The National Institutes of Health (NIH) Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®) Roadmap initiative (www.nihpromis.org) is a cooperative research program designed to develop, evaluate, and standardize item banks to measure patient-reported outcomes (PROs) across different medical conditions as well as the US population (1). The goal of PROMIS is to develop reliable and valid item banks using item response theory (IRT) that can be administered in a variety of formats including short forms and computerized adaptive tests (CAT)(1-3). IRT is often referred to as “modern psychometric theory,” in contrast to “classic test theory,” or CTT. The basic idea behind both IRT and CTT is that there is some latent construct, or “trait,” underlying an illness experience. This construct cannot be directly measured, but can be indirectly measured by creating items that are scaled and scored. For example, “fatigue,” “pain,” “disability,” or even “happiness” are latent constructs, i.e. subjective feelings – we cannot take a picture, snap an X-Ray to view them, or run a blood test to check for them. However, we know they exist. People can experience more or less of these constructs, thus it is helpful to try to translate that experience into several levels represented by scores. IRT models the associations between items and the latent construct. Specifically, IRT models describe relationships between a respondent's underlying level on a construct and the probability of particular item responses.

Tests developed with CTT (such as the Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index(4), the Scleroderma Gastrointestinal Tract instrument(5)) require administering all items, even though only some are appropriate for the persons' trait level. Some items are too high for those with low trait levels (e.g., “can you walk 100 yards” to a patient in a wheelchair) or too low for those with high trait levels (e.g., “can you get up from the chair?” to a runner). In contrast, IRT methods make it possible to estimate person trait levels with any subset of items appropriate for the persons' trait levels in an item pool. As such, any set of items from the pool could be administered as a fixed form or, for greatest efficiency, administered as a CAT. CAT is an approach to administering the subset of items in an item bank that are most informative for measuring the health construct in order to achieve a target standard error of measurement. A good item bank will have items that represent a range of content and difficulty, provide high level of information, and have items that perform equivalently in different subgroups of the target population.

How does CAT work?

Without prior information, the first item administered in a CAT is typically one of medium trait level. For example, “In the past 7 days I was grouchy” with multi-level response from “never” to “always.” After each response, the person's trait level and associated standard error are estimated. The next item administered to someone not endorsing the first item, is an “easier” item. If the person endorses the first item, the next item administered is a “harder” item. CAT is terminated when the standard error falls below an acceptable value. This provides an estimate of one's score with the minimal number of questions and no loss of measurement precision. In addition, scores from different studies using different items can be compared using a common scale. IRT models estimate the underlying scale score (theta) from the items. All items are calibrated on the same metric and independently and collectively provide an estimate of theta. Hence, it is possible to estimate the score using any subset of items and to estimate the standard error of the estimated score. This allows assessment of health outcomes across patients with differing medical conditions (such as compare scores of someone with arthritis to someone with heart disease) at various degrees of physical and other impairments, both at the lowest and highest ends of trait levels.

PROMIS in Rheumatology

The life story of PROMIS tools

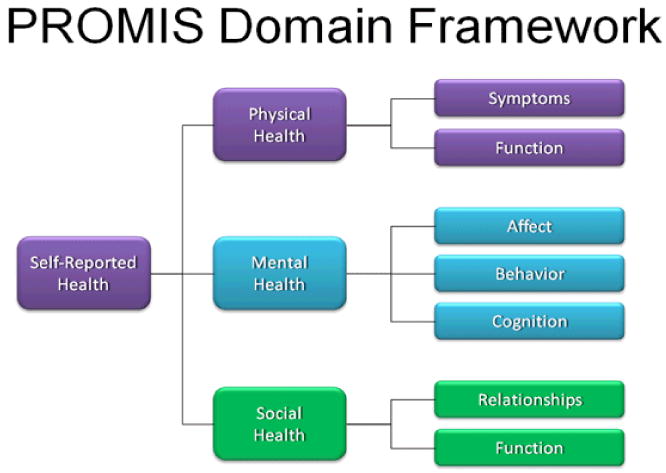

Since the beginning of PROMIS in 2004, much progress has been made in developing measures of self-reported health within a domain hierarchy (Figure 1). Physical functioning, fatigue, pain, emotional distress, and social health were the core domains of interest. While all these domains are relevant to rheumatic diseases, the physical health domain encompassed most of the traditionally important outcomes in rheumatology, such as physical function, pain, and fatigue.

