Abstract

Cell adhesion plays a key role during various physiological and pathological processes. Many studies have been performed to understand the interaction of platelets with endothelial cells (ECs) during the past decades. Modulation of their interaction has been shown to be therapeutically useful in thrombotic diseases. Some methods of labeling platelets such as counting and radiolabeling have been applied in the study of the platelets-ECs interaction, but these methods did not obtain full approval. A rapid, simple and sensitive assay for platelets-ECs interaction was developed in this paper. Platelets were labeled with Sudan Black B (SBB) before adding to confluent ECs monolayer. Non-adherent platelets were removed by washing with PBS. The adherent platelets were lysed with dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and the absorbance was recorded at 595 nm by spectrophotometer. A linear correlation was observed between the absorbance of SBB and the number of platelets. By employing the SBB method, the influence of heparin on platelets-ECs interactions was observed. Heparin (3–100 units/mL) obviously reduced platelets adhering to ECs in a concentration-dependent manner.

Keywords: Adhesion assay, Platelet, Endothelial cell, Sudan Black B, Methodology

Introduction

It has been known for many years that blood platelets play an important role in hemostasis (Andrews and Berndt 2004). Platelets contribute to every aspects of hemostasis, from the initial adhesion of platelets to the vessel wall, spreading over the surface and forming a platelet aggregate, to providing an activated cell surface that vastly accelerates coagulation and leads to stabilization of the platelet aggregate by fibrin. In various diseases, platelet adhesion to the damaged vessel wall is the first step (Ruggeri 2009). Flowing platelets may adhere to specific regions of the endothelium and exposed sub-endothelial components. Rapid interactions between platelets, their secreted components, or thrombin and endothelial cells (ECs) at sites of vessel damage ensure the local secretion of mediators that prevent the intravascular growth of thrombi (Liebner et al. 2006). These multicellular interactions are essential precursors of physiologic inflammation and hemostasis. ECs make up a metabolically active interface between blood and tissue. ECs secrete a variety of molecules important for the regulation of platelet function and blood coagulation. By releasing a variety of antithrombotic components such as prostacyclin and nitric oxide, the endothelium can provide an antithrombotic surface to facilitate blood flow. However, the balance between antithrombotic and prothrombotic functions of ECs will reverse upon stimulation (Cines et al. 1998). In the normal circulation, platelets are not thought to directly adhere to intact endothelium, but there is increasing evidence that activated ECs or platelets can lead to interactions between these cells (Rosenblum 1997). Uncontrolled adhesion of platelets contributes to thrombotic disorders. In vitro, treatment of platelets or ECs with thrombin could induce platelet adhesion to endothelial monolayers (Czervionke et al. 1978; Kaplan et al. 1989).

Cell-to-cell adhesion assays are basic tools in the study of interactions between platelets and ECs. Detailed study of endothelial function first became feasible with the development in the 1970s of techniques to culture ECs in vitro (Jaffe et al. 1973). Labeled platelets are also required for cell adhesion assays. However, platelets are different from other cells because they have no karyon, survive short time in vitro and are sensitive to stimulation. Previously, adhering platelets were mainly investigated by counting binding cells visually under a microscope (Szuwart et al. 2000), or radiolabeling followed by measuring the radioactivity of adhering platelets (Curwen et al. 1982; Holme et al. 1993). The first method is less expensive and simple, but very labor-intensive. The second method is sensitive and rapid, it requires radioactive material. In this paper, a colorimetric method using Sudan Black B (SBB) to label adherent platelets was established.

Materials and methods

Isolation and culture of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs)

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were prepared according to the method described by Jaffe et al. (1973). Human umbilical vein was digested with 100 units/mL type II collagenase (Nanjing Sunshine Biotech Co., China) in M199 (Gibco, USA) for 13 min at 37 °C. Veins were flushed with warm M199, and the resulting endothelial cells suspension was centrifuged for 5 min at 250×g. Primary cultures of HUVECs were seeded into 25-cm2 flasks pre-coated with 0.02% (w/v) gelatin. Culture medium consisted of M199 supplemented with 20% (v/v) newborn calf serum (PAA Cell Culture Company, Austria), 2 mM L-glutamine, 5 units/mL penicillin G, 5 μg/mL streptomycin sulfate, 7.5 μg/mL endothelial cell growth supplement (Sigma, USA). Cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2, and the medium was changed after 24 h and every 2 days thereafter until confluent. All experiments were performed using HUVECs at passages 2 to 5.

