Abstract

Renal ammonia metabolism is the predominant component of net acid excretion and new bicarbonate generation. Renal ammonia metabolism is regulated by acid-base balance. Both acute and chronic acid loads enhance ammonia production in the proximal tubule and secretion into the urine. In contrast, alkalosis reduces ammoniagenesis. Hypokalemia is a common electrolyte disorder that significantly increases renal ammonia production and excretion, despite causing metabolic alkalosis. Although the net effects of hypokalemia are similar to metabolic acidosis, molecular mechanisms of renal ammonia production and transport have not been well understood. This mini review summarizes recent findings regarding renal ammonia metabolism in response to chronic hypokalemia.

Keywords: kidney, ammonia, acids, hypokalemia

Introduction

Urinary excretion of ammonia accounts for the largest portion of net acid excretion and thereby plays a critical role in acid-base homeostasis1-5). Renal ammonia excretion involves intrarenal ammoniagenesis and renal epithelial transport, rather than the glomerular filtration4, 5). Ammonia excreted into the urine is linked to production of new bicarbonate and results in net acid excretion. Ammonia that is not excreted in the urine is returned to the systemic circulation and metabolized in the liver to produce urea via a process that consumes bicarbonate.

Ammoniagenesis in the proximal tubule

Although all nephron segments can produce ammonia, the proximal tubule is the most important site of renal ammoniagenesis4, 5). Production of ammonia occurs predominantly from the cellular metabolism of glutamine, a major circulating amino acid. Glutamine is transported into renal proximal tubule across the basolateral membrane via the glutamine transporter SN16).

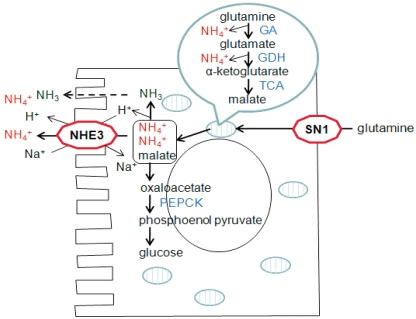

Glutamine is subsequently transported into the mitochondria and then is metabolized into glutamate and NH4+ by glutaminase7). Deamination of glutamate yields α-ketoglutarate and an additional NH4+ by glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) in mitochondria8). Further metabolism of α-ketoglutarate produces malate, which is then transported to the cytoplasm from the mitochondria. Malate is converted to oxaloacetate and finally to phosphoenolpyruvate and carbon dioxide by phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK)9, 10). Therefore, complete metabolism of glutamine yields two NH4+ ions in the proximal tubule (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Ammonia Metabolism in the Proximal Tubule. GA, glutaminase; GDH, glutamine dehydrogenase; TCA, tricarboxylic acid cycle enzymes; PEPCK, phosphoenol pyruvate carboxykinase.

Ammonia transport along the nephron segments

Ammonia produced in the proximal tubule is secreted to the lumen fluid by both NH3 diffusion and NH4+ transport through the action of the apical Na+/H+ exchanger (NHE-3) (Fig. 1). About 20% of ammonia produced in the proximal tubule also passes the basolateral membrane by substitution of NH4+ ions for K+ and reaches the renal venous blood.

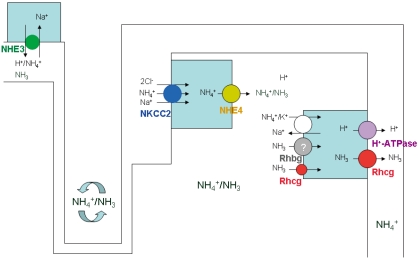

Luminal NH4+ travels down and then is reabsorbed in the thick ascending limb into the medullary interstitium. The apical Na+-K+(NH4+)-2Cl- cotransporter 2 (NKCC2) and basolateral Na+-H+(NH4+) exchanger 4 (NHE4) play a critical role in the ammonia transport in the thick ascending limb11, 12). Recent studies by Bourgeois et al. demonstrated that mice lacking NHE4 exhibited inappropriate urinary ammonia excretion and reduced ammonia medulla content12). NH4+ dissociates into NH3 and H+ generating a corticomedullary NH3 (and NH4+) gradient in the medullary interstitium.

The collecting duct then finally secretes ammonia into urine4, 5, 13). Although collecting duct NH3 transport was initially thought to involve diffusive NH3 movement across plasma membranes, recent studies have shown that Rh glycoproteins, Rhbg and Rhcg, play important roles in collecting duct ammonia secretion5, 13-17) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Schematic Representation of the Ammonia Transport Mechanisms along the Nephron Segments. NHE3, Na+/H+ exchanger; NKCC2, Na+-K+(NH4+)-2Cl-cotransporter 2; NHE4, Na+-H+(NH4+) exchanger 4.

