Abstract

Background

Cachexia is a multiorganic syndrome associated with cancer, characterized by body weight loss, muscle and adipose tissue wasting and inflammation.

Methods

The aim of this investigation was to examine the effect of the soluble receptor antagonist of myostatin (sActRIIB) in cachectic tumor-bearing animals analyzing changes in muscle proteolysis and in quality of life.

Results

Administration of sActRIIB resulted in an improvement in body and muscle weights. Administration of the soluble receptor antagonist of myostatin also resulted in an improvement in the muscle force.

Conclusions

These results suggest that blocking myostatin pathway could be a promising therapeutic strategy for the treatment of cancer cachexia.

Keywords: Myostatin, Cancer cachexia, Skeletal muscle, Physical activity, Muscle force, Ubiquitin

Introduction

Cachexia is a multiorganic syndrome associated with cancer, characterized by body weight loss (at least 5%), muscle and adipose tissue wasting and inflammation, being often associated with anorexia [1]. The abnormalities associated with cachexia include alterations in carbohydrate, lipid, and protein metabolism [1–3]. In advanced malignant diseases, cachexia appears to be one of the most common systemic manifestations. The presence of cachexia always implies a poor prognosis, having a great impact on the patients' quality of life and survival [4]. Several important molecular mechanisms have been shown to be involved in the increased muscle catabolism observed in cancer-induced cachexia, such as greater ubiquitin–proteasome-dependent proteolysis, apoptosis, and activation of uncoupling proteins [2, 5–7]. Interaction of these mechanisms leads to muscle-mass loss by promoting protein and DNA breakdown and energy inefficiency.

Myostatin, also known as GDF-8 (growth and differentiation factor-8), is a member of the TGF-b superfamily of secreted growth factors and is a negative regulator of skeletal muscle development [8–10]. During embryogenesis, myostatin expression is restricted to developing skeletal muscles, but the protein is still expressed and secreted by skeletal muscles in adulthood [11, 12]. Mice and cattle with genetic deficiencies in myostatin exhibit dramatic increases in skeletal muscle mass, therefore supporting the role of myostatin in suppressing muscle growth [13]. Myostatin acts systemically (it is produced in muscle, adipose tissue, and heart [14] and released to the circulation) and binds to cell-surface receptors causing muscle loss. The myostatin protein circulates in the blood in a latent form as a full-length precursor that is cleaved into an amino-terminal pro-peptide and a carboxy-terminal mature region, which is the active form of the molecule. Once activated, myostatin has high affinity for the activin IIB receptor (Acvr2b, also known as ActRIIB) and weak affinity for Acvr2a (also known as ActRII and ActRIIA), both of which, like other receptors for TGF-β family members, bind multiple ligands [15, 16]. Liu et al. used a myostatin anti-sense RNA and found that the oligonucleotides could suppress myostatin expression in vivo resulting in an increase in muscle growth both in healthy and cachectic mice [17]. Interestingly, the effect of the RNA oligonucleotides was a significant upregulation of MyoD expression, therefore reinforcing the role of this transcription factor in muscle wasting [18, 19]. Although the use of the deacetylase inhibitors to increase the levels of follistatin (an antagonist of myostatin) has not lead to any positive results in the treatment of cachexia in experimental animals [20, 21], the use of the activin receptor extracellular domain/Fc fusion protein (ACVR2B-Fc) has been shown to be effective in the treatment of muscle wasting in tumor-bearing animals [21]. Finally, and very recently, Zhou et al. have shown that the administration of a high-affinity activin type II receptor leads to prolonged survival in tumor-bearing mice [22]. This receptor regulates the expression of target genes through to a TGFβ pathway. Myostatin signaling acts through this receptor in skeletal muscle by setting in motion an intracellular cascade of events involving SMAD proteins, p38 MAPK, ERK1/2, PI3-K/AKT, and Wnt pathways [23–26].

