Abstract

Taxpayers' willingness to cooperate with the state and its institutions in general, and their willingness to pay taxes in particular, depend on a variety of variables. While economists stress the relevance of external variables such as tax rate, income and probability of audits and severity of fines, psychological research shows that internal variables are of similar importance. We present a comprehensive review on the relevance of citizens' knowledge of tax law, their attitudes towards the government and taxation, personal norms, perceived social norms and fairness, as well as motivational tendencies to comply, and discuss possibilities for strategic intervention to increase tax compliance.

Keywords: tax behavior, tax compliance, norms, attitudes, fairness

Citizens' inclination to cooperate with the state and its institutions in general, and their willingness to pay taxes in particular, depend on a variety of variables. While economists stress the relevance of external variables such as tax rate, income and probability of audits and severity of fines, psychological research shows that internal variables are of similar importance: taxpayers' knowledge of tax law, their attitudes towards the government and taxation, personal norms, perceived social norms and fairness, as well as motivational tendencies to comply are psychological determinants shaping tax behavior (Kirchler, 2007).

Empirical research on determinants of tax behavior has shown mixed evidence on the specific weight of economic variables: some studies found audits and fines to increase compliance, other studies have not found any or even opposite effects (Fischer, Wartick & Mark, 1992; Andreoni, Erard & Feinstein, 1998). The inconsistency of patterns of results suggests that economic and psychological determinants operate differently under different circumstances. Kirchler, Hölzl and Wahl (2008) developed a model suggesting that audits and fines are relevant under the condition of low trust in governmental institutions and tax authorities in particular, especially if the government has the power to exert audits effectively. In a climate of mutual distrust, citizens can be forced to comply. On the other hand, if the climate is characterized by mutual trust, audits and fines would signal authoritarianism and distrust, and thus, rather than increasing compliance, be ineffective or even counterproductive. In a climate of mutual trust, citizens have positive representations of the tax systems and tax authorities and cooperate spontaneously. High subjective tax knowledge, favorable attitudes, personal and social norms of cooperation, as well as perceived fairness of the tax system are the basis of a motivational tendency to cooperate, of trust, and of voluntary compliance.

We present a comprehensive review of psychological research on (a) knowledge and evaluation of taxation, including the structure of knowledge and attitudes towards taxation, (b) personal and social norms, (c) fairness perceptions, and (d) motivational postures and discuss their impact on willingness to cooperate and spontaneously comply with the law. Implications for tax authorities are elaborated in the final section.

1. Knowledge and evaluation of taxation

An essential factor influencing tax compliance is the knowledge of taxation. Tax law is complex due to high levels of abstraction and technical terms (McKerchar, 2001). To comprehend the tax law in Britain, it was estimated that at least 13 years of education are required; reading age in the U.S. was calculated to be 12.5 years of schooling, whereas in Australia estimations rose to 17 years. Most people do not have more than 9 to 10 years of school education (Lewis, 1982). Unsurprisingly, the majority of taxpayers does not understand tax law correctly, and thus, complain about having poor subjective knowledge (e.g., Roberts, Hite & Bradley, 1994; Schmölders, 1960) and feeling incompetent concerning tax issues (Sakurai & Braithwaite, 2003). Empirical evidence shows that poor knowledge on the tax system breeds distrust (Niemirowski, Wearing, Baldwin, Leonard & Mobbs, 2002).

People not only have difficulties to understand tax law, they also show poor knowledge about tax rates and basic concepts of taxation. For example, British citizens underestimated tax rate by about 11% when asked for actual tax rates for various income brackets (Lewis, 1978). Surveys on people's acceptance of flat and progressive tax showed different preferences depending on the mere manner of presentation: If income and tax were presented in absolute amounts, respondents preferred flat tax; if income and tax share were presented in percentages, respondents preferred progressive tax (Roberts et al., 1994). Poor knowledge can evoke distrust and negative attitudes towards tax, whereas good tax knowledge correlates with positive attitudes towards tax (Niemirowski et al., 2002).

Studies on knowledge and evaluation have addressed people's understanding and acceptance of tax phenomena as well as relevant associations towards taxation held by different groups of taxpayers. While from the perspective of the community, tax avoidance, tax evasion, and tax flight all have similar negative consequences, people evaluate these phenomena differently. Formally, tax avoidance is defined as the legal reduction of income and/or the legal increase of expenditures by a creative design of the tax statement (Webley, 2004), tax evasion is a deliberately illegal act to reduce tax burden (Elffers, Weigel & Hessing, 1987), and tax flight means taxpayers' legal relocation of their domiciles and businesses to save taxes (Kirchler, Maciejovsky & Schneider, 2003). In a qualitative study (Kirchler et al., 2003) participants related tax avoidance to lawful acts enabling tax reduction, to cleverness, and to costs. Tax evasion was associated with illegal acts (e.g., fraud), criminal prosecution, risk, tax-audits, punishment, penalty, and the risk of detection. Tax flight was associated with the idea of saving taxes, the feeling that taxes are considerably lower abroad, and costs of relocation. In general, tax avoidance was perceived as legal and moral, tax evasion was related to illegal behavior and immorality, while tax flight was perceived as legal but also as immoral.

