Abstract

In March 2007, a 68 year old female was diagnosed with colonic adenocarcinoma metastatic to the lungs and a frontoparietal parafalcine lesion suspected to be a meningioma was also noted. She denied neurologic symptoms and resection of the parafalcine lesion did not occur. For 14 months, she received chemotherapy with poor response. In June 2008, she developed multiple focal neurologic deficits. Enlargement of the parafalcine brain lesion was noted on head computerized tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. Cerebral angiogram demonstrated a parafalcine mass supplied by the middle meningeal artery. All 3 modality findings confirmed a meningioma. Embolization of the middle meningeal artery with craniotomy for excision of the suspected meningioma was performed. Pathology indicated metastatic adenocarcinoma with colonic primary without evidence of meningioma. Meningiomas are the most common dural based lesions; however, a variety of dural lesions mimic meningiomas. Dural metastatic tumors mimicking meningiomas is an uncommon phenomenon, particularly when the primary location is the colon. This paper additionally discusses the differentiation of benign dural based tumors like meningiomas from malignant findings. Multiple adjunct studies can differentiate meningiomas from metastatic tumor. The definitive diagnosis is based on histopathology.

Keywords: Dural based mass, meningioma, metastatic dural based lesions

CASE REPORT

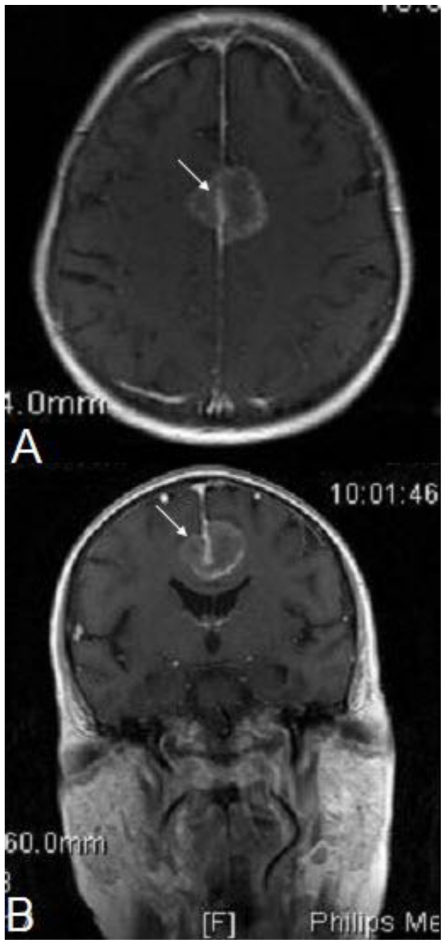

A 68 year old Caucasian female was diagnosed with stage 4 colon adenocarcinoma metastatic to the lungs, in March 2007. During the same period, a 2.5 cm × 2.3 cm × 2.7 cm enhancing frontoparietal parafalcine lesion suspected to represent a meningioma was identified on a brain MRI (Figure 1). The patient denied any neurologic symptoms and the physical exam revealed no focal neurological findings. Based on radiographic imaging, paucity of signs/symptoms, and a multidisciplinary medical team including neurosurgery consultation, resection of the meningioma-appearing lesion was not performed. For the following 14 month period, the patient received multiple chemotherapy regimens. In May of 2008, radiographic imaging of the metastatic disease to the lung and the meningioma-appearing lesion demonstrated an ineffective response to chemotherapy, as did the colonoscopic evaluation of the colon adenocarcinoma.

Figure 1.

68 year old female with stage 4 colon adenocarcinoma metastatic to the lungs. Axial (1a) and coronal (1b) gadolinium-DTPA enhanced T1-weighted MRI of the brain demonstrates an 2.5 cm × 2.3 cm × 2.7 cm enhancing frontoparietal parafalcine lesion (arrow) suspected to represent a meningioma. March 2007. MRI machine: Philips Intera; Magnet strength 1.5 Tesla; TR 450.0; TE 10.0; Flip angle 76.0 degrees.

In June 2008, the patient developed ataxia resulting in multiple falls and interval enlargement of the brain lesion was seen on radiographic imaging with clinically correlated neurological decline demonstrating both aphasia and 0–1/5 strength in the right upper and lower extremities. Her symptoms improved briefly with steroid therapy. Otherwise, all vital signs and general examination were normal.

