Abstract

Several flavonoids have been reported to be proteasome inhibitors, but whether prenylated flavonoids are able to inhibit proteasome function remains unknown. We report for the first time that Sanggenon C, a natural prenylated flavonoid, inhibits tumor cellular proteasomal activity and cell viability. We found that (1) Sanggenon C inhibited tumor cell viability and induced cell cycle arrest at G0/G1 phase; (2) Sanggenon C inhibited the chymotrypsin-like activity of purified human 20S proteasome and 26S proteasome in H22 cell lysate, and Sanggenon C was able to dose-dependently accumulate ubiquitinated proteins and proteasome substrate protein p27; (3) Sanggenon C-induced proteasome inhibition occurred prior to cell death in murine H22 and P388 cell lines; (4) Sanggenon C induced death of human K562 cancer cells and primary cells isolated from leukemic patients. We conclude that Sanggenon C inhibits tumor cell viability via induction of cell cycle arrest and cell death, which is associated with its ability to inhibit the proteasome function and that proteasome inhibition by Sanggenon C at least partially contributes to the observed tumor cell growth-inhibitory activity.

Keywords: Sanggenon C, proteasome inhibitor, cell death, cell cycle, flavonoid

2. INTRODUCTION

Flavonoids are a group of chemical entities of benzopyrone derivatives widely distributed in the plants. More than 4,000 flavonoid derivatives from nature have been reported, indicating their chemical diversities. Flavonoids are mainly classified as chalcones, flavan-3-ols, flavanones, flavones and flavonols, isoflavones, and biflavonoids (1). They possess various biological and pharmacological activities, which include anti-cancer, anti-microbial, anti-viral, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, and antithrombotic activities. Prenylated flavonoids and/or flavonoid Diel-Alder adducts also exist widely in natural products (2). Of their biological activities, the anti-inflammatory capacity of flavonoids has long been utilized in Chinese medicine. It has been shown that many of flavonoid molecules possess anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer activities on various animal models of inflammation or cancer (1). There have been several proposed cellular mechanisms of action explaining in vivo anti-inflammatory or anti-cancer activities of flavonoids. In fact most of the reported natural flavonoids have multiple molecular targets in the cell. Therefore, plant-derived compounds especially flavonoids have great potential to be developed into anti-cancer or anti-inflammation drugs because of their multiple mechanisms and low side effects (3).

Proteasome inhibition has been demonstrated as a novel therapeutic strategy in multiple disease models, including fibrosis (4), inflammation (5), ischemia-reperefusion injury (6), myocardial hypertrophy (7) and cancer (8). Proteasome inhibitor bortezomib (Valcade or PS-341) has been approved by the United States FDA to treat multiple myeloma. Other proteasome inhibitors are now under clinical trials for cancer therapy (8). However, there were some associated toxicity observed in the clinical trials using bortezomib (8). Therefore, there is a need to search for novel proteasome inhibitors with decreased side effect. It is an attractive idea to identify and isolate novel natural proteasome inhibitors from medicinal plants. Many of the reported natural proteasome inhibitors belong to the flavonoid family (3). Among all these reported natural flavonoid proteasome inhibitors, an aromatic ketone structure plays a very important role for binding to the threonine residue at the N terminus (Thr 1) of the proteasome subunits and inhibiting the proteasomal activities (3, 9, 10).

Several flavonoids have been isolated from the stem bark of Morus cathayana (SANGPAIPI), including Sanggenon C. Sanggenon C is a flavanone Diel-Alder adduct compound. Up to now, there are only a few reports on the biological and pharmacological effects of Sanggenon C. It has been reported that Sanggenon C has anti-oxidant and anti-inflammation activities (2) and could inhibit TNF-alpha-stimulated cell adhesion and expression of VCAM-1 by suppressing the activation of NF-kappa B. It has also been proposed that Sanggenon C decreases ICAM-1 protein expression at a post-translational level (11). In addition, it was reported that Sanggenon C inhibited protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (12) and possessed the function to decrease blood pressure. Since Sanggenon C possesses the most potent cell toxicity among the flavonoids from Sangbaipi (13), it could serve as a candidate anti-cancer agent. The purpose of this study is to purify Sanggenon C from Chinese tranditional medicine Sangbaipi, to determine the cytotoxic effects of Sanggenon C on cancer cells, and to further examine whether Sanggenon C induces proteasome inhibition as one of the potential molecular mechanisms of action.

3. MATERIALS AND METHODS

3.1. Materials

TC/PI (propidium iodide) apoptosis detection kit and LDH detection kit were purchased from Keygen Company (Nanjing, China). H22, P388 and K562 cell lines were purchased from ATCC. Anti-ubiquitin, anti-p27, and anti-GAPDH antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti-PARP antibody was purchased from Cell Signaling.

3.2. Extraction and isolation of Sanggenon C

The cortex of Morus Alba L. was collected from the Tianmu Mountain, Zhejiang Province, China, in 2006 and was identified by Prof. Zhu Chen-chen. A voucher specimen (06-MAL) is deposited in the School of Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou University of Traditional Chinese Medicine. The UV Spectra were carried out on a Shimadzu UV-240 spectrophotometer. IR Spectra were recorded with an EQUINOX55 (Bruker) spectrophotometer. NMR spectra were recorded with Bruker Unity BRUKER 400 MHz. The cortex Mori of Morus Alba L. (5.0 kg, dried wt.) was extracted with hot ethanol (25L×3). The combined extracts were concentrated under reduced pressure to afford a brown extract (500 g). The ethanol extract was partitioned between EtOAc and H2O. The EtOAc soluble portion (152 g) was chromatographed on silica gel column using petroleum ether (PE)-Acetone mixtures as eluting solvent which yielded twelve fractions. The second fraction eluted with PE/ Acetone, 7:3 was further separated by using flash chromatography on silica gel (eluted with PE/ Acetone, 9:1) which gave Sanggenon C (209.8 mg). The purity of the isolated Sanggennon C was determined to be 99.5%.

3.3. Peptidase activity assay and cell-based proteasome activity assay

These in vitro and cell-based assays were performed as we previously described (14). A 20 microliter of Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) containing purified 20S proteasome (0.5 ninomolar) (from human erythrocytes, Enzo Life Sciences) or crude protein extracts (10 microgram protein) from the cultured cells were added to a total volume of 180 microliter Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) reaction buffer containing the synthetic fluorogenic peptide Suc-LLVY-aminomethylcoumarin (AMC) for the proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity. The reaction mixture was then incubated at 37°C for 90 min, followed by measurement of the fluorescence intensity of the free AMC using a luminescence microplate reader (Varioskan Flash 3001, Thermo, USA). The excitation and emission wavelengths for measuring free AMC were 360 nm and 436 nm, respectively.

