Abstract

Social capital - especially through its ‘network’ dimension (high levels of participation in local community groups) - is thought to be an important determinant of health in many contexts. We investigate its effect on HIV prevention, using prospective data from a general population cohort in eastern Zimbabwe spanning a period of extensive behaviour change (1998-2003). Almost half of the initially uninfected women interviewed were members of at least one community group. In an ecological analysis of 88 communities, those with higher levels of community group participation had lower incidence of new HIV infections and more had adopted safer behaviours, although these effects were largely accounted for by differences in socio-demographic composition. Individual women in community groups had lower HIV incidence and more extensive behaviour change, even after controlling for confounding factors. Community group membership was not associated with lower HIV incidence in men, possibly reflecting a propensity amongst men to participate in groups that allow them to develop and demonstrate their masculine identities – often at the expense of their health. Support for women’s community groups could be an effective HIV prevention strategy in countries with large-scale HIV epidemics.

SOCIAL CAPITAL refers to the community cohesion that results from positive aspects of community life, particularly from high levels of civic engagement as reflected in membership of local voluntary associations (Putnam, 2000). A growing amount of evidence suggests that social capital is an important determinant of health in many contexts (Kim et al., 2008), and that certain forms of community group membership might predispose people to make more effective use of HIV/AIDS prevention, care and treatment services.

The high levels of interest in the concept of social capital in the HIV/AIDS field relate to growing consensus that the disappointing outcomes of many traditional biomedically and behaviourally oriented programmes may have been due in part to their failure to engage with pre-existing local community groups and resources, or to resonate with the perceived needs and interests of their target communities (Hawe and Shiell, 2000). In order to achieve such resonance, these programmes need to be supplemented by efforts to create ‘health-enabling community contexts’, social settings which support the likelihood that people will make optimal use of prevention, care and treatment services (Campbell et al., 2007, Campbell et al., 2009). Enhancing peoples’ opportunities for social participation in local community groups and networks is increasingly being put forward as a potential strategy for such community strengthening programmes in some contexts (Folland, 2007, Eriksson et al., 2010). However, participation in community groups is not always beneficial to health and a number of limitations have been noted (Veenstra, 2000, Ziersch and Baum, 2004).

In the HIV/AIDS field, social capital has been found to have protective effects on a range of factors associated with risk of infection including other sexually transmitted infections (Holtgrave and Crosby, 2003), sexual behaviour (Crosby et al., 2003), condom use (Albarracin et al., 2004), use of alcohol (Campbell et al., 2002) and intimate partner violence (Pronyk et al., 2008b). Social capital has also been found to mediate peoples’ access to AIDS-related health services and antiretroviral treatment (Binagwaho and Ratnayake, 2009, Ware et al., 2009), and to influence the extent to which people perpetuate or internalise AIDS stigma (Chiu et al., 2008).

Only a small number of studies have explored directly the influence of social capital on HIV acquisition (Campbell et al., 2002, Gregson et al., 2004b, Pronyk et al., 2008b). Whilst, these studies have found potentially protective effects of community group membership, their cross-sectional designs and focus on associations with prevalent (current) rather than incident (new) HIV infection status leave open the possibility that these findings may not be causal but, for example, be due to selective participation in community groups by ‘health conscious’ individuals (Dutta-Bergman, 2004). A further limitation of the existing literature on the relationship between community group membership and HIV acquisition is that, whilst social capital is conceived of often as being a property of communities, past studies have focussed exclusively on the relationship at the individual level.

In this article, we investigate the effect of community group membership on HIV incidence amongst women and men at both the ecological level and the individual level using prospective data from a population-based cohort study in communities in eastern Zimbabwe which have been subject to one of the largest generalised epidemics in sub-Saharan Africa. We describe recent patterns of group membership within these communities and find that overall membership levels are higher amongst women than amongst men and have fluctuated somewhat over a period of political and socio-economic instability. We show that communities with greater social capital tend to have lower levels of HIV incidence and less risky behaviour patterns amongst women, although this is explained, to some extent, by their older age-structures and less developed and more remote locations. At the individual level, we find that women who have participated in a wide range of different types of community groups have lower HIV incidence rates and are more likely to have adopted protective sexual behaviour than those with no prior participation in these groups. Men who participated in community groups also reported adopting safer behaviour but this did not translate into lower HIV incidence. We explore whether group membership could have facilitated the successful adoption of protective behaviours through knowledge diffusion or by increasing self-efficacy in these communities and identify some of the characteristics of groups that may influence their social capital value in supporting the adoption of low risk behaviours.

Community groups and reduced vulnerability to HIV infection: theoretical perspectives

Social capital research varyingly emphasises its ‘network’ dimension (high levels of participation in local community groups) (Foley and Edwards, 1999) and its ‘norm’ dimension (particularly levels of trust amongst community members) (Binagwaho and Ratnayake, 2009). However, Putnam (Putnam, 2000) argues that the network concept of associational membership is a more powerful marker of social capital than the ‘norm’ dimensions of trust and reciprocity. Furthermore, in our original research in Zimbabwe (Gregson et al., 2004b), we found no relationship between measures of trust and reciprocal help and support, the two ‘norm’ measures most frequently used in social capital research. Against this background, we define social capital in terms of peoples’ participation in local community groups (Campbell et al., 2002, Gregson et al., 2004b).

Community groups are seen to facilitate psychosocial determinants of healthy behaviours, first, because they provide networks for the diffusion of health-related information (knowledge diffusion) and, second, because the solidarity that arises from membership of a positively valued social group, with all the associated benefits of group membership, leads to higher levels of confidence in one’s ability to take control of one’s health (health-related agency or perceived self-efficacy (Bandura, 1977, Wallerstein, 1992)).

However, the influence of social capital on health is complex and varied and different studies have sometimes yielded apparently conflicting results. Social capital has been found to have negative as well as positive effects on health (Portes and Landolt, 1996) and the social capital value of a given community group in a particular context may lie on a continuum that ranges from the positive to the negative depending on its structural properties (Astone et al., 1999). Previously, we have suggested that this might be because the social capital ‘value’ of community groups in relation to improved health varies according to individual member and group characteristics (Gregson et al., 2004b).

At the individual level, the effect of group membership has been found to vary by gender (Norris and Inglehart, 2006, Pronyk et al., 2008b), ethnicity (Nhamo et al., In press), and educational attainment (Gregson et al., 2004b). At the level of the community groups themselves, it is believed that intra-group, inter-group and beyond group characteristics all can be important. Community groups can open up ‘social spaces’ for informal dialogue in which liked and trusted peers are able to ‘translate’ alien biomedical information into locally appropriate language and terminology that makes sense to group members, and to debate any reservations they might have about the value of the knowledge (renegotiation of peer norms). Such dialogue provides opportunities for peer group members to formulate health-enhancing action plans which are realistic in the light of locally mediated social, economic and cultural constraints on behaviour. Community groups may be more likely to facilitate improvements in health and healthcare when they create contexts for the development of a sense of comradeship and solidarity which boosts members’ confidence, social skills and sense of perceived self-efficacy (‘bonding social capital’) (Putnam, 2000, Saegart et al., 2001, Campbell and MacPhail, 2002, Wouters et al., 2009). At the same time, groups with a degree of diversity in their membership could increase the likelihood of programme success by putting members in touch with diverse and more powerful social groupings who provide support and assistance (‘bridging social capital’) (Campbell and Mzaidume, 2001, Skovdal et al., 2010). Other intra-group characteristics that could be important in determining the social capital value of a particular community group include whether the group functions effectively, the frequency and timing of meetings, whether the group has a horizontal or a hierarchical structure (Collier, 1998), whether meetings are cooperative or conflictual, the formality of meeting structures, whether meeting agendas are open or narrowly focussed, meeting settings, alcohol consumption and whether the group has external sponsorship (Gregson et al., 2004b). Inter- and extra-group ties through overlapping memberships, interactions with similar and different groups (Putnam, 1993, Woolcock, 2001), and provision of assistance for non-members also may be important.