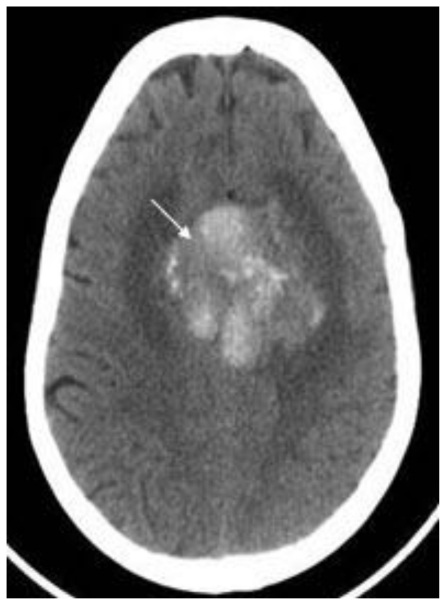

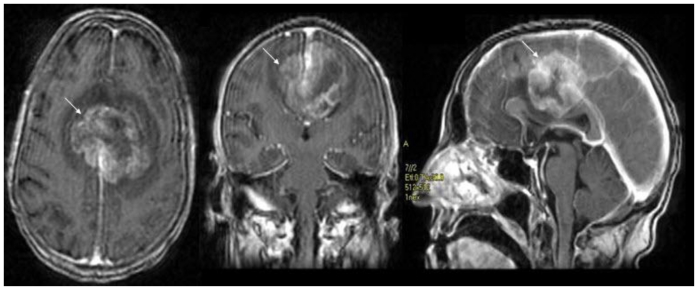

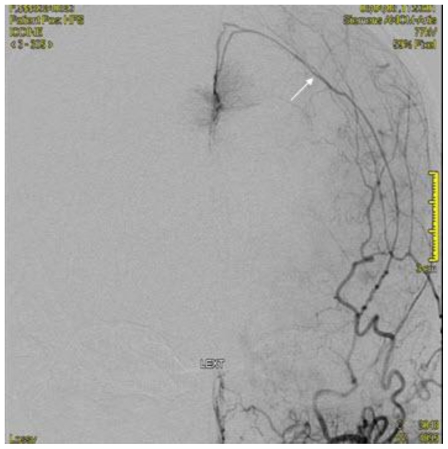

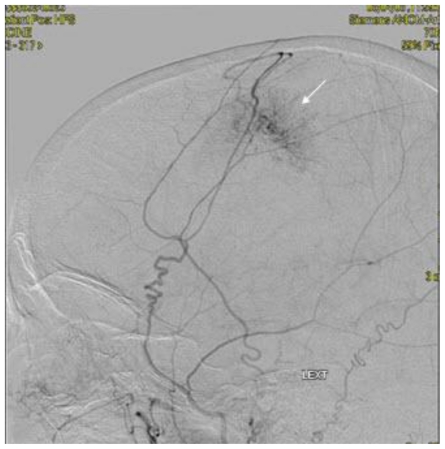

Noncontrast cranial CT demonstrated a 5.2 cm × 4.2 cm × 5.2 cm heterogeneously hyperdense extra-axial mass in midline of the vertex with calcifications (Figure 2). There was no evidence of hyperostosis or an osteolytic component of the cranial bones on bone-window CT. The lesion extended to both sides of the midline with associated edema in the frontal lobes. Regional mass effect was present and no acute hemorrhage was observed. MRI of the brain with gadolinium-diethylenetriamine penta-acetic acid (DTPA) contrast demonstrated a 5.2 cm × 4.2 cm × 5.2 cm parafalcine mass with surrounding edema and without evidence of hemorrhage (Figure 3). Bilateral cerebral angiogram demonstrated a parafalcine mass supplied by branches of the left middle meningeal artery (a branch of the external carotid artery), with an intense vascular blush persisting into the venous phase and a star-burst vascular pattern (Figures 4, 5). All 3 imaging modality results were consistent with a meningioma. Furthermore, neither additional intracranial lesions nor abnormal enhancement within the sulci or cisterns were identified, eliminating the diagnosis of leptomeningeal carcinomatosis.

Figure 2.

68 year old female with stage 4 colon adenocarcinoma metastatic to the lungs. Axial noncontrast CT of the brain in demonstrates a 5.2 cm × 4.2 cm × 5.2 cm heterogeneously hyperdense mass in midline of the vertex with calcifications (arrow) suspected to represent a meningioma. August 2008. GE Lightspeed 8-slice CT scanner.

Figure 3.

68 year old female with stage 4 colon adenocarcinoma metastatic to the lungs. Axial (3a), coronal (3b), and sagittal (3c) gadolinium-DTPA enhanced T1-weighted MRI of the brain demonstrates an 5.2 cm × 4.2 cm × 5.2 cm enhancing parafalcine mass with surrounding edema (arrow) suspected to represent a meningioma. Magnet strength: 1.5 Tesla; TR 7.2; TE 1.6; Bandwidth 20.8; Flip angle 20.0 degrees; Matrix 256.0 × 192.0 1 NEX. August 2008.

Figure 4.

68 year old female with stage 4 colon adenocarcinoma metastatic to the lungs. Bilateral cerebral digital subtraction angiogram demonstrating a parafalcine mass supplied by the left middle meningeal artery (arrow) suspected to represent a meningioma. August 2008.

Figure 5.

