Abstract

Background

Neurocognitive impairment remains prevalent in HIV infected (HIV+) individuals despite highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART). We assessed the impact of HIV, HAART, and aging using structural neuroimaging.

Methods

Seventy-eight participants (HIV− (n=26), HIV+ on stable HAART (HIV+/HAART+; n=26), HIV+ naive to HAART (HIV+/HAART−; n=26)) completed neuroimaging and neuropsychological testing. A subset of HIV+ subjects (n = 12) performed longitudinal assessments before and after initiating HAART. Neuropsychological tests evaluated memory, psychomotor speed, and executive function and a composite neuropsychological score was calculated based on normalized performances (NPZ-4). Volumetrics were evaluated for the amygdala, caudate, thalamus, hippocampus, putamen, corpus callosum, cerebral grey and white matter. A three-group one way analysis of variance assessed differences in neuroimaging and neuropsychological indices. Correlations were examined between NPZ-4 and volumetrics. Exploratory testing using a broken stick regression model evaluated self-reported duration of HIV infection on brain structure.

Results

HIV+ individuals had significant reductions in brain volumetrics within select subcortical regions (amygdala, caudate, and corpus callosum) compared to HIV− participants. However, HAART did not affect brain structure as regional volumes were similar for HIV+/HAART− and HIV+/HAART+. No association existed between NPZ-4 and volumetrics. HIV and aging were independently associated with volumetric reductions. Exploratory analyses suggest caudate atrophy due to HIV slowly occurs after self-reported seroconversion.

Conclusions

HIV associated volumetric reductions within the amygdala, caudate, and corpus callosum occurs despite HAART. A gradual decline in caudate volume occurs after self-reported seroconversion. HIV and aging independently increase brain vulnerability. Additional longitudinal structural MRI studies, especially within older HIV+ participants, are required.

Keywords: HIV, HAART, aging, brain volume

INTRODUCTION

Prior to the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the life expectancy of HIV infected (HIV+) participants was less than ten years after initial diagnosis 1. The introduction of HAART has prolonged the lives of HIV+ participants with many living for more than twenty years after seroconversion. As a result, more HIV+ individuals are reaching advanced ages 2. If current trends continue more than fifty percent of all HIV+ participants in the United States will be greater than fifty years old by 2015 3. Older HIV+ participants may be at increased risk for accelerated body aging 4–7. Similar changes could occur in the brain 8–10. Given the importance of brain function to overall clinical outcomes and HAART compliance, it is critical that sensitive indicators of possible brain disruption are discovered.

Brain volumetric measures may represent a robust method for quantifying brain integrity in the presence of HIV 11. Brain atrophy has been well-described since the early discovery of the virus. Many pre-HAART studies demonstrated HIV associated losses within subcortical regions 12–15. The degree of atrophy due to HIV has been shown to correlate with poorer neuropsychological performance16–19.

Despite the introduction of HAART, changes in brain structure have persisted within impaired and cognitively normal HIV+ individuals 17, 20–23. More recent studies in the HAART era have demonstrated HIV associated brain atrophy occurs not only within subcortical areas, but also cortical regions 17, 21, 24, 25 However, most of the studies have primarily focused on HIV+ participants on stable therapy (~80% of any cohort) 10, 17, 20–25 rather than HIV+ participants naïve to medications.

Historically brain atrophy within HIV+ patients has been attributed to direct or indirect effects of the virus, yet growing concerns exist over possible neurotoxic risks associated with long-term administration of HAART 26, 27. Cell culture studies have demonstrated neuronal loss after the introduction of HAART 28, 29. In humans, neuropsychological performance improved in a large cohort of HIV+ participants after discontinuing HAART 30 or after participating in a drug holiday 31. In particular, efavirenz may be neurotoxic as a higher prevalence of HAND has been observed in HIV+ individuals taking this medication 32. A recent neuroimaging study has also demonstrated a reduction in neuronal function in HIV+ participants after initiating HAART 33. These findings suggest a need to further investigate the potential side-effects of HAART on brain structure.

Given the continued prevalence of HAND despite HAART, isolating additional factors that might influence brain integrity will be crucial for determining if and when neuroprotective interventions should be administered. The aim of this study was to determine the effects of HIV, HAART, and aging on subcortical and cortical brain volumetric measures. We hypothesized that HIV, and to a lesser extent HAART, is associated with structural atrophy. We additionally predicted that HIV and aging would each independently relate to reductions in brain volumetric measures. Results from the study could support the use of structural neuroimaging as a possible tool for differentiating the impact of HIV from other factors associated with loss of brain integrity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants and Laboratory Testing

Seventy-eight participants provided written consent approved by the Institutional Review Board at Washington University in Saint Louis. Individuals with a history of confounding neurological disorders including epilepsy, stroke, head injury resulting in a loss of consciousness greater than 30 minutes, major psychiatric disorders, or active substance abuse were excluded. Serological status of all HIV+ participants was confirmed by documented positive HIV enzyme-linked immunoassay and Western blot or detection of plasma HIV RNA by polymerase chain reaction. All HIV+ participants had laboratory evaluations (plasma CD4 cell count and HIV viral load (VL)). The cohort was divided into three groups: HIV− subjects (n=26), HIV+ individuals on a stable HAART regimen for at least 3 months prior to imaging (HIV+/HAART+; n=26), and HIV+ participants naive to HAART (HIV+/HAART−; n=26). In addition, a subgroup of the HIV+/HAART− (n=12) were longitudinally assessed immediately prior to starting medications and ~6 months after being on a stable therapy (Supplemental Figure 1).

Neuropsychological Evaluation

A standard neuropsychological performance battery (including Trail-Making Tests A & B, the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised, and the Digit-Symbol Modalities Test (WAIS-III R)) was administered to participants. These tests examine memory, psychomotor speed, and executive function and have been previously used to briefly assess HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder 31, 34. Raw scores from each test were standardized using demographic (age, gender, race, education) adjusted normative means 35. A standardized z-score was calculated by subtracting the appropriate normative mean from the raw score and then dividing by the normative standard deviation. A composite neuropsychological summary Z-score (NPZ-4) was calculated by averaging z-scores from each test. For longitudinal assessments, alternate forms of the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised were administered. These different versions ensured that subjects were not influenced by previous exposure.