Figure 1. PROMIS Domain hierarchy.

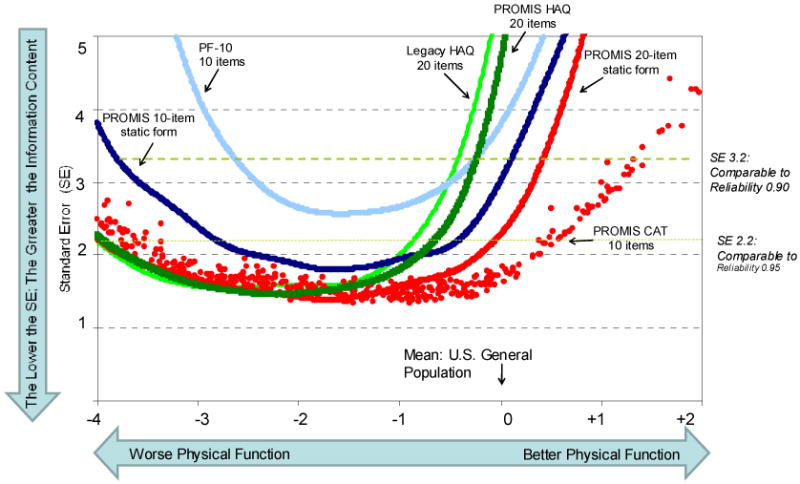

In PROMIS the term physical function was preferred over the term disability and represented the ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL) including instrumental (e.g., shopping) activities(6). The PROMIS physical function item bank containing 124 new items was developed from 1865 available items culled from 160 English language questionnaires. In addition to administering the item bank using CAT, PROMIS has developed several static short forms including: (1) a 20-item PROMIS HAQ, which corresponds to the HAQ-DI; (2) a PROMIS 10-item static, or short form with items selected as the “best” from the physical function items; and (3) a PROMIS 20-item static form also selected from the “best” PROMIS items. PROMIS- HAQ differs from HAQ-DI by deleting the one-week time frame and increasing the response option set from the original four choices to five by adding “with a little difficulty”. Measurement properties of different PROMIS item banks (PROMIS HAQ, PROMIS 10-item short form, PROMIS 20-item short form, and 10-item PROMIS CAT) were compared to the HAQ-DI and physical functioning 10-item (PF-10) scale of the SF-36 in 378 patients with rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, and normal aging cohorts(7). Instruments with greater information content have standard error curves that are lower and have a greater standard deviation (SD) range at a reliability > 0.95. PF-10 provided the least content information followed by HAQ-DI, which was better for patients with physical disability (SD≤ -1) but performed poorly for the average population (Figure 2). PROMIS items (10 or 20 items) performed better than PF-10 and HAQ-DI. The PROMIS CAT outperformed all the static items (Figure 2). The CAT maintained acceptable performance in populations whose physical function is 1.5 SD better than the population norm. This has implication for our patients as better treatments become available for rheumatic diseases we are likely to observe healthier cohorts of patients with arthritis. Thus, accurate assessment of those in the positive health range of physical functioning becomes increasingly important.

Figure 2.

Comparison of information content of 6 physical function instruments: HAQ-DI, PROMIS HAQ, PROMIS 10-item short form, PROMIS 20-item short form, PF-10 (from SF-36), and 10-item PROMIS CAT. Instruments with greater information content have standard error curves that are lower and have a greater SD range at a reliability > 0.95. More items are better than fewer, IRT-based (PROMIS) is better than non-IRT-based items and CAT is better than static. Taken from PMID 19738214

What PROMIS means for Rheumatology

Physical function, global health assessment and fatigue are important constructs in rheumatic diseases—in both adults and pediatrics. Availability of PROMIS tools will also catalyze research on the less well-studied impact of rheumatic diseases in all health domains. In the next sections, we discuss the advantages of PROMIS, its current use in rheumatology, and the future of PROMIS in rheumatology.

1. Advantages of PROMIS over traditional instruments

PROMIS employes a uniform qualitative process with detailed systematic review, focus groups, cognitive interviews, and translatability for each item bank. PROMIS has devoted substantive resources to ensuring that outcome measures are understood and usable by diverse populations. Items are written at a grade school level and tested for comprehensibility among low literacy populations. All items are reviewed and modified as needed for their translatability. To enhance inclusiveness, PROMIS informatics assessment tools are rendered accessible to populations with sensory limitations and others requiring assistive technology. Lastly, PROMIS measures are grounded in a life course perspective, as it is the group's ultimate goal to produce single metrics for the same domain across the full lifespan (i.e., PROMIS is linking measures developed for children with those developed for adults).