Ammonia production and transport in response to acidosis

Metabolic acidosis stimulates ammonia production and transport by renal epithelial cells. Acidosis stimulates glutamine uptake into the proximal tubule and upregulates the expression of ammonia-producing enzymes, glutaminase, GDH, and PEPCK6, 7, 9, 10). Metabolic acidosis also increases the apical NHE3 activity and protein abundance in the proximal tubule18).

As mentioned earlier, ammonia reabsorption in the thick ascending limb leads to medullary interstitial ammonia accumulation, thereby driving its secretion into the collecting duct. Metabolic acidosis stimulated NKCC2 mRNA and protein expression in the rat and increased NHE4 mRNA expression in mouse thick ascending limb cells11, 12).

Rh B Glycoprotein (Rhbg) and Rh C Glycoprotein (Rhcg) are recently recognized ammonia transporter family members. Chronic HCl ingestion increased Rhcg protein expression and altered its subcellular distribution in the collecting duct19, 20). Both global and collecting duct-specific Rhcg knockout mice excreted less urinary ammonia under basal conditions and developed more severe metabolic acidosis after acid loading21, 22).

Ammonia production and transport in response to hypokalemia

Ammonia production and excretion into urine are also regulated by potassium balance. Hypokalemia increases renal ammonia production in experimental animals and humans, whereas hyperkalemia decreases renal ammonia production8, 23, 24). Renal ammonia metabolism in response to hypokalemia has not been well understood, because there is increased ammonia excretion despite the development of metabolic alkalosis.

Similar to metabolic acidosis, hypokalemia induces increased glutamine uptake into the proximal tubule and increased expression of the key ammoniagenic enzymes, glutaminase, GDH and PEPCK8, 25). Rats with hypokalemia had a marked increase in renal NHE3 abundance26).

However, in contrast to the metabolic acidosis, hypokalemia downregulated NKCC2 protein expression and NHE4 mRNA expression remained unchanged26, 27).

In the collecting duct, there is increased expression of Rh glycoprotein, Rhcg, in response to hypokalemia16). If Rhcg expression is associated with systemic acid-base homeostasis, hypokalemia should decrease its expression due to the development of alkalosis. These observations indicate that the enhanced Rhcg expression and collecting duct ammonia excretion could be regulated through mechanisms independent of acid-base homeostasis.

The stimulation of ammoniagenesis in response to acidosis or hypokalemia is likely to be activated by either intracellular acidic pH or other factors. Recent studies have also demonstrated that the increase in urinary ammonia excretion even developed within 2 days of potassium deprivation, when the plasma potassium level was within normal limits8).

Table 1 summarizes the expression of renal producing enzymes and transporters in response to metabolic acidosis and hypokalemia.

Table 1.

Expression of Renal Ammoniagenic Enzymes and Epithelial Transporters in Response to Metabolic Acidosis and Hypokalemia

GA, glutaminase; GDH, glutamine dehydrogenase; PEPCK, phosphoenol pyruvate carboxykinase; NHE3, Na+/H+ exchanger; NKCC2, Na+-K+(NH4+)-2Cl--cotransporter 2; NHE4, Na+-H+(NH4+) exchanger 4.

Conclusion

Both metabolic acidosis and hypokalemia are associated with increased ammoniagenesis and urinary ammonia excretion. Both acidosis and hypokalemia stimulates glutamine uptake and the expression of ammoniagenic enzymes in the proximal tubule. Expression of NKCC2 and NHE4 differ in response to acidosis and hypokalemia. Both acidosis and hypokalemia stimulate Rhcg expression in the collecting duct, but the regulation mechanisms may be different from each other.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the KOSEF (2009-0073733, 2011-0016068) grant.