Data and methods

The study was carried out in Manicaland, Zimbabwe’s eastern province between 1998 and 2005. This was a period of considerable political and socio-economic instability in Zimbabwe with the emergence of the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) opposition party in 1999, the defeat of a proposed new constitution in a national referendum in 2000, closely-fought parliamentary (2000 and 2005) and presidential (2002) elections, and a turbulent land redistribution process (starting in 2000). In the wake of these and other developments (e.g. Zimbabwe’s involvement in the war in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (1998) and the imposition of targeted sanctions (2002)), the economy went into a rapid decline in the early 2000s, with average real earnings dropping by more than 80% between 2001 and 2004 (International Monetary Fund, 2008). Extensive internal and international migration also occurred throughout this period.

The Manicaland Study was conducted in 12 locations comprising two small towns, two tea and coffee estates, two forestry plantations, two roadside trading settlements, and four subsistence farming areas. Most of the study sites were not directly affected by the land redistribution process, which was focussed on privately-owned commercial farms - two of the estates/plantations were owned by government controlled companies; the other two by international companies. However, the economic decline had a major impact through, for example, reductions in earnings and erosion of savings, whilst the highly-charged political environment impacted upon the extent and nature of social interactions.

We use prospective data from the Manicaland Study to measure and evaluate statistical associations between community group membership and risk of acquiring HIV infection at the population and individual levels. The detailed procedures followed in the study have been published previously (Gregson et al., 2006). In brief, a baseline census of all households in each location was carried out in a phased manner (one site at a time) between July 1998 and February 2000. A random sample of women aged 15-44 years and men aged 17-54 years resident within these households was recruited into a longitudinal general-population open-cohort survey, interviewed on a range of topics including socio-demographic characteristics, membership of community groups and sexual behaviour, and tested for HIV infection. First and second follow-up censuses and surveys were conducted 3 years (July 2001 to February 2003) and 5 years (July 2003 to August 2005) after baseline, respectively, in each location. All respondents at baseline and individuals who had previously been too young to participate but who now met the age criteria were considered eligible at each round of follow-up.

Following these procedures, 80% and 78% of eligible women and men, respectively, participated at baseline, 77% and 80% participated at first follow-up, and 87% and 79% participated at second follow-up. Sixty-six per cent of women and 54% of men interviewed at baseline - and not known to have died subsequently - were re-interviewed at first follow-up. The equivalent figures between the first and second follow-up surveys were 66% and 58%. Out-migration was the principal reason for loss-to-follow-up.

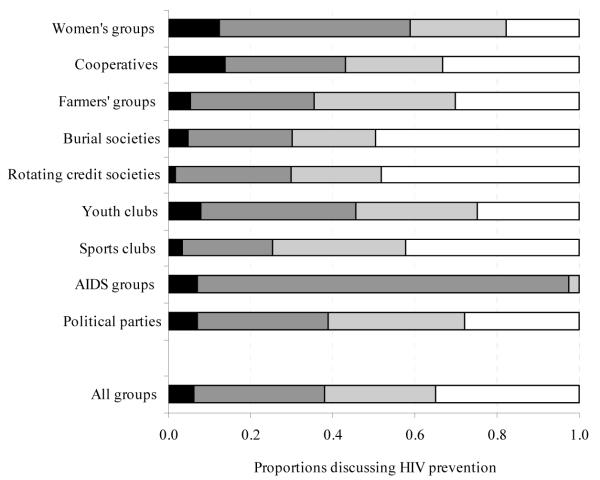

Here we use data primarily from the first two rounds of the Manicaland Study since these span the period (1998 to 2003) of widespread reductions in rates of sexual partner acquisition and the beginnings of an extended decline in HIV prevalence in Zimbabwe (Gregson et al., 2010, Zimbabwe Ministry of Health and Child Welfare, 2010). In an earlier analysis of cross-sectional data for young women, membership of community groups self-reported as functioning well was protective against HIV infection whilst membership of groups reported as functioning poorly was associated with increased risk of infection (Gregson et al., 2004b). Therefore, we treated study participants as being members of community groups if they reported membership of at least one group that they regarded as functioning effectively. Community groups identified specifically as “church groups” were not included since membership is very high (72% of women and 48% of men at baseline) and their social capital value in supporting safer sexual behaviours would have been difficult to distinguish from the effects of religious teaching. We examined the effects of community group membership on two main outcome indicators – incident HIV infection and adoption of safer behaviour during the 3-year inter-survey period – and (in the individual-level analysis) on two possible intermediary variables – increased knowledge about HIV/AIDS and increased self-efficacy measured over the same period. Respondents were considered to have adopted safer behaviour if they reported having been sexually active at baseline and reported fewer new sexual partners or no new partners in the last year. Data on sexual behaviour were collected using the Informal Confidential Voting Interview method to reduce social desirability bias (Gregson et al., 2004a). In each round of the survey, knowledge about HIV/AIDS was measured using an index constructed from responses to a series of questions about modes of transmission, protective measures and symptoms (Gregson et al., 1998). The median index scores at baseline were 59% for women and 61% for men. Self-efficacy was measured using responses to the question: “Do you think there are things you can do to avoid becoming infected with HIV?” The extent to which community groups provided social spaces for dialogue on HIV/AIDS (Figure 7) was measured at follow-up only using responses to a question on whether the group in which the participant spent most time discussed HIV prevention as part of their formal business agenda and/or in informal discussions.

FIGURE 7. Proportions of respondents (female and male) reporting formal and informal discussions about HIV/AIDS during group meetings, by form of community group.

For the ecological analysis of the effects of community group membership, the original 12 study locations were subdivided into clusters based on villages (in rural areas and roadside settlements), residential compounds (estates) and suburbs (small towns). Where a cluster had less than 10 individuals who qualified for a particular analysis (i.e., on the basis of sex, age and being uninfected at baseline), it was excluded from that analysis. In measuring the individual-level effects of community group membership over the inter-survey period, we compared outcomes, amongst previously uninfected women and men, between those who were members of community groups at baseline and those who were not. Thus, individuals who ceased to be members of groups during the study period were included while those who joined groups during this period were excluded.

Ecological level effects of community group membership

Social capital is conceived of most commonly as a property of communities. Therefore its effects should, wherever possible, be investigated at the population level. Before exploring the ecological association between group membership and HIV risk in the Manicaland Study data, we describe briefly the levels of community group membership over time across the different socio-economic strata represented in these data.

Trends in community group membership

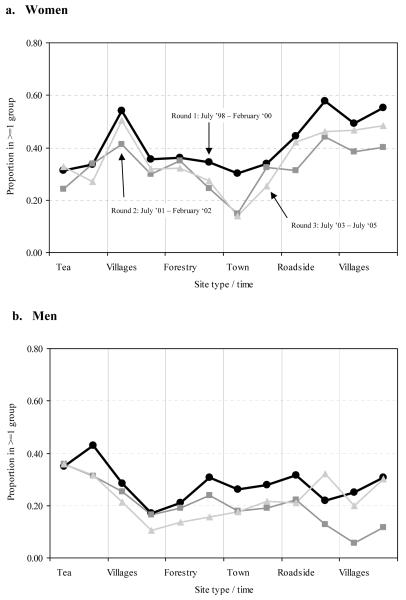

Overall group membership fluctuated somewhat during a turbulent period in Zimbabwe’s recent history (Figure 1), dropping from 43% (females) and 28% (males) in the late 1990s to 33% and 21%, respectively, in the early 2000s before recovering to 37% and 23% in the mid-2000s. Underlying these trends, there was considerable turnover of group membership. A third (34%) of the women who had reported membership of a group they regarded as functioning well in the first round of the survey had ceased to be a member of any group at all 3-years later at round two, and a further 5% reported that the group(s) they were participating in previously were no longer functioning well. The equivalent percentages for men were even higher - 61% and 11%.

FIGURE 1. Trends in community group membership by location, 1998-2005.

NOTE: The 12 sites covered by the Manicaland Study are enumerated in a fixed sequence in each round of the survey starting with the 2 tea estates, followed by 2 sites comprising rural villages, 2 forestry plantations, 2 small towns, 2 roadside trading settlements and finally 2 further sites comprising rural villages.

