 1.11 × 10−1 | 1,614 ± 143 | 2.37 ± 0.49 | 681 |

| TM3G208W | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 3.33 ± 1.49 | 3.7 × 10−2 | (1.01 ± 0.01) × 10−2 | 0.50 ± 0.20 | 2.01 × 10−2 | 1,119 ± 160 | 1.80 ± 0.68 | 621 |

| TM3T298F | 1.12 ± 0.55 | 12.58 ± 7.94 | 8.9 × 10−2 | (8.92 ± 1.98) × 10−2 | 3.62 ± 1.53 | 2.47 × 10−2 | 1,102 ± 77.4 | 2.61 ± 0.43 | 422 |

| TM5 | 3,446 ± 367 | 1.82 ± 0.48 | 1,893 | 1,940 ± 570 | 11.98 ± 4.69 | 162 | 1,710 ± 119 | 3.72 ± 0.48 | 460 |

Konjac glucomannan (Megazyme) is a polysaccharide with mixed linkage of glucose and mannose. Note that the substrate is complex in nature and the kinetic parameters are apparent values. Values are presented as means ± the standard deviations where applicable. ND, not determined.

Site-directed mutagenesis.

The architectural diversity of GH9 modules have been assigned to four different groups known as theme A, B, C, and D (29). In CbCel9B/Man5A, the GH9 catalytic module is linked to an accessory CBM3c at its C terminus, and this is the architecture of the members of theme B1. In theme B1, there are both processive endoglucanases (10, 19, 45) and nonprocessive endoglucanases (2, 17). The distribution of reducing ends in the soluble and insoluble fractions of cellulase-hydrolyzed filter paper is commonly used to estimate the processivity of a cellulase (27). Our results, based on such an experiment, determined that CbCel9B/Man5A and its truncation mutants (TM1, TM2, TM3, and TM4) do not harbor a processive GH9 catalytic module since their end products contained 40 to 50% insoluble reducing ends (see Table S2 in the supplemental material).

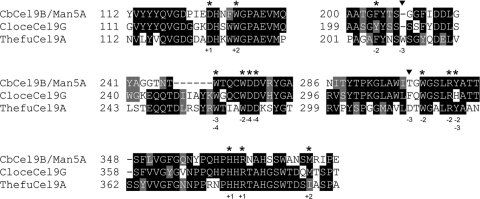

An amino acid sequence alignment of the GH9 domain of CbCel9B/Man5A with those of Clostridium cellulolyticum Cel9G (a nonprocessive endoglucanase) and Thermobifida fusca Cel9A (a processive endoglucanase) was examined. The C. cellulolyticum and T. fusca proteins represent two types of family 9 theme B1 endoglucanases with the enzyme–cello-oligosaccharides cocrystal structures solved (36, 45). The amino acid sequence alignment showed that most of the residues involved in cellulose substrate binding are well conserved in the GH9 module of CbCel9B/Man5A (Fig. 3). However, neither of two aromatic residues (Trp-209 in T. fusca and Phe-308 in C. cellulolyticum) responsible for hydrophobic stacking interaction at subsite −3 is present in CbCel9B/Man5A (Fig. 3). Since aromatic residues involved in hydrophobic stacking interactions with the substrates contribute to the processivity of the enzyme during hydrolysis of crystalline substrate (24, 63), we mutated the corresponding amino acid residue in CbCel9B/Man5ATM3 to an aromatic residue by changing Gly-208 to Trp-208 or by inserting a tryptophan before Gly-208 to obtain a TM3G208W and a TM3G208WG mutant, respectively. These mutants mimicked the T. fusca enzyme. In addition, T-298 was also changed to Phe-298 to obtain TM3T298F mutant, which mimicked the C. cellulolyticum enzyme.

Fig 3.

Amino acid sequence alignment of the GH9 domain of CbCel9B/Man5A with those of CloceCel9G (Clostridium cellulolyticum Cel9G, GenBank accession number AAA73868) (36) and ThefuCel9A (Thermobifida fusca Cel9A, GenBank accession number AAB42155) (45). CloceCel9G (nonprocessive) and ThefuCel9A (processive) represent the two types of family 9 theme B1 endoglucanases whose enzyme–cello-oligosaccharide complex structures have been solved. The asterisks indicate the identical or similar amino acid residues within the three sequences. The filled triangles indicate nonconserved residues. The numbers under a specific amino acid residue indicate the subsites of the cello-oligosaccharides interacting with this amino acid residue based on the CloceCel9G and ThefuCel9A enzyme-substrate complex structures.