Medications

The specific regimens that HIV+/HAART+ participants (n=26) received included 14 nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) + non-NRTIs (NNRITs), 11 NRTIs+ protease inhibitors (PIs), or 1 NRTIs only. The longitudinal subgroup of HIV+ participants (n=12) were followed before and after receiving the following either 7 NRTIs + NNRITs or 5 NRTIs+ PIs. The ability of a particular antiretroviral (ARV) medication to penetrate across the blood brain barrier has been classified using a central penetration effectiveness (CPE) score 36. The score for each ARV in a HIV+ participant’s regimen was summed and a total CPE was calculated for a particular regimen.

Imaging

Scanning was performed using a 3T Siemens Tim TRIO whole-body magnetic resonance scanner (Siemens AG, Erlangen, Germany) with a product transmit/receive head coil. Structural imaging were acquired using a T1-weighted three dimensional magnetization-prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo (MPRAGE) sequence (Time of repetition (TR)/echo time (TE)/inversion time (TI)/ = 2400/3.16 /1000/milliseconds, flip angle = 8°, 162 slices, and voxel size = 1 × 1 × 1 mm3). Images were visually inspected at the scanner with an additional scan performed if significant movement was observed.

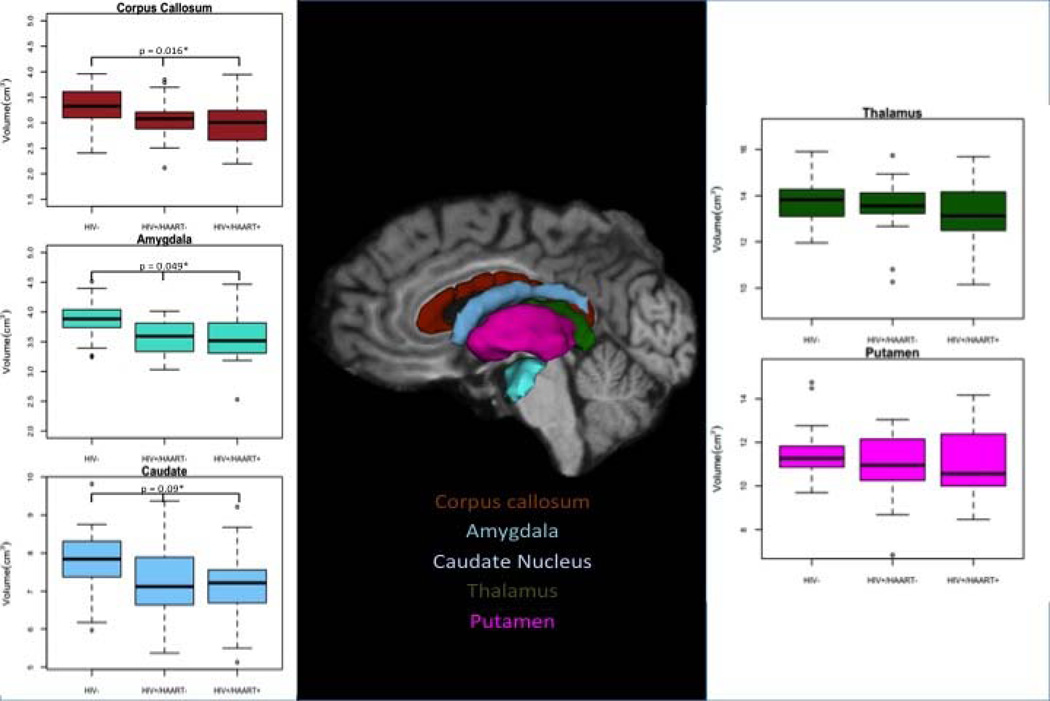

A general automated processing stream was performed using a previously described software package (Freesurfer Version 4.5 (2008) developed at the Martinos Center, Harvard University, Boston, MA; http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu) 37, 38. Briefly, MPRAGE scans were transformed into a format compatible for Freesurfer. Brain segmentation was accomplished with voxel intensity normalization applied to remove magnetic resonance bias. Skull stripping was performed to remove surrounding tissue. The brain was subsequently registered to a template volume in Talairach space. Based on prior probabilities of voxel identity assigned by the Freesurfer atlas 39 subcortical and cortical volumes were subsequently delineated 38. The quality of segmentation was independently confirmed by two reviewers extensively trained in Freesurfer processing (M.O. and J.H.). Segmented volumes were manually edited only when outliers were identified. Once corrected these scans were reanalyzed 40. Using a least squares residual regression model normalized values were obtained from six bilaterally selected regions of interest 41 (ROIs). These ROIs included the amygdala, caudate, thalamus, hippocampus, and putamen (Figure 1). The total corpus callosum value was obtained by summing the posterior, posterior-middle, middle, anterior-middle, and anterior portions. In addition, total cerebral cortex, grey matter, and white matter volumes were determined. For the subgroup that was assessed before and after starting HAART, the longitudinal option of the Freesurfer 4.5 pipeline was utilized.

Figure 1.

Using Freesurfer the corpus callosum, amygdala, caudate, thalamus, and putamen were determined for each subject. * Denotes the p-value for brain regions that were significantly different after a one-way analysis of variance (correcting for multiple comparisons). All error bars are presented as quartiles.

Statistical Analysis

Cross-sectional analysis

Brain volumetric values were transformed to the natural logarithmic scale in order to improve the normality of distribution and to facilitate the interpretation of the results. The differences among groups on the logarithmic scale were then suitably transformed and reported in terms of proportional differences of mean volume among groups. The logarithm transformation allowed for comparisons of relative differences across brain regions. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was first conducted for each of the brain regions, comparing the three groups: HIV−, HIV+/HAART−, and HIV+/HAART+. The p-values for the nine ANOVAs were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Hochberg algorithm 42. Volumes that showed a significant difference at the 0.10 level were considered for further assessment. The exploratory nature of the study justified using this less strict level of selection. In particular, three ROIs were subsequently studied.

