Abstract

Several bodies of research have found different results with regard to presentation timing, categorization, and generalization. Both presenting instances at the same time (simultaneous) and presenting instances apart in time (spacing) have been shown to facilitate generalization. In this study, we resolved these results by examining simultaneous, massed, and spaced presentations in 2-year-old children’s (N = 144) immediate and long-term performance on a novel noun generalization task. Results revealed that, when tested immediately, children in the simultaneous condition outperformed children in all other conditions. However, when tested after 15 minutes, children in the spaced condition outperformed children in all other conditions. Results are discussed in terms of how retrieval dynamics during learning affect abstraction, retention, and generalization across time.

Keywords: spacing effect, distributed learning, long-term memory, comparison, abstraction, categorization, generalization, word learning, cognitive development

Due to the central role of categorization and generalization in cognition, a considerable amount of research has examined the factors that promote generalization. One particular factor that has been shown to facilitate generalization is the timing with which instances of a category are presented. The findings of this research present a paradoxical set of results—both presenting instances at the same time, providing an opportunity to compare instances simultaneously, and presenting instances apart in time, by spacing the presentation of instances out in time, have been shown to facilitate generalization. In this study, we examine these findings by investigating how simultaneous, massed, and spaced learning schedules affect children’s in-the-moment and long-term generalization. Moreover, we identify a mechanism, ease of retrieval during learning, which may contribute to differences in performance across time.

Promoting Generalization: Comparison

Many studies have demonstrated that comparison, viewing multiple instances of a category simultaneously, facilitates category acquisition and generalization (e.g., Gentner, Loewenstein, Thompson, & Forbus, 2009; Oakes & Ribar, 2005). One major finding of these studies is that comparing multiple instances of the same category promotes generalization more so than viewing a single category instance. For example, in one study (Namy & Gentner, 2002), children viewed two category members simultaneously (e.g., a bicycle and a tricycle) and were then asked to select another member of the category (e.g., a skateboard). Results of the study indicated that viewing two of the same category members simultaneously, rather than viewing just one category member with a taxonomically unrelated object (e.g., a bicycle and a dumbbell), aided higher-level generalization of categories.

Furthermore, comparing multiple instances simultaneously appears to promote generalization more than viewing the same number of instances individually in immediate succession (e.g., Gentner et al., 2009; Kovack-Lesh & Oakes, 2007; Oakes & Ribar, 2005). For example, Oakes and Ribar (2005) presented children with two pictures of an animal (e.g., two cats), either simultaneously or in immediate succession. Children then participated in a generalization task in which they were required to discriminate between different categories (e.g., cats and vehicles). The results revealed that children who saw the pictures simultaneously were better at discriminating between closely related animals (e.g., cats and dogs) than children who saw the pictures in immediate succession. In sum, comparison appears to promote generalization more than viewing the same instances in immediate succession.

The focus of research on comparison has historically been on how simultaneous presentations facilitate abstraction and in-the-moment generalization. That is, learners are presented with a categorization task and are then given an immediate generalization task. However, more recent research on comparison has included a focus on examining how simultaneous presentations support retention and long-term generalization (e.g., Gentner et al., 2009; Star & Rittle-Johnson, 2009). These studies have argued that comparison supports the abstraction, retention, and generalization of conceptual information. As an example, in one study (Star & Rittle-Johnson, 2009) children viewed lessons about numerical estimation problems, presented either simultaneously (i.e., in pairs) or sequentially (i.e., one at a time). Children later completed tests of numerical estimation skills and numerical knowledge both immediately following the lessons and, importantly, after a two week delay. The results revealed that children in the simultaneous presentation condition had greater retention of the conceptual information after the two-week delay than did children in the sequential presentation condition. In sum, recent research on comparison suggests that simultaneous presentations promote more abstraction, retention, and generalization of information than sequential presentations.

Promoting Generalization: The Spacing Effect

A separate body of research has focused on examining learning and retention over longer time scales (e.g., Cepeda, Pashler, Vul, Wixted, & Rohrer, 2006; Ebbinghaus, 1885/1964). In striking contrast to comparison research, which suggests presenting learning events simultaneously, this line of research suggests that memory is enhanced when learning events are distributed in time, rather than massed in immediate succession. This robust finding is referred to as the spacing effect (e.g., Cepeda et al., 2006). For example, in one study (Cepeda, Vul, Rohrer, Wixted, & Pashler, 2008), learners were presented with trivia facts, either in immediate succession (massed) or with varying degrees of time between each presentation (spaced). After a delay, learners were asked to answer the trivia facts. Learners had higher performance for items that were presented on a spaced schedule and lower performance for items that were presented on a massed schedule. In sum, memory for previously viewed information is enhanced on a spaced learning schedule.

Moreover, recent research suggests that generalizing information to new instances is also enhanced on spaced learning schedules (e.g., Kornell & Bjork; 2008; Vlach, Sandhofer, & Kornell, 2008). For example, in one study (Kornell & Bjork, 2008) participants studied six different paintings by each of 12 relatively obscure artists on either a massed or spaced schedule. After a delay, participants were shown unfamiliar paintings by the same artists and asked to generalize an artist’s style to the unfamiliar paintings. Paintings presented on a spaced schedule were generalized more accurately that paintings presented on a massed schedule at test, suggesting that spaced presentations facilitated participants’ generalization to a greater degree than massed presentations.

Comparison and Spaced Learning

Historically, research on comparison has investigated questions of abstraction and generalization while research on spacing has focused on retention. However, more recent research on both comparison and the spacing effect has examined the same question: What are the learning conditions that support long-term generalization? In answering this question, both lines of research have sought to understand the conditions of the learning environment that promote abstraction, retention, and generalization as these processes occur in parallel. Surprisingly, this research has resulted in a paradoxical set of results.

How is it that comparison, the presentation of instances at the same time, and spaced learning, the presentation of instances presented apart in time, both facilitate long-term generalization? Reconciling these bodies of research is difficult because experiments have been designed so that massed (i.e., sequential) presentations are the control condition. Although both simultaneous and spaced presentations promote more long-term generalization than massed presentations, research has not directly compared simultaneous and spaced presentations. One possibility is that spaced presentations promote generalization more than massed presentations, but not more so than simultaneous presentations.

