Abstract

We report a case of postpartum hemorrhage due to adherent placenta. A 28 year old primiparous woman who underwent manual removal of placenta for primary postpartum haemorrhage soon after delivery was referred to our Institute on her third postnatal day because of persistent tachycardia and low grade fever. Placenta accreta was suspected on initial ultrasonographic examination. MRI examination confirmed the diagnosis of placenta accreta in few areas and revealed increta in other areas. On expectant management she developed genital tract sepsis and hence she was treated with intravenous Methotrexate after controlling infection with appropriate antibiotics. Doppler Imaging showed decreased blood flow to the placental mass and increased echogenecity on gray scale USG after Methotrexate administration. She expelled the whole placental mass on 35th postnatal day and MRI performed the next day showed empty uterine cavity. Morbid adhesion of placenta should be suspected even in primiparous women without any risk factors when there is history of post-partum hemorrhage. MRI is the best modality for evaluation of adherent placenta.

Keywords: Manual removal of placenta, Placenta accreta & increta, MRI, Methotrexate

CASE REPORT

A 28 year old primiparous woman was referred to our Emergency department as a case of traumatic Postpartum hemorrhage following low-mid cavity forceps undertaken 2 days ago at a private nursing home. The placenta was retained for >1 hr and she had postpartum hemorrhage, hence manual removal of placenta was done under general anaesthesia. The placenta was removed in piece meal. There were large vaginal lacerations on the anterior and right lateral vaginal wall and these were sutured with Vicryl. She received oxytocics and 3 units of blood transfusion. She had persistent tachycardia and developed low grade fever on the next day and had minimal vaginal bleeding and hence she was referred to our Institution,

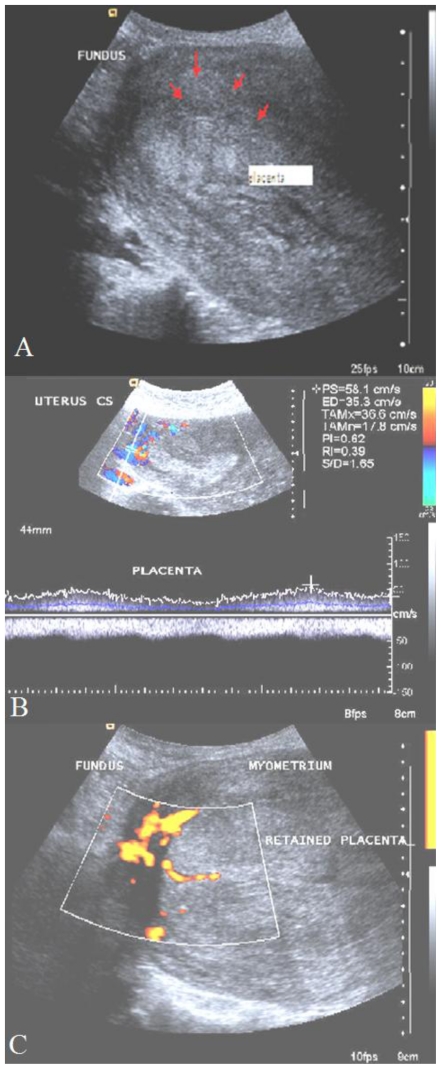

When the patient presented to us, on physical examination, she was anxious, afebrile and had mild palor. Her pulse rate was 120 bpm regular and blood Pressure was 124/90 mm Hg. On abdominal examination, uterus was 24 weeks size, well contracted but tender. On speculum examination, sutured episiotomy wound and anterior and right vaginal wall lacerations were seen and there was no active bleeding from these areas. There was minimal bleeding through the Os and cervix was patulous. On vaginal examination, uterus was 24 weeks size and no forniceal masses were detected. At this time preliminary diagnosis was anemia secondary to traumatic postpartum hemorrhage. Given the piecemeal removal of placenta, a Gray scale trans - abdominal sonogram (TAS) was performed to rule out the possibility of retained products of conception. TAS showed a puerperal uterus with a 7×8 cm mass on the anterior wall and fundus with similar echogenicity to that of myometrium (Fig. 1A). The differential diagnosis included a sub mucuosal fibroid versus retained products of conception and 400 μg Misoprost was administered per rectum to assist in expulsion of any possible retained products of conception. No products were expelled in 24 hours and a repeat TAS was performed. The mass demonstrated no capsule and there was no distinct demarcation between the mass and the myometrium (Fig. 1A). To evaluate for adherent placenta, Color Doppler and Power Doppler examination was performed (Siemens Antares, Germany with a 3–5 MHz multifrequency probe). Colour Doppler (Fig. 1B) on sixth postnatal day revealed an area of blood flow in to the myometrium at the antero-superior aspect of the placental mass which was further confirmed by power Doppler (Fig. 1C). Placenta accreta was suspected and an MRI was recommended to confirm this diagnosis and further characterize the findings. It was decided to manage her expectantly.

