Abstract

The notion that apparent sizes are perceived relative to the size of one’s body is supported through the discovery of a new visual illusion. When graspable objects are magnified by wearing magnifying goggles, they appear to shrink back to near normal size when one’s hand (also magnified) is placed next to them. When objects are minified by wearing minifying goggles, the opposite occurs. However, this change in apparent size does not occur when familiar objects or someone else’s hand is placed next to the object. Presumably, objects’ apparent sizes shift closer to their actual size when the hand is viewed, because object sizes relative to the hand are the same with or without the magnifying/minifying goggles. These findings highlight the role of body scaling in size perception.

When perceiving the size of graspable objects, individuals use their dominant hand as a “perceptual ruler” with which to measure their apparent size. Consequently, the apparent sizes of graspable objects are scaled to the size of one’s dominant hand. Supporting this notion, we show, through the discovery of a new visual illusion, that an object’s size will appear to shrink or grow depending upon whether the viewer’s own hand can be simultaneously viewed. Specifically, when viewing an object while wearing magnification goggles, the placement of the viewer’s hand next to the object makes the object appear to shrink. Conversely, when wearing minification goggles, the viewer’s hand placement next to the object makes the object appear to grow. This illusion illustrates the important role of body-relative scaling in the perception of object size.

The relation between one’s body and the physical sizes of objects is crucial during the execution of actions as well as while determining what actions are possible. Several lines of research show that this relation may be the basis for the perceptual measurement of sizes and extents (Fajen, 2005; Witt, Proffitt & Epstein, 2005). According to this perspective, individuals likely perceive the sizes of graspable objects as a proportion of the maximum extent of their grasping ability in a given context (Linkenauger & Proffitt, 2007). So for example, the width of a soda bottle would appear smaller to someone with larger hands than it appears to an individual with small hands, because the soda bottle is a smaller proportion of the larger hands’ maximum grasp.

A well-know example of such body scaling of size can be seen in the movie, “Honey I Shrunk the Kids”, where a quirky scientist accidentally shrinks his children to the size of matchsticks with his newly invented shrinking machine. From the perspective of the shrunken children, their tiny backyard becomes a massive jungle, where a blade of grass appears to be the size of a tree. Interestingly, this example parallels the experience of those suffering from a neurological condition that sometimes accompanies chronic migraine syndrome, appropriately called “Alice in Wonderland” syndrome, wherein patients experience the growth (or shrinkage) of their body followed by the shrinkage (or growth) of the world around them (Todd, 1955). In both of these examples, the size of the physical world is perceived in relation to the real or apparent size of the perceiver’s body.

This relation between the body and perceived size can possibly be mapped onto neural mechanisms that combine proprioceptive and visual information. Single cell recording studies have found neurons that code for the relation of objects to the animal’s effectors. For example in macaque monkeys, neurons in the anterior intraparietal area (AIP) code for objects that are in grasping distance of the hand, regardless of the position of the hand or object in the visual field (Murata, Gallese, Luppino, Kaseda, & Sakata, 2000). Also, some neurons in this area code for the specific grasp required due to the shape and size of the object in addition to the position of the object relative to the hand (Murata et al., 2000, Taira, Mine, Georgopoulos, Murata, & Sakata, 1990). These cells also code for the orientation of the object relative to the orientation of the hand (Murata et al., 2000). In fact, when processing in the AIP is inhibited, the monkey’s ability to open its hand to an appropriate size to grasp a target is impaired (Gallese, Murata, Kaseda, Niki, & Sakata, 1994). Presumably, these neurons code for the ability to grasp a specific object, and are likely responsible for scaling visual information about the object to the body and its action capabilities.

In the current experiments, we explored size perception in conditions in which participants wore magnification or minification goggles. If perception is based on the relation between visual information and the body, and if only the target is magnified, then the optical-magnification will specify that the target is larger than it, in fact, is, and in turn, it will appear larger. However, if both the hand and target are viewed together under magnification, then the relative size relation between the hand and object is reestablished. Consequently, the target should not appear as magnified when the body is visually available as a reference, because the magnified target can be rescaled to the magnified body.

Previous studies have demonstrated handedness-related perceptual and behavioral effects in right-handed individuals who favor the right side of their body (Gonzalez, Ganel, & Goodale, 2006; Linkenauger, Witt, Bakdash, Stefanucci, & Proffitt, in press). Consistent with these fingings, we also hypothesized that hand dominance might influence the rescaling of objects size such that, for right handed people, the right hand acts as a more efficient “perceptual ruler” than does the left. Consequently, when viewing both the hand and the object under magnification, objects should be rescaled more and appear smaller when the right as opposed to the left hand is viewed next to the object.