HUVECs treatment

HUVECs harvested from culture flasks were subcultured into 48-well plates at approximately 2 × 104 cells/well incubated for about 72 h (or until complete confluence was observed) under the conditions described above. Standard heparin (176 units/mg, Sigma, USA) was added at different final concentrations of 1, 3, 10, 30, 100 units/mL. After 24 h incubation of heparin (Control wells received medium alone), TNF-alpha (BioLegend, Netherlands) at a final concentration of 10 ng/mL was added to the wells and incubated for another 24 h.

Preparation of platelets and staining with Sudan Black B

Platelets were isolated by using differential centrifugation as described by Liao et al. (2005). Human whole blood was drawn from healthy volunteers and mixed with a 1/9 volume of 3.2% sodium citrate as anticoagulant. The blood was centrifuged at 200×g for 10 min at room temperature for obtaining platelet-rich plasma (PRP). Platelets were isolated from the PRP by centrifugation at 1,000×g for 10 min. After being fixed in 4% formaldehyde/PBS for 10 min, platelets were suspended in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) at room temperature.

Filtered solution of Sudan Black B in 70% ethanol was added at volume ratio of 1:20 and platelets were allowed to stain 30 min (time from 15 to 60 min in staining experiments). After staining, the platelets were washed with PBS and centrifuged three times. Manual platelet counts were done using a hemacytometer. Finally, stained platelets were suspended at a concentration of 5 × 107 platelets/mL in PBS.

Adhesion assays

200 μL platelet suspensions were added in each test well of the 48-well plates. The platelets were allowed to adhere to ECs at 37 °C. 30 min (time from 15 to 60 min in adhering experiments) later, non-adherent platelets were removed following with a gentle wash with PBS. As to stained platelets, SBB in adherent platelets was extracted by the addition of 200 μL dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) to each well. After 20 min on a gyratory shaker, the SBB absorbance was recorded on a microplate reader spectrophotometer (Biorad Co., USA).

A correlation between absorbance and stained platelets count (from 0.5 × 104 to 1 × 105 cell numbers) was performed before adhesion assays were started. After staining for 30 min by SBB and washing three times, stained platelets were suspended at a series of concentrations (0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0 × 106 platelets/mL). 20 μL suspensions of stained platelets were added to the wells and then 180 μL DMSO was added to determine the SBB absorbance.

In order to find out whether fixation and SBB-labeling may influence platelet adhesive ability, Control platelets (not fixed and stained) were suspended at the same concentration of 5 × 107 platelets/mL as fixed platelets (not stained) and stained platelets. At the end of adhering experiments performed as described above, on each well, four microscopic fields were randomly selected and the average numbers of adherent platelets were manually counted.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate. Data were presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was evaluated by ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. The results were considered significant when p values were <0.05. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to study the relationship between SBB absorbance and stained platelets count.

Results

Optimal conditions of the adhesion assay

Absorbance spectra of SBB. The absorbance of SBB in DMSO solution peaked at 595 nm in the visible spectrum (Fig. 1). Wavelength at 595 nm was adopted in following measurements.

Linear colorimetric response. A good correlation between the absorbance of the SBB and platelets counts were obtained with a high correlation coefficient (r = 0.991). The results in Fig. 2 showed that SBB absorbance was directly proportional to platelet count from about 0.5 × 104 to 1 × 105 cells/well.

Color formation stability. Variation between SBB absorbance readings at 0, 30, 60 and 90 min was virtually eliminated (data not shown) after the correlation assay was fulfilled. SBB absorbance remained stable within at least 60 min period.

Fig. 1.

SBB absorbance spectrum. SBB was solved in DMSO and scanned in ultraviolet/visible spectroscopy. The spectrum showed the characteristic peak spectrum in the visible spectrum, which was adopted as the measuring wavelength in the following studies

Fig. 2.

