Abstract

Objectives

This study provides preliminary data and a framework to facilitate cost comparisons for pharmacologic versus behavioral approaches to headache prophylactic treatment.

Background

There are few empirical demonstrations of cumulative costs for pharmacologic and behavioral headache treatments, and there are no direct comparisons of short and long range (5 year) costs for pharmacologic versus behavioral headache treatments.

Methods

Two separate pilot surveys were distributed to a convenience sample of behavioral specialists and physicians identified from the membership of the American Headache Society. Costs of prototypical regimens for Preventive Pharmacologic Treatment (PPT), Clinic-Based Behavioral Treatment (CBBT), Minimal-Contact Behavioral Treatment (MCBT), and Group Behavioral Treatment (GBT) were assessed. Each survey addressed total cost accumulated during treatment (i.e., intake, professional fees) excluding costs of acute medications. The total costs of preventive headache therapy by type of treatment were then evaluated and compared over time.

Results

During the initial months of treatment, PPT with inexpensive mediations (< .75¢/day) represents the least costly regimen and is comparable to MCBT in expense until 6 months. After 6 months, PPT is expected to become more costly, particularly when medication cost exceeds .75¢ a day. When using an expensive medication (>3$/day), preventive drug treatment becomes more expensive than CBBT after the first year. Long term, and within year one, MCBT was found to be the least costly approach to migraine prevention.

Conclusions

Through year 1 of treatment, inexpensive prophylactic medications (such as generically available beta-blocker or tricyclic antidepressant medications) and behavioral interventions utilizing limited delivery formats (minimal-contact behavior treatment) are the least costly of the empirically validated interventions. This analysis suggests that, relative to pharmacologic options, limited format behavioral interventions are cost competitive in the early phases of treatment and become more cost efficient as the years of treatment accrue.

Keywords: migraine, headache, cost, behavioral

Introduction

A wide range of effective preventive pharmacologic1-5 and behavioral headache treatments are available to headache sufferers.6-10 Behavioral headache treatments (i.e., relaxation training, biofeedback, cognitive-behavioral therapy, stress-management training) represent an effective treatment option that is essentially free of side effects, while providing durable treatment gains over time.6-10 There is a sizeable amount of evidence indicating that, at least among those patients who respond initially, the effects of behavioral treatments endure over time, with the longest follow-up occurring seven years post-treatment.11-14 For example, Blanchard and colleagues13 reported that 91% of migraine headache sufferers remained significantly improved five years after completing behavioral headache treatment. Furthermore, these benefits endure whether or not further contact (i.e., booster treatment sessions) is provided.14 Meta-analyses demonstrate that the efficacy of behavioral treatment is on par with empirically validated medications for migraine prophylaxis.7,8,15-18 Ideally, the choice of headache treatment would be guided by efficacy research as well as by objective cost-benefit analysis. In practice, viability of treatment is probably influenced by immediate costs as well as efficacy of available treatments. Unfortunately, there are few systematic studies of headache treatment costs to help inform treatment decisions.

Preliminary efforts have been made to evaluate the cost and cost-effectiveness of pharmacologic treatments.19-24 Attempts to evaluate the cost of behavioral interventions for headache have suggested that the standard clinic-based behavioral interventions may be costly, although none have systematically looked at cost over time or compared them to pharmacologic costs.7-8 There is, however, some evidence that behavioral treatment can reduce subsequent medical costs.25

The present study projects direct costs that accrue over time with the pharmacologic versus behavioral preventive treatments of headache. The present study utilizes what Kernick26 has labeled a cost minimization analysis. Perhaps the simplest form of pharmacoeconomic evaluation, a cost minimization analysis assumes outcomes to be equivalent and thus compares only the costs of equivalent treatments. Using this approach, the direct costs associated with several preventive therapies can be directly compared under a variety of situations and treatment approaches.

