Abstract

We present direct evidence of an activator-inhibitor system in the generation of the regularly spaced transverse ridges of the palate. We show that new ridges, or rugae, marked by stripes of Sonic hedgehog (Shh) expression, appear at two growth zones where the space between previously laid-down rugae increases. However, inter-rugal growth is not absolutely required: new stripes still appear when growth is inhibited. Furthermore, when a ruga is excised new Shh expression appears, not at the cut edge but as bifurcating stripes branching from the neighbouring Shh stripe, diagnostic of a Turing-type reaction-diffusion mechanism. Genetic and inhibitor experiments identify Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF) and Shh as an activator-inhibitor pair in this system. These findings demonstrate a reaction-diffusion mechanism likely to be widely relevant in vertebrate development.

Regularly spaced structures, from vertebrae to hair follicles to the stripes on a zebrafish, are a fundamental motif in biology. A molecular mechanism by which these might be generated involving a two-component diffusing activator-inhibitor morphogen pair was first proposed by the mathematician Alan Turing1. Experimental demonstrations of this mechanism in vivo are few, and either do not identify both diffusible morphogens or do not exclude alternative mechanisms. In 1952, Turing proposed a simple model showing how the reaction between two chemicals (morphogens) diffusing through a tissue could produce self-regulating periodic biological patterns – the so-called reaction-diffusion model 1,2. Simulations of reaction-diffusion replicate many biological patterns including zebrafish stripes 3, mollusc shells 4, alligator teeth 5, digits of the limb 6 and feather and hair follicle spacing 7,8. However, few systems where reaction-diffusion is implicated are amenable to the experimental perturbation necessary to test fully whether this model explains their behaviour (reviewed in 2,9). In particular, most of the literature relies on simple resemblance of experimental results to computer simulations without identifying the molecular components. In some instances, only one member of the minimal activator-inhibitor pair is identified 3,10. Even where two or more molecular components are identified, alternative mechanisms are not addressed. For example, a clock-and-wavefront model has been implicated in vertebrate somitogenesis 11 while cell contact-meditated lateral inhibition - the inhibition by pattern elements of formation of identical pattern element to establish minimum periodic spacing - regulates the spacing of microchaetae and bristles in Drosophila 12. The recent finding that contact-mediated lateral inhibition can apply even where the spacing is quite sparse 13 suggests that alternative mechanisms could apply in periodic patterns more commonly than previously thought. Crucially, the role of reaction-diffusion mechanisms in spotted patterns such as those of hair and feather follicles 7,8 many need to be re-evaluated in the light of this lateral inhibition alternative.

Palatal rugae are periodic ridges on the hard palate of mammals involved in sensing and holding food 14. Rugal patterning may be a sensitive indicator of environmentally or genetically caused congenital abnormality 15. The number of rugae varies between species: pigs have twenty-one 16, humans four and mice eight 14. Studies in mouse 17,18 show that rugae, marked initially by Shh expression, appear sequentially during embryonic development. Ruga 8 appears first and subsequent rugae appear in a growth zone just anterior to it, each interposed successively between ruga 8 and its predecessor, although the anteriormost ruga, ruga 1, appears out of order (Fig. 1a,b). The mechanism by which this periodic pattern is generated is unknown. Pantalacci et al. speculated that a reaction-diffusion mechanism is responsible 17, but the regular spacing is also consistent with other mechanisms (see below). Moreover, the out-of-sequence appearance of ruga 1, before rather than after ruga 2, is hitherto unexplained.

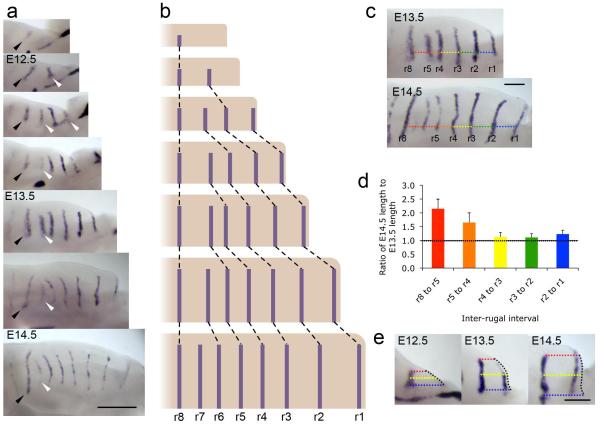

Figure 1. New rugal stripes appear in the palate at regions of growth.