68 year old female with stage 4 colon adenocarcinoma metastatic to the lungs. Bilateral cerebral digital subtraction angiogram demonstrating a "star-burst" pattern vascular pattern (arrow) suspected to represent a meningioma. August 2008.

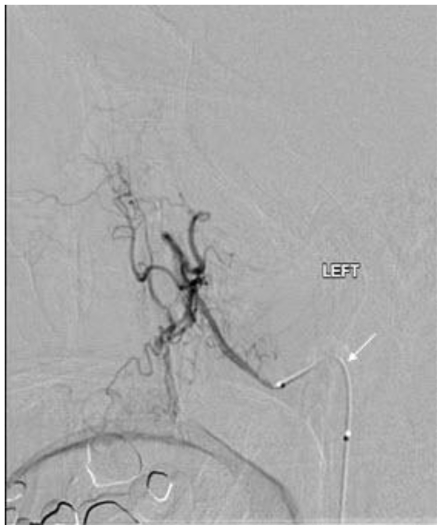

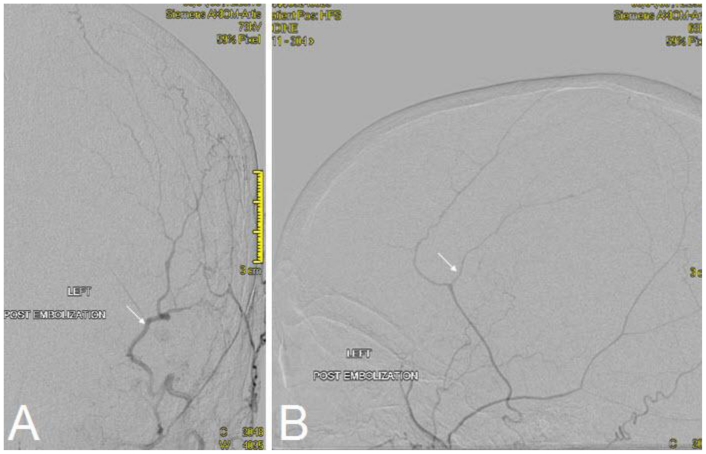

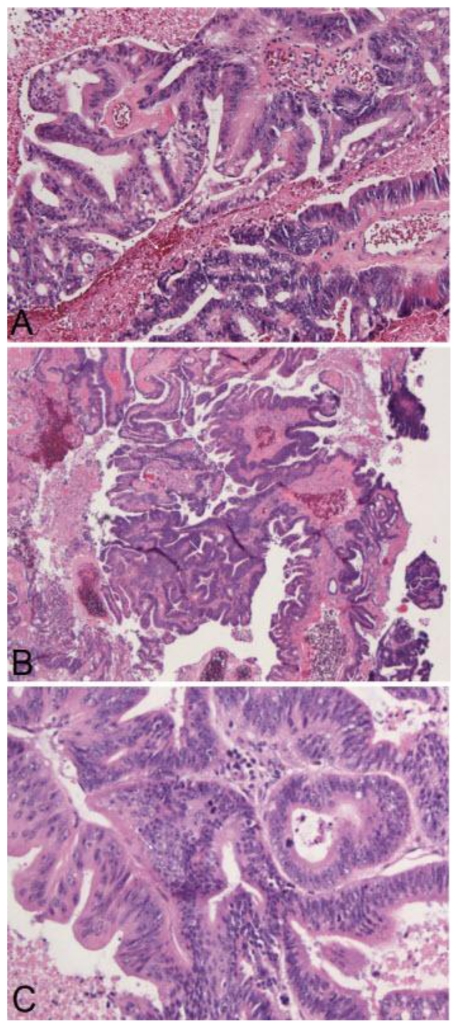

The multidisciplinary medical team now concluded that the next step in management would include management of the meningioma-appearing lesion. Embolization of the middle meningeal artery occurred using polyvinyl alcohol particles (TVA) 300–500 micrometer (Figure 6, 7). The patient subsequently underwent bilateral frontoparietal craniotomies for excision of the suspected extra-axial meningioma. Gross macroscopic examination during the neurosurgical procedure demonstrated that the tumor was grossly softened and necrotic secondary to the prior embolization therapy. Postoperative histopathologic frozen section indicated extensive necrosis with a focus of metastatic adenocarcinoma. Permanent histopathologic section indicated metastatic adenocarcinoma with colonic primary with a central hemorrhagic cavity. There was no definitive evidence of a meningioma (Figure 8). The patient had no complications during the procedure. After a discussion with the family, she was placed on comfort care.

Figure 6.

68 year old female with stage 4 colon adenocarcinoma metastatic to the lungs. Embolization of the middle meningeal artery (arrow) occurred using polyvinyl alcohol particles (TVA) 300–500 micrometer shown on digital subtraction angiogram. August 2008.

Figure 7.