Experiment 1: Magnification, Size Perception, and Hand Presence

Method

Participants

Forty-two (29 female) right-handed University of Virginia Students participated. Handedness was assessed using the Edinburgh Handedness Survey (M=93.74, SE = 1.59). All participants had normal or corrected to normal vision.

Design and Procedure

Participants were randomly assigned to either the dominant or non-dominant hand condition. In both conditions, participants sat at a uniformly white table while wearing goggles with magnifying lenses (30.5 cm focal length, 1.8 magnification). Participants were instructed to close their eyes while an object was placed on the table in front of them. Participants then made a verbal estimate of the apparent size of the object. Participants were instructed to make their verbal estimates using a 10 point scale in which 0 corresponded to the size of a pea and 10 corresponded to the size of a basketball. Participants were instructed to make these verbal estimates based on how big the object appeared rather that how big they thought the object actually was. Then the participants closed their eyes and another object was placed in front of them. Participants estimated the sizes of 6 objects, 3 objects that were familiar (baseball, 221 cm3, ping pong ball. 33 cm3, tennis ball, 144 cm3) and 3 objects that were unfamiliar (wooden circle, 57 cm3, wiffleball, 178 cm3, styrofoam ball, 113 cm3). After participants had made all 6 judgments, in the dominant condition, they were then instructed to perform another block of object size estimations with the same objects, except before making their verbal judgment, they were to place their dominant hands on the table beside the objects. In the non-dominant condition, participants placed their non-dominant hands on the table next to the object before making their verbal judgments.