Taxes mostly are perceived as a burden. However, the burden originates from different sources of citizens' perceived pressure and dissatisfaction. Studies on social representations held by different professional groups in Austria (Kirchler, 1998) and Italy (Berti & Kirchler, 2001) showed that white collar workers perceive taxes as necessary evil that, however, guarantees social welfare and security; blue collar workers mainly accuse the government and politicians of using taxation strategically to enrich themselves; self-employed and entrepreneurs who pay taxes out of their pocket feel taxes to limit their personal freedom to invest hard earned money in their own business (Kirchler, 1998).

In general, tax avoidance is accepted instead of being perceived as harm to the community. Tax evasion is not judged as a severe economic crime. In Austria (Kirchler, 1998) and Italy (Berti & Kirchler, 2001), studies on the evaluation of “typical” taxpayers, honest taxpayers, and tax evaders revealed that tax evaders are evaluated rather positively, “typical” taxpayers most negatively and honest taxpayers most positively. Tax evaders are described as the most intelligent and hard working. The perception of tax evasion as an intelligent performance but not a serious crime is a general phenomenon in tax research. In early studies (Schmölders, 1960, 1964), about half of the respondents described tax evaders as cunning businessmen. Compared to other offences, tax evasion is evaluated as less severe than drunk driving or stealing a car; it is perceived just a bit more serious than stealing a bike (Song & Yarbrough, 1978; Vogel, 1974). There are theoretical assumptions that these attitudes towards tax evasion can be partly explained by Christian values which demand for hard work and modesty, and ascribe prosperity to hard work. Not declaring earned money and keeping the tax share, rather than being judged as a crime, might be classified as the just compensation for hard work (Lamnek, Olbrich & Schaefer, 2000).

Subjective knowledge and attitudes, in our case towards taxation, form the bases of behavioral intentions (Ajzen, 1985; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). Based on the above presented research, we assume that detailed knowledge and favorable attitudes contribute to trust in authorities and consequently to voluntary tax compliance.

2. Norms

People develop ethical standards of adequate conduct in a society and are aware of social norms that regulate behavior in a society. Research on tax behavior has addressed ethical standards as personal norms, social norms, and societal norms (Wenzel, 2004).

Personal norms comprise personality factors, moral reasoning, values, religious beliefs, etc. In general, empirical studies show that the personality factor Machiavellianism furthers tax evasion (Adams & Webley, 2001; Kirchler & Berger, 1998; Webley, Cole & Eidjar, 2001), while altruistic orientation and community values advance tax compliance (Blamey & Braithwaite, 1997; Braithwaite, 2003a). Honesty as a strong personal value (Porcano, 1988) as well as religious beliefs (Grasmick, Bursik & Cochran, 1991; Stack & Kposowa, 2006; Torgler, 2003b, 2006) have a positive empirical effect on tax compliance. Tax compliance is also related to political affiliation: people favoring parties with social democratic values tend to comply more than people voting for liberal parties (Wahlund, 1992). Finally, taxpayers with strong values for cooperation, who anticipate shame and guilt in case of norm violation, are more compliant than taxpayers who do not anticipate these feelings (Grasmick, Bursik & Cochran, 1991).

Social norms are rooted in socially shared beliefs about how members of a group should behave (Fehr, Fischbacher & Gächter, 2002; Fehr & Gächter, 1998). Individual behavior is regulated by the norms developed and accepted in a society and by approval or disapproval of norm following or norm breaking, respectively (Alm, McClelland & Schulze, 1999). With regard to tax behavior, a field experiment reveals that social norms regulating compliance base on perceived frequency of avoidance or evasion and societal acceptance of evasion (Wenzel, 2005a). Other studies fond that communication about correct tax behavior and disapproval of non-compliance lead to tax honesty (Alm, McClelland & Schulze, 1999; Trivedi, Shehata & Lynn, 2003; Wenzel, 2005b). Sigala, Burgoyne and Webley (1999) found that social norms are one of the most important predictors of tax compliance. Depending on perceived evasion in one's reference group, such as professional groups, friends and acquaintances, and acceptance of evasion, taxpayers comply to tax law or develop a more lenient tax behavior (e.g., Porcano, 1988; Welch, Xu, Bjarnason & O'Donnell, 2005), and perceive tax evasion as minor crime (Welch et al., 2005). These results suggest that normative appeals to comply may be of high relevance to increase tax compliance within a society (Schwartz & Orleans, 1967; Spicer & Lundstedt, 1976).

The relation between strong social norms to comply and actual compliance is mediated by people's attachment to their reference group or the society (Wenzel, 2004). This empirical finding is in line with self-categorization theory (Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher & Wetherell, 1987) which assumes that individuals are more likely to be influenced by the norms established by their group if they consider the group to which they belong as highly relevant for their self image and if they identify with their group. Communication of social norms held by the citizens, stressing the importance of correct tax filing as a civic duty, effectively shapes tax compliance.