In the late 1990s, burial societies (community insurance schemes for funeral expenses) (22%), rotating credit societies (savings clubs for income generating projects) (18%) and women’s groups (sewing and other income-generating activities) (10%) were the most popular forms of groups for women, and sports clubs (11.5%) were the most popular type of group for men. Contrasting trends in membership levels were seen for different types of groups between the late 1990s and the mid-2000s, probably reflecting the effects of high AIDS mortality and rapidly escalating inflation. Burial societies (women: 22% to 21%; men: 5.5% to 7.5%), AIDS groups (women: 2% to 5%; men: 1% to 2%) and political groups (women: 3% to 7%; men: 2% to 7%) experienced stable or consistently rising membership over time whilst rotating credit societies (women: 18% to 10%; men: 10% to 4%) and women’s groups (10% to 5.5%) saw reductions in participation.

Ecological analysis

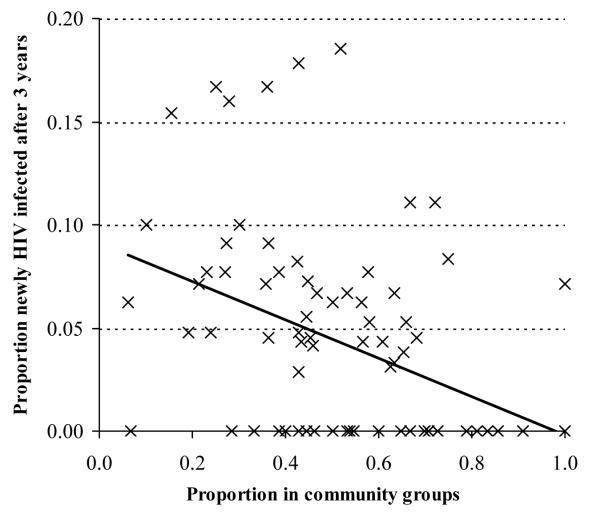

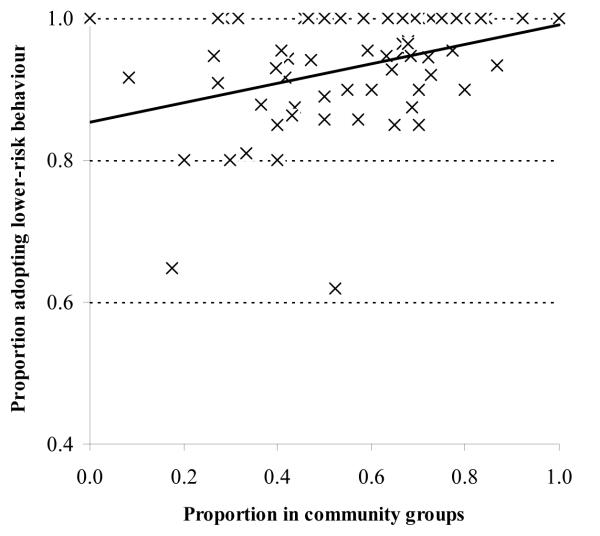

In our study sites in Zimbabwe, 88 out of a total of 222 clusters had 10 or more uninfected women at baseline. Amongst these clusters, as we show in Figure 2, those with greater proportions of women reporting membership of community groups at baseline had fewer new HIV infections over the following three year period (Ordinary least squares regression coefficient, −.090, p<.001). This effect was reduced after adjustment for differences in the mean ages of the women in the clusters (Coeff, −.056, p=.052) and reduced further after additional adjustment for socio-economic strata (town, estate, roadside and village) and level of education (Coeff, −.051, p=.1). For men, there were 47 clusters with 10 or more uninfected individuals at baseline and no evidence was found for lower HIV incidence in clusters with greater proportions of men participating in community groups (unadjusted Co-eff, +.043, p=.3).

FIGURE 2. Ecological level effect of participation in community groups on HIV incidence for women, Manicaland, Zimbabwe, 1998-2003.

Clusters with greater female membership of community groups also had higher proportions of women reporting adoption of safer behaviour (Coeff, +.131, p=.011, N=70). However, once again, the effect was reduced after adjustment for differences in the mean ages of the women in the clusters and for socio-economic strata and level of education (Coeff, +.047, p=.3). Clusters with greater male membership of community groups had similar proportions of men reporting adoption of safer behaviour to those with lower levels of male participation (Coeff, + .067, p=.6, N=37).

Individual-level effects of community group membership

We turn now to examining the association between membership of community groups and HIV risk at the individual level. This association could be confounded by other factors related both to participation in groups and to HIV risk. Therefore, we begin by identifying the characteristics of women who participate in community groups in our study areas.

Characteristics of group members

The data in Table 1 show that, within our cohorts of previously uninfected women and men, older, more educated and married individuals and those from the poorest households were more likely to report membership of community groups. Men living on commercial farms and men in employment were more likely to participate in community groups than those living in villages and those without jobs in the formal sector, respectively, whilst, the opposite was true for women in each instance. Women who belonged to a Christian church were also more likely to be members of community groups.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of HIV uninfected women and men, followed up after 3 years, by baseline membership of community groups

| Women |

Men |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group members |

Non- group members |

Test for difference |

Group members |

Non- group members |

Test for difference |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Socio-demographic characteristic | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | ||||

| All individuals | 0.51 | 0.49 | - | 0.31 | 0.69 | - |

| Age | ||||||

| Under 25 years | 0.29 | 0.71 | 1 | 0.29 | 0.71 | 1 |

| 25-39 years | 0.59 | 0.41 | 3.5 (2.9-4.3) | 0.32 | 0.68 | 1.1 (0.9-1.4) |

| 40 years and above | 0.75 | 0.25 | 7.1 (5.5-9.2) | 0.37 | 0.63 | 1.4 (1.0-1.9) |

| Residence | ||||||

| Village | 0.55 | 0.45 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.75 | 1 |

| Roadside settlement | 0.60 | 0.40 | 1.2 (0.9-1.5) | 0.31 | 0.69 | 1.4 (1.0-2.0) |

| Commercial farming estate | 0.39 | 0.61 | 0.5 (0.4-0.7) | 0.38 | 0.63 | 1.8 (1.4-2.3) |

| Town | 0.42 | 0.58 | 0.7 (0.5-0.9) | 0.28 | 0.72 | 1.1 (0.8-1.6) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single | 0.28 | 0.72 | 1 | 0.28 | 0.72 | 1 |

| Married | 0.59 | 0.41 | 1.4 (1.1-1.9) | 0.36 | 0.64 | 1.5 (1.1-2.0) |

| Divorced/separated | 0.35 | 0.65 | 0.6 (0.4-0.9) | 0.23 | 0.77 | 0.8 (0.4-1.7) |

| Widowed | 0.62 | 0.38 | 1.0 (0.6-1.7) | 0.29 | 0.71 | 0.6 (0.1-6.1) |

| Education | ||||||

| Primary or less | 0.57 | 0.43 | 1 | 0.30 | 0.70 | 1 |

| Secondary or more | 0.45 | 0.55 | 1.2 (1.0-1.5) | 0.32 | 0.68 | 1.3 (1.0-1.6) |

| Socio-economic status | ||||||

| Poorest tercile | 0.53 | 0.47 | 1 | 0.34 | 0.66 | 1 |

| Middle tercile | 0.54 | 0.46 | 0.9 (0.8-1.2) | 0.30 | 0.71 | 0.8 (0.6-1.1) |

| Least poor tercile | 0.45 | 0.55 | 0.6 (0.5-0.8) | 0.29 | 0.71 | 0.8 (0.6-1.0) |

| Employment | ||||||

| Unemployed | 0.51 | 0.49 | 1 | 0.27 | 0.73 | 1 |

| Employed | 0.43 | 0.57 | 0.6 (0.5-0.9) | 0.37 | 0.63 | 1.6 (1.3-1.9) |

| Religion | ||||||

| None | 0.28 | 0.72 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.75 | 1 |