To determine the effect of Sanggenon C on proteasomes in culture cells, a Promega cell-based assay was used. About 4,000 cells were treated with Sanggenon C at various concentrations at 37°C for 6 hours. The drug-treated cancer cells were then incubated with the Promega Proteasome-Glo Cell-Based Assay Reagent (Promega Bioscience, Madison, WI) for 10 minutes. The proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity was detected as the relative light unit (RLU) generated from the cleaved substrate in the reagent. Luminescence generated from each reaction was detected with luminescence microplate reader (Varioskan Flash 3001, Thermo, USA).

3.4. Cell culture

Murine (H22, P388) and human (K562) leukemia cells were cultured in RPMI1640 medium (Gibco) with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum, and maintained at 37 °C with 95% humidified air and 5% CO2. Human peripheral PMNCs from patients (n=3) with primary T-cell acute lymphocytic leukemia were separated by Ficoll solution and cultured in RPMI-1640 medium with 10% FBS. About 36 h later, the cells were plated in 6-well plates for following experiments. Supernatant was collected for LDH assay as described below. The patient consent form was completed by Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital.

3.5. LDH assay

LDH activity was performed as described previously (15). LDH activity in the collected medium was measured using the cytotoxicity detection kit (Keygen, Nanjing, China) by the reduction of lactate to pyruvate in the presence of NAD. The resultant NADH reduces tetrazolium to a red formazan product that is detectable at 490 nm by a microplate reader (Sunrise, Tecan). The reference wavelength was 620 nm. LDH activity was calculated according to the standard curve as U/L.

3.6. Cell viability assay

Cell viability was determined using the Alumar blue assay (16). Briefly, cells were plated at a density of 1×104 cells/well in 96-well plates and incubated overnight, and were then treated for 24 h with either vehicle or various concentrations of Sanggenon C (2, 10, 25, 50, 100 microM). At the end of the experiment, cells were stained with 10% Amalur blue solution for 4 h, and the plate was read in a microplate reader at 570/600 nm (VERSAmax; Molecular Devices). Analysis was performed on triplicate wells, and the data presented is representative of three independent experiments.

3.7. Cell death assay

Cell death was quantified using an AnnexinV-FITC/PI kit and FACSCalibur flow cytometry as described previously (17). Cells were plated at a density of 2×105 cells per well in six-well plates and incubated overnight, and were then treated with either vehicle or Sanggenon C as indicated. After treatment with Sanggenon C, cells were collected, washed with PBS, resuspended in 500 microliter of binding buffer and incubated with 1 microgram/ml Annexin V-FITC and 2 microgram/ml PI for 10 min in the dark, and then flow cytometric analysis was performed within 1 h. At least a total of 10,000 cells were acquired per sample, and data were analyzed using CellQuest software (BD PharMingen). Cells in the early stages of apoptosis were Annexin V-positive but PI-negative, whereas cells in the late stages of apoptosis were both Annexin V- and PI-positive.

3.8. Cell cycle analysis

Cell cycle analysis was performed as reported previously (18). H22 or P388 cells were seeded in 6-cm dishes overnight in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, then treated with 20 microM Sanggenon C at indicated time points. The cells were collected by centrifugation at 100 g for 5 min, washed by PBS, stained with PI in the presence of RNAase. Data was analyzed based on the distribution of cell populations in different phases of cell cycle.

3.9. Western blot analysis

Cells were seeded in 6-cm diameter dishes and incubated overnight, and were then either treated with vehicle or Sanggenon C as indicated. After treatment, cells were washed twice with cold PBS and solubilized in lysis buffer. Protein samples (20–60 microgram) were separated by SDS/PAGE (12% gels) and transferred on to a PVDF (Amersham Biosciences). The membrane was incubated with anti-ubiquitin, anti-p27, anti-PARP or anti-GAPDH as primary antibodies which were diluted in 5% non-fat milk in PBS with 0.1% Tween 20, followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated IgG (Amersham Biosciences) as the secondary antibody. The secondary antibodies on the PVDF membrane were detected using the enhanced chemiluminescnce (ECL) detection reagents (Amersham Bioscience) and exposed to X-ray films(NY14608, Kodak) (19).

4. RESULTS

4.1. Determination of Sanggenon C Structure

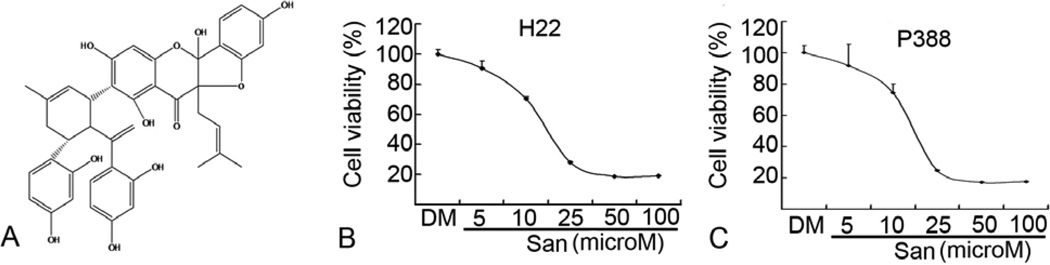

We first determined the structure of purified Sanggenon C we isolated. All the properties, including light yellow powder (MeOH); UV (CHCl3) lamdamax (logEpsilon) 306 (3.67), 280 (3.93), 230 (4.75), 220 (5.35) nm; IR (KBr) vmax 3370 (-OH), 1630 (s, C=O), 1261, 840, 796 cm−1; ESI-MS m/z 707.8 [M + H]+; 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectral data (Table 1) were the same as the reported literature (20) and therefore, the molecular structure of our isolated compound was elucidated as Sanggenon C (Figure 1A).

Table 1.