Societal norms of tax behavior are reflected partly in tax laws, and partly in tax morale and civic duty. Tax morale is defined as the aggregated attitudes of a group or population to comply with tax law (Schmölders, 1960). Tax morale is linked to the motivational concept of civic duty: individuals are not solely motivated by maximization of their own wellbeing but also by a sentiment of responsibility to society (Orviska & Hudson, 2002). People with a high sense of civic duty comply with tax law because of their intrinsic motivation, not because they are forced by sanctions and audits (Frey & Eichenberger, 2002). Results on tax behavior in different countries highlight the importance of societal norms. Experimental studies with the identical paradigm found that tax compliance was higher in the U.S. than in Spain (Alm, Sanchez & deJuan, 1995). Other studies confirm national differences (Alm, Martinez-Vazquez & Schneider, 2004; Alm & Torgler, 2006; Chan, Troutman & O'Bryan, 2000; Gërxhani, 2004; Gërxhani & Schram, 2006; Schneider, 2004; Torgler, 2003a; Torgler & Schneider, 2007).

3. Fairness

Perceived fairness of taxation has been found to be covarying strongly with compliance. On the one hand, perceived fairness determines tax compliance (Andreoni et al., 1998; Kirchler, 2007). On the other hand, talk about unfairness serves rationalization and justification of tax non-compliance (Falkinger, 1988).

Fairness is related to the perceived balance of taxes paid and public goods received, and to the perceived justice of procedures and consequences of norm breaking. Wenzel (2003) extensively discusses various types of fairness (distributive justice, procedural justice, and retributive justice) in the context of tax behavior. Summary descriptions are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Distributive justice, procedural justice and retributive justice by individual, group and societal level (Wenzel, 2003, p. 49ff)

| Level of analysis | Societal level | Group level | Individual level |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Distributive justice in tax research | |||

| Tax burdens | tax level; distribution; progressivity |

in-group's tax burden; compared to other groups; other times; its relative income |

personal tax burden; compared to others; other times; one's relative income |

| Tax based benefits | level of spending; efficiency; distribution over different policies |

in-group's benefits; compared to other groups; other times; its relative income |

personal benefits compared to others; other times; one's relative taxes |

| Avoidance/evasion opportunities |

level; distribution of opportunities |

in-group's options relative to other groups |

personal options compared to others; other times |

|

| |||

| Procedural justice in tax research | |||

|

| |||

| Interactional treatment |

rights for taxpayers and service standards |

respect for the in- group; consistency relative to other groups |

respect for the individual; consistency relative to other individuals |

| Process and decision control |

consultation of taxpayers in general; democratic structures |

voice; control, consultation and representation of in- group |

voice; control; consultation of individual |

| Information and explanation |

transparency; presentation in media |

explanation and justifications for decisions affecting the in-group |

explanations and justifications for decisions affecting the individual |

| Compliance costs | administration and compliance costs; complexity of the tax system |

efficiency; service versus costs for the group |

efficiency; service versus costs for the individual |

|

| |||

| Retributive justice in tax research | |||

|

| |||

| Penalties | severity of penalties; distribution penalties for different offences; quality of penalties |

appropriateness of penalty for in-group (relative to the offence, others) |

appropriateness of penalty for individual (relative to the offence, others) |

| Audits | rigidity or inconsiderateness of audits in general |

rigidity or inconsiderateness of audit for in-group case |

rigidity or inconsiderateness of audit for individual case |

Distributive justice concerns a fair exchange of resources, benefits and costs, and is distinguished into horizontal, vertical and exchange fairness (Kirchler, 2007). Horizontal fairness is related to a fair distribution of benefits and costs within one's income group. Vertical fairness is related to the distribution of benefits and costs across income groups. Finally, exchange fairness is related to taxpayer's tax burden and the provision of public goods by the government. Research on horizontal fairness showed that citizens who feel treated disadvantageously compared to other taxpayers are more likely to evade taxes (e.g., Spicer & Becker, 1980). Citizens who feel that vertical fairness between groups (e.g., rich versus poor people) does not exist tend to evade taxes more than citizens who perceive high vertical fairness (Kinsey & Grasmick, 1993; Roberts & Hite, 1994). Tax evasion is also related to taxpayers' dissatisfaction with the provision of public goods by the government (Spicer & Lundstedt, 1976; see also Alm, Jackson & McKee, 1993; Porcano, 1988; Pommerehne & Frey, 1992).

Procedural justice concerns the process of resource distribution. It was found that procedural justice is high when individuals perceive the rules applied for the distribution of benefits and costs as fair, and treatment by tax authorities as friendly, respectful and supportive (Leventhal, 1980). In line with this, if tax law favored particular income groups relative to others, procedural fairness was perceived as low (Murphy, 2003). Fairness perceptions are enhanced by the provision of information on tax law (Wartick, 1994), as well as by participation in the development of tax law and in decisions on the use of tax revenues (Torgler, 2005). Fair treatment of taxpayers and a culture of mutual understanding between tax authorities and taxpayers improve trust in authorities (Job & Reinhart, 2003; Tyler, 2001; Wenzel, 2006). It was shown that if tax authorities are perceived as supportive, tax compliance increases (Kirchler, Niemirowski & Wearing, 2006).