Within these three ROIs a linear model analysis was performed to investigate the difference in the log volumes between groups. These analyses were adjusted for age and/or sex, if these variables were significant at a p < 0.20. Among the HIV+ subjects (HIV+/HAART− and HIV+/HAART+), the association between laboratory values (current CD4 cell count, nadir CD4 cell count, log10 plasma HIV VL) and brain volumetric measures were assessed via simple linear regression models. However, for duration of infection we also controlled for age, in order to detect any effects of HIV infection in addition to natural aging

Longitudinal analysis

In a subgroup of HIV+/HAART− participants, structural imaging was performed immediately prior to starting medications as well as at ~6 months after the subject was successfully on a stable ARV regimen. Brain volumetric measures for each of the above ROIs, laboratory values, and NPZ-4 scores were compared for the two time points using simple paired t-tests. In addition to main effects of HIV and age, an interaction between HIV and age on brain volume was included if significant at the 0.05 level.

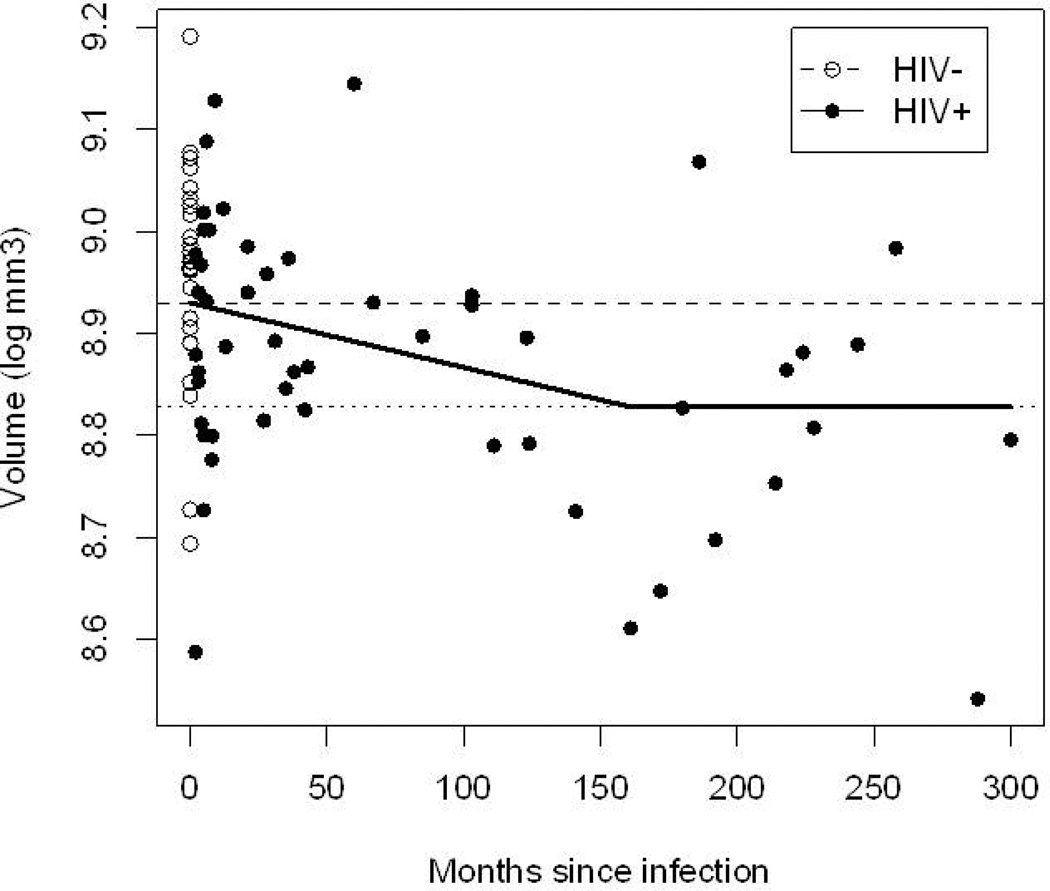

Effects of age

For the caudate where both age and HIV effects were observed, an exploratory analysis was performed investigating the hypothesis that the HIV effect develops gradually, from no effect at the time of infection, to a steady-state effect, after a certain period of time. In this scenario, the effect of HIV infection on the brain region acts in two stages: stage 1 is a transition stage, in which brain loss is gradual, from the uninfected levels to the long-term infected volumes. Stage 2 is the steady-state situation, in which the effect of HIV translates into a constant reduction in brain volume. At this stage the impact of HIV is in addition to the natural aging process. To this end, we used cross-sectional data, using self-reported duration of infection (di). The HIV− group was included with di=0, i.e., as a surrogate for subjects just prior to infection. This is a natural exploratory hypothesis and model, since it is hard to conceive that the difference in brain volumes between the HIV+ and HIV− subjects would occur immediately. For additional clarity we included a smooth estimation of brain volumes. Accordingly, first, a non-parametric lowess smoother 43 was used to explore the effect of time since infection on brain volumes for HIV+ subjects only. Secondly, the HIV effect was estimated using a “broken stick” (or piecewise linear) regression model 44, in which the transition stage between time 0 and T has a linear effect on the log-brain volume, and the steady-state, from T onwards, where the effect of HIV infection is constant. T was the time required for the brain volume at seroconversion to transition to the level of a chronic HIV infection. For this analysis the effect of self-reported duration of infection (D) on the log-volume was equal to: zero if D = 0 (i.e., for HIV− subjects), βD if 0<D<T, and βT if D≥T. As a consequence, βT was the age-adjusted difference in mean response between the HIV− and the chronically infected HIV+ group. The coefficient β was determined from the regression model. The breakpoint T, representing self-reported duration of transition time associated with atrophy due to HIV, was determined through a grid search that used a maximum likelihood. A 95% confidence interval for T was calculated via parametric bootstrap. In order to determine the line of best fit, a more gradual change in brain volume was compared to abrupt brain atrophy by the Akaike information criterion (AIC) 45. All analyses were performed using R statistical software (version 2.10.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

HIV+ participants performed worse on neuropsychological performance testing than HIV−

Cross sectional demographic variables for the three groups (HIV−, HIV+/HAART−, and HIV+/HAART+) are shown in Table 1. No significant differences were noted among the groups in regard to age, sex, or education. In general, the HIV+ subjects performed poorly on neuropsychological performance testing compared to HIV− (p=0.02). This difference was primarily driven by the HIV+/HAART− group who had worse NPZ-4 scores than HIV− (p=0.03) but who were not different from the HIV+/HAART+ (p=0.09). Differences between HIV+/HAART+ and HIV+/HAART− included self-reported duration of disease with HIV+/HAART+ participants infected for a significantly longer time period. The two HIV+ groups also differed on HIV markers (CD4 nadir, CD4 current, and log10 plasma HIV VL). The HIV+/HAART+ subjects had a significantly lower nadir and a higher current CD4 cell count. Log10 plasma HIV VL was significantly lower in HIV+/HAART+ group with more than three quarters of these participants having an undetectable value (< 50 copies/mL). These results likely reflect successful reconstitution with ARVs. The average CPE score for the HIV+/HAART+ participants was 7 with regimens chosen by health practitioner in conjunction with patient preferences.