1H (500 MHz) and 13C (125 MHz) NMR spectral data (DMSO–d6) for Sanggenon C

| Positions | deltaH (J in Hz) | deltaC mult | Positions | deltaH (J in Hz) | deltaC mult |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 90.6 | 14 | 4.08 ~ 4.24 (1H) | 33.8 | |

| 3 | 102.4 | 15 | 5.231 (1H) | 122.2 | |

| 4 | 187.4 | 16 | 133.1 | ||

| 4a | 99.0 | 17 | 1.728 (3H, s) | 23.9 | |

| 5 | 163.9 | 18 | 2.101 ~ 2.405 (2H) | 31.8 | |

| 6 | 108.1 | 19 | 3.87 ~ 4.08 (1H) | 33.8 | |

| 7 | 168.1 | 20 | 4.487 (1H) | 47.8 | |

| 8 | 5.623 (1H, s) | 95.0 | 21 | 206.8 | |

| 8a | 160.5 | 22 | 114.6 | ||

| 1’ | 123.2 | 23 | 164.6 | ||

| 2’ | 160.2 | 24 | 6.084 (1H, d, J = 2) | 103.4 | |

| 3’ | 6.224 (1H, d, J =2) | 98.9 | 25 | 164.9 | |

| 4’ | 160.4 | 26 | 6.321 (1H, dd, J = 2, 8) | 106.6 | |

| 5’ | 6.387 (1H, dd, J =2, 8.8) | 109.3 | 27 | 8.165 (1H, d, J = 8) | 129.3 |

| 6’ | 7.238 (1H, d, J =8.4) | 125.5 | 28 | 120.2 | |

| 9 | 2.659 (1H, dd, J =9, 14) 3.024 (1H, dd, J =9, 14) |

30.6 | 29 | 156.1 | |

| 10 | 5.121 (1H, m) | 118.2 | 30 | 6.105 (1H, d, J = 2) | 102.8 |

| 11 | C11-CH3 1.472, 1.521 (each 3H, s) | 135.8 | 31 | 156.4 | |

| 12 | 26.1 | 32 | 5.938 (1H, dd, J = 2, 7.6) | 108.0 | |

| 13 | 18.4 | 33 | 6.875 (1H, d, J = 8.4) | 133.2 |

Figure 1.

Sanggeon C inhibits cell proliferation of H22 and P388 cell lines in a dose-dependent manner. Elucidation of the molecular structure of Sanggenon C as shown in (A). H22 (B) or P388 (C) cells were plated in 96-well plate (4000 cells each well) and treated with different concentrations of Sanggenon C for 24 h, followed by Alamur blue assay. The mean value of IC50 was calculated on three independent experiments. In all the 3 cell lines, the IC50 was around 15 microM.

4.2. Cytotoxicity of Sanggenon C in murine hepatoma H22 and leukemic P388 cells

Flavonoids from Chinese Morus Mongolia were reported to show higher cytotoxicity against human oral tumor cell lines (HSC-2 and HSG) than against normal human gingival fibroblasts (HGF). Among the flavonoids in Morus Mongolia, the Diels-Alder type flavanone Sanggenon C was the most potent (13). In the current study, the inhibitory effect of Sanggenon C on cell proliferation was first evaluated by Alamur blue assay in two murine cancer lines: hepatoma H22 and leukemic P388 cells. Results of Alumar blue assay showed that Sanggenon C inhibited cell proliferation in these tumor cells with the IC50 value of ~15 microM (Figure 1B and C). Since cell viability was dependent upon either cell cycle arrest and/or cell death, next we determined the effect of Sanggenon C on both cell cycle arrest and cell death.

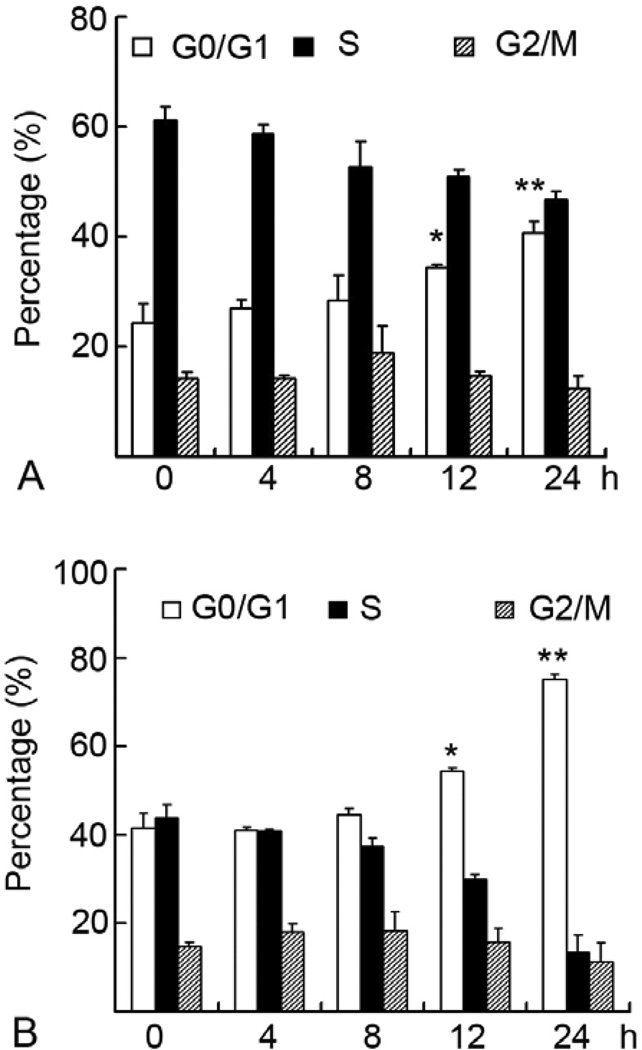

4.3. Sanggenon C induces cell cycle arrest at G0/G1 phase in H22 and P388 cells

Cell cycle analysis was performed by flow cytometry. P388 (Figure 2A) or H22 (Figure 2B) cells were treated with 20 microM Sanggenon C for 4, 8, 12, and 24 h, followed by flow cytometry. The cells in G0/G1 phase in untreated H22 cells (0 h) are around 40%, which was increased to 80% after 24h treatment with Sanggenon C (Figure 2B). Furthermore, Sanggenon C-induced G0/G1 increase is time-dependent. The percentage of G2 phase cells remained relatively unchanged while S phase cell population decreased in a time-dependent manner after Sanggenon C treatment (Figure 2A–B). Consistent to H22 cells, P388 cells showed the same tendency (Figure 2A). In untreated P388 cells (0 h), G0/G1 phase cells are about 20% and reach as high as 40% after Sanggenon C treatment for 24 h. Sanggenon C-induced accumulation of G0/G1 phase cells was accompanied with the decrease of S phase in P388 cells (Figure 2A). These data clearly show that Sanggenon C induces cell cycle arrest at G0/G1 phase and blocked the cell transition at the G1/S boundary.

Figure 2.

Sanggeon C induces cell cycle arrest at G0/G1 phase in H22 and P388 cells. H22 and P388 cells were exposed to 20 microM Sanggenon C for indicated hours, followed by PI staining and detected with a flow cytometer. Cell cycle was analyzed by cycle software. A summary of cell cycle data in P388 cells (A) and H22 cells (B) was shown.

