Abstract

Background

Excitatory synaptic transmission in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) regulates the reinstatement of drug-seeking, an animal model of relapse in human drug addicts. However, the functional adaptations at NAc synapses that mediate reinstatement are not clearly understood.

Methods

We assessed the behavioral responses of mice to cocaine administration by measuring locomotor stimulation and the acquisition, extinction, and reinstatement of conditioned place preference. Synaptic function was then examined by preparing acute brain slices and performing whole cell voltage-clamp recordings from individual medium spiny neurons in the NAc shell.

Results

We find that reduced excitatory synaptic strength in the NAc shell is a common functional adaptation induced by multiple experiences known to cause reinstatement, including stress and drug re-exposure. The same synaptic adaptation is observed shortly after reinstatement of conditioned place preference by a cocaine priming injection.

Conclusions

This common synaptic modification associated with stress, drug re-exposure, and reinstatement defines a potential synaptic gateway to relapse.

Keywords: Addiction, Stress, Nucleus Accumbens, Synaptic Plasticity, Relapse, Reinstatement

Introduction

Drugs of abuse share a common capacity to commandeer synaptic plasticity in the mesolimbic dopamine system (1). In the nucleus accumbens (NAc) – a central component of the mesolimbic dopamine system – adaptations in glutamate transmission are specifically implicated in the reinstatement of cocaine-seeking (2), a prominent animal model of relapse (3). Manipulations of NAc glutamate signaling have profound effects on reinstatement by drug priming injections (2, 4, 5), stress (6), and drug-associated cues (7). However, few studies have directly examined changes in NAc excitatory synaptic function that occur following experiences that cause reinstatement and relapse.

Repeated cocaine exposure leads to an enhancement of NAc excitatory synaptic transmission that develops following the termination of drug exposure (7-11) and is reversed by re-exposure to cocaine (8, 10, 12) – one experience associated with relapse. Stressful events also provoke relapse in human drug addicts and reinstatement in animal models (3). While acute stress can modify synaptic function in many regions of the brain, including NAc (13), the effect of stress on NAc synaptic transmission has not previously been examined in animals with a history of cocaine exposure. Here, we find that cocaine treatment reverses the impact of stress on NAc excitatory synapses, leading to a loss of excitatory synaptic strength. This synaptic adaptation is also observed shortly after the reinstatement of cocaine-conditioned place preference, defining a potential synaptic gateway to reinstatement and relapse.

Methods and Materials

Male C57Bl/6J mice (Jackson Lab) were given at least one week to acclimate to housing conditions and were at least 4 weeks old at the beginning of each experiment. All procedures conformed to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Procedures for cocaine treatment and synaptic electrophysiology have been previously described (8, 12); details are provided in the Supplement. For forced swim stress, mice were placed in a 1L beaker containing ~800 mL of water at room temperature (~23°C). After swimming for 6 minutes, mice were lightly dried with a towel and returned to the home cage. This stress procedure elevates circulating levels of corticosterone and reinstates conditioned place preference in mice (14, 15). The place conditioning apparatus and procedure are described in the Supplement, along with details concerning statistical analysis.