| Traditional | 0.31 | 0.69 | 1.1 (0.5-2.4) | 0.36 | 0.64 | 1.6 (1.1-2.5) |

| Christian | 0.52 | 0.48 | 3.0 (1.8-4.9) | 0.31 | 0.69 | 1.3 (0.9-2.0) |

| N | 2374 | 1673 | ||||

aOR, age-adjusted odds ratio for membership of a well-functioning group

Individual-level effects of community group membership

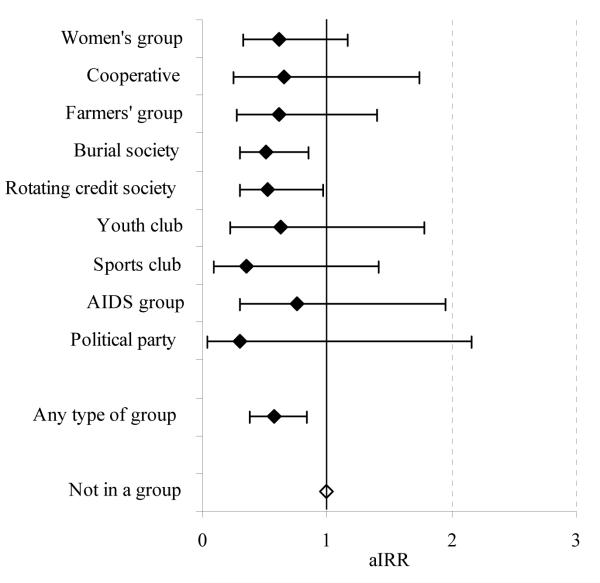

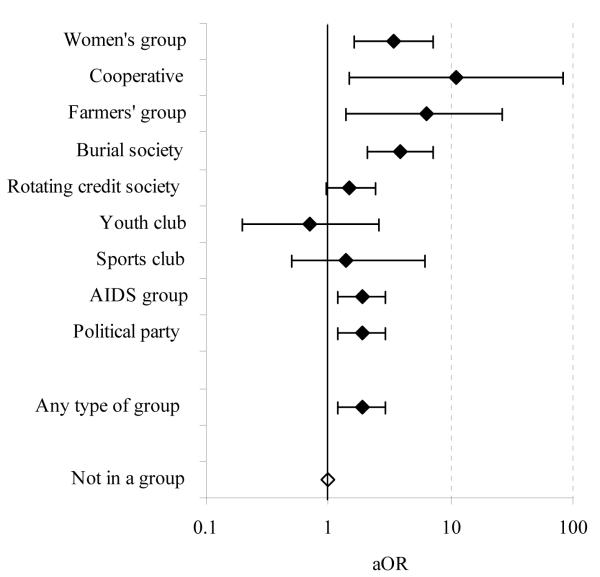

The incidence rate of new HIV infections between 1998 and 2003 was lower amongst women who were members of community groups (0.97%) than in other women (2.19%). This difference continued to be statistically significant after controlling for age, previous risk behaviour, location of residence, marital status, religion, education, poverty and employment (Table 2). Furthermore, the same trend was seen over a wide range of different types of groups (Figure 4). Amongst men, HIV incidence was higher in members of community groups (2.60% versus 1.71%) but this difference ceased to be statistically significant after controlling for age (p=.1). The pattern of association between community group membership and HIV incidence varied amongst the different types of groups with no significant effects being seen.

TABLE 2.

Impact of social group membershipa on risk of acquiring HIV infection (1998-2000 to 2001-2003), Manicaland, Zimbabwe, by type of group

| Women |

Men |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV incidence |

Incidence rate ratiob |

HIV incidence |

Incidence rate ratiob |

|||||||||

| Type of group | Infections / pyrs |

% (95% CI) |

Unadjusted (95% CI) |

Age-adjusted (95% CI) |

Fully-adjustedd (95% CI) |

N | Infections / pyrs |

% (95% CI) |

Unadjusted (95% CI) |

Age-adjusted (95% CI) |

Fully-adjustedd (95% CI) |

N |

| Women’s group | 10/915 | 1.09 (0.59, 2.03) |

0.51 (0.29, 0.91) |

0.62 (0.33, 1.16) |

0.75 (0.40, 1.42) |

305 | - | |||||

| Cooperative | 5/523 | 0.96 (0.40, 2.30) |

0.45 (0.20, 1.02) |

0.66 (0.25, 1.74) |

0.87 (0.32, 2.37) |

174 | 3/124 | 2.43 (0.78, 7.52) |

1.41 (0.45,4.41) |

1.46 (0.47, 4.49) |

1.40 (0.48, 4.07) |

42 |

| Farmers’ group | 5/579 | 0.86 (0.36, 2.08) |

0.40 (0.18, 0.89) |

0.61 (0.27, 1.40) |

0.78 (0.34, 1.83) |

193 | 2/141 | 1.42 (0.36, 5.68) |

0.84 (0.20, 3.49) |

0.77 (0.18, 3.29) |

0.71 (0.16, 3.08) |

47 |

| Burial society | 17/2081 | 0.82 (0.51, 1.31) |

0.38 (0.24, 0.62) |

0.51 (0.30, 0.85) |

0.62 (0.37, 1.05) |

691 | 4/359 | 1.11 (0.42, 2.97) |

0.66 (0.24, 1.79) |

0.63 (0.23, 1.77) |

0.43 (0.14, 1.32) |

120 |

| Rotating credit society | 14/1444 | 0.97 (0.57, 1.64) |

0.45 (0.26, 0.80) |

0.53 (0.30, 0.95) |

0.61 (0.35, 1.08) |

483 | 19/487 | 3.90 (2.49, 6.12) |

2.18 (1.27, 3.76) |

1.84 (1.04, 3.25) |

1.83 (0.99, 3.38) |

172 |

| Youth club | 4/305 | 1.31 (0.49, 3.50) |

0.60 (0.23, 1.59) |

0.63 (0.22, 1.78) |

0.68 (0.22, 2.08) |

103 | 4/193 | 2.07 (0.78, 5.53) |

1.22 (0.48, 3.08) |

1.32 (0.51, 3.39) |

1.42 (0.55, 3.69) |

65 |

| Sports club | 2/288 | 0.69 (0.17,2.78) |

0.32 (0.09, 1.23) |

0.35 (0.09, 1.41) |

0.41 (0.11, 1.57) |

96 | 16/596 | 2.68 (1.64, 4.38) |

1.56 (0.92, 2.65) |

1.63 (0.94, 2.82) |

1.61 (0.92, 2.83) |

203 |

| AIDS group | 3/227 | 1.32 (0.04,4.10) |

0.61 (0.24, 1.60) |

0.76 (0.30, 1.95) |

0.93 (0.36, 2.35) |

76 | 1/40 | 2.48 (0.35, 17.62) |

1.41 (0.21, 9.55) |

1.50 (0.24, 9.53) |

1.17 (0.18, 7.56) |

14 |

| Political party | 1/211 | 0.47 (0.07, 3.37) |

0.22 (0.03, 1.55) |

0.30 (0.04,2.16) |

0.34 (0.05, 2.47) |

71 | 3/132 | 2.27 (0.73, 7.03) |

1.32 (0.46, 3.72) |

1.26 (0.43, 3.66) |

0.86 (0.28, 2.64) |

45 |

| Any type of group | 35/3607 | 0.97 (0.70, 1.35) |

0.45 (0.30, 0.68) |

0.57 (0.38, 0.84) |

0.64e (0.43, 0.94) |

1,206 | 40/1539 | 2.60 (1.91, 3.54) |

1.50 (1.00,2.24) |

1.46 (0.94, 2.28) |

1.46e (0.95, 2.24) |

527 |

| Not a member at round 1c | 75/3424 | 2.19 (1.75,2.75) |

1 | 1 | 1 | 1,168 | 58/3388 | 1.71 (1.32, 2.21) |

1 | 1 | 1 | 1,146 |

Member = member of at least one well-functioning community group

Incidence rate ratios compared with women and men who were not members of any well-functioning community groups at round 1; all adjusted for clustering at the village-level

Irrespective of whether a member at round 2

Adjusted for age, previous risk behaviour, location of residence, marital status, religion, education, poverty and employment

After additional adjustment for knowledge about HIV/AIDS at round 1: women - aIRR=0.56 (0.38,0.83); men - aIRR=l .46 (0.97, 2.21)

FIGURE 4. Individual level effect of participation in community groups on HIV incidence: age-adjusted incidence rate ratio (aIRR) for HIV infection for women in community groups at baseline compared to those not in a group, by type of group, Manicaland, Zimbabwe, 1998-2003.

