Abstract

Regulation of mitochondrial outer membrane (MOM) permeability has dual importance: in normal metabolite and energy exchange between mitochondria and cytoplasm, and thus in control of respiration, and in apoptosis by release of apoptogenic factors into the cytosol. However, the mechanism of this regulation involving the voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC), the major channel of MOM, remains controversial. For example, one of the long-standing puzzles was that in permeabilized cells, adenine nucleotide translocase is less accessible to cytosolic ADP than in isolated mitochondria. Still another puzzle was that, according to channel-reconstitution experiments, voltage regulation of VDAC is limited to potentials exceeding 30 mV, which are believed to be much too high for MOM. We have solved these puzzles and uncovered multiple new functional links by identifying a missing player in the regulation of VDAC and, hence, MOM permeability – the cytoskeletal protein tubulin. We have shown that, depending on VDAC phosphorylation state and applied voltage, nanomolar to micromolar concentrations of dimeric tubulin induce functionally important reversible blockage of VDAC reconstituted into planar phospholipid membranes. The voltage sensitivity of the blockage equilibrium is truly remarkable. It is described by an effective “gating charge” of more than ten elementary charges, thus making the blockage reaction as responsive to the applied voltage as the most voltage-sensitive channels of electrophysiology are. Analysis of the tubulin-blocked state demonstrated that although this state is still able to conduct small ions, it is impermeable to ATP and other multi-charged anions because of the reduced aperture and inversed selectivity.

The findings, obtained in a channel reconstitution assay, were supported by experiments with isolated mitochondria and human hepatoma cells. Taken together, these results suggest a previously unknown mechanism of regulation of mitochondrial energetics, governed by VDAC interaction with tubulin at the mitochondria-cytosol interface. Immediate physiological implications include new insights into serine/threonine kinase signaling pathways, Ca2+ homeostasis, and cytoskeleton/microtubule activity in health and disease, especially in the case of the highly dynamic microtubule network which is characteristic of cancerogenesis and cell proliferation. In the present review, we speculate how these findings may help to identify new mechanisms of mitochondria-associated action of chemotherapeutic microtubule-targeting drugs, and also to understand why and how cancer cells preferentially use inefficient glycolysis rather than oxidative phosphorylation (Warburg effect).

Keywords: Voltage-dependent anion channel, mitochondria, microtubules, phosphorylation, signaling networks, selectivity

1. Introduction

The role of mitochondria in energy production, calcium signaling, and in promoting apoptotic signals is well-established. There is also emerging evidence of the involvement of mitochondria in multiple other cell signaling pathways and in control of metabolic and energy fluxes that to a great extent depend on the interaction of mitochondria with the cytoskeleton. The mitochondrial outer membrane (MOM) is the interface between the mitochondria and the cytosol, a “check point” for the fluxes of metabolites and energy exchange between the mitochondria and other cellular compartments and organelles. Permeabilization of MOM is also a “point of no return” to apoptotic cell death when, triggered by a variety of apoptotic stimuli and orchestrated by Bcl-2 family proteins, apoptogenic factors are released from mitochondria into the cytosol. MOM carries out a significant portion of its control functions through the voltage dependent anion channel (VDAC) that constitutes the main pathway for ATP/ADP and other mitochondrial metabolites across MOM [1–4]. Any imbalance in this exchange leads to an essential disturbance of cell metabolism, especially in the processes that require direct mitochondria participation [5].

Oxidative phosphorylation (OxPhos) requires efficient transport of metabolites, including cytosolic ADP, ATP, and inorganic phosphate, across both mitochondrial membranes for F1F0-ATPase to generate ATP in the matrix. It was recently asserted that VDAC is at the control point of mitochondria life and death and serves as a global regulator of mitochondrial function [2, 5–6]. This large channel plays the role of a “switch” that defines the direction in which mitochondria will go – to normal respiration or to suppression of mitochondrial metabolism that leads to apoptotic cell death. That’s why one of the central tasks is to find out which of the cellular compounds, such as kinases and other signaling molecules, regulate VDAC and consequently govern MOM permeability for ATP/ADP and other mitochondrial respiratory substrates.

The main focus of this review is the mechanism and physiological consequences of VDAC regulation by dimeric tubulin. Tubulin, the subunit of a microtubule (MT), is a heterodimer of α- and β-tubulin and one of the most abundant cytoskeleton proteins. It exists in this heterodimeric form under normal conditions. In the cytosol, the dimer is under dynamic equilibrium with MT, which is determined by temperature, concentrations of GTP, Ca2+, microtubule-associated proteins, and can be modified by a whole family of anticancer drugs, the so-called MT-targeting agents. These agents affect the equilibrium between polymerized and dimeric tubulin [7], leading to mitotic arrest and apoptosis [8–9].

We have discovered recently that dimeric tubulin induces reversible blockage of VDAC reconstituted into planar lipid membrane and dramatically reduces mitochondrial respiration [6, 10]. Regulation of VDAC by tubulin was first discovered in vitro and then related to the action of this protein in vivo. Thus, VDAC’s interaction with tubulin provides a novel functional link between mitochondrial respiration and the cytoskeleton. By this type of control, tubulin may selectively regulate metabolic fluxes between mitochondria and the cytosol, demonstrating a new role as a cytosolic regulator of VDAC and mitochondrial respiration.

2. VDAC blockage by tubulin

The intimate association of mitochondria with the microtubule network has long been known. Mitochondria are localized within and move along MT. More than 30 years ago, it was found that dimeric tubulin binds with high affinity to cellular membranes, including mitochondrial ones [11–13]. However, the exact domain of tubulin responsible for its binding to mitochondria, and hence MOM, has not yet been identified. Recently, Carre and coauthors [14] showed that tubulin is present in mitochondria isolated from different cell lines, normal and cancerous, representing ~ 2% of total cellular tubulin. In addition, a specific association of VDAC with tubulin was demonstrated by immunoprecipitation experiments [14].

2a. Kinetic analysis of tubulin binding to VDAC

We have found that tubulin at nanomolar concentrations induces highly voltage-sensitive blockage of VDAC reconstituted into planar lipid membranes [10]. A typical record of ion current through a single channel reconstituted into a planar bilayer in the presence of tubulin is shown in Fig. 1A. Tubulin induces fast, reversible, well time-resolved characteristic events of partial blockage of VDAC conductance in a 1–100 ms range. The blockage takes place at potentials of < 20 mV. By contrast, without tubulin addition at potentials of up to 30 mV, VDAC could stay in its high-conducting open state for quite a long time, sometimes for up to several hours. Under these experimental conditions, a relatively high voltage of 50 mV should be applied to induce VDAC closure (Fig. 1B). Upon this voltage-induced gating, channel conductance moves from a single high-conducting open state to the variety of low-conducting, so-called “closed” states. Once “closed”, VDAC can reside in the state of low conductance for extended periods of time until the voltage is relaxed to 0 mV. Reapplying the voltage restores the current corresponding to the high-conducting open state (Fig. 1B). By contrast, tubulin induces one well-resolved blocked state of VDAC with a narrow conductance distribution around 0.4 of the open-state conductance value. The conductance of the open state remains the same as without tubulin. Therefore, although the voltage-induced and tubulin-induced VDAC closures are both voltage-dependent and both lead to states of reduced conductance, the nature of these two processes appears to be quite different.

Figure 1.

Tubulin induces fast reversible events of partial blockage of VDAC, which differ from voltage-induced gating of the channel by kinetic parameters and conductance distribution. (A), A representative trace of ion current through a single channel before (left trace) and after (right trace) addition of 50 nM tubulin at −25 mV applied voltage. Tubulin induces a well-defined blocked state. Time-resolved blockage events are shown in Inset at a finer scale. (B), Typical voltage gating of VDAC in the absence of tubulin at −50 mV applied voltage. Voltage of this magnitude moves the channel from a single high-conducting open state to the variety of the low-conducting “closed” states. VDAC was isolated from N. crassa mitochondria. Bilayer membranes were formed from diphytanoyl phosphatidylcholine. Membrane bathing solution contained 1 M KCl with 5 mM HEPES at pH 7.4. The dashed lines indicate zero current. For the sake of presentation convenience, ion current was defined as positive when cations moved from the trans to cis side of the membrane. The records were filtered using an averaging time of 10 ms (except for 1 ms in Inset). (From [10]).