References

- 1.Alper SL, Natale J, Gluck S, Lodish HF, Brown D. Subtypes of intercalated cells in rat kidney collecting duct defined by antibodies against erythroid band 3 and renal vacuolar H+-ATPase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:5429–5433. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.14.5429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim J, Kim YH, Cha JH, Tisher CC, Madsen KM. Intercalated cell subtypes in connecting tubule and cortical collecting duct of rat and mouse. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:1–12. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knepper MA, Packer R, Good DW. Ammonium transport in the kidney. Physiol Rev. 1989;69:179–249. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1989.69.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiner ID. The Rh gene family and renal ammonium transport. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2004;13:533–540. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200409000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiner ID, Verlander JW. Role of NH3 and NH4+ transporters in renal acid-base transport. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011;300:F11–F23. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00554.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solbu TT, Boulland JL, Zahid W, et al. Induction and targeting of the glutamine transporter SN1 to the basolateral membranes of cortical kidney tubule cells during chronic metabolic acidosis suggest a role in pH regulation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:869–877. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004060433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tong J, Harrison G, Curthoys NP. The effect of metabolic acidosis on the synthesis and turnover of rat renal phosphate-dependent glutaminase. Biochem J. 1986;233:139–144. doi: 10.1042/bj2330139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abu Hossain S, Chaudhry FA, Zahedi K, Siddiqui F, Amlal H. Cellular and molecular basis of increased ammoniagenesis in potassium deprivation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011;301:F969–F978. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00010.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alleyne GA, Scullard GH. Renal metabolic response to acid base changes. I. Enzymatic control of ammoniagenesis in the rat. J Clin Invest. 1969;48:364–370. doi: 10.1172/JCI105993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vinay P, Allignet E, Pichette C, Watford M, Lemieux G, Gougoux A. Changes in renal metabolite profile and ammoniagenesis during acute and chronic metabolic acidosis in dog and rat. Kidney Int. 1980;17:312–325. doi: 10.1038/ki.1980.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Attmane-Elakeb A, Mount DB, Sibella V, Vernimmen C, Hebert SC, Bichara M. Stimulation by in vivo and in vitro metabolic acidosis of expression of rBSC-1, the Na+-K+(NH4+)-2Cl- cotransporter of the rat medullary thick ascending limb. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33681–33691. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bourgeois S, Meer LV, Wootla B, et al. NHE4 is critical for the renal handling of ammonia in rodents. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1895–1904. doi: 10.1172/JCI36581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagner CA, Devuyst O, Belge H, Bourgeois S, Houillier P. The rhesus protein RhCG: a new perspective in ammonium transport and distal urinary acidification. Kidney Int. 2011;79:154–161. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eladari D, Cheval L, Quentin F, et al. Expression of RhCG, a new putative NH3/NH4+ transporter, along the rat nephron. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1999–2008. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000025280.02386.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han KH, Croker BP, Clapp WL, et al. Expression of the ammonia transporter, rh C glycoprotein, in normal and neoplastic human kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2670–2679. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006020160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han KH, Lee HW, Handlogten ME, et al. Effect of hypokalemia on renal expression of the ammonia transporter family members, Rh B Glycoprotein and Rh C Glycoprotein, in the rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011;301:F823–F832. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00266.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verlander JW, Miller RT, Frank AE, Royaux IE, Kim YH, Weiner ID. Localization of the ammonium transporter proteins RhBG and RhCG in mouse kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;284:F323–F337. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00050.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ambuhl PM, Amemiya M, Danczkay M, et al. Chronic metabolic acidosis increases NHE3 protein abundance in rat kidney. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:F917–F925. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.271.4.F917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seshadri RM, Klein JD, Kozlowski S, et al. Renal expression of the ammonia transporters, Rhbg and Rhcg, in response to chronic metabolic acidosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;290:F397–F408. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00162.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seshadri RM, Klein JD, Smith T, et al. Changes in subcellular distribution of the ammonia transporter, Rhcg, in response to chronic metabolic acidosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;290:F1443–F1452. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00459.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biver S, Belge H, Bourgeois S, et al. A role for Rhesus factor Rhcg in renal ammonium excretion and male fertility. Nature. 2008;456:339–343. doi: 10.1038/nature07518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee HW, Verlander JW, Bishop JM, Igarashi P, Handlogten ME, Weiner ID. Collecting duct-specific Rh C glycoprotein deletion alters basal and acidosis-stimulated renal ammonia excretion. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;296:F1364–F1375. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90667.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karet FE. Mechanisms in hyperkalemic renal tubular acidosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:251–254. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008020166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tannen RL. Effect of potassium on renal acidification and acid-base homeostasis. Semin Nephrol. 1987;7:263–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tizianello A, Garibotto G, Robaudo C, et al. Renal ammoniagenesis in humans with chronic potassium depletion. Kidney Int. 1991;40:772–778. doi: 10.1038/ki.1991.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elkjaer ML, Kwon TH, Wang W, et al. Altered expression of renal NHE3, TSC, BSC-1, and ENaC subunits in potassium-depleted rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002;283:F1376–F1388. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00186.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Z, Baird N, Shumaker H, Soleimani M. Potassium depletion and acid-base transporters in rat kidney: differential effect of hypophysectomy. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:F736–F743. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1997.272.6.F736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]