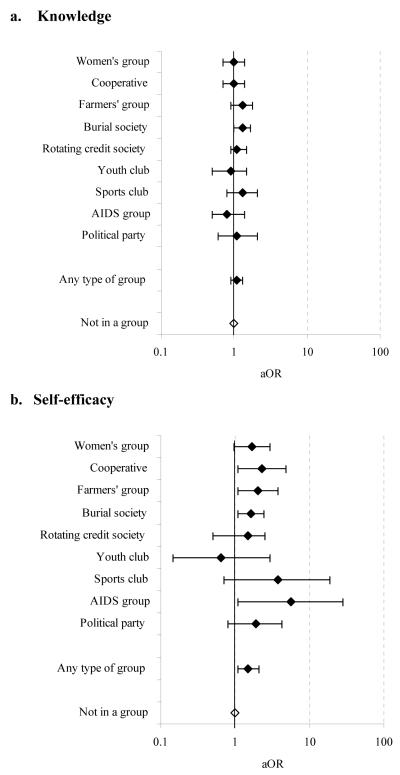

Adoption of less risky sexual behaviour was also more common in women who were members of community groups at baseline (Table 3). Amongst the sexually active women in community groups, 96.2% had either kept to a single partner or had reduced their number of sexual partners in the last year compared to 90.1% of other sexually active women. Once again, this effect remained statistically significant after controlling for known confounding factors and was observed across a wide range of different types of community groups (Figure 5). Adoption of less risky behaviour was also reported more frequently by men who were members of community groups than by other men (78.3% versus 72.9%. A similar pattern was seen in most types of groups.

TABLE 3.

Impact of social group membershipa on reducing or maintaining low-risk behaviour (1998-2000 to 2001-2003), Manicaland, Zimbabwe, by type of group

| Women |

Men |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behaviour change |

Odds ratiob |

Behaviour change |

Odds ratiob |

|||||||

| Type of group | n/N | % (95% CI) |

Unadjusted (95% CI) |

Age-adjusted (95% CI) |

Fully-adjustedd (95% CI) |

n/N | % (95% CI) |

Unadjusted (95% CI) |

Age-adjusted (95% CI) |

Fully-adjustedd (95% CI) |

| Women’s group | 295/301 | 98.0 (96.4, 100.0) |

5.5 (2.5, 12.1) |

3.4 (1.6,7.1) |

2.7 (1.3,6.0) |

- | ||||

| Cooperative | 169/170 | 99.4 (98.3, 100.0) |

19.3 (2.6, 143.8) |

11.0 (1.5, 81.9) |

7.5 (1.0, 57.3) |

30/35 | 85.7 (73.5, 97.9) |

2.3 (1.0, 5.2) |

1.7 (0.8, 3.9) |

1.7 (0.7, 4.0) |

| Farmers’ group | 191/193 | 99.0 (97.5, 100.0) |

11.4 (2.8,46.6) |

6.3 (1.5,26.6) |

4.5 (1.0, 19.6) |

41/46 | 89.1 (79.8, 98.5) |

3.0 (1.2, 7.7) |

2.1 (0.8, 5.4) |

2.7 (0.9, 8.2) |

| Burial society | 668/681 | 98.1 (97.1, 99.1) |

6.1 (3.3, 11.1) |

3.9 (2.1,7.1) |

3.1 (1.6, 5.9) |

85/106 | 80.2 (72.5, 87.9) |

1.5 (0.9, 2.4) |

1.1 (0.7, 1.9) |

1.1 (0.7, 1.9) |

| Rotating credit society | 451/474 | 95.1 (93.2, 97.1) |

2.3 (1.4,3.6) |

1.5 (0.95, 2.4) |

1.7 (1.0,2.7) |

126/155 | 81.3 (75.1, 87.5) |

1.6 (1.2, 2.3) |

1.5 (1.0, 2.2) |

1.5 (1.0,2.3) |

| Youth club | 15/18 | 83.3 (64.3, 100.0) |

0.6 (0.2, 2.2) |

0.7 (0.2,2.6) |

0.6 (0.2,2.1) |

30/43 | 69.8 (55.5, 84.1) |

0.8 (0.5, 1.5) |

1.2 (0.7, 2.3) |

1.2 (0.6, 2.2) |

| Sports club | 46/49 | 93.9 (86.9, 100.0) |

1.9 (0.4, 8.6) |

1.4 (0.3, 6.2) |

0.9 (0.2, 3.8) |

119/159 | 74.8 (68.0, 81.7) |

1.1 (0.8, 1.6) |

1.4 (1.0, 2.0) |

1.4 (1.0,2.1) |

| AIDS group | 58/62 | 93.5 (87.3, 99.8) |

1.8 (0.6, 5.3) |

1.1 (0.4,3.2) |

0.9 (0.3,2.9) |

9/12 | 75.0 (46.3, 100.0) |

1.2 (0.3, 4.6) |

1.3 (0.3, 5.3) |

1.2 (0.2, 5.8) |

| Political party | 68/71 | 95.8 (91.0, 100.0) |

2.4 (0.9, 6.8) |

1.3 (0.5,3.6) |

1.4 (0.6,3.3) |

32/42 | 76.2 (62.8, 89.6) |

1.2 (0.6, 2.2) |

0.8 (0.4, 1.6) |

1.0 (0.5, 1.9) |

| Any type of group | 1032/1073 | 96.2 (94.9, 97.2) |

2.9 (1.9,4.4) |

1.9 (1.2,2.9) |

1.8e (1.2,2.8) |

340/434 | 78.3 (74.2, 82.1) |

1.3 (1.1, 1.7) |

1.3 (1.0, 1.7) |

1.4e (1.0, 1.8) |

| Not a member at Rlc | 785/871 | 90.1 (87.9, 92.0) |

1 | 1 | 1 | 653/896 | 72.9 (69.8, 75.8) |

1 | 1 | 1 |

Member = member of at least one well-functioning community group

Odds ratios compared with women and men who were not members of any well-functioning community groups at round 1; all adjusted for village-level clustering and interview method

Irrespective of whether a member at round 2

Adjusted for age, previous risk behaviour, location of residence, marital status, religion, education, poverty and employment

After additional adjustment for knowledge about HIV/AIDS at round 1: women, aOR=l .9 (1.2, 2.9); men, aOR=l .4 (1.1,1.9)

FIGURE 5. Individual level effect of participation in community groups on adoption of lower risk sexual behaviour: age-adjusted odds ratio (aOR) for behaviour change for women in community groups at baseline compared to those not in a group, by type of group, Manicaland, Zimbabwe, 1998-2003.

Psychosocial determinants of healthy behaviour

According to the theory on social capital, community group membership can lead to increases in healthier behaviours by facilitating the development of individual psychosocial characteristics that support the adoption of these behaviours. In particular, this can occur through knowledge diffusion and increases in perceived self-efficacy.

In our study populations, women who were already members of community groups had better knowledge about HIV/AIDS at baseline (Gregson et al., 2004b). However, we found that membership of community groups had led to only modest improvements in knowledge about HIV/AIDS during the follow-up period. Thirty-five percent of the women who reported membership of community groups at baseline had improved their score on the knowledge index by 5% or more during the inter-survey period compared with 31% of the women who had not previously been members of these groups. Furthermore, the difference was only statistically significant for members of burial societies (Figure 6a). In contrast, a larger increase in the proportion of women who believed there were things they could do to avoid becoming infected with HIV (self-efficacy) occurred between 1998 and 2003 amongst those who were members of community groups than amongst those that were not (26% versus 15%). This trend was observed in all forms of groups except youth clubs (Figure 6b).

FIGURE 6. Individual level effect of participation in community groups on psychological determinants of HIV infection: age-adjusted odds ratio (aOR) for increased knowledge about HIV/AIDS and self-efficacy for women in community groups at baseline compared to those not in a group, by type of group, Manicaland, Zimbabwe, 1998-2003.

Similar proportions of men who were participating and not participating in community groups at baseline (37% in each case) had improved their score on the knowledge index by 5% or more during the inter-survey period. There were no signs in the data of variations by type of group. Most men in the cohort believed there were things they could do to avoid becoming infected with HIV and the proportion increased over time from 93% to 97%; however, no difference was found between the increases in those who were members of community groups and those who were not.