Methods

Preventive Treatment Modalities

Direct costs of the following preventive treatment modalities were calculated. A brief description of each modality is provided below:

Clinic Based Behavioral Treatment (CBBT)

Behavior headache therapy or cognitive behavioral therapy traditionally is administered in 8 to 12 weekly therapist-administered individual clinic sessions, conducted in an office setting.7-8 Such interventions include: biofeedback, progressive muscle relaxation training, hypnosis, cognitive therapy, stress management skills, problem solving interventions, and other time-limited psychological therapies.

Minimal Contact Behavioral Treatment (MCBT)

In a minimal-contact or “home-based” intervention, self-regulation skills are introduced in the clinic, but training primarily occurs at home with the patient guided in part by printed materials and audio recordings.7-8 Consequently, direct therapist-patient contact is limited to only three or four clinic sessions rather than the eight or more weekly clinic sessions required for the standard clinic-based format.

Group Behavior Treatment (GBT)

In clinical practice, behavioral interventions for headache often are administered in small groups (rather than individually). Where patient flow is adequate, group administration rather than individual treatment sessions allows the cost of treatment to be reduced and professional time to be efficiently allocated.

Preventive Pharmacologic Treatment (PPT)

Effective prophylactic headache medications are available at a range of price points.1-5 Because of the wide-ranging options available, each with unique dose ranges and different associated costs, only a total daily cost associated with a potential regimen is considered in this analysis. Because of the rapidly changing nature of pharmaceutical costs (ie, changes in patent protections), it is intended that this more general cost/day approach will allow for a comparison that is more broadly applicable and durable than analysis of specific medications that would be relevant only at the time of publication. For a general list of monthly costs associated with common medications used for preventive headache treatment, the interested reader is referred to Adelman and colleagues.13

Procedure

As the subject of this investigation was the costs of therapy (i.e., not human subjects data), the approval of a human subjects review board was judged unnecessary for conducting this work (the Institutional Review Board at the University of Mississippi Medical Center confirmed this opinion). Physicians and behavioral headache specialists known to the authors were identified among the membership of the American Headache Society to form a convenience sample. To obtain information about the behavioral treatments, a survey was distributed via email to the Behavioral Issues Group of the American Headache Society in May of 2006. The survey requested information about the average number of treatment sessions and the professional fees for intake assessments and treatment sessions for each behavioral treatment modality. A similar approach was undertaken at the same time for the pharmacologic treatments. Physicians known by the investigators to treat a substantial headache patient population were surveyed about the direct costs associated with the various headache preventive treatments for the average headache patient. Clinicians estimated the number of clinic visits required for the average headache patient as well as professional fees for intake assessments and medication management visits. No attempts were made to inquire about the physicians prescribing practices. Participants were assured anonymity.

Direct costs of pharmacologic and behavioral preventive treatments were calculated from practitioner surveys of professional fees. In addition to professional fees, the total cost of preventive pharmacotherapy was calculated by adding the cost of professional fees to daily medication costs ranging from $0.50/day to $6/day. No attempt was made to factor in the cost of acute medications since acute relief medications would be used by patients receiving either behavioral therapy or prophylactic medication.

Statistical Analysis

Survey data were collected and entered into SPSS for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). Descriptive statistics (ie., range, median, mean, and mode) were calculated for each aspect of the calculation. Direct cost/month was then calculated for each modality with particular costs outlined below. For sake of comparison, separate calculations were conducted for the lowest, highest, and median monthly cost.

Results

Sixteen surveys of behavioral treatment and 8 surveys of pharmacologic treatment were completed and returned. Psychologists comprised 100% of the behavioral treatment respondents and neurologists comprised 75% of the PPT respondents while the remaining were internal medicine and family practice physicians. These doctors ranged from 17 to 34 years in practice with a median of 22.5 years. Respondents reported treating a range of 15% to 100% of their patients for headache (median 87%) and all reported prescribing preventive drug treatment for headache.