Tubulin induces VDAC closure in a concentration-dependent manner and only when a negative potential is applied from the side of tubulin addition. Application of negative potentials drives the net acidic tubulin towards the membrane. In the representative experiment shown in Fig 1A, tubulin was added to the cis side of the planar lipid chamber (the side of VDAC addition) and induced current closure at negative potentials. When a positive potential was applied, no blockage events were detected and the channel current was quiet and steady, as in the records without tubulin addition (data not shown). This observation, taken together with the fact that VDAC voltage gating is nearly symmetrical with respect to the applied voltage polarity [10], suggests that the channel is not altered by tubulin addition, and that fast-flickering current interruptions in Fig. 1A occur due to the reversible tubulin blockage of VDAC pore.

The distribution of times between blockage events, when the channel stays open (τon), is satisfactorily described by single exponential fitting (Fig. 2A, left). In the range of small tubulin concentrations [C], VDAC-tubulin binding could be adequately represented by a simple binding reaction with the on-rate constant, kon, calculated from the inverse average τon as kon = 1/(τon[C]). As expected for such a reaction, the on-rate of VDAC blockage by tubulin, kon[C], increased linearly with tubulin concentration [10]. However, it turns out that at high tubulin concentrations, the on-rate demonstrates a typical saturation (data not shown). Interestingly, similar saturating behavior was reported in 1983 by Bernier-Valentin et al., [12] in their experiments with 125I-labeled tubulin binding to the chromaffin granule and rat liver plasma membrane fractions, where the saturation was reached at ~100 nM tubulin.

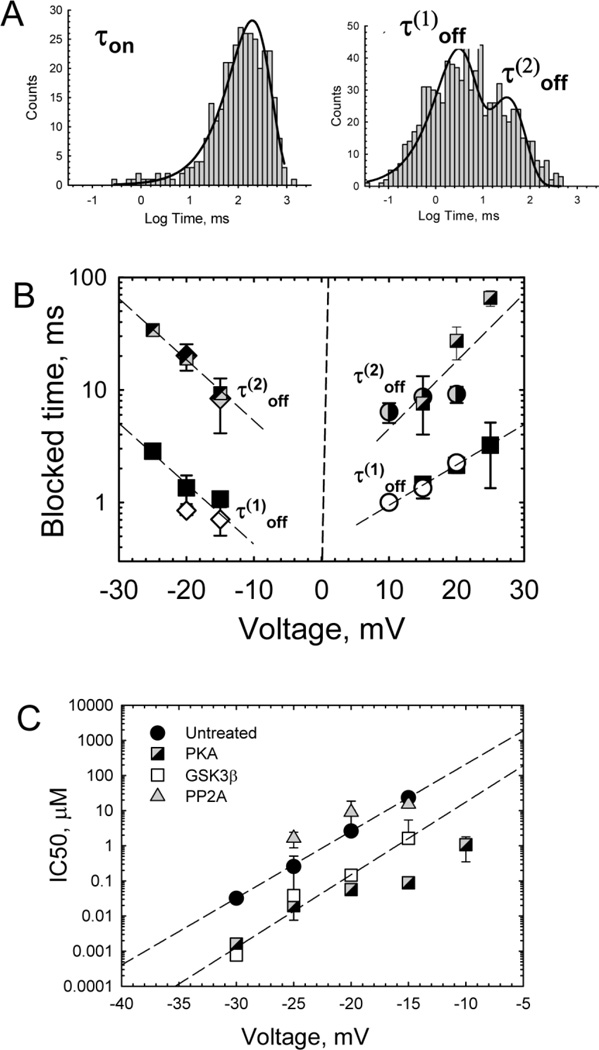

Figure 2.

Kinetic analysis of blockage events. (A), The distribution of times between blockage events, when the channel stays open (τon), is satisfactorily described by single exponential fitting. Distributions of the times spent by the channel in the blocked state require at least two exponents for fitting with characteristic times τ(1)off and τ(2)off . (B), Both characteristic times in the blocked state depend symmetrically on the applied voltage when tubulin is added to both sides (squares) or to either side of the membrane when the applied potential is more negative from the side of tubulin addition (cis side addition, diamonds; trans side addition, circles). (C), Voltage dependence of tubulin inhibitory concentration, IC50 (from [54]). IC50 strongly depends on the applied voltage and VDAC phosphorylation state. VDAC was isolated from mouse liver mitochondria with Triton x-100 and then phosphorylated by PKA or GSK3β, or dephosphorylated by PP2A. The IC50 values are averages over datasets obtained in 5–8 experiments with different VDAC samples. The dashed lines are fits to IC50 (V) = IC50(0) exp(nVF/RT), where V is the applied voltage, with the “effective gating charge” n = 11.2 and 12.2 for untreated and GSK3β phosphorylated VDAC, respectively. Other experimental conditions were as in Fig. 1.

Distributions of the times spent by the channel in the blocked state (Fig. 2A, right) cannot be described by a single exponent, and require at least two exponents for fitting with two distinctly different characteristic times, τ(1)off and τ(2)off. As expected for a simple dissociation reaction, the life-time of the tubulin-VDAC complex is independent of tubulin concentration [10]. The reason for two (as opposed to one) characteristic times is not understood at the moment and remains to be elucidated. Importantly, with symmetrical tubulin addition, both characteristic blocked times do not depend on the polarity of the applied voltage. They also do not depend on the side of tubulin addition if the polarity of the applied voltage is reversed accordingly (Fig. 2B). This finding, and also the strong dependence of τoff on the applied voltage, suggests that the mechanism of tubulin-VDAC binding is a restricted permeation block.

2b. Role of tubulin C-terminal tails in tubulin-VDAC interaction

The tubulin dimer of 100 kDa molecular weight and approximate dimensions of 8 nm × 4.5 nm × 6.5 nm [15–17] is far too large to permeate through the VDAC pore of 2.5–3.0 nm diameter [18]. Therefore, the plausible candidates for the proposed permeation block are anionic C-terminal tails (CTTs) of tubulin that both sterically and electrostatically can fit comfortably in the net positively charged VDAC pore. Furthermore, the length of both CTTs [17] is about the length of the VDAC pore of ~ 3 nm [18], so they could easily reach the tubulin binding site(s) inside the pore from either side of the membrane.

Experimental evidence supporting the requirement of intact CTT on the tubulin body for blocking VDAC is two-fold. First, tubulin with truncated CTT, tubulin-S, does not block VDAC [10]. Second, as much as 10 µM of the synthetic peptides of mammalian brain α- and β-tubulin CTT do not induce VDAC blockage either [10]. These results unambiguously demonstrate that CTTs should be attached to the main tubulin body to induce the characteristic VDAC blockage. Based on these results, a model of tubulin-VDAC interaction was suggested, wherein a negatively charged tubulin CTT partially blocks the positively charged channel lumen (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

A tentative model of the restricted permeation block of VDAC by tubulin. One of tubulin’s negatively charged C-terminal tails partially blocks the channel conductance by entering the VDAC pore in its open state and binding to the positively charged channel walls. The tubulin-blocked state is impermeable to ATP. The VDAC β-barrel protein (the three-dimensional model of mouse VDAC1 is adopted from [18]) is shown embedded in the lipid bilayer with the colored purple loops facing the “ cis “, or the cytosolic side of the channel. These loops are enriched with eight threonine and five serine residues, which are easily accessible for cytosolic kinases for phosphorylation, and are the plausible regions of tubulin main body binding. The model of tubulin dimer is adopted from [17].