The secondary structures of the three mutants did not show any gross differences compared to CbCel9B/Man5ATM3 as revealed by circular dichroism (CD) scans (see Table S3 in the supplemental material), suggesting that the mutations did not result in gross changes in the secondary structural elements of the proteins compared to CbCel9B/Man5ATM3. Compared to the parental protein (TM3), the specific activities of the three mutants on Avicel and filter paper were not different (Table 1). The mutations also did not aid us in modifying TM3 into a processive endoglucanase, as the ratio of soluble versus insoluble reducing ends remained unchanged (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The apparent kcat values of the mutants with PASC as the substrate increased by ∼2-fold. However, the Km values also increased, leading to catalytic efficiencies (kcat/Km) that were similar to that of CbCel9B/Man5ATM3 (Table 1).

Unexpectedly, the apparent kcat values of TM3G208WG with locust bean gum and guar gum, as substrates, were increased 15- and 100-fold compared to the values determined for TM3 (Table 2). Moreover, the catalytic efficiencies of this mutant for locust bean gum and guar gum also increased by 34- and 10-fold, respectively (Table 2). The site-directed mutagenesis of the TM3 truncated mutant also increased its apparent kcat on konjac glucomannan by 2-fold or higher (Table 2).

Binding of CbCel9B/Man5A to insoluble cellulose substrates.

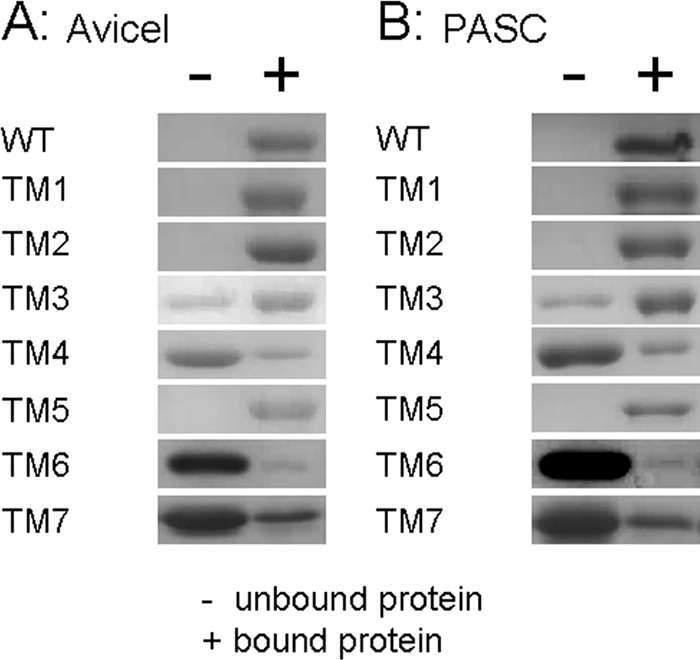

The CbCel9B/Man5A wild type, TM1, and TM5, which harbored all three CBMs (one CBM3c and two CBM3b) bound tightly to Avicel (Fig. 4A) and PASC (Fig. 4B). The truncated mutant TM2, which harbored the CBM3c and one CBM3b, also bound tightly to the two cellulosic substrates. The binding of TM3, which was composed of the GH9 module and the CBM3c, to the insoluble cellulose was weaker than those for wild-type, TM1, TM2, and TM5 (Fig. 4). Depletion binding isotherms were used to estimate the dissociation constant and maximal binding capacity of TM3 to Avicel as 0.52 ± 0.20 μM and 423.9 ± 50.7 nmol of protein/g of Avicel, respectively. The two components of TM3, i.e., the GH9 module (TM4) and CBM3c (TM6), were observed to weakly bind to insoluble cellulose (Fig. 4A and B). The binding of the CBM3c of CbCel9AMan5B (TM6) to insoluble cellulose was unexpected since this binding was not observed for other CBM3c characterized by the same method (10, 17, 19, 26). Note, however, that the bindings were weak and thus preventing us from obtaining the binding constants of the GH9 and CBM3c modules for Avicel. The CBM3b (TM7) also bound to Avicel and PASC (Fig. 4), although in this case also the binding constants could not be determined.

