Abstract

Healthcare and social needs for mature adults aged 50 years or older differ from those of younger adults due to stigma concerning HIV in older people, beliefs that engagement in sexual activity no longer applies, age driven comorbidities and responses to antiretroviral treatment, which complicate HIV diagnosis and management. In the face of a growing HIV epidemic in mature adults, mostly due to infected people aging with HIV, but also due to new infections in this age group, HIV services, which mostly cater for HIV in young adults and children, and HIV education messages and interventions, which mainly target young adults, leave the mature adult exposed and vulnerable to HIV transmission and to a lack of care and treatment thereafter.

Keywords: ART, diagnosis, elderly, HIV, older adults, prevention

Growing proportion of mature adults

Southern Africa has the continent’s highest percentage of older inhabitants, with South Africa having the highest proportion [101], owing to economic development and healthcare improvements. In 2006, 14.6% of the South African mid-year population were aged 50 years or older (mature adults), rising to 14.9% in 2010. The rise in absolute numbers of people aged over 50 years, from 6.93 million in 2006 to 7.47 million in 2010, exceeded the growth of the total population [102,103]. Despite the over 50s constituting a significant proportion of the population, there is a lack of relevant, reliable data at national and local levels on the health of older people and the associated health and social benefits and problems in sub-Saharan Africa (sSA) [1,101,104]. Consequently, this negatively impacts on strategic healthcare planning for this age group. In this article, we discuss the epidemiology of HIV among older adults, with a special focus on sSA, including the use of data from a cohort in a rural area in northern KwaZulu Natal in South Africa. We discuss specific and practical issues in older patients, including how and why older people are at risk, the burden of HIV on mature adults, special needs of mature adults due to age-related issues such as decreased physiological function and old age morbidities and the lack of age-relevant HIV-friendly services, as well as possible intervention strategies. We also highlight the critical gap in knowledge on HIV in mature adults that, if not addressed, may hinder UNAIDS’s vision of zero discrimination, zero new HIV infections and zero AIDS-related deaths through universal access to effective HIV prevention, treatment, care and support [105], and we emphasize the urgent need to focus on mature adults in the face of an aging HIV-infected cohort.

Burden of HIV in mature adults

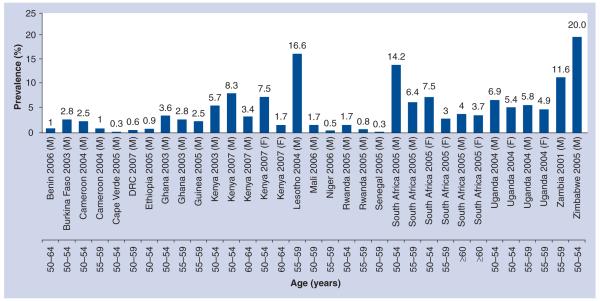

Worldwide, and particularly in sSA, the HIV epidemic substantially affects older people, not only through their role as caretakers of their adult HIV-infected children and orphaned grandchildren, but also as they themselves are increasingly infected with HIV [2,3,106]. According to the WHO, although in 2005 approximately 2.8 million adults aged 50 years or older were living with HIV worldwide [4], older people are largely neglected in the targeting of the HIV response [2,3,5,6,104]. Reporting mechanisms and estimates of epidemiological trends usually only encompass adults of reproductive ages (15–49 years) through antenatal screening and demographic health surveys [3,7,8,107]. At an international level, UNAIDS and other agencies that report on the state of the epidemic [3,7,102,103] have limited or no data on the number of HIV-infected mature adults (50 years or older) in developing countries, which face the largest burden of HIV. Only a few countries have comprehensive empirical data on HIV prevalence in mature adults; a review of all surveys conducted after 2000 in sSA gave 43 demographic health surveys, of which 39 included people aged ≥50 years, but only if they were men, and the upper age limits ranged from 54 to 64 years. Of these 39 surveys, only 18 provided data on the prevalence of HIV infection using population-based HIV testing [8]. The true HIV burden in mature adults thus remains largely unknown and unappreciated in most sSA countries, including South Africa [3,8]. Furthermore, the available reports do not have a consistent cut-off age, with most only going up to 59 years of age and being predominantly male based [3,9], leading to difficulties in comparisons across settings, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. National HIV prevalence estimates in adults aged 50 years or older in sub-Saharan Africa.

DRC: Democratic Republic of Congo; F: Female; M: Male.

Adapted from [8].

Although in 2006 UNAIDS started to report the numbers of HIV-positive people aged >49 years, the data are brief and limited to this statement: “around 2.8 million adults aged 50 years and above were living with HIV in 2005” [8,107]. In sSA, research and reports on the impact of the HIV epidemic on older people has primarily focused on the role of grandparents as caretakers of orphans [8,10], with the focus in recent years shifting slightly with the realization that HIV also affects mature adults. A report that extrapolated prevalence from UNAIDS HIV prevalence rates in 2008 (using HIV prevalence rates from the Demographic Health Survey [DHS] relating to people aged 15–49 years and national population structures) estimated that, in 2007, sSA had 3 million mature adults living with HIV, translating to 14.3% of all sSA HIV-positive people. Mozambique, Nigeria, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe had the highest HIV prevalence, accounting for 54% of all mature adult HIV infections [8].

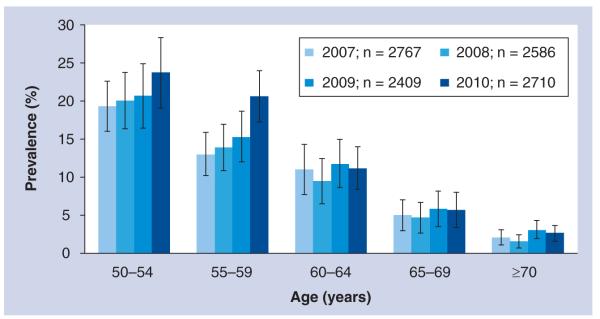

A national survey in 2008 in South Africa reported HIV prevalence rates as high as 10.4 and 10.2% in 50–54-year-olds, 6.2 and 7.7% in 55–59-year-olds and 3.5 and 1.8% in ≥60 year-old males and females, respectively [108]. A more recent publication using population-based surveillance data (n = 2791) in rural South Africa estimated the overall HIV prevalence rate in adults aged 50 years or older at 9.5%, with peak prevalences of 29.5% in males aged 50–54 years and 17.3% in females aged 50–54 years [2]. Lower prevalences have been reported in rural Cameroon (2.6% in men and women aged 55–70 years) and Ethiopia (5%), while Tanzania reports a higher prevalence of 15% [2,8,9]. In Kenya, estimated HIV prevalence in those aged 50–54 years was 8%, which is twice as high as the prevalence in 15–24-year-olds [9]. In Kenya, the only African country with two fully nationally representative DHS datasets for older adults (2003 and 2008/2009), there is evidence of increased prevalence from 5.7 to 8.3% in 50–54-year-old males [11]; for females, there were no trend data available. In a recent analysis using population-based data from rural South Africa collected from 2007 to 2010, increasing prevalence across all age groups over 50 years was observed (Figure 2), and this was evident in both sexes.