Retributive justice concerns the perceived fairness of norm-keeping measures, e.g., audit and punishment. Concerning tax behavior, empirical results reveal that high retributive justice prevails when taxpayers agree with governmental tax audits and penalties for tax evasion. Inconsiderate audits and unfair penalties lead to negative attitudes towards tax authorities (Spicer & Lundstedt, 1976). However, universal rules for fairness of penalties are difficult because people take the causes for tax evasion into account when deciding on punishments (Kaplan, Reckers & Reynolds, 1986). Policies and measures used by tax authorities for fiscal reasons can turn out to be detrimental to perceived retributive justice. A highly disputed measure, for example, is tax amnesty. Tax amnesties allow tax evaders to retroactively file their taxes without being punished, leading to higher tax revenue. However, tax amnesties can have negative effects on the compliance of honest taxpayers who feel materially disadvantaged (Hasseldine, 1998; Sausgruber & Winner, 2004).

Although most empirical results support the relation between fairness and tax behavior, some caveats remain. First, the causal relation is unclear. Self-reports of perceived inequity could be stated as ex-post rationalization to justify tax evasion (Falkinger, 1988). Second, moderator variables need to be considered. For example, the empirical effect of perceived justice of one's tax share and participation in public goods on tax behavior is moderated by the importance of equal inputs and outputs (Kim, 2002): distributive justice has a higher relevance for taxpayers who care strongly about receiving public goods equivalent to their tax payments than for other taxpayers. Another empirical tested moderator variable is social and national identity. Tax compliance increases if taxpayers identify with their social category and with their nation, and if they have high feelings of procedural and distributive justice (Wenzel, 2002).

4. Motivational postures

Motivational postures are an aggregation of subjective knowledge and constructs, socially shared beliefs and evaluations of tax issues (Braithwaite, 2003a). They integrate taxpayers' beliefs, evaluations and expectations regarding tax authorities, and also taxpayers' activities deriving from these beliefs, evaluations, and expectations. Thus, they comprise the above discussed topics of knowledge, evaluation, norms, and fairness perceptions. On the group and societal level, motivational postures result in tax morale and civic duty; on the individual level, they guide tax compliance. Braithwaite (2003a) distinguishes five motivational postures: (a) commitment describes a positive orientation towards tax authorities. Committed taxpayers feel a moral obligation to pay their share and to act in the interest of the collective. (b) Capitulation describes acceptance of the tax authorities who hold legitimate power to pursue the collective's goals. Authorities are seen to act in a supportive way as long as citizens act according to the law. (c) Resistance describes a negative orientation and defiance. The authority of tax officers is doubted and their acts are perceived as controlling and dominating rather than as supportive. (d) Disengagement also describes a negative orientation and correlates with resistance. Citizens keep socially distant from authorities and have moved beyond seeing any point in challenging tax authorities. (e) Game playing describes a view of law as something that can be molded to suit one's own purposes rather than as a set of regulations that should be respected as guideline of one's actions. In tax behavior, game playing refers to “cops-and-robbers” games with taxpayers searching loopholes for their advantage and perceiving tax officers as the police who engage in catching cunning taxpayers. While commitment and capitulation describe rather favorable attitudes towards tax authorities, resistance, disengagement, and game playing reflect a negative orientation towards tax authorities.

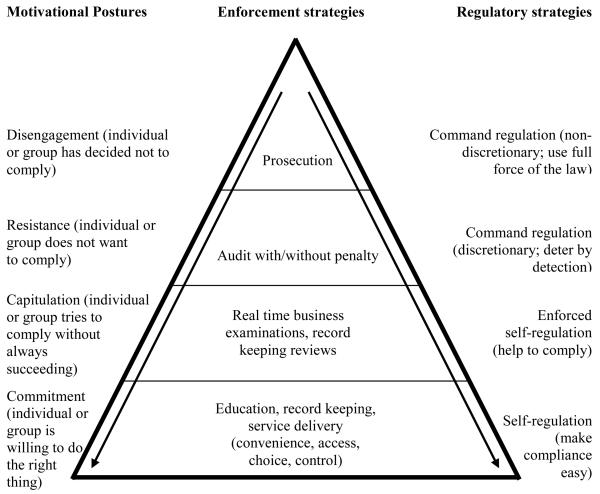

Empirical research on motivational postures showed that they can change over time and that different postures can be held simultaneously (Braithwaite, 2003a). As situations, such e.g. the early answer to a request of the tax authorities to pay the annual income tax, change also taxpayers' sentiments and therefore motivational postures tend to change. Motivational postures need to be considered by governments to understand taxpayers' sentiments, and can be used to increase tax compliance. The Australian Taxation Office compliance model (Braithwaite, 2003b) pictures how tax authorities appropriately should respond to each motivational posture; it is depicted in Figure 1. For four motivational postures it offers enforcement strategies ranging from prosecution to education and service delivery, and additionally suggests adequate regulatory strategies ranging from command-regulation to self-regulation. For example, tax evasion conducted in a motivational posture of commitment should be answered with education, record-keeping and service. The idea is that tax evasion was an unintentional error, and self-regulation would be an efficient strategy. On the other extreme, tax evasion conducted in a motivational posture of disengagement should be answered with prosecution, and with a strategy of command regulation.