If this is the case, it would be important to understand the mechanisms underlying simultaneous presentations that contribute to higher long-term generalization performance. For example, simultaneous presentations may relieve learners of memory demands during learning, facilitating the ease of retrieval and generalization. Conversely, spaced presentations impose a memory demand upon learners, requiring them to think back in time to previous instances of the category, which may deter generalization. Thus, the ease of retrieval during learning could be contributing to differences in performance across learning conditions.

The current investigation addressed this issue by examining how presenting instances of a category on different learning schedules affects two-year-olds’ performance on a novel noun generalization task. In Experiment 1 and 2, two-year-old children were presented with novel object categories on one of three learning schedules: simultaneous, massed, and spaced. After learning, children were given a forced choice test in which they were required to generalize a label to a novel instance of the category, either immediately or after a 15 minute delay. In Experiment 2, children were asked to retrieve and generalize the label for objects during learning. We predicted that retrieval dynamics might be differing across the three learning conditions and that this could be contributing to differences in performance. In sum, these experiments allowed for a direct examination of different learning schedules in both in-the-moment and long-term generalization.

Experiment 1

Method

Participants

The participants were 72 2- to 2.5-year-old children (M = 26.4 months, range: 24–30 months). Half of the children were randomly assigned to immediate testing and the other half were assigned to 15 minute delayed testing. An equal number of children were randomly assigned to each presentation condition (simultaneous, massed, and spaced), resulting in 12 children in each condition of the study. Across conditions, there were no significant differences in age and there were an equal number of boys and girls in each condition.

All children were monolingual English speakers and recruited from a child participant database. Only children in which parents reported no family history of color blindness were recruited. In order to ensure that children’s productive vocabulary was equivalent across experimental conditions, parents completed the MacArthur Bates Communicative Development Inventory: Words & Sentences (MCDI) (Fenson, Dale, Reznick, Bates, Thal, & Pethick, 1994). Productive vocabulary did not differ significantly across the experimental conditions, F(1, 66) = .131, p > .05 (M = 456 words, range: 283 – 667, for all children).

Stimuli

Children were presented with eight target novel object categories. Each category contained four instances that varied in color, texture, and perceptual features, but all instances had the same shape (see Figure 1, Panel B, for examples). Each novel object was randomly assigned a novel label (e.g., “fep”). There were also eight distractor object categories presented. Each distractor object category contained one instance that differed in shape, color, texture, and perceptual features from the target object category (see Figure 1, Panel A). The object presentation order and object-label pairing was randomly assigned for each participant.

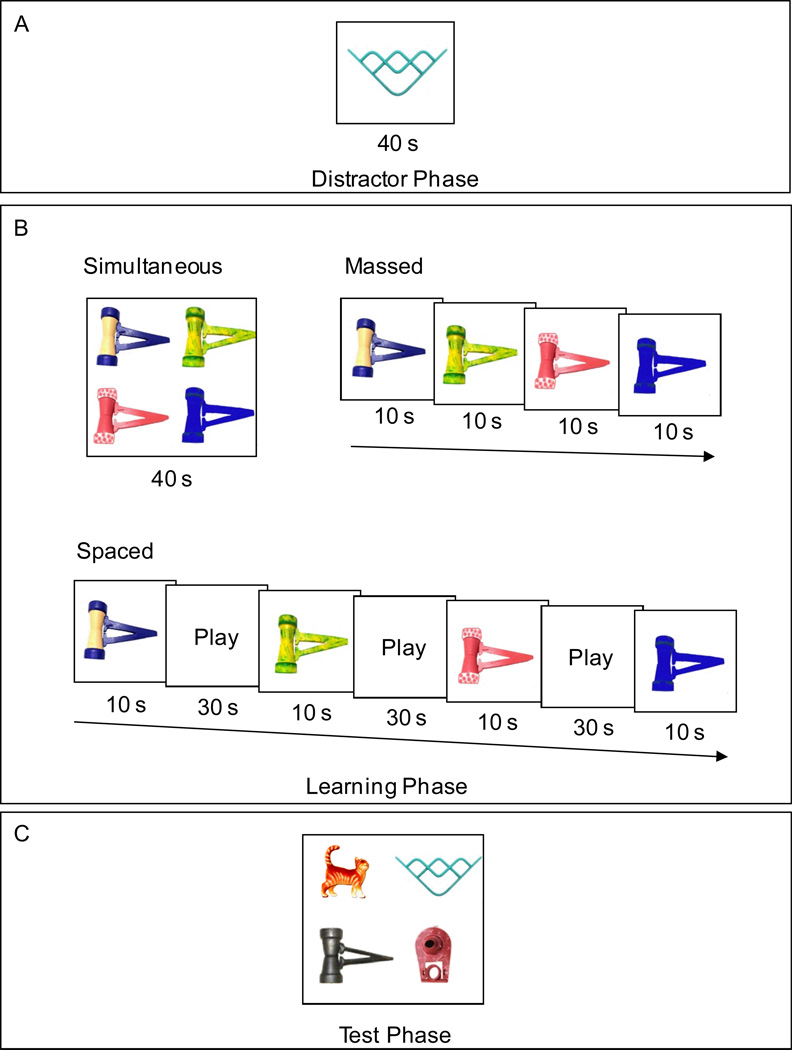

Figure 1.

Experimental procedure. (A) Distractor phase. A novel object was presented without a label (e.g., “it”). (B) Learning phase. Four novel objects were presented and given a label (e.g., “fep”) in simultaneous, massed, or spaced presentations. (C) Test phase. Four objects were presented and the child was asked to identify the target (e.g., “Can you hand me the fep?”). For children in the immediate condition, testing occurred directly after the learning phase. For children in the delayed testing condition, testing occurred 15 minutes after the learning phase.

At test, there were four objects presented (see Figure 1, Panel C). One object was a novel instance of the target category and one object was the distractor object. The third object was a novel object that differed in shape, color, texture, and perceptual features from all of the objects presented at test. The fourth object was a figurine of a familiar object (e.g., a toy dog) that was equivalent in size to all of the other objects.