Results and Discussion

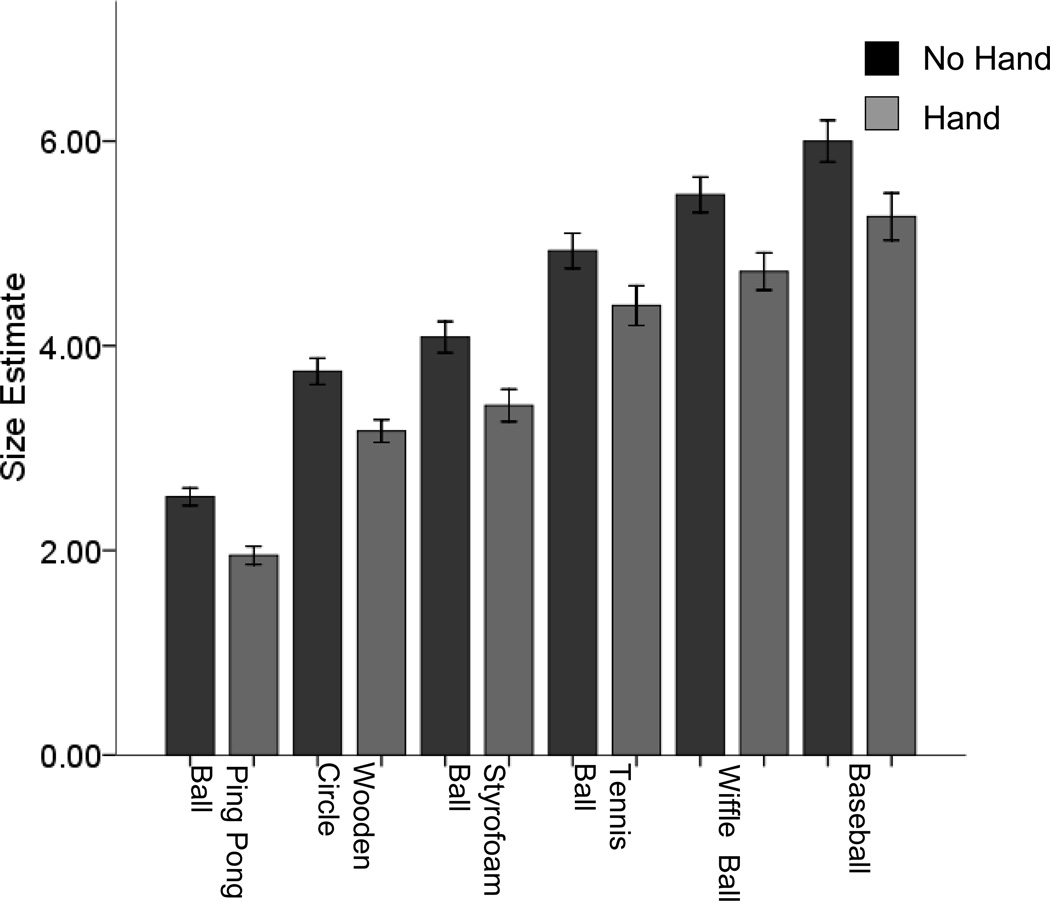

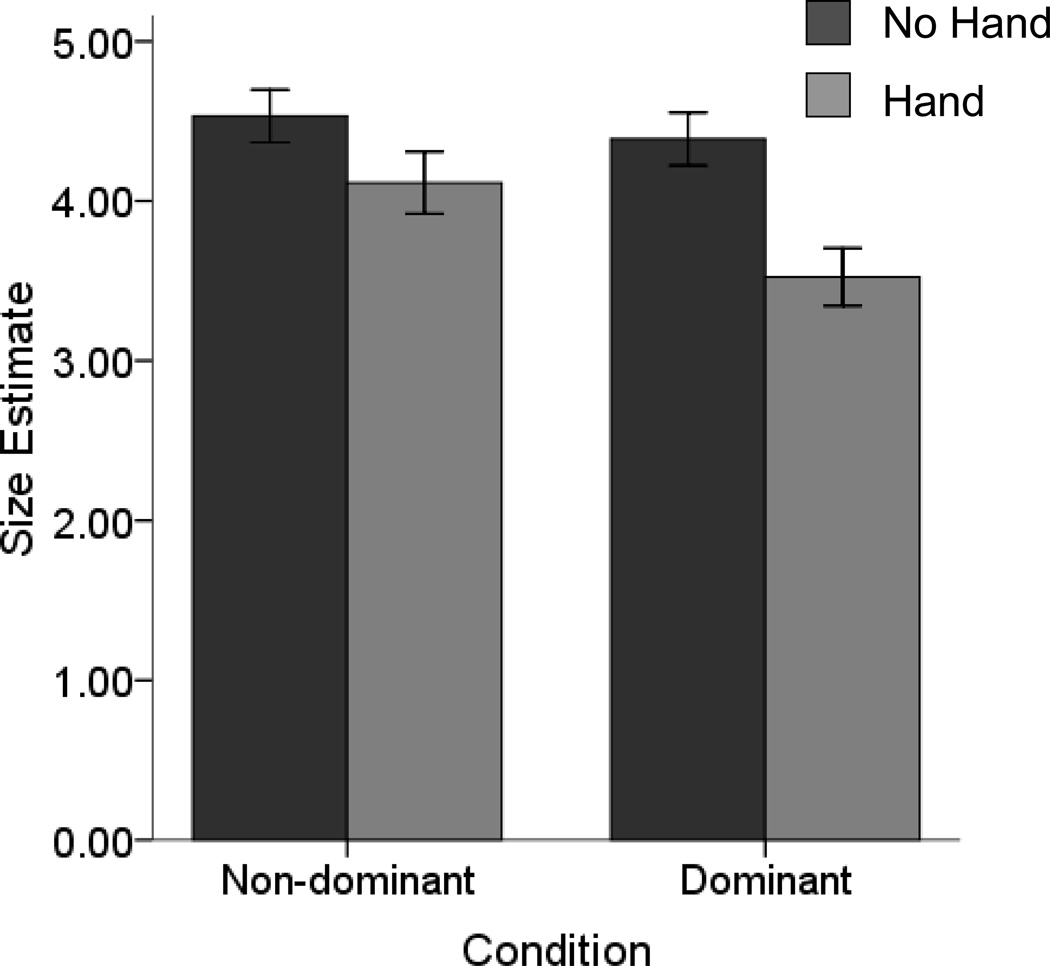

A 2 (hand presence) by 6 (object) repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with hand condition (dominant, non-dominant) as a between-subjects variable and with the verbal estimates as the dependent measure was performed. Overall, participants estimated the sizes of the objects to be smaller when their hand was present (M= 3.82, SE =.13) than when their hand was not present (M=4.39, SE =.12), F(1,40) = 33.75, prep >.99, ηp2 = .46, see Figure 1. In fact, many participants reported that the object appeared to “shrink” when they placed their hand next to the object. Object was also significant, with larger objects appearing larger, F(5,200) = 67.32, prep >.99, ηp2 = .85. There was no object by hand present interaction, prep<.50. As predicted, there was a significant hand condition by hand present interaction, F(1,40) = 4.12, prep = .88, ηp2 = .09, see Figure 2. This suggests that the apparent size of the object appeared to decrease more when participants first saw the object in the absence of their hand (M= 4.39., SE =.17) and then placed their dominant hand next to the object (M= 3.53., SE =.19) than when participants saw the object in the absence of their hand (M= 4.53., SE =.17) and then placed their non-dominant hand next to the object (M= 4.12., SE =.19).