(a) In situ hybridisation for Shh in the developing palatal shelves from E12.0 to E14.5 (anterior right, medial up) illustrating the sequential addition of new rugae (white arrowheads) anterior to r8 (black arrowhead), as described 17,18. Scale bar = 500 μm. (b) Schematic illustrating this sequential addition of rugae with growth. (c) Inter-rugal intervals measured at E13.5 and E14.5, along an axis defined as that of a line from the base of the anterior of the palatal shelf, parallel to the midline of the head. Colours for different interrugal intervals correspond to those used in histogram in panel (d). Scale bar = 200 μm. (d) Ratios of the E14.5 to the E13.5 lengths of the inter-rugal intervals, indicating high levels of growth between r8 and r5, and also elevated growth between r5 and r4, with little growth anterior to r4. Error bars indicate standard deviations. (e) Growth anterior to r2. Coloured dotted lines illustrate the orthogonal distance from r2 Shh expression to the anterior shelf edge (black dotted line) at the base of the shelf, medial edge of the Shh stripe, and midway between (blue, red and yellow respectively). Growth in more medial regions correlates with the appearance of r1 Shh expression at the anterior edge. Scale bar = 200 μm.

To examine whether the addition of rugae is strictly associated with localised anteroposterior growth, we measured inter-rugal spacing at successive days of mid-gestational palates (Fig. 1c). Measurements (Fig. 1d) showed highest growth between ruga 8 and the ruga anterior to it (ruga 5 at the stage shown), exactly where new rugae appear. Some growth between ruga 5 and ruga 4 indicated a growth zone slightly larger than reported 18, although this was insufficient to increase rugal spacing above the approximately 200 μm threshold for new rugal appearance. In contrast, anteroposterior growth in the anterior palate where ruga 1 appears was even lower. Here, however, tissue at a >200 μm distance from ruga 2 was generated by medial growth (Fig. 1e). New Shh expression appeared in this new distal tissue, maintaining the association between growth-associated spacing and stripe appearance and explaining its order.

The coupling of growth with the generation of new stripes is consistent with a simple fixed inhibitory distance, lateral inhibition mechanism (Fig. 2a) in which a stripe generates an inhibitor activity whose local level declines with distance from the stripe: as tissue grows and space between stripes increases, the inhibitor level falls below a threshold and a new stripe can form. (Lateral inhibition in Drosophila takes this general form, although cellular mechanisms involving Notch-Delta signalling and cell-cell contact are not essential to it.) In this model, growth inhibition stops stripe addition. This is consistent with the correlation between the time of growth and the number of rugae among related rodent species 14. We found that culturing palatal explants in vitro maintained mediolateral growth (indicating healthy tissue) but arrested anteroposterior growth (Supplementary Fig. S1). Unexpectedly, despite the lack of anteroposterior growth, new Shh stripes were still added in culture, but at smaller intervals than in vivo (Fig. 2b, c). This pattern scaling shows that growth and stripe generation are not rigidly coupled.

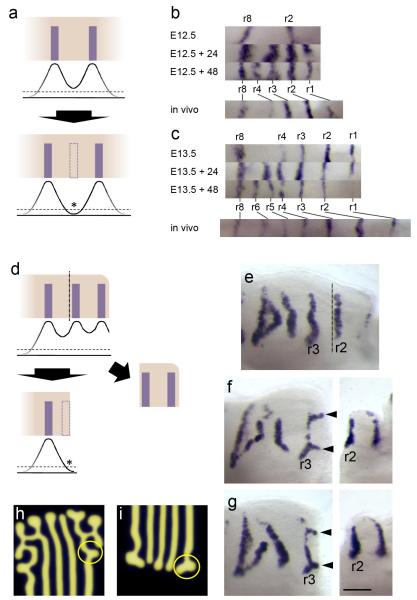

Figure 2. Rugal stripe patterning size-scales with growth inhibition and branches when an established stripe is excised.