Design

The study was a 3 (Presentation Timing) × 2 (Testing Delay) design. Presentation Timing (simultaneous, massed, and spaced) and Testing Delay (immediate or 15 minute delay) were both between-subjects factors.

Procedure

Two experimenters conducted the experimental session: one experimenter coordinated timing and organized the objects under a table so that they were not visible until presentation. During the presentations, the second experimenter kept the object in the child’s gaze at all times. If a child began to look away during an object presentation, the second experimenter moved the object into the child’s visual focus to maintain the child’s attention and ensure equivalent looking times across all trials.

During the experiment, children were introduced to eight sets of stimuli. Each set was presented in three phases: a distractor phase, a learning phase (simultaneous, massed, and spaced), and a test phase.

Distractor Phase

The distractor phase was the first phase of each trial. The purpose of introducing a distractor object was to have an object present during testing that was not the target object, but was presented during the experiment. This ensured that children were not simply responding based on the familiarity of the objects during the test. As depicted in Figure 1 (Panel A), a distractor object was presented for forty seconds and was not given a label (for example, the experimenter said, “Look at this!”). The distractor object was different in shape from the objects presented in the learning phase and was a novel object in every trial.

Learning Phase

The learning phase began immediately following the distractor phase. As depicted in Figure 1 (Panel B), in the simultaneous presentations, all of the instances were presented at the same time. In the massed presentations, objects were presented in immediate succession, with less than one second between presentations. In the spaced presentations, 30 seconds elapsed between each instance presentation. During this time, children participated in a distraction activity in which children played with play-doh and/or completed puzzles.

In all conditions, each object was allotted 10 seconds of viewing time. Thus, in the massed and spaced presentations, each of the four objects was presented for 10 seconds (for a total of 40 seconds). In the simultaneous condition, all of the objects were simultaneously presented for 40 seconds (10 seconds for each of the four objects). In all conditions, each object was labeled 3 times (e.g., “Look at this fep!”). In the simultaneous condition, children were provided with one invitation to compare as the first labeling event (e.g., “These are all feps.”). Thus, the number of times the objects were labeled was equated across conditions.

Test Phase

During the test phase, children were given one forced choice test. For children in the immediate testing condition, the test phase immediately followed the learning phase. For children in the 15 minute delay condition, the test phase occurred exactly 15 minutes following the learning phase. As depicted in Figure 1 (Panel C), children were simultaneously presented with four objects, in random placement order, and were asked to pick out the target object (“Can you hand me the fep?”). One of the four objects, the target object (e.g., “fep”), was a new instance of the category that varied in color and texture from previously viewed instances. A second object was the distractor item that had been presented during the distractor phase. A third object was an unfamiliar novel object and the fourth object was an object known by children that had not been presented during the experiment (e.g., a toy dog). Children were not given feedback after making their selection.

In the immediate condition, testing immediately followed the distractor and learning phases. In the delayed condition, learning and distractor phases were interleaved. For example, after the distractor and learning phases for the first trial were complete, the distractor and learning phases for the second trial immediately followed, and so on until children had completed all learning and distractor phases. Testing for each trial occurred exactly 15 minutes following the end of the corresponding learning phase. A 15 minute delay was chosen because (a) it required children to access information from long-term memory and (b) it was short enough to allow children to be able to pay attention for the entire experiment.

Results and Discussion

We first asked whether the timing of presentation affected children’s in-the-moment and long-term generalization. Figure 2 shows the mean number of correct responses in the six conditions of the study. As can be seen in the figure, there were overall differences between the two testing delay conditions and the three presentation timing conditions, suggesting an interaction between delay and presentation timing. A 3 (Presentation Timing) × 2 (Testing Delay) ANOVA, with the number of correct responses as the dependent measure, confirmed a significant main effect of delay, F(1, 66) = 67.456, p < .001, ηp2 = .505; a main effect of presentation timing, F(2, 66) = 5.620, p = .006, ηp2 = .146; and an interaction of delay and presentation timing, F(2, 66) = 23. 747, p < .001, ηp2 = .418.

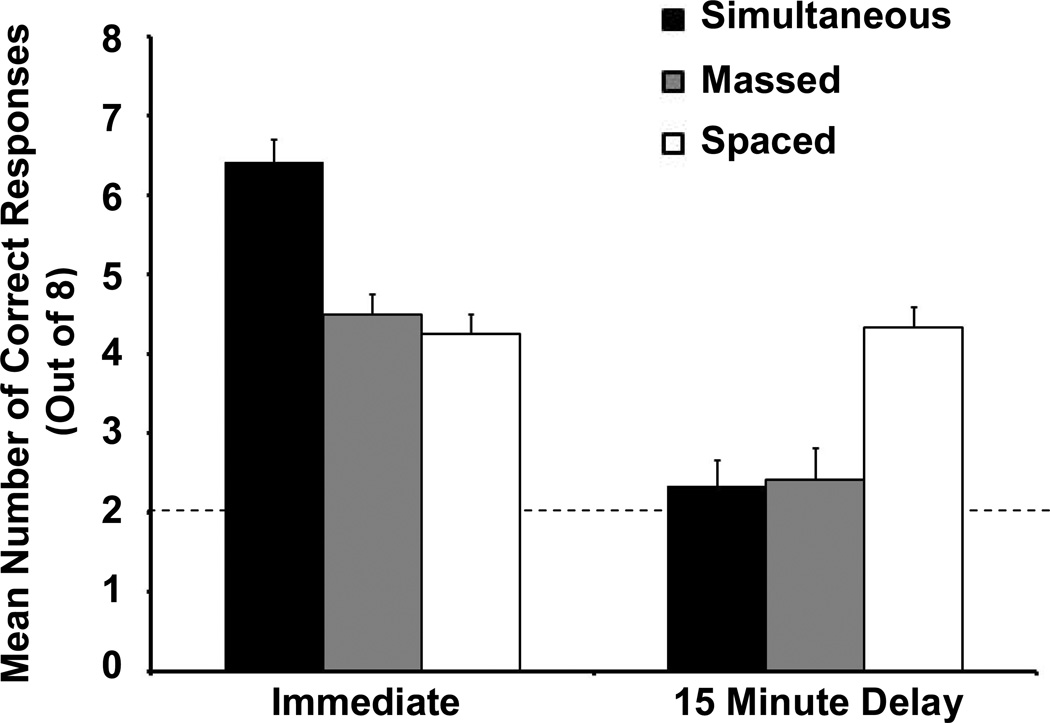

Figure 2.