Figure 1.

Size estimates with the hand placed next to the object and without the hand placed next to the object in Experiment 1. Error bars represent 1 standard error of the condition mean.

Figure 2.

Size estimates with and without the hand for the dominant and non-dominant hand from Experiment 1. Error bars represent 1 standard error of the condition mean.

Presumably, the object appeared less magnified when the hand was visible, even though the hand was just as magnified as the target objects, because apparent object size was rescaled to the magnified hand. Therefore, the relation between the target object and the hand was redefined to be the same as when viewed without the magnifying glasses making the object appear to be more similar to its unmagnified size. As signified by the lack of an object by hand preference interaction, this effect cannot be due to familiar size, because if familiar size played a role in the effect, then familiar objects such as the baseball, should not be as affected by hand presence as an unfamiliar object. Similarly, this result shows that the right hand is more efficient than the left at perceptually rescaling the sizes of objects.

Experiment 2: Minification, Size Perception, and Hand Presence

Methods

Participants

Twelve (6 female) University of Virginia students participated. All participants had normal or corrected to normal vision.

Design and Procedure

We repeated the same design as in Experiment 1 except that participants wore minifying goggles (inverted binoculars) instead of magnifying goggles, which made the surrounding environment appear smaller rather than larger. Also, participants only used their dominant hand. Verbal estimates were made in a similar fashion except that the scale was modified to accommodate smaller objects; 0 was the size of a pea and 10 was the size of a softball.