Figure 1.

28 year old primipara third post natal day - with Postpartum haemorrhage. Transabdominal sonography prior to methotrexate administration. 1A: Ultrasonography; longitudinal section of uterus showing placental invasion in to the myometrium (red arrows). The echogenecity of placental invasion is almost similar to that of myometrium. (Siemens Antares -3–5 mega Hz curvilinear transducer) 1B showing persistent increased blood flow at the fundus with the retained placenta. (Siemens Antares Color Doppler with 3–5 mega Hz) 1C: Power-Doppler showing blood flow at the fundus of uterus and placental mass (Siemens Antares 3–5 MHz convex probe)

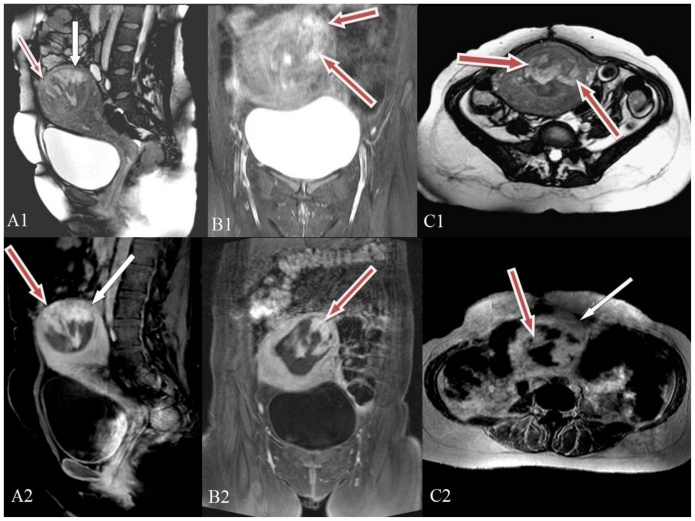

MRI of the pelvis was performed on the twelfth post-natal day (Fig. 2) showing the hyperintense placenta invading the myometrium almost up to the serosa at the fundus of the uterus sparing the deep myometrial layer (invading more than 50% of the myometrial thickness) consistent with increta. Post contrast MRI images demonstrated placental tissue at the fundus and in the anterior wall of uterus with high signal intensity. The placenta showed intense contrast enhancement infiltrating in to the myometrium with adjacent myometrial thinning. The serosal surface appeared intact and there was no abnormality in the surrounding soft tissue. The findings confirmed the diagnosis of placenta accreta with few areas of focal increta on the anterior wall and fundus reaching up to the serosa of uterus but not beyond it.

Figure 2.

28 year old primipara with adherent placenta - 12th postnatal day.

2A1: pre contrast T2 weighted MRI sagittal image (TR 5464 TE 44; 1.5 Tesla Siemens Avanto-TIM machine, Germany, using pelvic phased array coil; matrix 320×640 FOV 26×26). Red arrow shows the hyperintense placenta invading the myometrium almost up to the serosa at this part of the uterus. White arrow shows the plane of placenta at myometrium sparing the deep myometrial layer corresponding to accreta. 2B1: pre contrast T2 weighted tirm MRI coronal image (TR 7911 TE 44 TI 160; Siemens Avanto 1.5 Tesla MRI). Red arrows point to the hyperintense lesion corresponding to the retained placental tissue. The hyperintense placental tissue is invading more than 50% of the myometrial thickness consistent with increta. 2C1: Pre contrast T2 weighted TRUFI MRI axial image (TR 2.82 TE 1.2; Siemens Avanto 1.5 Tesla MRI). Red arrows point to the hyperintense lesion corresponding to the retained placental tissue.