Figure 1.

Australian Taxation Office Compliance Model adapted from Braithwaite (2003b, p. 3) and James, Hasseldine, Hite and Toumi (2003)

5. Conclusion and implications

The present review shows that taxpayers' willingness to cooperate is not only influenced by audits and fines, but also by a number of internal variables. We argue that many of these variables can be understood as contributing to trust in the tax authorities. In particular, we discussed the relevance of knowledge and evaluation of taxation, of norms, of fairness and of motivational postures. In the following section, we develop some suggestions for tax compliance programs building on the above reviewed research.

Some tax compliance programs simply focus on the accomplishment of more audits and severe punishment, but tax research supports a multifaceted approach (Alm & Torgler, 2006). Such an approach includes consideration of audits and punishment and additionally of concepts to improve taxpayers' knowledge of tax law, to form more positive attitudes towards tax issues, and to enhance fairness perceptions. There are different ways for tax authorities to realize such programs.

Programs should aim at improving taxpayers' knowledge on tax law. Findings that more than average schooling is necessary to understand tax law (Lewis, 1982) and that the help of tax practitioners is required to file taxes (Blumenthal & Christian, 2004) show that it is essential to simplify tax law. John Braithwaite (2005) argues for a complete reformation of the law, and proposes to integrate specific rules into principles to avoid the following negative dynamics: “[a] smorgasbord of rules engenders a cat-and-mouse legal drafting culture – of loophole closing and reopening by creative compliance” (p. 147). The prescription of overarching principles that serve to clearly guide behaviour would prevent many such “games”. For common transactions and for very complex areas of tax law, rules should be formulated; however, if a rule is in contest with an overarching principle, the principle is binding.

It is also necessary to provide understandable arguments for specific changes of the tax law. For example, people seem to have difficulties understanding flat and progressive tax systems (Roberts et al., 1994). Communication programs should consist of different schemes on societal, group and individual levels. On the group level, brochures and courses on tax law for specific groups (e.g., free lancers, families, etc.) can improve tax knowledge in those areas that are particularly relevant for a specific group of taxpayers. On the individual level, “open house” events where tax officers advise taxpayers free of charge on their tax statements can improve taxpayers' knowledge of taxes important to them. Additionally, they would build mutual trust between taxpayers and tax officers and improve attitudes towards tax authorities.

Programs should also focus on the structure of knowledge and attitudes, because the facts that taxes are viewed as a burden and as money lost (Kirchler, 1998), that tax evasion is viewed as a minor crime (Song & Yarbrough, 1978; Vogel, 1974), and that tax evaders are viewed as intelligent (Kirchler, 1998), are destructive for tax compliance. Such an attitude is the base for social norms accepting non-compliance. Normative appeals (Spicer & Lundstedt, 1976) can contribute to more positive attitudes. On the societal and the group level, image campaigns to improve attitudes towards tax issues are needed. They could focus on a negative image of tax evasion by presenting the negative effects of lacking government funds, such as a bad school system, broken-down roads, and an insufficient health system, and thus induce feelings of shame and guilt in tax evaders, according to empirical findings (Grasmick et al., 1991) that should lead to more compliant behavior. Based on other research (Job & Reinhart, 2003; Tyler, 2001; Wenzel, 2006), campaigns also should concentrate on the improvement of trust in authorities to enhance citizens' cooperation; they should highlight that tax authorities are service-oriented partners to ensure funding for necessary public goods and to help with correct tax filing. Finally, a campaign to increase identification with the state and to generate a feeling of belonging between taxpayers should be conducted, because, as was shown (Wenzel, 2002), identification increases tax compliance. On the individual level, mutual understanding improves tax compliance (Job & Reinhart, 2003; Tyler, 2001; Wenzel, 2006), that could be achieved by cooperative and personal contact with tax authorities can further. According to empirical findings (Grasmick et al., 1991), the anticipation of shame and guilt if tax evasion is made public, e.g. via media, should also further tax compliance. Moreover, shaming and blaming could be measures to increase restorative fairness rather than punishment – a measure for retributive justice – which might exclude taxpayers from the community and favor further non-cooperation (Kirchler & Mühlbacher, in press; Wenzel & Thielmann, 2006). Nevertheless, taking this measure, authorities have to be aware that ethical questions, such as infringement of data protection, have to be considered.