(a) Schematic of a lateral inhibition hypothesis for rugal spacing. Curves represent levels of inhibitor produced by rugae and dashed line represents inhibitory threshold. Growth between rugae would allow the level of inhibition to fall below threshold (asterisk) allowing the formation of a new ruga (dashed rectangle). (b,c) Rugal Shh stripes of palatal shelves of littermates cultured for 0, 24 and 48 hours explanted at (b) E12.5 and (c) E13.5 demonstrating the addition of rugae without AP growth at closer spacing than the equivalent stripes in vivo. (d) Schematic representing the predicted effect of removing a ruga under a lateral inhibition model. Removing the anterior of the palatal shelf by cutting posterior to the second ruga (vertical dashed line), removes inhibition from second ruga allowing inhibition to fall below threshold level at the cut edge (asterisk) leading to the formation of a new ruga (dashed rectangle). (e,f,g) Experimental result differs dramatically from the prediction: posterior palatal shelves cut adjacent to ruga 2 and cultured for 48 hours (two examples, f and g, with immediately fixed anterior, uncultured anterior pieces to the right) analysed by Shh in situ hybridisation show branches to ruga 3 at curves in the ruga (black arrowheads), not seen in uncut controls (e). (Dashed line in (e) represents where cut is in cut shelves.) (h, i) Branches to stripes are readily replicated in reaction-diffusion simulations generated using Turing equations as in ref 2 – compare pattern in circles in h and i with those at arrowheads in f, g. All specimens oriented with anterior to right, medial up.

Pattern scaling (rather than truncation) also argues against a lateral inhibition mechanism of the type described above, although if our method of growth inhibition somehow also causes reduced stripe inhibition, this model is not ruled out. We therefore tested a stronger prediction of this model, namely that removal of a stripe should lead to regeneration of a stripe near the cut edge, since inhibition is also removed there (Fig. 2d). Embryonic day (E) 13.5 palatal explants were cut immediately posterior to the second ruga (Fig. 2e). The anterior shelf was stained for Shh expression to confirm that the desired ruga was cleanly removed. When the posterior shelf was cultured for 48 hours, new domains of Shh expression appeared anterior to ruga 3 in the form of “branches”, i.e. stripes branching anteriorly to ruga 3, extending towards the cut edge (Fig. 2f, g). Similar patterns were seen with cuts posterior to ruga 3 (not shown). This demonstrates that the pattern is labile and that a lateral inhibition mechanism of the type described above does not apply because new expression contiguous with existing expression is forbidden. Such expression can be explained if a self-propogating, diffusing activator is introduced. This is a definitive and distinguishing feature of Turing-type reaction-diffusion mechanisms. The branches emerged from slight convexities of the pre-existing stripe, producing junctions of expression lines at 120° angles (Fig. 2f, g), a typical manifestation of Turing-type reaction-diffusion patterning mechanisms (Fig. 2h, i). Branching or labyrinthine patterns are at the transition between stripes and spots achieved, for example, by reducing the basal levels of both activator and inhibitor 3. Branches are inhibited by existing stripes, but grow where neighbouring stripes are absent (Fig. 2h, i and Supplementary Fig. S2).

