Abstract

Although most investigations of the mechanisms underlying chronic pain after spinal cord injury (SCI) have examined the central nervous system (CNS), recent studies have shown that nociceptive primary afferent neurons display persistent hyperexcitability and spontaneous activity in their peripheral branches and somata in dorsal root ganglia (DRG) after SCI. This suggests that SCI-induced alterations of primary nociceptors contribute to central sensitization and chronic pain after SCI. Does SCI also promote growth of these neurons' fibers, as has been suggested in some reports? The present study tests the hypothesis that SCI induces an intrinsic growth-promoting state in DRG neurons. This was tested by dissociating DRG neurons 3 days or 1 month after spinal contusion injury at thoracic level T10 and measuring neuritic growth 1 day later. Neurons cultured 3 days after SCI exhibited longer neurites without increases in branching (“elongating growth”), compared to neurons from sham-treated or untreated (naïve) rats. Robust promotion of elongating growth was found in small and medium-sized neurons (but not large neurons) from lumbar (L3–L5) and thoracic ganglia immediately above (T9) and below (T10–T11) the contusion site, but not from cervical DRG. Elongating growth was also found in neurons immunoreactive to calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), suggesting that some of the neurons exhibiting enhanced neuritic growth were nociceptors. The same measurements made on neurons dissociated 1 month after SCI revealed no evidence of elongating growth, although evidence for accelerated initiation of neurite outgrowth was found. Under certain conditions this transient growth-promoting state in nociceptors might be important for the development of chronic pain and hyperreflexia after SCI.

Key words: calcitonin gene-related peptide, conditioning lesion, pain, primary afferent, regeneration

Introduction

Following spinal cord injury (SCI) a majority of patients develop chronic neuropathic pain below and at the injury level (Finnerup et al., 2001; Johannes et al., 2010). Although most investigations into SCI pain mechanisms have focused on neurons in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord and at higher levels in the brain (Finnerup and Jensen, 2004; Hains and Waxman, 2007; Hulsebosch et al., 2009; Yezierski, 2009), recent studies have shown that SCI also produces persistent alterations in the physiology of primary afferent neurons that may contribute to chronic pain. Carlton and associates (2009) showed that contusion injury at thoracic level T10 produces spontaneous activity (SA), and both thermal and mechanical sensitization in forelimb nociceptors recorded in an excised skin-nerve preparation. Bedi and colleagues (2010) showed that contusion at this level also produces SA in nociceptors that is generated within lumbar dorsal root ganglia (DRG) in vivo, and which continues to be expressed in nociceptor somata from lumbar and thoracic levels when the nociceptors are dissociated days to months after SCI. The occurrence of SA in somata cultured at low density 1 day after dissociation suggests that long-lasting intrinsic changes in nociceptor somata contribute to chronic pain after SCI (Bedi et al., 2010). An interesting question is whether SCI also changes the growth state of nociceptors and other primary afferents. This possibility is supported by observations suggesting that SCI can induce sprouting within the spinal cord from low-threshold primary afferent neurons (Helgren and Goldberger, 1993), and from smaller-diameter primary afferents that are immunoreactive to calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), which is found in many “peptidergic” nociceptors (Christensen and Hulsebosch, 1997; Krenz and Weaver, 1998; Krenz et al., 1999; Ondarza et al., 2003; Weaver et al., 2001). Increased densities of CGRP-IR have also been found in the thoracic dorsal horn of human SCI patients (Ackery et al., 2007). Central growth of processes from primary afferents would suggest that a potential mechanism by which SCI increases input to pain pathways is by stimulating growth of additional synaptic terminals from primary afferents onto second-order neurons in the dorsal horn, which has been suggested as a mechanism contributing to peripheral neuropathic pain (e.g., Jaken et al., 2010; Woolf et al., 1992). While many factors affect the potential for central growth of primary afferents after peripheral or central injury (see Discussion), a basic question is whether SCI enhances the intrinsic growth state of these neurons.

Peripheral nerve injury that transects DRG neurons' peripheral axons produces a “conditioning lesion” effect in axotomized DRG neurons that promotes regenerative growth of axons after a second axotomizing lesion (e.g., Neumann and Woolf, 1999; Oblinger and Lasek, 1984). In vitro, effects on DRG neurons of an earlier in vivo conditioning lesion are expressed by an acceleration of neuritic outgrowth and an elongation of neurites 1 day after dissociation (Hu-Tsai et al., 1994; Lankford et al., 1998; Smith and Skene, 1997). Although most studies on dissociated DRG neurons involve axotomizing conditioning lesions of peripheral nerves, modest enhancement of neurite outgrowth has also been reported after dorsal rhizotomy, which axotomizes the central axons of DRG neurons (Smith and Skene, 1997). Furthermore, induction of an intrinsic growth state in DRG neurons under physiological conditions does not require axotomy; enhancement of neurite growth has also been demonstrated after voluntary exercise (Molteni et al., 2004), and skin incision induces regeneration-related genes in DRG neurons (Hill et al., 2010). Moderate to severe contusion injury may axotomize a substantial fraction of large-diameter DRG neurons having axons in the dorsal columns, as well as some small-diameter DRG neurons. It also represents a severe regional and systemic stress that might affect distant DRG neurons with intact axons. Therefore, we hypothesized that SCI, like peripheral nerve and cutaneous injury, and voluntary exercise, can enhance the intrinsic growth state of DRG neurons close to and far from the injury site. Here we show that SCI 3 days before dissociation promotes the subsequent elongating growth of neurites in small and medium-sized DRG neurons, but not large DRG neurons.

Methods

Spinal cord injury

Adult Sprague-Dawley rats (225–250 g; Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) were housed with ad libitum access to water and food. All experiments were IACUC approved and in compliance with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Spinal contusion injuries (SCI group) were produced using an Infinite Horizon Impactor. The rats were deeply anesthetized by IP administration of ketamine, xylazine, and acepromazine (Grill et al., 1997). The spinal column was exposed and a laminectomy performed, revealing the dorsal surface of the cord at thoracic level 10. The spinal column was stabilized immediately rostral and caudal to the laminectomy site using modified Adson forceps. The impactor tip was positioned approximately 4 mm above the spinal surface. Impact occurred with 1500 dynes of force delivered over a 1-sec dwell time. Overlying musculature was then sutured with 4.0 Lycryl and the skin closed using sterile, stainless-steel wound clips. Animals in the sham-surgery group received identical surgery, but no contusion. Postoperatively all SCI and sham rats received twice-daily injections of the antibiotic Baytril (for 2 days for the 3 day group, and 5 days for the 1-month animals). Animals in the naïve group received no surgery or drugs.