Programs should also aim at improving fairness perceptions on different levels. Violations of horizontal, vertical and exchange fairness, of procedural fairness and retributive fairness decrease tax compliance (Andreoni et al., 1998; Kirchler, 2007). Conversely, stronger feelings of legitimacy of political institutions lead to higher tax morale and enhance tax compliance (Torgler & Schneider, 2007). Perceptions of fairness and commitment to tax law can be reached with direct democracy (Frey & Eichenberger, 2002; Kirchgässner, Feld & Savioz, 1999), giving taxpayers the possibility to participate in tax law changes and to assign collected taxes to different governmental projects. On an individual level, trust between taxpayers and tax officers should be established, because mutual understanding of each others' goals increases the perception of fairness and therefore also tax compliance (Job & Reinhart, 2003; Tyler, 2001; Wenzel, 2006).. Training for tax officers that concentrates on respectful treatment of taxpayers can support the development of the relationship (James & Alley, 2002). Respectful treatment would include that tax officers would see it as their task to advise taxpayers and to perceive taxpayers as cooperative individuals and not as savvy citizens searching for loopholes to escape the law.

In conclusion, external measures to reduce tax avoidance, such as audits and fines, may be effective if tax authorities and taxpayers perceive each other as competing parties. If tax authorities and taxpayers should, however, perceive each other as cooperating and pursuing similar community goals, internal variables are more important in shaping taxpayers' willingness to cooperate (Kirchler, Hölzl & Wahl, 2008). Variables such as taxpayers' knowledge of tax law, their attitudes towards the government and taxation, personal norms, perceived social norms and fairness, as well as motivational tendencies to comply are psychological determinants leading to and underlying voluntary compliance, whereas effective audits and fines may guarantee enforced compliance, and bear the risk to destroy existing voluntary compliance.

Acknowledgements

This paper was partly funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), P19925-G11.

References

- Adams C, Webley P. Small business owners' attitudes on VAT compliance in the UK. Journal of Economic Psychology. 2001;22(2):195–216. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In: Kuhl J, Beckmann J, editors. Action-Control: From Cognition to Behavior. Springer; Heidelberg: 1985. pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Alm J, Torgler B. Culture differences and tax morale in the United States and in Europe. Journal of Economic Psychology. 2006;27(2):224–246. [Google Scholar]

- Alm J, Jackson BR, McKee M. Fiscal exchange, collective decision institutions, and tax compliance. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. 1993;22(3):285–303. [Google Scholar]

- Alm J, Martinez-Vazquez J, Schneider F. “Sizing” the problem of the hard-to tax. In: Alm J, Martinez-Vazquez J, Wallace S, editors. Taxing the hard-to-tax. Lessons from theory and practice. Elsevier; Amsterdam, NL: 2004. pp. 11–75. [Google Scholar]

- Alm J, McClelland GH, Schulze WD. Changing the social norm of tax compliance by voting. Kyklos. 1999;52(2):141–171. [Google Scholar]

- Alm J, Sanchez I, deJuan A. Economic and noneconomic factors in tax compliance. Kyklos. 1995;48(1):3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Andreoni J, Erard B, Feinstein JS. Tax compliance. Journal of Economic Literature. 1998;36(2):818–860. [Google Scholar]

- Berti C, Kirchler E. Contributi e contribuenti: Una ricerca sulle rappresentazioni del sistema fiscale. Giornale Italiano di Psicologia. 2001;28(3):595–607. [Google Scholar]

- Blamey R, Braithwaite V. The validity of the security-harmony social values model in the general population. Australian Journal of Psychology. 1997;49(1):71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal M, Christian C. Tax preparers. In: Aaron HH, Selmrod J, editors. The crisis in tax administration. Brookings Institution Press; Washington: 2004. pp. 201–299. [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite J. Markets in vice. Markets in virtue. The Federation Press; Leichhardt, NSW: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite V. Dancing with tax authorities: Motivational postures and non-compliant actions. In: Braithwaite V, editor. Taxing democracy. Understanding tax avoidance and tax evasion. Ashgate; Aldershot, UK: 2003a. pp. 15–39. [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite V. A new approach to tax compliance. In: Braithwaite V, editor. Taxing democracy. Understanding tax avoidance and tax evasion. Ashgate; Aldershot, UK: 2003b. pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Chan CW, Troutman CS, O'Bryan D. An expanded model of taxpayer compliance: Empirical evidence from the United States and Hong Kong. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing & Taxation. 2000;9(2):83–103. [Google Scholar]

- Elffers H, Weigel RH, Hessing DJ. The consequences of different strategies for measuring tax evasion behaviour. Journal of Economic Psychology. 1987;8(3):311–337. [Google Scholar]

- Falkinger J. Tax evasion and equity: A theoretical analysis. Public Finance. 1988;43(3):388–395. [Google Scholar]

- Fehr E, Gächter S. Reciprocity and economics. The economic implications of homo reciprocans. European Economic Review. 1998;42(3-5):845–859. [Google Scholar]

- Fehr E, Fischbacher U, Gächter S. Strong reciprocity, human cooperation, and the enforcement of social norms. Human Nature. 2002;13(1):1–25. doi: 10.1007/s12110-002-1012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer CM, Wartick M, Mark MM. Detection probability and taxpayer compliance: A review of the literature. Journal of Accounting Literature. 1992;11(1):1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior. Addison Wesley; Reading: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Frey BS, Eichenberger R. Democratic governance for a globalized world. Kyklos. 2002;55(2):265–288. [Google Scholar]