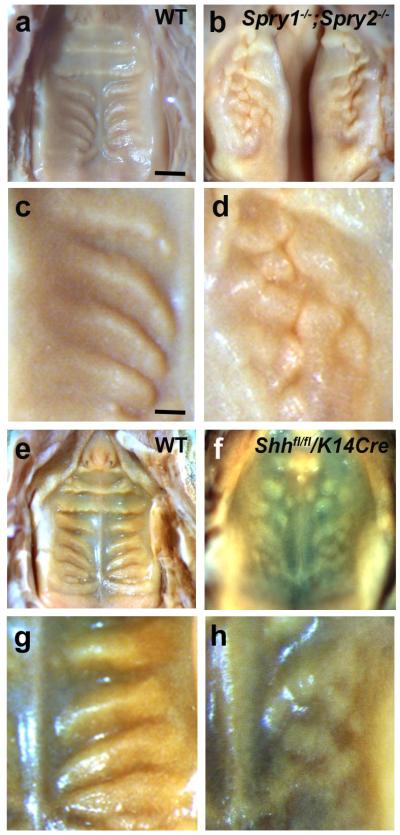

Turing systems are defined by diffusible activator and inhibitor morphogens. Loss of Fgfr2 or Fgf10 genes results in a lack of palatal rugae 19,20 suggesting FGF as an activator in this system. To address this possibility, we examined mice lacking two intracellular antagonists of FGF signalling, Sprouty (Spry) 1 and Spry2 (i.e. compound mutant mice Spry1−/−;Spry2−/− (ref. 21)) as FGF signalling gain-of-function mutants. Spry1 and Spry2 are also FGF response markers and are expressed in palatal rugae during development (ref. 22, Supplementary Fig. S3 and data not shown). Spry1−/−;Spry2−/− mice showed highly disorganized palatal rugae including broader and ectopic ruga formation (Fig. 3a-d). Broader and disorganised rugae were prefigured by broader and disorganised Ptch1 expression associated with epithelial thickening at earlier stages (Supplementary Fig. S4). Palates from these mutants bore many tightly packed bumps rather than well-spaced ridges, suggesting more widespread as well as disorganised rugal tissue.

Figure 3. Sprouty and Shh loss-of-function mutants implicate FGF and Hedgehog signallng in rugal patterning.

Palates of P0 mice viewed from the oral side, anterior up. (a-d) Increased FGF signaling in Spry1−/−;Spry2−/− mutant mice results in disorganized and compacted rugae (b, detail in d) compared to wildtype (a, detail in c). Rugal phenotype can be distinguished despite cleft palate in these mutants. (e-h) Down-regulation of Shh in K14-Cre/Shhfl/fl mice results in a similar phenotype of disorganized, compacted rugae (f, detail in h) compared to wildtype controls (e, detail in g). Scale bar in panel a = 1 mm (for a, b, e, f); scale bar in panel c = 0.3 mm (for c, d, g, h).

The rugal stripe marker Shh is itself a well-known morphogen and the expression of its canonical target genes Patched (Ptch1) and Gli1 in and around the rugae show that it is actively signalling there (Supplementary Fig. S3) and prefigures the epithelial thickening of the rugae, even in the Spry1−/− ;Spry2−/− palates (Supplementary Fig. S4). To address Shh’s role in rugal patterning, we investigated the effects of Shh loss-of-function by examining mice with a conditional deletion of Shh in oral epithelial cells (K14-Cre/Shhfl/fl; ref. 23). These mutants had highly disorganized rugae including ectopic ruga formation (Fig. 3e-h). Disorganised rugae were prefigured by a similarly disorganised pattern of FGF signalling, as shown by in situ hybridisation for Spry2 expression coincident with thickened epithelium at E14.5 (Supplementary Fig S4). The similarity of the K14-Cre/Shhfl/fl phenotype to that of the Spry double null mutant suggests that Shh acts like Spry, that is as an inhibitor of FGF signalling and of rugae in this system. Suggestively, in both mutant phenotypes the patterns become fragmented, suggesting that this system is close to a stripe-spot transition well-modelled by Turing equations 24. However, despite the occurrence of Cre reporter activity in both the rugal placodes and the thin inter-rugal epithelium of K14-Cre/ROSA26-lacz embryos (Supplementary Fig. S5), one cannot absolutely rule out the existence of a subset of cells that escaped or had delayed recombination events that could contribute to the uneven patterning. Thus, more direct tests of the signaling pathway function were needed.