2A2: Post-natal day- post Gadolinium contrast venous phase T1 weighted fat suppressed MRI sagittal image (TR 319 TE 2.5; Siemens Avanto 1.5 Tesla MRI; 8 ml of Gadolinium). Red arrows point to the irregular heterogenous intense enhancement of the placenta and its invasion through myometrium upto the serosa in the fundus of the uterus. White arrow points to the hyperintense placenta abutting the superficial layer of myometrium. 2B2: Post Gadolinium venous phase T1 weighted fat suppressed MRI coronal image (TR 3.2 TE 1.1; Siemens Avanto 1.5 Tesla MRI). Red arrow points to the intensely enhancing lesion corresponding to the retained placental tissue. 2C2: Post Gadolinium venous phase T1 weighted MRI axial image (TR 270 TE 4.76; Siemens Avanto 1.5 Tesla MRI). Red arrow points to the intensely enhancing lesion corresponding to the retained placental tissue and white arrow to the lesser intense surrounding myometrium.

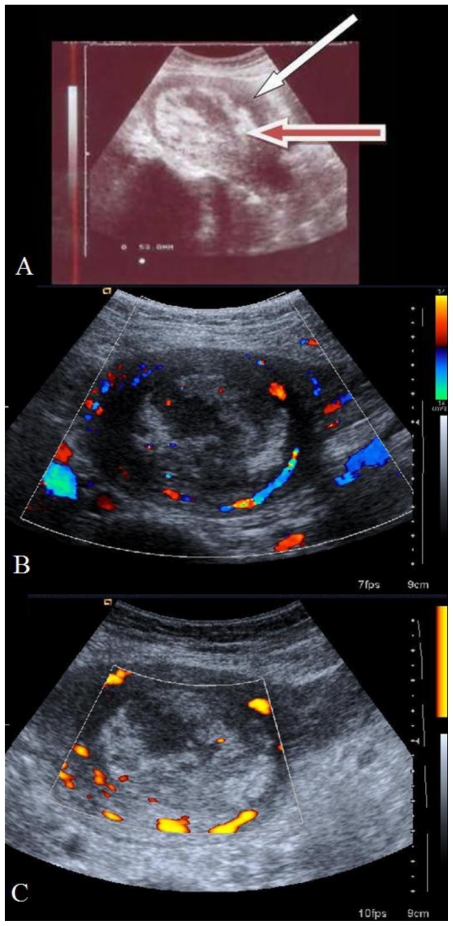

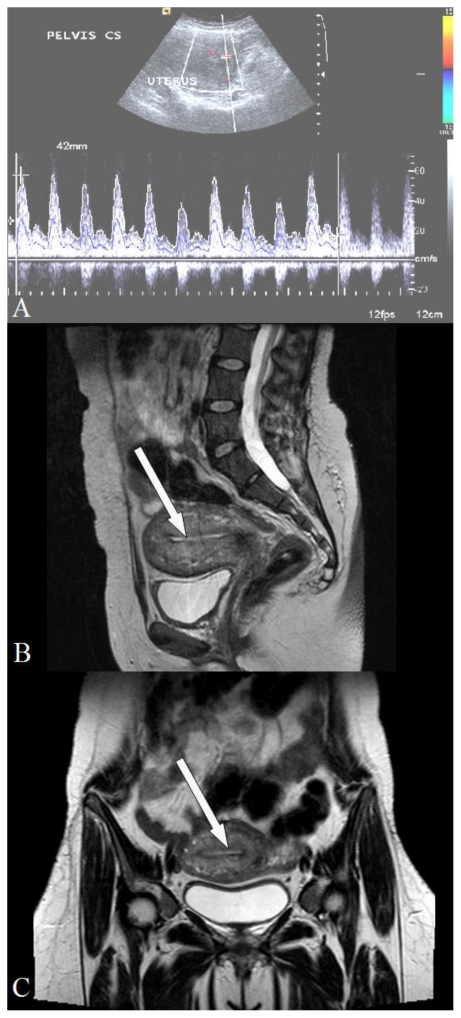

Her complete blood count profile showed Hb of 7.8 gm% and total leucocyte count of 13,900/mm3 with a differential count of 84% neutrophils. Platelet count was 221,000 mm3, renal function tests and liver function tests were normal. Cervical swab report showed growth of Acenetobacter boumani which was sensitive Cifrofloxacin and Amikacin. She received injection of Ciprofloxacin and Amikacin intravenously for seven days as she was febrile while being on only oral Ciprofloxacin. Hence she was counselled for medical management on 13th post-natal day and injection Methotrexate 1mg/Kg was given intravenously on Day 1,3,5,7,9 and folic acid on Day 2,4,6,8,10. Breast feeding was replaced by formula feeding during this one week. Repeat cervical swab culture showed normal flora and she was discharged on 21st post-natal day after performing USG which showed increased echogenecity of placenta (Fig. 3A) and decreased blood flow on Color Doppler (Fig. 3B) and Power Doppler (Fig. 3C). along with recommendations for follow-up Color Doppler examination to see the vascularity. She expelled a mass on 35th post-natal day and came for follow up on the next day. TAS (Fig. 4A) revealed an involuted uterus with empty cavity and normal uterine blood flow. The T2 weighted sagittal and Coronal images of MRI performed on the same day (Fig. 4B & Fig. 4C) showed an empty uterine cavity with normal signal intensities in the endo-myometrium.

Figure 3.

28 year old primipara with placenta increta after methotrexate administration, 19th post-natal day - transabdominal sonography. 3A: Sagittal section (Siemens-Antares; 3.5MHz probe) showing increased echogenicity of placenta. Red arrow shows echogenic placental mass and white arrow points to the myometrium. 3B: Color Doppler (Siemens Antares; 3–5 MHz probe) showing decreased blood flow to the placenta (cross section). 3C: Power Doppler (Siemens Antares; 3–5 MHz probe) showing reduced blood flow to the echogenic placental mass

Figure 4.

28 year old primipara with placenta increta transabdominal songhraphy after expulsion of placenta (36th post-natal day). 4A: Pulsed Doppler shows normal blood flow in the uterus (Siemens Antares; 3–5 MHz probe). 4B: T2 weighted MRI sagittal image (TR 7210 TE 95; Siemens Avanto 1.5 Tesla MRI). White arrow points to the empty uterine cavity. 4C: T2 weighted MRI coronal image (TR 4181 TE 109; Siemens Avanto 1.5 Tesla MRI). White arrow points to the empty uterine cavity

