Abstract

We present a case of spontaneous pneumomediastinum (SPM) associated with sex. A 22-year-old lesbian with a history of asthma, cigarette and illicit drug smoking was diagnosed with a SPM after developing chest pain and dyspnoea in the context of performing oral sex. The main finding was subcutaneous emphysema involving the neck. SPM is an important differential diagnosis for chest pain in young people. It is a benign condition and diagnosis mainly limited to chest X-ray with increased incidence in asthmatics, smokers and drug addicts.

Keywords: Pneumomediastinum, dysphagia, dysphonia, Hamman’s sign, CTPA, Boerhaave’s Syndrome

CASE REPORT

A 22 year old woman presented to Emergency complaining of severe pleuritic, retrosternal chest pain. She had associated dyspnoea but no cough, wheeze, sputum or haemoptysis and smoked 15 cigarettes per day. There was no fever, sweats or calf pain. She did not take the oral contraceptive pill, had undertaken only interstate air travel during the preceding week, but had a family history of deep vein thrombosis (DVT). She used no medication but admitted to occasional marijuana use and smoking ‘ice’ (crystal methamphetamine hydrochloride) the preceding evening. Past history included asthma. In addition, she also had right throat pain; although no dysphagia, odynophagia or dysphonia, and no history of excessive vomiting or coughing.

On further questioning, it was revealed the onset of pain occurred three hours earlier when the patient was engaged in oral sex with her lesbian partner. She described holding her breath for prolonged periods, at one point feeling an initial sharp pain. This pain then returned 20 minutes later, intensified, and remained constant. On examination she was afebrile and haemodynamically stable, with a respiratory rate of 18 breaths/minute and oxygen saturation of 98% on room air. Subcutaneous emphysema involving the left side of her neck was the main finding, based on palpable and audible crepitations. Respiratory examination was unremarkable other than poor inspiratory effort, and there was no Hamman’s sign or rib pain elicited. There was no evidence of DVT. Electrocardiography was normal. Blood tests showed an elevated white cell count (WCC) of 18.6 × 109/L (Ref Range 4.0–11.0) (neut 14.9, lymph 2.3) and D-dimer of 0.62 (N<0.5), but were otherwise normal. C- reactive protein was normal (N<5). Chest X-ray (CXR) showed evidence of pneumomediastinum and clear lung fields (Figure-1). A computed tomography pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) revealed extensive pneumomediastinum, with evidence of air dissecting tissue plane both around the mediastinal structures and extending into the neck. The lumen of the oesophagus and trachea appeared intact throughout and there was no evidence of pulmonary embolus (PE) (Figure-2).

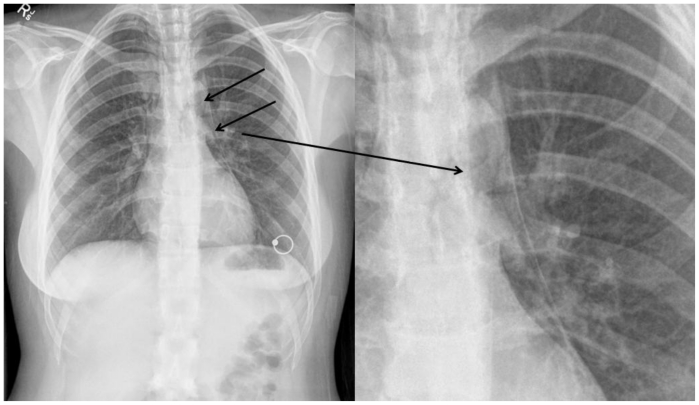

Figure 1.

Initial chest radiograph (PA upright view) of a 22 years old female showing feature of pneumomediastinum (arrows) which is presence of air in the mediastinum and incidental nipple ring. The lung fields are clear. The magnified view on the left shows a clear demarcation line exhibiting the presence of the air in the diaphragm.

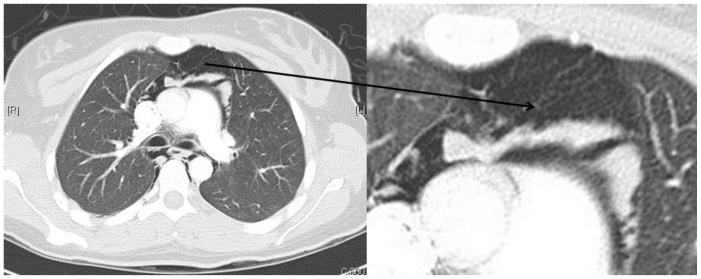

Figure 2.

Initial CTPA image of a 22 year old female with pneumomediastinum showing the presence of air dissecting tissue planes in mediastinum (pointing arrow). CTPA was performed with Siemen’s somatom sensation 64 slices, 180 mAs and 120 kV energy, plane was axial; slice thickness was 1.5 × 1.5 mm with 70mls ultravist 370 contrast used. The lumen of the oesophagus and trachea appeared intact throughout and there was no evidence of pulmonary embolus. The magnified image on the left shows the same findings.