Characteristics of community groups that may assist their members in reducing HIV risk

In the second round of the Manicaland Study (2001-2003), we collected data on group characteristics suggested in the literature (Gregson et al., 2004b) as potentially enhancing the effect of community groups in assisting their members to avoid HIV infection (Table 4). We found that community groups generally met on a regular basis (53% of members reported meeting weekly and a further 40% said they met monthly). Two-thirds of the respondents (65%) reported discussing HIV/AIDS issues during their meetings either as part of the formal agenda or informally and there was evidence that this was the case not only in AIDS groups but in groups as diverse as sports clubs and farmers groups (Figure 7). In most cases, meetings were said to be cooperative (90%) rather than conflictual (10%).

TABLE 4.

Characteristics of community groups formed by women and men (2001-2003), Manicaland, Zimbabwe, by type of groupa

| Meeting frequency |

AIDS discussions |

Gender balance |

Age mix | Education mix |

Sponsorshipb | Alcohol | Cooperative vs. conflictual |

Networking | Participation | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Meet at least monthly |

Formal or informal discussions |

Proportion male |

Proportion <20 years |

Proportion attended secondary school |

Members drink during or after meetings |

Assist or meet with other groups |

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Type of group | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Test for diff* |

| Women’s group | 0.95 | - | 0.82 | - | 0.01 | - | 0.09 | - | 0.45 | - | 0.46 | - | 0.14 | - | 0.98 | - | 0.57 | - | 0.06 | - | - |

| Cooperative | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.13 | 0.68 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.38 | 0.54 | 0.46 | 0.50 | 0.26 | 0.67 | 0.97 | 0.92 | 0.74 | 0.67 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 2.7(1.9,4.0) |

| Farmers’ group | 0.93 | 0.83 | 0.68 | 0.73 | 0.24 | 0.71 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.36 | 0.45 | 0.58 | 0.73 | 0.58 | 0.76 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.75 | 0.85 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 1.5(1.1,2.1) |

| Burial society | 0.97 | 0.91 | 0.48 | 0.64 | 0.19 | 0.53 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.40 | 0.47 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.39 | 0.66 | 0.94 | 0.98 | 0.50 | 0.35 | 0.19 | 0.04 | 4.3(3.5, 5.3) |

| Rotating credit society | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.49 | 0.64 | 0.05 | 0.86 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.44 | 0.67 | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.55 | 0.94 | 0.97 | 0.35 | 0.30 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 5.1 (4.0,6.4) |

| Youth club | 0.94 | 0.82 | 0.80 | 0.71 | 0.33 | 0.51 | 0.60 | 0.55 | 0.66 | 0.65 | 0.78 | 0.65 | 0.23 | 0.52 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.81 | 0.91 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.6(0.5,0.8) |

| Sports club | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.38 | 0.62 | 0.23 | 0.94 | 0.47 | 0.36 | 0.74 | 0.64 | 0.69 | 0.68 | 0.19 | 0.74 | 0.91 | 0.81 | 0.78 | 0.94 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.3 (0.2, 0.3) |

| AIDS group | 0.95 | 0.91 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.19 | 0.44 | 0.18 | 0.30 | 0.48 | 0.60 | 0.86 | 0.73 | 0.41 | 0.42 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 1.5(1.1,2.0) |

| Political party | 0.82 | 0.68 | 0.61 | 0.82 | 0.45 | 0.64 | 0.21 | 0.27 | 0.42 | 0.54 | 0.82 | 0.98 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.88 | 0.82 | 0.90 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 1.6(1.2,2.0) |

| All groups | 0.95 | 0.88 | 0.62 | 0.70 | 0.17 | 0.74 | 0.15 | 0.28 | 0.45 | 0.61 | 0.42 | 0.60 | 0.34 | 0.69 | 0.94 | 0.89 | 0.61 | 0.70 | 0.33 | 0.21 | 1.8(1.6,2.0) |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Test for gender differencec | 2.4(1.4,4.1) | 0.7(0.5, 0.9) | - | 0.5 (0.4, 0.7)e | 0.7(0.3, 1.5)e | 0.6(0.4, 0.7) | 0.2(0.1,0.3) | 1.3(0.8, 2.0) | 0.4(0.3, 0.6) | - | |||||||||||

| Test for gender differencd | 2.1 (1.2, 3.8) | 0.6(0.4, 0.8) | - | 1.1 (0.8, 1.6)e | 0.8(0.4, 1.9)e | 1.0(0.7, 1.5) | 0.2(0.2, 0.3) | 0.8(0.5, 1.3) | 0.8(0.6, 1.2) | - | |||||||||||

Estimates are averages of reports by individual female and male group members interviewed in the second round of the survey (including individuals already infected with HIV at baseline)

Sponsored by a church, school, NGO, political party, employer or other external body

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for reporting group characteristic, women compared to men, adjusted for age and location

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for reporting group characteristic, women compared to men, adjusted for age, location and type of group

For age mix, odds ratio for reporting 20% or more members aged under 20 years; for education mix, odds ratios for reporting 50% or more members with secondary education

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for reporting membership of a functional community group, women compared to men, adjsuted for age and location

There was considerable heterogeneity in the membership of the individual groups. For example, 52% of women and 45% of men reported that the group they spent most time in also had members from the opposite sex. Most groups had members from different educational backgrounds. Teenagers participated to some extent in all groups but, as would be expected, particularly so in youth groups and sports clubs.

Slightly less than half of the women and men in community groups reported that their groups received sponsorship – with non-governmental organisations (18%), churches (16%), political parties (15.5%), employers (8%) and schools (5%) being common sources of assistance. Two-thirds (68%) of respondents reported that the community groups they spent most time in assisted or met with other groups of the same or different types and half (54%) said their groups interacted with members of the wider community.

Comparison of characteristics of community groups joined by women and men

As we noted earlier, women and men tended to join different types of community groups. Women were more likely to participate in rotating credit societies, burial societies and cooperatives and, to a lesser extent, farmers’ groups, AIDS groups and political parties. Men predominated in sports clubs and youth groups.

More women than men reported that the community group they spent most time in held meetings at least once a month (Table 4) but fewer were in a group that discussed AIDS, a group with young people, a group with a high proportion of more educated people, a group with external sponsorship, a group where members drank alcohol or a group that assisted or met with other groups. Some of these differences reflected underlying differences in the types of groups that men and women participated in. The burial societies and rotating credit societies favoured by women rarely received external support or assisted other groups whilst the sports clubs and youth clubs preferred by men generally had younger members and were often sponsored by schools or employers. Once contrasts between the types of groups that women and men joined were taken into account, the only differences that remained were in AIDS discussions and alcohol consumption. When analysis is restricted to discussions held as part of the formal meeting agenda, women were more likely than men to report discussing AIDS in the course of group meetings (42% versus 32%, age- and location-adjusted odds ratio (aOR), 1.50, 95% CI, 1.16, 1.94). This difference was explained by women’s greater propensity to join types of groups that hold formal discussions about AIDS (e.g. women’s groups, youth clubs and AIDS groups).

Discussion

As has been the case in the country as a whole (Gregson et al., 2010), HIV prevalence in adults has been falling in our study populations in eastern Zimbabwe since the late 1990s – from 23% to 18% over the period 1998 to 2005 (Gregson et al., 2007). This fall in HIV prevalence appears to have followed an acceleration in the rate of decline of new infections between 1999 and 2004 (Hallett et al., 2009) driven, in part, by reductions in rates of sexual partner acquisition (Gregson et al., 2006). These changes in behaviour are believed to have resulted from social changes driven by increased awareness of AIDS deaths aided by HIV prevention programs utilizing both mass media and church-based, workplace-based, and other interpersonal communication activities (Halperin et al., 2011). Our findings here suggest that these social changes also may have been facilitated by high levels of social capital in the form of female civic engagement. Almost half of the previously uninfected women in our population-based cohort were members of community groups at recruitment and a higher proportion of these women than of their peers who were not members of groups reported adopting lower rates of sexual partner acquisition during the following three years and fewer became infected with HIV. Similar effects were seen also at the ecological level of analysis although the associations were reduced after adjustment for differences in age, location and education.

