Abstract

Germination was evaluated as an enhancement to decontamination methods for removing Bacillus spores from drinking water infrastructure. Germinating spores before chlorinating cement mortar or flushing corroded iron was more effective than chlorinating or flushing alone.

TEXT

Bacillus spores are resistant to disinfection and other inactivation methods compared to vegetative bacteria (16, 18, 19, 28). Spores can be used as a benchmark for decontamination of biological agents, including biothreat agents such as Bacillus anthracis, from drinking water infrastructures. Bacillus spores are persistent on common drinking water infrastructure surfaces like corroded iron (4, 10, 23, 24) and cement mortar (21, 26) in the absence and presence of disinfectants. Germination has been studied as a decontamination method for Bacillus spores on home plumbing materials (PVC and copper) using l-alanine and inosine (13). This study examines the effectiveness of germinating Bacillus globigii spores attached to corroded iron and cement-mortar coupons with tryptic soy broth (TSB) and decontaminating with flushing and chlorination in a pilot-scale drinking water system. Optimal germination conditions were determined with bench-scale experiments using pH and temperature relevant to drinking water systems.

Bacillus atrophaeus subsp. globigii acted as a surrogate for pathogenic B. anthracis since it is more resistant to free chlorine (22). B. atrophaeus subsp. globigii spore preparation is detailed elsewhere (24). Purified spores were reintroduced into generic spore medium and cultured for 5 days at 35.5°C. The resulting spore suspension was used.

B. atrophaeus subsp. globigii spore germination was assessed by various germinant concentrations (10, 30, 50, and 100% TSB), pH values (6.3, 7.3, 8.3, and 9.0), and temperatures (5, 15, 20, and 25°C). Germination occurred in 15-ml tubes with 10 ml of a 108-CFU/ml spore suspension shaken at 170 rpm. Germination was measured using culture by heat shocking at 80°C for 10 min before spread plating on tryptic soy agar (TSA) and incubating for 24 ± 2 h at 35.5°C. All samples were plated in duplicate.

The drinking water distribution system simulator (DSS) has been described previously (26). Thirty 6.5-cm2 coupons were inserted flush with the pipe inner surface. Half were iron cut from a drinking water main and half were cement mortar made using American Water Works Association (AWWA) standard C104/A21.4-08 (2). Coupons were conditioned in the DSS for 1 month prior to contamination. Spore injection achieved 1 × 106 CFU/ml in the bulk phase for 2 h. The DSS was chlorinated for 22 h (5 and 25 mg/liter) and then flushed for 16 h. When applicable, a 2-h germination period occurred before chlorination. Coupons were sampled and analyzed as previously described (24). Coupon surfaces were sampled before injection to ensure that no spores were present.

Free chlorine was measured using standard method 4500-CI G (8). Laboratory germination experiments and pilot-scale decontamination experiments were performed in duplicate. Data points in the figures represent the averages of two independent experiments, and bars represent the range between the two experiments.

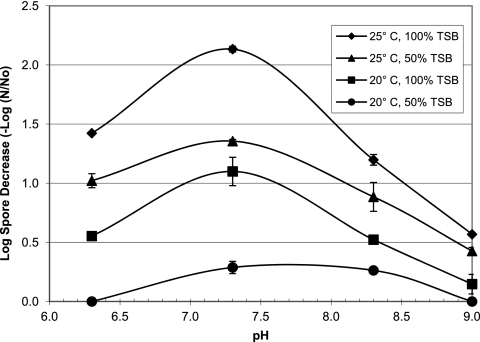

Figure 1 shows bench-scale spore germination results for pH and temperatures representative of drinking water distribution systems. Germination was minimal or not observed at concentrations below 50% and temperatures below 20°C (data not shown), which agrees with previous studies (3, 6, 11, 12, 15, 25, 27). Optimum germination conditions were 100% TSB, 25°C, and pH 7.3. pH 7.3 facilitated the most germination at all broth concentrations and temperatures. However, 25°C and 50% TSB produced more germination than 20°C and 100% TSB. Based on these results, pilot-scale germination was carried out at 25°C, pH 7.3, and 50% TSB. One hundred percent TSB would increase germination, but filling the DSS with TSB was not viable.

Fig 1.

Log decrease of heat-resistant spores after 2 h of contact with various germinant concentrations at pH values and temperatures representative of drinking water systems. Bars are the ranges between data points from duplicate experiments.

These results show that temperature is important to consider if germination was undertaken in a drinking water distribution system. Drinking water temperature falls below 10°C during winter in cold regions. Also, since free chlorine is less effective at colder temperatures (17–19), spore decontamination using germinant and free chlorine would be challenging at low temperatures. Germination was conducted with TSB since it is inexpensive and readily available in large quantities. TSB was an effective germinant for B. atrophaeus subsp. globigii, but germinant effectiveness is Bacillus species and strain specific (9, 14, 25). Research into inexpensive and readily available germinants for virulent B. anthracis is needed.