Typical number of sessions, costs of intake sessions, and professional fees of CBBT, MCBT, and GBT varied among the different modalities. CBBT was delivered with a median of 10 sessions (range: 6 to 12 sessions), with median prices ranging from $70 to $250 for an intake session and $65 to $200 for a follow-up or treatment session professional fee. The median values for the intake session and professional fee were $175 and $125 respectively. MCBT was delivered with a median of 4 sessions (no variability in range), with intake sessions ranging from $165 to $175 with a median of $170, while the professional fee had a median (no range) of $135. GBT was delivered with a median of 8 sessions (range: 5 to 8 sessions), with intake sessions ranging from $165 to $200 with a median of $175. The professional fee for GBT was the least costly, with a median of $82.50 and a range of $75 to $90.

The various costs of PPT were estimated from five factors: intake session cost, professional fee cost, time to first follow up, time to second follow up, and number of visits each year thereafter. The median cost of an intake session was $250 with a range of $150 to $600. The professional fee costs were a median of $140/session with a range of $75 to $216. The median time to first follow-up was 52.5 days with a range of 30 to 90 days. After that, the median time to second follow-up was 60 days, ranging from 30 to 90 days. These times with subsequent follow-ups resulted in 5 median number of visits/year ranging from 3 to 6 visits each year.