Relationships of platelet counts and SBB absorbance. SBB-labeled platelets were added to plate wells in the range from about 0.5 × 104 to 1 × 105 cells/well. DMSO was added to lyse the platelets and the SBB absorbance was determined at 595 nm. The curve showed a linear relationship between platelet numbers and SBB absorbance (r = 0.991). Bars represent SD (n = 3 experiments)

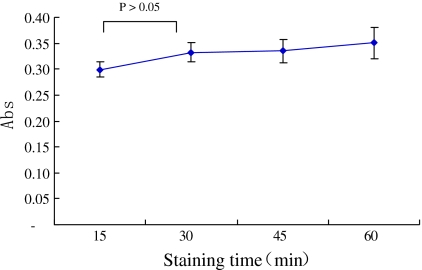

Kinetics of platelets staining and adhering

No significant changes in the SBB absorbance were observed among platelets being stained for 15, 30, 45 and 60 min (Fig. 3). Although, in the beginning, platelets were stained by SBB for 30 min, 15 min was actually long enough for SBB labeling.

Fig. 3.

Platelet SBB staining kinetics. The SBB staining time varied from 15 to 60 min. The stained platelets were suspended in PBS at the same concentration of 5 × 107 platelets/mL. The suspensions were added to plate well and the platelets were allowed to adhere to ECs for 30 min. Non-adherent platelets were removed. After washing, the adherent platelets were lysed in 200 μL DMSO. The SBB absorbance was recorded at 595 nm. Bars represent SD (n = 3 experiments)

To ascertain the time required for platelets binding to ECs, SBB-labeled platelets (for 30 min) were allowed to adhere to ECs from 15 to 60 min at 37 °C. The SBB absorbance curve began to plateau after 30 min, indicating platelet binding began to reach saturation around this point (Fig. 4). The experimental time of platelets adhering to ECs is needed at least 30 min.

Fig. 4.

Platelets adhering kinetics. Platelets were stained by SBB for 30 min and were suspended in PBS at a concentration of 5 × 107 platelets/mL. The suspensions were added to plate well and the platelets were allowed to adhere to ECs, adhering time varied from 15 to 60 min. After washing, the adhered platelets were lysed in 200 μL DMSO. The SBB absorbance was recorded at 595 nm. Bars represent SD (n = 3 experiments)

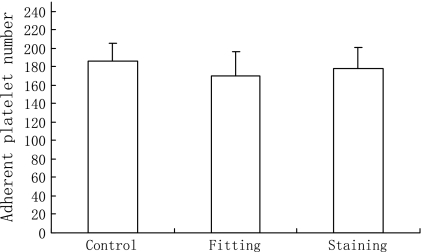

Effect of fixation and staining on platelets adhesive ability

As shown in Fig. 5, there was no significant variation in adherent counts between fixed platelets and non-fixed platelets. This result indicated that the fixation with formaldehyde did not intervene platelet adhesion. Meanwhile, the dye SBB did not influence platelet adhesive ability (Comparing to control wells, p > 0.05).

Fig. 5.

Effect of fixation and staining on platelets adhesive ability. Control platelets (not fixed and stained), fixed platelets (not stained) and stained platelets were suspended at the same concentration of 5 × 107 platelets/mL. Adhering experiments were performed using the three suspensions and adherent platelets were manually counted. Data were expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3 experiments)

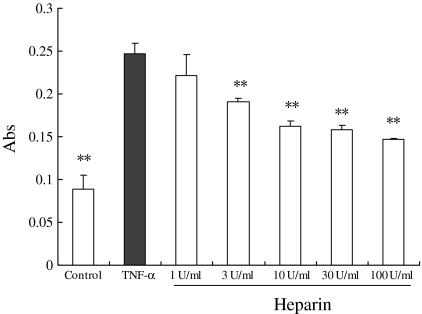

Inhibition of platelets adhesion to HUVECs by heparin

HUVECs were grown in 48-well plates and used for adhesion assays when HUVECs confluence was achieved. After the cultured ECs were treated by TNF-alpha, a large number of platelets began to adhere on the ECs (compared to the negative control, p < 0.01). Heparin (3–100 units/mL) obviously reduced platelets adhering to ECs in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Effects of heparin on platelets adhering to HUVECs. Before platelet adhesion assay, HUVECs were treated with heparin at a set of final concentrations. After 24 h incubation of heparin (Control wells received medium alone), TNF-alpha at a final concentration of 10 ng/mL was added to stimulate ECs for another 24 h. Data were expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3 experiments). ** p < 0.01 vs. TNF-alpha wells