Figure 2.

HIV prevalence rates in adults aged 50 years or older over a 4-year period in rural South Africa

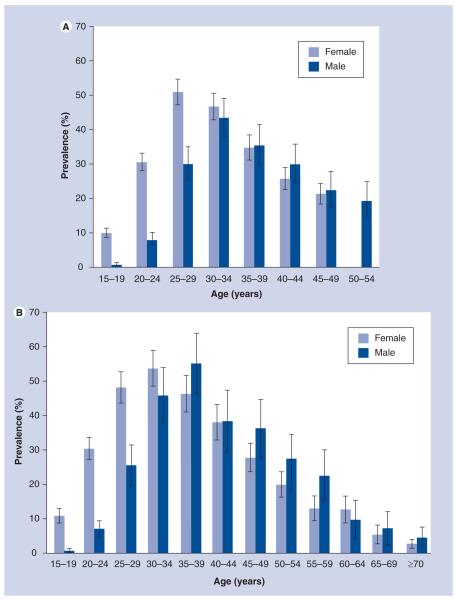

Although the prevalence estimates reported in this article in terms of the proportion of older people infected with HIV expressed as a percentage of the total HIV-infected cohort may seem low, absolute numbers affected are considerable, bearing in mind that sSA accounts for 67% of all people living with HIV globally, with 5.24 million approximated to be living in South Africa in 2010 [103,107]. The proportion of mature adults living with HIV is expected to grow due to increased life expectancy as AIDS-related mortality rates declining both at individual and population levels due to antiretroviral therapy (ART), and survival is now expected to exceed 15–20 years from sero-conversion [12,13], late diagnosis of patients who remain un aware of their status for a long time [14–16] and an increase in the number of people infected with HIV in later stages of life [3]. Although the evidence of this is still to be fully realized in developing countries where ART was only introduced recently, evidence from rural South Africa is already showing a trend toward an aging HIV cohort; in 2004, the HIV prevalence peaked in women aged 25–29 years and men aged 30–34 years [17]. However, in 2009 in this same population, prevalence peaks for both sexes had shifted forward 5 years, with the 2009 peak being much broader, likely depicting that people infected in earlier years are living longer owing to increased uptake of ART, in addition to new infections occurring in older age groups or possibly late diagnosis of people infected in early life (Figure 3A & 3B). If this current scenario remains constant, within the next decade, peak prevalence will be in those aged 50 years or older.

Figure 3. Comparison of 2004 and 2009 age-specific HIV prevalence rates in adults aged 15 years or older in rural South Africa.

(A) 2004 HIV prevalence rates in adults aged 15 years and above in rural South Africa. (B) 2009 HIV prevalence rates in adults aged 15 years and above in rural South Africa.

(A) is adapted from [17].

HIV incidence

Data on HIV incidence rates in mature adults are even more limited than prevalence estimates due to the fact that longitudinal HIV surveys commonly only follow younger adults aged 15–49 years [2]. Secondly, incidence reporting requires case-reporting systems that are largely absent in developing countries, unlike in developed countries. In the USA in 2006, 11% of all new cases were in mature adults, with evidence of increased incidence [3]. One of the few reports on incidence in mature adults in Africa, coming from Analysing Longitudinal Population-based HIV/AIDS Data on Africa (ALPHA) network sites based on five longitudinal community-based studies (Uganda, two sites: 1990–2005, Tanzania: 1994–2004; Zimbabwe: 1999–2004; and South Africa: 2004–2005), showed secondary peaks of incidence in mature adults [18], while a survey in rural South Africa estimated a 0.5% incidence rate in those aged over 50 years, which was higher in men (0.9%) than in women (0.4%) [2], with incidence cases observed even in those aged over 65 years. Although case reports in the USA and the WHO European region show an increase in incident cases [3], it is unclear whether the same applies to sSA due to the lack of incidence trend data. In countries with diverse racial groups such as South Africa, it would be beneficial for incidence studies to incorporate the different racial groups. However, HIV incidence is highest among black South Africans, and there are many more black citizens (79.4%) [103] than any other racial group in South Africa, so the national incidence will still be driven by the incidence in black South Africans.

HIV risk & transmission in mature adults

Several biological and behavioral factors put mature adults at high risk of becoming HIV infected; first, the thinning of the vaginal wall after menopause increases the risk of sexual transmission and acquisition [19]; second, having multiple sexual partners coupled with low condom use [8,9]; and third, practices of wife inheritance, where the widow marries the deceased’s relative, are common in many parts of sSA [3,8,15,16,108]. In sSA, the dominant mode of HIV transmission in mature adults is heterosexual. The risk of transmission and acquisition within marriage is high due to low condom use within the marriage relationship irrespective of other existing extramarital relationships. In serodiscordant couples, low condom use leads to high transmission risk, even in the absence of extramarital relationships [3,15,108,109]. This raises concerns about increased HIV risk in mature adults, who are a group with higher marriage rates than younger age groups and lower condom use, resulting in high risk of the uninfected partner in a married relationship becoming infected [3].

HIV risk in mature adults may be high as a result of males aged over 50 years engaging in unprotected sex and having multiple partners. In this group, only 39.9% in South Africa and 7.9% in Ghana report condom use at last sex act, a proportion lower than in those aged 15–49 years. Similar findings of low condom use and multiple sexual partners have also been reported in Benin, Democratic Republic of Congo and Nigeria [8,108]. In addition, a South Africa national survey with approximately 21,000 individuals reported high percentages of multiple sexual partners, with 7.5% of males aged 50 years or older reporting this in 2002, a proportion that rose to 9.8% in 2005. Even though this proportion decreased to 3.7% in 2008, the proportion for women aged 50 years and above, although not statistically significant, rose from 0.6% in 2005 to 0.8% in 2008 [108]. In 2010 in rural South Africa, 152 out of 1349 men and 96 out of 2768 women reported having two sexual partners, although this number was inclusive of adults in younger age groups [20].