Bearing all this in mind, the objective of the present investigation was to analyze in animals bearing the Lewis lung carcinoma the effects of ActRIIB antagonism on both muscle weights and force.

Material and methods

Animals

C57Bl/6 male mice (Criffa, Barcelona, Spain), of about 20 g were used in the different experiments. The animals were maintained at 22 ± 2°C with a regular light–dark cycle (light on from 08:00 a.m. to 08:00 p.m.) and had free access to food and water. The diet (Panlab, Barcelona, Spain) consists of 54% carbohydrate, 17% protein, and 5% fat (the residue was nondigestible material). The food intake was measured daily. All animal manipulations were made in accordance with the European Community guidelines for the use of laboratory animals.

Tumor inoculation and treatment

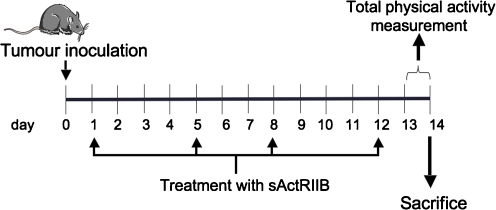

Mice received an intramuscular (hind leg) inoculum of 5 × 105 Lewis lung carcinoma cells obtained from exponential tumors. The Lewis lung carcinoma is a highly cachectic rapidly growing mouse tumor containing poorly differentiated cells, with a relatively short doubling time [27]. The animals were divided into three groups: control (C), tumor-bearing mice (TB), and tumor-bearing mice treated with the soluble receptor antagonist of myostatin (sActRIIB) [22] at the dose of 10 mg/kg s.c. twice a week (Fig. 1). sActRIIB sequesters Activin A and Myostatin in vivo [22]. At day 14, after tumor transplantation, the animals were weighed and anesthesized with a ketamine/xylacine mixture (i.p.) (Imalgene® and Rompun® respectively). The tumor was harvested from the hind leg, its volume and mass evaluated, and number of lung metastasis evaluated under the microscope. The metastases weight was evaluated according to the methodology used by Donati et al. [28]. Tissues were rapidly excised, weighed, and frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Fig. 1.

Experimental protocol

Real-time polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA from tibialis muscle was extracted by TriPureTM kit (Roche, Barcelona, Spain), a commercial modification of the acid guanidinium isothiocyanate/phenol/chloroform method [29]. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from total RNA with oligo dT15 primers and random primers pdN6 by using a cDNA synthesis kit (Transcriptor Reverse Transcriptase, Roche, Barcelona, Spain). Analysis of mRNA levels for the genes from the different proteolytic systems was performed with primers designed to detect the following gene products: ubiquitin (FORWARD 5′ GAT CCA GGA CAA GGA GGG C 3′, REVERSE 5′ CAT CTT CCA GCT GCT TGC CT3′); E2 (FORWARD: 5′ AGG CGA AGA TGG CGG T 3′; REVERSE 5′ TCA TGC CTG TCC ACC TTG TA 3′); C8 proteasome subunit (FORWARD 5′ AGA CCC CAA CAT GAA ACT GC 3′; REVERSE 5′ AGG TTT GTT GGC AGA TGC TC 3′); MuRF-1 (FORWARD 5′ TGT CTG GAG GTC GTT TCC G 3′; REVERSE 5′ ATG CCG GTC CAT GAT CAC TT 3′); Atrogin-1(FORWARD 5′ CCA TCA GGA GAA GTG GAT CTA TGT T 3′; REVERSE 5′ GCT TCC CCC AAA GTG CAG TA 3′); m-calpain (FORWARD 5′ TTG AGC TGC AGA CCA TC 3′; REVERSE 5′ GCA GCT TGA AAC CTG CTT CT 3′), cathepsin B (FORWARD 5′ CTG CTG AGG ACC TGC TTA C 3′; REVERSE 5′ CAC AGG GAG GGA TGG TGT A3′) and p0 (FORWARD 5′ GAG GTC CTC CTT GGT GAA CA 3′; REVERSE 5′ CCT CAT TGT GGG AGC AGA CA 3′). To avoid the detection of possible contamination by genomic DNA, primers were designed in different exons. The real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed using a commercial kit (LightCycler TM FastStart DNA MasterPLUS SYBR Green I, Roche, Barcelona, Spain). The relative amount of all mRNA was calculated using comparative CT method. Acidic ribosomal phosphoprotein P0 mRNA was used as the invariant control for all studies.