68 year old female with stage 4 colon adenocarcinoma metastatic to the lungs. Postembolization view demonstrating successful embolization of the majority of the feeding external carotid artery branches (arrow). August 2008.

Figure 8.

68 year old female with stage 4 colon adenocarcinoma metastatic to the lungs. Permanent section pathology photomicrograph with hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) stains demonstrates metastatic adenocarcinoma consistent with colonic primary with a central hemorrhagic cavity (arrow). a (200X), 8b (100X), 8c (400X). August 2008.

A post-operative CT scan demonstrated evacuation of a large bilateral falcine/parafalcine mass with no residual tumor visible. Small residual hemorrhage and pneumocephalus were observed in the operative bed near the medial aspect of the frontoparietal lobes, with surrounding residual vasogenic edema in both parietal lobes. There was a reduction in the mass effect on the lateral ventricles as well as a reduction in the size of the lateral ventricles. No evidence of midline shift. The basal cisterns were preserved. The patient expired in September 2008, approximately 2 months after surgery.

DISCUSSION

Background

Cerebral metastases are the most common adult brain tumors. Cerebral metastases are generally intraaxial in location; in contrast, it is fairly uncommon to identify dural metastatic tumors (1). In fact, when a tumor presents as an isolated dural based meningeal mass with typical radiographic features as outlined in Tables 1, 2, and 3, it is typically considered to be a meningioma (2, 3), (Tables 1, 2, and 3). The origin of the majority of dural metastatic tumors are typically the breast, lung, kidney, prostate, lymphoma, or a melanoma (3, 4). Brain metastases from colon cancer is an uncommon phenomenon with a reported incidence of 1.8% to 4% in autopsy studies performed on colon cancer patients (5). Recently, unusual tumors including carcinoma of the colon, endometrium, cervix, and stomach, as well as laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma of the bladder, intravascular lymphomatosis, Ewing sarcoma, ocular melanoma, and germ cell adenocarcinoma have been identified as tumors that have metastasized to the dura (4). Furthermore and as will be discussed below, there are a variety of dural lesions that clinically and radiographically mimic meningiomas (Table 4). (4, 6, 7). In particular, dural metastatic tumors, typically of breast, prostate, renal and lung origin, may present with radiographic (CT, MRI, angiography) findings similar to those of meningiomas; however, dural metastases from colon adenocarcinoma mimicking meningiomas is a rare phenomenon (4, 7, 8, 9, 10). It has been shown that with the low incidence of colon adenocarcinoma metastasizing to the dura combined with the low incidence of dural metastatic lesions mimicking a meningioma, that the incidence of dural metastatic colon adenocarcinoma mimicking a meningioma is extremely rare (3).

Table 1.

CT findings for meningiomas and metastatic dural tumors.

| Imaging Modality | Metastatic dural lesions | Meningiomas |

|---|---|---|

| Noncontrast CT | Hypodense to mildly hyperdense appearance (in general regarding the majority of metastatic dural lesions) Hyperdense masses (regarding adenocarcinoma lesions, particularly those with a colonic primary) |

Homogeneous, intra-cranial, extra- axial, well-defined, rounded mass with a broad dural attachment Elevated attenuation coefficient/Hyperdense |

| CT with iodinated IV contrast | High and densely homogeneous contrast enhancement | Marked contrast enhancement |

| CT (additional findings) | Present as a subdural hematoma or a tumor mass Hypervascularity Large areas of necrosis inside the tumor with associated large areas of surrounding edema and with associated hemorrhage Cerebral metastatic tumors are usually intra-axial |

Moderate circumferential edema and mass effect Possible hyperostosis Dural tail sign Calcifications |

Table 2.

MRI findings for meningiomas and metastatic dural tumors.

| Imaging Modality | Metastatic dural lesions | Meningiomas |

|---|---|---|

| Noncontrast MRI (T1) | Hypointense areas on T1-weighted images | Hypo- or isointense on T1-weighted images |

| Noncontrast MRI (T2) | Hyperintense areas on T2-weighted images | Variable signal intensity on T2- weighted images; Typically isointensity or slightly hyperintensity |

| MRI with gadolinium-DTPA contrast (T1) | Distinctly hyperintense lesion Enhancement of a dural tail Best imaging modality |

Intense homogeneous or heterogeneous enhancement Well-defined margin |

| MRI (additional findings) | Dural tail sign is a possibility | Dural tail sign Star-burst sign CSF cleft |

Table 3.

Angiographic findings for meningiomas and metastatic dural tumors.

| Imaging Findings | Metastatic dural lesions | Meningiomas |

|---|---|---|

| Blood supply | Multiple etiologies | External carotid artery branch vessel Middle meningeal artery typically |

| Classic features | Accumulation of contrast agent in the capillary phase | Star-burst vascular pattern Mother-in-law sign |

Table 4.