Dissociation and cell culture

DRGs were dissociated 3 days and 1 month following spinal contusion surgery or sham surgery. Subjects were deeply anesthetized using Beuthanasia, transcardially perfused, and exsanguinated with ice-cold PBS. The spinal column with DRGs attached was excised and immersed in ice-cold PBS. Left and right side DRGs were harvested immediately rostral and caudal to the site of contusion, which was at or very close to T10. DRGs with dorsal root entry zones rostral to the contusion (usually T9 but sometimes T10) are defined as immediately above (“thoracic above”) the site of injury, and those with entry zones caudal to the injury site (usually T11 but sometimes T10) are defined as immediately below the injury (“thoracic below”). Left and right side DRGs were also taken from C5–C7 (“cervical”) and L3–L5 (“lumbar”) levels. DRGs from naïve and sham-treated rats were harvested from the same levels. DRGs were removed, cutting the dorsal roots and spinal nerves 0.5–1.0 cm from the ganglion, and placed in ice-cold DMEM/F12 with 0.1% BSA+1× N1 supplement (Sigma N-6530; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in petri dishes. They were then transferred into DMEM/F12+1× penicillin/streptomycin (1 mL), the sheaths removed, and the rootlets cut off. The ganglia were cut into small pieces in DMEM/F12+1× NI+collagenase (1000 units/mL; Sigma C-9697; total volume 1 mL/2 ganglia), and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 30 min. DRGs were then triturated using a 1000-mL pipette tip. DNAse (10 mg/mL in PBS) was added, the DRGs were further triturated, spun down at 1110 rpm for 11 min, the supernatant aspirated, and cells were resuspended in DMEM/F12+1× N1+10% horse serum+10 mM cytosine arabinoside (500 mL/2 ganglia). The resuspended cells were passed through a 70-μm filter and then plated at low density on 12-mm cover-slips or 5×7 mm well (8 wells/glass slide) coated with poly-L-lysine (50 mg/mL; Sigma P-6282) and laminin (5–10 mg/mL in PBS, Upstate 08–125).

Morphological analysis

Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde 24 h after dissociation. Phase contrast and fluorescence microscopy were used to image the neurons. NIH Image J software was utilized to measure the length of the longest neurite, length of the longest unbranched segment on the longest neurite, number of branches on the longest neurite, and cell body diameter (along the longest axis). Approximately the same numbers of neurons were plated per dish in each group, and low-density cultures were used to minimize overlap of neurites from different neurons. Neurons exhibiting obvious overlap of their neurites with neurites from other neurons were excluded from analysis. The longest neurite was measured from the soma to its most distal tip (see Fig. 1). In some cases several measurements were made to determine which neurite was longest, but only the longest one was used for analysis. Once the longest neurite was identified, we counted the number of branches on the longest neurite. We also measured the longest unbranched segment on the longest neurite to provide an objective measure of neurite elongation that could not be affected by possible unconscious bias in the measurement of the entire length of the longest neurite (which sometimes involves ambiguities, such as the assignment of distal to proximal segments when two long neurites from the same cell intersect, either crossing over or possibly anastomosing). In the 3-day experiments all neuronal measurements were made by an investigator blind to the treatment (i.e., naive, sham, or SCI). Neurons were classified by soma diameter as small (≤30 μm), medium-sized (31–45 μm) or large (>45 μm). For each experiment a minimum of one cover-slip or well was used for neurons sampled from each spinal level. The total number of cells was counted. Growing neurons were defined as cells having at least one neurite longer than the soma diameter. For the 3-day group, photomicrographs were captured at 10× using a Hamamatsu CCD camera (C-2400) on a Leica DMIRB microscope and Zeiss Axio Cam MRm on a Zeiss Axiovert 200M microscope. For the 1-month group a Nikon A1R Confocal Microscope System was used to obtain single-plane images.

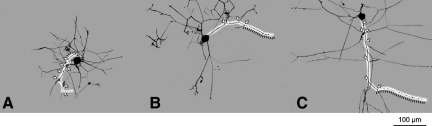

FIG. 1.

Examples of neurite growth in small dorsal root ganglia (DRG) neurons dissociated from rats that were naïve (A), that had received sham surgery (B), or that had received spinal cord injury (SCI) 3 days before dissociation (C). In each case a digital image was taken of a fixed DRG neuron from spinal level T11 to produce a camera-lucida representation of all visible branches. The longest neurite in the neuron sampled from the SCI animal is indicated (white highlight), along with each branch point on the neurite (arrowheads), and the longest unbranched segment on the longest neurite (adjacent dashed black line; scale bar=100 μm).

A subset of cultures in the 3-day and 1-month groups was immunolabeled with antibodies against class III β-tubulin (Sigma #T8660, 1:750), a general marker of neuronal phenotype and against CGRP (Immunostar #24112, 1:3000). Excitation laser lines were 488 nm (for green) and 561 nm (for red) with acquisition in sequential mode, with the appropriate emission filters at 10× and 20×. The software used for data acquisition was NIS-Elements C 3.0. To determine if CGRP was present in the neurites, neurons were scored as 0 if there was either no CGRP staining in the axons or only isolated puncta, and as 1 if continuous staining was present throughout the neurites (“extensive neuritic staining”). This measure is equivalent to the incidence of neurons having extensive neuritic CGRP staining.

Immunocytochemistry

Standard fluorescence immunostaining procedures were used. Cell cultures were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, washed 3 times with Tris-buffered saline (TBS; 10 min) on a shaker, and then blocked for 1 h with 5% serum+0.25% Triton in TBS on the shaker. They were then incubated with primary antibody in 0.25% Triton in TBS (see above for concentrations) overnight (4°C on the shaker) and washed 3 times (10 min) with TBS on the shaker. Secondary antibodies were used at a concentration of 1:500 in 0.25% Triton in TBS (CGRP, 488, A11034; class III betal tubulin, 568, A11004, both from Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA). For the 1-month group we only used class III betal tubulin. They were incubated for 3 h covered with foil. The cells were then washed 3 times (10 min) on the shaker with TBS, mounted, and cover-slipped with Fluoromount-G (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, AL).

Statistical analysis

Morphological parameters were analyzed using Image J (NIH) software, and statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.1. Continuous dependent variables met the assumption of normal distribution and were analyzed with single-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) partitioned by time post-injury, followed by post-hoc Bonferroni-corrected t-tests for between-treatment group comparisons. Proportionate data were compared using Fisher's exact tests. Critical corrected values of alpha were p<0.05.