Further increasing the HIV risk is the fact that, contrary to misconceptions that mature adults are not sexually active [8,19], many mature adults are indeed sexually active and hence are prone to HIV transmission and acquisition [3]. A 2005 South African HIV prevalence and behavior survey reported 41 and 36% of mature adults being sexually active in the last 12 months and last month, respectively [9]. In the same report, although reported sexual activity declined with age, 9% of men and 3% of women still reported being sexually active at the age of 70 years and above. However, even though mature adults have less frequent sex compared with younger adults, they are more likely to engage in risky sexual behaviors, as discussed earlier. Furthermore, mature adults may have sexual partners considerably younger than themselves, ranging from 5-year age gaps in women aged >40 years [20] to as much as 20-year age gaps in 17% of men aged 70 years or older and 6.4% of men aged 60–69 years [9], which raises concerns of increased HIV exposure risk in this age group, even though their own prevalence may be relatively low. Transmission in such cases is no longer driven only by the underlying HIV prevalence in mature adults, but also by that in the age group with which they mix sexually.

This risky sexual behavior may increase the probability of HIV transmission and acquisition in mature adults. This may also translate into high risks of acquiring sexually transmitted infections (STI), which increase the risk of HIV transmission in all age groups. Many mature adults in sSA are poor [21] and may not have the resources to seek medical attention; hence, STIs can go untreated, further driving HIV transmission and underscoring the need for sexual behavior change interventions in mature adults.

HIV prevention strategies

Misconceptions about mature adults not being sexually active [8,19] imply that they remain unrecognized as an HIV risk group, leading to their neglect in addressing HIV issues and potentially excluding them from accessing HIV prevention, treatment and care programs. As such, it is quite sobering that high proportions of males and females aged 50 years or older report having little HIV knowledge in terms of HIV transmission [19,108], possibly due to HIV programs not reaching this age group and probably explaining why there is more high-risk sexual behavior in the age group compared with younger age groups. Too often, the responsibilities of mature adults in preventing HIV cannot be realized because they do not have comprehensive sexual education and have unequal access to prevention methods. HIV prevention programs rarely focus on mature adults, married couples or serodiscordant couples [109]. Mature adults could benefit from HIV prevention interventions such as, but not limited to, in-depth HIV education messages on prevention, risk factors including unprotected sex, symptoms of HIV for early diagnosis and treatment and condom distribution at places that are accessible to them, such as elderly community meetings and community beer halls/beer spots. It is imperative to ensure that the messaging is age-relevant and comprehensible. New methods and forums for dissemination need to be employed, including use of community-based venues such as churches, community gatherings, pension pay-points and chronic health clinics. Mature adults could also benefit from community- and household-based HIV testing and counseling, as bringing the services to the people breaks the barriers to healthcare access.

Mature adults’ access to HIV-related services and information is limited, even though the largest share of new infections in many African countries occurs in older heterosexual couples [3,8]. In South Africa, there are currently no national health campaigns regarding STI/HIV prevention, testing and treatment tailored towards mature adults [9]; all current efforts ignore the specific needs of individuals aged 50 years or older. This situation in South Africa is perpetuated throughout the rest of sSA. Not much is known about sexual behavior among HIV-positive mature adults in developing countries, or about biological and cultural factors that increase the risk of transmission. Findings based on developed countries may not necessarily translate to the African context because sexual behavior is largely driven by the cultural and traditional norms of the society, which are themselves influenced by the socioeconomic status and political standing of that society [22].

Even though there is a high transmission probability of HIV in mature adults coupled with inadequate prevention strategies, empirical data on sexual behavior and biological and cultural risk factors remain insufficient and are urgently needed to inform on interventions to curb this transmission. In order to ensure that we maintain the progress that has been made so far in curbing the HIV epidemic, HIV responses must be age-specific yet universal enough to ensure relevance, coverage and access to all age groups.

Other age-related chronic morbidities for those over 50 years of age

Before discussing the implications of HIV in mature adults, it is worth understanding the underlying morbidity in mature adults that comes with natural aging in the absence of HIV. Further to the larger part of many peoples’ lives being lived in poor health [23,110], for mature adults, in the presence or absence of HIV, health is further affected by the presence of chronic conditions of aging. Progression through life entails biological and physiological changes: liver function declines due to a decline in liver mass and blood flow, and so does kidney function as glomerular filtration rates decline. There is also a decline in thymic function leading to decreased T-cell production, and a decline in cognitive function, gut absorption rate and bone density. Reduced hepatic and renal functions translate to reduced metabolism and excretion of toxic substances, while low thymic output results in a modest immune response to disease and treatment [12,15,16], ultimately leading to high chronic morbidity, which is also common in HIV-infected individuals irrespective of age, including, but not limited to, diabetes mellitus, cardiac diseases, hypertension, chronic kidney and liver disease, arthritis, depression and some cancers [15,24,25,111].

While degenerative chronic morbidities may have different individual and community level risk factors from those of communicable diseases [21,23] in the mature adult population, there may potentially be considerable overlap, as they are naturally prone to degenerative chronic conditions owing to age [4,7,26,27] and at the same time are exposed to infectious diseases such as HIV. Recently, in a South African survey of 3795 mature adults with 5.8% HIV prevalence, 50% of responders reported to have had at least one other illness in addition to being HIV infected, while 38% had at least two other illnesses [9]. Another study of the elderly in the slums of Nairobi also highlights the considerably poorer health in the face of HIV, a factor that is attributed to increases in lifestyle risk factors [28], such as tobacco smoking and physical inactivity. Comparable with HIV, chronic morbidity is associated with lifestyle risk factors; although chronic morbidity burden varies according to socioeconomic status, its distribution is also comparable with that of HIV, in that both morbidities place the heaviest burden is on poor communities in urban areas. Similarly, a report from one longitudinal demographic survey in Agincourt, rural South Africa [21] and two other surveys in the 2000s have confirmed high prevalence of hypertension, stroke, diabetes and obesity in adult populations [25]. This underlying morbidity is likely to have an impact on HIV progression as well as on ART, and treatment within this context may potentially interact with ART, giving rise to side effects and increased toxicity.

Data on causes of mortality, not only in the South African elderly but also in the rest of sSA, are generally few and mostly incomplete due to the fact the autopsies are rarely performed and many deaths in rural areas go unreported, hence the morbidity burden in mature adults cannot be accurately inferred from mortality causes alone and so the morbidity burden remains underestimated. The epidemiology of chronic morbidity is likely modified in the presence of HIV and ART and leads to a population with a dual burden of communicable and noncommunicable diseases [21,25]. There is a need for more studies quantifying the morbidity burden in adults aged 50 years or older in sSA and its interactions with HIV and ART to inform on health service integration, especially in resource-poor settings where health systems are overstretched and prioritization is crucial in an effort to deliver essential healthcare.