Table 1.

Demographic, medical, neuropsychological, and laboratory values for all subjects. All errors are reported as standard deviation of the mean, and quartiles for laboratory values.

| HIV− (n= 26) |

HIV+/HAART− (n=26) |

HIV+/HAART+ (n=26) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Mean age (years old) | 34 ± 11 | 37 ± 13 | 40 ± 12 | 0.27 |

| Education (years) | 14 ± 3 | 13 ± 2 | 13 ± 2 | 0.14 |

| Sex (% Male) | 77 | 92 | 85 | 0.13 |

| Medical and Neuropsychological | ||||

| Duration of HIV Infection (months) | NA | 36 ±69 | 126 ±89 | <0.001 |

| Duration on HAART(months) | NA | NA | 66 ± 78 | NA |

| Central Nervous System Penetration Effectiveness Score (CPE) | NA | NA | 7.0 ± 0.4 | NA |

| NPZ-4 score | −0.03 ± .19 | −0.76 ±.20 | −0.16 ± .19 | 0.02 |

| Laboratory | ||||

| Median CD4 (cells/µL) (Quartiles) | NA | 363 (198,429) | 462 (353,771) | 0.004 |

| Median CD4 nadir (cells/µL) (Quartiles) | NA | 287 (195,403) | 193 (52, 377) | 0.003 |

| Median Log Plasma Viral Load (copies) (Quartiles) | NA | 3.51(3.51, 5.06) | 1.69 (1.69, 1.81) | <0.001 |

| % Virologically Suppressed (<50 copies/ mL) | NA | NA | 77 | NA |

Brain volumes from select regions were reduced in HIV+ individuals

Brain volumetric measures were obtained from the ROIs (Figure 1). Only three ROIs were significantly different (amygdala, corpus callosum, and caudate) among the groups (adjusted p-values = 0.016, 0.049, 0.090 respectively). For the three ROIs HIV+/HAART− and HIV+/HAART+ participants had significantly smaller volumetric measures compared to HIV−. HAART did not affect brain structure as volumetric measures for each of the regions were similar for HIV+/HAART− and HIV+/HAART+. The total cerebral cortex volume as well as grey and white matter volumes was similar among the groups (Supplemental Table 1).

Changes in brain volumetrics did not correlate with typical laboratory markers of HIV disease

For the HIV+ groups the relationship between known markers of HIV disease and volumetric measures were also assessed. No significant correlations existed between volumetric measures within the three ROIs and either current CD4 cell count or CD4 nadir cell count. HIV VL was correlated with caudate volume for HIV+/HAART+ participants (p=0.001). However, these results were primarily weighted by six HIV+/HAART+ participants who had escaped viral suppression (< 50 copies/mL) despite being on HAART. If these subjects were removed from the analysis then no significant differences were seen. In addition, no significant correlations existed between log10 plasma HIV VL and brain volumetric measures for HIV+/HAART− subjects. In regards to neuropsychological performance, no significant correlations existed between NPZ-4 scores and volumetric measurements for each of the three regions (all p > 0.30).

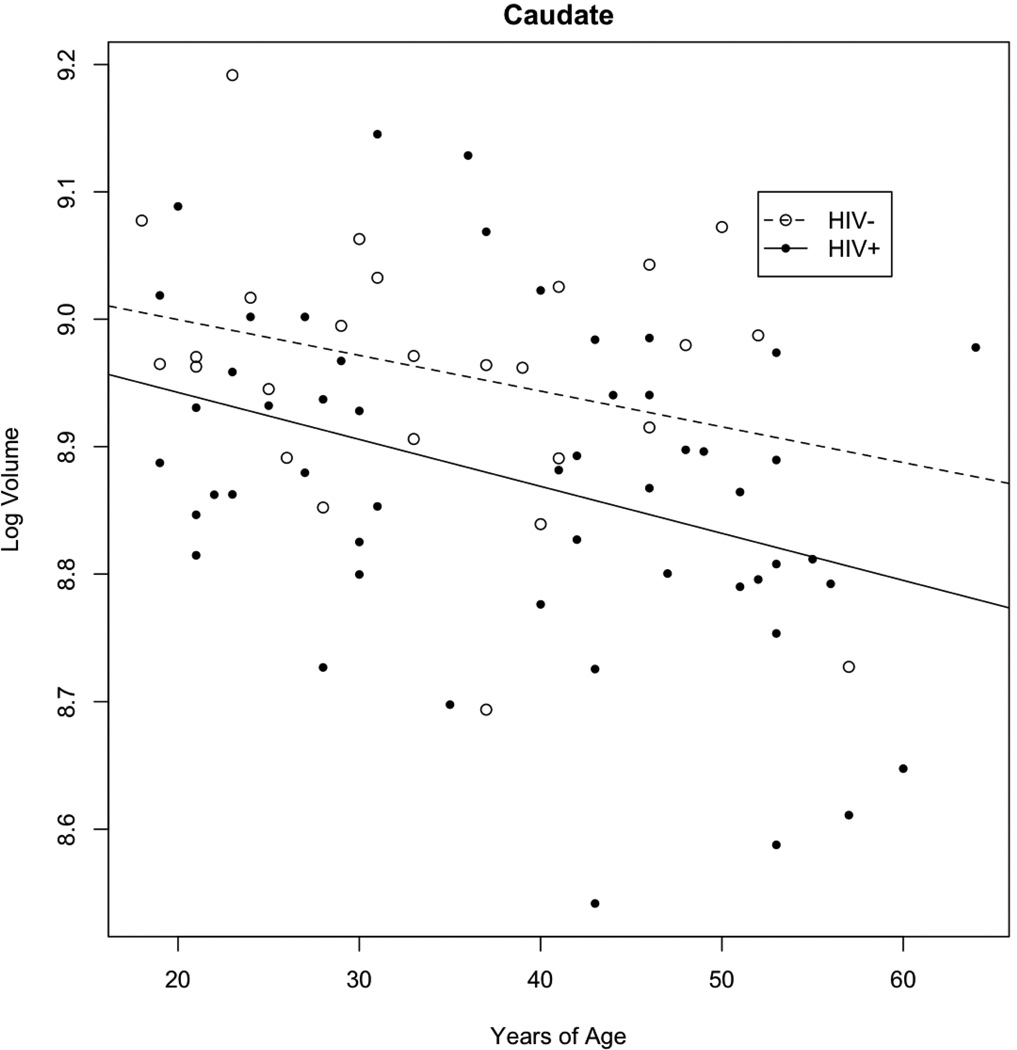

Brain volumetric measures were inversely correlated with age in HIV+ participants

