Abstract

Plunging ranulas are rare cystic masses in the neck that are mucous retention pseudocysts from an obstructed sublingual gland. They “plunge” by extending inferiorly beyond the free edge of the mylohyoid muscle, or through a dehiscence of the muscle itself, to enter the submandibular space. Imaging demonstrates a simple cystic lesion in the characteristic location and can be used to delineate relevant surgical anatomy. Surgical excision of the collection and the involved sublingual gland is performed for definitive treatment. We present a case of plunging ranula in a 44 year old female who presented with a painless, slowly enlarged neck mass. Plunging ranulas should be considered in the differential diagnosis of cystic neck masses, specifically when seen extending over, or through, the mylohyoid muscle.

Keywords: ranula, plunging ranula, diving ranula, cystic neck masses

CASE REPORT

A 44 year-old female presented to an outpatient facility for evaluation of a slowly-enlarging painless neck mass. She had noticed the mass 1.5 years earlier, but had become recently concerned because of its effect on her appearance. The mass was palpated on physical examination and direct visualization was attempted. Although the classical features for a ranula, such as fluctuant, translucent bluish swelling under the tongue, were not definitely appreciated, the diagnosis was suspected and a CT was obtained for further evaluation.

The CT of the neck with contrast showed a non-enhancing, homogenous, smoothly-marginated, non-septated mass measuring 6.7 × 2.2 cm × 4.5cm (Figures 1–3). The mass was located in the right sublingual space and extended posterolaterally over the free edge of the mylohyoid muscle, resulting in mass effect with displacement of the parapharyngeal and mucosal pharyngeal spaces and slight airway deviation. Additionally, a “tail sign” was appreciated with smooth tapering anteriorly from the submandibular space into the sublingual space, confirming the clinical diagnosis of plunging ranula. The term “giant ranula” could also be used given the large size of the ranula and its mass on the parapharyngeal space. The patient was informed of the benign diagnosis and chose to have follow-up rather than immediate resection. However, two months later, the patient developed pain at the site of the plunging ranula, chills, and mild stridor. An infection was suspected and a repeat CT of the neck with contrast was obtained. It showed slight enlargement of the mass, now measuring 6.9 × 3.7 × 4.0 cm, with increased airway deviation, new adjacent fat stranding, and new rim enhancement (Figures 4–8). Findings were consistent with secondary infection of the plunging ranula.

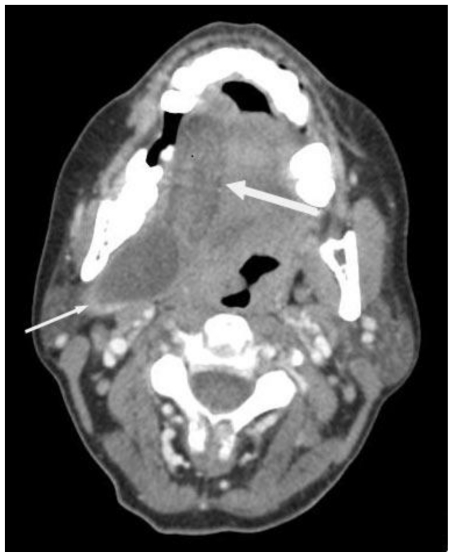

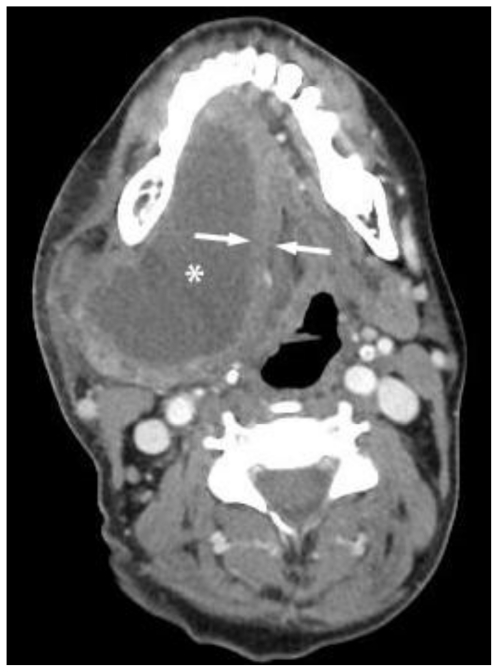

Figure 1.