Results

SCI enhances neurite elongation 3 days after injury

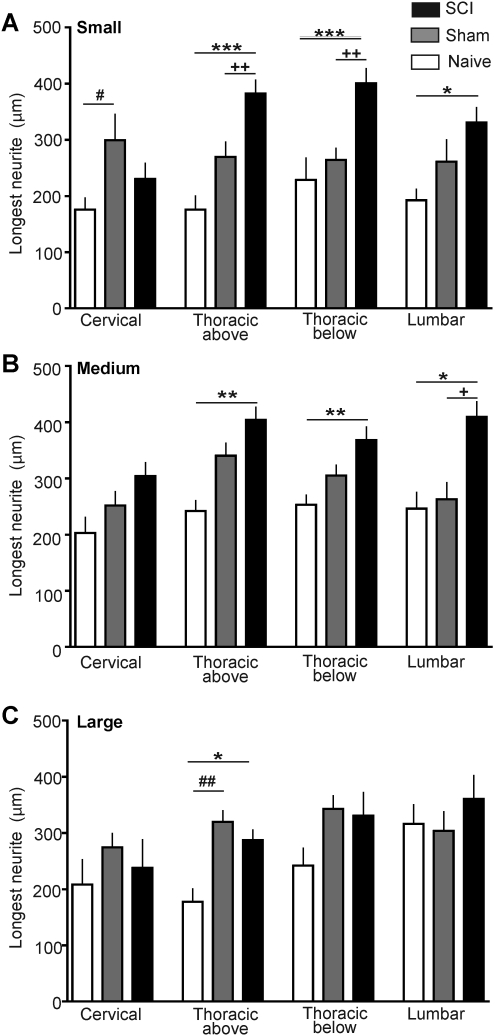

The most extensively documented conditioning effect on subsequently dissociated DRG neurons is elongation of neurites (see Discussion). Measurements on neurons dissociated 3 days after injury revealed increases in maximal neurite lengths following SCI compared to neurons from sham-treated and naïve animals (Fig. 1). Significantly longer neurites were found in small and medium-sized DRG neurons, but not large DRG neurons, taken from all spinal levels sampled except the cervical level (Fig. 2A and B). Significant differences among SCI, sham, and naïve groups were found in small neurons (soma diameter≤30 μm) taken from the following DRGs: lumbar (F(2,30)=3.65, p=0.038), thoracic below the injury (F(2,81)=10.46, p<0.001), and thoracic above the injury (F(2,73)=11.39, p<0.001). Neurons in the SCI group had significantly longer neurites than did small neurons in the naive and sham groups dissociated from DRG immediately above the T10 contusion and immediately below the contusion, and had significantly longer neurites than neurons in the naïve (but not sham) group taken from the lumbar region (p values for individual comparisons are indicated in Fig. 2A). Similarly, significant differences among SCI, sham, and naïve groups were found in medium-sized neurons (31–45 μm soma) taken from the following levels: lumbar (F(2,57)=5.59, p=0.0061), thoracic below the injury (F(2,126)=5.03, p=0.0079), and thoracic above the injury (F(2,132)=5.79, p=0.0039). Individual comparisons showed that medium-sized DRG neurons from the SCI group had significantly longer neurites than neurons from the naïve and sham groups dissociated from both of the sampled thoracic levels as well as the lumbar level (Fig. 2B). In addition, medium-sized neurons in the SCI group had significantly longer neurites than neurons in the sham group at each of these levels (Fig. 2B). No significant effects of SCI were found in neurons from cervical levels, although an overall effect was found in small neurons (F(2,38)=3.52, p=0.0395), with neurons from sham-treated animals having longer neurites than neurons from naïve animals (Fig. 2A). In contrast to the small and medium-sized neurons, large DRG neurons (>46 μm soma) in the SCI group only had significantly longer neurites at one level: immediately above the contusion (F(2,54)=5.30, p=0.0079), and this was only in comparison to the naïve group (Fig. 2C). Sham treatment had considerably less effect on neurite length than did SCI treatment, with the above-mentioned effect in small DRG neurons (Fig. 2A), and large neurons in the sham group having longer neurites than those taken immediately above the injury level in the naïve group (Fig. 2C). Thus, SCI 3 days prior to dissociation promotes elongation of neurites in small and medium-sized neurons dissociated from DRG at spinal levels immediately above and below the thoracic injury site, and in the lumbar region. These differences in neurite length are unlikely to be effects of cell density because the density of DRG neurons measured 1 day after dissociation in the SCI group (91±27 cells/cover-slip) was not significantly different from that of the sham (129±21 cells/cover-slip) or naive (61±21 cells/cover-slip) groups. Large differences in the densities of different cell sizes were not found. Of the 822 cells measured (i.e., the cells that lacked neurite overlap with other neurons), 29% were small, 48% were medium-sized, and 23% were large.

FIG. 2.

Spinal cord injury (SCI) increases the length of neurites growing from dorsal root ganglia (DRG) neurons taken from segments immediately above and below the injury, and from the lumbar region 3 days after T10 contusion injury. (A) Mean length of longest neurite in small neurons (soma diameter < 30 μm) 1 day after dissociation. Sample sizes (number of cells/number of rats) were, respectively, for the naive, sham-treated, and SCI groups at each spinal level: cervical (14/5, 13/6, 14/7), above the injury (11/4, 25/7, 41/8), below the injury (8/3, 40/6, 36/6), and lumbar (9/5, 14/5, 10/5) levels. (B) Mean length of the longest neurite in medium-sized neurons (31–45 μm). Sample sizes were, respectively, for the naive, sham-treated, and SCI groups: cervical (9/5, 31/7, 31/7), above the injury (13/5, 50/7, 71/7), below the injury (20/5, 61/7, 49/7), and lumbar (10/3, 18/6, 32/7) levels. (C) Mean length of the longest neurite in large neurons (>45 μm). Sample sizes were, respectively, for the naive, sham-treated, and SCI groups: cervical (7/2, 18/5, 7/3), above the injury (6/3, 32/5, 19/6), below the injury (13/5, 31/6, 19/4), and lumbar (4/5, 21/6 15/5) levels. Sample sizes are the same for the other morphological parameters measured 3 days after injury (Figs. 3 and 4). In this and subsequent figures error bars denote standard error of the mean, and significant differences between the SCI and naïve groups are indicated by asterisks (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001), while plus signs indicate the corresponding significant differences between the SCI and sham groups (+, ++, +++), and pound signs indicate the differences between the sham and naïve groups (#, ##, ###). (Open bars, naïve group; gray bars, sham group; black bars, SCI group.)