Depending on the applied voltage and VDAC phosphorylation state (see section 4a below), the equilibrium constant of VDAC-tubulin binding, Keq, spans many orders of magnitude, with IC50 changing from nM to hundreds µM (Fig. 2C). Due to the complex distribution of the residence times (Fig. 2A, right panel), which could not be satisfactorily fitted by a single exponential, the concentration of half-inhibition, IC50, was calculated from the probability to find the channel in the tubulin-blocked state, PB [19]. At a given tubulin concentration [C] the probability is PB = [C].IC50/(1+ [C]/IC50), so that IC50 = (1 – PB)[C]/PB. The corresponding effective “gating charge” of the blockage is impressively high – it is about 11–12 elementary charges (Fig. 2C), which compares well with the gating charge of the most voltage-sensitive channels of electrophysiology [20]. The actual voltage across MOM and its possible variation with mitochondrial state are still debated (e.g. see discussion in [2]). The main source of the potential across MOM is believed to be the so called Donnan potential which arises due to the high concentration of non-permeable through VDAC charged macromolecules in the mitochondrial intermembrane space and cytosol [2]. The estimates for the voltage span the range from 10 mV [21], to 15–20 mV [22], to as high as 46 mV [23]. In the presence of tubulin, a pronounced VDAC blockage may occur at potentials as low as 5 mV (Fig. 2C), depending on tubulin concentration, type of VDAC, VDAC phosphorylation level, and membrane lipid composition. This immediately explains a long-standing dilemma of how VDAC gating observed at relatively high potentials on reconstituted channels, even if facilitated by the osmotic stress of the cell crowded cytosol [24], relates to the situation in MOM, where the estimated transmembrane potential is significantly lower.

The specificity of the VDAC-tubulin binding was supported by experiments with actin. It was found that actin, also an acidic cytoskeleton protein structurally different from tubulin and lacking CTTs, does not induce blockage events characteristic for tubulin [10]. Similarly to tubulin-S, actin induces current noise with fast events of τoff < 1 ms and a broad distribution of conductances of the closed states. The increased current noise obtained in the presence of tubulin-S indicates that the tubulin globular body interacts with VDAC even without CTT. However, these interactions are of a different nature than those with intact tubulin. The ability of the “tailless” tubulin to generate fast current noise of the channel open state could be a manifestation of interaction between the globule of tubulin and the channel entrance, in which some of the VDAC loops exposed on the membrane surface are likely to be involved.

Actin favors closed states of smaller conductance when added to the multichannel membrane, but does not significantly affect VDAC voltage-gating parameters. This agrees well with an earlier report of actin interaction with VDAC from N. crassa [25]. Taken together, the above data suggest that the mechanism of VDAC-tubulin interaction is rather complex, and CTT permeation into the VDAC pore is one of the steps which is characteristic for tubulin only. However, the observed effects of actin and tubulin-S on VDAC voltage gating and current noise of the open state suggest that VDAC could be responsible for binding of other cytoskeleton proteins [26–28]. There are a number of cytoskeleton proteins that are known to directly interact with MOM. One of them is desmin, a cytoskeleton protein that was shown to regulate mitochondria affinity to ADP and oxygen consumption supposedly through direct binding to VDAC [28].

3. VDAC in tubulin-blocked state is impermeable to ATP

It is believed that the major role of VDAC is in regulation of ATP/ADP exchange between mitochondria and the cytosol, not of small ion flux, so what is really important is the effect of tubulin blockage on adenine nucleotide transport. This question was addressed in a recent study from our laboratory [29].

3a. Effective size and selectivity of VDAC in tubulin-blocked state

The tubulin-blocked state is still highly ion-conductive and, at the specified experimental conditions, its conductance is 40% that of the open state. This implies that VDAC inhibition by tubulin is defined by the dimensions and selectivity of this residual conductive state. There is a long list of different compounds affecting VDAC voltage-gating (see [2–3, 30]) where large, non-permeating polyanions, such as König’s polyanion and dextran sulfate are the most potent inhibitors of VDAC [31–32]. In particular, König’s polyanion was shown to inhibit adenine nucleotide transport in isolated mitochondria [31] and cells [33]. However, the regulatory action of tubulin was recognized only very recently [6, 34].

The characteristic size of tubulin blocked state of VDAC was estimated using a method of neutral polymer partitioning into the channel [35–37]. The essence of this approach is to analyze penetration of differently sized poly(ethylene glycol)s, PEGs, into the channel water-filled pore by measuring its conductance in the presence of these polymers. The channel conductance responds differently to PEGs of different molecular weight, with polymers that are small enough to partition into the pore reducing its conductance in a weight-dependent manner. Based on the molecular weight of polymer that separates partitioning from exclusion into the tubulin-blocked state, w0 = 417 Da, (Fig. 4, red curve), we concluded that the effective cross-sectional area of VDAC is reduced by a factor of two as a result of the blockage by tubulin [29].

Figure 4.

The relative changes in conductance of the open and tubulin-blocked states of VDAC induced by addition of 15% (w/w) of PEG of different molecular weights to the membrane-bathing solutions. The ratio of channel conductance in the presence of PEG to its conductance in polymer-free solution is plotted against PEG molecular weight. The dashed line at 0.6 corresponds to the ratio of bulk solution conductivities with and without PEG [79]. Solid lines represent fitting to equation 1 in [29] with characteristic polymer molecular weights wo = 679 ± 47 for the open and 471 ± 31 for the tubulin-blocked states. (From [29]).

The size of the largest polymer that partitions into the open state, PEG 1000, appears to be smaller than that of PEG 3400 obtained by liposome swelling method [38]. This difference most likely is attributed to the inherent differences between PEG partitioning into the channel and liposome re-swelling methods. PEG molecules should enter the channel frequently and remain there for a sufficiently long time to affect conductance, while a lower rate of PEG entering the channel would only cause a decrease of the rate of liposome re-swelling. Thus, larger flexible polymers could show re-swelling in the liposome assay. A critical debate of which method is more accurate in estimating the channel’s restriction zone certainly is out of scope of this review. Regardless of the absolute values of the molecular weight of the excluded polymers, the important result is a well-defined shift of the polymer partitioning curve towards smaller PEGs upon transition of the channel to the blocked state (Fig. 4).

According to the proposed model of VDAC blockage by tubulin (Fig. 3), one could expect that the negatively charged tubulin CTTs penetrate into the channel lumen and make the net channel charge more negative, thus shifting channel ion selectivity towards more cationic. A similar effect on VDAC selectivity was previously described in the case of negatively charged synthetic phosphorothioate oligonucleotides permeating into the pore and blocking the channel [39]. Because at physiological salt concentrations ATP is a multi-charged anion, it is important to characterize the ionic selectivity of VDAC blocked by tubulin state at the salt concentrations close to those of physiologically relevant solutions. Indeed, in 150 mM vs. 50 mM gradient of KCl, the tubulin-blocked state of VDAC is favoring cations with the anion-to-cation permeability ratio of 1 : 3. This should be compared with the anion selectivity of the VDAC open state characterized by the anion-to-cation ratio of 4 : 1 [29].

A possible confusion might arise from the apparent similarity between the cation selectivity of the tubulin-blocked VDAC state and that observed at channel transition to the voltage-induced closed states [32, 40]. However, similarly to conductance, the selectivity of the tubulin-blocked state is well-defined and does not show the variability inherent in voltage-induced closed states. Importantly, conductance distribution of the voltage-induced closed states of VDAC is not only very broad [32, 38, 40], but it also depends on the magnitude and duration of applied voltage stimuli (e.g., slow triangular voltage wave versus steady state voltage). This is drastically different from the characteristics of the tubulin-induced blocked state described here. A possibility that one of the tubulin tails interacts with the VDAC voltage sensor and consequently enhances voltage-induced gating by “locking” the channel in one of the closed conformations cannot be entirely ruled out. However, a comparison of the properties of the tubulin-blocked state and voltage-induced closed states favors the CTT permeation block model over the tubulin enhanced voltage gating.

3b. ATP is excluded from the channel in its tubulin-blocked state

The bulk of recent research on “wide” channels (e.g., see [41–43]) demonstrates that their ionic selectivity is mostly of electrostatic origin. Therefore, the change in channel selectivity should be much more pronounced for the multi-charged ATP than for singly-charged chloride anion. Taken together with the additional steric hindrance in the blocked state, the tubulin-blocked state should be virtually impermeable to ATP. Indeed, our direct measurements of ATP partitioning into the tubulin-blocked state of VDAC, performed using an approach [44–45], similar to the one described above for PEGs, confirmed that ATP is excluded from the tubulin-blocked state [29].