Initial contrast enhanced axial Computed Tomography - 100 cc of Omnipaque-300 (KVp 120, mA 20 * 3572ms). 44-year-old female with plunging ranula - Superior aspect of the lesion - Shows a non-enhancing, water-density mass from the right sublingual space displacing the tongue to the left. A large component of the mass extends posterolaterally into the submandibular space (small arrow). Mass effect can be appreciated with displacement of the parapharyngeal and mucosal pharyngeal spaces. The lesion measures 6.7 × 2.2 × 4.5 cm and is of water-density. It is non-enhancing, homogenous, smoothly-marginated, and without internal septations. Smooth tapering anteriorly into the sublingual space, forming the “tail sign,” is seen, but better appreciated on stack images (large arrow).

Figure 3.

Initial contrast enhanced axial Computed Tomography - 100 cc of Omnipaque-300 (KVp 120, mA 20 * 3572ms). 44-year-old female with plunging ranula. A more inferior level, at the level of the hyoid bone. The geniohyoids (labeled with “*”) can be appreciated inserting on the hyoid bone. The dashed lines show the posterolateral free-margins of the mylohyoid muscle. The lesion measures 6.7 × 2.2 × 4.5 cm and is of water-density. It is non-enhancing, homogenous, smoothly-marginated, and without internal septations. The posterior aspect of the lesion can be seen extending posteriorly over the approximate location of the free edge of the mylohyoid bone.

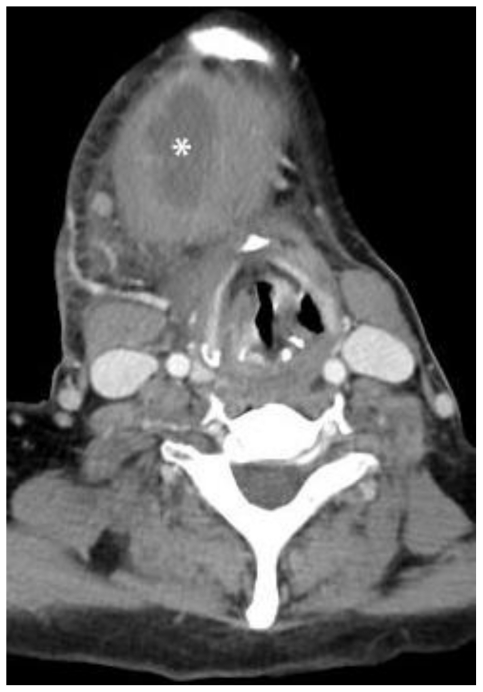

Figure 4.

Follow-up contrast enhanced axial Computed Tomography performed 2 months later - 80 cc of Omnipaque-300 (KVp 120, mA 20 * 3575 ms) 44-year-old female with infected plunging ranula. Superior aspect of the lesion (labeled with *). The mass has unchanged anatomic relationships, but has slightly enlarged and now measures 6.9 × 3.7 × 4.0 cm. It remains homogenous, smoothly-marginated, and without internal septations. Thick rim-enhancement is now seen, consistent with secondary infection. Mass effect with tracheal deviation and compression is worse and there is new right submandibular and cervical reactive lymphadenopathy. The mass was surgically excised and pathologically proven to be a plunging ranula.

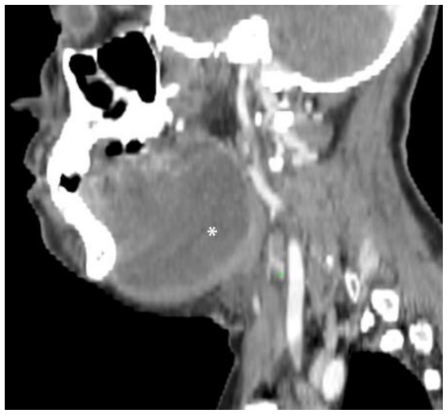

Figure 8.

Follow-up contrast enhanced Computed Tomography performed 2 months later - 80 cc of Omnipaque-300 (KVp 120, mA 20 * 3575 ms). 44-year-old female with plunging ranula. Sagittal reconstruction to the right of midline. The mass (labeled with *) has unchanged anatomic relationships, but has slightly enlarged and now measures 6.9 × 3.7 × 4.0 cm. It remains homogenous, smoothly-marginated, and without internal septations. Thick rim-enhancement is now seen, consistent with secondary infection. Mass effect with tracheal deviation and compression is worse and there is new right submandibular and cervical reactive lymphadenopathy. The mass was surgically excised and pathologically proven to be a plunging ranula.

