Abstract

We report a 52 year old patient presenting with a bladder stone formed over a migrated intrauterine device (Copper–T). Her history was pertinent for intrauterine contraceptive (IUCD) device placement 10 years back. Investigations included plain ultrasound of abdomen, X-ray of abdomen, urinalysis, and urine culture. Ultrasound and plain X-ray of the pelvis confirmed a bladder stone formed over a migrated copper-T intrauterine device. The device was removed through suprapubic cystolithotomy. Of all the reported cases of vesical stone formation over a migrated IUCD, this case is unique as the patient was an elderly - 52 year old - female. All previously reported cases are of younger age.

Keywords: Bladder stone, intravesical migration, IUCD, Copper–T, intrauterine device

CASE REPORT

A 52 year old woman (P7L4A0) presented to our institution with complaints of pain in the lower abdomen off and on for 2 years and burning micturation for 3 months. There was a history of insertion of Copper-T intrauterine device 11 years ago. The threads of the IUCD were missing. Per vaginal clinical examination did not reveal any threads of Copper-T (IUCD). Her urine routine examination report revealed presence of numerous pus cells. Urine culture revealed no growth of any organism. Ultrasound of the urinary bladder revealed a T-shaped echogenic structure measuring 4 × 1.17 cm with posterior acoustic shadowing (Fig. 1). It was freely mobile with change in position, occupying the dependent part of the bladder. X-ray pelvis clearly showed a radio-opaque vesical calculus formed around a Copper–T Device (Fig. 2). Patient was subjected to suprapubic cystolithotomy and a T-shaped stone was extracted (Fig 4). The bladder was closed primarily and patient made an uneventful recovery. On fracturing the stone, both the arms of the Copper-T along with the thread could be identified (Fig. 5). The patient made an uneventful recovery and was discharged on the 5th post-operative day.

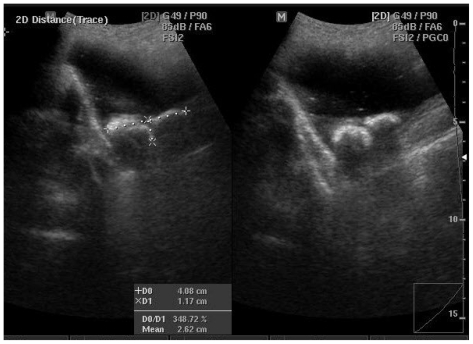

Figure 1.

52 year old woman vesical with calculus encrusted around a Copper-T intrauterine contraceptive device which migrated to the urinary bladder. Transabdominal grayscale ultrasound of the pelvis. An echogenic T-shaped object with posterior acoustic shadowing is identified in the urinary bladder, measuring 4.1 × 1.2 cm and consistent with the encrusted Copper-T device.

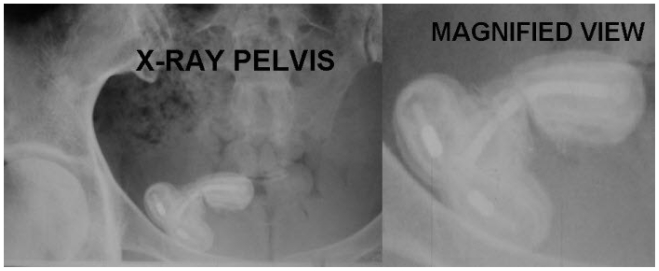

Figure 2.

52 year old woman with vesical calculus encrusted around a Copper-T intrauterine contraceptive device which migrated to the urinary bladder. X-ray of the pelvis demonstrates a vesical calculus encrusted around a Copper-T device which migrated to the urinary bladder.

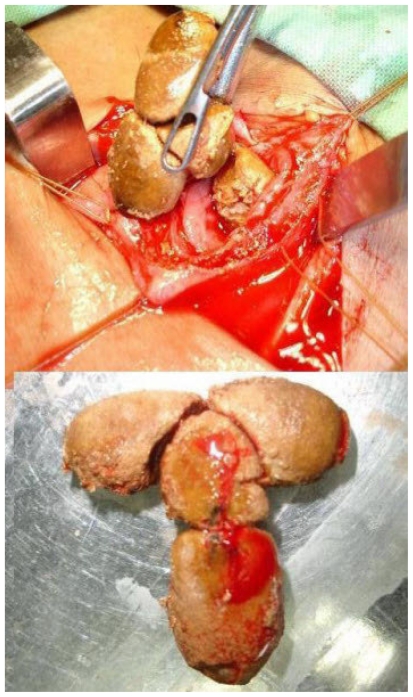

Figure 4.

52 year old woman with vesical calculus encrusted around a Copper-T intrauterine contraceptive device which migrated to the urinary bladder. Intraoperative (top) and removed (bottom) vesical calculus.