Discussion

In this paper, we described a useful colorimetric assay for platelet-endothelial cell adhesion based on SBB labeling. Advantages offered by colorimetric labeling for determining cell number have superseded the use of radioisotopes, including the use of microplate format and increasing the number of variables which can be tested, minimizing instrument and reagent requirements, and elimination of the hazards associated with the use of radioactivity (Bellavite et al. 1994). We also tried Rose Bengal, crystal violet and methylene blue to label platelets. However, such labeling methods got very low absorbance values (data not shown). The SBB labeling was sensitive and satisfiable. The advantages of SBB colorimetric method are simplicity and convenience. The assay could be easily and quickly measured in a multiwell scanning spectrophotometer system in general laboratories.

Sudan Black B is a lysochrome dye used for staining lipids and some lipoproteins (Thakur et al. 1989). Platelets were stained blue-black with SSB. The staining method with SBB has been developed in the 1950s (Ackerman. 1952). Its staining property with platelet was studied to explore the suitability of assay methodology in this paper. The binding of SBB with platelets obeyed the law of Lambert–Beer. Tetrazolium salts are frequently used for measuring cell viability assays for its simplicity. Many laboratories worldwide have adopted this assay based on metabolic reduction of a tetrazolium dye MTT (3- (4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) (Gonzalez and Tarlor 2001). Platelets share many of the same biological characteristics as other cells. However, unlike most cells, platelets lack a nucleus and unable to adapt to changing biological settings by altered transcription. MTT test could not be used to label platelets prepared for the subsequent adhesion assay, because of cell injury by MTT formazan (Belyanskaya et al. 2007).

Heparin is well known for its anticoagulant properties. In addition, heparin possesses anti-adhesion effects. Heparin has weak inhibitory activity against platelet-collagen interactions which accounted for its non-specific interference with agonist-receptor interactions (Davies and Menys 1982). Some chemically modified heparins with low anticoagulant activities may also have potential value as therapeutic agents that block P-selectin-mediated cell adhesion (Wei et al. 2004). In this study, we found that heparin directly inhibited platelet adhering to endothelial cells. Platelets are easily activated during preparation. So performing assays to detect platelets, it is critical that artifactual stimulation of the platelets be minimized during blood collection and sample handling. In our testing, fixation of platelets prior to staining could avoid spontaneous platelet activation. Platelet fixing can make the assay more manageable (Rose et al. 1986) while did not intervene platelets adhesion.

Most hematologists are intimately familiar with the circulating platelet, but poorly informed about the endothelium. Although assays do exist for circulating markers of activated endothelium, these are indirect measures of endothelial function. In truth, endothelial cells are every bit as active as the circulating platelet. Once ECs are activated, they exhibit active interactions with platelets flowing in the marginal blood flow (Massberg et al. 1998). Platelets and ECs can communicate at multiple levels (Warkentin et al. 2003). The adhesion assay reported in this paper could be of interest since it showed simple and sensitive in studying the interactions of platelets and ECs. Superior to labor-intensive manully counting, SBB labeling method is much easier and more rapid. Comparing with radiological or fluorescent method, no special apparatus was needed in SBB measurement. Therefore, it might have potential applicability to high-throughput screening to identify specific adhesion inhibitors for anti-thrombotic drugs. Similarly, in anticancer research which is related with platelets interaction, this adhesion assay might have a wide usage.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.30600821), the Natural Science Foundation of Anhui Province (No. 050431004; No. 070413123) and the Postgraduate Innovation Project of Jiangsu Province (No. CX07B_236z).