This patient was observed for 24 hours. Management included oral analgesia, rest, and advice to refrain from exertion, exercise, smoking and scuba diving. The pneumomediastinum on CXR and subcutaneous emphysema was resolving 3 days later (Figure-3) as an outpatient and had completely resolved by review at 3 weeks (Figure-4).

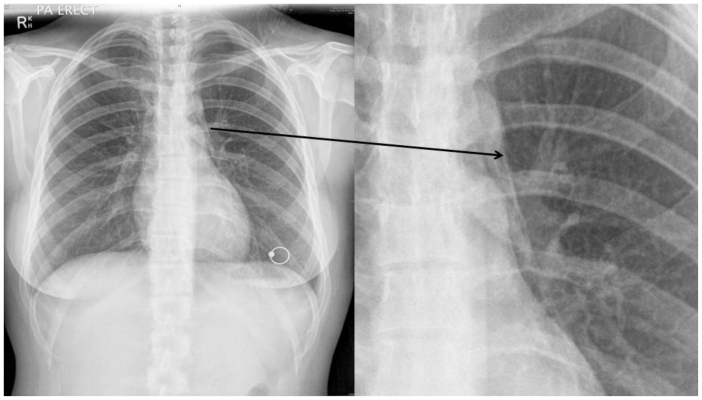

Figure 3.

Day-3 chest radiograph (PA upright view) shows the resolving pneumomediastinum (arrow) where the size of pneumomediastinum can be visualised to be significantly reduced as compared to Figure-1. For the ease of the reader, view has been magnified to show the resolving pneumomediastinum.

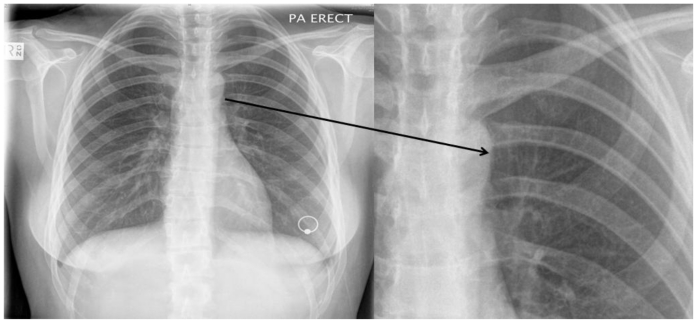

Figure 4.

Chest radiograph (PA upright view) at 3 weeks following presentation, showing complete resolution of the pneumomediastinum (arrow) where no pneumomediastinum can be visualised.

DISCUSSION

Spontaneous pneumomediastinum (SPM) (the presence of air in the mediastinum for which no cause or disease process is found), is a rare presentation to emergency departments with an incidence reported between 1 in 29,670 (1) and 44,511 (2). It was described by Hamman (3) where he identified a crackling or crunching sound associated with the heart beat (Hamman’s sign), but studies have shown its presence to be variable. It has been shown to have an increased incidence in asthmatics, smokers and users of inhaled illicit drugs, and to be associated with actions that involve valsalva such as coughing, sneezing, defecating, birthing and vomiting. (2) Our patient most likely suffered a SPM after prolonged and strenuous valsalva, in addition to a background of asthma, smoking and methamphetamine use.

More than 75% of reported cases of SPM are males with a mean age of 20 years2. Symptoms include retrosternal chest pain and dyspnoea, and less commonly neck pain, dysphonia, odynophagia or dysphagia, and reflect the dissection of peribronchiole, mediastinal and neck tissue planes by pressurised air secondary to alveolar rupture (4). Patients often present with normal vital signs and a not uncommon finding on examination is subcutaneous emphysema, usually involving the neck2.

The differential diagnosis is broad and includes all the usual cardiac, pulmonary, oesophageal and musculoskeletal suspects for pleuritic chest pain and dyspnoea. Moreover, the etiology of pneumomediastinum is varied and penetrating or blunt thoracic trauma, pulmonary infection with gas producing organisms and oesophageal rupture (Boerhaave’s Syndrome) are recognised alternative causes. Boerrhave syndrome was not suspected in this case as ‘the classic history is of dysphagia, odynophagia, fever, leucocytosis and pleural effusion with or without shock in a person who has been wretching’, which was mentioned. It did not fit with the history; these patients are usually very sick. Our patient remained stable and was not shocked. Thus, contrast swallow and oseophagoscopy were not performed. A good history and examination, and routine investigations are mandatory discriminatory precursors. CT chest with IV contrast is also recommended, despite the well documented accuracy of combined posteroanterior and lateral CXRs alone (2,5–8). Firstly, because Kaneki et al showed that the diagnosis may be unclear in a significant 30% of cases where the leak is posterior to the mediastinum (9). More definitively however, the low cost, simplicity and sensitivity of CT today makes it a cost effective and judicious means of excluding alternate differentials, and causes of pneumomediastinum such as oesophageal perforation which may present similarly, though the classic history is of dysphagia, odynophagia, fever, leucocytosis and pleural effusion with or without shock in a person who has been wretching. Where oesophageal perforation is suspected contrast enhanced swallow and/or oesophagoscopy is indicated. CTPA was performed in this case due to the leucocytosis and enabled us to rule out PE. Though the largest published case series found an elevated WCC and/or neutrophilia in 41.7% (2) of cases, it is suggested that a leucocytosis especially if associated with a fever should raise concern about a more serious alternate diagnoses or cause for pneumomediastinum.