Results

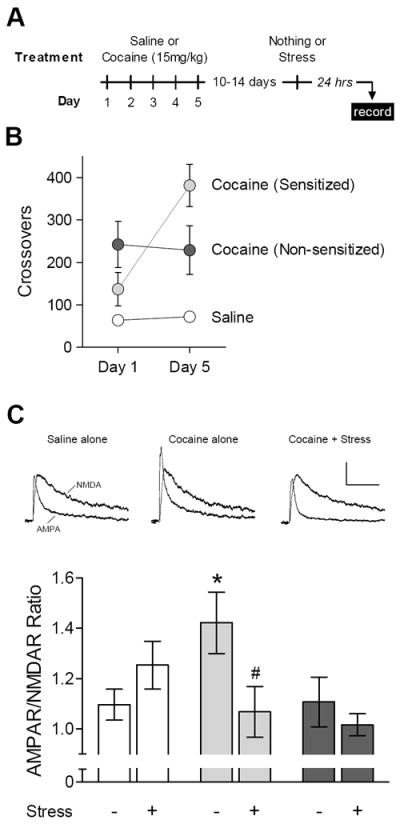

The locomotor responses following the first (Day 1) and last (Day 5) cocaine injection are presented in Figure 1B. Cocaine-treated mice were classified as sensitized if their locomotor response to cocaine increased more than 45% from the first to the last injection (see Supplement). Out of 19 cocaine-treated mice, 13 (68%) met this criterion and were classified as sensitized, while the remaining six mice (32%) were classified as non-sensitized. These proportions, as well as the tendency for a larger initial response to cocaine in non-sensitized animals, are similar to previous studies of cocaine sensitization in rats (10, 16). Ten to 14 days after the last injection, some mice from each treatment group were exposed to a single session of forced swim stress, and acute brain slices were prepared 24 hours later (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Stress after cocaine sensitization decreases NAc synaptic strength. (A) Experimental time line. (B) Locomotor activity following the first (Day 1) and last (Day 5) exposure to saline or cocaine. (C) Top: representative AMPAR and NMDAR EPSCs from saline alone, cocaine (sensitized) alone, and cocaine (sensitized) + stress. Calibration: 100 ms, 20 pA. Bottom: mean AMPAR/NMDAR ratio 24 hours after saline alone (n = 16/7); saline + stress (n = 18/7); cocaine (sensitized) alone (n = 13/5); cocaine (sensitized) + stress (n = 14/4); cocaine (non-sensitized) alone (n = 6/3); or cocaine (non-sensitized) + stress (n = 7/2). *Significant increase from saline alone; #significant decrease from cocaine (sensitized) alone.

We first measured the relative contributions of AMPA receptors (AMPARs) and NMDA receptors (NMDARs) to the synaptic current recorded at a holding potential of +40 mV. The AMPAR/NMDAR ratio is a measure of excitatory synaptic strength that has proven to be a sensitive assay for detecting synaptic adaptations caused by drug exposure (1). Analysis of the AMPAR/NMDAR ratio from all three treatment groups (Figure 1C) revealed a significant Group × Stress interaction [F(2,68) = 4.08, p = .021]. In the absence of stress, the AMPAR/NMDAR ratio was specifically increased in sensitized mice [p = .025 compared to saline]. Parallel changes in cell-surface expression of AMPARs have been reported in rats that develop cocaine sensitization (10, 16).

The increase in synaptic strength associated with cocaine sensitization was reversed 24 hours after a single session of forced swim stress (Figure 1C) [F(1,25) = 5.09, p = .033] – a manipulation that provokes reinstatement at this same time point (17). In the saline-treated control group, there was a non-significant tendency for stress to increase the AMPAR/NMDAR ratio [F(1,32) = 1.82, p = .19]. This increase in synaptic strength is more robust following a more intense stress protocol (13). Stress had no discernible effect in mice that did not develop cocaine sensitization [F(1,11) < 1], consistent with other evidence for correlated individual differences in sensitivity to stress and psychostimulant exposure (18).

The synaptic incorporation of AMPARs lacking the GluA2 subunit is increased in NAc following drug-free periods longer than 10-14 days (7, 9). However, we found no changes in the current-voltage relationship of AMPAR EPSCs (Figure S1 in the Supplement), suggesting alterations in the subunit composition of AMPARs did not lead to changes in the AMPAR/NMDAR ratio. This is consistent with our previous report that the current-voltage relationship of AMPAR EPSCs is not changed 10-14 days after repeated cocaine exposure (8). There were also no differences in the paired-pulse ratio that would indicate a change in the probability of glutamate release under any treatment condition (Figure S2 in the Supplement).