Results and Discussion

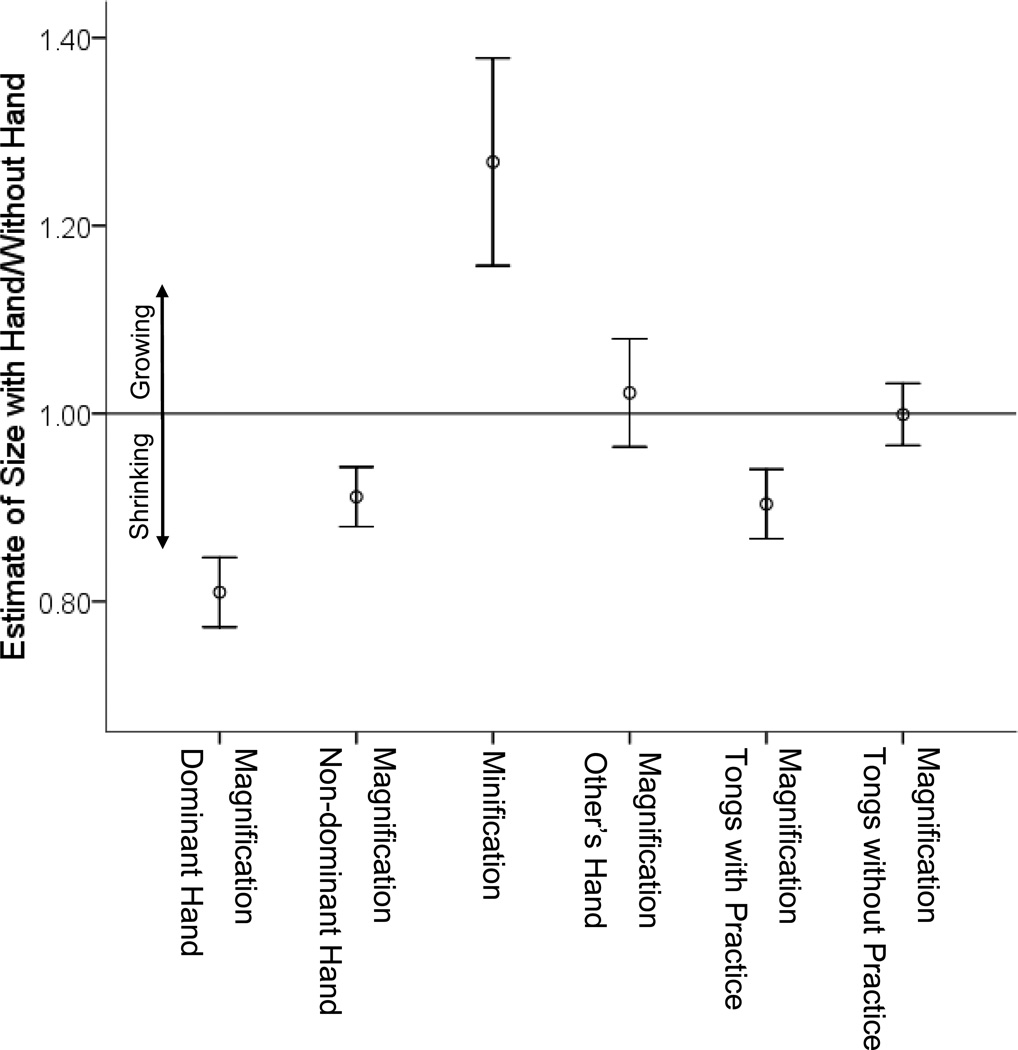

A 2 (hand presence) by 6 (object) ANOVA with the verbal estimates as the dependent measure was performed. Participants estimated the sizes of the objects to be larger when their hand was present (M=6.23, SE =.45) than when their hand was not present (M =5.08, SE =.36), F(1,11) = 8.17, prep =.94, ηp2 = 43, see Figure 3. Several participants commented that the target objects appeared to “grow” when they placed their hand next to the object, see Figure 1B. Object was also significant, with larger objects appearing larger, F(5,55) = 17.00, prep=.99, ηp2 = .43. There was no object by hand present interaction, prep=.81. Presumably, the apparent size of objects was rescaled when the hand was viewed, so that they appeared more similar to their unminified size. Both of these experiments demonstrate that perceived size is not independent of the body, but rather dependent on the body as a metric to scale (or rescale) apparent size.

Figure 3.

Size Estimates with the hand next to the objects divided by size estimates when without the hand next to the objects for each experimental condition. Error bars represent 1 standard error of the condition mean.

Experiment 3: Magnification, Object Size, and Another’s Hand

To expand on these findings, we investigated whether similar rescaling could occur when the perceiver viewed target objects in the presence of someone else’s hand.

Methods

Participants

Twelve (10 female) University of Virginia students participated. All participants had normal or corrected to normal vision.

Design and Procedure

We repeated the same design as in Experiment 1, but instead of the participants placing their hand beside the target objects, the research assistant’s hand was placed next to the target object prior to participants’ second set of verbal judgments.

Results and Discussion

A 2 (hand presence) by 6 (object) ANOVA with the verbal estimates as the dependent measure was performed. Participants estimated the objects to be the same size when a hand was present (M=4.06, SE =.17) and when a hand was not present (M =4.31, SE =.17), F(1,11) = 2.39, prep =.76. As expected, object size was significant, with larger objects appearing larger, F(5,55) = 53.53, prep>.99, ηp2 = .83. Surprisingly, participants size estimates did not differ depending on whether or not the research assistant’s hand was visible, see Figure 3, suggesting that this rescaling is contingent on viewing one’s own body rather than someone else’s.

Experiment 4: Magnification, Object Size, and Tool-Use

Several studies have reported that with practice, hand tools can become an extension of the body (Maravita, Husain, Clarke, & Driver, 2001; Berti & Frassinetti, 2000). Neurons that code for objects within reach will expand their receptive fields to include previously unreachable space that has been made reachable through tool-use (Iriki, Tanaka, & Iwamura, 1996), and neurons coding for hand centered space will expand their receptive fields to include space accounted for by a tool (Iriki, Tanaka, & Iwanmura, 1996). Inspired by these studies, we explored whether the perception of size could be based on the relation between the size of a tool and the target object.

Method

Participants

Twenty-four (12 female) University of Virginia students participated. All participants had normal or corrected to normal vision.

Design and Procedure

Upon entering, participants were randomly assigned into either the Practice or No Practice Condition. In the Practice condition, participants used a pair of kitchen tongs to transfer several different round objects from one box to another. Participants made a total of 40 lifts with the tongs. In the No Practice condition, participants were given no experience using the tongs. Participants in all conditions then put on the magnifying goggles and repeated the design used in Experiment 1. However, instead of placing their hand next to the objects, participants placed the tongs next to the objects. The hand holding the pair of tongs was occluded from view by a piece of white felt attached to the tongs which covered the hand.

Results and Discussion

For each condition, a 2 (hand presence) by 6 (object) ANOVA was performed with verbal estimates as the dependent measure. In the Practice condition, participants estimated the sizes of the objects to be smaller when the tongs were visible (M=3.67, SE =.19) than when the tongs were not visible (M =4.18, SE =.26), F(1,11) = 8.96, prep =.95, ηp2 = .45. Object size was significant, with larger objects appearing larger, F(5,55) = 53.57, prep>.99, ηp2 = .83. In the No Practice condition, participants estimated objects to be the same size when their tongs were visible (M=4.51, SE =.18) and when their tongs were not visible (M =4.56, SE =.25), F(1,11) = .096, prep <.50, see Figure 2. Object size was significant, with larger objects appearing larger, F(5,55) = 54.71, prep>.99, ηp2 = .83.