Total physical activity

Total physical activity (IR ACTIMETER System and ACTITRAK software from Panlab, Barcelona) was determined during the last 24 h before the sacrifice of the animals in a two subgroups of four TB mice (non-treated) and four TB mice (treated with the sActRIIB) using activity sensors that translate individual changes in the infrared pattern caused by movements of the animals into arbitrary activity counts. For the measurements, animals remained in their home cage. A frame containing an infrared beam system was placed on the outside of the cage; this minimized stress to the animals.

Grip force assessment

Skeletal muscular strength in mice was quantified by the grip strength test [30, 31]. The grip strength device (Panlab-Harvard Apparatus, Spain) comprised a triangular pull bar connected to an isometric force transducer (dynamometer). Basically, the grip strength meter was positioned horizontally and the mice are held by the tail and lowered towards the device. The animals are allowed to grasp the triangular pull bar and were then pulled backwards in the horizontal plane. The force applied to the bar just before it lost grip was recorded as the peak tension. At least three measurements were taken per mouse on both baseline and test days, and the results were averaged for analysis. This force was measured in grams/gram initial body weight.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the data was performed by means of one-way and two-way analysis of variance.

Results and discussion

The mouse Lewis lung carcinoma is a suitable model system to study the mechanisms involved in the establishment of cachexia. This tumor has been described as an anaplastic epidermoid with a marked haemorrhagic tendency, which produces multiple lung metastasis and is extremely refractory to most chemotherapeutic agents [32]. It is a well-known neoplasia that because of its fast growth rate and lung metastatic potential quickly causes death [27]. The growth of the Lewis lung carcinoma causes a rapid and progressive loss of body weight and tissue wasting, particularly in skeletal muscle [33]. Different therapeutic approaches have lead to positive results in neutralizing muscle wasting in this experimental model [34, 35], and recently a new strategy has been developed: to specifically block myostatin pathway [22].

As can be seen in Table 1, administration of sActRIIB resulted in an improvement in final body weight, the body weight increase being around 9%, while in untreated animals, the loss of weight was around 8%. This increase in body weight resulted also in an increase in carcass weight (mainly muscle and bone). Interestingly, sActRIIB treatment also resulted in an increase in food intake. Moreover, the increase in body weight affected individual muscle weights. Thus, as can be seen in Table 2, sActRIIB treatment resulted in a significant increase in gastrocnemius and tibialis muscles (31% and 36%, respectively). In fact, similar results has recently been published using the sActRIIB administration strategy in another mouse tumor model [22]. The authors concluded that in addition of an amelioration of muscle weight, treatment with the myostatin antagonist leads to prolonged survival [22]. In the rest of muscles analyzed (EDL and soleus), a clear tendency for bigger muscles as a result of treatment was observed; however, the differences did not reach statistical significance. Treatment slightly decreases the tumor weight and its volume, although it did not influence the metastatic lung area or the volume of the metastasis (Table 3).

Table 1.