SPM is a benign, self-limiting condition and complications are extremely rare. Management is conservative and includes bed rest, analgesia, reassurance and due diligence as to the theoretical possibility of viscus rupture such as tension pneumomediastinum or pneumothorax. That said, such complications have not been documented in the literature. Recurrence too is rare (5,8). SPM is an important consideration in young people with chest pain and shows a rising incidence in drug users (6). A list of incidental associations includes inflation of party balloons (10), playing a trombone (11), Xiao-Lin Temple Boxing vocal exercise (12), vaginal delivery (13) and a ‘karaoke related incident’ (14). To our knowledge, there is one published case relating to sex, involving homosexual intercourse in a 21 year old male student (15).

TEACHING POINT

Spontaneous pneumomediastinum (SPM) is an important differential of chest pain in young people and CT chest with IV contrast is an important investigative tool SPM is a benign condition which shows increased incidence in asthma, smoking, and drug use and is managed conservatively.

ABBREVIATIONS

- SPM

spontaneous pneumomediastinum

- DVT

deep vein thrombosis

- WCC

white cell count

- CXR

Chest X-ray

- PE

pulmonary embolus

- CTPA

computed tomography pulmonary angiogram

REFERENCES

- 1.Newcomb AE, Clarke P. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum. A benign curiosity or a significant problem? Chest. 2005 Nov;128(5):3298–302. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.5.3298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macia I, Moya J, Ramos R, et al. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: 41 cases. European Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery. 2007 Jun;31(6):1110–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamman L. Spontaneous mediastinal emphysema. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1939;64:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macklin MT, Macklin CC. Malignant interstitial emphysema of the lungs and mediastinum as an important occult complication in many respiratory diseases and other conditions: an interpretation of the clinical literature in the light of laboratory experiment. Medicine. 1944;23:281–358. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerazounis M, Athanassiadi K, Kalantzi N, Moustardas M. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: a rare benign entity. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003 Sep;126(3):774–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(03)00124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koullias GJ, Korkolis DP, Wang XJ, Hammond GL. Current assessment and management of spontaneous pneumomediastinum: experience in 24 adult patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004 May;25(5):852–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freixinet J, García F, Rodríguez PM, Santana NB, Quintero CO, Hussein M. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum long-term follow up. Respir Med. 2005 Sep;99(9):1160–3. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abolnik I, Lossos IS, Breuer R. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: a report of 25 cases. Chest. 1991 Jul;100(1):93–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.100.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaneki T, Kubo K, Kawashima A, Koizumi T, Sekiguchi M, Sone S. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum in 33 patients: Yield of chest computed tomography for the diagnosis of the mild type. Respiration. 2000;67(4):408–11. doi: 10.1159/000029539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mumford AD, Ashkan K, Elborn S. Clinically significant barotrauma after inflation of party balloons. BMJ. 1996 Dec-28;313(7072):1619. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7072.1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ho S, Takada Y, Tanaka A, et al. A case of spontaneous pneumomediastinum in a trombonist. Kokyu To Junkan. 1989;37(12):1359–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoneyama H, Matsushima T, Nakamura J, et al. Two cases of spontaneous pneumomediastinum due to Xiao-Lin Temple Boxing vocal evercise. Nippon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshui. 1990;28(1):151–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sutherland F, Ho S, Campanella C. Pneumomediastinum during spontaneous vaginal delivery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002 Jan;73(1):314–5. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)02729-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Togashi K, Hosaka Y. Primary spontaneous pneumomediastinum. Kyobu Geka. 2007;60(13):1163–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Packham CJ, Stevenson GC, Hadley S. Pneumomediastinum during sexual intercourse. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984 Apr 21;288(6425):1196–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.288.6425.1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iyer VN, Joshi AY, Ryu JH. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: analysis of 62 consecutive adult patients. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009 May;84(5):417–21. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60560-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zylak CM, Standen JR, Barnes GR, Zylak CJ. Pneumomediastinum revisited. Radiographics. 2000 2001 Jul-Aug;20(4):1043–57. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.4.g00jl131043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bejvan SM, Godwin JD. Pneumomediastinum: old signs and new signs. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996 May;166(5):1041–8. doi: 10.2214/ajr.166.5.8615238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caceres M, Ali SZ, Braud R, Weiman D, Garrett HE., Jr Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: a comparative study and review of the literature. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008 Sep;86(3):962–6. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.04.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]