Participants who received tool-use training prior to performing the size estimation task, perceived the target objects as smaller when the tool was in view compared to when it was not, suggesting that they rescaled the size of the object to the tool. Alternatively, those who did not receive training with the tool did not perceive a change in the size of the target objects when simultaneously viewing the tool. These results support previous findings that tools become an extension of the body, but only after experience with their use.

Experiment 5: Magnification and Size Matching

In order to control for possible demand characteristics resulting from verbal reports, we thought it necessary to show the rescaling effect using a visual matching task.

Method

Participants

Ten right-handed students (7 female) from the University of Virginia participated. All participants had normal or corrected to normal vision.

Design and Procedure

We repeated the same design as in Experiment 1, but with a few exceptions. First, participants only viewed their dominant hand next to the objects. Secondly, participants made their size estimate by adjusting the size of a circle presented on a laptop screen so that it matched the size of the object. Participants adjusted the size of the circle on the laptop display by pressing arrow keys with their non-dominant hand on a wireless keyboard positioned on their lap below the table which was out of the participants’ sight. The laptop keyboard was covered by white felt so that it was not visible to the participants, and the screen was positioned on the table ~ 30 cm away from the left side of the participants.

Results and Discussion

A 2 (hand presence) by 6 (object) ANOVA with the size estimate diameters as the dependent measure was performed. As expected, hand present was significant with participants estimating the size of the object to be smaller when their hand was present (M= 5.14 cm, SE= .31 cm) than when their hand was not present (M=5.50 cm, SE= .35 cm), F(1,9) = 7.18, prep = .92, ηP2 = .44. Object size was also significant with larger objects being estimated as larger, F(5,45) = 7.18, prep > .99, ηp2 =.90. There was no object by size interaction, prep = .73. These findings show that the rescaling effect is generalizable to other estimates of apparent size.

Experiment 6: Magnification, Minification and Apparent Hand Size

In Experiment 1, we found that the right-hand acted as a more efficient perceptual ruler than the left hand. If this is the case, then the right hand should be less magnified (or minified) than the left when viewed by someone wearing magnifying goggles (or minifying goggles), because the right hand is the anchor (perceptual ruler) with which relative size is perceived. If the left hand is not used often (or less efficient) as a perceptual ruler, then it is typically not used as the anchor, and it should appear magnified (or minified) similarly to the target objects.

Method

Participants

Thirty-two right-handed (12 female) students from the University of Virginia participated. All participants had normal or corrected to normal vision.

Design and Procedure

Participants were randomly assigned into either the Magnifying condition or the Minifying condition. In the Magnifying condition, participants put on the magnifying glasses and were instructed to look at the sizes of their right and left hands (one at a time). After looking at both their right and left hands several times, participants responded whether their hands looked to be the same size or whether one hand looked larger than the other. If one hand looked larger, than they were asked to respond how much larger in percent the hand looked. In the Minifying condition, participants performed the same task except that they wore Minifying goggles rather than Magnifying goggles.