DISCUSSION

Adherent placenta is one of the important causes of post-partum hemorrhage. The extent of adherence and invasion varies from superficial (accreta), into the myometrium (Increta), and through the myometrium to breach the serosa or beyond (percreta) [1]. When this condition is not anticipated and attempts are made to deliver the placenta there can be catastrophic hemorrhage resulting in maternal mortality. Though the mortality due to placenta accreta has fallen from the early 20th century, the incidence of adherent placenta has increased from 0.025% in 1970’s to 0.04% in 1990’s [2]. The reduction in mortality is mainly because of early diagnosis and changing trends in management especially expectant and medical methods with the availability of more sophisticated radiological investigations. However a mortality rate of 7% was reported due to placenta percreta in a series of adherent placenta [3].

This increased incidence of placenta accreta is attributed to a rise in the rate of caesarean sections during the recent years [1,2]. Other risk factors are placenta praevia, previous myomectomy, Asherman’s syndrome, submucosal fibroids, and maternal age more than 35 years [4]. There have been reports of placenta accreta in the absence of risk factors as reported by Gielchinsky and collegues [5]. One such case who was referred to our Institute as post-partum haemorrhage is reported here. The incidence of placenta accreta is currently (2008) approximately 1 in 534 deliveries increased from 1per 7000 deliveries in the 1970’s [6].. Placental invasion has been visualised by various imaging techniques including prenatal sonography. But this is not always done as this condition is not given much attention due to its low incidence [3]. Loss of retro placental hypoechoeic area and presence of numerous vascular lacunae within the placental substance are the two important findings that can be made out by USG which suggest the presence of adherent placenta. Other findings reported are bulging of the placenta in to the bladder when it is in the lower uterine segment, myometrial thinning and irregularly shaped placental lacunae [7,8]. Invasion into the myometrium is difficult to judge by gray-scale sonography except when the condition involves the major part of the placenta. Color or Power Doppler imaging is another modality in which extension of vascularity from the placental bed can be visualised and evaluated [5]. In this case, Colour Doppler showed the persistence of blood flow to the placenta before methotrexate administration and decreased blood flow after the administration of methotrexate. To visualise vascularisation, 3D angiographic imaging was used to assess the vascularisation index/vascularisation flow index in the postpartum management of placenta previa accreta left in-situ. Some authors performed dilatation and curettage for removal of placental mass when the vascularisation index was minimal in a case of Placenta previa accreta undergoing conservative management [8].