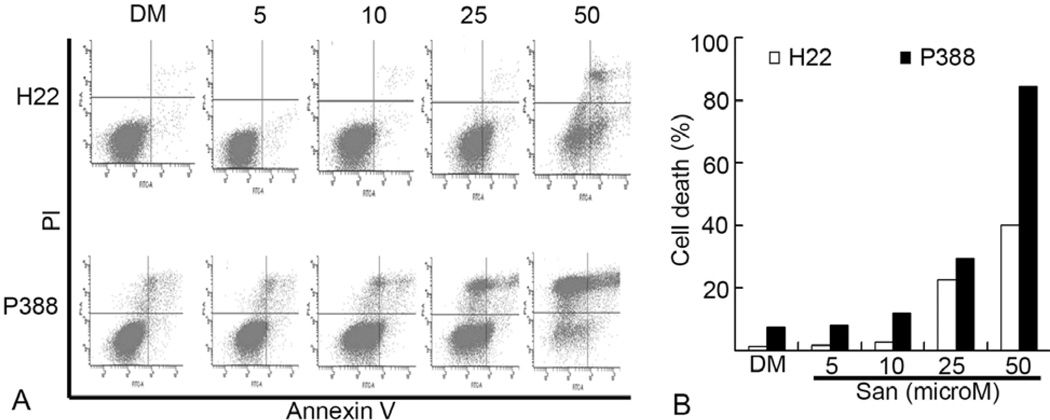

4.4. Sanggenon C causes cell death in H22 and P388 cells

We also measured cell death in H22 and P388 cells after Sanggenon C treatment by using Annexin V-Propidium iodide (PI) double staining, followed by flow cytometry analysis. As shown in Figure 3, compared to the vehicle DMSO treatment, Sanggenon C at higher than 25 microM induced marked cell death in both H22 and P388 cell lines, and P388 cells were more sensitive to Sanggenon C-induced cell death than H22 cells. The P388 cell death induced by 50 microM of Sanggenon C is around 80%, while H22 cell death is around 40% under the same condition. The typical cleaved PARP fragment p85/PARP reflecting cellular apoptosis was also detected after 6 h treatment with 50 microM Sanggenon C in both H22 (Figure 4C) and P388 cells (Figure 4D). Therefore, Sanggenon C is able to induce cell death in these murine cancer cells.

Figure 3.

Dose effects of Sanggeon C on the induction of cell death in murine hepatoma H22 and leukemic P388 cells.. (A) Dosage effect of cell death induction in H22 cells (upper) and P388 cells (lower). Murine hepatoma H22 and P388 cells were treated with various doses of Sanggenon C for 6 h and cell death was detected with Annexin V-PI staining assay by flow cytometry. The lower right part (Annexin V-FITC + / PI −) was considered as early stage of apoptotic cells and upper right part (Annexin V-FITC + / PI +) was considered late stage of apoptotic cells. The upper left part (Annexin V-FITC + / PI +) was considered as necrosis. Typical flow images were shown in A and a summary of cell death was in B.

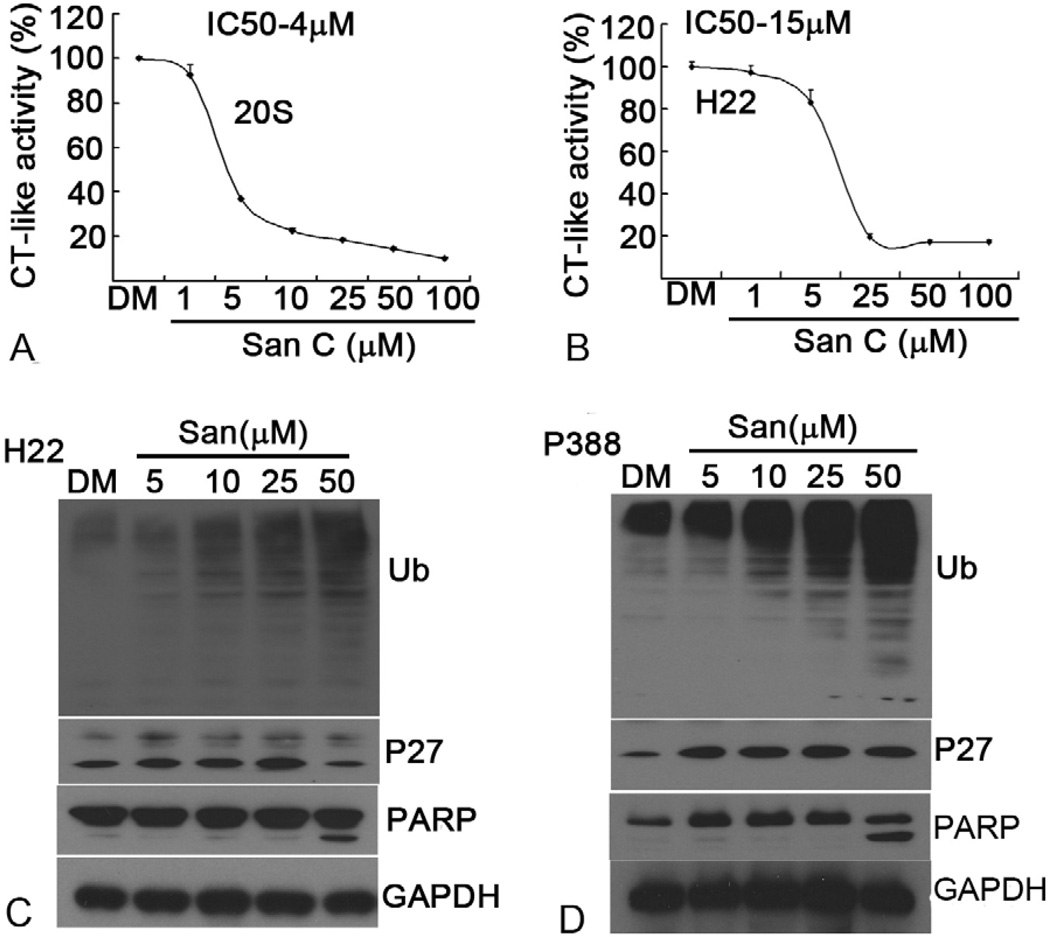

Figure 4.

Sanggenon C inhibits proteasome activity in vitro and in cultured H22 and P388 cells. (A and B) Inhibition of chymotrypsin-like activity by Sanggenon C. Purifed human 20S proteasome or H22 cell lysate (10 microgram protein) was treated with different doses of Sanggenon C for 90 mins and chymotrypsin-like activity was detected by a fluorescence plate reader. The IC50 values of Sanggenon C were 4 microM, 15 microM each for 20S proteasome and H22 cell lysate. (C and D) Does effect on proteasome inhibition and PARP cleavage. Murine H22 cells (C) and P388 cells (D) were separately treated with either solvent DMSO (DM) or indicated concentrations of Sanggenon C for 6 h, followed by Western blotting analysis using specific antibodies against ubiquitinated proteins (Ub), p27 and PARP. Molecular weight of p27 is 27 kDa,. Full length PARP is 116 kDa, and the cleaved fragment of PARP is 85 kDa. GAPDH was used as a loading control.