Fig 4.

Qualitative binding of the CbCel9B/Man5A wild type and its truncation mutants to Avicel (A) and phosphoric acid swollen cellulose (PASC) (B). Portions (30 μg) of each protein were incubated with 40 mg of Avicel cellulose/ml or 2.5 mg of PASC/ml in 50 mM Tris buffer–150 mM NaCl (pH 7.5). The mixture was shaken end over end at 4°C for 1 h. Then the bound and unbound proteins were separated by centrifugation of the mixture at 25,000 × g for 3 min. The cellulose pellet was washed four times with 1 ml of buffer (50 mM Tris buffer, 150 mM NaCl [pH 7.5]). The pellet was then added with 70 μl of 1× SDS-PAGE loading buffer and boiled for 5 min. The protein corresponding to a one-tenth volume of each fraction was subjected to SDS–12% PAGE.

DISCUSSION

Caldicellulosiruptor bescii is one of the few thermophilic bacteria reported to degrade crystalline cellulose (4, 59). It is of interest, therefore, to understand the strategy and the enzymes used by this bacterium for this purpose, as the knowledge could be of industrial importance. The enzyme studied in the present report is one of the most highly secreted proteins during growth of C. bescii on cellulosic substrates (35). Thus, understanding how CbCel9B/Man5A, a polypeptide encoded in related species, functions should provide insight into how members of the Caldicellulosiruptor deconstruct plant cell wall.

CbCel9B/Man5A is the first GH9 cellulase characterized in detail with two tandem CBM3b modules linked to the GH9-CBM3c domains. The CBM3b module (TM7) binds to insoluble cellulose (Fig. 4). Deletion of one CBM3b (TM2) from TM1 did not significantly affect the binding to these substrates (Fig. 4). Correspondingly, the specific activities and kinetic parameters of TM1 and TM2 are similar for cellulose substrates (Table 1). Deletion of both CBM3b's (TM3) reduced both the binding to the insoluble substrates and the specific activities for Avicel and filter paper (Table 1). Therefore, the CBM3b modules facilitate the deconstruction of crystalline cellulose by CbCel9B/Man5A.

CbCel9B/Man5A and its truncation mutants, especially TM3, retained considerable activities after incubation at 75°C for 24 h. For other hyperthermophilic endoglucanases, Cel5A of Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis has >80% residual activity after incubation at 60°C for 24 h (34), the Avicelase I of Clostridium stercorarium has >60% residual activity after incubation at 80°C for 12 h (7), and the CelB of Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus has a half-life of 29 h at 70°C (46), CelA of C. bescii has a half-life at 85°C of >4 h (65), EglA of Pyrococcus furious has a half-life of 40 h at 94°C (3), EGPh of Pyrococcus horikoshii has a residual activity of 80% after incubation at 97°C for 3 h (1), and CelB of Thermotoga neapolitana has a residual activity of 73% after incubation at 100°C for 4 h (5). CbCel9B/Man5A wild-type has a half-life of about 22 h at 75°C (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), which is similar to CelB of C. saccharolyticus. The thermostability property of the multifunctional enzyme can facilitate recycling during its use in releasing fermentable sugars from cellulosic substrates at high temperatures. Introduction of an enzyme recycling step in cellulosic ethanol production can significantly reduce the cost of production of the value added product.