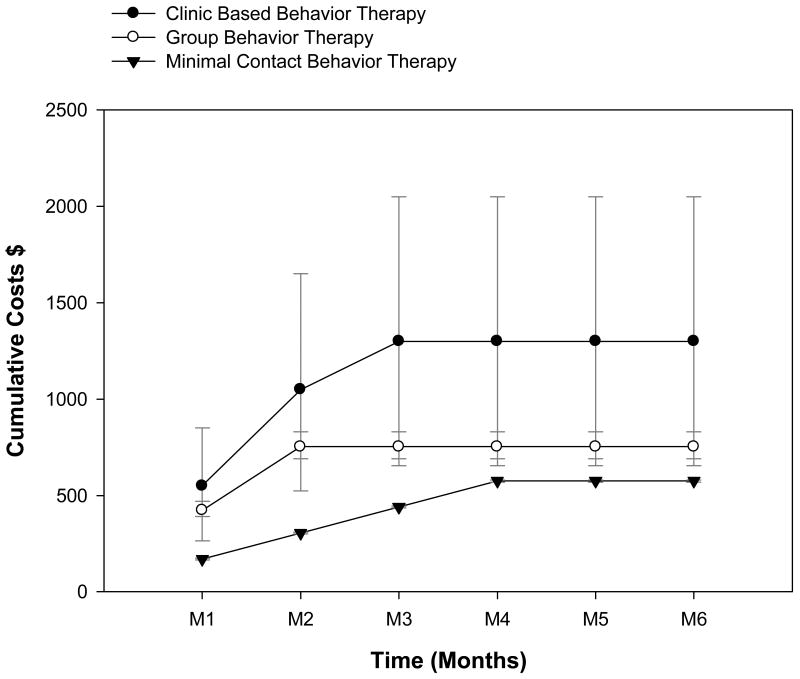

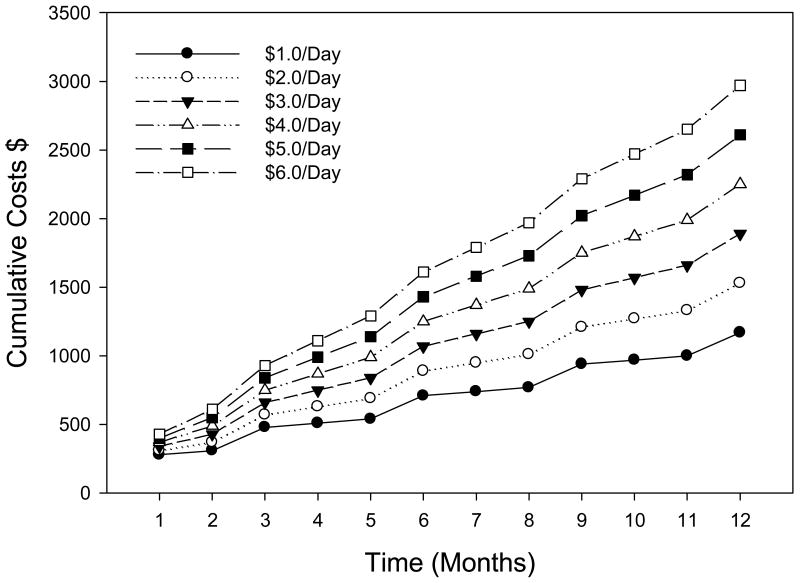

Figure 1 plots cumulative cost of behavioral treatments over six months. The CBBT and GBT both reach maximum cumulative median costs of $1300 and $752 during the third month of treatment. Cumulative costs of MCBT increase more gradually and stabilize at $575 during month four. Figure 2 plots the cumulative cost data for the PPT treatment over one year for various medication prices, ranging from $1/day to $6/day. The cumulative costs of PPT continue to grow over time. Cumulative costs for the most expensive PPT considered (i.e., $6/day) is $1610 at month 6 and is $2970 at year 1. Using $1/day medication, these same intervals show prices of $710 at 6 months and $1170 at the end of one year.

Figure 1.

Comparison of cumulative monthly cost for clinic based behavior therapy (CBBT; 10 total sessions), group behavior therapy (GBT; 8 total sessions), and minimal contact behavior therapy (MCBT; 4 total sessions) over the course of 6 months.

Figure 2.

Total cost of preventive pharmacologic treatment, including medication costs ($1 - $6/Day) intake fee ($250), and 4 additional clinic visits each year ($140 professional fee for each), over the course of 12 months.