A secure airway was established, antibiotics were administered, and the mass and the involved sublingual gland were surgically resected. The patient tolerated the surgery without complication and there was no clinical evidence of recurrence on a subsequent appointment.

DISCUSSION

Ranulas are retention collections of extravasated salivary secretions that form unilocular pseudocysts in the submandibular area. Ranulas superior to the mylohyoid muscle appear as a translucent bluish swelling under the tongue, resembling a frog’s underside. The term “Rana” is Latin for “frog.” Most plunging ranulas have this visible component, while all simple ranulas have it. Ranulas in the sublingual space are visible on physical exam. Occasionally, a plunging ranula will not have the typical sublinguinal component as it might arise from an ectopic gland, and thus may not be seen on physical exam. Ranulas are termed “plunging” or “diving” when they extend beyond the sublingual space and “plunge” inferiorly into the neck. Ranulas occur when salivary duct obstruction results in increased pressure, duct rupture, and formation of a retention pseudocyst. Occasionally, ranulas can result from an obstruction of the submandibular gland or a minor salivary gland [1], however these do not form into plunging ranulas. Plunging ranulas form only in the sublingual gland because it is the only salivary gland that secretes continuously [2]. The prevalence of simple ranulas is 0.2 cases for every 1000 people. The prevalence for plunging ranulas is unknown, but thought to be significantly lower [3]. They usually present in the third decade of life and occur as the result of trauma or infection [3]. A congenital predisposition has been suggested, given their predominance in Maori and Pacific Islanders [3].

On physical examination, plunging ranulas are painless, anterolateral neck masses that do not move with swallowing. Very large plunging ranulas are also termed “giant ranulas” when they extend into the parapharyngeal space, as in this case.

Cross-sectional imaging findings of plunging ranula include a unilocular large water density mass with a smooth capsule, lack of internal septations, and location extrinsic to the submandibular gland. Imaging is used to evaluate the path of extension and for ectopic sublingual glands on the undersurface of the mylohyoid muscle [4]. Two main paths of extension are seen: (a) posterior to the mylohyoid and anterior to the submandibular gland and hyoglossus muscle, or (b) through a dehiscence in the mylohyoid muscle. In the first and more common extension path, communication between the sublingual and submandibular components results in a “tail sign” with smooth tapering anteriorly into the sublingual space [1], as in this case. Magnetic resonance imaging shows a T2-w hyperintense cystic lesion that is low to intermediate intensity on T1-w images with a smooth capsule without internal septations. T1-w images show a low to intermediate intensity [5]. Enhancement of the capsule denotes secondary infection [6]. Ultrasound has been shown to be able to confirm the suspected clinical diagnosis by being able to demonstrate its cystic nature and its anatomic relationship to the myohyoid muscle and culprit sublingual gland [6].

The key differential diagnosis for plunging ranulas on imaging is cystic hygromas. Cystic hygromas are congenital lymphatic malformations that may not present until adulthood. Cystic hygromas can be distinguished by their infiltrative nature with indistinct margins, lobulations, and septations [5]. Cystic hygromas infrequently communicate with the sublingual space, while all plunging ranulas do [5]. Second brachial cleft cysts, like ranulas, are also well circumscribed, homogenous, low density cysts. Second brachial cleft cysts can be discerned by their characteristic location anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle, lateral to carotid space, and posterior to the submandibular glands. Additionally, they can be identified by the presence of a nearly pathognomonic “tail” extending between the internal and external carotid arteries [7]. Dermoid cysts occur in the midline and are thin-walled unilocular masses. They can be definitively identified by a “sack-of-marbles” appearance, with nodular fat coalesced within a fluid matrix [8]. Epidermoid cysts occur off-midline and are fluid-intensity on CT. Occurrence in the sublingual space is difficult to distinguish from plunging ranula, however they are rare and typically present during infancy [8]. Thyroglossal duct cysts are well-circumscribed cysts that can be identified by their anterior midline location, most commonly at the level of the hyoid bone, and their movement with swallowing.