Effects of sActRIIB treatment on body weights and food intake in mice bearing the Lewis lung carcinoma

| C | T | T + A | ANOVA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | ||||

| Initial body weight (g) | 19.4 ± 0.3 | 19.3 ± 0.2 | 19.2 ± 0.4 | ns | ns |

| Final body weight (g) | 19.8 ± 0.3 | 17.7 ± 0.2 | 21.0 ± 0.6 | 0.0032 | 0.0000 |

| Body weight increase (%) | −8.20% | 9.30% | |||

| Carcass | 77 ± 2 | 57 ± 0.7 | 70 ± 2.1 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Total food intake | 13.5 ± 0.2 | 11.8 ± 0.2 | 13.0 ± 0.4 | 0.0008 | 0.0053 |

Results are mean ± S.E.M. Food intake is expressed in g/100 g of initial body weight and refers to the ingestion during the period of the experiment prior to sacrifice which took place 14 days after tumor inoculation. Final body weight excludes the tumor weight. Carcass (body without organs or tumor) is expressed as g/100 g of initial body weight (IBW). Statistical significance of the results by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)

C control mice (n = 6), T tumor-bearing mice (n = 8), T + A tumor-bearing mice treated with sActRIIB (n = 8), ns nonsignificant differences, A (tumor effect), B (treatment effect)

Table 2.

Effects of sActRIIB treatment on muscle weights in mice bearing the Lewis lung carcinoma

| C | T | T + A | ANOVA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | ||||

| Gastrocnemius | 581 ± 11 | 446 ± 9 | 587 ± 15 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Tibialis | 174 ± 5 | 130 ± 4 | 177 ± 7 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| EDL | 84 ± 3 | 25 ± 3 | 31 ± 3 | 0.0000 | ns |

| Soleus | 54 ± 5 | 23 ± 2 | 28 ± 2 | 0.0000 | ns |

Results are mean ± S.E.M. Muscle weights are expressed as mg/100 g of initial body weight. Statistical significance of the results by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)

EDL extensor digitorum longus, C control mice (n = 6), T tumor-bearing mice (n = 8), T + A tumor-bearing mice treated with sActRIIB (n = 8), ns nonsignificant differences, A (tumor effect), B (treatment effect)

Table 3.

Effects of sActRIIB treatment on tumor mass and metastases in mice bearing the Lewis lung carcinoma

| T | T + A | ANOVA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor weight (mg) | 4,354 ± 213 | 3,790 ± 153 | 0.0497 |

| Tumor volume (ml) | 5.0 ± 0.33 | 4.2 ± 0.2 | 0.0492 |

| Metastases number | 6.2 ± 1.1 | 3.6 ± 0.8 | ns |

| Metastases volume | 29.9 ± 13.3 | 28.7 ± 11 | ns |

| % Lung metastases | 15.7 ± 6.7 | 19.9 ± 7.5 | ns |

Results are mean ± S.E.M. for eight animals. Statistically significant difference by post hoc Duncan test. Statistical significance of the results by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), treatment effect

T tumor-bearing mice, T + A tumor-bearing mice treated with sActRIIB, ns nonsignificant differences

Bearing in mind, the effects of the treatment on body weight and particularly in individual muscle weights, a set of experiments to measure physical performance were carried out using a physical actimeter [36]. As can be seen in Table 4, the implantation of the tumor resulted in a decrease of total physical activity (75%), mean velocity (81%), and total traveled distance (80%). Resting time was increased and the time involved in different types of movements was decreased. Similar results from our laboratory have been obtained in another tumor model [36]. As a result of the sActRIIB treatment, there was a decrease in the resting time percentage and an increase in the period of time related with slow movements (Table 4). These data suggest that sActRIIB treatment caused a slight improvement in physical performance.

Table 4.