4.5. Sanggenon C inhibits the chymotrypsin-like activity of a purified human 20S proteasome and 26S proteasome in H22 cell lysate

Above data strongly supported that natural product Sanggenon C decreases cancer cell viability by inducing both cell cycle arrest and cell death, but the involved mechanism needs to be further clarified. Since Sanggenon C contains an aromatic ketone structure that has been shown to be involved in proteasome inhibition (3, 9), we hypothesize that Sanggenon C decreases cell viability via proteasome inhibition.

It has been shown that inhibition of the proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity is associated with tumor cell death (3, 9, 21). To determine whether Sanggenon C could inhibit the proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity, a cell-free proteasome activity assay was performed. Purified human 20S proteasome or H22 cell lysate (10 microgram protein) containing 26S proteasome was incubated with up to 100 microM Sanggenon C for 90 min in the presence of a specific substrate for proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity. As shown in Figure 4A and B, the chymotrysin-like activity of the purified 20S proteasome and 26S proteasome in H22 cell lysate was significantly inhibited by Sanggenon C with an IC50 values of 4 and 15 microM, respectively. Sanggenon C at 25 microM inhibited more than 80% of the chymotrypsin-like activity of the purified 20S proteasome and 26S proteasome in H22 cell lysate.

4.6. Sanggenon C causes proteasome inhibition in murine H22 and P388 cell lines

To determine whether Sanggenon C can also inhibit the cellular 26S proteasome activity, murine H22 and P388 cells were treated with Sanggenon C at 5, 10, 25 or 50 microM for 6 h, followed by detection of the ubiquitinated protein accumulation in the cells. As shown in Figure 4C and D, ubiquitinated proteins that were tagged by polyubiquitins for the proteasome degradation were accumulated in a Sanggenon C dose-dependent manner: light accumulation by 5 microM Sanggenon C treatment and further accumulation by Sanggenon C at 10–50 microM. We also measured the level of the natural proteasome target protein p27. At relatively low doses of Sanggenon C (5–25 microM), level of p27 expression was dose-dependently increased while at 50 microM p27 was decreased probably due to cell death in H22 cells (Figure 4C). In P388 cells, p27 expression showed the similar tendency as that of poly-ubiquitinated proteins, even 5 microM of Sanggenon C induced marked accumulation of p27 (Figure 4D).

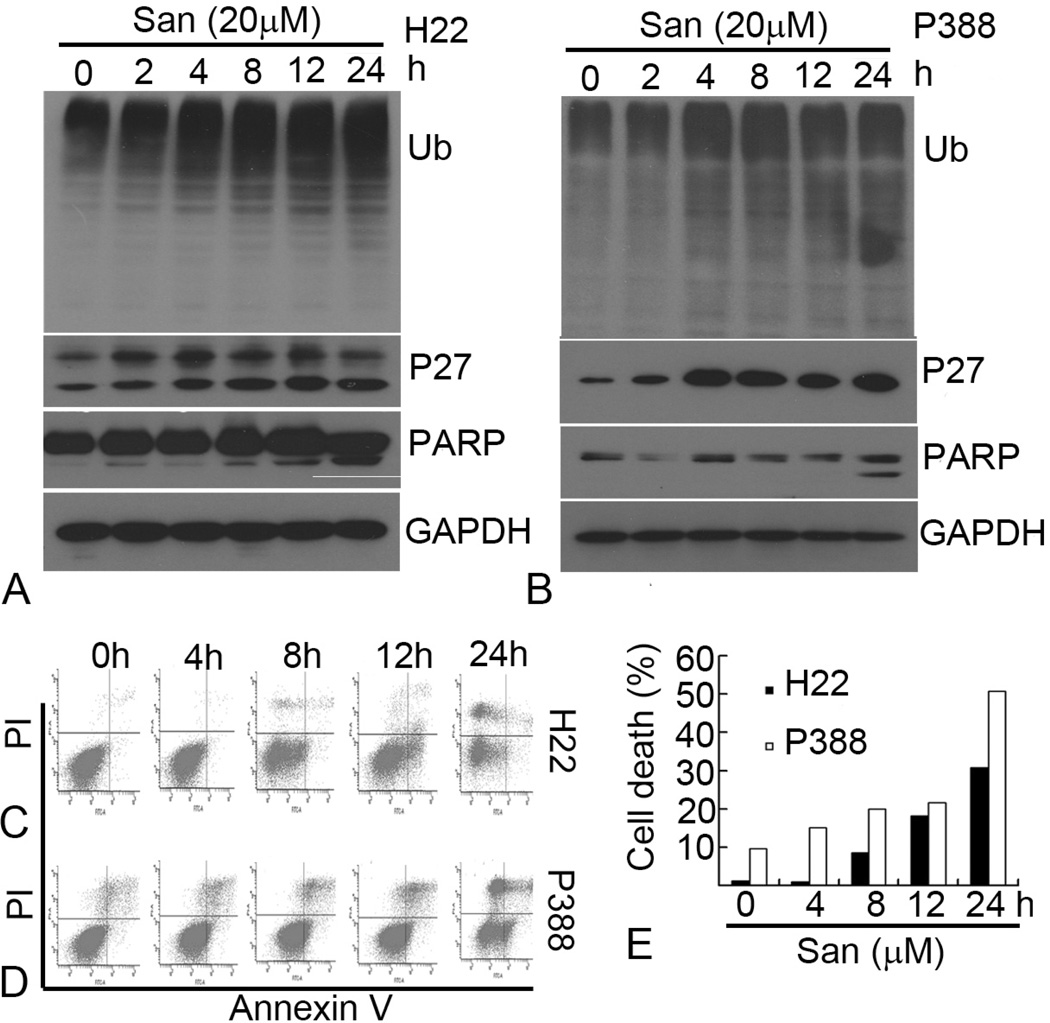

4.7. Sanggenon C-induced tumor cell death occurs after proteasome inhibition

Next we did kinetic experiments using both H22 and P388 cells to determine which event occurs first, proteasome inhibition or cell death induction. H22 and P388 cells were treated with 20 microM Sanggenon C for up to 24 h, followed by Western blotting and flow cytometry analysis. As shown in Figure 5A and B, the levels of ubiquitinated proteins started to increase after 4 h treatment with Sanggenon C. Levels of p27 also started to increase after 2 h treatment (2–8h), but at later points p27 varied because of the protein synthesis/degradation imbalance. In a sharp contrast to the proteasome inhibition at early hours, cell death occurred in later hours. The apparent PARP cleavage, an indicator of apoptotic cell death, was typically detected at 24 h treatment of Sanggenon C in both H22 (Figure 5A) and P388 cell lines (Figure 5B). We further performed flow cytometry to measure the cell death kinetics in H22 and P388 cells after Sanggenon C treatment. In H22 cells cell death started to increase after 8 h treatment (Figure 5C and E) and typical cell death was also observed after 8 h treatment with Sanggenon C in P388 cells (Figure 5D and E).