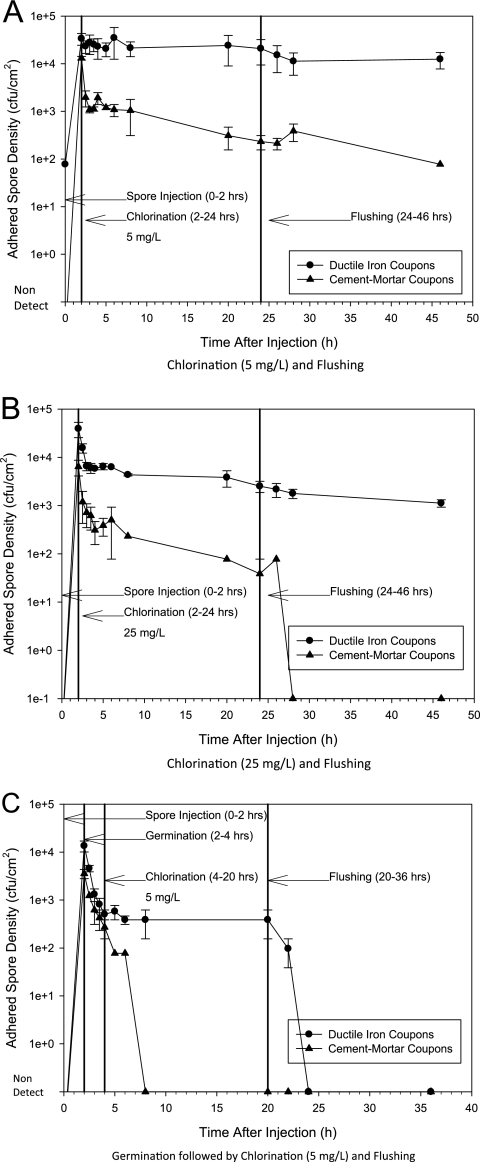

Figure 2 shows that germination before chlorination or flushing was more effective at removing adhered spores than chlorination or flushing alone. Chlorination followed by flushing is the only decontamination method shown in Fig. 2A and B. In Fig. 2A, 5 mg/liter free chlorine was ineffective at removing spores from iron. A 0.8-log spore decrease from iron was observed after dosing free chlorine at 25 mg/liter (Fig. 2B), but little decrease was observed thereafter. Free chlorine readily reacts with biofilm or oxidizes reduced iron species present on the coupons (5, 20). Free chlorine likely did not reach some spores residing in recesses of the corrosion matrix, which led to their persistence. Spores adhered to cement mortar were more susceptible to chlorination, and 25 mg/liter free chlorine with subsequent flushing reduced the number of spores to undetectable levels (Fig. 2C). Cement mortar is smoother than iron, which aids disinfectant transport. However, cement mortar can degrade free chlorine, which may explain the spore persistence at 5 mg/liter (1, 7).

Fig 2.

B. atrophaeus subsp. globigii spore persistence during germination, chlorination, and flushing in the pilot-scale DSS. The stages of the experiment are as follows: spore injection and contamination (hours 0 to 2 in all panels), germination (C only), disinfection (5 or 25 mg/liter), and flushing. Bars are the ranges between data points from duplicate experiments.

Figure 2C shows that germination resulted in 1.4- and 1.1-log spore decreases on iron and cement mortar, respectively. Spores were undetectable on the cement-mortar surface at 4 h after the 5-mg/liter chlorination stage began. Free chlorine had no effect on the number of spores adhered to iron after germination, but spores were not detected 4 h after the start of flushing. We speculate that germination was able to remove enough adhered spores that free chlorine (on cement mortar) and flushing (on iron) were able to decrease the remaining numbers to undetectable levels. Germinant (TSB) transport into the coupon is not hindered by reactions with coupon material or biofilm, which may allow it to germinate spores unreachable by free chlorine. Germinated vegetative cells may have detached during flushing or were inactivated by a low, mass-transfer-limited disinfectant residual that was ineffective against spores. Germinant-assisted chlorination or flushing may be a useful decontamination technique in water systems contaminated with spores, particularly in areas with old unlined iron pipes or where maintaining a disinfectant residual is difficult. Ultimately, efficacy and cost of disseminating a germinant over a sufficient area of the distribution system will dictate its use.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Noreen Adcock (USEPA) for preparing the B. atrophaeus subsp. globigii spores. We also thank John Wright (U.S. Army) for providing us with the B. atrophaeus subsp. globigii spores.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 20 January 2012