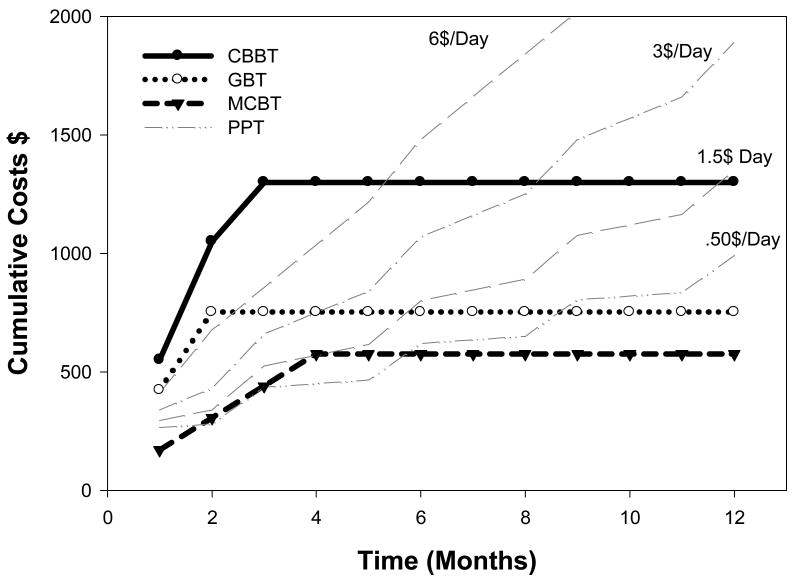

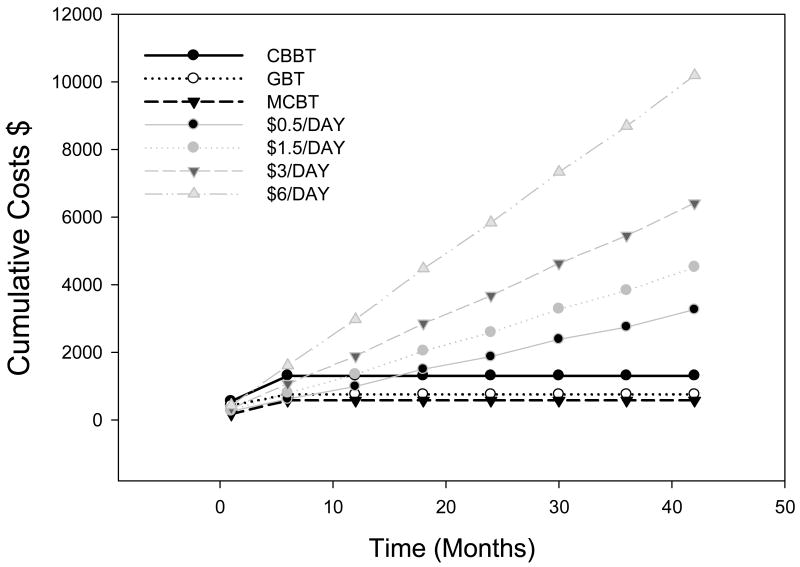

A comparison of cumulative costs for the four treatment modalities is displayed during the first year in Figure 3 and the first 3.5 years in Figure 4 (3.5 years was selected as physician respondents estimated this time as the median amount of PPT treatment duration for their typical patient). PPT using the most expensive medications considered ($6/day) is initially more expensive than either MCBT or GBT and becomes more costly than CBBT during month 5. The least expensive medication considered, at $0.50/day, is cost competitive with MCBT and GBT until month 9, and this form of PPT continues to be less expensive than CBBT until month 18. PPT using a modestly-low priced medication ($1.50/day) surpasses MCBT in price at month 4, while a slightly more expensive PPT ($3/day) is more expensive during even the first month.

Figure 3.

One-year cumulative cost comparison between clinic based behavior therapy (CBBT), group behavior therapy (GBT), and minimal contact behavior therapy (MCBT) and total cost of preventive drug therapy ($0.50, $1.50, $3, and $6/Day).

Figure 4.

Three and one-half year cost comparison between clinic based behavior therapy (CBBT), group behavior therapy (GBT), and minimal contact behavior therapy (MCBT) and total cost of preventive drug therapy ($0.50, $1.50, $3, and $6/Day).

Discussion

Using a cost minimization analysis to quantify the direct costs associated with various preventive headache treatments, this study demonstrates that the financial costs of headache treatments vary considerably. This comparison suggests that traditional CBBT is the most costly of the behavioral treatment modalities and is more costly than pharmacologic treatment during the initial months of treatment. However, CBBT becomes cost competitive with medications within 6 months of treatment and less costly than all but the least expensive generically available medications after approximately 1 year. MCBT and GBT are cost competitive with even the most inexpensive prophylactic medications within the initial months of treatment, and at 1 year they become the least expensive headache treatment choice. These data suggest that behavioral interventions, particularly MCBT and GBT, are less costly than pharmacologic interventions over time. This conclusion is supported further by the fact that our obtained estimates of yearly preventive medication costs were actually lower than those derived from a recent Markov decision analytic modeling study (in which yearly cost of PPT for migraine ranged from $2932 to $3887).27

A future, more sophisticated, comparison could index the costs and benefits associated with these various treatments. Such a traditional cost-benefit analysis would involve the very difficult task of translating outcomes of all considered modalities into a similar metric, and in equating the groups of patients who may have been selected to receive a particular treatment based on a pre-existing need (e.g., a depressive disorder, personality disorder, etc.). Because the cost minimization analysis assumes equivalent outcomes, and in turn equivalence across patient samples, subsequent studies should attend to issues of patient selection and equivalence regarding factors such as headache frequency, rates of medication overuse, and comorbid disorders, Similar cost-benefit analyses could focus more broadly on comparisons of associated facility costs, patient perceptions of treatment safety, and outcomes that extend beyond symptom reduction (i.e., quality of life, improved functioning).28

Conversely, the combination of pharmacotherapy and behavioral interventions can be more effective than either alone,29 but at the present time it is unclear if the combined approach is associated with cost savings. It is conceivable that the self-management strategies encouraged by the behavioral approaches might lead to reduced medical costs in the long-term. In clinical practice, the vast majority of patients receive only PPT, and there may be unique costs associated with one or both approaches that were not well covered by the present analysis (e.g., an adverse event incurred during a PPT trial that required additional diagnostic testing). Future studies could examine the role of combined therapies in reducing these rare but costly events.