The C. bescii CelA (ORF1954, GenBank accession number ACM60955) is the first cellulase characterized from this bacterium (65). It is the most highly secreted cellulase (ca. 40%), while CbCel9B/Man5A is the second most highly secreted protein (ca. 17%) when C. bescii is grown on Avicel medium (35). Similar but not identical to CbCel9B/Man5A, CelA is composed of an N-terminally located GH9 module, a C-terminally located GH48 module, and three CBM3 modules between the two catalytic domains. The specific activity of CbCel9B/Man5A on Avicel (10.15 μmol of sugar/min/μmol of enzyme) was much lower than that of the full-length CelA (55.0 μmol of sugar/min/μmol of enzyme) but only slightly lower than that of its truncation mutant CelA′ containing the GH9 catalytic module and the CBMs (18.0 μmol of sugar/min/μmol of enzyme) (65). In comparison to other hyperthermostable endoglucanases, this specific activity of CbCel9B/Man5A on Avicel is lower than those of Cel5A (composed of an N-terminal GH5 catalytic module and a C-terminal CBM17/28 module) of T. tengcongensis (60.0 μmol of sugar/min/μmol of enzyme) (34) and Avicelase I (composed of an N-terminal GH9 catalytic module, a CBM3, two domains of unknown function [DUF], and a C-terminal CBM3) of C. stercorarium (30.2 μmol of sugar/min/μmol of enzyme) (7). The parameter is, however, comparable to that of EGPh (composed of a GH5 catalytic module) of P. horikoshii (12.7 μmol of sugar/min/μmol of enzyme) (1), but much higher than that of the C. saccharolyticus CelB (composed of an N-terminal GH10 catalytic module, a CBM3, and a C-terminal GH5 module) (0.4 μmol of sugar/min/μmol of enzyme) (54). The specific activity of CbCel9B/Man5A on filter paper was comparable to those of CelB of T. neapolitana (composed of a GH12 catalytic module) (20.8 μmol of sugar/min/μmol of enzyme) (5), Cel5A of T. tengcongensis (18.5 μmol of sugar/min/μmol of enzyme) (34), and EglA of P. furious (composed of a GH12 catalytic module) (18.7 μmol of sugar/min/μmol of enzyme) (3) but much higher than those of CelA of T. neapolitana (composed of a GH12 catalytic module) (3.2 μmol of sugar/min/μmol of enzyme) (5) and CelB of C. saccharolyticus (1.8 μmol of sugar/min/μmol of enzyme) (54). Note that the assay conditions (reaction temperature, buffer, reaction period, method for measuring reducing sugar, and lab equipment) used for these specific activities likely vary among the enzymes described above. Nevertheless, CbCel9B/Man5A appears to be a promising enzyme for releasing fermentable sugars from cellulosic substrates at high temperatures.

Interestingly, seven of the nine genes in the gene cluster in which the CbCel9B/Man5A encoding gene is located also contain CBM3b modules that are identical or highly similar (identity > 98%) to the CBM3b of CbCel9B/Man5A. Six of the polypeptides in the gene cluster have either two or three tandem CBM3b repeats. It is reasonable to postulate that these CBM3b modules aid in plant cell wall hydrolysis. One physiological implication for the plurality of the CBM3b module in the various proteins is that they allow C. bescii cellulases and hemicellulases to congregate on plant cell wall to orchestrate synergistic release of fermentable sugars for metabolism.

The mannanase activity of CbCel9B/Man5A was mainly located in the GH5 module; however, limited mannanase activity was also observed with the construct containing the GH9 domain as the catalytic module. In most cases, family 9 glycoside hydrolases are described as endoglucanase, cellobiohydrolase, 1,4-β-d-glucan glucohydrolase, β-glucosidase, and exo-β-glucosaminidase. The Bacillus licheniformis Cel9 is the only member of this family reported to have mannanase activity (55); however, its kinetic data and hydrolysis pattern on mannose-configured substrates are unknown. The TM1 mutant of CbCel9B/Man5A showed different hydrolysis patterns compared to the TM5 mutant, in that the GH9 catalytic module in TM1 needed a minimal chain length of five and released mannobiose as the shortest end product, while the GH5 catalytic module in TM5 needed a minimal chain length of three and released mannose as the shortest end product. The ability of the GH9 module of CbCel9B/Man5A to hydrolyze mannose-configured substrates suggests that the catalytic module can both accommodate the equatorial C-2 hydroxyl of glucose and also tolerate the axial C-2 hydroxyl of mannose.