Last 24 h of physical activity in mice bearing the Lewis lung carcinoma treated with sActRIIB

| C | T | T + A | ANOVA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | ||||

| Physical activity | |||||

| Total physical activity | 56,401 ± 531 | 14,118 ± 2,633 | 12,395 ± 1,199 | 0.0000 | ns |

| Stereotyped movements | 4,005 ± 876 | 1,245 ± 387 | 1,517 ± 330 | 0.0087 | ns |

| Locomotor movements | 52,396 ± 1,373 | 12,874 ± 2,615 | 10,878 ± 1,240 | 0.0000 | ns |

| Mean velocity | 0.32 ± 0.04 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0.0000 | ns |

| Total traveled distance | 27,455 ± 3,316 | 5,603 ± 599 | 7,979 ± 1,234 | 0.0000 | ns |

| Time | |||||

| Resting time (%) | 86.9 ± 0.5 | 95.7 ± 0.5 | 91 ± 1.8 | 0.0009 | 0.0292 |

| Slow-movements time (%) | 9.4 ± 0.7 | 4.0 ± 0.6 | 8.6 ± 1.7 | 0.0074 | 0.0173 |

| Fast-movements time (%) | 3.6 ± 0.66 | 0.3 ± 0.03 | 0.4 ± 0.12 | 0.0002 | ns |

Physical activity is expressed in activity units. Stereotyped movements include movements without displacement (eating and cleaning movements); conversely, locomotor movements include movements with displacement. Mean velocity is expressed in centimeters per second. Traveled distance is expressed in centimeters. Time is expressed as percentage of total time (24 h). The thresholds of time are the following: time involving resting (sleeping, cleaning, and eating time): [0–2] cm/s, time involving slow movements: [2–5] cm/s and time involving fast movements: [>5] cm/s. Results are mean ± S.E.M. for four animals. Statistical significance of the results by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)

C control mice, T tumor-bearing mice, T + A tumor-bearing mice treated with sActRIIB, ns nonsignificant differences, A (tumor effect), B (treatment effect)

In order to see if the increase of muscle weight and physical performance was related with increased muscle performance, grip force was determined using a specialized device dynamometer. The results presented in Table 5 clearly show an increase in muscle force as a result of sActRIIB treatment.

Table 5.

Effects of sActRIIB treatment on muscle force in mice bearing the Lewis lung carcinoma

| C | T | T + A | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grip force (day 0) | 5.1 ± 0.21a,c | 4.7 ± 0.20a,c | 5.2 ± 0.24a,c |

| Grip force (day 14) | 5.0 ± 0.23a,c | 2.8 ± 0.16b,d | 4.4 ± 0.3a,c |

Grip force is expressed as grams per gram IBW. Results are mean ± S.E.M. Statistical significance of the results by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Statistically significant difference by post hoc Duncan test. Different letters in superscript indicate significant differences between groups (a and b: differences between C, T, and T + A groups the same day of measurement; and c and d: differences between days 0 and 14 in the same group)

C control mice (n = 4), T tumor-bearing mice (n = 8), T + A tumor-bearing mice treated with sActRIIB (n = 8)

Finally, and since muscle wasting during cancer has been related with the activity of different proteolytic systems involved in enhanced muscle protein breakdown during catabolic conditions [5, 34, 37, 38], the mRNA expression levels of different genes related to proteolysis was measured following sActRIIB treatment. Indeed, tumor burden resulted in generalized increases in the majority of the components of the ubiquitin-dependent proteolytic system analyzed. An increase in m-Calpain (calcium-dependent system) and Cathepsin B (lysosomal system) were also observed in the tibialis muscle of the tumor-bearing animals (Table 6). Surprisingly, sActRIIB treatment did not influence the mRNA expression levels of the different components of the ubiquitin-dependent proteolytic system. However, sActRIIB treatment significantly decreases both calcium-dependent and lysosomal markers (Table 6). PCR real-time analysis of tibialis muscle revealed that tumor-bearing mice myostatin expression increased 1.5-fold over non-tumor bearing mice and that tumor-bearing mice treated with sActRIIB expressed similar levels of myostatin as found in non-treated tumor-bearing mice (Table 6).

Table 6.