Though cost is only one factor to be considered in planning treatment, it is often a primary determinant of services for patients and practitioners alike,30,31 and efficacy alone is insufficient for informing decisions pertaining to health care policy and practice. While behavioral interventions for headache have been well-validated empirically and have garnered increasing acceptance in recent years, these therapeutic modalities are not widely integrated into the clinical management of headache patients. Broadscale integration into mainstream healthcare practice depends greatly upon more systematically addressing access as well as financial and reimbursement barriers associated with this valuable approach to care.

Acknowledgments

Supported by: NIH/NINDS R01NS065257

Abbreviations

- PPT

preventive pharmacologic treatment

- MCBT

minimal contact behavioral treatment

- CBBT

clinic based behavioral treatment

- GBT

group behavioral treatment

Contributor Information

Allison M. Schafer, Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine, Blacksburg, VA, USA.

Jeanetta C. Rains, Center for Sleep Evaluation, Elliot Hospital, Manchester, NH, USA.

Donald B. Penzien, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS, USA.

Leanne Groban, Department of Anesthesiology, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, USA.

Todd A. Smitherman, Department of Psychology, University of Mississippi, Oxford, MS, USA

Timothy T. Houle, Department of Anesthesiology, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, USA.

References

- 1.Mathew NT, Tfelt-Hansen P. General and pharmacological approach to migraine management. In: Olesen J, Goadsby P, Ramadan N, Tfelt-Hansen P, Welch KMA, editors. The Headaches. 3rd. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins; 2006. pp. 443–440. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edvinsson L, Linde M. New drugs in migraine treatment and prophylaxis: telcagepant and topiramate. Lancet. 2010;376:645–655. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60323-6. Epub 2010 Apr 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goadsby PJ, Sprenger T. Current practice and future directions in the prevention and acute management of migraine. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:285–298. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holroyd KA, Penzien DB, Cordingley GE. Propranolol in the management of recurrent migraine: a meta-analytic review. Headache. 1991;31:333–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1991.hed3105333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackson JL, Shimeall W, Sessums L, et al. Tricyclic antidepressants and headaches: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;341:c5222. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell JK, Penzien DB, Wall EM. Evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache: behavioral and physical treatments. [Accessed December 6, 2010];1999 November; Prepared for the US Headache Consortium. Available at: http://www.aan.com/professionals/practice/pdfs/gl0089.pdf; see “Headache – Tools”.