Promotion of neurite elongation occurs without an increase in branching

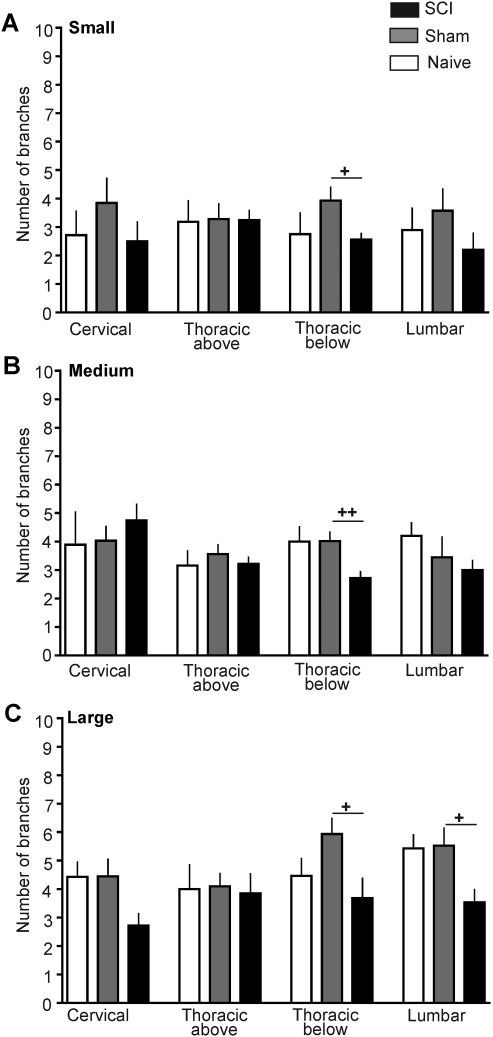

Peripheral conditioning lesions, exercise, and other manipulations have been shown to alter branching frequency of neurites in dissociated DRG neurons (see Discussion). To compare branching characteristics in DRG neurons dissociated from the SCI, sham, and naïve groups, we counted the number of branches and measured the length of the longest unbranched segment on the longest neurite in each dissociated DRG neuron. A few significant differences were found among the SCI, sham, and naïve groups 3 days after injury (Fig. 3); small neurons from thoracic below the injury (F(2,81)=3.37, p=0.0393), medium-sized neurons from thoracic below the injury DRG (F(2,126)=5.25, p=0.0065), and large neurons from lumbar DRG (F(2,40)=3.49, p=0.04). However, neurons dissociated 3 days after SCI showed no statistically significant increases in branch number compared to neurons from any spinal level in the sham and naïve groups in any neuronal size range (Fig. 3). The only notable effect on branching was a significant decrease in branch number immediately below the contusion level in small, medium-sized, and large neurons (Fig. 3), compared to the sham group, and in one case (medium-sized cells, Fig. 3B) for the naïve group. In addition, branch numbers in large neurons taken from the SCI group in lumbar DRG were lower than in neurons from the sham lumbar group (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 3.

Spinal cord injury (SCI) does not increase the number of branches per longest neurite 3 days after T10 contusion injury. (A) Mean number of branches on the longest neurite in small neurons (soma diameter <30 μm) at each level sampled 1 day after dissociation. (B) Mean number of branches in medium-sized neurons (31–45 μm). (C) Mean number of branches on the longest neurite in large neurons (>45 μm). (Open bars, naïve group; gray bars, sham group; black bars, SCI group.)

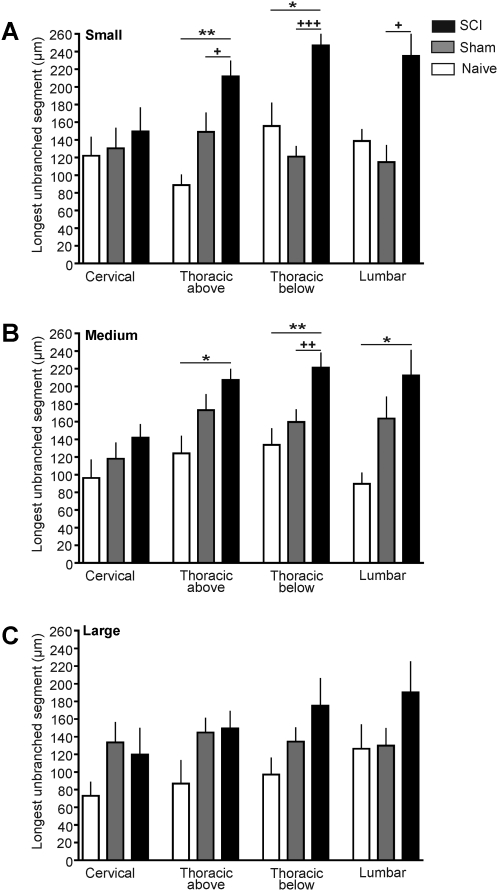

If SCI fails to increase branching frequency while causing neurite elongation, then the longest unbranched segment within the longest neurite should also display elongation following SCI. This prediction was of additional interest because measurement of the longest unbranched (and uncrossed) segment provided an independent index of elongation and branching frequency unconfounded by possible problems distinguishing different neurites (e.g., if neurites cross or neuritic arbors from different neurons overlap, although we excluded cases of obvious overlap). Consistent with predictions from both the elongation data (Fig. 2) and branching data (Fig. 3), SCI had strong effects on the length of the longest unbranched segment 3 days after injury. Significant differences among the SCI, sham, and naïve groups were found in small neurons taken from lumbar DRG (F(2,30)=5.31, p=0.011), thoracic below the injury DRG (F(2,81)=20.70, p<0.001), and thoracic above the injury DRG (F(2,73)=7.61, p=0.001). Neurons in the SCI group had significantly longer unbranched segments than did small neurons in the naive and sham groups dissociated from DRG immediately above the T10 contusion and immediately below the contusion, and lumbar DRG (Fig. 4A). Similarly, significant differences among SCI, sham, and naïve groups were found in medium-sized neurons taken from the following DRG: lumbar (F(2,57)=3.38, p=0.041), thoracic below the injury (F(2,126)=6.17, p=0.0028), and thoracic above the injury (F(2,132)=3.65, p=0.028). Individual comparisons showed that medium-sized DRG neurons from the SCI group had significantly longer unbranched segments than neurons from both the naïve and sham groups dissociated from thoracic below injury DRG, and had longer unbranched segments than the naïve group in neurons from the thoracic below the injury DRG and lumbar DRG (Fig. 4B). No differences were found at the cervical level in small and medium-sized neurons, and no significant differences were found at any level in large DRG neurons (Fig. 4C).

FIG. 4.

Spinal cord injury (SCI) increases the length of the longest unbranched segment in the longest neurite 3 days after T10 contusion injury. (A) Mean length of the longest segment in small neurons (soma diameter <30 μm) 1 day after dissociation. (B) Mean length of the longest segment in medium-sized neurons (31–45 μm). (C) Mean length of the longest segment in large neurons (>45 μm). (Open bars, naïve group; gray bars, sham group; black bars, SCI group.)

Enhanced neurite elongation occurs in CGRP-positive neurons 3 days after SCI

Our finding that SCI enhances elongating growth in small DRG neurons 3 days after injury suggests that SCI may promote an intrinsic growth state in nociceptors, many of which have small diameters (Fang et al., 2005; Gold et al., 1996; Koerber et al., 1988; Lawson, 2002). To obtain additional evidence for enhanced neurite growth in nociceptors following SCI, we immunostained for a marker that has been associated strongly, although not exclusively, with nociceptive function in DRG neurons—CGRP (Hoheisel et al., 1994; Lawson et al., 1996,2002; Tan et al., 2008). We also stained for type III β-tubulin (neurotubulin) in order to visualize neuritic arbors. Soma diameters of neurons positive for CGRP in their somata ranged between 12 and 54 μm, with the median diameter being 30 μm (n=190 neurons). The median soma diameter of lumbar DRG neurons (27 μm) was somewhat less than that of the cervical (29.5 μm) and thoracic neurons (30 and 30.5 μm, above and below the injury, respectively). No significant effects of SCI or sham treatment were found on soma diameter of CGRP-positive neurons. Examples of CGRP-positive neurons dissociated from DRG immediately below the T10 contusion site from each group are shown in Figure 5. Because small and medium-sized neurons had shown significant effects of SCI on elongating growth measures in neurons taken from above-injury, below-injury, and lumbar levels, but not cervical levels (Figs. 2–4), we tested whether CGRP-positive neurons pooled across these same levels (excluding cervical DRG neurons) would show similar effects 3 days after injury (Fig. 6). Significant differences in neurite length among the SCI, sham, and naïve groups were found in CGRP-positive neurons (F(2,198)=8.98, p=0.0002). Individual comparisons showed that neurons in the SCI group had significantly longer maximum neurite lengths than did neurons in the naive and sham groups (Fig. 6A). Significant differences in length of the longest unbranched segment were also found in CGRP-positive neurons among the SCI, sham, and naïve groups (F(2,198)=4.88, p=0.0085). CGRP-positive DRG neurons from the SCI group had significantly longer unbranched segments than neurons from both the naïve and sham groups (Fig. 6B). No significant differences were found in the number of branches of CGRP-positive neurons among groups (F(2,198)=0.20, p=0.81).