Results and Discussion

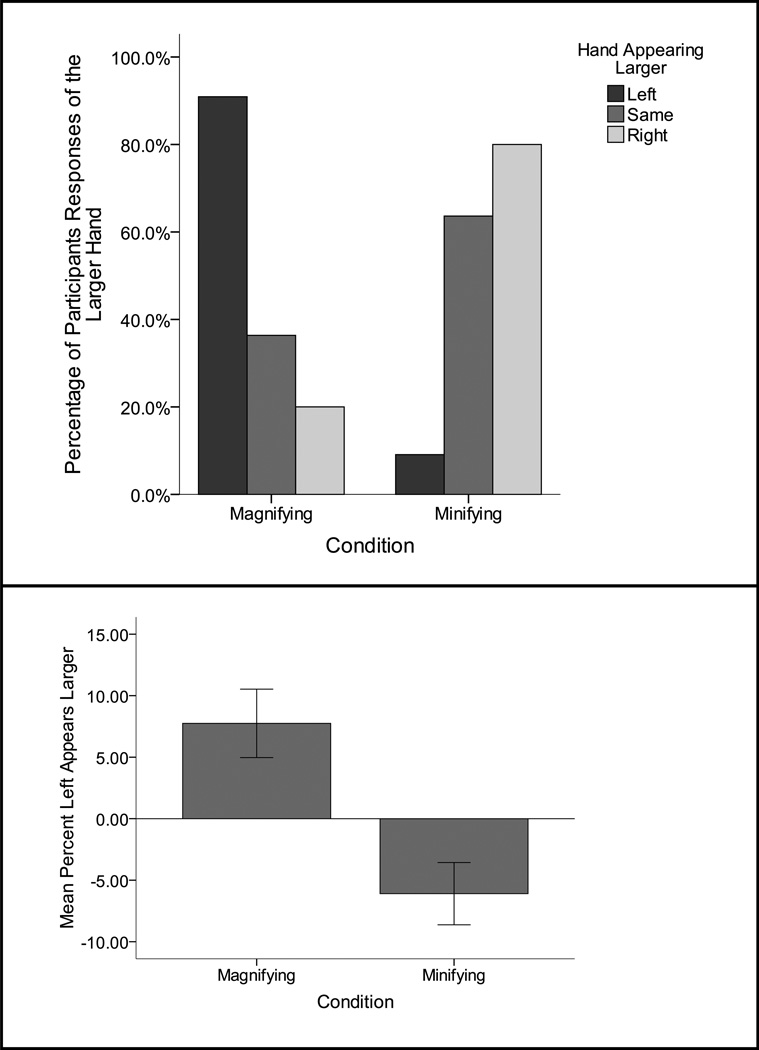

In the Magnification condition, 62.5% of the participants responded that their left hand appeared larger, 25% responded that both appeared to be the same size, and 12.5% responded that their right hand appeared larger. In the Minification condition, 6.25% of the participants responded that their left hand appeared larger, 44.75% responded that both appeared to be the same size, and 50% responded that their right hand appeared larger, see Figure 4A. Participants’ responses of how much larger one hand appeared than the other were coded in the following way. If participants responded that their right hand appeared larger, the percentage response of how much larger was coded as a negative value. If participants responded that both hands appeared the same size, than their response of how much larger was coded as zero. If participants responded that their left hand appeared larger, their percentage response of how much larger was coded as a positive value. Therefore, if the right hand appeared larger in a specific condition, then the mean response should be below zero. If the left hand appeared larger, then the mean response should be above zero. One-sample t-test, which tested the mean responses against zero, showed that those in the Magnifying condition responses indicated they saw their left hand as being larger (M=7.75, SE=2.78), t(15) = 2.79, prep = .94, two-tailed. Responses of those in the Minifying condition indicated that they saw their right hand as being larger (M=-6.09, SE=2.53), t(15) = -2.41, prep = .91, two-tailed. A independent samples t-test with condition as the independent variable and the percent response as the dependent variable showed that percent responses differed across the two conditions, t(30) = 3.68, prep = .99, two-tailed, ηp2 = .31, see Figure 4B. These data show that the right hand was less magnified when wearing magnifying goggles and less minified when wearing minifying goggles. Hence, this suggests that the right hand is the primary reference for apparent size scaling.

Figure 4.

(A) Percentage of participants’ responses of which hand appeared larger for the magnifying and minifying conditions. (B) Mean responses of how much larger the certain hand appeared in the magnification and minification conditions. Participants’ percentage responses that indicated a larger left hand were given a positive value. Participants that responded that their hands appeared the same were coded as zero, and participants’ percentage responses that indicated a larger right hand were coded as negative. Error bars represent 1 standard error of the condition mean.

General Discussion

Combined, these results show that the dominant hand, and to a lesser extent the non-dominant hand, are used to scale the apparent size of graspable objects. Additionally, a tool can also serve to scale apparent object size but only if one has experience with its use. These studies show that the body may serve as a metric with which to scale optical information specifying spatial layout. Because optical information comes to the eye in angular form – visual angles and ocular-motor adjustments, which are scaled as angles – this information needs to be rescaled into size-appropriate units. We propose that the perceptual system uses the body as a “perceptual ruler”, and thus, the sizes of graspable objects are perceived as a proportion of the hand’s size. This directly indicates to the perceiver how large objects are with respect to their hand’s grasping capabilities. Additional evidence for this perspective has shown that the distances to reachable objects are perceived as closer when people’s reaching ability is expanded by using a tool (Witt, Proffitt, & Epstein, 2005). This likely occurs because the “perceptual ruler”, defined by reaching ability, is expanded by tool use. Therefore, objects at the same physical distance are measured as closer on the stretched ruler. However, unlike previous studies, the experiments presented in this paper show a phenomenally noticeable change in size perception attributable to body scaling. Objects appeared to shrink or expand before the participants’ eyes.