Differential diagnosis of dural-based lesions.

| Type of Dural-Based Lesions | Differential Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Neoplastic | Actinomycoma, Carcinomas, Chondromas, Ependymoma, Ewing sarcoma, Gliosarcomas, Hemangiopericytomas, Hodgkin’s disease, Inflammatory pseudotumors, Lymphoma, Melanoma, Melanocytomas, Neuroblastoma, Plasmacytoma, Sarcomas, Solitary fibrous tumors, and Xanthoastrocytoma |

| Metastatic Dural Tumors | Metastatic disease from Adenoid carcinoma, Breast, Colon, Gallbladder, Kidney, Leiomyosarcoma, Lung, and Prostate |

| Inflammatory | Castleman disease, Neurosarcoidosis, Plasma cell granulomas, Rheumatoid nodules, Rosai-Dorfman disease, and Xanthomas |

| Infectious | Human immunodeficiency virus-1 associated with leiomyosarcomas, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and Mycobacterium avium complex |

| Other | Extramedullary hematopoiesis |

A distinctive feature of dural metastatic colon adenocarcinoma is that the patient rarely presents symptomatically while the primary tumor is not discovered. There is a poor life expectancy associated with colon adenocarcinoma metastatic to the brain with a reported range of 2 to 44 weeks because the metastatic brain lesions associated with colon adenocarcinoma are typically a late finding, the point at which multiple other organ systems are already affected (5). For example, the symptoms associated with the metastatic brain lesion commonly correlate with X-ray evidence of pulmonary metastatic disease in 85% of cases and hepatic metastatic disease in 50–76% of cases (5). When evaluating for cerebral metastatic disease, the physician should promptly order carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA); bone scan; positron emission tomographic (PET) scanning; MRI of the brain, spine, or both; lumbar puncture; and CT scanning or MRI of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis (11). The evaluation modalities to be discussed in this case report include CT, MRI, and angiography.

Differentiation---Imaging of Meningiomas

The classic CT scan findings for meningiomas are listed in Table 1 (1, 11, 12), (Table 1). The classic MRI findings for meningiomas, irrespective of histological subtype, are included in Table 2 (3, 11, 12), (Table 2). In particular for MRI, post-contrast T1-weighted images using intravenous gadolinium-DTPA demonstrate intense homogeneous or heterogeneous enhancement with a well-defined margin for meningiomas approximately 95% of the time (3, 11). Additionally, the dural tail sign (noted on CT and MRI) appears as an area of enhancement in the dura mater adjacent to the tumor. Finally, the classic selective angiography findings for meningiomas are included in Table 3 (4, 12), (Table 3). Concerning the "mother-in-law" sign noted in cerebral angiography, this refers to a persistent homogenous tumor blush that appears early and persists until later after contrast injection during angiography (12). All 3 of the angiographic findings were evident in this case report.

Differentiation---Imaging of Metastatic Dural Tumors

Dural metastatic lesions generally present as either a subdural hematoma or a tumor mass, the latter contributing to the diagnostic dilemma in differentiating a dural metastatic lesion versus a meningioma (11). Metastatic brain lesions have common CT findings. First, there are areas of necrosis inside the tumor with associated large areas of surrounding edema. Second, on non-contrast imaging there is a hypodense to mild hyperdense appearance; with strong and homogeneous enhancement of the lesion after contrast administration (5). Additionally, brain metastatic lesions typically demonstrate hypervascularity, intraaxial location, and necrosis associated with hemorrhage (13).

Concerning specifically adenocarcinoma lesions and moreso those of a colonic nature, multiple case reports state that they present as hyperdense masses on CT and this finding is related to multiple mechanisms (14). First, the hyperdensity may be a result of hemorrhage within the tumor; second, the tight and densely packed cell structure of the tumor; third, the occurrence of calcium microdeposits within the metastasis; or fourth, mucoid degeneration may have occurred (5, 14). MR imaging of brain metastases of colon adenocarcinoma demonstrates hypointense areas on T1-weighted images and hyperintense areas on T2-weighted images (14). For further delineation, contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images will show a distinctly hyperintense lesion and are considered the best modality for radiologic diagnosis; however, speculation ensues when enhancement of the dural tail occurs because this was once specific for meningiomas, but is now nonspecific (11, 14). Concerning angiography, when an accumulation of contrast agent in the capillary phase is evident, this may be typical of metastatic disease (12). This additional diagnostic clue is a significant reason why a cerebral angiogram should be performed in all patients with a history of primary malignancy and a dural-based lesion in order to guide therapeutic intervention. (Tables 1, 2, and 3)

Prior case report comparisons between meningiomas and metastatic dural tumors

In a literature review of multiple case reports in which the radiological features all represented meningiomas but the histopathological correlation ultimately demonstrated an intracranial metastatic lesion, there were similar radiographic findings in all of the cases. First, the CT scans demonstrated a well circumscribed, extra-axial, dural-based, hyperdense, contrast-enhancing lesion. Second, the angiograms demonstrated vascular supply from the external carotid artery. Third, the MRI scans demonstrated a "dural tail" sign, which as indicated previously was once indistinguishable from a meningioma (2, 13).