References

- Ackerman GA. A modification of the Sudan Black B technique for the possible cytochemical demonstration of masked lipids. Science. 1952;115:629–663. doi: 10.1126/science.115.2997.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews RK, Berndt MC. Platelet physiology and thrombosis. Thromb Res. 2004;114:447–453. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2004.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellavite P, Andrioli G, Guzzo P, Arigliano P, Chirumbolo S, Manzato F, Santonastaso C. A colorimetric method for the measurement of platelet adhesion in microtiter plates. Anal Biochem. 1994;216:444–450. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belyanskaya L, Manser P, Spohn P, Bruinink A, Wick P. The reliability and limits of the MTT reduction assay for carbon nanotubes–cell interaction. Carbon. 2007;45:2643–2648. doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2007.08.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cines DB, Pollak ES, Buck CA, Loscalzo J, Zimmerman GA, McEver RP, Pober JS, Wick TM, Konkle BA, Schwartz BS, Barnathan ES, McCrae KR, Hug BA, Schmidt AM, Stern DM. Endothelial cells in physiology and in the pathophysiology of vascular disorders. Blood. 1998;91:3527–3561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curwen KD, Kim HY, Vazquez M, Handin RI, Gimbrone MA., Jr Platelet adhesion to cultured vascular endothelial cells. A quantitative monolayer adhesion assay. J Lab Clin Med. 1982;100:425–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czervionke RL, Hoak JC, Fry GL. Effect of aspirin on thrombin induced adherence of platelets to cultured endothelial cells from the vessel wall. J Clin Invest. 1978;62:841–856. doi: 10.1172/JCI109197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies JA, Menys VC. Effect of heparin on platelet monolayer adhesion, aggregation and production of malondialdehyde. Thromb Res. 1982;26:31–41. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(82)90148-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez RJ, Tarlor JB. Evaluation of hepatic subcellular fractions for Almar blue and MTT reductase activity. Toxicol In Vitro. 2001;15:257–259. doi: 10.1016/S0887-2333(01)00014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holme S, Heaton A, Roodt J. Concurrent label method with 111In and 51Cr allows accurate evaluation of platelet viability of stored platelet concentrates. Br J Haematol. 1993;84:717–723. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1993.tb03151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe EA, Nachman RL, Becker CG, Minick CR. Culture of human endothelial cells derived from umbilical veins. Identification by morphologic criteria. J Clin Invest. 1973;52:2745. doi: 10.1172/JCI107470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan JE, Moon DG, Weston LK, Minnear FL, Del Vecchio PJ, Shepard JM, Fenton JW., 2nd Platelets adhere to thrombin treated endothelial cells in vitro. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:H423–H433. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.2.H423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao CH, Cheng JT, Teng CM. Interference of neutrophil–platelet interaction by YC-1: a cGMP-dependent manner on heterotypic cell–cell interaction. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;519:157–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebner S, Cavallaro U, Dejana E. The multiple languages of endothelial cell-to-cell communication. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:1431–1438. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000218510.04541.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massberg S, Enders G, Leiderer R, Eisenmenger S, Vestweber D, Krombach F, Messmer K. Platelet-endothelial cell interactions during ischemia/reperfusion: the role of P-selectin. Blood. 1998;92:507–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose NR, Friedman H, Fahey JL. Manual of clinical laboratory immunology. 3. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology; 1986. pp. 226–235. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum WI. Platelet adhesion and aggregation without endothelial denudation or exposure of basal lamina and/or collagen. J Vasc Res. 1997;34:409–417. doi: 10.1159/000159251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggeri ZM. Platelet adhesion under flow. Microcirculation. 2009;16:58–83. doi: 10.1080/10739680802651477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szuwart T, Brzoska T, Luger TA, Filler T, Peuker E, Dierichs R. Vitamin E reduces platelet adhesion to human endothelial cells in vitro. Am J Hematol. 2000;65:1–4. doi: 10.1002/1096-8652(200009)65:1<1::AID-AJH1>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur MS, Prapulla SG, Karanth NG. Estimation of intracellular lipids by the measurement of absorbance of yeast cells stained with Sudan Black B. Enzyme Microb Technol. 1989;11:252–254. doi: 10.1016/0141-0229(89)90101-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Warkentin TE, Aird WC, Rand JH (2003) Platelet-endothelial interactions: sepsis, HIT, and antiphospholipid syndrome. Hematology 2003:497–519 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wei M, Tai G, Gao Y, Li N, Huang B, Zhou Y, Hao S, Zeng X. Modified heparin inhibits P-selectin-mediated cell adhesion of human colon carcinoma cells to immobilized platelets under dynamic flow conditions. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:29202–29210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312951200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]