Results final test performance in Experiment 1. Mean number of correct responses (out of a possible eight) by testing delay condition (immediate or 15 minute delay) and presentation timing condition (simultaneous, massed, or spaced). Error bars represent standard errors. The dashed line represents chance performance (2 out of 8 correct). At the 15 minute delay test, only children in the spaced condition performed above chance.

Post-hoc analyses were used to examine the interaction between testing delay and presentation timing. First, two planned univariate ANOVAs were conducted, one within each testing delay condition (immediate and 15 minute delay). We then computed three planned comparisons using t-tests with Bonferroni corrections (corrected to an alpha of .05, p < .05/3) to determine the nature of the differences between presentation timing within the particular testing delay condition.

These post hoc tests revealed that there were significant differences in performance between presentation timing conditions on both the immediate and delayed test. When tested immediately, children’s performance in the simultaneous condition was significantly higher than in the massed condition, p = .002, and spaced condition, p = .001. There was not a significant difference between the massed and spaced conditions, p > .05. Performance in all conditions was significantly higher than chance performance (2 out of 8 correct).

However, when tested 15 minutes later, tests revealed a different pattern of results. Children’s performance in the spaced condition was significantly higher than in the simultaneous condition, p < .001, and massed condition, p < .001. There was no significant difference between the simultaneous and massed conditions, p > .05, and they were not significantly different from chance (2 out of 8 correct), p > .05.

We also examined the possibility that children’s productive vocabulary influenced performance. In order to examine this possibility, children’s MCDI score was added to the analyses above as a covariate. However, this analysis revealed the same pattern of results and MCDI score was not a significant covariate, F(1, 65) = .436, p > .05. Thus, it is unlikely that children’s vocabulary level was a primary factor in the results of this study.

This pattern of results raised several questions. First, why did performance in the in-the-moment generalization task differ across conditions? One explanation is that the brief verbal invitation to compare instances (e.g., “These are all feps.”) that was provided in the simultaneous condition led to differences in performance. This invitation to compare was originally included to be consistent with the comparison literature, which commonly provides children with a similar phrase (e.g., Christie & Gentner, 2010; Namy & Gentner, 2002). In Experiment 2, the verbal invitation to compare was not provided in the simultaneous condition and the language used by the experimenter was consistent across the conditions. Thus, Experiment 2 was designed to rule this explanation out as a possibility.

Second, why were there differences in children’s performance across the in-the-moment and long-term generalization tasks? The results of this experiment mirror findings from the literature on desirable difficulties in learning (e.g., Bjork, 1994; Roediger & Karpicke, 2006). This work argues that several conditions of learning that initially deter performance often promote long-term performance. Conversely, many conditions of learning that promote immediate performance often do not promote long-term performance.

What was desirably difficult in the spaced condition? We predicted that the answer lies in the retrieval dynamics occurring during the learning phase of the experiment. Specifically, we predicted that, in the simultaneous condition, it did not require much cognitive effort for children to retrieve and generalize the labels to objects. Because all of the instances remained visible in the simultaneous condition, children did not have to recall previous instances. However, in the spaced condition, children were required to recall the instances that had previously been presented. Indeed, more effortful retrieval conditions during learning have been shown to promote long-term performance (often termed “retrieval effort hypothesis”; see, Karpicke & Roediger, 2007; Pyc & Rawson, 2009). In Experiment 2, we examined the retrieval dynamics occurring during the learning phase to determine if there were differences in ease of retrieval during learning.

Experiment 2

There were two goals of the current experiment. First, we sought to determine whether the benefit of simultaneous presentations was present in the in-the-moment generalization task when children were not provided with a verbal invitation to compare instances (e.g., “These are all feps.”). Second, we sought to discover a mechanism underlying the presentation conditions that could be contributing to differences in performance across time. Specifically, we predicted that varying degrees of retrieval difficulty during learning could be contributing to performance on both the in-the-moment and long-term generalization task.

Method

Participants

The participants were 72 2- to 2.5-year-old children (M = 27.1 months, range: 24–30 months). Half of the children were randomly assigned to immediate testing and the other half were assigned to 15 minute delayed testing. An equal number of children were randomly assigned to each presentation condition (simultaneous, massed, and spaced), resulting in 12 children in each condition of the study. Across conditions, there were no significant differences in age and there were an equal number of boys and girls in each condition.

All children were monolingual English speakers and recruited from a child participant database and local preschools. Only children in which parents reported no family history of color blindness were recruited. In order to ensure that children’s productive vocabulary was equivalent across experimental conditions, parents completed the MacArthur Bates Communicative Development Inventory: Words & Sentences (MCDI) (Fenson, et al., 1994). Productive vocabulary did not differ significantly across the experimental conditions, F(1, 66) = .888, p > .05 (M = 452 words, range: 292 – 656, for all children).

Stimuli

Same as Experiment 1.

Design and Procedure

The design and procedure were the same as Experiment 1, with three exceptions. First, in the simultaneous condition, the experimenter did not provide the verbal invitation to compare learning instances (“These are all feps.”). Thus, the language was consistent across the three learning conditions. Second, the experimenter presented children with a brief pre-experiment retrieval task in order to ensure that they would be able to label objects during the learning phase. Finally, during the learning phase of all trials, the experimenter asked children to retrieve and generalize the label for the instances in presentations 2–4.

Pre-experiment retrieval task

In order to ensure that children would be able to understand the experimenter’s instructions and retrieve labels during the learning phase, a brief task was administered before the experiment. In this task, children were simultaneously presented with familiar objects, specifically a toy flower and a toy orange. The experimenter pointed to one of the objects and asked children to recall the name of the object (e.g., “What is this called?”). After the child responded, the experimenter then pointed to the second object and asked children to recall the name of the object (e.g., “What is this called?”). All children were able to successfully tell the experimenter the label for the flower and orange.