Figure 5.

Kinetic effects of Sanggeon C on the induction of cell death and proteasome induction in H22 and P388 cells. (A and B) Kinetic effect on proteasome inhibition and PARP cleavage. H22 and P388 cells were treated with 20 microM of Sanggenon C for indicated times, followed by Western blotting analysis using specific antibodies against ubiquitinated proteins (Ub) p27 and PARP. The image is a representative immunoblot from three independent experiments yielding similar results. GAPDH was used as loading control. (C, D, and E) Kinetic effect on cell death induction in H22 and P388 cells. H22 and P388 cells were exposed to 20 microM of Sanggenon C for indicated times, followed by Annexin V-PI staining assay. Typical flow images were shown in (C) and (D). Summary of cell death in H22 and P388 cells was shown in (E).

Taken together, these results indicated that the proteasome inhibition by Sanggenon C was followed by induction of cell death in both cancer cell lines, suggesting that the proteasome is at least one of the cellular targets of Sanggenon C for cell death induction.

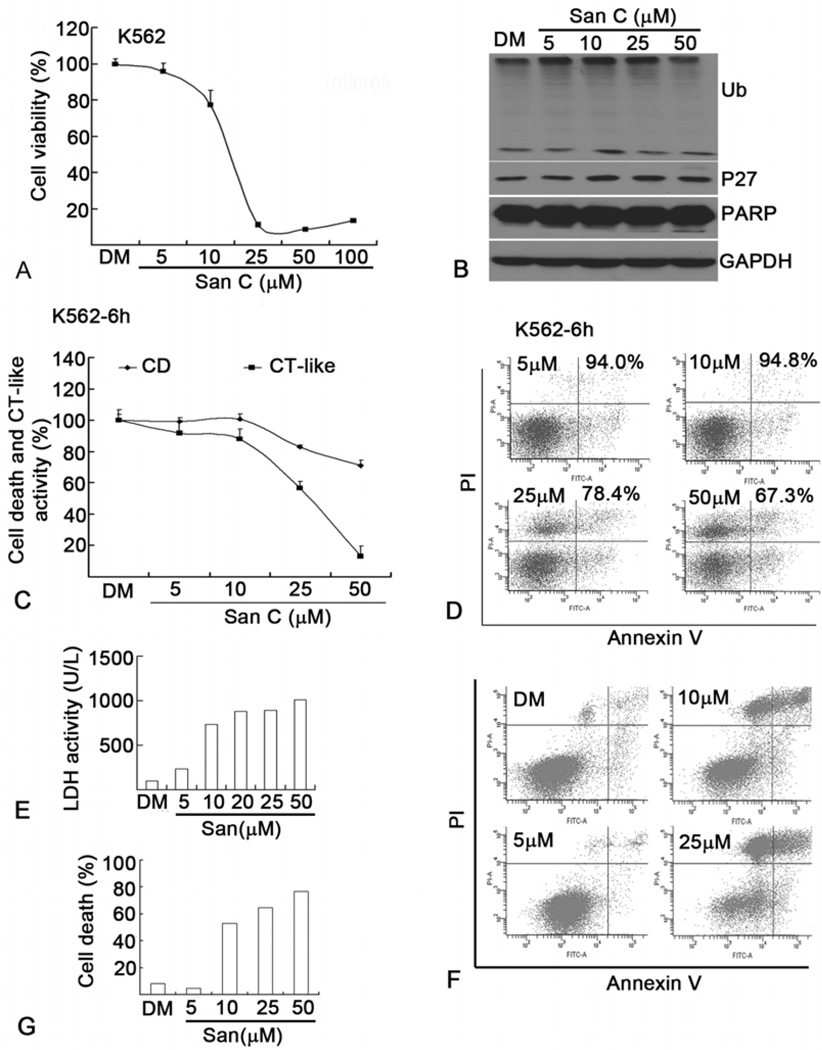

4.8. Sanggenon C decreases cell viability, and induces cell death and proteasome inhibition in human leukemia cells

Since H22 and P388 cells are established murine cancer cell lines, next we determined the effect of Sanggenon C on cell viability, cell death and proteasome inhibition in human leukemia K562 cells and primary leukemic cells from patients with acute leukemia. The IC50 of cell viability in K562 cells was about 15 microM (Figure 6A), similar to H22 and P388 cells (Figure 1B–C). To determine whether Sanggenon C caused proteasome inhibition in K562 cells, levels of ubiquitinated proteins and p27 were detected by Western blotting. As shown in Figure 6B, at relatively low doses Sanggenon C accumulated ubiquitinated proteins and p27 in a dosedependent manner; at 50 microM dose ubiquitinated proteins and p27 did not further increase most likely due to cell death. To confirm Sanggenon C-induced proteasome inhibition in K562 cells, a cell-based proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity was performed in living K562 cells. As shown in Figure 6C, Sanggenon C dose-dependently inhibits the proteasome chymotrypsin-like activity with an IC50 of about 28 microM. Consistent with the idea that proteasome inhibition leads to cell death, cell death was detected only at higher concentrations of Sanggenon C (Figure 6C and D). To further establish the clinical significance of use of Sanggenon C, leukemic cells from patients with leukemia were treated with Sanggenon C. Surprisingly, these primary leukemic cancer cells are even more sensitive to Sanggenon C-induced cell death (Figure 6E–G) than H22 and P388 cells (Figure 3). Sanggenon C at 10 microM induced 50% cell death and high LDH release in primary leukemic cancer cells (Figure 6E–G) while it only induced less than 10% cell death in H22 and P388 cells (Figure 3).

Figure 6.