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-Jasser AO. 2007. Chlorine decay in drinking-water transmission and distribution systems: pipe service age effect. Water Res. 41:387–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.AWWA 2008. Standard for cement-mortar lining for ductile-iron pipe and fittings, AWWA C104/A21. 4-08. American Water Works Association, Denver, CO [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barlass PJ, Houston CW, Clements MO, Moir A. 2002. Germination of Bacillus cereus spores in response to l-alanine and to inosine: the roles of gerL and gerQ operons. Microbiology 148:2089–2095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calomiris JJ. 2006. Bacillus anthracis spores in a model drinking water pipe system. ASM Biodefense and Emerging Diseases Research Meeting. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen X, Stewart PS. 1996. Chlorine penetration into artificial biofilm is limited by a reaction and diffusion interaction. Environ. Sci. Technol. 30:2078–2083 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clements MO, Moir A. 1998. Role of the gerI operon of Bacillus cereus 569 in the response of spores to germinants. J. Bacteriol. 180:6729–6735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Digiano FA, Zhang W. 2005. Pipe section reactor to evaluate chlorine-wall reaction. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 97:74–85 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eaton AD, Clesceri LS, Rice EW, Greenberg AE. (ed). 2005. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater, 21st ed American Public Health Association, American Water Works Association, Water Environment Federation, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giebel JD, Carr KA, Anderson EC, Hanna PC. 2009. The germination-specific lytic enzymes SleB, CwlJ1, and CwlJ2 each contribute to Bacillus anthracis spore germination and virulence. J. Bacteriol. 191:5569–5576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hosni AA, Szabo JG, Bishop PL. 2011. The efficacy of chlorine dioxide as a disinfectant for Bacillus spores in drinking water biofilms. J. Environ. Eng. 137:569–574 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hyatt MT, Levinson HS. 1962. Conditions affecting Bacillus megaterium spore germination in glucose or various nitrogenous compounds. J. Bacteriol. 83:1231–1237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCormick NG. 1965. Kinetics of spore germination. J. Bacteriol. 89:1180–1185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morrow JB, Almeida JL, Fitzgerald LA, Cole KD. 2008. Association and decontamination of Bacillus spores in a simulated drinking water system. Water Res. 42:5011–5021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nicholson WL, Setlow P. 1990. Sporulation, germination and outgrowth, p 391–429. In Harwood CR, Cutting SM. (ed), Molecular biological methods for Bacillus. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Connor RJ, Halvorson HO. 1961. l-Alanine dehydrogenase: a mechanism controlling the specificity of amino acid-induced germination of Bacillus cereus spores. J. Bacteriol. 82:706–713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raber E, Burklund A. 2010. Decontamination options for Bacillus anthracis contaminated drinking water determined from spore surrogate studies. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:6631–6638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rice EW, Adcock NJ, Sivaganesan M, Rose LJ. 2005. Inactivation of spores of Bacillus anthracis Sterne, Bacillus cereus, and Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis by chlorination. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:5587–5589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rose LJ, Rice EW, Hodges L, Peterson A, Arduino MJ. 2007. Monochloramine inactivation of bacterial select agents. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:3437–3439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rose LJ, et al. 2005. Chlorine inactivation of bacterial bioterrorism agents. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:566–568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sarin P, Snoeyink VL, Lytle DA, Kriven WM. 2004. Iron corrosion scales: model for scale growth, iron release, and colored water formation. J. Environ. Eng. 130:364–373 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shane WT, Szabo JG, Bishop PL. 2011. Persistence of non-native spore forming bacteria in drinking water biofilm and evaluation of decontamination methods. Environ. Technol. 32:847–855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sivaganesan M, Adcock NJ, Rice EW. 2006. Inactivation of Bacillus globigii by chlorination: a hierarchical Bayesian model. J. Water Supply 55:33–43 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Szabo JG, et al. 2009. Bacillus spore uptake onto heavily corroded iron pipe in a drinking water distribution system simulator. Can. J. Civ. Eng./Rev. Can. Genie Civ. 36:1867–1871 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szabo JG, Rice EW, Bishop PL. 2007. Persistence and decontamination of Bacillus atrophaeus subsp. globigii spores on corroded iron in a model drinking water system. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:2451–2457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Titball RW, Manchee RJ. 1987. Factors affecting the germination of spores of Bacillus anthracis. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 62:269–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.USEPA 2008. Pilot-scale tests and systems evaluation for the containment, treatment, and decontamination of selected materials from T&E building pipe loop equipment (EPA/600/R08/016). EPA, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vary JC, Halvorson HO. 1965. Kinetics of germination of Bacillus spores. J. Bacteriol. 89:1340–1347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Young SB, Setlow P. 2003. Mechanisms of killing of Bacillus subtilis spores by hypochlorite and chlorine dioxide. J. Appl. Microbiol. 95:54–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]