PROMIS instruments have been found to have better precision than existing measures; a quality that may lead to reduction in sample size in clinical studies(6). The severity of PROs in rheumatic diseases can be compared head-to head with other chronic conditions such as heart failure. It is possible to “customize” the set of items by selecting a set of items that are matched to the severity level of the target population. PROMIS items are currently available at no cost, enabling freer exchange of information and data, stimulating outcomes research.

Utilization of CAT to administer PROMIS items does require a computer that may limit its applicability in busy clinical practice. Although a person may receive different set of items from an item pool at each visit, users can track which items were administered in the CAT and track theta scores over time

2. Current PROMIS item banks and their validation in rheumatology

i. PROMIS item banks for adult patients

PROMIS item banks developed for adults including anger, anxiety, abilities and general concern, depression, fatigue, pain behavior, pain interference, physical function, positive and negative psychosocial impact of illness, sleep disturbance, sleep-impairment, satisfaction with participation in social roles, and satisfaction with participation in discretionary social activities are available at www.nihpromis.org. Additional short forms have been developed for constructs such as global health, global satisfaction with sex life, etc. All these item banks measure important constructs that are applicable to patients with arthritis and other rheumatologic conditions. As an example, the feasibility of 11 PROMIS item banks was recently assessed in a single center, observational study in patients with systemic sclerosis (SSc; scleroderma)(8). The average number of items completed for each CAT-administered item bank ranged from 5 to 8 (69 CAT items per patient), and the average time to complete each CAT-administered item bank ranged from 48 seconds to 1.9 minutes per patient (average time= 11.9 minutes/per patient for 11 banks). The time to complete the item banks was not significantly different in patients with physical disabilities (such as hand contractures and digital ulcers).

ii. PROMIS item banks for pediatric patients

PROMIS version 1.0 item banks and short forms developed for children include anger, anxiety, asthma impact, depressive symptoms, fatigue, pain interference, physical function (separate banks for upper extremity and mobility), and peer relationships, available at www.nihpromis.org.

The PROMIS Cooperative Network is currently in the process of evaluating the pediatric version 1.0 item banks in multiple pediatric chronic conditions including juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) and chronic musculoskeletal pain, widespread or regional. Importantly, the process includes a qualitative component including semi-structured interviews with children. Longitudinal validation in these pediatric conditions, among others, is underway.

iii. New PROMIS item banks under development

The PROMIS Cooperative Network has increased the focus and energy on development of pediatric item banks with 4 out of 12 of the PROMIS II sites (project period 2009-2012) dedicated to work in pediatrics. This includes development of new pediatric item banks to assess Pain Behavior, Pain Quality, Physical Activity, Subjective Well-Being, Experience of Stress and others, all of which are important in patients with chronic arthritis. Current efforts are also focused on linking adult and pediatric item banks measuring the same construct to allow measurement from childhood through adolescence then transition to adulthood on the same metric. The PROMIS Cooperative Network is also developing new item banks pertinent to chronic diseases. These include development of gastrointestinal symptoms items, self-efficacy for self-management of chronic illness, and others.

3. Future of PROMIS in rheumatology

The PROMIS mission is to use measurement science to create a state-of-the-art assessment system for self–reported health to advance PRO measurement in clinical research and day-to-day practice. Similar to other PRO's, this will facilitate the incorporation of the patient's voice into clinical trials and clinical practice. The American College of Rheumatology has endorsed the assessment of functional status in patients with rheumatoid arthritis at least every 12 months. For patients with JIA, it is recommended that functional status and health-related quality of life be assessed at 6 month intervals(9). This exacts new requirements of PRO measures, including exceptional ease of use, rapidity of administration, interpretability, and a clear benefit of using the data in patient-provider interactions and care management. We are a specialty well versed in the use of measures of disability, pain, and other aspects of health-related quality of life. PROMIS offers an opportunity for us to accelerate uptake and expand the use of PROs from research advocates to all clinicians.