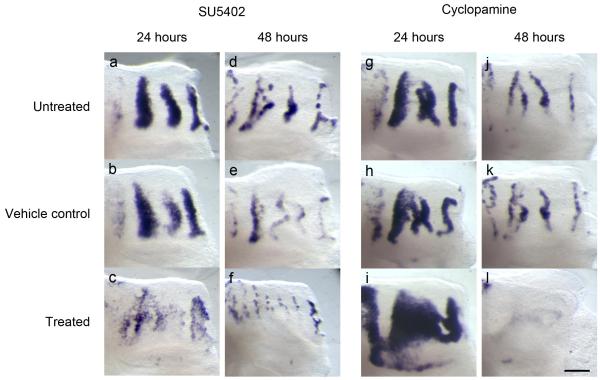

To analyze the roles of FGF and Shh more directly, we applied chemical inhibitors of these signals to explants in culture. Palatal explants were cultured with the FGF inhibitor SU5402, the Shh signalling inhibitor cyclopamine or the Shh agonist purmorphamine. Explants treated with SU5402, cyclopamine and purmorphamine and probed for Spry2 and Ptch1 expression confirmed that FGF and Shh signalling were inhibited or enhanced as expected for these reagents (Supplementary Fig. S6). After 24 and 48 hours, SU5402-treated explants showed substantially reduced levels and dispersed pattern of Shh expression compared to controls (Fig. 4a-f). Culturing similar palatal explants with cyclopamine resulted in a dramatic broadening of Shh expression compared to controls (Fig. 4g-i) at 24 hours. Other markers of rugal patterning, namely Spry2 expression and epithelial thickening were similarly broadened (Supplementary Fig. S7). After 48 hours culture there was almost no detectable Shh expression in treated palates, unlike in controls (figure 4j-l), suggesting a “recoil” effect due to feedback control of expression. Treatment with the Shh-mimic purmorphamine 25 had the effect of inhibiting Shh expression, narrowing and eventually suppressing the stripes (Supplementary Fig. S7), confirming that Shh signalling inhibits rugae. This also demonstrates negative feedback by Shh signalling on its expression. (One might speculate that the abovementioned “recoil” effect is due to such feedback being triggered as rising Shh synthesis after cyclopamine treatment overcomes the inhibition after 24 hours.)

Figure 4. Inhibition of FGF and Hedgehog signaling in palatal explants demonstrate their activatory and inhibitory roles in rugal stripe maintenance respectively.

Pattern of rugae, visualized by Shh in situ hybridization in palatal shelf explants cut posterior to ruga 2 and cultured for 24 (a-c, g-i) and 48 (d-f, i-l) hours. (a-f) Culture with the FGF inhibitor SU5402 shows reduced levels of Shh expression in treated explants (c,f) relative to controls (a,b,d,e). (g-l) Culture with the Hedgehog inhibitor cyclopamine shows increased levels of Shh expression in treated explants after 24 hours (i) relative to controls (g, h). Levels of Shh expression then fall after 48 hours culture with Cyclopamine (l) compared to controls (j,k). All specimens oriented with anterior to right, medial up. Scale bar = 200 μm.

These results indicate that the FGF pathway is activatory, and the Hedgehog pathway inhibitory in a Turing-type reaction-diffusion system for the striped pattern that establishes and maintains the palatal rugae. It is highly unlikely that FGF and Shh are the sole diffusible morphogens in this system. BMP4 is expressed in the rugal mesenchyme and regulates Shh expression in the palate 26 and mutations in Wise/Sostdc1, which interacts with BMP and Wnt morphogens has a rugal phenotype quite similar to those in this work 18 and canonical Wnt signalling has been directly implicated in rugal patterning 27. Moreover, size-scaling also suggests additional components 28. The interaction between these different pathways has the potential to be complex (e.g. 29), but although fuller understanding will require a more quantitative analysis, the work presented here indicates that this beautifully rectilinear system is amenable to experiments that reveal the character of the underlying mechanism. A recent analysis of the patterning of the regularly-spaced cartilage rings in the trachea has implicated FGF10 and Shh signalling 30 (albeit without identifying them as Turing activator and inhibitor). While other components (e.g. other FGFs and Wnt signalling) have yet to be studied in that system, the involvement of these two pathways suggests that regular striped patterns may be similarly generated in multiple contexts in the mammalian body.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Arthur Lander and Michael Cohen for useful advice on models, Gail Martin (UCSF), for the Spry2 mutant mice, Maiko Kawasaki, Yoko Otsuka-Tanaka and Katsushige Kawasaki for assistance with in situs, and Mark Miodownik and Melissa Rubock for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was funded by MRC grant G0801154 to J.B.A.G. and M.T.C.

APPENDIX

Methods

Generation of embryos

Wild type CD1 embryos were harvested, staged and stained by wholemount in situ hybridization using established methods 31,32. Measurement of palates before dissection and after staining confirmed that no significant shrinkage occurred (data not shown). Mutant mice were generated from alleles previously described 23,33,34. Phenotypes were determined for at least three embryos in all cases.