Diagnosis is definitely established with fine-needle aspiration and demonstration of mucus and high amylase content. Imaging is used for confirmation of clinical diagnosis and for surgical planning [9]. The presence of rim-enhancement and/or peripheral fat stranding is suggestive of secondary infection, for which expeditious antibiotic administration and surgical intervention is recommended. Treatment is surgical and involves excision of the sublingual gland in addition to excision and marsupialization of the plunging ranula itself[10]. Recurrence rate is 2% when the sublingual gland is completely excised and can be higher than 50% if complete excision is not achieved. Other surgical complications include temporary or permanent lingual and mandibular nerve damage. [11].

TEACHING POINT

Plunging ranulas are mucus retention pseudocysts that result from an obstructed sublingual gland and are categorized as either simple ranulas, which are confined to the sublingual space, or as plunging ranulas, when they extend into the submandibular space by “plunging” over, or through the mylohyoid muscle. Definite treatment is surgical with removal of the collection and the involved sublingual gland.

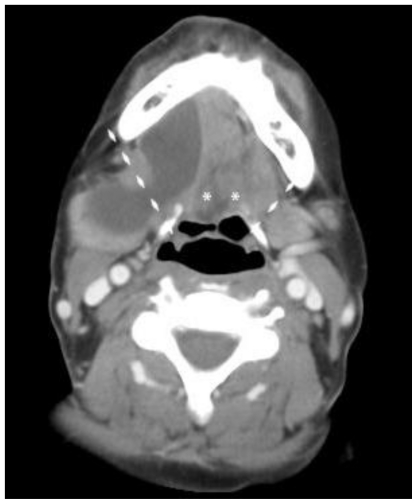

Figure 2.

Initial contrast enhanced axial Computed Tomography - 100 cc of Omnipaque-300 (KVp 120, mA 20 * 3572ms). 44-year-old female with plunging ranula. Slightly inferior slice through the mid-portion of the lesion - shows that the anterior aspect of the lesion is centered in the sublingual space, lateral to the geniohyoid muscle (left *). The contralateral geniohyoid (right *) is also seen. Extension into the sublingual, parapharyngeal, and submandibular spaces is seen. The lesion measures 6.7 × 2.2 × 4.5 cm and is of water-density density. It is non-enhancing, homogenous, smoothly-marginated, and without internal septations.

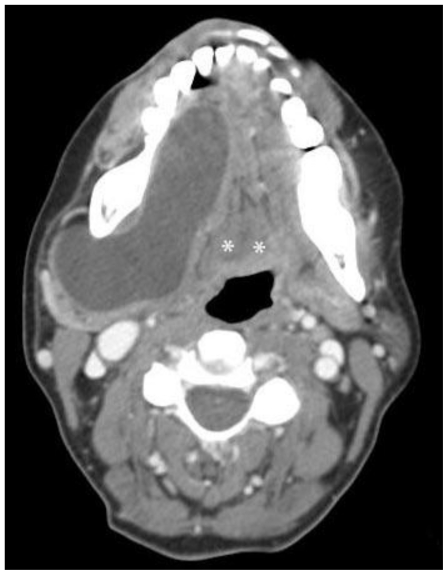

Figure 5.

Follow-up contrast enhanced axial Computed Tomography performed 2 months later - 80 cc of Omnipaque-300 (KVp 120, mA 20 * 3575 ms). 44-year-old female with infected plunging ranula. Slightly more caudal, the mid-portion of the lesion (labeled with *). The mass has unchanged anatomic relationships, but has slightly enlarged and now measures 6.9 × 3.7 × 4.0 cm. Smooth tapering anteriorly into the sublingual space, forming the “tail sign,” is again seen, but better appreciated on stack images. It remains homogenous, smoothly-marginated, and without internal septations. Thick rim-enhancement is now seen (labeled with arrows), consistent with secondary infection. Mass effect with tracheal deviation and compression is worse and there is new right submandibular and cervical reactive lymphadenopathy. The mass was surgically excised and pathologically proven to be a plunging ranula.

Figure 6.

Follow-up contrast enhanced axial Computed Tomography performed 2 months later - 80 cc of Omnipaque-300 (KVp 120, mA 20 * 3575 ms). 44-year-old female with infected plunging ranula. More caudal, at the level of hyoid bone. The mass (labeled with *) has unchanged anatomic relationships, but has slightly enlarged and now measures 6.9 × 3.7 × 4.0 cm. It remains homogenous, smoothly-marginated, and without internal septations. Thick rim-enhancement is now seen, consistent with secondary infection. Mass effect with tracheal deviation and compression is worse and there is new right submandibular and cervical reactive lymphadenopathy. The mass was surgically excised and pathologically proven to be a plunging ranula.