Participation in community groups appears to have helped women to adopt safer behaviours and to avoid HIV infection primarily through increased self efficacy, an individual level characteristic which is protective against HIV infection in this population (Gregson et al.). Amongst women who had previously said they did not know what to do to avoid becoming infected with HIV, those who were members of community groups were much more likely to report feeling able to protect themselves from infection at follow-up. Thus, improved health-related agency stemming from community group activities could have played a part in helping women to adopt safer behaviours.

Past studies on the effects of social capital on health sometimes have appeared to yield conflicting results. Much of the complexity of social capital may lie in differences in how it is used, defined and measured. Indeed Pronyk and colleagues noted recently that “Despite over a decade’s experience, there is no universally accepted way to measure social capital” (Pronyk et al., 2008b). In their own study of poor households in rural Limpopo province in South Africa, community group membership was associated with greater risk of HIV infection in women (Pronyk et al., 2008b). However, the apparent discrepancy between this finding and the results for women in the current study may be explained by differences in the way group membership was measured (intensity of membership versus quality of group functioning; household level versus individual level reporting), in the biological specimens used to detect the presence of HIV infection (oral-mucosal transudate versus dried blood spot specimens), and in the variables controlled for in the statistical analyses (prior history of high risk sexual behaviour was not controlled for in the South Africa study), as well as by differences in some of the factors discussed in the following two paragraphs.

Differences in study methods notwithstanding, it seems clear that social capital does vary in the effect it has on health outcomes (Portes and Landolt, 1996). We have suggested that this may reflect differences in local context, local patterns of group membership, and group and individual member characteristics (Gregson et al., 2004b). The contrasting effects on HIV incidence in women and men found in the current study may reflect gender differences in some of these factors.

The groups in which women participated in our study communities in eastern Zimbabwe appear to have had a number of positive features. Almost all groups met at least once a month and HIV prevention was discussed formally as well as informally by a wide variety of different types of groups, indicating that community groups provide numerous social spaces for dialogue about HIV prevention in the study areas. Meetings were reported overwhelmingly as being cooperative and the involvement of, for example, more and less educated individuals within the same groups, together with extensive interaction with other groups and the wider community, testify to high levels of ‘bridging’ social capital.

In contrast to these findings for women, we found little evidence that membership of community groups had assisted men in avoiding HIV infection. We found somewhat greater reductions in reported sexual risk behaviour amongst male group participants but these did not translate into lower incidence of new HIV infections. Furthermore, group membership was not associated with larger increases in knowledge or self-efficacy in men. A number of factors may help to explain the different findings for women and men. These include the greater and longer-term participation of women in community groups, the pre-existing high levels of self-efficacy seen amongst men, and the differences in the types and characteristics of the groups joined by women and men. Men generally have been found to be less likely to join groups where AIDS is discussed (Lyttleton, 2004, Skovdal et al., In press) and this was true in the current study for formal discussions about AIDS. Men who did participate in community groups in Manicaland were more likely to join groups such as sports clubs and political parties, groups that exhibit competitiveness and power rather than care and sustaining of household livelihoods (e.g. AIDS groups, burial societies and credit associations), a tendency which is linked intrinsically to gender and local constructions of masculinities (Barker and Ricardo, 2005). For example, in South Africa, Ragnarsson and colleagues (Ragnarsson et al., 2009) found that the kind of community groups and networks that men typically engage with mirror masculinities that actively encourage multiple sexual partners and related high risk behaviours. This, coupled with men’s greater propensity to be in groups that drink alcohol during or after meetings (69% of men versus 34% of women in the current study), suggests that community groups are often used by men, not as a means to protect their family, but as a way to develop and demonstrate their masculine identities – often at the expense of their health. Acknowledging social constructions of masculinity as a barrier to health and well-being, growing efforts are being made to document the pathways through which men can create social spaces to renegotiate and develop more health-enabling masculinities (Barker and Ricardo, 2005, Colvin and Robins, 2009, Burke et al., 2010).

One of the main strengths of this study is its use of an actual health outcome (HIV incidence) rather than purely self-rated outcomes. However, a limitation is its reliance on self-reported data on group membership and characteristics (including whether or not the group functioned effectively). The data on sexual behaviour were also self-reports but were collected using a confidential method that has been shown to reduce bias in the study populations and are credible since the results largely match those for HIV incidence (Lopman et al., 2008). Participation in community groups in Manicaland is selective. Differences in individual characteristics between group members and non-members at baseline were controlled for in the main analyses and types of groups with different patterns of membership showed similar trends in reducing HIV incidence. However, we were not able to capture unobservable characteristics of respondents in the study so selective participation may have had some residual effect on the findings of the study. The evidence for ecological associations between levels of group membership and HIV risk in women was weak possibly because establishment of ecological evidence of impact of group membership is more difficult when communities are loosely defined and groups are not specific to particular communities as was the case in this study. We excluded community groups identified specifically as “church groups” from the analysis; if the effect of women’s participating in these groups (over and above any effect of religious teaching) is similar to that observed for other forms of groups, the overall contribution of community group membership to reductions in HIV incidence could be even greater.

The effect of community group membership appears to have been particularly important during the period up to 2003. Whereas women who participated in these groups were at lower risk of having contracted HIV infection prior to baseline (1998-2000) (Gregson et al., 2004b) and experienced fewer new infections over the period 1998-2003, no effect on HIV incidence was observed in the following two years - i.e. between the second and third rounds of our survey (data not shown). Overall, there were fewer new infections during this period (resulting in less statistical power in our study to detect differences) and group members, having adopted less risky behaviours already, had less scope for further reductions.

Because of the potential for social capital to mitigate HIV risk, some efforts have been made to explore whether social capital can be generated intentionally. Recent experiences from group-based microfinance projects in South Africa (Pronyk et al., 2008a, Pronyk et al., 2008c) and Kenya (Skovdal et al., 2010) suggest that social capital indeed can be generated and strengthened exogenously. Furthermore, we noted that many of the groups in Manicaland received assistance from non-governmental organisations and other external sources of support.

This study addresses an important gap in research on the effectiveness of social capital in reducing HIV vulnerability (Fisher and Thomas-Slayter, 2010) and found evidence for reductions in new cases of HIV infection amongst women who participated in community groups. Support for women’s community groups could be an effective HIV prevention strategy in countries with large-scale HIV epidemics. However, further studies are needed, in a wide range of settings, to compare levels of community group activity and associations with health outcomes, both measured on a consistent basis, to establish the generalisability of our findings, and to investigate the feasibility and effectiveness of generating social capital exogenously.

FIGURE 3. Ecological level effect of participation in community groups on adoption of lower risk sexual behaviour for women, Manicaland, Zimbabwe, 1998-2003.

NOTE: Adoption of lower risk sexual behaviour defined as decreasing or maintaining low risk behaviour where ‘decreased risk’ = reducing number of new sexual partners in the past year and ‘low risk’ = no new partners in the past year.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Wellcome Trust for financial support, the Manicaland Study team for assistance with data collection, and the people of Manicaland for their support and participation in the research.

References

- Albarracin D, Kumkale GT, Al E. Influences of social power and normative support on condom use decisions: a research synthesis. AIDS Care. 2004;16:700–723. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331269558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astone NM, Nathanson CA, Schoen R, Kim YJ. Family demograohy, social theory and investment in social capital. Population and Development Review. 1999;25:1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behaviour change. Psychological Review. 1977;84:191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker G, Ricardo C. Young men and the construction of maculinity in sub- Saharan Africa: implications for HIV/AIDS, conflict and violence. Washington D.C.: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Binagwaho A, Ratnayake N. The role of social capital in successful adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Africa. Public Library of Science Medicine. 2009;6:e18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke C, Maton K, Mankowski E, Anderson C. Healing men and community: predictors of outcome in a men’s initiatory and support organization. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2010;45:186–200. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9283-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C, Macphail C. Peer education, gender and the development of critical consciousness: Participatory HIV prevention by South African youth. Social Science and Medicine. 2002;55:331–345. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00289-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C, Mzaidume Z. Grassroots participation, peer education, and HIV prevention by sex workers in South Africa. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:1978–1987. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.12.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C, Nair Y, Maimane S. Building contexts that support effective community responses to HIV/AIDS: a South African case study. American Journal of Psychology. 2007;39:347–363. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C, Nair Y, Maimane S, Gibbs A. Strengthening community responses to AIDS: possibilities and challenges. In: Rohleder P, Swarz L, Kalichman S, editors. HIV/AIDS in South Africa 25 years on. Springer; London: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C, Williams B, Gilgen D. Is social capital a useful conceptual tool for exploring community level influences in HIV infection? An exploratory case study from South Africa. AIDS Care. 2002;14:41–54. doi: 10.1080/09540120220097928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu J, Grobbelaar J, Al E. HIV-related stigma and social capital in South Africa. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2008;20:519–530. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2008.20.6.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier P. Social Capital and Poverty. Washington D.C.; 1998. Social Capital Initiative Working Paper Number 4. [Google Scholar]