According to Lyons et al., 5 reasons for a diagnostic dilemma between meningioma and metastatic disease may occur, which make preoperative differentiation and subsequent treatment planning (conservative vs. radiosurgery) difficult. These include high attenuation values on CT, tumor location, the "dural tail sign," the non-specific, asymptomatic general condition of patients, and calcifications. As of 2007, 29 cases of dural metastases imitating a meningioma have been reported. As of 2008, the number of cases currently is less than 40 which the most common primaries being the prostate, breast, and kidney (2). These 5 categories are reviewed below.

First, the enhancement pattern on CT scanning, with high attenuation values on CT, for metastatic colon adenocarcinoma is similar to that of intracranial meningiomas (1). Second, cerebral metastases are typically located in the brain or cerebellum and infrequently in the meninges; moreover, they can be isolated or diffuse lesions (2). When they are located in the meninges (an intra-cranial, extra-axial location) and appear as an isolated form on radiological appearance, this may suggest a primary tumor such as a meningioma and confusion might occur, particularly when the macroscopic form with its lobular growth pattern also demonstrates findings suggestive of a meningioma because they are indistinguishable (1, 2, 3). Third, the enhancement of the meninges adjacent to the meningiomas or "dural tail sign" nonspecific for meningiomas on CT/MRI and can be associated with multiple etiologies of dural-based lesions, including meningeal metastases (1, 3, 4, 11). Fourth, patients with a meningioma typically are asymptomatic as can the patient with metastatic disease; however, patients with metastatic brain lesions typically demonstrate symptoms that result from hemorrhage or mass effect correlating with the tumor location (1, 2, 12). In an asymptomatic patient with no prior evidence of cancer (unlike the presented case) and an absence of hemorrhage on neuroradiological imaging, the diagnosis would be highly suggestive of a meningioma. In contrast, multiple case reports in the literature demonstrate that a rapid worsening in the patient's symptoms are indicative of metastatic disease; and subsequently, monitoring of the patient's course is paramount (3, 4).

Regarding the fifth category, findings that are rare in metastatic brain tumors but common in benign meningiomas, like calcifications, may complicate the diagnosis. Typically, the presence of calcification within an intracranial mass lesion is an indicator of slow growth or benign nature (15). Intracranial lesions with calcifications include meningiomas, gliomas, aneurysms, angiomas, and granulomatous lesions (15). A diagnostic dilemma surfaces when a high-density area on CT cranial scans is visualized because even though calcification may be a possibility, other possibilities include intratumoral hemorrhage or mucoid degeneration, thus expanding our differential diagnosis even though metastatic brain tumors uncommonly demonstrate calcification on CT scans (15). Higuchi et al. suggest that what was originally identified as a high density mass on precontrast CT scans and correlated with meningioma, actually was later diagnosed as a microhemorrhage within a metastatic dural-based tumor (3). Typically, the homogeneously hyperdense appearance of meningiomas on CT is secondary to calcification; contrastingly, the homogeneously hyperdense appearance of adenocarcinoma is secondary to the aforementioned hemorrhages, mucoid degeneration, calcification, or dense cell structure (3). This case revealed pathology demonstrating metastatic adenocarcinoma with colonic primary with a central hemorrhagic cavity. Moreover, through the year 1994 there were only 25 cases of calcified intracranial metastatic carcinoma in the literature with the most common primary sites being breast (7 cases), lung (5 cases) and colon (4 cases) (15).

Differential Diagnoses

There are a multitude of dural-based lesions (Table 4). The differential diagnosis includes those disease entities that are incidental and benign to those that are symptomatic and malignant. Furthermore, the dural-based lesions can be classified into inflammatory/infectious vs. neoplastic categories (1).

The aforementioned neoplastic category includes metastatic dural-based tumors, which are significantly less common than intraparenchymal disease. Additionally, carcinomas are the most common type of malignant tumor presenting as a dural-based metastasis and include the following primary origin sites: pituitary, breast, lung, colon, gastric, prostate, renal cell, and adenoid cystic adenocarcinoma (1). Originally, breast adenocarcinoma was considered the most common type of carcinoma that presented with dural metastases; however, recent data suggests that prostate adenocarcinoma may be the most common metastatic carcinoma of the dura (1). Many of these same neoplastic and nonneoplastic lesions have the ability to simulate meningiomas radiographically (CT, MRI, angiography) and clinically (1, 2, 4, 7), (Table 4). According to Table 4, metastases from different neoplasms with primaries located in the prostate, lung, kidney, gallbladder, leiomyosarcoma, adenoid carcinoma, breast, and colon have the ability to mimic meningiomas (1, 2, 4, 7). Additionally, there are other metastatic dural tumors reported in the literature that include pituitary adenoma, pituitary carcinoma, neuroblastoma, chondrosarcoma, primary epitheliod sarcoma, carcinoid, and osteochondroma; however, these have not been reported as simulating meningiomas (1, 2, 4, 11).