4. Serine/threonine kinases regulate VDAC blockage by tubulin

Phosphorylation is commonly known as a general on/off regulation mechanism for numerous cellular processes. Therefore, it was reasonable to expect that phosphorylation of VDAC by cytosolic kinases might be important in cell signaling. Indeed, it was recently shown that VDAC could be phosphorylated by glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK3β), and that this phosphorylation is modulated by Akt-dependent inactivation of GSK3β [46–47]. Akt (also called protein kinase B, or an oncogene protein kinase) is known to localize to mitochondria along with GSK3β, one of its targets [48]. The majority of GSK3β is found in the cytosol, but some of it is accumulated on mitochondria. When hearts were treated with a GSK3β inhibitor in in vivo experiments [47], phosphorylation of VDAC was reduced. It was shown in vitro studies that protein kinase Cε (PKCε) can directly bind and phosphorylate VDAC1 [49]. Cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) is another serine-threonine kinase with established key roles in cell growth and differentiation. It is also one of the known targets in cancer therapy. Phosphorylation of cytoplasmic substrates mediated by PKA is crucial for multiple cell functions, including metabolism, differentiation, synaptic transmission, ion channel activity, growth and development [50]. PKA was shown lately to co-localize at mitochondria through interaction with the so-called A-kinase anchor proteins and to regulate mitochondrial respiration and dynamics [51]. The local activation of PKA leads to efficient phosphorylation of several mitochondrial substrates [52], suggesting VDAC as a potential PKA target [53].

4a. VDAC phosphorylation in vitro enhances tubulin blockage

We found that VDAC blockage by tubulin is extremely sensitive to the state of VDAC phosphorylation [54]. Phosphorylation of VDAC in vitro by common serine/threonine kinases PKA or GSK3β had resulted in a dramatic increase of the on-rate of VDAC-tubulin binding. Another remarkable effect of VDAC phosphorylation is the induction of a distinct asymmetry of tubulin blockage of VDAC. Untreated VDAC is blocked almost symmetrically at both voltage polarities when tubulin is added symmetrically to both sides of the membrane. VDAC phosphorylation with PKA or GSK3β changes this behavior drastically – the sensitivity of VDAC to tubulin increases by more than two orders of magnitude, but only for tubulin at the cis side of the channel, that is, the side of VDAC addition in reconstitution experiments [54]. The interaction from the trans side was virtually unchanged by VDAC phosphorylation. Not only the times of tubulin residence in the channel, but also two other basic properties of VDAC, single-channel conductance and selectivity, remained practically unaltered by VDAC phosphorylation, suggesting that the phosphorylation-induced modifications of VDAC take place outside its water-filled pore, on the cytosolic loops. The pronounced asymmetry of tubulin binding to phosphorylated VDAC suggests that the phosphorylation sites are positioned asymmetrically, on one side of the channel only.

4b. The tentative regions of VDAC phosphorylation

In recent years VDAC was identified as a target of different kinases, such as GSK3β [46], PKA [53], PKCε [49], Nek1 [55], and p38 Map kinase [56]. A few VDAC phosphorylation sites have been identified using a proteomic approach [57–58]. Here we are making an attempt to relate the suggested phosphorylation sites to our functional data on phosphorylated VDAC by mapping them on the available VDAC folding pattern of mouse VDAC1 determined by x-ray crystallography [18] and presented in Fig. 5.

Figure 5.

Folding pattern of the recombinant mouse VDAC-1 determined by x-ray crystallography (adapted from [18]). The boxed residues are identified VDAC phosphorylation sites: Thr-51, a GSK3β phosphorylation site [46]; Ser-12 and Ser-136, corresponding to the CaM-II/GSK3β andPKC consensus sites, respectively [57]; Ser-193, a Nek1 phosphorylation site [55]; and Ser-103, a target of endostatin-induced hexokinase 2 [61]. Three PKA and GSK3β common phosphorylation motifs are located on loops L5 and L7, facing the cytosolic side, and are circled.

Pastorino and coauthors [46] suggested that GSK3β phosphorylates VDAC at amino acids 51 to 55 because the mutation of Thr-51 to alanine abolished the ability of GSK3β to phosphorylate VDAC. According to the folding pattern, Thr-51 is located on the cytosolic Loop 1 (L1) (blue square in Fig. 5), and could be a plausible candidate for GSK3β phosphorylation site if a requirement of accessibility of phosphorylation sites for the cytosolic kinases is taken into account. However, according to the functional VDAC1 structure suggested by Colombini and coauthors [2, 59–60], this phosphorylation region is located on the mitochondrial interface of VDAC. Quite the opposite appears to be the case for another proposed VDAC1 phosphorylation site, Ser-193 [55]. It was shown that NIMA-related protein kinase (Nek1) could phosphorylate VDAC1 and that resulted in diminished cell death. This site is located on the 13th β-strand inside the channel lumen according to VDAC1 3D structure (Fig. 5), and on the cytosolic loop L4 according to the functional structure. It seems more likely that a cytosolic kinase would target a site located on an easily accessible cytosolic loop than a site buried inside the channel lumen. Ser-12 and Ser-136 were identified by phosphoproteomic analysis of VDAC1 post-translational modifications [57] and correspond to CaMII/GSK3β and PKC consensus sites, respectively. In both VDAC1 structures, these sites are located inside the pore on the α-helical N-terminus (Ser-12) and on the β-strand (Ser-136). Another identified VDAC serine phosphorylation residue, Ser-103, [61] is located on VDAC cytosolic side interface in both VDAC1 folding patterns and could be a target for hexokinase 2 [61]. Solving of the true structure of the functional VDAC is still under extensive ongoing debates (see [60, 62] and Colombini’s article in this issue) and is not a subject of the present review. Therefore, identification of VDAC phosphorylation sites is important not only for understanding VDAC’s role in mitochondrial metabolism and in promoting apoptotic signals, but also for deciphering the functional conformation of VDAC in vivo.

A further extensive mass spectrometry analysis is required for unambiguous identification of GSK3β and PKA phosphorylation sites of VDAC1. A simplistic approach is to map common serine/threonine phosphorylation motifs of PKA and GSK3β, which are RXX(S/T) and (S/T)XXX(S/T), respectively, on the VDAC1 structure. Figure 5 shows three tentative phosphorylation sites, one GSK3β, one PKA, and one shared, on loops L5 and L7 at one side of the channel (circles in Fig. 5) on the folding pattern of mouse VDAC1 determined by x-ray crystallography [18]. Four GSK3β and one PKA common phosphorylation motifs are located on the beta-strands hidden inside the channel lumen. If some of these sites became phosphorylated, it would introduce extra negative charges inside the channel lumen and affect channel selectivity, making it less anionic. Because the selectivity was found to be unaltered after VDAC phosphorylation with PKA of GSK3β, we conclude that these five sites most likely were not phosphorylated in vitro. The loops that connect β-strands of the β-barrel are exposed on the membrane interface and form channel entrances [18]. Loops L1, L5, and L7 with proposed Thr/Ser tentative phosphorylation cites (Fig. 5) seem to be very attractive candidates for phosphorylation regions because they are positioned asymmetrically at only one entrance of the channel. Such a positioning naturally explains the strictly asymmetrical effect of VDAC phosphorylation on tubulin binding, wherein phosphorylation controls the cis side on-rate [54]. Therefore, we conclude that in our reconstitution experiments these loops face the cis side of the bilayer, the side of VDAC addition, because this side of the channel is sensitized to tubulin interaction by phosphorylation (Fig. 3). This also allows us to suggest that this side corresponds to the cytosolic side of the channel, taking into account that phosphorylatable sites should be accessible for cytosolic kinases. Furthermore, eight (L1-L8) out of the total of nine loops in 3D VDAC structure that face the cis side are enriched with eight threonine and five serine residues that all could be potential serine/threonine kinase targets. Interestingly, the loops at the opposite, “trans”, or intermembrane side of the channel, have much fewer Ser/Thr residues (one serine and four threonines) (Fig. 5).