HIV infection & ART in the mature adult

Mature adults now comprise a significant proportion of people enrolling in HIV treatment programs in sSA, yet outcomes after initiation of ART for these older adults have not been well described in these settings. The WHO recommends ART initiation at CD4 count thresholds of <350 cells/μl or WHO disease stage IV, or ART should begin at WHO disease stage I/II if the CD4 count is less than 200 cells/μl [112]; however, treatment eligibility cut-offs vary widely across sSA. Most countries still use a threshold of 200 cells/μl, with the exception of countries such as Botswana. The standard triple-ART regimen at initiation consists of two nucleoside reverse transcriptases and one non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase.

Individuals with HIV may now live long enough to experience HIV as a chronic disease with competing risks from aging, ART drug toxicities and comorbid chronic diseases [6,8,12,15,16]. Available data from developed countries suggest that many aspects of natural aging or other chronic conditions may be negatively influenced by chronic HIV and ART [14–16,19]; however, this area is still controversial and requires further prospective studies to determine whether HIV results in early aging, and what ART contributes to that process. In Africa, there is limited understanding of comorbidities and drug interactions between ART and other aging-related chronic treatments. It is possible that these may be in line with what is observed in the USA and Europe, but extrapolation of data should be performed cautiously since morbidity is widely variable across different socioeconomic groups, genders, races and qualities and availabilities of healthcare at national and local levels.

Comorbidities, drug interactions & drug toxicities

Data from developed countries show that not only does HIV modify comorbid conditions in older people and their management, but also the occurrence of pre-existing morbidities raises important questions pertaining to when to start treatment in mature adults [19,29]. Complexity is added by the fact that older patients have decreased renal and liver function, hence there is less ability to break down and excrete by-products of the triple ART drugs. Combined with the effects of other chronic therapies, this raises concern regarding altered drug metabolism, drug–drug interactions and increased toxicities, including, but not limited to, diabetes, hepatotoxicity, renal insufficiency, dyslipidemia, neuropathy and lactic acidosis [26,30]. Kidney disease is important in mature adults on ART because of the kidneys’ major role in excreting drug metabolites, in the absence of which drug toxicities arise, hence the existence of substantial reports on this [12,31–35]. The prevalence of ART-driven kidney disease in HIV patients in both developing and developed countries is high [12,31–35]. Fabian and Naicker gave varying estimates of HIV-driven kidney disease in South Africa (6%), Nigeria (26%), Zambia (33.5%) and Kenya (20–48.5%) [32], although the extent to which these differences can be attributed to data quality, different research methodologies and diagnostic limitations remains uncertain and requires further investigation. The extent to which other comorbid ities and drugs interact with ART in sSA remains largely undocumented. It is quite possible that there is only limited development of side effects and that the benefits of ART in the presence of other drugs far outweigh the risks of side effects due to drug interactions.

Although there are no available data in sSA, studies in older adults in developed countries show that HAART toxicities affect virtually all organ systems [24], but few studies have examined the safety and optimal dosages of HAART specifically in mature adults [15,19], as clinical trials usually exclude mature adults. Onset of drug efficacy is potentially reduced in mature adults due to slower gastrointestinal efficiency, and hence reduced absorption rates and subtherapeutic drug levels. In addition, immune response is suboptimal since thymic volumes – that is, T-cell production – is reduced by 45 years of age and only minimal after 55 years of age [16]. This logically raises an important question of whether ART should be started early, before major CD4 cell depletion occurs, to try and preserve the chance of clinical and immunological success [15]. However, this question needs to be critically assessed in light of underlying comorbidities and possible drug effects and interactions, especially in resource-limited settings where there are limited alternative drug regimes. Clinicians may be caught in a ‘catch-22’ situation where they have no substitute regimen for these adults in cases of treatment failure or reaction following early initiation.

HIV infection later in life results in more rapid progression towards AIDS and shorter survival. This effect was especially marked in the pre-ART era, with life expectancy after HIV infection decreasing from 13 years in those aged 5–14 years to 4 years in those aged 65 years or older at time of infection [14,36–38]. A few studies in sSA have assessed survival by age in the pre-ART era: in Uganda and Tanzania, median survival was 12.8 years in those aged 15–24 years compared with only 5.6 years in those aged 45 years or older, while in South African miners, survival fell from 11.5 to 6.3 years in the same age groups [39]. This may be due to the reduced immune function in mature adults [16]. Worldwide, data relating to age-driven HIV progression quantifying the contribution of age at ART initiation to decline in long-term survival in the post-ART era are limited, and data on mortality outcomes by age are conflicting. Rapid progression, together with the issues surrounding ART treatment complications (reduced intensity and rapidity of immunological response despite good viral suppression [3,15,32,33], possible drug interactions and drug toxicities [12,29]) and coupled with age-related comorbidities [14,40], makes the mature adult special and different compared with young adults. HIV treatment and care ought to be customized to cater specifically for the needs of mature adults instead of putting them under one blanket ‘adult’ group with younger adults. Patient management is complicated in the absence of empirical data to guide clinicians on how to administer ART and monitor its effects in the mature adult. A reduction in comorbidities and consequently a reduction in treatment burden may potentially enhance ART adherence and improve treatment outcomes.

Mortality

Since the introduction of ART, there have been conflicting data on mortality outcomes for older individuals. A decade after the introduction of ART, a French study reported a 1.5-times increased mortality risk in patients aged over 50 years at time of ART initiation compared with younger patients [15]. Similar to this and other resource-rich countries, African studies have reported a positive association between increasing age at ART initiation and either AIDS or mortality [41–43], while others report no difference in mortality with varying age at ART initiation [34,35,44,45]. Age at both infection and treatment commencement is a major determinant of mortality for many diseases, including HIV infection, but the effect of age itself on other prognostic factors is not often studied directly [36,46]. The excess mortality in HIV-positive mature adults is not completely accounted for by the increased mortality that comes with aging [113], indicating that, as well as age, there may be other factors contributing to mortality. Age-associated ART complications and modest immunological responses to ART may be associated with more rapid progression to AIDS, which may surreptitiously drive increased mortality in mature adults.

Antiretroviral Therapy in Lower Income Countries (ART-LINC), a collaboration of HIV treatment cohorts in lower-income countries, reports a twofold increased mortality risk in those aged 50 years or older compared with 16–29-year-old subjects, which is consistent with the 58% increased mortality reported in the Free State in South Africa compared with 20–29-year-old subjects [43,47]. Other studies from sSA, including South Africa, Zambia and Senegal, have reported no clear association between age and mortality on ART, even with considerable sample sizes [45,47–49]. Comparisons across studies are complicated by the use of different age categories and different follow-up periods. Moreover, these studies have included age as an explanatory variable rather than explicitly assessing mortality within and between younger and older age groups.