Effects of sActRIIB treatment on tibialis muscle mRNA content of the different proteolytic systems and myostatin in mice bearing the Lewis lung carcinoma

| C | T | T + A | ANOVA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | ||||

| Proteolytic system | |||||

| Ubiquitin-dependent | |||||

| Ubiquitin | 100 ± 5 | 159 ± 9 | 152 ± 9 | 0.0001 | ns |

| C8 proteasome subunit | 100 ± 5 | 159 ± 8 | 144 ± 8 | 0.0000 | ns |

| MuRF-1 | 100 ± 24 | 207 ± 15 | 206 ± 49 | 0.0116 | ns |

| Atrogin-1 | 100 ± 24 | 266 ± 21 | 250 ± 36 | 0.0001 | ns |

| E2 | 100 ± 5 | 115 ± 5 | 108 ± 6 | ns | ns |

| Calcium-dependent | |||||

| m-Calpain | 100 ± 7 | 146 ± 6 | 107 ± 5 | 0.0001 | 0.0004 |

| Lysosomal | |||||

| Cathepsin B | 100 ± 6 | 126 ± 7 | 90 ± 8 | 0.0430 | 0.0040 |

| Myostatin | 100 ± 5 | 159 ± 9 | 152 ± 9 | 0.0158 | ns |

Results are mean ± S.E.M. for four to eight animals. The results are expressed as a percentage of controls. Statistical significance of the results by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)

C control animals, T tumor-bearing mice, T + A tumor-bearing mice treated with sActRIIB, ns nonsignificant differences, A (tumor effect), B (treatment effect)

It has to be pointed out that the calpain system could well play an important role in muscle proteolysis during cancer. From this point of view, Costelli et al. have reported an important role of calcium-dependent proteolysis both in animals [39] and humans [40]. In addition, Hasselgren et al. have attributed a key role to calpains in the early stages of muscle protein degradation [41]. Indeed, the calcium-dependent proteases participate in the release of the myofilaments from the sarcomere; these myofilaments would later be degraded by the ubiquitin-dependent proteolytic system [41]. Very recently, a role for lysosome activity in muscle degradation during cancer cachexia has been also pointed out. Indeed, activation of FoxO3 stimulates lysosomal proteolysis in muscle by activating autophagic-related genes [42]. It is well-known that FoxO3 is one of the main transcription factors involved in the activation of atrogenes, a family of genes responsible for triggering atrophy in skeletal muscle [43].