The absence of a tryptophan for −3 subsite hydrophobic interaction was proposed to destabilize the nonproductive binding which might impair the processivity of a GH9 cellulase (41). The mutations of G208 and T298 into aromatic residues (TM3G208WG, TM3G208W, and TM3T298F), however, did not change the processivity of TM3, as reflected by the unaltered ratios of soluble versus insoluble reducing ends. The specific activities of the mutants on crystalline cellulose (Avicel and filter paper) were also comparable to that of the parental TM3. However, for noncrystalline PASC, all turnover numbers of the mutants were increased by ∼2-fold, while the catalytic efficiencies remained unchanged. The different structures of crystalline and noncrystalline cellulose might affect the performance of these enzymes. One of the mutants, TM3G208WG, increased its substrate specificity for locust bean gum by 35-fold (TM3, [kcat/Km]LBG/[kcat/Km]PASC = 7.4 × 10−3; TM3G208WG, [kcat/Km]LBG/[kcat/Km]PASC = 0.25), suggesting that residues for subsite −3 interaction might be involved in substrate selection.

CBM3c was proposed to bind loosely to the cellulose ligand and feed a cellulose chain into the GH9 catalytic module (45). However, no biochemical data were provided for this binding. In the cocrystal structure of family 9 cellulase in complex with cello-oligosaccharides, the binding of the cello-oligosaccharide to CBM3c has not been observed thus far (36, 45). Our results suggest that a CBM3c can indeed bind to insoluble cellulose although the binding appeared weak. A sequence alignment of CbCel9B/Man5A with its homologs revealed that considerable differences exist in the amino acid residues proposed to interact with the ligand (29, 32, 33) between CbCel9B/Man5A CBM3c with its homologues. Notably, the Q553, R557, E559, and R563 residues in ThefuCel9A, proposed to interact with the ligand, are replaced by E545, K549, Q561, and K565, respectively, in the CBM3c of CbCel9B/Man5A (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). This observation may be akin to the fine-tuning demonstrated in a Caldanaerobius polysaccharolyticus family 16 CBM by mutating one polar residue (Q121 to E121) involved in hydrogen bonding with the ligand (47). The E545, K549, Q561, and K565 residues can also be found in four CBM3 modules from the related organisms C. kronotskyensis, C. saccharolyticus, C. obsidiansis, and Caldicellulosiruptor sp. strain Tok7B.1 (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). A three-dimensional structure of a CBM3c in complex with a ligand is still lacking, which hinders accurate designation of residues important for ligand binding. Due to the diversity of CBM3c modules (29), one may postulate that there are variants of CBM3c that are capable of holding a cello-oligosaccharide tightly enough to capture this complex in a crystal.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Energy Biosciences Institute for supporting our research on lignocellulose depolymerization.