Sanggenon C induces cell death and proteasome inhibition in human K562 leukemic cells and leukemic cells from patients with leukemia. (A) Dose effect of Sanggenon C on cell viability in human K562 cells. K562 cells were treated as in Figure 1 (B) and (C), cell viability was detected with Alumar blue assay. (B) Dose effect on proteasome inhibition and PARP cleavage. K562 cells were treated with various doses of Sanggenon C for 6 h, followed by Western blotting analysis as shown in Figure 4 (C) and (D). (C) Dose effect on CT-like activities and cell death (CD). K562 cells were plated in 96-well plates or 6-cm dishes and treated with different doses of Sanggenon C for 6 h, followed by in situ chymotrypsin-like assay with Cell-based Chymotrypsin-like assay kit and cell death assay with Annexin V and PI satinning by flow cytometry. (D) Typical cell death images as described in (C) were shown. (E, F and G) Sanggeon C induces cell death in cells from patients with primary T-cell acute lymphocytic leukemia. Human peripheral cells from patients were separated by Ficoll solution and cultured in RPMI-1640 medium with 10% FBS. 36 h later, the cells were plated in either 6-well plates or 6 cm dishes for following experiments. Cells were treated with different doses of Sanggenon C for 8 h, the supernatant was used for LDH release assay and cells were collected for cell death assay by flow cytometry. LDH release as shown in (E), and cell death assay by flow cytometry was shown in (F) and (G).

5. DISCUSSION

Prenylated flavonoids exist widely in plants (24). Sanggenon C is a natural prenylated Diel-Alder adduct of flavanone extracted from Chinese crude drug Shangbaipi (20). One of the cellular molecular targets of Sanggenon C has been suggested to be protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (24), but its biological mechanisms and molecular targets are far from being understood.

In recent years, some novel natural proteasome inhibitors have been found from plants, teas, or Chinese herbs (8, 9). In the reported natural proteasome inhibitors, several flavonoids from plants or foods have been discovered in our lab and other labs. In flavones, chrysin, apigenin and luteolin have been reported to inhibit proteasome function (25, 26); in flavonols, quercetin, myricetin and kaempferol were reported as proteasome inhibitors (3); other flavonoids were also reported as proteasome inhibitors including chalcones and derivatives (27), catechin and derivatives (28), naringenin in flavonones (25) and genistein in isoflavones (29). It has been reported that there are different biological activities between prenylated and non-prenylated flavonoids (30). To our knowledge, natural prenylated flavonoids have never been reported to inhibit proteasome function. This study reveals for the first time that Sanggenon C is a natural proteasome inhibitor and is the first proteasome inhibitor from natural prenylated flavonoids.

We have shown that an aromatic ketone structure may play an important role in interacting with and inhibiting the proteasome (3, 9). Consistently, Sanggenon C with such aromatic ketone structure also acts as a proteasome inhibitor in vitro and in cells as shown in this study. However, whether the chemical structure of prenylation and Diel-Alder adducts in Sanggenon C also affects the proteasome activity is unclear at this moment. It is possible that an unsaturated double bond could be attacked by the N-terminal theronine of the proteasome subunits, leaving to formation of a new covalent bond and resulting in proteasome inhibition. This idea will be tested by computer docking model and experimentally in the near future.

In the current study we have also reported for the first time that Sanggenon C inhibited tumor cell proliferation via induction of cell cycle arrest at G0/G1 phase and induction of cell death. We suggest that Sanggenon C-mediated proteasome is at least partially attributable to induction of cell death and cell growth inhibition. It has been shown that Sanggenon C has the strongest cell toxicity among the flavonoids derived from Chinese Morus Mongolia. Consistent to the previous report (13), we found that Sanggenon C inhibited cell viability in both mouse and human cancer cell lines (H22, K562 and P388) at an IC50 value of about 15 microM. Further experiments found that Sanggenon C induced G0/G1 cell cycle arrest in a time-dependent manner and induced cell death in a dose-dependent manner, which is attributable to the observed decreased cell viability. To our knowledge, this is the first report that Sanggenon C blocks the cell cycle progression at the G1/S boundary.

Proteasome is responsible for the degradation of more than 80% intracellular proteins and therefore is required for the maintenance of cell life. Dysfunction of the ubiquitin proteasome system will lead to various diseases such as cancer (22, 23). Many cell cycle proteins such as CDKs, p27Kip1 and p21, and proapoptotic proteins like Bax are endogenous proteasome substrates which have been chown to regulate cell cycle and cell death (23). Here we found that Sanggenon C induced accumulation of p27 and ubiquitinated proteins in both H22 and P388 cells which contributed to the observed cell cycle arrest and cell death. Consistent with the hypothesis that inhibition of the proteasome causes induction of cell death, in our dose-dependent studies we found that Sanggenon C inhibited the proteasome in both murine and human cancer cells (Figures 4 and 6), which was accompanied by cell death (Figures 3 and 6). Moreover, in our kinetic experiments we found that proteasome inhibition by Sanggenon C occurred before cell death. We detected cell death with multiple assays, all of which showed that cell death occurred after proteasome inhibition (Figure 5), suggesting that proteasome inhibition by Sanggenon C at least partially contributes to the subsequent cell death. It was interesting and exciting to find that primary leukemic cancer cells from leukemic patients are more sensitive than cancer cell lines to Sanggenon C-induced cell death in vitro (Figure 6). This study suggests that Sanggenon C has a great potential to be used clinically for treatment of various human cancers in the future.

However, one of the potential problems we identified was that Sanggenon C mainly induced necrotic cell death in cancer cells which could limit the clinical potential of Sanggenon C. The current results showed that Sanggenon C mainly induced necrotic cell death and partially apoptotic cell death. This conclusion is supported by flow cytometry analysis in all the used cancer cells, Annexin V-positive cells (early and late stage apoptotic cells) were relatively lower than the PI-positive cells (necrotic and late stage apoptotic cells) after Sanggenon C treatment (Figures 3, 5 and 6). Consistently, as shown in Figures 4–6, Sanggenon C did not induce dramatic PARP cleavage, an important marker of apoptosis, and apoptosis is not induced to the similar level of proteasome inhibition under the same experimental conditions. Also in clinical samples in Figure 6E, Sanggenon C induced high LDH release reflecting necrotic cell death. Since some other proteasome inhibitors mainly induced apoptosis (4, 5), while Sanggenon C mainly induced necrotic cell death and partial apoptosis, Sanggenon C-mediated proteasome inhibition may be partially responsible for cell death induced.

In conclusion, Sanggenon C inhibits tumor cell viability via induction of cell cycle arrest and cell death, which is associated with its ability to inhibit the proteasome function and proteasome inhibition by Sanggenon C at least partially contributes to the observed tumor cell growthinhibitory activity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Huang HB, Liu NN and Zhao K contributed equally to this work. This work was supported by The National High Technology Research and Development Program of China 2006AA02Z4B5 (JL), Karmanos Cancer Institute of Wayne State University (QPD), and National Cancer Institute grant 1R01CA120009 and 3R01CA120009-04S1 (QPD).