- 7.Penzien DB, Rains JC, Lipchik GL, Creer TL. Behavioral interventions for tension-type headache: overview of current therapies and recommendation for a self-management model for chronic headache. Current Pain and Headache Reports. 2004;8:489–499. doi: 10.1007/s11916-004-0072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rains JC, Penzien DB, McCrory DC, Gray RN. Behavioral headache treatment: history, review of the empirical literature, and methodological critique. Headache. 2005;45(Suppl 2):S92–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.4502003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nestoriuc Y, Martin A. Efficacy of biofeedback for migraine: a meta-analysis. Pain. 2007;128:111–27. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nestoriuc Y, Martin A, Rief W, Andrasik F. Biofeedback treatment for headache disorders: a comprehensive efficacy review. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2008;33:125–40. doi: 10.1007/s10484-008-9060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blanchard EB, Andrasik F, Guarnieri P, Neff DF, Rodichok LD. Two-, three, and four-year follow-up on the self-regulatory treatment of chronic headache. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1987;55:257–9. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.2.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blanchard EB. Psychological treatment of benign headache disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60:537–551. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.4.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blanchard EB, Appelbaum KA, Guarnieri P, Morrill B, Dentinger MP. Five year prospective follow-up on the treatment of chronic headache with biofeedback and/or relaxation. Headache. 1987;27:580–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1987.hed2710580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andrasik F, Blanchard EB, Neff DF, Rodichok LD. Biofeedback and relaxation training for chronic headache: A controlled comparison of booster treatments and regular contacts for long-term maintenance. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1984;52:609–615. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.52.4.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holroyd KA, Cottrell CK, O'Donnell FJ, et al. Effect of preventive (beta blocker) treatment, behavioural migraine management, or their combination on outcomes of optimised acute treatment in frequent migraine: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;341:c4871. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holroyd KA, O'Donnell FJ, Stensland M, Lipchik GL, Cordingley GE, Carlson BW. Management of chronic tension-type headache with tricyclic antidepressant medication, stress management therapy, and their combination: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285:2208–2215. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.17.2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holroyd KA, Penzien DB. Pharmacological vs. nonpharmacological prophylaxis of recurrent migraine headache: A meta-analytic review of clinical trials. Pain. 1990;42:1–13. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(90)91085-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Penzien DB, Maizels M, Rains JC. Management of headache pain. In: Elbert M, Kerns RD, editors. Behavioral and Psychopharmacological Therapeutics in Pain Management. Oxford: Cambridge University Press; In press. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adelman LC, Adelman JU, Freeman MC, Von Seggern RL. Pharmacoeconomics: The cost of prophylactic migraine treatments. Headache. 2004;44:1050–1055. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2004.4200_4.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adelman JU, Von Seggern R. Cost considerations in headache treatment. Part 1: prophylactic migraine treatment. Headache. 1995;35:479–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1995.hed3508479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldberg LD. The cost of migraine and its treatment. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11(2 Suppl):S62–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halpern MT, Lipton RB, Cady RK, Kwong WJ, Marlo KO, Batenhorst AS. Costs and outcomes of early versus delayed migraine treatment with sumatriptan. Headache. 2002;42:984–999. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2002.02228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patel NV, Bigal ME, Kolodner KB, Leotta C, Lafata JE, Lipton RB. Prevalence and impact of migraine and probable migraine in a health plan. Neurology. 2004;63:1432–1438. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000142044.22226.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rappoport AM, Adelman JU. Cost of migraine management: A pharmacoeconomic overview. Am J Man Care. 1998;4:531–545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haddock CK, Rowan AB, Andrasik F, Wilson PG, Talcott GW, Stein RJ. Home-based behavioral treatments for chronic benign headache: a meta-analysis of controlled trials. Cephalalgia. 1997;17:113–118. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1997.1702113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kernick D. An introduction to the basic principles of health economics for those involved in the development and delivery of headache care. Cephalalgia. 2005;5:709–714. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2005.00946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu J, Smith KJ, Brixner DI. Cost effectiveness of pharmacotherapy for the prevention of migraine: a Markov model application. CNS Drugs. 2010;24:695–712. doi: 10.2165/11531180-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pini LA, Cainazzo MM, Brovia D. Risk-benefit and cost-benefit ratio in headache treatment. J Headache Pain. 2005;6:315–318. doi: 10.1007/s10194-005-0219-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holroyd KA, Cottrell CK, O'Donnell FJ, Cordingley GE, Drew JB, Carlson BW, Himawan L. Effect of preventive (beta blocker) treatment, behavioural migraine management, or their combination on outcomes of optimised acute treatment in frequent migraine: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010 Sep 29;341:c4871. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4871. doi: 10.1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Friedman D, Feldon S, Holloway R, Fisher S. Utilization, diagnosis, treatment, and cost of migraine treatment in the emergency department. Headache. 2009;49:1163–1173. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luo N, Fang Y, Tan F, et al. Prevalence and burden of headache disorders: a comparative regional study in China. Headache. 2010 Nov 10; doi: 10.1111/j.1526- 4610.2010.01795.x. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]