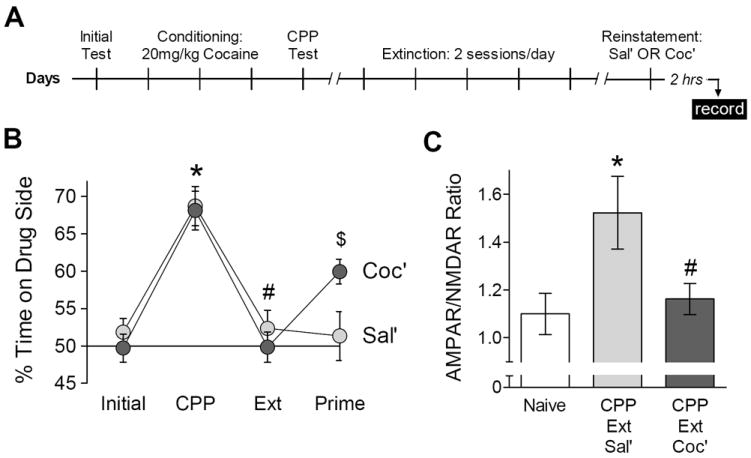

One striking aspect of these results is that the synaptic effect of stress in cocaine-treated animals mirrors the effect of cocaine re-exposure (8), indicating that this synaptic adaptation represents a common consequence of experiences that cause relapse in humans and reinstatement in animals models (3). To more directly assess this possibility, we examined the synaptic changes that accompany the reinstatement of cocaine-conditioned place preference (CPP) (Figure 2A). CPP was established by repeatedly injecting cocaine in the presence of distinct contextual cues, leading to a significant increase in time spent on the side of the apparatus associated with cocaine (Figure 2B, “CPP”) [F(1,25) = 81.58, p < .001]. CPP was then extinguished by repeatedly exposing animals to these cues in the absence of cocaine over 8-10 sessions, leading to a significant decrease in time spent on the drug side (Figure 2B, “Ext”) [F(1,25) = 232.4, p < .001] (Figure 2B). A priming injection of saline (Sal’) had no effect on extinguished cocaine CPP, but a priming injection of cocaine (Coc’) restored preference for the drug-related cues (Figure 2B, “Prime”) [Session × Prime interaction: F(1,25) = 12.67, p = .002].

Figure 2.

Reduced NAc synaptic strength following reinstatement of cocaine CPP. (A) Experimental time line. (B) Acquisition, extinction, and reinstatement of cocaine CPP following a priming injection of saline (Sal’, n = 13) or cocaine (Coc’, n = 14). *Significant increase compared to Initial; #significant decrease compared to CPP; $significant difference between Sal’ and Coc’. (C) Mean AMPAR/NMDAR ratio in NAc shell of naïve mice (n = 13/4) or two hours after priming injection with saline (n = 14/9) or cocaine (n = 15/8). *Significant increase compared to Naïve; #significant decrease compared to Sal’.

We prepared acute brain slices two hours after the priming injection, to allow cocaine to clear the system but still assess synaptic changes in close temporal proximity to the reinstatement event. Analysis of the AMPAR/NMDAR ratio from all three treatment groups revealed a significant main effect [F(2,39) = 4.51, p = .017]. Compared to an experimentally naïve control group, there was a net increase in the AMPAR/NMDAR ratio caused by CPP conditioning, extinction, and a priming injection of saline (Figure 2C) [p = .017]. This increase likely reflects the combined effects of cocaine exposure (8) and extinction training (6). However, a priming injection of cocaine reversed this increase in the AMPAR/NMDAR ratio (Figure 2C) [p = .037] – precisely the same synaptic adaptation observed 24 hours after cocaine re-exposure (8) or stress (Figure 1).

Conclusions

Our results indicate that stress and drug re-exposure, two experiences linked to relapse in human drug addicts, both cause a reduction of excitatory synaptic strength in the NAc shell of mice exposed to cocaine. This modification of synaptic function was observed 24 hours after forced swim stress, coincident with enhanced cocaine-seeking (17). The effect of stress in cocaine-treated mice contrasts with the effect of acute stress in drug-naïve mice, as the latter causes an increase in excitatory synaptic strength (13). Cocaine exposure thus reverses the impact of stress on NAc excitatory synapses, providing another example of cocaine-induced metaplasticity (8, 11). This altered sensitivity to stress may be one factor that leaves recovering drug addicts vulnerable to relapse.

The reinstatement of cocaine CPP was also accompanied by a reduction of excitatory synaptic strength in the NAc shell. This synaptic adaptation appeared to develop rapidly, as it was present only two hours after a priming injection of cocaine. These results are the first to demonstrate a common form of plasticity at NAc excitatory synapses triggered by different experiences associated with relapse. Cocaine-associated cues have also been shown to cause internalization of cell surface AMPARs in the NAc (10) – the biochemical parallel of a decrease in the AMPAR/NMDAR ratio. Although stress- and drug-induced reinstatement involve distinct upstream mechanisms (3), synaptic changes in NAc may be part of a convergent downstream pathway mediating reinstatement by both experiences. In our experimental preparation, stimulation at the rostral border of NAc in a parasagittal brain slice should prominently activate synaptic input from the prefrontal cortex (12). As prefrontal input to NAc shell arises primarily from infralimbic cortext (19), we speculate that the decrease in AMPAR/NMDAR ratio reflects a specific loss of excitatory drive from infralimbic cortex to medium spiny neurons in NAc shell, which promotes the reinstatement of extinguished drug-seeking behavior (20). This shared synaptic consequence of multiple experiences linked to relapse should inform the development of targeted therapeutic interventions to diminish the likelihood that abstinent drug addicts return to compulsive drug use.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Bonnie LaCroix and Hannah Christensen for technical assistance, Dr. Rob Malenka for critically reading the manuscript, and members of the Thomas lab for stimulating discussions. This work was supported by funding from the University of Minnesota Graduate School (to PER) and grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA007234 and DA023750 to PER, DA019666 to MJT) and the Whitehall Foundation (to MJT). PER is currently affiliated with the Neuroscience Institute, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA. SK is currently affiliated with the Cellular Neurobiology Research Branch, NIDA/NIH, Baltimore, MD.