Explant culture

Palatal explants were cultured (37°C, 5% CO2) using the Trowell technique 26 in DMEM (Sigma), 20 U/ml pen-strep (GibcoBRL), 10% FBS (GibcoBRL), 50 mM transferrin (Sigma) and 150 μg/ml ascorbic acid (Sigma). For cutting and inhibitor experiments, serum-free Advanced D-MEM/F12 (GibcoBRL) supplemented as above, was used. Medium was changed after 24 hours for longer cultures. Microdissections used 0.1 mm tungsten needles. SU5402 (Calbiochem) was diluted in medium from 10 mM in DMSO stock; Cyclopamine (Sigma) from 20 mg/ml-ethanol stock. Experiments were repeated at least four times for each condition.

Imaging, measuring and simulations

Explants placed in a minimum volume of PBS in wells cut into 1% agarose were digitally imaged under a stereo dissecting microscope and measurements made using the Ruler in ImageJ (from the NIH ImageJ website) calibrated with a micrometer slide. Dimensions of fixed material were within 8% of those of fresh, unfixed material (data not shown). Simulations of reaction-diffusion patterning were performed using the Javascript in ref 2 with the parameters du=0.03, D u=0.02, a u=0.1, b u=−0.06, c u=0, Fmax=0.2, dv= 0.06, D v=0.5, a v=0.1, b v=+0, c v=−0.2, Gmax=0.5.

Footnotes

Author Information

A.D.E. performed palate measurements and explant experiments; T.P., A.O., P.T.S., M.A.B., A.G.-L. and M.T.C constructed and analyzed the mouse mutants; S.K. did the modeling; A.D.E., M.T.C. and J.B.A.G. designed the explant experiments and wrote the manuscript with contributions from the other authors.

References

- 1.Turing AM. The chemical basis of morphogenesis: A reaction-diffusion model for development. Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. of London, Series B: Biological Sciences. 1952;237:37–72. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kondo S, Miura T. Reaction-diffusion model as a framework for understanding biological pattern formation. Science (New York, N.Y) 329:2010. doi: 10.1126/science.1179047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asai R, Taguchi E, Kume Y, Saito M, Kondo S. Zebrafish leopard gene as a component of the putative reaction-diffusion system. Mech Dev. 1999;89:87–92. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meinhardt H. The Algorithmic Beauty of Seashells. 4th edn Springer-Verlag; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kulesa PM, et al. On a model mechanism for the spatial patterning of teeth primordia in the Alligator. Journal of theoretical biology. 1996;180:287–297. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miura T, Shiota K, Morriss-Kay G, Maini PK. Mixed-mode pattern in Doublefoot mutant mouse limb--Turing reaction-diffusion model on a growing domain during limb development. Journal of theoretical biology. 2006;240:562–573. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2005.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang TX, Jung HS, Widelitz RB, Chuong CM. Self-organization of periodic patterns by dissociated feather mesenchymal cells and the regulation of size, number and spacing of primordia. Development. 1999;126:4997–5009. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.22.4997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sick S, Reinker S, Timmer J, Schlake T. WNT and DKK determine hair follicle spacing through a reaction-diffusion mechanism. Science. 2006;314:1447–1450. doi: 10.1126/science.1130088. New York, N.Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baker RE, Schnell S, Maini PK. Waves and patterning in developmental biology: vertebrate segmentation and feather bud formation as case studies. The International journal of developmental biology. 2009;53:783–794. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072493rb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newman SA, Bhat R. Dynamical patterning modules: a “pattern language” for development and evolution of multicellular form. The International journal of developmental biology. 2009;53:693–705. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072481sn. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldbeter A, Pourquie O. Modeling the segmentation clock as a network of coupled oscillations in the Notch, Wnt and FGF signaling pathways. Journal of theoretical biology. 2008;252:574–585. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Axelrod JD. Delivering the lateral inhibition punchline: it’s all about the timing. Sci Signal. 3:pe38–2010. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.3145pe38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen M, Georgiou M, Stevenson NL, Miodownik M, Baum B. Dynamic filopodia transmit intermittent Delta-Notch signaling to drive pattern refinement during lateral inhibition. Developmental cell. 2010;19:78–89. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pantalacci S, Semon M, Martin A, Chevret P, Laudet V. Heterochronic shifts explain variations in a sequentially developing repeated pattern: palatal ridges of muroid rodents. Evol Dev. 2009;11:422–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2009.00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikemi N, Kawata M, Yasuda M. All-trans-retinoic acid-induced variant patterns of palatal rugae in Crj:SD rat fetuses and their potential as indicators for teratogenicity. Reprod Toxicol. 1995;9:369–377. doi: 10.1016/0890-6238(95)00024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pospieszny N, Janeczek M, Klećkowska J. Morphology Of The Incisive Papilla (Papilla Incisiva) Of Pigs During Different Stages Of Their Prenatal Period. 2003 < http://www.ejpau.media.pl/volume6/issue1/veterinary/art-04.html>.