We thank Michael Iakiviak, Libin Ye, Young Hwan Moon, Jing Zhang, and Shosuke Yoshida of the Energy Biosciences Institute for scientific discussions.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 13 January 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ando S, Ishida H, Kosugi Y, Ishikawa K. 2002. Hyperthermostable endoglucanase from Pyrococcus horikoshii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:430–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arai T, et al. 2001. Sequence of celQ and properties of CelQ, a component of the Clostridium thermocellum cellulosome. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 57:660–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bauer MW, et al. 1999. An endoglucanase, EglA, from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus hydrolyzes β-1,4 bonds in mixed-linkage (1→3),(1→4)-β-d-glucans and cellulose. J. Bacteriol. 181:284–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Blumer-Schuette SE, Lewis DL, Kelly RM. 2010. Phylogenetic, microbiological, and glycoside hydrolase diversities within the extremely thermophilic, plant biomass-degrading genus Caldicellulosiruptor. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:8084–8092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bok JD, Yernool DA, Eveleigh DE. 1998. Purification, characterization, and molecular analysis of thermostable cellulases CelA and CelB from Thermotoga neapolitana. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:4774–4781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bourgault R, Oakley AJ, Bewley JD, Wilce MC. 2005. Three-dimensional structure of (1,4)-β-d-mannan mannanohydrolase from tomato fruit. Protein Sci. 14:1233–1241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bronnenmeier K, Staudenbauer WL. 1990. Cellulose hydrolysis by a highly thermostable endo-l,4-β-glucanase (Avicelase I) from Clostridium stercorarium. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 12:431–436 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cai S, Zheng X, Dong X. 2011. CBM3d, a novel subfamily of family 3 carbohydrate-binding modules identified in Cel48A exoglucanase of Cellulosilyticum ruminicola. J. Bacteriol. 193:5199–5206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Caines ME, et al. 2007. Structural and mechanistic analyses of endo-glycoceramidase II, a membrane-associated family 5 glycosidase in the Apo and GM3 ganglioside-bound forms. J. Biol. Chem. 282:14300–14308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chiriac AI, et al. 2010. Engineering a family 9 processive endoglucanase from Paenibacillus barcinonensis displaying a novel architecture. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 86:1125–1134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cutfield SM, et al. 1999. The structure of the exo-β-(1,3)-glucanase from Candida albicans in native and bound forms: relationship between a pocket and groove in family 5 glycosyl hydrolases. J. Mol. Biol. 294:771–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dam P, et al. 2011. Insights into plant biomass conversion from the genome of the anaerobic thermophilic bacterium Caldicellulosiruptor bescii DSM 6725. Nucleic Acids Res. 39:3240–3254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dodd D, et al. 2009. Biochemical analysis of a β-d-xylosidase and a bifunctional xylanase-ferulic acid esterase from a xylanolytic gene cluster in Prevotella ruminicola 23. J. Bacteriol. 191:3328–3338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dodd D, Moon YH, Swaminathan K, Mackie RI, Cann IK. 2010. Transcriptomic analyses of xylan degradation by Prevotella bryantii and insights into energy acquisition by xylanolytic Bacteroidetes. J. Biol. Chem. 285:30261–30273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Eckert K, Vigouroux A, Lo Leggio L, Morera S. 2009. Crystal structures of A. acidocaldarius endoglucanase Cel9A in complex with cello-oligosaccharides: strong −1 and −2 subsites mimic cellobiohydrolase activity. J. Mol. Biol. 394:61–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fukumori F, Kudo T, Narahashi Y, Horikoshi K. 1986. Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequence of the alkaline cellulase gene from the alkalophilic Bacillus sp. strain 1139. J. Gen. Microbiol. 132:2329–2335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gal L, et al. 1997. CelG from Clostridium cellulolyticum: a multidomain endoglucanase acting efficiently on crystalline cellulose. J. Bacteriol. 179:6595–6601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gibbs MD, et al. 2000. Multidomain and multifunctional glycosyl hydrolases from the extreme thermophile Caldicellulosiruptor isolate Tok7B. 1. Curr. Microbiol. 40:333–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gilad R, et al. 2003. CelI, a noncellulosomal family 9 enzyme from Clostridium thermocellum, is a processive endoglucanase that degrades crystalline cellulose. J. Bacteriol. 185:391–398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Han Y, et al. 2010. Comparative analyses of two thermophilic enzymes exhibiting both β-1,4 mannosidic and β-1,4 glucosidic cleavage activities from Caldanaerobius polysaccharolyticus. J. Bacteriol. 