Using PROMIS in Clinical Practice

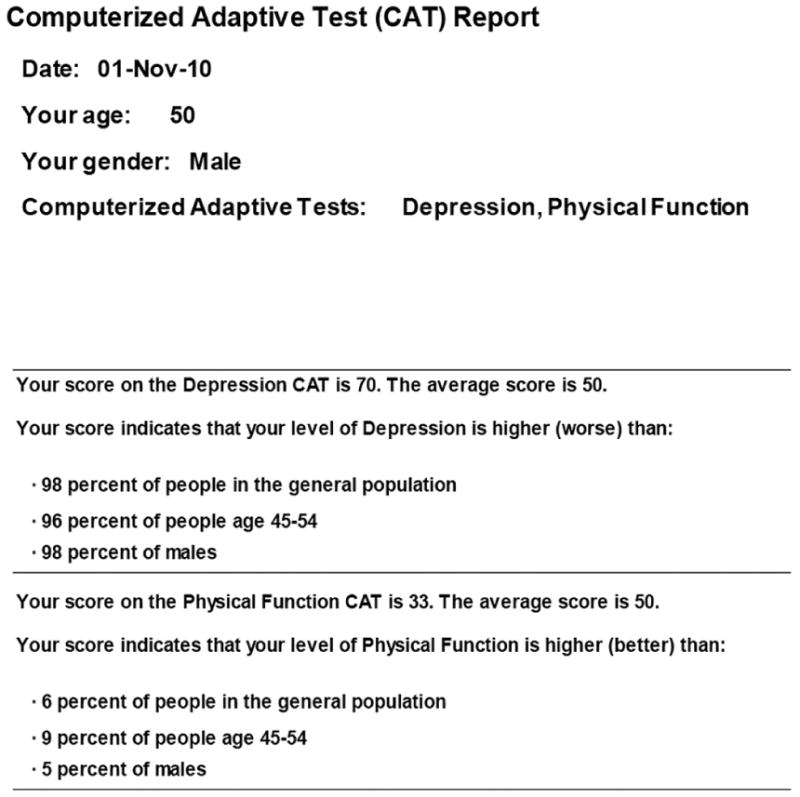

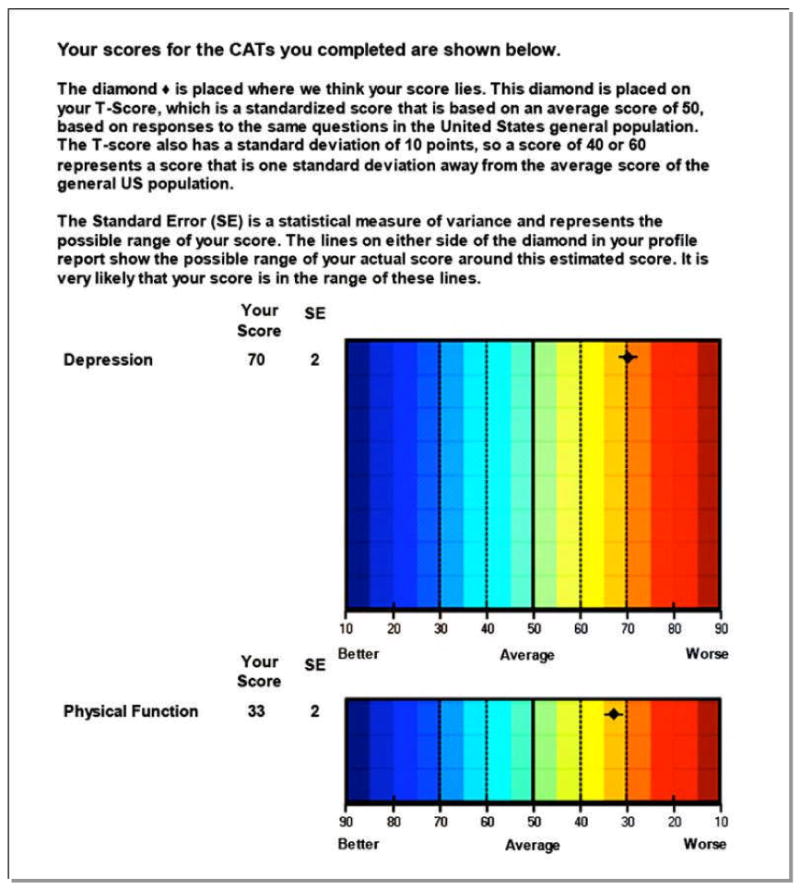

Being able to administer a choice of fatigue, pain interference, physical function, or depression measures, among many other options, in the waiting room on a Tablet, laptop, PC, and potentially a Smart Phone and have instant scoring, calibration to population norms and ready to share with the patient at point of care is compelling. As an example, Figures 3 and 4 show results from a 50 year old patient with early diffuse systemic sclerosis. This patient was administered CAT item banks for physical function and depression that took approximately 2 minutes to complete. The profile provides his current physical function (1.7 SD below US general population) and depression status (2 SD below US population). This information (presented in form of a PROMIS report in Figure 3 and a graph as shown in Figure 4) can be used for clinical care. This patient was referred for psychological counseling to help him adjust to his newly diagnosed systemic sclerosis and also prescribed physical therapy. The item banks can be administered at each clinic visit to assess change in symptoms from baseline visit. Current work is ongoing to assess the feasibility of incorporating PROMIS item banks in routine clinical practice.

Figure 3.

Computer generated PROMIS report of a 50-year old male with recently diagnosed systemic sclerosis. The report provides the patient's score for depression and physical function scales and compares it to the US general population.

Figure 4.

Computer generated PROMIS graph of a 50-year old male with recently diagnosed systemic sclerosis. The report depicts patient's score for depression and physical function scales and compares it to the US general population.

In conclusion, PROMIS has developed items banks that are relevant to rheumatology, can be “customized” to a patient or a practice, and are currently freely available. The item banks provide tremendous flexibility for creation of fixed length short-forms or CAT administration. This quick assessment can generate a patient report to monitor health over time.

Acknowledgments

D. Khanna, PP Khanna, B. Spiegel, and RD Hays were supported by a National Institutes of Health Award (NIH/NIAMS U01 AR057936A), the National Institutes of Health through the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research Grant (AR052177). E. Krishnan is supported by NIH/NAIMS 2U01 AR052158 E. Morgan DeWitt is supported National Institutes of Health Award (NIH/NIAMS U01AR057940). D. Khanna is also supported by NIH/NIAMS K23 AR053858-05). PP Khanna was also supported by Career Bridge Funding Award from the American College of Rheumatology. Hays was also supported by the UCLA Resource Center for Minority Aging Research/Center for Health Improvement in Minority Elderly (RCMAR/CHIME), NIH/NIA Grant Award Number P30AG021684, and the UCLA/ Drew Project EXPORT, NCMHD, 2P20MD000182