Figure 7.

Follow-up contrast enhanced axial Computed Tomography performed 2 months later - 80 cc of Omnipaque-300 (KVp 120, mA 20 * 3575 ms). 44-year-old female with infected plunging ranula. The image demonstrates the inferior aspect of the lesion. The mass (labeled with *) has unchanged anatomic relationships, but has slightly enlarged and now measures 6.9 × 3.7 × 4.0 cm. It remains homogenous, smoothly-marginated, and without internal septations. Thick rim-enhancement is now seen, consistent with secondary infection. Mass effect with tracheal deviation and compression is worse and there is new right submandibular and cervical reactive lymphadenopathy. The mass was surgically excised and pathologically proven to be a plunging ranula.

Table 1.

Differential diagnoses of cystic masses in the neck.

| Differential Diagnosis | General Characteristics | Ultrasound | CT | MRI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cystic hygroma | Multilocular mass with internal septations and indistinct margins. May have fluid-fluid levels Only rarely communicate with the sublingual space. |

Numerous smooth septa appearing as asymmetrical thin walled cysts. Echogenic areas of lymphatic channels and layering echogenic hemorrhagic fluid. |

Hypoattenuating ill defined multiloculated cystic mass. Increased fluid density when infected. |

T1-w: Low signal, unless containing blood or chyle, fluid-fluid levels T2-w: High signal |

| Second brachial cleft cyst | Most commonly appears anterior to the upper third of the sternocleidomastoid muscle lateral to the carotid space, and posterior to the submandibular gland. Cyst may be unilocular or septated if secondarily infected “Beak sign” with medial extension between the external and internal carotid arteries is pathognomonic | Sharply marginated, round to ovoid, anechoic collection with acoustic enhancement. Small internal echoes from debris. | Well circumscribed, round homogenous, low density cyst with no discernable thin wall Enhancement and wall thickening if infected. |

T1-w: Variable from low to intermediate signal intensity. Increased wall thickeness if prior infection. T2-w: High signal intensity |

| Dermoid/Epidermoid cyst | Lined by a thin stratified squamous epithelium Dermoid cysts occur in the midline, usually at the floor of the mouth, while epidermoid cysts occur off-midline Fluid-fluid levels |

Nodular echogenic masses consistent with “sack-of-marbles” appearance | Low density, non-enhancing mass “Sack of marbles” from coalescence of fat into nodules |

T1-w: Dermoid cysts are variable Epidermoid cysts are hypointense T2-w: Hyperintense Epidermoid cysts demonstrate restricted diffusion |

| Thyroglossal duct cyst | Midline, at or below the hyoid bone Moves with swallowing |

Anechoic mass with thin outer wall, increased through transmission, may have echogenic fluid from proteinaceous content | Thin walled, well circumscribed homogenous cystic collection Rim enhancement with infection |

T1-w: Typically low signal T2-w: Typically high signal |

| Abscess | Variable appearance with rim enhancement and adjacent fat stranding | Hypoechoic well-circumscribed mass with variable hyperechoic debris | Low-density lesion with rim enhancement May contain air |

T1-w: Typically low signal, may be increased depending on protein content T2-w: Typically high signal |

| Lipoma | Encapsulated simple fat containing lesion | Well defined homogenous echogenic mass | Fat density mass (−65 to −100 HU) with thin, smooth enhancing capsule |

T1-w: Hyperintense, drops out on fat suppression T2-w: Intermediate signal |

Table 2.

Summary Table: Overview and statistics of plunging ranulas.

| Etiology | Pseudocystic salivary retention collection from an obstructed sublingual gland that “plunges” by extending inferiorly beyond the free edge of the mylohyoid muscle, or through a dehiscence of the muscle itself, to enter the submandibular space. |

| Incidence | Rare complication of a simple ranula. A simple ranula occurs approximately .2 cases in every 1000 people while the exact frequency of plunging ranulas is unknown. It is more common in Maori and Pacific Island Polynesian populations. |

| Gender Ratio | More prevalent in males with a ratio of 1:0.74 while simple ranulas more common in females with a ratio of 1:1.2 |

| Age Predilection | Most common in the third decade of life |

| Risk Factors | Previous salivary gland infection or trauma. Question of genetic or congenital risk factor given increased prevalence in Maori and Pacific Island Polynesian populations. |