Cause-specific mortality data are largely lacking in sSA, and vital registration systems do not have detailed mortality causes [21]. In a verbal autopsy study in rural Kenya, HIV was the cause of death in 27% of people aged 50 years or older and was the leading cause of death up to the age of 70 years [50]. Other than this study, studies defining cause of death in adults aged 50 years or older by HIV status both pre- and post-ART are scarce, and robust data are needed. Recent publications from Europe and North America show that age-associated non-HIV-related diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, non-AIDS-defining cancers, hepatitis, hyperlipidemia, diabetes and kidney and liver disease, are growing causes of death in people living with HIV, while AIDS-defining causes continue to fall due to ART [51,52]. Older age was strongly associated with non-AIDS defining mortality, implying that the process of aging will become a dominant factor in the mortality of HIV-positive individuals in the next decade as AIDS-related mortality decreases with therapy in this age group and age-related mortality increases with population aging. A few African-based reports also highlight a decline in AIDS-related mortality in all adults; however, AIDS still remains the major cause of death in both mature and younger adults with HIV [13,25,50], and there is limited emphasis on specific non-AIDS-defining causes. In these reports, the relative contributions of age to these morbidities and the likely variations in the younger and older adults are lacking.

Treatment adherence issues in older persons

Studies on adherence to ART have reported low levels of adherence across all age groups, with 29–59% of chronic patients reported as non adherent [53]. The majority of older people present with chronic–degenerative conditions, cognitive decline and treatment thereof. In addition to this are the evident side effects of ART and drug interaction factors likely to negatively impact on ART adherence and result in suboptimal treatment response. Memory problems increase with age, and the risk of dementia is exacerbated in the presence of HIV [15,19], which may lead to mature patients forgetting to take treatment at predefined time intervals, especially when they do not have a younger adult to remind them. Myths that HIV does not affect mature adults due to a lack of sexual activity [8,19] may reduce chances of disclosure to individuals who could potentially offer ART adherence support to the HIV-infected mature adult, a factor that negatively influences adherence. Increased viral suppression in mature compared with young adults is often attributed to better treatment adherence in older ages [15], an attribution that may be false in light of previously mentioned factors and the fact that no longitudinal studies have exclusively looked at treatment adherence in mature adults and how it compares with that in younger adults. In sSA, the main focus since the introduction of ART has been to deliver treatment to those in most need, and not the longitudinal monitoring of those on ART. With ART delivery systems now available, there is a need to put more emphasis on monitoring adherence issues in both young and mature adults. Studies into this may reveal risk factors for nonadherence that may potentially inform on intervention strategies.

Healthcare utilization

The current scenario makes it difficult for mature adults to seek medical advice for sexually related health conditions, including HIV, given that it is generally assumed that mature adults are sexually inactive and thus not at risk. Even if they do seek medical advice, neither healthcare workers nor the mature adult themselves proactively discuss sexual health, and healthcare workers are less likely to discuss HIV issues with mature adults or suggest HIV testing [3,8,12].

With most HIV services placed in urban areas and the majority of mature adults (especially those of post-retirement age) in sSA live in rural areas [11], healthcare services may not be available where they are needed. Rapid HIV progression may mean that by the time mature adults seek healthcare, HIV disease is already advanced. In France, adults aged between 50 and 60 years were nearly three times more likely to access care late, while a recent report from rural South Africa showed that, compared with younger adults, retention in care prior to ART initiation (during CD4-count monitoring) was lower in females aged above 55 years, irrespective of initial CD4 count, and was lower in males >55 years old with CD4 counts >500 cells/μl, thus reducing the likelihood of timely initiation of ART [54]. Mature adults are only a fifth as likely to have been HIV tested compared with individuals in their 20s, due to reports that they consistently report fewer symptoms than their younger counterparts [19], and hence these few symptoms are less likely to be interpreted as HIV. Symptoms associated with aging, such as anemia, weight loss, neuropathy and memory loss, overlap with those of AIDS [15,19], thus healthcare workers might investigate other avenues linked to aging morbidities before interpreting illness as HIV. Although it may be essential for mature adults to initiate ART early, interventions first need to be implemented that will ensure that HIV services are mature-age friendly so as to enable mature adults to seek HIV services early. Furthermore, healthcare workers must be quick to consider the possibility of HIV in these patients. Without these steps, early diagnosis and treatment in mature adults will remain unattainable.

Whether rapid progression and high mortality are driven by older age or by late diagnosis, and hence delay access to care by older persons [15,25], warrants further investigation. There is a need to assess HIV disease stages in older persons at the time of HIV diagnosis to understand whether adverse outcomes are due to biological factors or access issues.

Imperative future planning for an aging HIV-infected population

Planning and preparing for the imminent epidemic of HIV-positive mature adults in sSA is complicated and will need to be nationally and culturally appropriate. Irrespective of age, sSA generally has a heterogenous HIV epidemic, and while countries like Uganda have a smaller epidemic that they have managed to turn around, others, such as Malawi, Swaziland and Zambia, carry a larger epidemic that they have not managed to control. These differences are attributable, but not limited to, variability in cultural paradigms, economic conditions, political instability and public health and social policies [22]. Efforts to address the HIV epidemic in mature adults will need to be multifaceted, taking into account the diverse countries within sSA, the heterogeneity of the epidemic and the prevailing situations in each country. Table 1 highlights possible strategies for tackling the imminent aging of the HIV-positive population.

Table 1.

Current issues relating to HIV in mature adults in sub-Saharan Africa and possible future planning strategies for combating HIV in mature adults.

| Current issues relating to mature adults |

Possible solutions and future planning strategies |

|---|---|

| Growing proportion of HIV-infected mature adults |

Governments need to be aware of this imminent situation and prepare for the relevant health and social needs that come with this paradigm Resources need to be devoted to the development of HIV prevention strategies Health policy changes at national and international levels to incorporate and cater for the needs of mature adults. These may be inclusive of early treatment initiation and the expansion and integration of HIV and geriatric care to reduce rapid disease progression and lower AIDS-related mortality |

| Limited empirical data on HIV prevalence and incidence |

Incentives for more research in HIV-positive mature adults Partnerships between academic institutions and public and private geriatric care centers to better understand HIV in mature adults National health surveys to include people aged 50 years or older |

| Limited awareness that HIV is a reality in mature adults and sexual transmission is considerable in this age group HIV discussions are often stifled, hindering prevention efforts |

Involvement of mature adults in HIV education campaigns may be the key to sustainable HIV awareness in mature adults as it facilitates broadening of awareness activities, draws attention to mature adults, reduces stigma and enhances services HIV in mature adults should be openly discussed in all forums and acknowledged as a reality; HIV messaging should include pictures of mature adults Culture-specific structured preventative strategies tailored toward mature adults involving provision of HIV education, including the role of sexual behavior in HIV acquisition, should be implemented at geriatric centers where mature adults present for other age-related morbidities Improved condom distribution in places that are accessible to mature adults, such as church gatherings or even household distribution in high-prevalence communities |

| Late HIV diagnosis possibly due to limited access to HIV-related information and exclusion from HIV prevention and testing services |