A decrease in caudate volume was seen with increasing age for the three groups. Since HIV+/HAART− and HIV+/HAART+ participants had similar results (data not shown), these two groups were combined into a single group (HIV+) and compared to HIV− subjects (Figure 2). Both increasing age and HIV infection were each associated with significant decreases in caudate volume but no significant interaction was present. For every 10 years, HIV led to a 6% decrease in caudate volume while aging resulted in a 4% decrease (Table 2). Overall for a given age, caudate volumetric values in a HIV+ subject were equivalent to a HIV− participant who was approximately 17 year older. For the amygdala and the corpus callosum significant effects of HIV but not aging were observed. No significant age by HIV interactions were seen within these two regions (Table 2).

Figure 2. Effects of HIV and aging within the caudate.

For both HIV+ and HIV− subjects a significant reduction in caudate volume was seen with aging. Overall HIV+ participants had a greater atrophy than HIV−. For this analysis, HIV+/HAART+ and HIV+/HAART− were combined into a single group as similar results were seen for the two subgroups.

Table 2. Effects of HIV and aging on select regions of interest.

An effect of HIV was seen within each of these regions. Only within the caudate was there an effect of HIV and aging. No interaction was seen between HIV and aging in the three regions.

| Difference (95% CI) | Cohen’s d (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAUDATE | |||

| HIV effect | −6.1% (−11.2, −0.7)% | 0.55 (0.06, 1.05) | 0.028 |

| Age effect (per 10 years) | −3.6% (−5.6, −1.5)% | 0.32 (0.13, 0.51) | 0.001 |

| HIV & Age interaction | 0.62 | ||

| AMYGDALA | |||

| HIV effect | −6.8% (−10.9, −2.6)% | 0.78 (0.29, 1.27) | 0.002 |

| Age effect (per 10 years) | −1.2% (−2.9, 0.5)% | 0.14 (0, 0.33) | 0.15 |

| HIV & Age interaction | 0.21 | ||

| CORPUS CALLOSUM | |||

| HIV effect | −8.2% (−13.9, −2.2)% | 0.66 (0.17, 1.15) | 0.009 |

| Age effect (per 10 years) | −0.7% (−3.1, 1.8)% | 0.05 (0, 0.24) | 0.57 |

| HIV & Age interaction | 0.091 |

HAART does not change brain volumetrics

Within the subset of the HIV+/HAART− that started medications, neuroimaging was performed both before and after starting HAART. The introduction of HAART led to a significant reduction in log10 plasma HIV VL (p<0.001) and an increase in CD4 cell count (p=0.03) (data not shown). However, there was no change in volumetric measures within select ROIs (i.e. caudate) after starting HAART (Supplemental Figure 2). Some improvements on neuropsychological performance testing were seen at the second assessment, but this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.65). For each of the ROIs there was no significant effect of self-reported duration of HAART on brain volume (data not shown).

Caudate volume atrophies after ~ 13-years of HIV infection

The difference in brain volume between the HIV+ and HIV− subjects suggests that following the time of self-reported infection certain regions may be at increased risk for atrophy. Based on an exploratory model that uses the “broken stick” method, the estimated time (T) needed for the brain volume to transition from self-reported date of HIV+ infection to HIV-the level of seen for chronically HIV+ infection was 161 months (13.4 years), 95% CI (3–300 months) (Figure 3). While a significant degree of variability was observed, a more gradual decline in brain volume fit the data better than a one implying abrupt atrophy (improvement in AIC = 0.57).

Figure 3. Effects of self-reported duration of HIV infection on caudate volume.

HIV− are represented at T=0. This group can be seen as subjects just prior to HIV infection. The upper hashed line is the mean log volume for HIV−. The lower dotted line is the mean log-volume for chronically infected HIV. The dashed smooth line (lowess) and the solid broken-stick line (piecewise linear model) show the progression of caudate atrophy from the HIV− status to the chronically infected HIV+ status. Approximately 160 months (~13 years) is required for this transition. A large amount of variability exists. All lines were age-adjusted.

DISCUSSION

HIV is associated with a significant reduction in volume within select subcortical regions including the amygdala, caudate, and corpus callosum. A reduction in brain volumetrics was seen for HIV+ participants regardless of the presence or absence of HAART. Observed changes in brain volume due to HIV infection were independent of aging. Our results suggest that HIV+ individuals continue to have volumetric loss even in the HAART era.

Changes in brain volume due to HIV were primarily seen within subcortical areas such as the amygdala, caudate, and corpus callosum. Observed changes correspond with previous volumetric studies that showed significant decreases in particular subcortical regions such as the caudate, amygdala, and hippocampus 9, 10, 20, 21, 23. Changes have also been previously noted within the corpus callosum using volumetrics 21, 46. In contrast other subcortical areas such as the thalamus, putamen, or parahippocampus were not affected 17, 24, 25. The precise reason why specific subcortical areas are affected remains unknown, but may reflect the close proximity of these structures to the ventricles 47. This proximity may allow for easier viral penetration by HIV−infected mononuclear cells trafficking into the brain as well as increased HIV toxic products, such as gp120 and Tat 48–50. In particular, the highest concentrations of HIV have been observed in the corpus callosum and caudate compared to other brain regions 20, 48, 51. Our results suggest that pathological changes continue to persist, primarily in subcortical regions, despite HAART 11.

In this analysis we observed no significant differences in total cerebral cortex, grey matter or white matter volume for HIV+ participants compared to HIV−. A number of studies have observed a decrease in grey matter due to HIV infection 17, 20, 24, 52 while others also observed no significant changes 12, 53–56. Discrepancies between the various studies may be due to differences in the degree of impairment in HIV+ participants as well as the inclusion of matched HIV−.