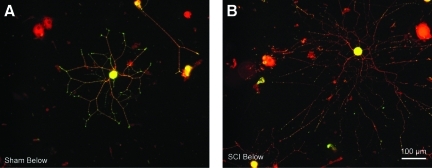

FIG. 5.

Examples of neurite growth in dorsal root ganglia (DRG) neurons immunostained for calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP, green) and neurotubulin (red). Photomicrographs show neurons dissociated from DRG with dorsal root entry zones at spinal level T11 in sham-treated (A) and SCI (B) animals. Notice the longer processes extending from the DRG neuron taken from the SCI rat.

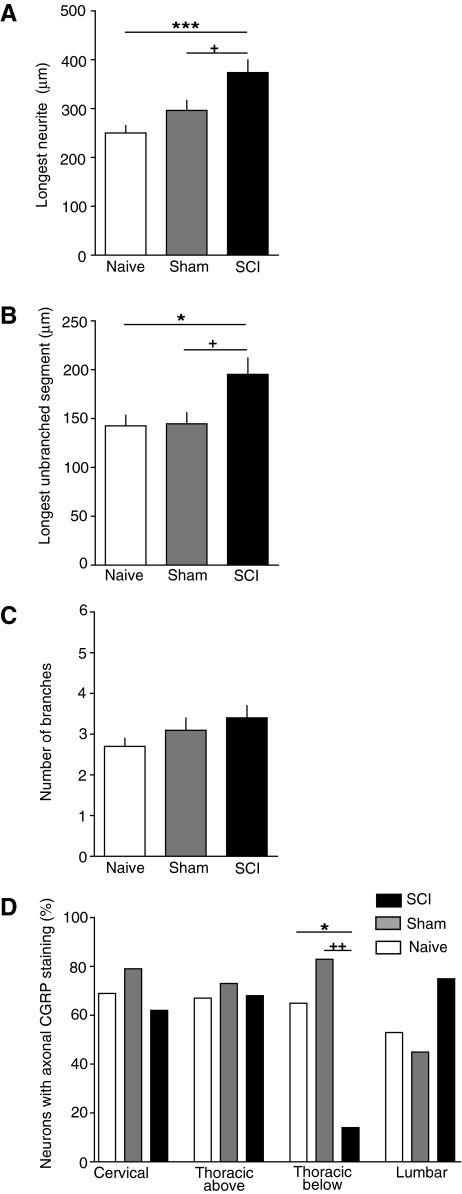

FIG. 6.

Spinal cord injury (SCI) promotes elongating growth of neurites from calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP)-immunoreactive dorsal root ganglia (DRG) neurons from lumbar and thoracic segments. Neurons were fixed 1 day after dissociation, which occurred 3 days after SCI or sham treatment. (A) Increased length of the longest neurite in the SCI group. (B) Increased length of the longest unbranched segment on the longest neurite in the SCI group. (C) Lack of significant effect of SCI on the number of branches on the longest neurite. (D) Decrease in the number of neurons exhibiting uniform neuritic CGRP staining in neurons sampled from DRGs immediately below the thoracic SCI site. A lack of uniform neuritic staining in neurons with CGRP-immunoreactive somata was defined as either the absence of detectable neuritic staining or staining solely in isolated neuritic puncta. Sample sizes (number of cells/number of rats in parts A–D) were, respectively, for the naive, sham-treated, and SCI groups at each spinal level: cervical (15/2, 13/2, 14/2), above the injury (15/2, 13/2, 14/2), below the injury (15/2, 13/1, 14/1), and lumbar (15/2, 13/2, 14/2) levels. (Open bars, naïve group; gray bars, sham group; black bars, SCI group.)

While measuring neurite lengths and branches in CGRP-positive neurons, we noticed an SCI effect on the intensity of CCGP staining in the neurites that was restricted to a single DRG level. In neurons taken from thoracic DRG immediately below the injury site the incidence of neurons having uniform neuritic CGRP staining was significantly lower in the SCI group than in the sham or naive groups (Fig 6D; see also Fig. 5). This suggests that an effect of SCI, perhaps axotomy (see Doughty et al., 1991) of central processes of primary afferents at the site of contusion, combined with other effects of SCI that only occur below the injury level, might cause a reduction in the expression of CGRP and/or its transport into neurites.

SCI produces elongation and early growth of neurites in small DRG neurons 3 days after injury, but has little effect on growth 1 month after injury

An interesting question is whether the intrinsic growth-promoting state observed in vitro 3 days after SCI persists chronically after SCI. To address this question we measured neurites 1 month after injury, focusing on small DRG neurons because (1) they should contain the largest fraction of nociceptors, and (2) they showed robust elongating growth effects 3 days after SCI. Furthermore, because no SCI effects were found in neurons from cervical DRG 3 days after injury (Figs. 2 and 4, and none were apparent in cervical DRG neurons 1 month after injury) we pooled neurons from DRG above and below the injury site and lumbar levels, excluding cervical DRG neurons. In contrast to the effects found 3 days after SCI (Fig. 7A; see also Fig. 2A), no significant differences among the SCI, sham, and naïve groups were found in the length of the longest neurite (F(2,122)=0.01, p=0.99). In addition, no differences were found in the number of branches (F(2,122)=1.66, p=0.19), or longest unbranched segment (F(2,122)=1.04, p=0.35) on the longest neurite 1 month after injury. By these measures, neither SCI nor sham surgery had any effect 1 month after injury.

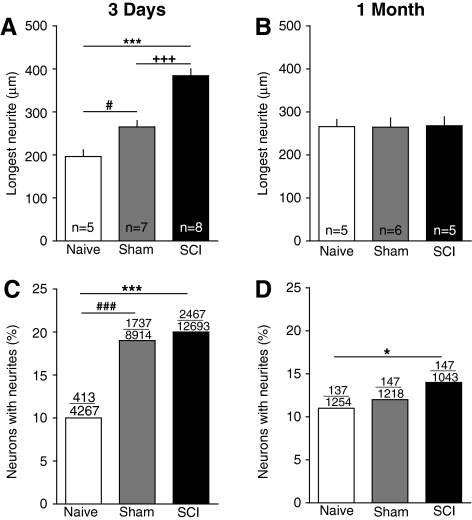

FIG. 7.

Spinal cord injury (SCI) enhances neurite elongation and growth initiation 3 days after injury, but only neurite growth initiation is enhanced 1 month after injury. (A and B) SCI increased the length of the longest neurite on small dorsal root ganglia (DRG) neurons sampled from lumbar and thoracic DRG 3 days after injury, but not 1 month after injury. The 3-day data are pooled from the results shown at each level in Figure 2A (excluding the cervical DRG neurons). Injury also affected the initiation of neurite outgrowth, as monitored by the fraction of neurons having neurite lengths≥the diameter of the cell soma (C and D). Over each bar are shown the number of neurons having neurites over the total number of neurons measured. (C) Neurons dissociated 3 days after injury from both SCI and sham-treated animals were more likely than neurons from naïve animals to have neurites 1 day later. (D) After 1 month, only neurons from SCI animals had a higher incidence of neurites 1 day after dissociation.