Mechanism

Three theoretical mechanisms explain the etiology of dural metastatic lesions. First, dural metastases can develop from direct extension of skull/calvarial metastases, as is the predominate case in lung, prostate, breast carcinomas and in Ewing sarcoma (1, 16). Second, dural metastases can develop from dissemination through the systemic circulation, particularly arterial when no evidence of skull invasion exists (16). In this case, hematogenous spread is the presumed mechanism, and it is theorized that hematogenous metastases travel along the meningeal arteries led to the dural involvement (1, 4, 17). Furthermore, it is possible that most metastases occur via the arterial supply with a prior associated venous implantation in the lungs (12). Third and less common, dural metastases can occur from outward progression of a cortical brain metastasis; in other words, a direct tumor infiltrate (1, 16).

Differentiation

There are multiple methods to potentially assist in the differentiation between intracranial meningioma and metastatic dural lesions. First, functional MRI might provide additional detail to lead to a more definitive diagnosis because standard MRI might be unable to differentiate between the two lesions (2, 11). Second, MR spectroscopy may assist in the differentiation because of its ability to detect a pattern of lipid and/or lactate signals specific to metastatic tumors (1, 4). This diagnostic test; however, must be performed prior to embolization and is also restricted to very large metastases (4, 18). These findings are based on ratios of N-acetylaspartate (NAA), choline (Cho), NAA/Cho + creatine (Cr), lactate/Cr, and alanine/Cr ratios (19). Third, both cytologic study of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serologic study can assist in the differentiation between meningiomas and metastatic tumors (4, 17, 20–21). Fourth, dynamic perfusion MRI (DPRMI) demonstrates different perfusion-sensitive characteristics when comparing dural metastases and meningiomas (4). DPRMI provides additional information regarding the vascularity of a tumor that is not available with conventional MRI (4). Moreover, it maps the cerebral blood volume and calculates the relative cerebral blood volume (rCBV), which is the ratio between the CBV in the tumor and the CBV in the white matter. This determination is useful because studies demonstrate that meningiomas typically have a high rCBV; whereas dural metastatic lesions typically have a low rCBV (Table 5), (11).

Table 5.

Additional differentiation techniques between meningiomas and metastatic dural lesions.

| Method | Mechanism | Metastatic/Malignant Tumors | Meningiomas/Benign Tumors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional MRI | Provides additional detail to assist in differential diagnosis as standard MRI might be unable to differentiate between the two lesions | Additional detail | Additional detail |

| MR Spectroscopy | Detects a pattern of lipid and/or lactate signals specific to metastatic tumors Must be performed prior to embolization Restricted to very large metastases |

Malignant brain tumors have lower NAA/Cho, NAA/Cho + Cr, NAA/Cr and higher lactate/lipid, lactate/Cr tumor ratios when compared to benign brain tumors | Meningiomas have a high alanin/Cr ratio |

| Cytologic study of CSF and serologic study | Assists in the differentiation between meningiomas and metastatic tumors | Unique cytomorphology varies according to the organ of origin Well-defined cell borders Abundant cytoplasm |

Rare spread of cells into the cerebrospinal fluid |

| Dynamic perfusion MRI (DPRMI) | Demonstrates different perfusion-sensitive characteristics between dural metastases and meningiomas DPRMI provides additional information regarding the vascularity of a tumor that is not available with conventional MRI Maps the cerebral blood volume and calculates the relative cerebral blood volume (rCBV), which is the ratio between the CBV in the tumor and the CBV in the white matter |

Dural metastatic lesions typically have a low rCBV | Meningiomas typically have a high rCBV |

At times, it may be difficult to preoperatively differentiate dural metastases from meningioma both clinically and radiographically (CT, MR, and angiography). In general, when disseminated disease is absent, the probability of a solitary, enhancing, soft-tissue lesion being a meningioma is high; however, when disseminated disease is present, the differentiation between metastatic disease versus meningioma using conventional imaging modalities may be difficult (11). Physicians must be particularly attentive and cautious when caring for patients with a history of cancer who present with new symptoms or imaging evidence of dural-based lesions. Ordinary metastases must be considered in the differential diagnosis even when multiple radiographic studies indicate a meningioma and histopathologic correlation is necessary for final definitive diagnosis.

The patient in this case report demonstrated a calcified tumor with a prolonged course of a paucity of neurologic symptoms that suggested a meningioma rather than a metastatic lesion; but, even with these signs/symptoms and radiological studies, brain metastatic disease must be incorporated into the differential diagnosis of calcified intracranial lesions because of the implications related to postponing surgical intervention if a meningioma is mistakenly diagnosed (3, 15, 17).