| Treatment | Complete surgical removal of the affected sublingual gland and marsupialization of the plunging ranula |

| Prognosis | Recurrence rate is 2% when the sublingual gland is completely excised and may be higher than 50% if complete excision is not achieved. |

| Findings on Imaging | US – Anechoic encapsulated lesion without internal septations CT - Water density mass, smooth capsule, no septations, and location extrinsic to the submandibular gland. “Tail sign” with smooth tapering anteriorly from the submandibular space into the sublingual space. Enhancement and adjacent fat stranding suggests secondary infection MR- Homogenous T1 hypointensity and T2 hyperintensity, relative to muscle |

| Etiology | Pseudocystic salivary retention collection from an obstructed sublingual gland that “plunges” by extending inferiorly beyond the free edge of the mylohyoid muscle, or through a dehiscence of the muscle itself, to enter the submandibular space. |

| Incidence | Rare complication of a simple ranula. A simple ranula occurs approximately .2 cases in every 1000 people while the exact frequency of plunging ranulas is unknown. It is more common in Maori and Pacific Island Polynesian populations. |

| Gender Ratio | More prevalent in males with a ratio of 1:0.74 while simple ranulas more common in females with a ratio of 1:1.2 |

| Age Predilection | Most common in the third decade of life |

| Risk Factors | Previous salivary gland infection or trauma. Question of genetic or congenital risk factor given increased prevalence in Maori and Pacific Island Polynesian populations. |

| Treatment | Complete surgical removal of the affected sublingual gland and marsupialization of the plunging ranula |

| Prognosis | Recurrence rate is 2% when the sublingual gland is completely excised and may be higher than 50% if complete excision is not achieved. |

| Findings on Imaging | US – Anechoic encapsulated lesion without internal septations CT - Water density mass, smooth capsule, no septations, and location extrinsic to the submandibular gland. “Tail sign” with smooth tapering anteriorly from the submandibular space into the sublingual space. Enhancement and adjacent fat stranding suggests secondary infection MR- Homogenous T1 hypointensity and T2 hyperintensity, relative to muscle |

ABBREVIATIONS

- CT

Computed Tomography

- MRI

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- T1-w

T1-weighted

- T2-w

T2-weighted

REFERENCES

- 1.Coit WE, Harnsberger HR, Osborn AG, Smoker WR, Stevens MH, Lufkin RB. Ranulas and their mimics: CT evaluation. Radiology. 1987 Apr;163(1):211–6. doi: 10.1148/radiology.163.1.3823437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davison MJ, Morton RP, McIvor NP. Plunging Ranula: clinical observations. Head Neck. 1998 Jan;20(1):63–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(199801)20:1<63::aid-hed10>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morton RP, Ahmad Z, Jain P. Plunging ranula: congenital or acquired. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010 Jan;142(1):104–7. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charnoff SK, Carter BL. Plunging Ranula: CT diagnosis. Radiology. 1986 Feb;158(2):467–8. doi: 10.1148/radiology.158.2.3941874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macdonald AJ, Salzman KL, Harnsberger HR. Giant ranula of the neck: differentiation from cystic hygroma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003 Apr;24(4):757–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jain P, Jain R, Morton RP, Ahmad Z. Plunging ranulas: high-resolution ultrasound for diagnosis and surgical management. Eur Radiol. 2010 Jun;20(6):1442–9. doi: 10.1007/s00330-009-1666-1. Epub 2009 Nov. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lanham PD, Wushensky C. Second brachial cleft cyst mimic: case report. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005 Aug;26(7):1862–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koeller KK, Alamo L, Adair CF, Smirniotopoulos JG. Congenital cystic masses of the neck: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1999 Jan-Feb;19(1):121–46. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.19.1.g99ja06121. quiz 152–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ichimura K, Ohta Y, Tayama N. Surgical management of the plunging ranula: a review of seven cases. J Laryngol Otol. 1996 Jun;110(6):554–6. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100134243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrison JD. Modern management and pathophysiology of ranula: literature review. Head Neck. 2010 Oct;32(10):1310–20. doi: 10.1002/hed.21326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel MR, Deal AM, Shockley WW. Oral and plunging ranulas: What is the most effective treatment. Laryngoscope. 2009 Aug;119(8):1501–9. doi: 10.1002/lary.20291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]