Additional information about growth-promoting effects of SCI and sham surgery came from examining the fraction of neurons having neurites longer than the diameter of the soma 24 h after dissociation. Again, we focused on small DRG neurons and pooled results from DRG above and below the injury site, and lumbar levels. The fraction of neurons exhibiting neurites 24 h after dissociation from DRG taken 3 days after injury was significantly greater in both the SCI and sham groups than in the naïve group, while the SCI and sham groups did not differ significantly from each other (Fig. 7C). This suggests that sham surgery by itself accelerates the initiation of neurite outgrowth 3 days after injury. In contrast, 1 month after injury, no significant effects of sham surgery were found on the fraction of neurons bearing neurites, but at this point the SCI group had a significantly greater fraction of neurons bearing neurites than did the naïve group (Fig. 7D). This suggests that SCI, but not sham surgery, has a weak enhancing effect on the initiation of neurite outgrowth 1 month after injury.

Discussion

Properties of the SCI-induced growth-promoting state

We found that SCI promotes elongating growth of neurites without affecting the number of branches on each neurite. Elongation of neurites in cells from SCI animals was not associated with a difference in cell density, and is unlikely to be a consequence of differences in contact among neurites from different neurons because measurements in all groups were restricted to neurons lacking obvious overlap with other neurons' neurites. A similar elongating effect on neuritic growth was described after axotomizing peripheral nerve injury (Lankford et al., 1998; Smith and Skene, 1997), as well as after voluntary exercise (Molteni et al., 2004). These effects, like the effects we find after SCI, were not associated with an increase in neuritic branching or arborization. The lack of a significant effect on branch number allowed us to document the elongation effect, not only by measuring the longest neurite from each neuron (Fig. 2), but also by measuring the longest unbranched segment in each neuron (Fig. 4). Both measures revealed elongation of neurites in small and medium-sized neurons with little effect of SCI on neurite length in large neurons, suggesting that SCI might preferentially modulate the growth state in nociceptors (see below). This contrasts somewhat with the growth-enhancing effect of peripheral axotomy, which promotes neurite elongation in large neurons as well as smaller neurons (Lankford et al., 1998). A potential similarity of the effects of SCI with the growth-promoting effects of peripheral axotomy (Lankford et al., 1998; Smith and Skene, 1997) is an acceleration of the initiation of neurite outgrowth after dissociation by SCI 3 days earlier (Fig. 7C). This measure points to mechanisms distinct from those affecting the neurite length measures because acceleration of neurite growth initiation, unlike neurite elongation, also was produced by sham surgery 3 days after injury. This change in growth initiation could be due to effects of the incision or exposure of the spinal column and laminectomy, which revealed the dorsal surface of the cord at thoracic level 10. Moreover, SCI produced weak acceleration of neurite outgrowth but not elongation 1 month after injury. This suggests that surgical trauma, independent of SCI, transiently promotes neurite growth initiation but has little effect on elongation, while SCI causes a robust, transient promotion of neurite elongation and a longer-lasting, weak potentiation of neurite growth initiation.

An important difference between SCI and peripheral nerve injury models, which pre-axotomize a large fraction of the subsequently dissociated DRG neurons, is that contusion SCI at T10 probably axotomizes relatively few of the affected DRG neurons, especially small and medium-sized neurons in the lumbar region that often project their axons only one or two segments from the dorsal root entry zone (Lidierth, 2007; Traub et al., 1990). Thus, SCI, like voluntary exercise (Molteni et al., 2004), promotes outgrowth of many DRG neurons without the need for conditioning axotomy. This suggests that SCI causes the widespread release of signals that can influence distant DRG neurons (see also Bedi et al., 2010; Carlton et al., 2009; de Groat and Yoshimura, 2010). Two signals that might be released widely and have been associated with signs of increased primary afferent growth within the cord after SCI are nerve growth factor (NGF) (Christensen and Hulsebosch, 1997; Krenz et al., 1999) (although NGF stimulates highly branched, arborizing fiber growth rather than elongating growth; Kalous and Keast, 2010), and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (Song et al., 2008; see also Dougherty et al., 2000; Geremia et al., 2010; Li et al., 2007).

One potential effect of axotomy was seen in neurons sampled from DRG immediately below the contusion site; CGRP staining in the neurites of these cells was significantly reduced (Fig. 7D). Downregulation of CGRP expression occurs in primary afferent neurons following peripheral axotomy (Doughty et al., 1991). A possible downregulation of CGRP in DRG neurons occurring immediately below but not above the injury site 3 days after spinal contusion might reflect an acceleration of the downregulation by interactions of axotomized DRG neurons with effects that occur below the spinal contusion, such as interruption of descending neural influences.

Functional implications of the SCI-induced growth-promoting state

Growth-promoting effects of conditioning lesions are generally assumed to reflect the triggering of a state that normally functions to enhance axonal regeneration and/or compensatory sprouting after peripheral axotomizing injury (Hu-Tsai et al., 1994; Lankford et al., 1998; Smith and Skene, 1997). Our findings suggest that a similar state is triggered in many primary afferents by SCI, where it might promote regeneration of the subset of these sensory neurons that are axotomized by the SCI. However, while a relatively large number of large-diameter, low-threshold primary afferents might be axotomized in dorsal columns at the level of SCI, the large DRG neurons failed to show significant enhancement of intrinsic growth properties (Figs. 2 and 4), suggesting that this state does not aid in the early regeneration of sensory axons in the dorsal columns.

In contrast, the enhanced growth state was prominent in small and medium-sized DRG neurons (Figs. 2 and 4), including neurons that stained for CGRP (Figs. 5 and 6), a marker often found in nociceptors (Hoheisel et al., 1994; Lawson et al., 1996,2002; Tan et al., 2008). This indicates that many of the small and medium-sized neurons displaying elongating growth 3 days after SCI were nociceptors, and therefore that this growth state might affect pain function. Contusive SCI at T10 also promotes widespread spontaneous activity (SA) and hyperexcitability in primary nociceptors (identified by capsaicin sensitivity and isolectin B4 binding) in vitro and in vivo (Bedi et al., 2010). Three days after SCI the growth-promoting state and hyperexcitable-SA state show a similar but not identical distribution in small DRG neurons sampled across different spinal levels: neither state is evident at cervical levels, but both states are expressed immediately below and far below the injury level. However, whereas the growth-promoting state occurs immediately above the injury level 3 days after injury, the hyperexcitable-SA state does not (although it does 1 month or longer after SCI). A major difference between the two states is that the growth-promoting state appears to be transient, largely decaying within 1 month (Fig. 7), whereas the hyperexcitable-SA state shows no sign of declining over many months of testing after SCI (Bedi et al., 2010).