It is important to note here that the possibility to study phosphorylation-induced asymmetry in reconstitution experiments stems from the fact that VDAC insertion is unidirectional. According to our observations, in ~ 90% of experiments, VDAC inserts into the planar membranes formed from synthetic lipids unidirectionally [63]. In pure dioleoyl phosphatidylethanolamine (DOPE) [63] or diphytanoyl phosphatidylcholine (DPhPC) (T.K.R., personal communication), for instance, VDAC voltage-gating is measurably asymmetrical with respect to the sign of applied voltage. This asymmetry persists from experiment to experiment and indicates that most of the channels insert into the bilayer in the same direction. The asymmetry of VDAC gating depends on the membrane lipid composition, and is particularly pronounced in the presence of nonlamellar lipids, such as DOPE and cardiolipin [6, 63], both of which are characteristic lipids of MOM. In lamellar lipids, such as dioleoyl phosphatidylcholine (DOPC), VDAC voltage gating is almost symmetrical, but unidirectional VDAC insertion can be confirmed in specially designed experiments [63].

Interestingly, in spite of the differences in the suggested folding patterns of VDAC1 (for critical discussion, see [60]), the candidate Ser/Thr phosphorylation sites are similarly positioned on the external, presumably cytosolic loops in both models, and are in good agreement with our explanation of the asymmetry of the phosphorylation effect on VDAC blockage by tubulin.

Distler and colleagues [57] found different phosphorylation sites for each of the three VDAC isoforms. These authors proposed that the multiple phosphorylation sites could be related to the different physiological functions of the isoforms in vivo. It is tempting to suggest that VDAC interaction with tubulin could be a useful tool to approach an existing conundrum about the physiological roles and specificity of VDAC isoforms. Future work will elucidate connections between the differences in phosphorylation of VDAC isoforms and in their interaction with tubulin.

4c. A two-step model of VDAC-tubulin interaction

Based on our finding that phosphorylation does not alter VDAC selectivity and the off-rate of tubulin binding, and only affects tubulin binding on one side of the channel, we can suggest a two-step binding model where tubulin initially binds to the outside loop(s) with phosphorylation sites. The second step of the blockage reaction is permeation of the negatively charged tubulin CTT into the net positively charged VDAC pore. Once CTT is inside the pore, it dissociates with an off-rate that is highly voltage dependent but is not sensitive to the state of phosphorylation. This means that the phosphorylation sites outside the channel lumen do not interfere with the CTT binding site(s) inside the pore. Effectively, the consequence of tubulin interaction with the external loops is to increase its concentration at the VDAC pore entrance. There is a close analogy with the effect of adding charge(s) at the entrance of the gramicidin pore [64–65], which results in the change of local counter-ion concentration.

5. Physiological implications of VDAC blockage by tubulin

The findings described above establish a functional relationship between VDAC of the outer membrane of mitochondria and dimeric tubulin. What are the immediate physiological consequences of the newly uncovered roles for these “old” cytoskeletal and mitochondrial proteins?

5a. Tubulin decreases respiration rate of isolated mitochondria

It is reasonable to expect that the ATP-impermeable state of VDAC should result in a decrease of MOM permeability to ATP and ADP and for a number of other mitochondrial respiratory substrates, most of which are negatively charged. For the uncharged molecules the cut-off molecular weight of partitioning through the tubulin-blocked state is ~ 400 Da (Fig. 4), while for the negatively charged substrates an additional important restriction is introduced by an electrostatic barrier. For instance, non-charged creatine of 131 Da should permeate through the blocked state, but the flux of the negatively charged phosphocreatine of 255 Da is anticipated to be limited. However, Valdur Saks’ group has shown on the permeabilized intact cardiomyocytes that the apparent binding constant for phosphocreatine to mitochondrial creatine kinase that is resided in the intermembrane space does not change by tubulin associated to mitochondria [66–67]. These data could be interpreted that tubulin restricts VDAC permeability for ATP and ADP but does not do so for phosphocreatine. This apparent discrepancy between in vitro and in vivo results could, for instance, be due to the different sensitivity to tubulin between three VDAC isoforms which distribution is known to be highly tissue-dependent (e.g., see reviews by Messina et al. and Raghava et al. in this issue). VDAC1 is believed to be the most abundant isoform and, therefore, data obtained with VDAC isolated from mitochondria are traditionally referred to VDAC1. Strictly speaking, the effect of tubulin on VDAC permeability for ATP, ADP, phosphocreatine, creatine, and other metabolites in vitro should be compared for all three VDAC isoforms.

It is important to keep in mind that in the presence of tubulin, channel conductance fluctuates between the open and closed to ATP/ADP states. Therefore, tubulin dynamically restricts adenine nucleotide flux through VDAC, but does not eliminate it totally. These results suggest a new general mechanism of regulation of MOM permeability under normal and pathological conditions, where tubulin via its interaction with VDAC may selectively regulate metabolic fluxes between mitochondria and the cytosol. A key question is how this proposed mechanism of MOM permeability regulation is relevant to the situations in vivo.

Experiments with isolated mitochondria showed that dimeric tubulin reduces mitochondrial respiration. The apparent Km for exogeneous ADP increased ten times after the addition of 1–10 µM tubulin to mitochondria isolated from mouse heart or brain [10, 68]. The value of apparent Km for exogenous ADP represents the availability of ADP to ANT to activate oxidative phosphorylation. The addition of 1 µM of tubulin resulted in the appearance of a second component of mitochondrial respiration kinetics with Km more than 20 times higher than that for the first component and for the control without tubulin. The high Km component accounted for about 30% of the total ADP flux in mitochondria. This suggests that there is tubulin binding to mitochondria and this binding prevents ADP entry into mitochondria. Furthermore, the absence of variation of the maximal rate of respiration, Vmax, between the control and the second component of the respiration kinetics in the presence of tubulin highlights the integrity of the respiratory chain. The precise nature of the two components in the respiration kinetics is not clear at this time and needs further careful studies.

5b. Predicted effects of microtubule-targeting drugs in cell

Under physiological conditions, tubulin concentration does not change dramatically, but that may not be the case under stress or apoptotic stimuli. It was shown recently that Bcl-2 proteins could interact with tubulin and affect tubulin polymerization [69]. What seems quite relevant to tubulin-VDAC binding is that the interaction of Bcl-2 and tubulin requires the presence of the anionic CTT of α- and β-tubulin, as Bcl-2 proteins do not interact with tubulin-S. Such a direct association could be one of the regulatory mechanisms for apoptosis, leading to a shift of balance between tubulin dimers and polymerized tubulin and thus affecting tubulin-VDAC interaction. A similar rationale could be behind the effect of MT-targeting drugs, such as colchicine and paclitaxel (see diagram in Fig. 6A). These anticancer drugs target MT by either stabilizing MT (e.g., paclitaxel) or, conversely, by preventing their polymerization (e.g., colchicine).

Figure 6.

(A), A schematic of the effect of microtubule stabilizing and destabilizing agents, paclitaxel and colchicine, on the pool of free dimeric tubulin in the cytosol and, consequently, on mitochondrial potential (∆Ψ). Tubulin regulates MOM permeability for ATP/ADP by blocking VDAC to a degree which depends on tubulin concentration. (B), A schematic of the effect of PKA stimulation and inhibition on the state of VDAC phosphorylation, and, therefore, on mitochondrial potential. At the constant tubulin concentration in the cytosol, VDAC inhibition by tubulin depends on VDAC phosphorylation level and, therefore, affects ∆Ψ.

Remarkably, Maldonado and co-authors have recently shown in experiments on HepG2 human hepatoma cells that MT polymerization/depolymerization by paclitaxel or colchicine is coupled to modulation of mitochondrial potential and hence to oxidative phosphorylation [34]. Treatment of HepG2 cells with colchicine resulted in an increase of free dimeric tubulin and was accompanied by a loss of inner membrane potential, whereas paclitaxel reduced cytosolic free tubulin and caused an increase in membrane potential. These effects of MT-targeting drugs on mitochondrial membrane potential could be satisfactorily explained by the modulation of VDAC permeability for ATP/ADP by dimeric tubulin (Fig. 6A).