Interestingly within the HIV+ participants similar volumetric values were observed for HIV+/HAART+ and HIV+/HAART− subjects. Furthermore, when assessing HIV+/HAART− participants both before and after starting on medications no significant changes were observed in subcortical and cortical volumes despite good virological control. Although no deleterious structural alterations could be specifically attributed to HAART, this cross-sectional study was not designed to determine with certainty if HAART is toxic to brain structures. Larger longitudinal studies with structured assessment endpoints are required for HIV+ participants receiving HAART.

In this study we also observed no significant correlations between laboratory values such plasma HIV values (CD4 current, CD4 nadir, or log10 plasma HIV VL) and structural neuroimaging measures. A number of studies have observed no correlation between current CD4 or nadir CD4 and brain volumes 12, 22, 25, 57. However, other investigators have observed a strong correlation between laboratory values, especially CD4 nadir, and brain volumes 17, 21, 46, 53–56, 58. A complex relationship may exist with a reduction in brain volumetric loss occurring not only at a lower CD4 nadir but also at a higher current CD4 cell count due to significant inflammation associated with reconstitution 55. Observed differences between various groups may reflect differences in the 1) sample size studied, 2) when a subject was scanned in relation to starting medications, 3) methods used for brain segmentation 46, and 4) regions investigated. Additional longitudinal studies of larger cohorts of HIV+ participants on stable HAART need to be performed.

Our exploratory analysis using a broken stick model demonstrated that brain atrophy may slowly develop over time. Based upon the self-reported duration of infection our model estimates a period of ~13 years is required for atrophy within the caudate to reach levels observed in this study. These changes can occur despite initiation of HAART as most HIV+ participants were prescribed medications when they met current guidelines (CD4 cell count < 350 cells/mm3 or an AIDS defining illness). A wide variability existed for this effect. Our exploratory results suggest that a chronic, subclinical process continues to occur within the caudate despite peripheral control of viral replication 24. Observed atrophy within the caudate could reflect low level inflammation and neuronal loss 10, 21. Initiation of adjunctive therapies soon after initial infection could be beneficial in an attempt to preserve brain integrity within the caudate 16. Additional longitudinal studies are required in acute and early HIV+ participants to confirm the effects of HIV on this brain structure.

Both HIV and aging independently affect brain volume regardless of HAART status. Previous studies using structural imaging 24, magnetic resonance spectroscopy 10, 33 and arterial spin labeling 8 have shown that age and HIV independently affect the brain. Our results are similar to these previous studies. In our cohort, HIV led to ~ 17 years of aging of the brain. No interaction was occurred between HIV and aging. However, in each of the previous studies that assessed HIV and aging HIV+ participants both on and off HAART were combined into a single group and compared to HIV− HIV−. In this study, HIV+ individuals were specifically divided into two groups (HIV+/HAART− and HIV+/HAART+) in order to identify the possible effects of HAART on structural brain changes as they relate to HIV. No significant differences were seen between HIV+/HAART− and HIV+/HAART− in regards to caudate volume as a function of age. Overall, our results suggest that a decrease in brain integrity within older HIV+ participants, even those taking HAART, may indicate that these individuals have increased vulnerability for subsequently developing neurodegenerative disorders.

In terms of neuropsychological function the HIV+/ HAART-group performed worse than HIV−. The HIV+/HAART+ also had mild cognitive disturbances but did not perform significantly worse than HIV− individuals. These changes in neuropsychological performance were not correlated with volumetric measures. The HIV+/HAART+ group had lower mean volumetric measures for most ROIs despite having better NPZ-4 test performances. The etiology of this discordance between neuroimaging and neuropsychological performance remains unknown. Previously, HAART has been shown to lead to mild improvements in neuropsychological performance 26. While a slight improvement in neuropsychological performance was seen after starting HAART, these changes were not significant in the subgroup of HIV+ participants assessed longitudinally. These changes may be influenced by practice effects or the test battery used. A rather limited number of neuropsychological tests were administered in this study and therefore may not be sensitive to possible subtle changes in cognition. Previous work has described the relationships between neuropsychological performance and neuroimaging in greater detail 18.

A limitation of this study was that the two HIV+ groups differed significantly in their self-reported duration of HIV infection. Participants may not have accurate recall of the time they seroconverted or may initially present to a healthcare provider at different stages of the disease. Larger longitudinal studies that follow HIV+ participants soon after documented seroconversion are needed to assess changes in brain volume due to HIV. In addition, this study was unable to assess if particular regimens could further modify brain atrophy. The effects of CPE on brain volumetric measures could not be assessed as most participants were prescribed only a limited number of regimens. On average, most HIV+ participants were taking regimens with relatively good brain penetration (average CPE=7). Further studies comparing brain volumetric between HIV+ participants on high and low CPE regimens are needed.

In summary, this study has demonstrated that HIV continues to be associated with brain atrophy within subcortical regions in the HAART era. It is possible that this volume change occurs slowly over time even with the initiation of HAART. It is therefore important that HIV is diagnosed early with additional neuroprotective agents considered for preventing volume loss with subcortical areas. In addition, both HIV and age could independently decrease brain volume but no significant interaction was observed. Additional studies of older HIV+ (>50 years old) are needed determine if they are at increased vulnerability for subsequently developing neurodegenerative diseases.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

B.A. proposed the project, performed statistical analyses, drafted the manuscript, and supervised the project, M.O. analyzed the data, and revised the manuscript, F.V. performed statistical analyses, J.H analyzed the data and revised the manuscript, and R.P. revised the manuscript.