Community awareness will inevitably drive early diagnosis and treatment Active HIV case-finding through routine testing of mature adults attending various health centers for other non-AIDS-related ailments or through community- and home-based HIV counseling and testing Increasing responsiveness in healthcare workers to vigilantly check for HIV in mature adults rather than ascribing clinical symptoms to aging |

| Complications of antiretroviral therapy including drug interactions and drug toxicities in light of reduced physiological function and underlying comorbidities; although most of what we know is based on developed countries |

Clinicians must be cognisant of drug interactions and potential adverse effects of antiretroviral therapy when initiating and monitoring antiretroviral therapy in mature patients Intensive training of HIV healthcare workers on the clinical management of basic geriatric conditions in the context of HIV and antiretroviral therapy, as well as HIV training for geriatricians Comprehensive geriatric assessments in HIV-positive mature adults and for close monitoring of comorbidities and drug interactions while on HIV therapy, especially during the initial phases, when mortality has been reported to be particularly high in this age group It might be worth evaluating in prospective studies new antiretroviral therapy drug regimens that may potentially be less toxic and interact less with other coadministered geriatric drugs |

| Reduced healthcare utilization, particularly in poorer communities |

Imperative need for governments to significantly invest in expanding and strengthening healthcare services infrastructure, services and staff in sub-Saharan Africa; the currently available healthcare resources are inadequate and overwhelmed Community education through various community channels, such as community elderly meetings, church gatherings and pension pay points, on the need for health checks Home-based care might be the best option for HIV-infected mature adults, especially during the initial phases of antiretroviral therapy; however, it is imperative to invest in comprehensive geriatric and HIV training of home-based care workers Integration of healthcare services to make healthcare a ‘one-stop shop’ where mature adults only need to visit one healthcare facility for both geriatric and HIV care HIV healthcare facilities should be made mature age-friendly, including employing healthcare workers who are in the mature age category, as this may potentially make sexual behavior and HIV-related discussions more palatable for the mature adult |

Conclusion

There is a lack of evidence on HIV in mature adults in sSA regarding prevention, transmission, diagnosis and treatment issues, including the impact of ART on health outcomes. The impact of the HIV pandemic in children and adults of reproductive age has been studied extensively, but little is known about older people in sSA. Much of what we know from developed countries is likely not transferable to other settings with different patterns of the HIV epidemic, available ART therapies, economies, specific risk factors for communicable and chronic conditions and mortality situations. HIV is a global threat, but etiologies of patient outcomes are likely to be multifaceted and locally and regionally variable, demanding a tailored response. Much can be learnt from approaching chronic HIV infection with an aging perspective [31], considering that there is limited understanding of the relative contributions that age-associated differences in immunology, virology, access to treatment and susceptibility to comorbid diseases have on long-term outcomes.

Understanding the frequency of and factors likely to be associated with HIV will inform relevant health and social services policy regarding development and implementation, catering for the special needs of older adults in sSA in this era of health systems integration. Adverse outcomes must be understood, as they place an additional burden on the provision of efficient care in both the private and public health sector and should to be taken into account in health planning. Gaps in knowledge may perpetuate poor health provision for HIV-infected mature adults in resource-limited settings where resources are focused on already identified priority areas.

Future perspective

Given the considerably high HIV prevalence, risky sexual behavior and significant incidence rates in mature adults, this group can no longer be ignored in the responses to the HIV epidemic. The aging of the HIV-infected population requires greater efforts to integrate the needs of mature adults into responses to the HIV epidemic as we move into the future. Studies are needed to identify and understand the specific HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care needs of mature adults. Mature adults are likely to present with underlying aging-comorbid conditions, which may potentially be exacerbated in the presence of HIV and ART, making primary prevention with appropriate screening for common risk factors, including but not limited to hypertension, hyperlipidemia, impared kidney function or impaired glucose tolerance, imperative.

Few service providers have planned for an aging African HIV-positive population, and if this does not change, meeting the complexities of geriatric care for HIV-infected adults in future will further challenge overwhelmed health systems and will require that health systems be integrated and optimally efficient.

Executive summary.

▪ Despite increased recognition of the increasing burden of HIV in mature age groups and the likely complexities associated with aging and HIV, we still know little in terms of possible antiretroviral therapy (ART) response side effects, comorbidities and drug toxicities, nor do we understand the sexual behavior and societal diversity in mature adults and their likely impact on the HIV epidemic.

▪ Use of ART in mature adults may be complicated by multiple chronic comorbidities and coadministered non-HIV medicines resulting in drug interactions and hence increased risk of adverse drug events. This complicates the already challenging medical management of HIV, even more so in developing countries, where there are limited HIV drug regimens, their side effects are not well understood and no specific guidelines exist for the management of HIV in this age group.

▪ The mistaken assumption that mature adults are not sexually active or only minimally active renders them unlikely to receive sexual health education and care. Coupled with this is the fact that aging symptoms overlap with those of HIV, hence healthcare workers are more likely to neglect the possibility of occult HIV in mature adults, leading to perilously delayed diagnosis in a population where HIV progression is rapid.

▪ Longitudinal studies will help us to understand the interactions between the timing of diagnosis and ART initiation, the interaction of HIV, ART and comorbidities and may underscore missed opportunities requiring interventions.

▪ More research is urgently needed on the whole topic of HIV in mature adults, with studies needed to focus on the usefulness of integrated geriatric and HIV services and the role of comprehensive geriatric assessments in HIV-positive patients, as well as comprehensive HIV screening in geriatric patients and their impact on ART outcomes.

▪ On the cusp of the fourth decade of the HIV epidemic, the world has turned the corner – it has halted and begun to reverse the spread of HIV (Millennium Development Goal 6.A). The question remains as to how quickly the response can chart a new course towards the UNAIDS vision of zero discrimination through universal access to effective HIV prevention, treatment, care and support. Stigma and discrimination, lack of access to services and bad laws can make epidemics worse. HIV directly affects all ages throughout life, and the exclusion or neglect of any age group may actually compromise the successes achieved thus far in addressing the epidemic. This is even more critical in the presence of concurrent or sequential intergenerational and intragenerational sexual activity, where the successes earned in younger age groups may be annulled by failures in mature age groups.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Abraham Malaza (Africa Centre HIV surveillance project leader).