Though there are multiple very well-known primary targets for the MT-stabilizing and destabilizing drugs, the effects of these drugs on mitochondria have been reported recently [9, 70–72]. In particular, MT-targeting drugs also could induce apoptosis by promoting cytochrome c release from mitochondria in intact human neuroblastoma cells and isolated mitochondria [70]. Karbowski and coauthors have shown that depolymerization of MT by nocodazole or colchicine inhibits mitochondrial biogenesis [71]. It was shown that microtubule-targeting drugs could directly transiently hyperpolarize mitochondria and induce the mitochondrial network fragmentation as an early process associated with their pro-apoptotic activities [72]. For instance, treatment with taxol leads to disruption of the mitochondrial fission/fusion balance [73]. Our newly discovered regulation of VDAC by tubulin obviously adds an unexpected but important tack to the whole story – namely, that colchicine, paclitaxel, and other microtubule-targeting antitumor drugs could deliver a signal for MOM permeability regulation and apoptosis induction through the interaction of VDAC with cytosolic tubulin. Certainly, extensive research is needed for verification of the proposed scheme in vivo.

5c. VDAC blockage by tubulin as interpretation of PKA-dependent mitochondrial potential modulation in intact cells

How could VDAC phosphorylation, with its enhanced sensitivity to tubulin blockage affect mitochondria? Stimulation or inhibition of kinase activity might modulate VDAC blockage by tubulin and consequently affect MOM permeability for ATP/ADP and other respiratory substrates, thus leading to the changes in mitochondrial potential (see schematic in Fig. 6B). In fact, Maldonado and coauthors [34] had shown recently that PKA activation by cAMP in HepG2 cells results in a decrease of mitochondrial potential. Correspondingly, treatment of cells with a specific PKA inhibitor, H89, leads to hyperpolarization of mitochondria. These experiments with intact cells can be interpreted according to the findings with reconstituted VDAC, suggesting that tubulin binding to VDAC depends on the state of VDAC phosphorylation and regulates MOM permeability to respiratory substrates.

One open question is whether the regulation of mitochondrial potential and respiration through VDAC-tubulin interaction represents a general mechanism or is a hallmark of cancer cells only. Our results allow us to hypothesize that while VDAC in cancer and normal cells is the same, the state of its phosphorylation could be different [34]. That would lead to a different strength of interaction with tubulin and cause the consequent modification of mitochondrial potential and mitochondrial respiration. Interestingly, in primary hepatocytes, in contrast to cancer cells, paclitaxel and H89 did not cause mitochondrial hyperpolarization [34], whereas MT depolymerization with nocadazole caused a drop of potential similar to cancer cells. Recent data show a drastically different organization of mitochondria in cardiomyocytes and HL-1 cells of cardiac phenotype. In normal adult cardiomyocytes, mitochondria are arranged in a distinctly regular pattern between the MT lattice, while in HL-1 cells they are disorganized into a filamentous mitochondrial network [74]. This difference in mitochondria-cytoskeleton intracellular organization is accompanied by the high rate of respiration measured in permeabilized HL-1 cells in comparison with permeabilized cardiomyocites [74]. In addition, the intracellular distribution of four β-tubulin isoforms is different in normal and cancer cells [75] with the total absence of the tubulin β-II isoform in some of the cancer cells [76]. Whether such significant differences between mitochondria-cytoskeleton organization, mitochondrial respiration, and response to MT-targeting drugs found in normal and cancer cells are related to VDAC permeability modulation by free tubulin and VDAC phosphorylation state will be answered by future studies.

5d. General conclusions

The immediate implications of VDAC blockage by tubulin and its potential involvement in multiple cell signaling pathways are presented in the diagram of Fig. 7. Our speculations are based on the notion that VDAC, in its open state, maintains efficient ATP/ADP exchange across MOM, thus promoting oxidative phosphorylation and normal mitochondrial functioning. On the contrary, when VDAC is blocked by tubulin, fluxes of ATP/ADP and other respiratory substrates across MOM are restricted, leading to the reduction of oxidative phosphorylation, promotion of apoptotic signals, and eventually to cell death. Therefore, signals that enhance VDAC-tubulin binding by phosphorylating VDAC or by increasing the concentration of available free tubulin in the cytosol would reduce mitochondrial respiration. Conversely, inhibition of kinase activity or polymerization of MT would decrease VDAC blockage by tubulin, promoting the VDAC open state and increased respiration.

Figure 7.

Proposed implications of the VDAC-tubulin interaction. VDAC blockage by tubulin leads to a decrease in MOM permeability, reduction of oxidative phosphorylation (OxPhos), promotion of apoptotic signals, and, eventually, to cell death. Conversely, open VDAC supports oxidative phosphorylation. These processes depend on the concentration of free tubulin in cytosol and on the state of VDAC phosphorylation, and thus are regulated by cytosolic kinases. The stimuli that change the equilibrium between polymerized and dimeric tubulin by targeting microtubule (MT) affect VDAC inhibition by tubulin, and regulate MOM permeability and oxidative phosphorylation. Hexokinase 2 (HXK II) participates in the Warburg effect and is also known to bind to VDAC. Therefore, HXK 2 could compete with tubulin for binding to VDAC and regulate mitochondrial respiration.

If the above conjecture is true, our findings provide a range of new insights on serine/threonine kinase signaling pathways, Ca2+ homeostasis, and the role of cytoskeleton/microtubule remodeling in health and disease, especially in the case of the highly dynamic microtubule network which is characteristic of cell proliferation and cancerogenesis.

Our data support the hypothesis that a “glycolytic switch” characteristic for the majority of malignancies and known as the Warburg effect is coupled to the enhanced cytoskeletal remodeling involved in cancer cell motility typical for metastasis [77–78]. Cancer cells exhibit a profound change in energy metabolism and reactive oxygen species production by mitochondria. The kinase-regulated VDAC control over mitochondrial respiration discussed in this review could be crucially important for understanding the mitochondrial homeostasis and balance of reactive oxygen species in tumor cells.

Finally, our findings also link the effects of anticancer antiproliferative drugs to mitochondrial bioenergetics. Understanding the role of VDAC blockage by tubulin in the complex networks of MT-targeting drug action is an exciting subject for future research.

Highlights.

-

▪

Main in vitro and in vivo findings on VDAC blockage by tubulin are presented

-

▪

VDAC phosphorylation state and applied voltage define blockage equilibrium

-

▪

IC50 of the blockage spans the range of nanomolar to micromolar tubulin concentration

-

▪

Immediate implications for cell signaling in health and disease are discussed

Acknowledgements

These studies were supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The authors thank Philip Gurnev and Kely Sheldon for fruitful discussions.