- Colvin C, Robins S. Positive men in hard, neoliberal times: engendering health citizenship in South Africa. In: Boeston J, Poku N, editors. Gender and HIV/AIDS: critical perspectives from the developing world. Ashgate Publishing Limited; Farnham: 2009. pp. 177–190. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby RA, Holtgrave DR, Al E. Social capital as a predictor of adolescents’ sexual risk behavior. AIDS and Behaviour. 2003;7:245–252. doi: 10.1023/a:1025439618581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta-Bergman MJ. An alternative approach to social capital: exploring the linkage between health consciousness and community participation. Health Communication. 2004;16:393–409. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1604_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson M, Dahlgren L, Al E. Social capital, gender and educational level - impact of self-rated health. The Open Public Health Journal. 2010;3:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher WF, Thomas-Slayter B. Mobilizing Social Capital in a World with AIDS. Worcester; MA, USA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Foley M, Edwards B. Is it time to divest in social capital? Journal of Public Policy. 1999;19:141–173. [Google Scholar]

- Folland S. Does “community social capital” contribute to population health? Social Science and Medicine. 2007;64:2342–2354. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregson S, Garnett GP, Nyamukapa CA, Hallett TB, Lewis JJC, Mason PR, Chandiwana SK, Anderson RM. HIV decline associated with behaviour change in eastern Zimbabwe. Science. 2006;311:664–666. doi: 10.1126/science.1121054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregson S, Gonese E, Hallett TB, Taruberekera N, Hargrove JW, Corbett EL, Dorrington R, Dube S, Dehne K-L, Mugurungi O. HIV decline due to reductions in risky sex in Zimbabwe? Evidence from a comprehensive epidemiological review. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2010;39:1311–1323. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregson S, Mushati P, White PR, Mlilo M, Mundandi C, Nyamukapa CA. Informal confidential voting interview methods and temporal changes in reported sexual risk behaviour for HIV transmission in sub-Saharan Africa. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2004a;80:36–42. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.012088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregson S, Nyamukapa CA, Lopman B, Mushati P, Garnett GP, Chandiwana SK, Anderson RM. A critique of early models of the demographic impact of HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa based on empirical data from Zimbabwe. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104:14586–14591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611540104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregson S, Nyamukapa CA, Schumacher C, Mugurungi O, Benedikt C, Mushati P, Campbell C, Garnett GP. Did national HIV prevention programmes contribute to HIV decline in eastern Zimbabwe? Evidence from a prospective community survey. Sexually Transmitted Infections. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182080877. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregson S, Terceira N, Mushati P, Nyamukapa CA, Campbell C. Community group participation: can it help young women to avoid HIV? An exploratory study of social capital and school education in rural Zimbabwe. Social Science and Medicine. 2004b;58:2119–2132. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregson S, Zhuwau T, Anderson R, Chandiwana S. Is there evidence for behaviour change in response to AIDS in rural Zimbabwe? Social Science and Medicine. 1998;46:321–330. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00165-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallett TB, Gregson S, Mugurungi O, Gonese E, Garnett GP. Is there evidence for behaviour change affecting the course of the HIV epidemic in Zimbabwe? A new mathematical modelling approach. Epidemics. 2009;1:108–117. doi: 10.1016/j.epidem.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halperin DT, Mugurungi O, Hallett TB, Muchini B, Campbell B, Magure T, Benedikt C, Gregson S. A surprising prevention success: Why did the HIV epidemic decline in Zimbabwe? Public Library of Science Medicine. 2011;8:e1000414. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawe P, Shiell A. Social capital and health promotion: a review. Social Science and Medicine. 2000;51:871–885. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtgrave DR, Crosby RA. Social capital, poverty, and income equality as predictors of gonorrhoea, syphilis, chlamydia and AIDS case rates in the United States. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2003;79:62–64. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.1.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Monetary Fund . World Economic Outlook Database. Washington DC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Subramanian S, Al E. Social capital and physical health. A systematic review of the literature. In: Kawachi I, Subramanian S, Kim D, editors. Social Capital and Health. Springer Science / Business Media LCC; New York: 2008. pp. 139–190. [Google Scholar]

- Lopman B, Nyamukapa CA, Mushati P, Wambe M, Mupambireyi Z, Mason PR, Garnett GP, Gregson S. Determinants of HIV incidence after 3 years follow-up in a cohort recruited between 1998 and 2000 in Manicaland, Zimbabwe. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;37:88–105. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyttleton C. Fleeing the fire: transformation and gendered belonging in Thai HIV/AIDS support groups. Medical Anthropology: Cross-Cultural Studies in Health and Illness. 2004;23:1–40. doi: 10.1080/01459740490275995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nhamo M, Campbell C, Gregson S. Contextual determinants of HIV prevention programme outcomes: obstacles to local-level AIDS competence in rural Zimbabwe. AIDS Care. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.521544. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris P, Inglehart R. Gendering social capital. Bowling in women’s leagues? In: O’neill B, Gidengil E, editors. Gender and Social Capital. Routledge; New York: 2006. pp. 73–98. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, Landolt P. The downside of social capital. The American Prospect. 1996;26:18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Pronyk PM, Harpman T, Al E. Can social capital be intentionally generated? A randomised trial from South Africa. Social Science and Medicine. 2008a;67:1559–1570. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pronyk PM, Harpman T, Al E. Is social capital associated with HIV risk in rural South Africa? Social Science and Medicine. 2008b;66:1999–2010. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pronyk PM, Kim J, Al E. A combined microfinance and training intervention can reduce HIV risk behaviour in young female participants. AIDS. 2008c;22:1659–1665. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328307a040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam R. Making Democracy Work. Princeton University Press; New Jersey: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam RD. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. Simon and Schuster; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ragnarsson A, Townsend L, Thorson A, Chopra M, Ekstraam AM. Social networks and concurrent sexual relationships - a qualitative study amongst men in an urban South African community. AIDS Care. 2009;21:1253–1258. doi: 10.1080/09540120902814361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saegart S, Thompson JP, Warren MR. Social capital in poor communities. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Skovdal M, Campbell C, Madanhire C, Mupambireyi Z, Nyamukapa CA, Gregson S. Masculinity as a barrier to men’s uptake of HIV services in Zimbabwe. Globalization and Health. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-7-13. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skovdal M, Mwasiaji W, Webale A, Tomkins AM. Building orphan competent communities: experiences from a community-based capital cash transfer initiative in Kenya. Health, Policy and Planning. 2010 doi: 10.1093/heapol/czq039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veenstra G. Social capital, SES, and health: an individual level analysis. Social Science and Medicine. 2000;50:619. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00307-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N. Powerlessness, empowerment and health: implications for health promotion programmes. American Journal of Health Promotion. 1992;6:197–205. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-6.3.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware NC, Idoko J, Al E. Explaining adherence success in sub-Saharan Africa: an ethnographic study. Public Library of Science Medicine. 2009;6:e1000011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolcock M. Microenterprise and social capital: a framework for theory, research and policy. Journal of Socio-Economics. 2001;30:193–198. [Google Scholar]

- Wouters E, Meulemans H, Van Rensburg HCJ. Slow to share: social capital and its role in public HIV disclosure among public sector ART patients in the Free State province of South Africa. AIDS Care. 2009;21:411–421. doi: 10.1080/09540120802242077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziersch AM, Baum FE. Involvement in civil society groups: is it good for your health? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2004;58:493–500. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.009084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimbabwe Ministry of Health and Child Welfare . Zimbabwe National HIV and AIDS Estimates 2009. Harare; 2010. [Google Scholar]