Retrieval task during learning phase

In each trial, children were asked to retrieve the label for objects in presentations 2–4 of the learning phase. For example, in the massed condition, children were first shown an instance of the target category, which was labeled three times (e.g., “Look at this fep!”). The experimenter then removed the first object from the table and presented children with the second instance from that same category. The experimenter pointed to the object and asked children to retrieve the label (e.g., “What is this called?”). It is important to note that the experimenter asked this question before labeling the second instance. Children were given five seconds to respond and any response was recorded by the second experimenter. Regardless of children’s response/lack of response, after five seconds (i.e., half of the presentation time) the experimenter labeled the instance three times (e.g., “Look at this fep!”). The same label retrieval procedure in the second instance presentation was used for the third and fourth instances and in all of the presentation conditions (e.g., simultaneous, massed, and spaced).

Results and Discussion

Overall Performance at Test

We started our analysis by examining overall performance at test. We were interested in determining if the overall pattern of performance would replicate when children were not provided with a verbal invitation to compare the instances in the comparison condition. Figure 3 shows the mean number of correct responses in the six conditions of the study. As can be seen in the figure, there were overall differences between the two testing delay conditions and the three presentation timing conditions, suggesting an interaction between delay and presentation timing. A 3 (Presentation Timing) × 2 (Testing Delay) ANOVA, with the number of correct responses as the dependent measure, confirmed a significant main effect of delay, F(1, 66) = 43.360, p < .001, ηp2 = .396; a main effect of presentation timing, F(2, 66) = 7.917, p = .001, ηp2 = .193; and an interaction of delay and presentation timing, F(2, 66) = 17. 968, p < .001, ηp2 = .353.

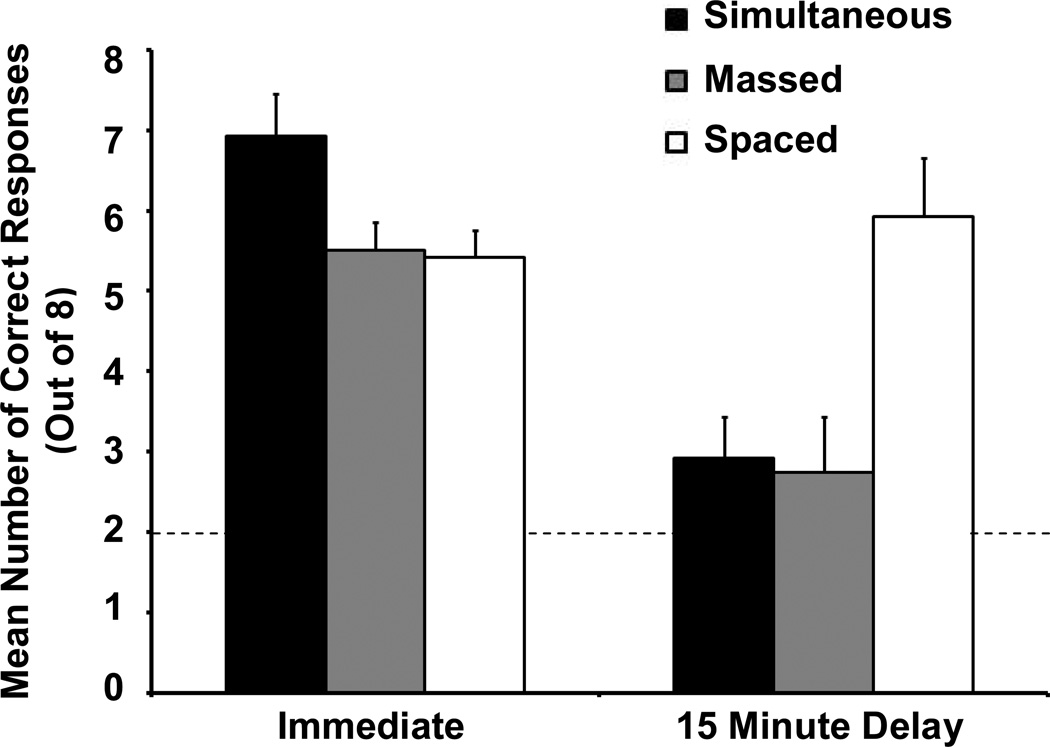

Figure 3.

Results of final test performance in Experiment 2. Mean number of correct responses (out of a possible eight) by testing delay condition (immediate or 15 minute delay) and presentation timing condition (simultaneous, massed, or spaced). Error bars represent standard errors. The dashed line represents chance performance (2 out of 8 correct). Children in all conditions performed significantly above chance.

Post-hoc analyses were used to examine the interaction between testing delay and presentation timing. First, two planned univariate ANOVAs were conducted, one within each testing delay condition (immediate and 15 minute delay). We then computed three planned comparisons using t-tests with Bonferroni corrections to determine the nature of the differences between presentation timing within the particular testing delay condition.

These post hoc tests revealed that there were significant differences in performance between presentation timing conditions on both the immediate and delayed test. When tested immediately, children’s performance in the simultaneous condition was significantly higher than in the massed condition, p = .053, and spaced condition, p = .047. There was not a significant difference between the massed and spaced conditions, p > .05. Performance in all conditions was significantly higher than chance performance (2 out of 8 correct). Thus, the benefit of simultaneous presentations for in-the-moment learning that was seen in Experiment 1 was replicated in this experiment.

In the 15 minute delayed generalization task, analyses also revealed a similar pattern of results to that of Experiment 1. Children’s performance in the spaced condition was significantly higher than in the simultaneous condition, p < .001, and massed condition, p < .001. There was no significant difference between the simultaneous and massed conditions, p > .05. Performance in all conditions was significantly higher than chance performance (2 out of 8 correct).

We also examined the possibility that children’s productive vocabulary influenced performance at test. In order to examine this possibility, children’s MCDI score was added to the analyses above as a covariate. However, this analysis revealed the same pattern of results and MCDI score was not a significant covariate, F(1, 65) = 1.450, p > .05. Thus, it is unlikely that children’s vocabulary level was a primary factor in the test performance results.