These observations are consistent with SCI producing a relatively transient growth-promoting state in the same nociceptors in which it produces a persistent hyperexcitable-SA state. Because the hyperexcitable-SA state is significantly correlated with chronic allodynia and hyperalgesia after SCI (Bedi et al., 2010), it is interesting to consider the possibility that a relatively transient growth-promoting state also contributes to chronic pain hypersensitivity after SCI. It might do this by promoting the growth of nociceptive fibers into regions where additional synaptic contacts from nociceptors can enhance input to pain pathways. Such growth over the course of days or weeks after SCI might result in persistent new connections that chronically enhance nociceptive transmission into the dorsal horn. Although our results only show that SCI promotes neurite elongation (not branching), it is plausible that this intrinsic growth-promoting state might interact with extrinsic signals in the dorsal horn (signals that would be absent under our in vitro conditions), potentially fostering branching and synapse formation by nociceptors. In this regard, evidence suggests that spinal deafferentation can lead to sprouting of primary afferent branches into deafferented dorsal horn (Carlton et al., 1987; McNeill et al., 1991), which might occur in segments near the injury level after SCI. The possibility of sprouting in the dorsal horn and possible synapse formation after SCI is also supported by reports that SCI increases the density of CGRP-positive fibers in parts of the dorsal horn of rats (Krenz and Weaver, 1998; Krenz et al., 1999; Ondarza et al., 2003; Weaver et al., 2001) and humans (Ackery et al., 2007). Interestingly, Ondarza and associates (2003) found that a measure of active neurite growth, phosphorylated GAP-43, peaked in the dorsal horn close to the same time that we observed enhanced growth in vitro, 3 days post-SCI. However, potential growth effects appear complex. For example, in some of these reports the density of CGRP-positive fibers decreased in some dorsal horn laminae while increasing in others. Furthermore, other studies have described only decreases of CGRP-positive fiber density across most of the dorsal horn after complete spinal transection (Kalous et al., 2007) and spinal compression injury (Kalous et al., 2009). Differences also appear to exist between the growth-promoting effects of central and peripheral injury; a conditioning lesion of the sciatic nerve enhances the intrinsic growth state of some DRG neurons but, in contrast to our findings after SCI, not those expressing CGRP (Kalous and Keast, 2010). Predictions about the consequences of an intrinsic growth-promoting state in nociceptors for growth of fibers in the spinal cord in vivo are not straightforward because of numerous extrinsic controls on axonal growth (e.g., Filbin, 2003; Hoffman, 2010), and the strength of inhibitory controls may vary across different forms of SCI, regions of the cord, and time after injury. Moreover, primary afferents that regenerate or sprout after SCI may be functionally compromised (Tan et al., 2007). Nevertheless, the existence of an intrinsic growth-promoting state in nociceptors and other primary afferent neurons lasting for days and possibly weeks after SCI suggests that growth of these primary afferents, as well as chronic SA and hyperexcitability (Bedi et al., 2010; Carlton et al., 2009; Yoshimura and de Groat, 1997), might contribute to problems such as chronic pain and autonomic dysreflexia. Further investigation of this intrinsic growth-promoting state might also provide information useful for efforts to enhance sensory recovery after SCI.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a fellowship from the Christopher and Dana Reeve Foundation (CDRF) to S.S.B., a grant from the CDRF to E.T.W., NIH grants NS061200 and NS35979 to E.T.W, and NIH grant NS049409 to R.J.G. We thank Bindu Nair for her assistance with surgical procedures and animal care, and Lorenzo Morales for help with graphics.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Ackery A.D. Norenberg M.D. Krassioukov A. Calcitonin gene-related peptide immunoreactivity in chronic human spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2007;45:678–686. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3102020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedi S.S. Yang Q. Crook R.J. Du J. Wu Z. Fishman H.M. Grill R.J. Carlton S.M. Walters E.T. Chronic spontaneous activity generated in the somata of primary nociceptors is associated with pain-related behavior after spinal cord injury. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:14870–14882. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2428-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlton S.M. Du J. Tan H.Y. Nesic O. Hargett G.L. Bopp A.C. Yamani A. Lin Q. Willis W.D. Hulsebosch C.E. Peripheral and central sensitization in remote spinal cord regions contribute to central neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury. Pain. 2009;147:265–276. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlton S.M. McNeill D.L. Chung K. Coggeshall R.E. A light and electron microscopic level analysis of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) in the spinal cord of the primate: an immunohistochemical study. Neurosci Lett. 1987;23:145–150. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(87)90119-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen M.D. Hulsebosch C.E. Spinal cord injury and anti-NGF treatment results in changes in CGRP density and distribution in the dorsal horn in the rat. Exp. Neurol. 1997;147:463–475. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Groat W.C. Yoshimura N. Changes in afferent activity after spinal cord injury. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2010;29:63–76. doi: 10.1002/nau.20761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty K.D. Dreyfus C.F. Black I.B. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglia/macrophages after spinal cord injury. Neurobiol. Dis. 2000;7:574–585. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2000.0318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doughty S.E. Atkinson M.E. Shehab S.A. A quantitative study of neuropeptide immunoreactive cell bodies of primary afferent sensory neurons following rat sciatic nerve peripheral axotomy. Regul. Pept. 1991;35:59–72. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(91)90254-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang X. McMullan S. Lawson S.N. Djouhri L. Electrophysiological differences between nociceptive and non-nociceptive dorsal root ganglion neurones in the rat in vivo. J. Physiol. 2005;565:927–943. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.086199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filbin M.T. Myelin-associated inhibitors of axonal regeneration in the adult mammalian CNS. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2003;4:703–713. doi: 10.1038/nrn1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnerup N.B. Jensen T.S. Spinal cord injury pain—mechanisms and treatment. Eur. J. Neurol. 2004;11:73–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1351-5101.2003.00725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnerup N.B. Johannesen I.L. Sindrup S.H. Bach F.W. Jensen T.S. Pain and dysesthesia in patients with spinal cord injury: A postal survey. Spinal Cord. 2001;39:256–262. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geremia N.M. Pettersson L.M. Hasmatali J.C. Hryciw T. Danielsen N. Schreyer D.J. Verge V.M. Endogenous BDNF regulates induction of intrinsic neuronal growth programs in injured sensory neurons. Exp. Neurol. 2010;223:128–142. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold M.S. Dastmalchi S. Levine J.D. Co-expression of nociceptor properties in dorsal root ganglion neurons from the adult rat in vitro. Neuroscience. 1996;71:265–275. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00433-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill R.J. Blesch A. Tuszynski M.H. Robust growth of chronically injured spinal cord axons induced by grafts of genetically modified NGF-secreting cells. Exp. Neurol. 1997;148:444–452. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hains B.C. Waxman S.G. Sodium channel expression and the molecular pathophysiology of pain after SCI. Prog. Brain Res. 2007;161:195–203. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(06)61013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgren M.E. Goldberger M.E. The recovery of postural reflexes and locomotion following low thoracic hemisection in adult cats involves compensation by undamaged primary afferent pathways. Exp. Neurol. 1993;123:17–34. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1993.