- Gërxhani K. Tax evasion in transition: Outcome of an institutional clash? Testing Feige's conjecture in Albania. European Economic Review. 2004;48(4):729–745. [Google Scholar]

- Gërxhani K, Schram A. Tax evasion and income source: A comparative experimental study. Journal of Economic Psychology. 2006;27(3):402–422. [Google Scholar]

- Grasmick HG, Bursik RJ, Cochran JK. “Render unto Caesar what is Caesar's”: Religiosity and taxpayers' inclinations to cheat. The Sociological Quarterly. 1991;32(2):251–266. [Google Scholar]

- Hasseldine JD. Tax amnesties: An international review. Bulletin for International Fiscal Documentation. 1998;52(7):303–310. [Google Scholar]

- James S, Alley C. Tax compliance, self-assessment and tax administration. Journal of Finance and Management in Public Services. 2002;2(2):27–42. [Google Scholar]

- James S, Hasseldine JD, Hite PA, Toumi M. Tax compliance policy: An international comparison and new evidence on normative appeals and auditing; Paper presented at the ESRC Future Governance Workshop; Vienna, Austria: Institute for Advanced Studies; Dec, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Job J, Reinhart M. Trusting the tax office: Does Putnam's thesis relate to tax? Australian Journal of Social Issues. 2003;38(3):307–334. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan SE, Reckers PMJ, Reynolds KD. An application of attribution and equity theories to tax evasion behavior. Journal of Economic Psychology. 1986;7(4):461–476. [Google Scholar]

- Kim CK. Does fairness matter in tax reporting behavior? Journal of Economic Psychology. 2002;23(6):771–785. [Google Scholar]

- Kinsey KA, Grasmick HG. Did the tax reform act of 1986 improve compliance? Three studies of pre- and post-TRA compliance attitudes. Law & Policy. 1993;15(4):239–325. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchgässner G, Feld LP, Savioz MR. Die direkte Demokratie. Vahlen; München, D: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchler E, Mühlbacher S. Leitner R, editor. Kontrollen und Sanktionen im Steuerstrafrecht aus der Sicht der Rechtspsychologie. Finanzstrafrecht 2007. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchler E. Differential representations of taxes: Analysis of free associations and judgments of five employment groups. Journal of Socio-Economics. 1998;27(1):117–131. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchler E. The economic psychology of tax behaviour. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchler E, Berger MM. Macht die Gelegenheit den Dieb? Jahrbuch für Absatz- und Konsumentenforschung. 1998;44:439–462. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchler E, Hölzl E, Wahl I. Enforced versus voluntary tax compliance: The “slippery slope” framework. Journal of Economic Psychology. 2008;29(2):210–255. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchler E, Maciejovsky B, Schneider F. Everyday representations of tax avoidance, tax evasion, and tax flight: Do legal differences matter? Journal of Economic Psychology. 2003;24(4):535–553. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchler E, Niemirowski P, Wearing A. Shared subjective views, intent to cooperate and tax compliance: Similarities between Australian taxpayers and tax officers. Journal of Economic Psychology. 2006;27(4):502–517. [Google Scholar]

- Lamnek S, Olbrich G, Schaefer W. Tatort Sozialstaat: Schwarzarbeit, Leistungsmissbrauch, Steuerhinterziehung und ihre (Hinter)Gruende. Leske + Budrich; Opladen: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal GS. What should be done with equity theory? New approaches to the study of fairness in social relationships. In: Gergen KJ, Greenberg MS, Willis RH, editors. Social exchange. Plenum; New York, NY: 1980. pp. 27–55. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis A. Perception of tax rates. British Tax Review. 1978;6:358–366. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis A. The psychology of taxation. Martin Robertson; Oxford: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- McKerchar M. ATAX Discussion Paper. University of Sydney; Orange, Australia: 2001. The study of income tax complexity and unintentional noncompliance: Research method and preliminary findings. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy K. Procedural justice and tax compliance. Australian Journal of Social Issues. 2003;38(3):379–407. [Google Scholar]

- Niemirowski P, Wearing AJ, Baldwin S, Leonard B, Mobbs C. The influence of tax related behaviours, beliefs, attitudes and values on Australian taxpayer compliance. Is tax avoidance intentional and how serious an offence is it? University of New South Wales; Sydney: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Orviska M, Hudson J. Tax evasion, civic duty and the law abiding citizen. European Journal of Political Economy. 2002;19(1):83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Pommerehne W, Frey BS. The effects of tax administration on tax morale. Universität Konstanz; Juristische Fakultät: 1992. (No. Serie II, Nr. 191). [Google Scholar]

- Porcano TM. Correlates of tax evasion. Journal of Economic Psychology. 1988;9(1):47–67. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts ML, Hite PA. Progressive taxation, fairness and compliance. Law & Policy. 1994;16(January):27–47. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts ML, Hite PA, Bradley CF. Understanding attitudes toward progressive taxation. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1994;58(2):165–190. [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai Y, Braithwaite V. Taxpayers' perceptions of practitioners: Finding one who is effective and does the right thing? Journal of Business Ethics. 2003;46(4):375–387. [Google Scholar]