TEACHING POINT

There is a broad differential diagnosis of both dural-based lesions alone and dural-based lesions that mimic meningiomas. Histopathological correlation as well as understanding the clinical history of the patient assist in obtaining the conclusive diagnosis.

There are unique findings on radiographic studies as well as adjunct studies that can assist in comparing and constrating meningiomas and metastatic dural based lesions.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CT

computed tomography

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- DTPA

gadolinium-diethylenetriamine penta-acetic acid

- TVA

polyvinyl alcohol particles

- DPMRI

dynamic perfusion magnetic resonance imaging

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

REFERENCES

- 1.Lyons MK, Drawkowski JF, Wong WW, Fitch TR, Nelson KD. Metastatic Prostate Carcinoma Mimicking Meningioma. Case Report and Review of the Literature. The Neurologist. 2006;12(1):48–51. doi: 10.1097/01.nrl.0000186809.04283.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tagle P, Villanueva P, Torrealba G, Huete I. Intracranial Metastasis or Meningioma. An Uncommon Clinical Diagnostic Dilemma. Surg Neurol. 2002;58:241–5. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(02)00831-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Higuchi M, Fujimoto Y, Miyahara E, Ikeda H. Isolated dural metastasis from colon cancer. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 1997;99:135–137. doi: 10.1016/s0303-8467(96)00599-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shigeo O, Kurokawa R, Yoshida K, Kawase T. Metastatic Adenocarcinoma of the Dura Mimicking Petroclival Meningioma. Neurology Med Chir (Tokyo) 2004;44:317–320. doi: 10.2176/nmc.44.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruelle A, Gambini C, Macchia G, Andrioll G. Brain metastasis from colon cancer. J. Neurosurg. Sci. 1987;31:33–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson MD, Powell SZ, Boyer PJ, Weil RJ, Moots PL. Dural lesions mimicking meningiomas. Human Pathology. 2002;33:121–1226. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.129200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lippman SM, Buzaid AC, Iacono RP, et al. Cranial Metastases from Prostate Cancer Simulating Meningioma: Report of Two Cases and Review of the Literature. Neurosurgery. 1986;19(5):820–823. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198611000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toye R, Jeffree MA. Metastatic bronchial adenocarcinoma showing the "meningeal sign": a case note. Neuroradiology. 1993;35:272–273. doi: 10.1007/BF00602612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kleinschmidt-De Masters BK. Dural metastases. A retrospective surgical and autopsy series. Archives Pathology Laboratory Medicine. 2001;125:880–887. doi: 10.5858/2001-125-0880-DM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rumana CS, Hess KR, Shi WM, Sawaya R. Metastatic tumors with dural extension. Journal of Neurosurgery. 1998;89:552–558. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.89.4.0552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmidt GW, Miller NR. Metastatic breast carcinoma mimicking basal skull meningioma. Clinical Ophthalmology. 2007;1(3):343–346. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lath CO, Khanna PC, Gadewar S, Patkar DP. Intracranial metastasis from prostatic adenocarcinoma simulating a meningioma. Australasian Radiology. 2005;49:497–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1673.2005.01473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahn JY, Kim NK, Oh D, Ahn HJ. Thymic carcinoma with brain metastasis mimicking meningioma. Journal of Neuro-Oncology. 2002;58:193–199. doi: 10.1023/a:1016225915434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neroni M, Artico M, Pastore FS, Esposito S, Fraioli B. Diaphragma Sellae Metastasis from Colon Carcinoma Mimicking a Meningioma. Neurochirurgie. 1999;45(2):160–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Umezu H, Sano T, Aiba T, Unakami M. Calcified Intracranial Metastatic Tumor Mimicking Meningioma. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1994;34:108–110. doi: 10.2176/nmc.34.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laigle-Donadey F, Taillibert S, Mokhtari K, Hildebrand J, Delattre JY. Dural metastases. Journal of Neuro-Oncology. 2005;75:57–61. doi: 10.1007/s11060-004-8098-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takahaski JA, Llena JF, Hirano A. Pathology of cerebral metastases. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1996;7:345–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang TW, Young YH. Differentiation between cerebellopontine angle tumors in cancer patients. Otol Neurotol. 2002;23:975–979. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200211000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bulakbasi N, Kocaoglu M, Ors F, Tayfun C, Ucoz T. Combination of Single-Voxel Proton MR Spectroscopy and Apparent Diffusion Coefficient Calculation in the Evaluation of Common Brain Tumors. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2003;23:225–233. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ehya H, Hajdu SI, Melamed MR. Cytopathology of Nonlymphoreticular Neoplasmas Metastatic to the Central Nervous System. Acta Cytologica. 1981;25(6):598–610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bigner SH, Johnston WW. The Cytopathology of Cerebrospinal Fluid. Acta Cytologica. 1981;25(5):461–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]