- 17.Pantalacci S, et al. Patterning of palatal rugae through sequential addition reveals an anterior/posterior boundary in palatal development. BMC Dev Biol. 2008;8:116. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-8-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Welsh IC, O’Brien TP. Signaling integration in the rugae growth zone directs sequential SHH signaling center formation during the rostral outgrowth of the palate. Developmental biology. 2009;336:53–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rice DP, Rice R, Thesleff I. Fgfr mRNA isoforms in craniofacial bone development. Bone. 2003;33:14–27. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(03)00163-7. doi:S8756328203001637 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hosokawa R, et al. Epithelial-specific requirement of FGFR2 signaling during tooth and palate development. J Exp Zool B Mol Dev Evol. 2009;312B:343–350. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.21274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simrick S, Lickert H, Basson MA. Sprouty genes are essential for the normal development of epibranchial ganglia in the mouse embryo. Developmental biology. 2011;358:147–155. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Porntaveetus T, Oommen S, Sharpe PT, Ohazama A. Expression of Fgf signalling pathway related genes during palatal rugae development in the mouse. Gene Expr Patterns. 2010;10:193–198. doi: 10.1016/j.gep.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dassule HR, Lewis P, Bei M, Maas R, McMahon AP. Sonic hedgehog regulates growth and morphogenesis of the tooth. Development. 2000;127:4775–4785. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.22.4775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shoji H, Iwasa Y, Kondo S. Stripes, spots, or reversed spots in two-dimensional Turing systems. Journal of theoretical biology. 2003;224:339–350. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(03)00170-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sinha S, Chen JK. Purmorphamine activates the Hedgehog pathway by targeting Smoothened. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:29–30. doi: 10.1038/nchembio753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Z, et al. Rescue of cleft palate in Msx1-deficient mice by transgenic Bmp4 reveals a network of BMP and Shh signaling in the regulation of mammalian palatogenesis. Development. 2002;129:4135–4146. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.17.4135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin C, et al. The inductive role of Wnt-beta-Catenin signaling in the formation of oral apparatus. Developmental biology. 2011;356:40–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ishihara S, Kaneko K. Turing pattern with proportion preservation. Journal of theoretical biology. 2006;238:683–693. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2005.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahn Y, Sanderson BW, Klein OD, Krumlauf R. Inhibition of Wnt signaling by Wise (Sostdc1) and negative feedback from Shh controls tooth number and patterning. Development. 2010;137:3221–3231. doi: 10.1242/dev.054668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sala FG, et al. FGF10 controls the patterning of the tracheal cartilage rings via Shh. Development. 2011;138:273–282. doi: 10.1242/dev.051680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin P. Tissue patterning in the developing mouse limb. The International journal of developmental biology. 1990;34:323–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mootoosamy RC, Dietrich S. Distinct regulatory cascades for head and trunk myogenesis. Development. 2002;129:573–583. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.3.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Basson MA, et al. Sprouty1 is a critical regulator of GDNF/RET-mediated kidney induction. Developmental cell. 2005;8:229–239. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shim K, Minowada G, Coling DE, Martin GR. Sprouty2, a mouse deafness gene, regulates cell fate decisions in the auditory sensory epithelium by antagonizing FGF signaling. Developmental cell. 2005;8:553–564. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.