Individuals’ have been shown to use familiar size as a cue to determine other objects’ sizes (Epstein, 1961, Epstein, 1965). Hence, it is possible that the change in size perception demonstrated in these studies could be due to people’s ability to scale objects sizes to any familiar object and not specifically to the body. There are multiple reasons why we think this is not the case. Firstly, we did use 3 objects with which most people are already familiar. If familiar size was used as a scaling cue, then placing the hand next to familiar objects should have resulted in a smaller effect (or no effect at all) than when placing the hand next to unfamiliar objects, because the familiar objects would have already been somewhat rescaled. However, there was no difference in the magnitude of the rescaling effect across familiar and unfamiliar objects. Secondly, an unknown person’s hand should suffice as a familiar size referent for scaling unfamiliar objects. Yet in this study, we found that participants’ did not rescale the size of the object to the research assistant’s hand, suggesting that one’s own body, or an extension thereof, is necessary for this rescaling rather another familiar object. Furthermore, perceiving the size of an unfamiliar object using a familiar sized object as a referent can be interpreted as an awareness of the relation between the physical size of a familiar object and the body, and in turn, as an indirect way of scaling to the body. Finally, people are familiar with the sizes of both of their hands, and yet, the first and final experiment showed that the dominant hand served more efficiently as a perceptual ruler and was less affected by optical magnification or minification compared to the non-dominant hand.

In order to have a perception of the world that supports our interaction with it, bodily information must be related to the visual angles that specify the spatial properties of the environment. We show here that, in the case of graspable objects, optical information is transformed and scaled to the dimensions of one’s hands, especially the dominant one. In summary, the dimensions of the body play the essential role of providing a perceptual ruler with which to scale the environment. To our knowledge, these are also the first experiments to demonstrate an observable change in the perception of an object’s size due to body-based scaling. Participants reported seeing objects shrink or expand as their hand came into view.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank William Epstein and Jonathan Bakdash for their comments and revisions on earlier versions of the manuscript. This research has been supported by NIH Grant RO1MH075781to the second author.

Contributor Information

Sally A. Linkenauger, Department of Psychology; University of Virginia.

Veronica Ramenzoni, University of Virginia.

Dennis R. Proffitt, Department of Psychology; University of Virginia.

References

- Berti A, Frassinetti F. When far becomes near: Remapping of space by tool- use. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2000;12 doi: 10.1162/089892900562237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein W. The known-size-apparent-distance hypothesis. The American Journal of Psychology. 1961;74 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein W. Non-relational judgments of size and distance. The American Journal of Psychology. 1965;78 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fajen B. Perceiving possibilities for action: On the necessity of calibration and perceptual learning for the visual guidance of action. Perception. 2005;34 doi: 10.1068/p5405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallese V, Murata A, Kaseda M, Niki N, Sakata H. Deficit of hand preshaping after muscimol injection in monkey parietal cortex. Neuroreport. 1994;5 doi: 10.1097/00001756-199407000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez C, Ganel T, Goodale M. Hemispheric specialization for the visual control of action is independent of handedness. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2006;95 doi: 10.1152/jn.01187.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iriki A, Tanaka M, Iwamura Y. Coding of modified body schema during tool use by macaque postcentral neurons. Neuroreport. 1996;7 doi: 10.1097/00001756-199610020-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linkenauger SA, Proffitt DR. The effect of intention and body capabilities on the perception of size. Journal of Vision. 2008;8(6):620, 620a. http://journalofvision.org/8/6/620/ [Google Scholar]

- Linkenauger SA, Witt JK, Bakdash JZ, Stefanucci JK, Proffitt DR. Asymmetrical Body Perception: A possible role for neural body representations. Psychological Science. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02447.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maravita A, Husain M, Clarke K, Driver J. Reaching with a tool extents visual-tactile interactions into far space: Evidence from cross modal extinction. Neuropsychologia. 2001;39 doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(00)00150-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata A, Gallese V, Luppino G, Kaseda M, Sakata H. Selectivity for the shape, size, and orientation of objects for grasping in neurons of monkey parietal area AIP. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2000;83 doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.5.2580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taira M, Mine S, Georgopoulos A, Murata A, Sakata H. Parietal cortex neurons of the monkey related to the visual guidance of hand movement. Experimental Brain Research. 1990;83 doi: 10.1007/BF00232190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd J. The syndrome of Alice in Wonderland. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1955;73 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt JK, Proffitt DR, Epstein W. Tool-use affects perception, but only when you intend to use it. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 2005;31 doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.31.5.880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]