In sum, the overall pattern from the Experiment 1 was replicated in Experiment 2. When comparing the results across studies (see Figures 2 and 3), it appeared that performance in Experiment 2 was higher than performance in Experiment 1. A 2 (Experiment) × 3 (Presentation Timing) × 2 (Testing Delay) ANOVA, with the number of correct responses as the dependent measure, confirmed a significant main effect of experiment, F(1, 132) = 26.694, p < .001, ηp2 = .122, and no significant interactions, ps >.05. Thus, children in Experiment 2 performed higher overall than children in Experiment 1. This effect is likely a result of the fact that children were explicitly asked to retrieve and generalize labels during the learning phase of Experiment 2. Indeed, these results are consistent with the literature on the generation effect (see Bertsch, Pesta, Wiscott, & McDaniel, 2007, for a meta-analysis) demonstrating that there is higher performance when learners are asked generate information during learning.

Retrieval Performance

We were interested in determining if there were different retrieval dynamics occurring in the three presentation conditions that could be contributing to differences in test performance. During each trial, children were asked to retrieve the category label a total of three times (once on the second presentation, once on the third presentation, and once on the fourth presentation). Thus, across the eight learning trials, there were 24 retrieval events where the experimenter asked children to label an object.

We first examined the overall number of retrieval successes during the learning phase. A retrieval success was coded as correctly producing the object label during the first 5s of the presentation (before the experimenter labeled the object) with the word that had been provided by the experimenter on the first presentation of that learning trial. As can be seen in Figure 4 (left figure), there appeared to be differences in the overall number of retrieval successes in each of the conditions. A univariate ANOVA, with the overall number of retrieval successes during the learning phase as the dependent measure, confirmed a significant main effect of presentation timing, F(2, 69) = 76.563, p < .001, ηp2 = .689. Post-hoc analyses with Bonferroni corrections revealed that children’s scores in the simultaneous condition were significantly higher than children’s scores in the massed and spaced conditions, ps < .001. Children’s scores in the massed condition were significantly higher than children’s scores in the spaced condition, p < .001.

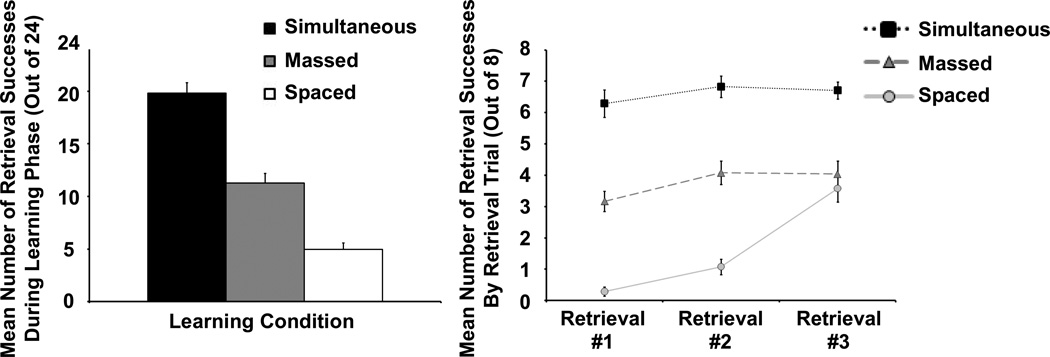

Figure 4.

Results of the retrieval task during the learning phase of Experiment 2. The figure on the left represents the mean number of retrieval successes, by presentation timing condition (simultaneous, massed, or spaced). The figure on the right represents the mean number of retrieval successes by retrieval event (first retrieval event at second presentation, second retrieval event at third presentation, and third retrieval event at fourth presentation) and presentation timing condition (simultaneous, massed, and spaced). Error bars in both figures represent standard errors.

We next examined children’s pattern of retrieval successes across the presentations of category instances. Specifically, we examined the total number of retrieval successes, in each retrieval event, during the learning trial (once on the second presentation, once on the third presentation, and once on the fourth presentation). As can be seen in Figure 4 (right figure), there were differences in the patterns of retrieval successes across the learning trial. A mixed 3 (Presentation Timing)×3 (Retrieval Event) ANOVA confirmed a significant main effect of presentation timing, F(2, 69) = 76.563, p < .001, ηp2 = .689; a main effect of retrieval event, F(1, 69) = 50.108, p < .001, ηp2 = .421; and an interaction of presentation timing and retrieval event, F(2, 69) = 17.074, p < .001, ηp2 = .331.

The pattern of performance suggested that children in the simultaneous and massed conditions showed consistent retrieval performance across presentations of each learning trial (see Figure 4). However, children in the spaced condition had lower performance on the first retrieval event but appeared to improve across presentations. To examine whether children demonstrated differing retrieval performance across conditions, we conducted planned comparisons of retrieval events within each presentation condition using Bonferroni corrections. Results confirmed that, for children in the simultaneous condition, there were no significant differences between retrieval events, ps> .05. Children in the massed condition had a marginally higher number of retrieval successes at the second retrieval event compared to the first retrieval event, p = .087, but there was not a significant differences in performance between the first and third retrieval events, as well as the second and third retrieval events, ps > .05.

In contrast, children in the spaced condition had significant differences in the number of retrieval successes between each retrieval event. Children’s performance was significantly higher at the second retrieval event than the first retrieval event, p = .001, and significantly higher at the third retrieval event than the second retrieval event, p < .001. In sum, these analyses revealed that (a) there were differences in the overall number of retrieval successes across the three presentation conditions, and, (b) children in the spaced condition had a different pattern of performance across retrieval events than children in the simultaneous and massed conditions.

We also examined the possibility that children’s productive vocabulary influenced retrieval performance. In order to examine this possibility, children’s MCDI score was added to the analyses above as a covariate. However, this analysis revealed the same pattern of results and MCDI score was not a significant covariate, F(1, 68) = .020, p > .05. Thus, it is unlikely that children’s vocabulary level was a primary factor in the retrieval task performance results.