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill C.E. Harrison B.J. Rau K.K. Hougland M.T. Bunge M.B. Mendell L.M. Petruska J.C. Skin incision induces expression of axonal regeneration-related genes in adult rat spinal sensory neurons. J. Pain. 2010;11:1066–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman P.N. A conditioning lesion induces changes in gene expression and axonal transport that enhance regeneration by increasing the intrinsic growth state of axons. Exp. Neurol. 2010;223:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoheisel U. Mense S. Scherotzke R. Calcitonin gene-related peptide-immunoreactivity in functionally identified primary afferent neurones in the rat. Anat. Embryol. (Berl.) 1994;189:41–49. doi: 10.1007/BF00193128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu-Tsai M. Winter J. Emson P.C. Woolf C.J. Neurite outgrowth and GAP-43 mRNA expression in cultured adult rat dorsal root ganglion neurons: effects of NGF or prior peripheral axotomy. J. Neurosci. Res. 1994;39:634–645. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490390603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulsebosch C.E. Hains B.C. Crown E.D. Carlton S.M. Mechanisms of chronic central neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury. Brain Res. Rev. 2009;60:202–213. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaken R.J. Joosten E.A. Knuwer M. Miller R. van der Meulen I. Marcus M.A. Deumens R. Synaptic plasticity in the substantia gelatinosa in a model of chronic neuropathic pain. Neurosci. Lett. 2010;469:30–33. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannes C.B. Le T.K. Zhou X. Johnston J.A. Dworkin R.H. The prevalence of chronic pain in United States adults: results of an internet-based survey. J. Pain. 2010;11:1230–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalous A. Keast J.R. Conditioning lesions enhance growth state only in sensory neurons lacking calcitonin gene-related peptide and isolectin B4-binding. Neuroscience. 2010;166:107–121. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalous A. Osborne P.B. Keast J.R. Acute and chronic changes in dorsal horn innervation by primary afferents and descending supraspinal pathways after spinal cord injury. J. Comp. Neurol. 2007;504:238–253. doi: 10.1002/cne.21412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalous A. Osborne P.B. Keast J.R. Spinal cord compression injury in adult rats initiates changes in dorsal horn remodeling that may correlate with development of neuropathic pain. J. Comp. Neurol. 2009;513:668–684. doi: 10.1002/cne.21986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koerber H.R. Druzinsky R.E. Mendell L.M. Properties of somata of spinal dorsal root ganglion cells differ according to peripheral receptor innervated. J. Neurophysiol. 1988;60:1584–1596. doi: 10.1152/jn.1988.60.5.1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krenz N.R. Meakin S.O. Krassioukov A.V. Weaver L.C. Neutralizing intraspinal nerve growth factor blocks autonomic dysreflexia caused by spinal cord injury. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:7405–7414. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07405.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krenz N.R. Weaver L.C. Sprouting of primary afferent fibers after spinal cord transection in the rat. Neuroscience. 1998;85:443–458. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00622-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lankford K.L. Waxman S.G. Kocsis J.D. Mechanisms of enhancement of neurite regeneration in vitro following a conditioning sciatic nerve lesion. J. Comp. Neurol. 1998;391:11–29. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19980202)391:1<11::aid-cne2>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson S.N. Crepps B. Perl E.R. Calcitonin gene-related peptide immunoreactivity and afferent receptive properties of dorsal root ganglion neurones in guinea-pigs. J. Physiol. 2002;540:989–1002. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson S.N. McCarthy P.W. Prabhakar E. Electrophysiological properties of neurones with CGRP-like immunoreactivity in rat dorsal root ganglia. J. Comp. Neurol. 1996;365:355–366. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960212)365:3<355::AID-CNE2>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson S.N. Phenotype and function of somatic primary afferent nociceptive neurones with C-, Adelta- or Aalpha/beta-fibres. Exp. Physiol. 2002;87:239–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lidierth M. Long-range projections of Adelta primary afferents in the Lissauer tract of rat. Neurosci. Lett. 2007;425:126–130. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.L. Zhang W. Zhou X. Wang X.Y. Zhang H.T. Qin D.X. Zhang H. Li Q. Li M. Wang T.H. Temporal changes in the expression of some neurotrophins in spinal cord transected adult rats. Neuropeptides. 2007;41:135–143. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeill D.L. Carlton S.M. Hulsebosch C.E. Intraspinal sprouting of calcitonin gene-related peptide containing primary afferents after deafferentation in the rat. Exp. Neurol. 1991;114:321–329. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(91)90158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molteni R. Zheng J.Q. Ying Z. Gomez-Pinilla F. Twiss J.L. Voluntary exercise increases axonal regeneration from sensory neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:8473–8478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401443101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann S. Woolf C.J. Regeneration of dorsal column fibers into and beyond the lesion site following adult spinal cord injury. Neuron. 1999;23:83–91. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80755-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oblinger M.M. Lasek R.J. A conditioning lesion of the peripheral axons of dorsal root ganglion cells accelerates regeneration of only their peripheral axons. J. Neurosci. 1984;4:1736–1744. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-07-01736.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ondarza A.B. Ye Z. Hulsebosch C.E. Direct evidence of primary afferent sprouting in distant segments following spinal cord injury in the rat: colocalization of GAP-43 and CGRP. Exp. Neurol. 2003;184:373–380. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D.S. Skene J.H. A transcription-dependent switch controls competence of adult neurons for distinct modes of axon growth. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:646–658. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00646.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X.Y. Li F. Zhang F.H. Zhong J.H. Zhou X.F. Peripherally-derived BDNF promotes regeneration of ascending sensory neurons after spinal cord injury. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1707. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan A.M. Petruska J.C. Mendell L.M. Levine J.M. Sensory afferents regenerated into dorsal columns after spinal cord injury remain in a chronic pathophysiological state. Exp. Neurol. 2007;206:257–268. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan L.L. Bornstein J.C. Anderson C.R. Distinct chemical classes of medium-sized transient receptor potential channel vanilloid 1-immunoreactive dorsal root ganglion neurons innervate the adult mouse jejunum and colon. Neuroscience. 2008;156:334–343. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.06.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub R.J. Allen B. Humphrey E. Ruda M.A. Analysis of gene-related peptide-like immunoreactivity in cat dorsal spinal cord and dorsal root ganglia provide evidence for a multisegmental projection of noiciceptive C-fiber primary afferents. J. Comp. Neurol. 1990;302:562–574. doi: 10.1002/cne.903020312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver L.C. Verghese P. Bruce J.C. Fehlings M.G. Krenz N.R. Marsh D.R. Autonomic dysreflexia and primary afferent sprouting after clip-compression injury of the rat spinal cord. J. Neurotrauma. 2001;18:1107–1119. doi: 10.1089/08977150152693782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf C.J. Shortland P. Coggeshall R.E. Peripheral nerve injury triggers central sprouting of myelinated afferents. Nature. 1992;355:75–78. doi: 10.1038/355075a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yezierski R.P. Spinal cord injury pain: spinal and supraspinal mechanisms. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2009;46:95–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura N. de Groat W.C. Plasticity of Na+ channels in afferent neurones innervating rat urinary bladder following spinal cord injury. J. Physiol. 1997;503:269–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.269bh.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]