Funding support came from National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) K23MH081786 (BMA) R01MH22005 (F.V.), R01MH085604(RP); National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) R01NR012907 (BMA), R01NR012657 (BMA); National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease R01AI47033 (F.V.); and Dana Foundation (DF10052) (BMA).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts: Dr. Ances serves on a scientific advisory panel for Lilly Pharmaceuticals. He is currently receiving studying anti-dementia drugs with Pfizer. Drs. Vaida and Paul have no conflicts. Mr. Ortega and Ms. Heaps have no conflicts.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lima VD, Hogg RS, Harrigan PR, et al. Continued improvement in survival among HIV-infected individuals with newer forms of highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2007 Mar 30;21(6):685–692. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32802ef30c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deeks SG. HIV infection, inflammation, immunosenescence, and aging. Annu Rev Med. 2011 Feb 18;62:141–155. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-042909-093756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Effros RB, Fletcher CV, Gebo K, et al. Aging and infectious diseases: workshop on HIV infection and aging: what is known and future research directions. Clin Infect Dis. 2008 Aug 15;47(4):542–553. doi: 10.1086/590150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desquilbet L, Jacobson LP, Fried LP, et al. HIV-1 infection is associated with an earlier occurrence of a phenotype related to frailty. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007 Nov;62(11):1279–1286. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.11.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desquilbet L, Margolick JB, Fried LP, et al. Relationship between a frailty-related phenotype and progressive deterioration of the immune system in HIV-infected men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009 Mar 1;50(3):299–306. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181945eb0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Onen NF, Overton ET. A review of premature frailty in HIV-infected persons; another manifestation of HIV-related accelerated aging. Curr Aging Sci. 2011 Feb;4(1):33–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Onen NF, Overton ET, Seyfried W, et al. Aging and HIV infection: a comparison between older HIV-infected persons and the general population. HIV Clin Trials. 2011 Mar–Apr;11(2):100–109. doi: 10.1310/hct1102-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ances BM, Vaida F, Yeh MJ, et al. HIV infection and aging independently affect brain function as measured by functional magnetic resonance imaging. J Infect Dis. 2010 Feb 1;201(3):336–340. doi: 10.1086/649899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang L, Andres M, Sadino J, et al. Impact of apolipoprotein E epsilon4 and HIV on cognition and brain atrophy: Antagonistic pleiotropy and premature brain aging. Neuroimage. 2011 Jul 21; doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harezlak J, Buchthal S, Taylor M, et al. Persistence of HIV-associated cognitive impairment, inflammation, and neuronal injury in era of highly active antiretroviral treatment. AIDS. 2011 Mar 13;25(5):625–633. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283427da7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark US, Cohen RA. Brain dysfunction in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: implications for the treatment of the aging population of HIV-infected individuals. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2011 Aug;11(8):884–900. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aylward EH, Henderer JD, McArthur JC, et al. Reduced basal ganglia volume in HIV-1-associated dementia: results from quantitative neuroimaging. Neurology. 1993 Oct;43(10):2099–2104. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.10.2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heindel WC, Jernigan TL, Archibald SL, Achim CL, Masliah E, Wiley CA. The relationship of quantitative brain magnetic resonance imaging measures to neuropathologic indexes of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arch Neurol. 1994 Nov;51(11):1129–1135. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1994.00540230067015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kieburtz KD, Ketonen L, Zettelmaier AE, Kido D, Caine ED, Simon JH. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in HIV cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 1990 Jun;47(6):643–645. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1990.00530060051016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Post MJ, Berger JR, Duncan R, Quencer RM, Pall L, Winfield D. Asymptomatic and neurologically symptomatic HIV-seropositive subjects: results of long-term MR imaging and clinical follow-up. Radiology. 1993 Sep;188(3):727–733. doi: 10.1148/radiology.188.3.8351340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen RA, Harezlak J, Gongvatana A, et al. Cerebral metabolite abnormalities in human immunodeficiency virus are associated with cortical and subcortical volumes. J Neurovirol. 2010 Nov;16(6):435–444. doi: 10.3109/13550284.2010.520817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen RA, Harezlak J, Schifitto G, et al. Effects of nadir CD4 count and duration of human immunodeficiency virus infection on brain volumes in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era. J Neurovirol. 2010 Feb;16(1):25–32. doi: 10.3109/13550280903552420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paul RH, Ernst T, Brickman AM, et al. Relative sensitivity of magnetic resonance spectroscopy and quantitative magnetic resonance imaging to cognitive function among nondemented individuals infected with HIV. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2008 Sep;14(5):725–733. doi: 10.1017/S1355617708080910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paul RH, Yiannoutsos CT, Miller EN, et al. Proton MRS and neuropsychological correlates in AIDS dementia complex: evidence of subcortical specificity. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007 Summer;19(3):283–292. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2007.19.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Archibald SL, Masliah E, Fennema-Notestine C, et al. Correlation of in vivo neuroimaging abnormalities with postmortem human immunodeficiency virus encephalitis and dendritic loss. Arch Neurol. 2004 Mar;61(3):369–376. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiang MC, Dutton RA, Hayashi KM, et al. 3D pattern of brain atrophy in HIV/AIDS visualized using tensor-based morphometry. Neuroimage. 2007 Jan 1;34(1):44–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klunder AD, Chiang MC, Dutton RA, et al. Mapping cerebellar degeneration in HIV/AIDS. Neuroreport. 2008 Nov 19;19(17):1655–1659. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e328311d374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lepore N, Brun C, Chou YY, et al. Generalized tensor-based morphometry of HIV/AIDS using multivariate statistics on deformation tensors. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2008 Jan;27(1):129–141. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2007.906091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Becker JT, Maruca V, Kingsley LA, et al. Factors affecting brain structure in men with HIV disease in the post-HAART era. Neuroradiology. 2011 Mar 22; doi: 10.1007/s00234-011-0854-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Becker JT, Sanders J, Madsen SK, et al. Subcortical brain atrophy persists even in HAART-regulated HIV disease. Brain Imaging Behav. 2011 Jun;5(2):77–85. doi: 10.1007/s11682-011-9113-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cysique LA, Brew BJ. Neuropsychological functioning and antiretroviral treatment in HIV/AIDS: a review. Neuropsychol Rev. 2009 Jun;19(2):169–185. doi: 10.1007/s11065-009-9092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.White MG, Wang Y, Akay C, Lindl KA, Kolson DL, Jordan-Sciutto KL. Parallel high throughput neuronal toxicity assays demonstrate uncoupling between loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and neuronal damage in a model of HIV-induced neurodegeneration. Neurosci Res. 2010 Jun;70(2):220–229. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giunta B, Ehrhart J, Obregon DF, et al. Antiretroviral medications disrupt microglial phagocytosis of beta-amyloid and increase its production by neurons: implications for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Mol Brain. 2011;4(1):23. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-4-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liner KJ, 2nd, Ro MJ, Robertson KR. HIV, antiretroviral therapies, and the brain. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2010 May;7(2):85–91. doi: 10.1007/s11904-010-0042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marra CM, Zhao Y, Clifford DB, et al. Impact of combination antiretroviral therapy on cerebrospinal fluid HIV RNA and neurocognitive performance. AIDS. 2009 Jul 17;23(11):1359–1366. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832c4152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robertson KR, Su Z, Margolis DM, et al. Neurocognitive effects of treatment interruption in stable HIV-positive participants in an observational cohort. Neurology. 2010 Apr 20;74(16):1260–1266. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d9ed09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ciccarelli N, Fabbiani M, Di Giambenedetto S, et al. Efavirenz associated with cognitive disorders in otherwise asymptomatic HIV-infected participants. Neurology. 2011 Apr 19;76(16):1403–1409. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821670fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ernst T, Jiang CS, Nakama H, Buchthal S, Chang L. Lower brain glutamate is associated with cognitive deficits in HIV participants: a new mechanism for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010 Nov;32(5):1045–1053. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Gorp WG, Miller EN, Satz P, Visscher B. Neuropsychological performance in HIV-1 immunocompromised participants: a preliminary report. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1989 Oct;11(5):763–773. doi: 10.1080/01688638908400930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heaton RK, Franklin DR, Ellis RJ, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders before and during the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: differences in rates, nature, and predictors. J Neurovirol. 2011 Feb;17(1):3–16. doi: 10.1007/s13365-010-0006-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Letendre SL, Ellis RJ, Ances BM, McCutchan JA. Neurologic complications of HIV disease and their treatment. Top HIV Med. 2010 Apr–May;18(2):45–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fischl B, Salat DH, Busa E, et al. Whole brain segmentation: automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron. 2002 Jan 31;33(3):341–355. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fischl B, Salat DH, van der Kouwe AJ, et al. Sequence-independent segmentation of magnetic resonance images. Neuroimage. 2004;23 Suppl 1:S69–S84. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Messina D, Cerasa A, Condino F, et al. Patterns of brain atrophy in Parkinson's disease, progressive supranuclear palsy and multiple system atrophy. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2011 Mar;17(3):172–176. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Labate A, Cerasa A, Aguglia U, Mumoli L, Quattrone A, Gambardella A. Voxel-based morphometry of sporadic epileptic participants with mesiotemporal sclerosis. Epilepsia. Apr;51(4):506–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raz N, Rodrigue KM, Kennedy KM, Head D, Gunning-Dixon F, Acker JD. Differential aging of the human striatum: longitudinal evidence. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003 Oct;24(9):1849–1856. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Westfall PH, Troendle JF. Multiple testing with minimal assumptions. Biom J. 2008 Oct;50(5):745–755. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200710456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cleveland W. Robust Locally Weighted Regression and Smoothing Scatterplots. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1979;74(368):829–883. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vieth E. Fitting piecewise linear regression functions to biological responses. J Appl Physiol. 1989 Jul;67(1):390–396. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.67.1.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lindsey JK, Jones B. Choosing among generalized linear models applied to medical data. Stat Med. 1998 Jan 15;17(1):59–68. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980115)17:1<59::aid-sim733>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dewey J, Hana G, Russell T, et al. Reliability and validity of MRI-based automated volumetry software relative to auto-assisted manual measurement of subcortical structures in HIV-infected participants from a multisite study. Neuroimage. 2010 Jul 15;51(4):1334–1344. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Masliah E, Heaton RK, Marcotte TD, et al. Dendritic injury is a pathological substrate for human immunodeficiency virus-related cognitive disorders. HNRC Group. The HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center. Ann Neurol. 1997 Dec;42(6):963–972. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brew BJ, Rosenblum M, Cronin K, Price RW. AIDS dementia complex and HIV-1 brain infection: clinical-virological correlations. Ann Neurol. 1995 Oct;38(4):563–570. doi: 10.1002/ana.410380404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fujimura RK, Goodkin K, Petito CK, et al. HIV-1 proviral DNA load across neuroanatomic regions of individuals with evidence for HIV-1-associated dementia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1997 Nov;16(1)(3):146–152. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199711010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Langford D, Marquie-Beck J, de Almeida S, et al. Relationship of antiretroviral treatment to postmortem brain tissue viral load in human immunodeficiency virus-infected participants. J Neurovirol. 2006 Apr;12(2):100–107. doi: 10.1080/13550280600713932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ances BM, Roc AC, Wang J, et al. Caudate blood flow and volume are reduced in HIV+ neurocognitively impaired participants. Neurology. 2006 Mar 28;66(6):862–866. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000203524.57993.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jernigan TL, Archibald S, Hesselink JR, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging morphometric analysis of cerebral volume loss in human immunodeficiency virus infection. The HNRC Group. Arch Neurol. 1993 Mar;50(3):250–255. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1993.00540030016007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cardenas VA, Meyerhoff DJ, Studholme C, et al. Evidence for ongoing brain injury in human immunodeficiency virus-positive participants treated with antiretroviral therapy. J Neurovirol. 2009 Jul;15(4):324–333. doi: 10.1080/13550280902973960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Di Sclafani V, Mackay RD, Meyerhoff DJ, Norman D, Weiner MW, Fein G. Brain atrophy in HIV infection is more strongly associated with CDC clinical stage than with cognitive impairment. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 1997 May;3(3):276–287. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jernigan TL, Archibald SL, Fennema-Notestine C, et al. Clinical factors related to brain structure in HIV: the CHARTER study. J Neurovirol. 2011 Jun;17(3):248–257. doi: 10.1007/s13365-011-0032-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stout JC, Ellis RJ, Jernigan TL, et al. Progressive cerebral volume loss in human immunodeficiency virus infection: a longitudinal volumetric magnetic resonance imaging study. HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center Group. Arch Neurol. 1998 Feb;55(2):161–168. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pfefferbaum A, Rosenbloom MJ, Rohlfing T, et al. Contribution of alcoholism to brain dysmorphology in HIV infection: effects on the ventricles and corpus callosum. Neuroimage. 2006 Oct 15;33(1):239–251. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thompson PM, Dutton RA, Hayashi KM, et al. 3D mapping of ventricular and corpus callosum abnormalities in HIV/AIDS. Neuroimage. 2006 May 15;31(1):12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.