In sum, these results suggest that retrieval was the easiest in the simultaneous condition and the most difficult in the spaced condition. Children in the simultaneous and massed conditions had consistent retrieval performance across presentations, whereas children in the spaced condition improved across presentations. These retrieval dynamics, both the overall number and pattern of retrieval successes, may be contributing to differences in performance in the in-the-moment and long-term generalization tasks. We discuss this possibility in the General Discussion section.

General Discussion

In these experiments, we set out to examine an inconsistent set of results: how is that both the presentation of instances at the same time and the presentation of instances apart in time can facilitate long-term generalization? We found that when tested immediately, children had higher performance on a generalization task when instances were presented at the same time (simultaneous) rather than presented sequentially (massed) or across time (spaced). However, when tested just 15 minutes later, children had higher performance when instances were presented across time (spaced) than when presented at the same time (simultaneous) or sequentially (massed).

In Experiment 2, we examined ease of retrieval as a mechanism underlying the differences in performance on the final test. Indeed, we found differences in children’s ability to retrieve and generalize words to objects during learning. Overall, children that were presented with instances at the same time (simultaneous) successfully retrieved more labels than children in the other conditions. Furthermore, children that were presented with instances across time (spaced) had a markedly different pattern of retrieval successes across learning trials. These results have implications for several theories of learning, which are discussed below.

In-the-Moment Generalization

When we assessed children’s generalization in the moment that they first encountered the instances, we found that performance was higher in the simultaneous condition than in the other conditions. This finding is consistent with a large body of research on comparison showing benefits of simultaneous presentations for in-the-moment generalization (e.g., Gentner et al., 2009; Namy & Gentner, 2002; Oakes & Ribar, 2005). Why was there a benefit of simultaneous presentations at the immediate test? Theories of comparison have proposed that simultaneous presentations promote the abstraction of similarities and differences because learners are more readily able to find structural and relational similarities between instances. For example, Gentner’s structure mapping theory of comparison (e.g., Christie & Gentner, 2010; Gentner et al., 2009; Namy & Gentner, 2002) proposes that the process of aligning two representations can result in the extraction of common structures that are not readily evident within either item alone.

What allowed learners to engage in the mental process of comparison to a greater degree in the simultaneous condition? We propose that the reduced degree of forgetting and memory demands in the simultaneous presentation condition may have provided the opportunity for learners to engage in the mental process of comparison during learning. Because all of the instances remained visible during the learning phase, children in the simultaneous condition did not have to think back in time to recall the previous instances that they had seen. Moreover, children were not provided time to forget previous instances between presentations.

Indeed, the results from Experiment 2 support this proposal. Children in the simultaneous condition had the overall highest number of retrieval successes and a uniformly high number of retrieval successes across learning, compared to the massed and spaced conditions. This suggests that children were experiencing a greater ease of retrieval, a result of reduced memory demands. Although relieving learners of memory demands may support the mental process of comparison and in-the-moment generalization, it may also come at a cost at later points in time.

In-the-Moment and Long-Term Generalization

Surprisingly, after a 15 minute delay, there was no longer a benefit of simultaneous presentations. Instead, performance in the spaced condition was higher than the simultaneous and massed conditions. Why did children in the spaced condition have higher performance after a 15 minute delay? One explanation comes from the task demands of the 15 minute delayed test. In the delayed test condition, children had to retain eight target categories between learning and test. In the immediate test condition, children only had to retain one target category between learning and test. It could be that the benefits of spacing require intervening learning of other categories in order to be beneficial. Although the current experiments cannot rule out this possibility, prior research has demonstrated that the benefits of spacing for generalization are present when the task requires that only one target category be retained until test (Vlach et al., 2008). Thus, it is unlikely that this explanation could account for the results in the current experiments.

An account that is supported by both the current results and prior research is that, in the spaced condition, the interval between presentations allowed time for forgetting (e.g., Ebbinghaus, 1885/1964). Because forgetting occurred, retrieving prior presentations became more difficult. Indeed, in Experiment 2, children in the spaced condition had a lower number of retrieval successes than children in the simultaneous and massed conditions. This suggests that children in the spaced condition were experiencing a greater difficulty in retrieving information.

However, this difficulty may have caused children in the spaced condition to engage in deeper retrieval, strengthening the future retrievability of both the prior and current presentations and in turn slowing the rate of future forgetting (for models of this phenomenon in memory tasks, see Cepeda et al., 2008; Pavlik & Anderson, 2008). In Experiment 2, children in the spaced condition demonstrated improvement in retrieval success across the learning trial. Children in the simultaneous and massed conditions did not demonstrate this pattern of learning. Thus, the act of struggling to recall past instances engendered by spaced learning may have improved the retrievability of information over time, both during learning and 15 minutes later.

This proposal suggests that spaced learning allows time for forgetting and in turn promotes long-term retention by engaging learners in retrieval during subsequent learning presentations (see study-phase retrieval theory, e.g., Thios & D’Agostino, 1976; Delaney, Verkoeijen, & Spirgel, 2010). Moreover, a recent extension of study-phase retrieval theories of the spacing effect has proposed that forgetting may play a particularly important role in abstraction (Vlach et al., 2008). Forgetting promotes abstraction by supporting the memory of relevant features of a category and deterring the memory of irrelevant features of a category. For example, imagine that an infant encounters a golden retriever on one day and then later in the week encounters a black lab. When encountering the black lab, the infant is cued to retrieve similar information from past experiences, such as the number of legs and body shape of the golden retriever. This process increases the retrieval strength of these relevant features. Consequently, the future forgetting of these relevant features slows. However, irrelevant features, such as the color of the dog’s hair, are not likely to be retrieved from the experience of the golden retriever. Because of this, these irrelevant features continue to be forgotten and at a faster rate than relevant features that were retrieved from prior experiences. Thus, when the infant encounters a novel dog one month later, the infant will have a stronger memory for relevant features of the category ‘dog’ than the irrelevant features, supporting the appropriate generalization of the category ‘dog’ to the novel creature.

The current results support the idea that forgetting promotes abstraction. Moreover, this study also expands this idea by identifying the parameters under which forgetting is likely to promote generalization. Forgetting occurs over the passage of time and thus, unless a significant amount of time has passed, the process of forgetting is not likely to support abstraction and generalization.