Footnotes

Supplementary material cited in this article is available online.

Financial Disclosures

The authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kauer JA, Malenka RC. Synaptic plasticity and addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:844–858. doi: 10.1038/nrn2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalivas PW. The glutamate homeostasis hypothesis of addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:561–572. doi: 10.1038/nrn2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaham Y, Shalev U, Lu L, De Wit H, Stewart J. The reinstatement model of drug relapse: history, methodology and major findings. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;168:3–20. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1224-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bachtell RK, Choi KH, Simmons DL, Falcon E, Monteggia LM, Neve RL, et al. Role of GluR1 expression in nucleus accumbens neurons in cocaine sensitization and cocaine-seeking behavior. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:2229–2240. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidt HD, Pierce RC. Cocaine-induced neuroadaptations in glutamate transmission: potential therapeutic targets for craving and addiction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1187:35–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05144.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sutton MA, Schmidt EF, Choi KH, Schad CA, Whisler K, Simmons D, et al. Extinction-induced upregulation in AMPA receptors reduces cocaine-seeking behaviour. Nature. 2003;421:70–75. doi: 10.1038/nature01249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conrad KL, Tseng KY, Uejima JL, Reimers JM, Heng LJ, Shaham Y, et al. Formation of accumbens GluR2-lacking AMPA receptors mediates incubation of cocaine craving. Nature. 2008;454:118–121. doi: 10.1038/nature06995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kourrich S, Rothwell PE, Klug JR, Thomas MJ. Cocaine experience controls bidirectional synaptic plasticity in the nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci. 2007;27:7921–7928. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1859-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mameli M, Halbout B, Creton C, Engblom D, Parkitna JR, Spanagel R, et al. Cocaine-evoked synaptic plasticity: persistence in the VTA triggers adaptations in the NAc. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1036–1041. doi: 10.1038/nn.2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boudreau AC, Reimers JM, Milovanovic M, Wolf ME. Cell surface AMPA receptors in the rat nucleus accumbens increase during cocaine withdrawal but internalize after cocaine challenge in association with altered activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10621–10635. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2163-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moussawi K, Pacchioni A, Moran M, Olive MF, Gass JT, Lavin A, et al. N-Acetylcysteine reverses cocaine-induced metaplasticity. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:182–189. doi: 10.1038/nn.2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas MJ, Beurrier C, Bonci A, Malenka RC. Long-term depression in the nucleus accumbens: a neural correlate of behavioral sensitization to cocaine. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:1217–1223. doi: 10.1038/nn757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campioni MR, Xu M, McGehee DS. Stress-induced changes in nucleus accumbens glutamate synaptic plasticity. J Neurophysiol. 2009;101:3192–3198. doi: 10.1152/jn.91111.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kreibich AS, Blendy JA. cAMP response element-binding protein is required for stress but not cocaine-induced reinstatement. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6686–6692. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1706-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cleck JN, Ecke LE, Blendy JA. Endocrine and gene expression changes following forced swim stress exposure during cocaine abstinence in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;201:15–28. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1243-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boudreau AC, Wolf ME. Behavioral sensitization to cocaine is associated with increased AMPA receptor surface expression in the nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9144–9151. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2252-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conrad KL, McCutcheon JE, Cotterly LM, Ford KA, Beales M, Marinelli M. Persistent Increases in Cocaine-Seeking Behavior After Acute Exposure to Cold Swim Stress. Biol Psychiatry. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piazza PV, Le Moal M. Glucocorticoids as a biological substrate of reward: physiological and pathophysiological implications. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1997;25:359–372. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Voorn P, Vanderschuren LJ, Groenewegen HJ, Robbins TW, Pennartz CM. Putting a spin on the dorsal-ventral divide of the striatum. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:468–474. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peters J, LaLumiere RT, Kalivas PW. Infralimbic prefrontal cortex is responsible for inhibiting cocaine seeking in extinguished rats. J Neurosci. 2008;28:6046–6053. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1045-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.