The Africa Centre for Health and Population Studies is funded by a core grant from the Wellcome Trust (Grant number 082384/Z/07/Z) (www.wellcome.ac.uk). The funders had no role in the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Bibliography

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

▪ of interest

▪ ▪ of considerable interest

- 1.Murray C, Lopez A. Mortality by cause for eight regions of the world: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997;349:1269–1276. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07493-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wallrauch C, Barnighausen T, Newell M-L. HIV infection of concern also in people 50 years and older in rural South Africa. S. Afr. Med. J. 2010;100(12):821–824. doi: 10.7196/samj.4181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmid GP, Williams BG, Garcia-Calleja JM, et al. The unexplored story of HIV and aging. Bull. World Health Organ. 2009;87(3):162–162A. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.064030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pardi GR, Nunes A, Preto R, Canassa P, Correia D. Profile of adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy of patients older than 50 years old. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2009;52(2):301–302. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b065ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Danielson ME, Justice AC. Veterans Aging Cohort Study (VACZ) meeting summary. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2001;54:S9–S11. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00441-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gebo KA. HIV infection in older people. BMJ. 2009;338:B1460. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Negin J, Wariero J, Cumming R, Mutuo P, Pronyk P. High rates of AIDS-related mortality among older adults in rural Kenya. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2010;55(2):239–244. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181e9b3f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Negin J, Cumming R. HIV infection in older adults in sub-Saharan Africa: extrapolating prevalence from existing data. Bull. World Health Organ. 2010;88:847–853. doi: 10.2471/BLT.10.076349. ▪ Provides an overview of HIV prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa.

- 9.Peltzer K, Phaswana-Mafuya N, Mzolo T, Tabane C, Zuma K. Sexual behaviour, HIV status and HIV risk among older South Africans. Ethno. Med. 2010;4(3):163–172. ▪ ▪ One of the few papers in sub-Saharan Africa assessing sexual behavior and HIV risk knowledge in adults aged 50 years or older.

- 10.Schartz E, Ogunmefun C. Caring an contributing: the role of older women in rural South African multi-generational households in the HIV/AIDS era. World Dev. 2007;35:1390–1403. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mills E, Rammohan A, Awofeso N. Ageing faster with AIDS in Africa. Lancet. 2011;377(9772):1131–1133. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62180-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gebo K. Epidemiology of HIV and response to antiretroviral therapy in the middle aged and elderly. Aging Health. 2008;4(6):615–627. doi: 10.2217/1745509X.4.6.615. ▪ ▪ Detailed review of the complexities surrounding HIV and antiretroviral therapy in older adults.

- 13.Herbst AJ, Cooke GS, Barnighausen T, Kanykany A, Tanser F, Newell ML. Adult mortality and antiretroviral treatment roll-out in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Bull. World Health Organ. 2009;87(10):754–762. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.058982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manfredi R, Calza L, Cocchi D, Chiodo F. Antiretroviral treatment and advanced age: epidemiologic, laboratory and clinical features in the elderly. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2003;33(1):112–114. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200305010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grabar S, Weiss L, Costagliola D. HIV infection in older patients in the HAART era. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006;57(1):4–7. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nguyen N, Holodniy M. HIV infection in the elderly. Clin. Intervent. Aging. 2008;3(3):453–472. doi: 10.2147/cia.s2086. ▪ Detailed ana lysis of possible interactions between age-related comorbidities and HIV and antiretroviral therapy.

- 17.Welz T, Hosegood V, Jaffar S, Batzing-Feigenbaum J, Herbst K, Newell ML. Continued very high prevalence of HIV infection in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: a population-based longitudinal study. AIDS. 2007;21(11):1467–1472. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280ef6af2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaba B, Todd J, Biraro S, et al. Diverse age patterns of HIV incidence in Africa. Presented at: XVII International AIDS Conference; Mexico City, Mexico. 3–8 August 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kohli R, Klein R, Schoenbaum E, Anastos K, Minkoff H, Sacks H. Aging and HIV infection. J. Urban Health. 2006;83(1):31–41. doi: 10.1007/s11524-005-9005-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miles Q, Barnighausen T, Tanser F, Lurie M, Newell M. Age-gaps in sexual partnerships: seeing beyond ‘sugar daddies’. AIDS. 2011;25(6):861–863. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834344c9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kahn K, Tollman S, Thorogood M, et al. Older adults and the health transition in Agincourt, rural South Africa: new understanding, growing complexity. In: Cohen B, Menken J, editors. Aging in sub-Saharan Africa: Recommendations for Furthering Research. National Academic Press; Washington, DC, USA: 2006. pp. 166–188. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lau C, Muula A. HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. Croat. Med. J. 2004;45(5):402–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lopez A, Mathers C, Ezzati M, Jamison D, Murray C. Global Burden of Disease and Risk Factors. Oxford University Press; NY, USA: 2006. Measuring the global burden of disease and risk factors, 1990–2001; pp. 1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Christensen K, Doblhammer G, Rau R, Vaupel J. Aging populations: the challenges ahead. Lancet. 2009;374:1196–1208. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61460-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mayosi B, Flisher A, Lalloo U, Sitas F, Tollman S, Bradshwa D. The burden on non-communicable diseases in South Africa. Lancet. 2009;374:934–947. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61087-4. ▪ Classic paper detailing the burden of and trends in noncommunicable diseases in both young and mature adults in South Africa and highlights possible risk factors.