On a final note, it is important to point out that this account of the results is also consistent with several broader theories of how learning and performance vary across time, such as fuzzy-trace theory (e.g., Brainerd & Reyna, 2004) and desirable difficulties in learning (e.g., Bjork, 1994; Roediger & Karpicke, 2006). Many learning conditions that promote immediate performance often do not promote long-term performance. On the other hand, conditions that deter in-the-moment performance often optimize long-term performance.

Implications for Theory and Research on Word Learning

The task in these experiments was a novel noun generalization task and thus the present results have implications for theory and research on word learning. First, the current results bring to light the intimate relationship between word learning and memory. Memory is a critical factor in word learning, both during category formation and at recall. The relationship between word learning and memory in this study contributes to an expanding body of literature (e.g., Sandhofer & Doumas, 2008; Vlach et al., 2008) suggesting that many aspects of word learning rely on domain-general processes of learning.

Second, this study highlights the importance of examining word learning both in the moment and over long periods of time. Current models of word learning and generalization have largely focused on in-the-moment generalization—and for a good reason. Exploring in-the-moment generalization informs our understanding of the initial encoding of the representation and thus is critical for understanding how words and categories are learned and later generalized. However, in real world learning situations, there is typically a considerable delay between the initial encoding of a representation and subsequent learning events. Thus, in order to account for the development of children’s word learning, research should incorporate testing over longer time-scales—over the course of days, months, and years.

The current research makes this point by demonstrating that immediate performance does not necessarily reflect performance at a later time. Consequently, theories of word learning should be more cautious about generalizing the results of an immediate test to longer trajectories. Instead, research should impose a delayed test in order to demonstrate the long-term mechanisms of word learning.

Conclusion and Future Directions

The process of long-term generalization is central to cognition. Successful long-term generalization is likely to be a delicate balance between the processes of abstraction, retention, and generalization. Future research should continue to examine the conditions of learning that support all three of these processes as they occur in parallel. Although different areas of research on cognition have merged by examining long-term generalization, research on the interactions of abstraction, retention, and generalization on in-the-moment generalization is another promising area of research.

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert Bjork, Nate Kornell, and Mariel Kyger for their feedback on this paper. We also thank the undergraduate research assistants of the Language and Cognitive Development Lab for their contribution to this project. Furthermore, we appreciate all of the help from the staff, parents, and children that participated in this study. The research in this paper was supported by NICHD grant R03 HD064909-01.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/xlm

References

- Bertsch S, Pesta BJ, Wiscott R, McDaniel MA. The generation effect: A meta-analytic review. Memory & Cognition. 2007;35:201–210. doi: 10.3758/bf03193441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjork RA. Memory and metamemory considerations in the training of human beings. In: Metcalf J, Shimura AP, editors. Metacognition: Knowing about knowing. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1994. pp. 185–205. [Google Scholar]

- Brainerd CJ, Reyna VF. Fuzzy-trace theory and memory development. Developmental Review. 2004;24:396–439. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepeda NJ, Pashler H, Vul E, Wixted JT, Rohrer D. Distributed practice in verbal recall tasks: A review and quantitative synthesis. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:354–380. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.3.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepeda NJ, Vul E, Rohrer D, Wixted JT, Pashler H. Spacing effects in learning: A temporal ridgeline of optimal retention. Psychological Science. 2008;19:1095–1102. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie S, Gentner D. Where hypotheses come from: Learning new relations by structural alignment. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2010;11:356–373. [Google Scholar]

- Delaney PF, Verkoeijen PJ, Spirgel A. Spacing and testing effects: A deeply critical, lengthy, and at times discursive review of the literature. The Psychology of Learning and Motivation: Advances in Research and Theory. 2010;53:63–147. [Google Scholar]

- Ebbinghaus H. In: Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology. Ruger HA, Bussenius CE, Hilgard ER, translators. New York: Dover Publications; 1964. (Original work published in 1885). [Google Scholar]

- Fenson L, Dale PS, Reznick JS, Bates E, Thal DJ, Pethick SJ. Variability in early communicative development. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1994;59(5, serial 242) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentner D, Loewenstein J, Thompson L, Forbus KD. Reviving inert knowledge: Analogical abstraction supports relational retrieval of past events. Cognitive Science: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2009;33:1343–1382. doi: 10.1111/j.1551-6709.2009.01070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpicke JD, Roediger HL., III Repeated retrieval during learning is the key to long-term retention. Journal of Memory and Language. 2007;57:151–162. [Google Scholar]

- Kornell N, Bjork RA. Learning concepts and categories: Is spacing the “enemy of induction“? Psychological Science. 2008;19:585–592. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovack-Lesh KA, Oakes LM. Hold your horses: How exposure to different items influences infant cognition. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2007;98:69–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namy LL, Gentner D. Making a silk purse out of two sow’s ears: Young children’s use of comparison in category learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2002;131:5–15. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.131.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakes LM, Ribar RJ. A comparison of infant’s categorization in paired and successive presentation familiarization tasks. Infancy. 2005;7:85–98. doi: 10.1207/s15327078in0701_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlik PI, Jr, Anderson JR. Using a model to compute the optimal schedule of practice. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied. 2008;14:101–117. doi: 10.1037/1076-898X.14.2.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyc MA, Rawson KA. Testing the retrieval effort hypothesis: Does greater difficulty correctly recalling information lead to higher levels of memory? Journal of Memory and Language. 2009;60:437–447. [Google Scholar]

- Roediger HL, III, Karpicke JD. Test-enhanced learning: Taking memory tests improves long-term retention. Psychological Science. 2006;17:249–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandhofer CM, Doumas LAA. Order of presentation effects in learning color categories. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2008;9:194–221. [Google Scholar]

- Star JR, Rittle-Johnson B. It pays to compare: An experimental study on computational estimation. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2009;102:408–426. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thios SJ, D’Agostino PR. Effects of repetition as a function of study-phase retrieval. Journal of Verbal Learning & Verbal Behavior. 1976;15:529–536. [Google Scholar]

- Vlach HA, Sandhofer CM, Kornell N. The spacing effect in children’s memory and category induction. Cognition. 2008;109:163–167. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]