Reference List

- 1.Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, Gershon R, Cook K, Reeve B, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med Care. 2007;45(5 Suppl 1):S3–S11. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000258615.42478.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reeve BB, Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Cook KF, Crane PK, Teresi JA, et al. Psychometric evaluation and calibration of health-related quality of life item banks: plans for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Med Care. 2007;45(5 Suppl 1):S22–S31. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000250483.85507.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hays RD, Liu H, Spritzer K, Cella D. Item response theory analyses of physical functioning items in the medical outcomes study. Med Care. 2007;45(5 Suppl 1):S32–S38. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000246649.43232.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fries JF, Spitz P, Kraines RG, Holman HR. Measurement of patient outcome in arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23(2):137–145. doi: 10.1002/art.1780230202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khanna D, Hays RD, Maranian P, Seibold JR, Impens A, Mayes MD, et al. Reliability and validity of the University of California, Los Angeles Scleroderma Clinical Trial Consortium Gastrointestinal Tract Instrument. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(9):1257–1263. doi: 10.1002/art.24730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fries JF, Krishnan E, Bruce B. Items, Instruments, Crosswalks, and PROMIS. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(6):1093–1095. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fries JF, Cella D, Rose M, Krishnan E, Bruce B. Progress in assessing physical function in arthritis: PROMIS short forms and computerized adaptive testing. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(9):2061–2066. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khanna D, Rothrock N, Maranian P, Cella D, Gershon R, Khanna PP, et al. Feasibility and Evaluation of the Construct Validity of PROMIS and “Legacy” Instruments in an Academic Scleroderma Clinic. Value in Health. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.08.006. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lovell DJ, Passo MH, Beukelman T, Bowyer SL, Gottlieb BS, Henrickson M, et al. Measuring process of arthritis care: a proposed set of quality measures for the process of care in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63(1):10–16. doi: 10.1002/acr.20348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]