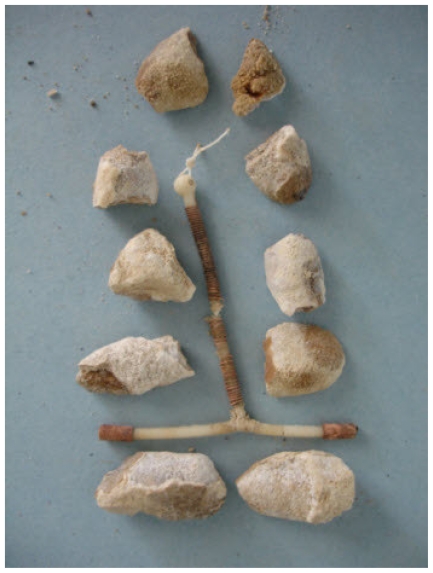

Figure 5.

Postoperative image after removal of stone. Vesical calculus encrusted around a Copper-T intrauterine contraceptive device which migrated to the urinary bladder. Copper-T device with the thread can be clearly identified on fracturing the stone.

DISCUSSION

Intrauterine devices are associated with many early and late complications, including perforation and migration into adjacent structures (1). The importance of post-insertion follow up and the need for awareness of migration of IUCD including intravesical migration cannot be overemphasized. Bladder stones develop very occasionally because of the presence of foreign bodies in the bladder (2). IUCD has been used as an effective, safe and economic method of contraception for many years. Since its introduction, many complications have been reported which include dysmenorrhoea, hypermenorrhoea, pelvic infection, pregnancy, septic abortion, uterine perforation and migration into adjacent organs (3). Although the process of IUCD migration into the bladder is gradual and accompanied with complications such as cystitis, hematuria, and pelvic pain, most of the perforations occur at the time of insertion. Pelvic ultrasound examination should be performed in every patient with unexplained lower abdominal pain who is known to carry an intrauterine contraceptive device (4). Factors raising suspicion of uterine rupture include insertion of the device by inexperienced persons, inappropriate position of the IUCD, susceptible uterine wall due to multiparity, and a recent abortion or pregnancy (5).

Only 31 cases of complete or incomplete migration of IUD into the bladder and calculus formation have been reported in the literature by 2006 (6).

All IUCDs are radio-opaque; therefore, plain abdominal radiography may be used for detection of the IUCD as well as ultrasonography and CT scan. Transvaginal ultrasonography provides the best view for locating the IUCD, but it restricts the space for its simultaneous removal. Magnetic resonance imaging is not contraindicated in copper IUCDs (7). Stones formed around foreign bodies may be composite of struvite and carbonate apatite formed around non-absorbable surgical materials in urine with urease producing (proteus mirabilis) bacterial infection (8).

TEACHING POINT

Spontaneous migration of intrauterine devices into the bladder and secondary stone formation is a rare complication and should be taken into consideration while performing ultrasound of the bladder.

Figure 3.

52 year old woman with vesical calculus encrusted around a Copper-T intrauterine contraceptive device which migrated to the urinary bladder. X-ray Pelvis – magnified view. Clearly seen is the frame of the Copper-T device which is encrusted by a vesical calculus.

ABBREVIATIONS

- IUCD

Intrauterine contraceptive device

- CT

Computed tomography

REFERENCES

- 1.Ozgür A, Sişmanoğlu A, Yazici C, Coşar E, Tezen D, Ilker Y. Intravesical stone formation on intrauterine contraceptive device. Int Urol Nephrol. 2004;36(3):345–8. doi: 10.1007/s11255-004-0747-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parra Muntaner L, Rivas Escudero JA, Gomez S, Borrego Hernando J, Garcia Alonso J. Bilateral obstructed uropathy secondary to encrusted cystitis. Report of a case. Arch Esp Urol. 1996;49(8):870–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katara Avinash N, Chandiramani Vinod A, Pandya Shefali M, Nair Nita S. Migration of intrauterine contraceptive device into the appendix. Indian Journal of Surgery. 2004 Jun;66(3):179–180. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caspi B, Trainperson D, Appelman Z, Kaplan B. Penetration of the bladder by a perforating intrauterine contraceptive device: a sonographic diagnosis. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2003;7(6):458–460. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1996.07060458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Junceda Avello E, Gonzalez Torga L, Lasheras Villanueva J, De Quiros AGB. Uterine perforation and vesical migration of an intrauterine device. Case observation. Acta Ginecol (Madr) 1977;30:79–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demirci D, Ekmekcioglu O, Demirtas A, Gulmez I. Big bladder stones around an intravesical migrated intrauterine device. Int Urol Nephrol. 2003;35:495–6. doi: 10.1023/b:urol.0000025624.15799.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Speroff L, Fritz MA. Intrauterine contraception The IUD. In: Speroff L, Fritz MA, editors. Clinical gynecologic endocrinology and infertility. 17th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. pp. 975–95. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Douenias R, Rich M, Badlani G, Mazor D, Smith A. Predisposing factors in bladder calculi. Review of 100 cases. Urology. 1991;37(3):240–3. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(91)80293-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]