REFERENCES

- 1.Kim HP, Son KH, Chang HW, Kang SS. Anti-inflammatory plant flavonoids and cellular action mechanisms. J Pharmacol Sci. 2004;96:229–245. doi: 10.1254/jphs.crj04003x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sohn HY, Son KH, Kwon CS, Kwon GS, Kang SS. Antimicrobial and cytotoxic activity of 18 prenylated flavonoids isolated from medicinal plants: Morus alba L., Morus mongolica Schneider, Broussnetia papyrifera (L.) Vent, Sophora flavescens Ait and Echinosophora koreensis Nakai. Phytomedicine. 2004;11:666–672. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen D, Daniel KG, Chen MS, Kuhn DJ, Landis-Piwowar KR, Dou QP. Dietary flavonoids as proteasome inhibitors and apoptosis inducers in human leukemia cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;69:1421–1432. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anan A, Baskin-Bey ES, Bronk SF, Werneburg NW, Shah VH, Gores GJ. Proteasome inhibition induces hepatic stellate cell apoptosis. Hepatology. 2006;43:335–344. doi: 10.1002/hep.21036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamamoto Y, Gaynor RB. Therapeutic potential of inhibition of the NF-kappaB pathway in the treatment of inflammation and cancer. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:135–142. doi: 10.1172/JCI11914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pye J, Ardeshirpour F, McCain A, Bellinger DA, Merricks E, Adams J, Elliott PJ, Pien C, Fischer TH, Baldwin AS, Jr, Nichols TC. Proteasome inhibition ablates activation of NF-κB in myocardial reperfusion and reduces reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H919–H926. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00851.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Depre C, Wang Q, Yan L, Hedhli N, Peter P, Chen L, Hong C, Hittinger L, Ghaleh B, Sadoshima J, Vatner DE, Vatner SF, Madura K. Activation of the cardiac proteasome during pressure overload promotes ventricular hypertrophy. Circulation. 2006;114:1821–1828. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.637827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang H, Zonder JA, Dou QP. Clinical development of novel proteasome inhibitors for cancer treatment. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;18:957–971. doi: 10.1517/13543780903002074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang H, Chen D, Cui QC, Yuan X, Dou QP. Celastrol, a triterpene extracted from the Chinese "Thunder of God Vine," is a potent proteasome inhibitor and suppresses human prostate cancer growth in nude mice. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4758–4765. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Groll M, Ditzel L, Lowe J, Stock D, Bochtler M, Bartunik HD, Huber R. Structure of 20S proteasome from yeast at 2.4 A resolution. Nature. 1997;386:463–471. doi: 10.1038/386463a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li LC, Shen F, Hou Q, Cheng GF. Inhibitory effect and mechanism of action of sanggenon C on human polymorphonuclear leukocyte adhesion to human synovial cells. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2002;23:138–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cui L, Na M, Oh H, Bae EY, Jeong DG, Ryu SE, Kim S, Kim BY, Oh WK, Ahn JS. Protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B inhibitors from Morus root bark. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16:1426–1429. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.11.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi YQ, Fukai T, Sakagami H, Chang WJ, Yang PQ, Wang FP, Nomura T. Cytotoxic flavonoids with isoprenoid groups from Morus mongolica. J Nat Prod. 2001;64:181–188. doi: 10.1021/np000317c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu J, Zheng H, Tang M, Ryu YC, Wang X. A therapeutic dose of doxorubicin activates ubiquitin-proteasome system-mediated proteolysis by acting on both the ubiquitination apparatus and proteasome. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H2541–H2550. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01052.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang H, Zhang X, Li S, Liu N, Lian W, McDowell E, Zhou P, 1, Zhao C, Guo H, Zhang C, Yang C, Wen G, Dong X, Lu L, Ma N, Dong W, Dou QP, Wang X, Liu J. Physiological levels of ATP Negatively Regulate Proteasome Function. Cell Res. 2010;20:1372–1385. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakayama GR, Caton MC, Nova MP, Parandoosh Z. Assessment of the Alamar Blue assay for cellular growth and viability in vitro. J Immunol Methods. 1997;204:205–208. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(97)00043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang H, Zhou P, Huang H, Chen D, Ma N, Cui QC, Shen S, Dong W, Zhang X, Lian W, Wang X, Dou QP, Liu J. Shikonin exerts antitumor activity via proteasome inhibition and cell death induction in vitro and in vivo. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:2450–2459. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ormerod MG. Investigating the relationship between the cell cycle and apoptosis using flow cytometry. J Immunol Methods. 2002;265:73–80. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(02)00071-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu J, Chen Q, Huang W, Horak KM, Zheng H, Mestril R, Wang X. Impairment of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in desminopathy mouse hearts. Faseb J. 2006;20:362–364. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4869fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nomura T, Fukai T, Hano Y. Structure of sanggenon C, a natural hypotensive diels-alder adduct from Chinese crude drug "SANG-BAI-PI" (morus root barks) Heterocycles. 1981;16:2141–2148. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drexler HC. Activation of the cell death program by inhibition of proteasome function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:855–860. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.3.855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldberg AL. Protein degradation and protection against misfolded or damaged proteins. Nature. 2003;426:895–899. doi: 10.1038/nature02263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway: on protein death and cell life. Embo J. 1998;17:7151–7160. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.24.7151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee NK, Son KH, Chang HW, Kang SS, Park H, Heo MY, Kim HP. Prenylated flavonoids as tyrosinase inhibitors. Arch Pharm Res. 2004;27:1132–1135. doi: 10.1007/BF02975118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen D, Chen MS, Cui QC, Yang H, Dou QP. Structure-proteasome-inhibitory activity relationships of dietary flavonoids in human cancer cells. Front Biosci. 2007;12:1935–1945. doi: 10.2741/2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen D, Landis-Piwowar KR, Chen MS, Dou QP. Inhibition of proteasome activity by the dietary flavonoid apigenin is associated with growth inhibition in cultured breast cancer cells and xenografts. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:R80. doi: 10.1186/bcr1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Achanta G, Modzelewska A, Feng L, Khan SR, Huang P. A boronic-chalcone derivative exhibits potent anticancer activity through inhibition of the proteasome. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:426–433. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.021311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nam S, Smith DM, Dou QP. Ester bond-containing tea polyphenols potently inhibit proteasome activity in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:13322–13330. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004209200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kazi A, Daniel KG, Smith DM, Kumar NB, Dou QP. Inhibition of the proteasome activity, a novel mechanism associated with the tumor cell apoptosis-inducing ability of genistein. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66:965–976. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00414-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodriguez RJ, Miranda CL, Stevens JF, Deinzer ML, Buhler DR. Influence of prenylated and non-prenylated flavonoids on liver microsomal lipid peroxidation and oxidative injury in rat hepatocytes. Food Chem Toxicol. 2001;39:437–445. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(00)00159-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]