From the results presented here, it can be concluded that exploring the inhibition of the myostatin system could well be an optimal strategy, particularly in combination with a nutritional approach, for the amelioration of a cachectic syndrome in humans.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant the Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología (SAF-02284-2008). The authors of this manuscript certify that they comply with the ethical guidelines for authorship and publishing in the Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle [44]. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Evans WJ, Morley JE, Argiles J, Bales C, Baracos V, Guttridge D, et al. Cachexia: a new definition. Clin Nutr. 2008;27:793–799. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Argiles JM, Alvarez B, Lopez-Soriano FJ. The metabolic basis of cancer cachexia. Med Res Rev. 1997;17:477–498. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1128(199709)17:5<477::AID-MED3>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Argiles JM, Lopez-Soriano FJ. Why do cancer cells have such a high glycolytic rate? Med Hypotheses. 1990;32:151–155. doi: 10.1016/0306-9877(90)90039-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harvey KB, Bothe A, Jr, Blackburn GL. Nutritional assessment and patient outcome during oncological therapy. Cancer. 1979;43:2065–2069. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197905)43:5+<2065::AID-CNCR2820430714>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Argiles JM, Lopez-Soriano FJ. The ubiquitin-dependent proteolytic pathway in skeletal muscle: its role in pathological states. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1996;17:223–226. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(96)10021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanchis D, Busquets S, Alvarez B, Ricquier D, Lopez-Soriano FJ, Argiles JM. Skeletal muscle UCP2 and UCP3 gene expression in a rat cancer cachexia model. FEBS Lett. 1998;436:415–418. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)01178-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Royen M, Carbo N, Busquets S, Alvarez B, Quinn LS, Lopez-Soriano FJ, et al. DNA fragmentation occurs in skeletal muscle during tumor growth: a link with cancer cachexia? Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;270:533–537. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee SJ, McPherron AC. Myostatin and the control of skeletal muscle mass. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1999;9:604–607. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(99)00004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma M, Langley B, Bass J, Kambadur R. Myostatin in muscle growth and repair. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2001;29:155–158. doi: 10.1097/00003677-200110000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsuchida K. Targeting myostatin for therapies against muscle-wasting disorders. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2008;11:487–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McPherron AC, Lawler AM, Lee SJ. Regulation of skeletal muscle mass in mice by a new TGF-beta superfamily member. Nature. 1997;387:83–90. doi: 10.1038/387083a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elkasrawy MN, Hamrick MW. Myostatin (GDF-8) as a key factor linking muscle mass and bone structure. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2010;10:56–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee SJ. Sprinting without myostatin: a genetic determinant of athletic prowess. Trends Genet. 2007;23:475–477. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Breitbart A, Auger-Messier M, Molkentin JD, Heineke J. Myostatin from the heart: local and systemic actions in cardiac failure and muscle wasting. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300:H1973–H1982. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00200.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Caestecker M. The transforming growth factor-beta superfamily of receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2004;15:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo T, Jou W, Chanturiya T, Portas J, Gavrilova O, McPherron AC. Myostatin inhibition in muscle, but not adipose tissue, decreases fat mass and improves insulin sensitivity. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4937. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu CM, Yang Z, Liu CW, Wang R, Tien P, Dale R, et al. Myostatin antisense RNA-mediated muscle growth in normal and cancer cachexia mice. Gene Ther. 2008;15:155–160. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3303016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Costelli P, Muscaritoli M, Bossola M, Moore-Carrasco R, Crepaldi S, Grieco G, et al. Skeletal muscle wasting in tumor-bearing rats is associated with MyoD down-regulation. Int J Oncol. 2005;26:1663–1668. doi: 10.3892/ijo.26.6.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Busquets S, Deans C, Figueras M, Moore-Carrasco R, Lopez-Soriano FJ, Fearon KC, et al. Apoptosis is present in skeletal muscle of cachectic gastro-intestinal cancer patients. Clin Nutr. 2007;26:614–618. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonetto A, Penna F, Minero VG, Reffo P, Bonelli G, Baccino FM, et al. Deacetylase inhibitors modulate the myostatin/follistatin axis without improving cachexia in tumor-bearing mice. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2009;9:608–616. doi: 10.2174/156800909789057015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benny Klimek ME, Aydogdu T, Link MJ, Pons M, Koniaris LG, Zimmers TA. Acute inhibition of myostatin-family proteins preserves skeletal muscle in mouse models of cancer cachexia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;391:1548–1554. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.12.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou X, Wang JL, Lu J, Song Y, Kwak KS, Jiao Q, et al. Reversal of cancer cachexia and muscle wasting by ActRIIB antagonism leads to prolonged survival. Cell. 2010;142:531–543. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allendorph GP, Vale WW, Choe S. Structure of the ternary signaling complex of a TGF-beta superfamily member. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:7643–7648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602558103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joulia-Ekaza D, Cabello G. The myostatin gene: physiology and pharmacological relevance. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2007;7:310–315. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steelman CA, Recknor JC, Nettleton D, Reecy JM. Transcriptional profiling of myostatin-knockout mice implicates Wnt signaling in postnatal skeletal muscle growth and hypertrophy. FASEB J. 2006;20:580–582. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5125fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lokireddy S, Mouly V, Butler-Browne G, Gluckman PD, Sharma M, Kambadur R, et al. (2011) Myostatin promotes the wasting of human myoblast cultures through promoting ubiquitin-proteasome pathway-mediated loss of sarcomeric proteins. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. Sep 7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Lippman MM, Laster WR, Abbott BJ, Venditti J, Baratta M. Antitumor activity of macromomycin B (NSC 170105) against murine leukemias, melanoma, and lung carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1975;35:939–945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Donati MB, Mussoni L, Poggi A, De Gaetano G, Garattini S. Growth and metastasis of the Lewis lung carcinoma in mice defibrinated with batroxobin. Eur J Cancer. 1978;14:343–347. doi: 10.1016/0014-2964(78)90203-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Annals of Biochemistry. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sinis N, Guntinas-Lichius O, Irintchev A, Skouras E, Kuerten S, Pavlov SP, et al. Manual stimulation of forearm muscles does not improve recovery of motor function after injury to a mixed peripheral nerve. Exp Brain Res. 2008;185:469–483. doi: 10.1007/s00221-007-1174-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zangarelli A, Chanseaume E, Morio B, Brugere C, Mosoni L, Rousset P, et al. Synergistic effects of caloric restriction with maintained protein intake on skeletal muscle performance in 21-month-old rats: a mitochondria-mediated pathway. FASEB J. 2006;20:2439–2450. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4544com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henry N, van Lamsweerde AL, Vaes G. Collagen degradation by metastatic variants of Lewis lung carcinoma: cooperation between tumor cells and macrophages. Cancer Res. 1983;43:5321–5327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Llovera M, Garcia-Martinez C, Lopez-Soriano J, Agell N, Lopez-Soriano FJ, Garcia I, et al. Protein turnover in skeletal muscle of tumour-bearing transgenic mice overexpressing the soluble TNF receptor-1. Cancer Lett. 1998;130:19–27. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3835(98)00137-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Busquets S, Figueras MT, Fuster G, Almendro V, Moore-Carrasco R, Ametller E, et al. Anticachectic effects of formoterol: a drug for potential treatment of muscle wasting. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6725–6731. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Argiles JM, Lopez-Soriano FJ, Busquets S. Novel approaches to the treatment of cachexia. Drug Discov Today. 2008;13:73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Toledo M, Busquets S, Sirisi S, Serpe R, Orpi M, Coutinho J, et al. Cancer cachexia: physical activity and muscle force in tumour-bearing rats. Oncol Rep. 2011;25:189–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Costelli P, Baccino FM. Mechanisms of skeletal muscle depletion in wasting syndromes: role of ATP-ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2003;6:407–412. doi: 10.1097/01.mco.0000078984.18774.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Attaix D, Combaret L, Bechet D, Taillandier D. Role of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in muscle atrophy in cachexia. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2008;2:262–266. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e3283196ac2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Costelli P, Tullio RD, Baccino FM, Melloni E. Activation of Ca(2+)-dependent proteolysis in skeletal muscle and heart in cancer cachexia. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:946–950. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Costelli P, Reffo P, Penna F, Autelli R, Bonelli G, Baccino FM. Ca(2+)-dependent proteolysis in muscle wasting. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37:2134–2146. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hasselgren PO, Fischer JE. Muscle cachexia: current concepts of intracellular mechanisms and molecular regulation. Ann Surg. 2001;233:9–17. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200101000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao J, Brault JJ, Schild A, Cao P, Sandri M, Schiaffino S, et al. FoxO3 coordinately activates protein degradation by the autophagic/lysosomal and proteasomal pathways in atrophying muscle cells. Cell Metab. 2007;6:472–483. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sandri M, Lin J, Handschin C, Yang W, Arany ZP, Lecker SH, et al. PGC-1alpha protects skeletal muscle from atrophy by suppressing FoxO3 action and atrophy-specific gene transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:16260–16265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607795103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.von Haehling S, Morley JE, Coats AJS, Anker SD. Ethical guidelines for authorship and publishing in the Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2010;1:7–8. doi: 10.1007/s13539-010-0003-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]