- Sausgruber R, Winner H. Steueramnestie abgesagt: Eine kluge Entscheidung? Empirische Evidenz aus OECD-Ländern. Österreichische Steuerzeitung. 2004 May 15;10/2004:207–211. [Google Scholar]

- Schmölders G. Das Irrationale in der öffentlichen Finanzwirtschaft. Suhrkamp; Frankfurt am Main, D: 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Schmölders G. Finanzwissenschaft und Finanzpolitik. J. c. B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck); Tübingen, D: 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider F. Shadow economics around the world: What do we really know? European Journal of Political Economy. 2004;21(3):598–642. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz R, Orleans S. On legal sanctions. University of Chicago Law Review. 1967;34(Winter):274–300. [Google Scholar]

- Sigala M, Burgoyne C, Webley P. Tax communication and social influence: Evidence from a British sample. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology. 1999;9(3):237–241. [Google Scholar]

- Song Y-D, Yarbrough TE. Tax ethics and taxpayer attitudes: A survey. Public Administration Review. 1978;38(5):442–452. [Google Scholar]

- Spicer MW, Becker LA. Fiscal inequity and tax evasion: An experimental approach. National Tax Journal. 1980;33(2):171–175. [Google Scholar]

- Spicer MW, Lundstedt SB. Understanding tax evasion. Public Finance. 1976;21(2):295–305. [Google Scholar]

- Stack S, Kposowa A. The effect of religiosity on tax fraud acceptability: A cross-national analysis. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2006;45(3):325–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5906.2011.01568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torgler B. Tax morale in transition countries. Post-Communist Economies. 2003a;15(3):357–381. [Google Scholar]

- Torgler B. Tax morale, rule-governed behaviour and trust. Constitutional Political Economy. 2003b;14(2):119–140. [Google Scholar]

- Torgler B. Tax morale and direct democracy. European Journal of Political Economy. 2005;21(2):525–531. [Google Scholar]

- Torgler B. The importance of faith: Tax morale and religiosity. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization. 2006;61(1):81–109. [Google Scholar]

- Torgler B, Schneider F. What shapes attitudes toward paying taxes? Evidence from multicultural European countries. Social Science Quarterly. 2007;88(2):443–470. [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi VU, Shehata M, Lynn B. Impact of personal and situational factors on taxpayer compliance: An experimental analysis. Journal of Business Ethics. 2003;47(3):175–197. [Google Scholar]

- Turner JC, Hogg M, Oakes PJ, Reicher SD, Wetherell MS. Rediscovering the social group. A self-categorization theory. Blackwell; Oxford, UK: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler TR. Public trust and confidence in legal authorities: What do majority and minority group members want from the law and legal institutions? Behavioral Sciences and the Law. 2001;19(2):215–235. doi: 10.1002/bsl.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel J. Taxation and public opinion in Sweden: An interpretation of recent survey data. National Tax Journal. 1974;27(1):499–513. [Google Scholar]

- Wahlund R. Tax changes and economic behavior: The case of tax evasion. Journal of Economic Psychology. 1992;13(4):657–677. [Google Scholar]

- Wartick M. Legislative justification and the perceived fairness of tax law changes: A reference cognitions theory approach. The Journal of the American Taxation Association. 1994;16(2):106–123. [Google Scholar]

- Webley P. Tax compliance by businesses. In: Sjögren H, Skogh G, editors. New perspectives on economic crime. Edward Elgar; Cheltenham, UK: 2004. pp. 95–126. [Google Scholar]

- Webley P, Cole M, Eidjar O-P. The prediction of self-reported and hypothetical tax-evasion: Evidence from England, France and Norway. Journal of Economic Psychology. 2001;22(2):141–155. [Google Scholar]

- Welch MR, Xu YL, Bjarnason T, O'Donnell P. “But everybody does it…”: the effects of perceptions, moral pressures, and informal sanctions on tax cheating. Sociological Spectrum. 2005;25(1):21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel M. The impact of outcome orientation and justice concerns on tax compliance: The role of taxpayers' identity. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2002;87(4):629–645. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel M. Tax compliance and the psychology of justice: Mapping the field. In: Braithwaite V, editor. Taxing democracy: Understanding tax avoidance and evasion. Ashgate; Hants, UK: 2003. pp. 41–69. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel M. An analysis of norm processes in tax compliance. Journal of Economic Psychology. 2004;25(2):213–228. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel M. Motivation or rationalisation? Causal relations between ethics, norms and tax compliance. Journal of Economic Psychology. 2005a;26(4):491–508. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel M. Misperceptions of social norms about tax compliance: From theory to intervention. Journal of Economic Psychology. 2005b;26(6):862–883. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel M. A letter from the tax office: Compliance effects of informational and interpersonal justice. Social Justice Research. 2006;19(3):345–364. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel M, Thielmann I. Why we punish in the name of justice: Just desert versus value restoration and the role of social identity. Social Justice Research. 2006;19(4):450–470. [Google Scholar]