192:4111–4121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hilge M, et al. 1998. High-resolution native and complex structures of thermostable β-mannanase from Thermomonospora fusca: substrate specificity in glycosyl hydrolase family 5. Structure 6:1433–1444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hoffman GG, Davulcu O, Sona S, Ellington WR. 2008. Contributions to catalysis and potential interactions of the three catalytic domains in a contiguous trimeric creatine kinase. FEBS J. 275:646–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Honda Y, Shimaya N, Ishisaki K, Ebihara M, Taniguchi H. 2011. Elucidation of exo-β-d-glucosaminidase activity of a family 9 glycoside hydrolase (PBPRA0520) from Photobacterium profundum SS9. Glycobiology 21:503–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Horn SJ, et al. 2006. Costs and benefits of processivity in enzymatic degradation of recalcitrant polysaccharides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:18089–18094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Iakiviak M, Mackie RI, Cann IK. 2011. Functional analyses of multiple lichenin-degrading enzymes from the rumen bacterium Ruminococcus albus 8. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:7541–7550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Irwin D, et al. 1998. Roles of the catalytic domain and two cellulose binding domains of Thermomonospora fusca E4 in cellulose hydrolysis. J. Bacteriol. 180:1709–1714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Irwin DC, Spezio M, Walker LP, Wilson DB. 1993. Activity studies of eight purified cellulases: specificity, synergism, and binding domain effects. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 42:1002–1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jauris S, et al. 1990. Sequence analysis of the Clostridium stercorarium celZ gene encoding a thermoactive cellulase (Avicelase I): identification of catalytic and cellulose-binding domains. Mol. Gen. Genet. 223:258–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jindou S, et al. 2006. Novel architecture of family-9 glycoside hydrolases identified in cellulosomal enzymes of Acetivibrio cellulolyticus and Clostridium thermocellum. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 254:308–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kataeva IA, et al. 2009. Genome sequence of the anaerobic, thermophilic, and cellulolytic bacterium “Anaerocellum thermophilum” DSM 6725. J. Bacteriol. 191:3760–3761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lever M. 1972. A new reaction for colorimetric determination of carbohydrates. Anal. Biochem. 47:273–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li Y, Irwin DC, Wilson DB. 2010. Increased crystalline cellulose activity via combinations of amino acid changes in the family 9 catalytic domain and family 3c cellulose binding module of Thermobifida fusca Cel9A. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:2582–2588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Li Y, Irwin DC, Wilson DB. 2007. Processivity, substrate binding, and mechanism of cellulose hydrolysis by Thermobifida fusca Cel9A. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:3165–3172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liang C, et al. 2011. Cloning and characterization of a thermostable and halo-tolerant endoglucanase from Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis MB4. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 89:315–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lochner A, et al. 2011. Use of label-free quantitative proteomics to distinguish the secreted cellulolytic systems of Caldicellulosiruptor bescii and Caldicellulosiruptor obsidiansis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:4042–4054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mandelman D, et al. 2003. X-ray crystal structure of the multidomain endoglucanase Cel9G from Clostridium cellulolyticum complexed with natural and synthetic cello-oligosaccharides. J. Bacteriol. 185:4127–4135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Meinke A, et al. 1991. Unusual sequence organization in CenB, an inverting endoglucanase from Cellulomonas fimi. J. Bacteriol. 173:308–314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mejia-Castillo T, Hidalgo-Lara ME, Brieba LG, Ortega-Lopez J. 2008. Purification, characterization and modular organization of a cellulose-binding protein, CBP105, a processive β-1,4-endoglucanase from Cellulomonas flavigena. Biotechnol. Lett. 30:681–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Moon YH, Iakiviak M, Bauer S, Mackie RI, Cann IK. 2011. Biochemical analyses of multiple endoxylanases from the rumen bacterium Ruminococcus albus 8 and their synergistic activities with accessory hemicellulose degrading enzymes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:5157–5169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Park JK, Wang LX, Patel HV, Roseman S. 2002. Molecular cloning and characterization of a unique β-glucosidase from Vibrio cholerae. J. Biol. Chem. 277:29555–29560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Parsiegla G, Belaich A, Belaich JP, Haser R. 2002. Crystal structure of the cellulase Cel9M enlightens structure/function relationships of the variable catalytic modules in glycoside hydrolases. Biochemistry 41:11134–11142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pastor FI, et al. 2001. Molecular cloning and characterization of a multidomain endoglucanase from Paenibacillus sp. BP-23: evaluation of its performance in pulp refining. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 55:61–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Qi M, Jun HS, Forsberg CW. 2008. Cel9D, an atypical 1,4-β-d-glucan glucohydrolase from Fibrobacter succinogenes: characteristics, catalytic residues, and synergistic interactions with other cellulases. J. Bacteriol. 