Abbreviations

- CTT

C-terminal tail

- GSK3β

glycogen synthase kinase-3β

- MOM

mitochondrial outer membrane

- MT

microtubule

- OxPhos

oxidative phosphorylation

- PKA

cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase A

- VDAC

voltage-dependent anion channel

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rostovtseva T, Colombini M. ATP flux is controlled by a voltage-gated channelfrom the mitochondrial outer membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:28006–28008. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.45.28006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colombini M. VDAC: The channel at the interface between mitochondria and thecytosol. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2004;256:107–115. doi: 10.1023/b:mcbi.0000009862.17396.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rostovtseva TK, Tan WZ, Colombini M. On the role of VDAC in apoptosis: Factand fiction. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2005;37:129–142. doi: 10.1007/s10863-005-6566-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shoshan-Barmatz V, Israelson A, Brdiczka D, Sheu SS. The voltage-dependent anion channel(VDAC): function in intracellular signaling, cell life and cell death. Curr. Pharm. Design. 2006;12:2249–2270. doi: 10.2174/138161206777585111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lemasters JJ, Holmuhamedov E. Voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) asmitochondrial governator - Thinking outside the box. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1762:181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rostovtseva TK, Bezrukov SM. VDAC regulation: role of cytosolic proteins and mitochondrial lipids. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2008;40:163–170. doi: 10.1007/s10863-008-9145-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goncalves A, Braguer D, Kamath K, Martello L, Briand C, Horwitz S, Wilson L, Jordan MA. Resistance to Taxol in lung cancer cells associated with increased microtubule dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2001;98 doi: 10.1073/pnas.191388598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goncalves A, Braguer D, Carles G, Andre N, Prevot C, Briand C. Caspase-8 activation independent of CD95/CD95-L interaction during paclitaxel-induced apoptosis in human colon cancer cells (HT29-D4) Biochem. Pharmacol. 2000;60:1579–1584. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00481-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esteve MA, Carre M, Braguer D. Microtubules in apoptosis induction: Are they necessary? Curr. Cancer Drug Tar. 2007;7:713–729. doi: 10.2174/156800907783220480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rostovtseva TK, Sheldon KL, Hassanzadeh E, Monge C, Saks V, Bezrukov SM, Sackett DL. Tubulin binding blocks mitochondrial voltage-dependent anion channel and regulates respiration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2008;105:18746–18751. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806303105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saetersdal T, Greve G, Dalen H. Associations between beta-tubulin and mitochondria in adult isolated heart myocytes as shown by immunofluorescence and immunoelectron microscopy. Histochemistry. 1990;95:1–10. doi: 10.1007/BF00737221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernier-Valentin F, Aunis D, Rousset B. Evidence for Tubulin-Binding Sites on Cellular Membranes - Plasma-Membranes Mitochondrial-Membranesand Secretory Granule Membranes. J. Cell Biol. 1983;97:209–216. doi: 10.1083/jcb.97.1.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heggeness MH, Simon M, Singer SJ. Associations of mitochondria with microtubules in cultured-cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1978;75:3863–3866. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.8.3863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carre M, Andre N, Carles G, Borghi H, Brichese L, Briand C, Braguer D. Tubulin is an inherent component of mitochondrial membranes that interacts with the voltage-dependent anion channel. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:33664–33669. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203834200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lowe J, Li H, Downing KH, Nogales E. Refined structure of alpha beta-tubulin at 3.5 A resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;313:1045–1057. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nogales E, Wolf SG, Downing KH. Structure of the alpha beta tubulin dimer by electron crystallography (vol 391pg 1991998) Nature. 1998;393:191–191. doi: 10.1038/34465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Priel A, Tuszynski JA, Woolf NJ. Transitions in microtubule C-termini conformations as a possible dendritic signaling phenomenon. Eur. Biophys. J. 2005;35 doi: 10.1007/s00249-005-0003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ujwal R, Cascio D, Colletier J-P, Faham S, Zhang J, Toro L, Ping P, Abramson J. The crystal structure of mouse VDAC1 at 2.3 A resolution reveals mechanistic insights into metabolite gating. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2008;105:17742–17747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809634105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nestorovich EM, Karginov VA, Berezhkovskii AM, Bezrukov SM. Blockage of Anthrax PA63 Pore by a Multicharged High-Affinity Toxin Inhibitor. Biophys J. 2010;99:134–143. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.03.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swartz KJ. Sensing voltage across lipid membranes. Nature. 2008;456:891–897. doi: 10.1038/nature07620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lemeshko VV. Theoretical evaluation of a possible nature of the outer membrane potential of mitochondria. Eur. Biophys. J. 2006;36:57–66. doi: 10.1007/s00249-006-0101-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cortese JD, Voglino AL, Hackenbrock CR. The ionic strength of the intermembrane space of intact mitochondria is not affected by the pH or volume of the intermembrane space. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1992;1100:189–197. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(92)90081-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Porcelli AM, Ghelli A, Zanna C, Pinton P, Rizzuto R, Rugolo M. pH difference across the outer mitochondrial membrane measured with a green fluorescent protein mutant. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;326:799–804. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.11.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zimmerberg J, Parsegian VA. Polymer inaccessible volume changes during opening and closing of a voltage-dependent ionic channel. Nature. 1986;323:36–39. doi: 10.1038/323036a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu X, Forbes JG, Colombini M. Actin modulates the gating of Neurospora crassa VDAC. J. Membr. Biol. 2001;180:73–81. doi: 10.1007/s002320010060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saks VA, Kuznetsov AV, Khuchua ZA, Vasilyeva EV, Belikova JO, Kesvatera T, Tiivel T. Control of Cellular Respiration in-Vivo by Mitochondrial Outer-Membrane and by Creatine-Kinase - a New Speculative Hypothesis - Possible Involvement of Mitochondrial-Cytoskeleton Interactions. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1995;27:625–645. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(08)80056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Appaix F, Kuznetsov AV, Usson Y, Kay L, Andrienko T, Olivares J, Kaambre T, Sikk P, Margreiter R, Saks V. Possible role of cytoskeleton in intracellular arrangement and regulation of mitochondria. Exp. Physiol. 2003;88:175–190. doi: 10.1113/eph8802511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Capetanaki Y. Desmin cytoskeleton: A potential regulator of muscle mitochondrial behavior and function. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2002;12:339–348. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(02)00184-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gurnev PA, Rostovtseva TK, Bezrukov SM. Tubulin-blocked state of VDAC studied by polymer and ATP partitioning. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:2363–2366. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shoshan-Barmatz V, Gincel D. The voltage-dependent anion channel - Characterization modulation and role in mitochondrial function in cell life and death. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2003;39:279–292. doi: 10.1385/CBB:39:3:279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benz R, Wojtczak L, Bosch W, Brdiczka D. Inhibition of adenine-nucleotide transport through the mitochondrial porin by a synthetic polyanion. FEBS Lett. 1988;231:75–80. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)80706-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colombini M. Voltage gating in the mitochondrial channel VDAC. J. Membr. Biol. 1989;111:103–111. doi: 10.1007/BF01871775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holmuhamedov E, Lemasters JJ. Ethanol exposure decreases mitochondrial outer membrane permeability in cultured rat hepatocytes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2009;481:226–233. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maldonado EN, Patnaik J, Mullins MR, Lemasters JJ. Free Tubulin Modulates Mitochondrial Membrane Potential in Cancer Cells. Cancer Res. 2011;70:10192–10201. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krasilnikov OV, Sabirov RZ, Ternovsky VI, Merzliak PG, Muratkhodjaev JN. A simple method for the determination of the pore radius of ion channels in planar lipid bilayer-membranes. FEMS Microbiol. Immunol. 1992;105:93–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb05891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bezrukov SM, Vodyanoy I, Brutyan RA, Kasianowicz JJ. Dynamics and free energy of polymers partitioning into a nanoscale pore. Macromolecules. 1996;29:8517–8522. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nestorovich EM, Karginov VA, Bezrukov SM. Polymer partitioning and ion selectivity suggest asymmetrical shape for the membrane pore formed by epsilon toxin. Biophys. J. 2010;99:782–789. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Colombini M. Pore-size and properties of channels from mitochondria isolated from Neurospora crassa. J. Membr. Biol. 1980;53:79–84. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tan WZ, Loke YH, Stein CA, Miller P, Colombini M. Phosphorothioate oligonucleotides block the VDAC channel. Biophys. J. 2007;93:1184–1191. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.105379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hodge T, Colombini M. Regulation of metabolite flux through voltage-gating of VDAC channels. J. Membr. Biol. 1997;157:271–279. doi: 10.1007/s002329900235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blachly-Dyson E, Peng SZ, Colombini M, Forte M. Selectivity changes in site- directed mutants of the VDAC ion channel - structural implications. Science. 1990;247:1233–1236. doi: 10.1126/science.1690454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alcaraz A, Nestorovich EM, Aguilella-Arzo M, Aguilella VM, Bezrukov SM. Salting out the ionic selectivity of a wide channel: The asymmetry of OmpF. Biophys. J. 2004;87:943–957. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104/043414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aguilella VM, Queralt-Martin M, Aguilella-Arzo M, Alcaraz A. Insights on the permeability of wide protein channels: measurement and interpretation of ion selectivity. Integr. Biol. - UK. 2011;3:159–172. doi: 10.1039/c0ib00048e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rostovtseva TK, Bezrukov SM. ATP transport through a single mitochondrial channel VDACstudied by current fluctuation analysis. Biophys. J. 1998;74:2365–2373. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77945-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rostovtseva TK, Komarov A, Bezrukov SM, Colombini M. Dynamics of nucleotides in VDAC channels: Structure-specific noise generation. Biophys. J. 2002;82:193–205. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75386-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pastorino JG, Hoek JB, Shulga N. Activation of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta disrupts the binding of hexokinase II to mitochondria by phosphorylating voltage- dependent anion channel and potentiates chemotherapy-induced cytotoxicity. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10545–10554. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Das S, Wong R, Rajapakse N, Murphy E, Steenbergen C. Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 inhibition slows mitochondrial sdenine nucleotide transport and regulates voltage-dependent anion channel phosphorylation. Circ. Res. 2008;103:983–U186. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.178970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bijur GN, Jope RS. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta is highly activated in nuclei and mitochondria. Neuroreport. 2003;14:2415–2419. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200312190-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baines CP, Song CX, Zheng YT, Wang GW, Zhang J, Wang OL, Guo Y, Bolli R, Cardwell EM, Ping PP. Protein kinase C epsilon interacts with and inhibits the permeability transition pore in cardiac mitochondria. Circ. Res. 2003;92:873–880. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000069215.36389.8D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Montminy M. Transcriptional regulation by cyclic AMP. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1997;66:807–822. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carlucci A, Lignitto L, Feliciello A. Control of mitochondria dynamics oxidative metabolism by cAMPAKAPs and the proteasome. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:604–613. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Feliciello A, Gottesman ME, Avvedimento EV. cAMP-PKA signaling to the mitochondria: protein scaffolds mRNA and phosphatases. Cell Signal. 2005;17:279–287. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bera AK, Ghosh S, Das S. Mitochondrial VDAC Can Be Phosphorylated by Cyclic-Amp-Dependent Kinase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Co. 1995;209:213–217. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sheldon KL, Maldonado EN, Lemasters JJ, Rostovtseva TK, Bezrukov SM. Phosphorylation of Voltage-Dependent Anion Channel by Serine/Threonine Kinases Governs its Interaction with Tubulin. PLOS ONE. 2011;6:e25539. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen Y, Craigen WJ, Riley DJ. Nek1 regulates cell death and mitochondrial membrane permeability through phosphorylation of VDAC1. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:257–267. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.2.7551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schwertz H, Carter JM, Abdudureheman M, Russ M, Buerke U, Schlitt A, Muller-Werdan U, Prondzinsky R, Werdan K, Buerke M. Myocardial ischemia/reperfusion causes VDAC phosphorylation which is reduced by cardioprotection with a p38 MAP kinase inhibitor. Proteomics. 2007;7:4579–4588. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Distler AM, Kerner J, Hoppel CL. Post-translational modifications of rat liver mitochondrial outer membrane proteins identified by mass spectrometry. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1774:628–636. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liberatori S, Canas B, Tani C, Bini L, Buonocore G, Godovac-Zimmermann J, Mishra OP, Delivoria-Papadopoulos M, Bracci R, Pallini V. Proteomic approach to the identification of voltage-dependent anion channel protein isoforms in guinea pig brain synaptosomes. Proteomics. 2004;4:1335–1340. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Song JM, Midson C, Blachly-Dyson E, Forte M, Colombini M. The topology of VDAC as probed by biotin modification. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:24406–24413. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.38.24406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Colombini M. The published 3D structure of the VDAC channel: native or not? Trends Biochem. Sci. 2009;34:382–389. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yuan SP, Fu Y, Wang XF, Shi HB, Huang YJ, Song XM, Li L, Song N, Luo YZ. Voltage-dependent anion channel 1 is involved in endostatin-induced endothelial cell apoptosis. FASEB J. 2008;22:2809–2820. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-107417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hiller S, Abramson J, Mannella C, Wagner G, Zeth K. The 3D structures of VDAC represent a native conformation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2010;35:514–521. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rostovtseva TK, Kazemi N, Weinrich M, Bezrukov SM. Voltage gating of VDAC is regulated by nonlamellar lipids of mitochondrial membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:37496–37506. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602548200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Apell HJ, Bamberg E, Alpes H, Lauger P. Formation of Ion Channels by a Negatively Charged Analog of Gramicidin-A. J. Membrane Biol. 1977;31:171–188. doi: 10.1007/BF01869403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Capone RF, Blake S, Mayer T, Restrepo MR, Yang J, Mayer M. Designing chemo-sensors based on charged derivatives of gramicidin a. Biophys. J. 2007:609A–610A. doi: 10.1021/ja0711819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guzun R, Timohhina N, Tepp K, Monge C, Kaambre T, Sikk P, Kuznetsov AV, Pison C, Saks V. Regulation of respiration controlled by mitochondrial creatine kinase in permeabilized cardiac cells in situ Importance of system level properties. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1787:1089–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Saks V, Guzun R, Timohhina N, Tepp K, Varikmaa M, Monge C, Beraud N, Kaambre T, Kuznetsov A, Kadaja L, Eimre M, Seppet E. Structure-function relationships in feedback regulation of energy fluxes in vivo in health and disease: Mitochondrial Interactosome. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1797:678–697. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Monge C, Beraud N, Kuznetsov AV, Rostovtseva T, Sackett D, Schlattner U, Vendelin M, Saks VA. Regulation of respiration in brain mitochondria, synaptosomes: restrictions of ADP diffusion in situ roles of tubulinand mitochondrial creatine kinase. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2008;318:94–1562. doi: 10.1007/s11010-008-9865-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Knipling L, Wolff J. Direct interaction of Bcl-2 proteins with tubulin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Co. 2006;341:433–439. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Andre N, Braguer D, Brasseur G, Goncalves A, Lemesle-Meunier D, Guise S, Jordan MA, Briand C. Paclitaxel induces release of cytochrome c from mitochondria isolated from human neuroblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5349–5353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Karbowski M, Spodnik JH, Teranishi M, Wozniak M, Nishizawa Y, Usukura J, Wakabayashi T. Opposite effects of microtubule-stabilizing and microtubule-destabilizing drugs on biogenesis of mitochondria in mammalian cells. J. Cell Sci. 2001;114:281–291. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.2.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rovini A, Savry A, Braguer D, Carre M. Microtubule-targeted agents: When mitochondria become essential to chemotherapy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1807:679–688. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Voccoli V, Colombaioni L. Mitochondrial remodeling in differentiating neuroblasts. Brain Res. 2009;1252:15–29. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Guzun R, Karu-Varikmaa M, Gonzalez-Granilo M, Kuznetsov A, Michel L, Cottet-Rousselle C, Saaremae M, Kaam T, Metsis M, Grimm M, Auffray C, Saks V. Mitochondria-cytoskeleton interaction: Distribution of β-tubulins in cardiomyocytes and HL-1 cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1807:458–469. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Burkhart CA, Kavallaris M, Horwitz SB. The role of beta-tubulin isotypes in resistance to antimitotic drugs. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2001;1471:O1–O9. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(00)00022-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hiser L, Aggarwal A, Young R, Frankfurter A, Spano A, Correia JJ, Lobert S. Comparison of beta-tubulin mRNA and protein levels in 12 human cancer cell lines. Cell Motil. Cytoskel. 2006;63:41–52. doi: 10.1002/cm.20109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mathupala SP, Ko YH, Pedersen PL. The pivotal roles of mitochondria in cancer: Warburg and beyond and encouraging prospects for effective therapies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1797:1225–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pani G, Galeotti T, Chiarugi P. Metastasis: cancer cell’s escape from oxidative stress. Cancer Metast. Rev. 2010;29:351–378. doi: 10.1007/s10555-010-9225-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stojilkovic KS, Berezhkovskii AM, Zitserman VY, Bezrukov SM. Conductivity and microviscosity of electrolyte solutions containing polyethylene glycols. J Chem Phys. 2003;119:6973–6978. [Google Scholar]