- 26.Rhee MS, Greenblatt DJ. Pharmacologic consideration for the use of antiretroviral agents in the elderly. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008;48(10):1212–1225. doi: 10.1177/0091270008322177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andrew C, David AC. Adverse effects of retroviral therapy. Lancet. 2000;356:1423–1430. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kyobutung C, Egondi T, Ezeh A. The health and wellbeing of older people in Nairobi’s slums. Glob. Health Action. 2010;S2:45–53. doi: 10.3402/gha.v3i0.2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gebo K. HIV and aging: implications for patient management. Drugs Aging. 2006;23(11):897–913. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200623110-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Justice AC, Landefeld CS, Asch SM, Gifford AL, Whalen CC, Covinsky KE. Justification for a new cohort study of people aging with and without HIV infection. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2001;54:S3–S8. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00440-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cuzin L, Delpierre C, Gerard S, Massip P, Marchou B. Immunologic and clinical responses to highly active antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV infection aged >50 years. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007;45(5):654–657. doi: 10.1086/520652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fabian J, Naicker S. HIV and kidney disease in sub-Saharan Africa. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2009;5(10):591–598. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2009.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sabin CA, Smith CJ, Delpech V, et al. The associations between age and the development of laboratory abnormalities and treatment discontinuation for reasons other than virological failure in the first year of highly active antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med. 2009;10(1):35–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brinkhof MW, Dabis F, Myer L, et al. Early loss of HIV-infected patients on potent antiretroviral therapy programs in lower-income countries. Bull. World Health Organ. 2008;86(7):559–567. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.044248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Etard JF, Ndiaye I, Thierry-Mieg M, et al. Mortality and causes of death in adults receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy in Senegal: a 7-year cohort study. AIDS. 2006;20(8):1181–1189. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000226959.87471.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Babiker AG, Peto T, Porter K, Walker AS, Darbyshire JH. Age as a determinant of survival in HIV infection. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2001;54(Suppl. 1):S16–S21. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00456-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glynn JR, Sonnenberg P, Nelson G, et al. Survival from HIV-1 seroconversion in Southern Africa: a retrospective cohort study in nearly 2000 gold-miners over 10 years of follow-up. AIDS. 2007;21(5):625–632. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328017f857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eligibility for ART in Lower Income Countries (eART-LINC) Collaboration. Wandel S, Egger M, Rangsin R, et al. Duration from seroconversion to eligibility for antiretroviral therapy and from ART eligibility to death in adult HIV-infected patients from low and middle-income countries: collaborative ana lysis of prospective studies. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2008;84(Suppl. 1):I31–I36. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.029793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Todd J, Glynn J, Marston M, et al. Time from HIV seroconversion to death: a collaborative ana lysis of eight studies in six low and middle-income countries before highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2007;21:S55–S63. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000299411.75269.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tumbarello M, Rabagliati R, De Gaetano K, Bertagnolio S, Tamburrini E, Cauda R. Older HIV-positive patients in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: changing of a scenario. AIDS. 2003;17(1):128–131. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200301030-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lawn SD, Little F, Bekker LG, et al. Changing mortality risk associated with CD4 cell response to antiretroviral therapy in South Africa. AIDS. 2009;23(3):335–342. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328321823f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Toure S, Kouadio B, Seyler C, et al. Rapid scaling-up of antiretroviral therapy in 10,000 adults in Cote d’Ivoire: 2-year outcomes and determinants. AIDS. 2008;22(7):873–882. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f768f8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tuboi SH, Pacheco AG, Harrison LH, et al. Mortality associated with discordant responses to antiretroviral therapy in resource-constrained settings. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2010;53(1):70–77. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c22d19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brinkhof MW, Boulle A, Weigel R, et al. Mortality of HIV-infected patients starting antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: comparison with HIV-unrelated mortality. PLoS Med. 2009;6(4):E1000066. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stringer JS, Zulu I, Levy J, et al. Rapid scale-up of antiretroviral therapy at primary care sites in Zambia: feasibility and early outcomes. JAMA. 2006;296(7):782–793. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.7.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.The Collaboration of Observational HIV Epidemiological Research Europe (COHERE) Study Group Response to combination antiretroviral therapy: variation by age. AIDS. 2008;22(12):1463–1473. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f88d02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fairall LR, Bachmann MO, Louwagie GM, et al. Effectiveness of antiretroviral treatment in a South African program: a cohort study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2008;168(1):86–93. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brinkhof MW, Pujades-Rodriguez M, Egger M. Mortality of patients lost to follow-up in antiretroviral treatment programs in resource-limited settings: systematic review and meta-ana lysis. PLoS One. 2009;4(6):E5790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Macpherson P, Moshabela M, Martinson N, Pronyk P. Mortality and loss to follow-up among HAART initiators in rural South Africa. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2009;103(6):588–593. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Negin J, Wariero J, Cumming R, Mutuo P, Pronyk P. High rates of AIDS-related mortality among older adults in rural Kenya. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2010;55:239–244. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181e9b3f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.The Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration Causes of death in HIV-1-infected patients treated with antiretroviral therapy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010;50:1387–1396. doi: 10.1086/652283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.De Wit S, Sabin C, Weber R, et al. Incidence and risk factors for new-onset diabetes in HIV-infected patients. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1224–1229. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dunbar-Jacob J, Mortimer-Stephens MK. Treatment adherence in chronic disease. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2001;54:S57–S60. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00457-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lessells R, Mutevedzi P, Cooke G, Newell M. Retention in HIV care for individuals not yet eligible for antiretroviral therapy: rural KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. J. Acquir Immune Defic. Syndr. 2011;56(3):E79–E86. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182075ae2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Websites

- 101.Kinsella K, Ferreira M. International Brief – Aging trends: South Africa. 1997 www.census.gov/ipc/prod/ib-9702.pdf (Accessed January 2011)

- 102.Statistics South Africa Mid-year population estimates, South Africa. 2006 www.statssa.gov.za/publications/statsdownload.asp?PPN=P0302&SCH=3713 (Accessed October 2010)

- 103.Statistics South Africa Statistical release. Mid-year population estimates. 2010 www.statssa.gov.za/publications/statsdownload.asp?PPN=P0302&SCH=4696 (Accessed October 2010)

- 104.Helpage International UNGASS indicators: where are the over 50s. 2008 Jun; www.globalaging.org/health/world/2008/UNGASSbriefing.pdf (Accessed January 2011)

- 105.UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. 2010 www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2010/20101123_globalreport_en.pdf (Accessed January 2011)

- 106.WHO Impact of AIDS on older people in Africa: Zimbabwe case study. 2002 www.who.int/ageing/projects/hiv/zwe_study/en/index.html (Accessed February 2011)

- 107.Report on the global AIDS epidemic. http://data.unaids.org/pub/GlobalReport/2008/JC1511_GR08_ExecutiveSummary_en.pdf (Accessed October 2010)

- 108.Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi LC, et al. South African national HIV prevalence, incidence, behaviour and communication survey 2008: a turning tide among teenagers? 2009 www.mrc.ac.za/pressreleases/2009/sanat.pdf (Accessed December 2010)

- 109.UNAIDS Getting to zero: 2011–2015 strategy Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. 2010 www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2010/JC2034_UNAIDS_Strategy_en.pdf (Accessed February 2010)

- 110.National Health Insurance Note 2. Econex Trade, Competition and Applied Economics. 2009 www.mediclinic.co.za/about/Documents/ECONEX%20NHI%20note%202.pdf (Accessed January 2010)

- 111.National Institute of Aging, NIH Why population aging matters: a global perspective. 2007 www.nia.nih.gov/NR/rdonlyres/9E91407E-CFE8-4903-9875-D5AA75BD1D50/0/WPAM.pdf (Accessed October 2010)

- 112.WHO Scaling up of antiretroviral therapy in resource limited settings: treatment guidelines for a public health approach. 2004 www.who.int/hiv/pub/prev_care/en/arvrevision2003en.pdf (Accessed January 2011) [PubMed]

- 113.Collaborative Group on Aids Incubation and HIV Survival Age at time of seroconversion reported to be key prognostic factor in era before HAART in newly published study. www.natap.org/2000/june/age_at_time060500.htm (Accessed May 2010)