190:1976–1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sakamoto T, Taniguchi Y, Suzuki S, Ihara H, Kawasaki H. 2007. Characterization of Fusarium oxysporum β-1,6-galactanase, an enzyme that hydrolyzes larch wood arabinogalactan. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:3109–3112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sakon J, Irwin D, Wilson DB, Karplus PA. 1997. Structure and mechanism of endo/exocellulase E4 from Thermomonospora fusca. Nat. Struct. Biol. 4:810–818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Saul DJ, et al. 1990. celB, a gene coding for a bifunctional cellulase from the extreme thermophile “Caldocellum saccharolyticum.” Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:3117–3124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Su X, et al. 2010. Mutational insights into the roles of amino acid residues in ligand binding for two closely related family 16 carbohydrate binding modules. J. Biol. Chem. 285:34665–34676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tailford LE, et al. 2009. Understanding how diverse β-mannanases recognize heterogeneous substrates. Biochemistry 48:7009–7018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tamaru Y, Karita S, Ibrahim A, Chan H, Doi RH. 2000. A large gene cluster for the Clostridium cellulovorans cellulosome. J. Bacteriol. 182:5906–5910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tanabe T, Morinaga K, Fukamizo T, Mitsutomi M. 2003. Novel chitosanase from Streptomyces griseus HUT 6037 with transglycosylation activity. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 67:354–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tolonen AC, Chilaka AC, Church GM. 2009. Targeted gene inactivation in Clostridium phytofermentans shows that cellulose degradation requires the family 9 hydrolase Cphy3367. Mol. Microbiol. 74:1300–1313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tormo J, et al. 1996. Crystal structure of a bacterial family-III cellulose-binding domain: a general mechanism for attachment to cellulose. EMBO J. 15:5739–5751 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Uda K, et al. 2008. Two-domain arginine kinase from the deep-sea clam Calyptogena kaikoi: evidence of two active domains. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 151:176–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. VanFossen AL, Ozdemir I, Zelin SL, Kelly RM. 2011. Glycoside hydrolase inventory drives plant polysaccharide deconstruction by the extremely thermophilic bacterium Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 108:1559–1569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Vlasenko E, Schulein M, Cherry J, Xu F. Substrate specificity of family 5, 6, 7, 9, 12, and 45 endoglucanases. Bioresour. Technol. 101:2405–2411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Whitmore L, Wallace BA. 2004. DICHROWEB, an online server for protein secondary structure analyses from circular dichroism spectroscopic data. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:W668–W673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Whitmore L, Wallace BA. 2008. Protein secondary structure analyses from circular dichroism spectroscopy: methods and reference databases. Biopolymers 89:392–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yang SJ, et al. 2010. Classification of “Anaerocellum thermophilum” strain DSM 6725 as Caldicellulosiruptor bescii sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 60:2011–2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Yang SJ, et al. 2009. Efficient degradation of lignocellulosic plant biomass, without pretreatment, by the thermophilic anaerobe “Anaerocellum thermophilum” DSM 6725. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:4762–4769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Yeoman CJ, et al. 2010. Thermostable enzymes as biocatalysts in the biofuel industry. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 70:1–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Yoshida S, et al. 2011. Structural and functional analyses of a glycoside hydrolase family 5 enzyme with an unexpected β-fucosidase activity. Biochemistry 50:3369–3375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Yoshida S, Mackie RI, Cann IK. 2010. Biochemical and domain analyses of FSUAxe6B, a modular acetyl xylan esterase, identify a unique carbohydrate binding module in Fibrobacter succinogenes S85. J. Bacteriol. 192:483–493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Zakariassen H, et al. 2009. Aromatic residues in the catalytic center of chitinase A from Serratia marcescens affect processivity, enzyme activity, and biomass converting efficiency. J. Biol. Chem. 284:10610–10617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zhang XZ, Sathitsuksanoh N, Zhang YH. 2010. Glycoside hydrolase family 9 processive endoglucanase from Clostridium phytofermentans: heterologous expression, characterization, and synergy with family 48 cellobiohydrolase. Bioresour. Technol. 101:5534–5538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zverlov V, Mahr S, Riedel K, Bronnenmeier K. 1998. Properties and gene structure of a bifunctional cellulolytic enzyme (CelA) from the extreme thermophile “Anaerocellum thermophilum” with separate glycosyl hydrolase family 9 and 48 catalytic domains. Microbiology 144(Pt 2):457–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Zverlov VV, Velikodvorskaya GA, Schwarz WH. 2003. Two new cellulosome components encoded downstream of celI in the genome of Clostridium thermocellum: the non-processive endoglucanase CelN and the possibly structural protein CseP. Microbiology 149:515–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.