The diagnosis of adherent placenta was often made during the manual removal of placenta [9]. However the patient we report underwent delivery at an outside Institution and it is unclear this diagnosis was considered during the piecemeal removal of the placenta. On USG, on the third postpartum day the part of the placenta retained in the uterus was seen as a mass with same echogenicity as that of the myometrium which made us think of the possibility of a submucosal fibroid. But on Color Doppler the vascularity and the echogenicity of the mass was found to invade few millimetres of the myometrium. However we found MRI to be an excellent tool in diagnosing the retained placental tissue and its degree of invasion in to the myometrium. The MRI appearance of the present case was consistent with the findings of Rahman A and colleagues who reported on the MRI appearances of Placenta pre and post chemotherapy in which the placenta appeared as heterogeneous but predominantly bright signal intensity on T2 W imaging [10]. The placenta in the present case became more echogenic on USG and was delineated from the myometrium after chemotherapy. There are no studies to describe the sensitivity, specificity of MRI in diagnosing the various types of adherent placenta and only a few case reports are available which state that MRI to be a better tool than USG because MRI offers multiplanar capability and excellent soft tissue resolution and it is not operator dependent [10]. The differential diagnosis on USG or MRI when there is no history of piecemeal removal of placenta or retained placenta, include a submucosal fibroid or fibroid polyp, adenomyoma, tuberculous or malignant infiltration of myometrium.

As 20 % of women with placenta accreta are primiparous [9], it is essential to preserve the future fertility of women. Expectant management and medical management play a great role in this aspect. When there is no hemorrhage and infection placenta left in situ can be followed by Color/Power Doppler for cessation/regression of blood flow into the myometrial component and attempts can be made after that to evacuate/remove the placenta. This approach takes as long as 4 months time as reported by Most OL and collegues [8] and is not a satisfying and cost-effective modality for the patient as well as for the Obstetrician. Medical management employing methotrexate was described first by Arulkumaran and colleagues in 1986 [11] and subsequently many reports appeared in literature. Methotrexate, an antimetabolite causes death of the trophoblastic cells and also inhibits cell proliferation by inhibiting the enzyme dihydrofolate reductase. Once the trophoblasts degenerate they no longer anchor to the myometrium and get expelled with uterine contraction. We initially planned to treat conservatively because she was breast feeding and there was no active bleeding, but as the cervical swab culture revealed infection, we started specific antibiotics and then switched over to medical management and achieved success in 2 weeks time when she passed a mass of placental tissue without any further haemorrhage or infection. In patients where Methotrexate is contraindicated or those who are sensitive to Methotrexate uterus can still be conserved by undertaking uterine artery embolisation leaving the placenta in situ [12]. This requires expertise and an interventional radiologist who was not available in our Institute.

TEACHING POINT

Morbid adhesion of placenta should be suspected even in women without any risk factors when there is postpartum hemorrhage and the same should xbe ruled by performing an immediate Ultrasonogram. MRI is the best modality for confirmation of placenta accreta and increta. Medical management with methotrexate should be preferred over expectant management when there are no contraindications. This is essential to preserve the uterus for future fertility.

Table 1.

Summary table for adherent placenta

| Etiology: | Absence of decidua basalis or imperfect development of Nitabuch layer |

| Incidence: | 1 in 533 deliveries (2005) |

| Age predilection: | Maternal age of 35 or older-3.2 fold risk |

| Risk factors: | Placenta praevia; prior caesarean section; prior curettage; grandmultiparity, previous myomectomy, Asherman’s syndrome, submucosal fibroids, and maternal age more than 35 years. |

| Treatment: | Immediate blood replacement for PPH and Hysterectomy if shock persisting; Uterine artery or Internal iliac artery ligation: arterial embolisation Medical management in stable cases Expectant management in selected cases |

| Prognosis: | Hysterectomy reduces maternal mortality Prognosis good in selected cases with conservative/expectant management to preserve future fertility Poor prognostic factors are Hemorrhagic shock and delay in diagnosis. |

Table 2.

Differential diagnoses table for adherent placenta

| Modality | Adherent Placenta | Submucosal fibroid | Leiomyo sarcoma | Invasive mole | Placental site trophoblastic tumour | Endometrial carcinoma |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| CT |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MRIT1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MRI T2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Contrast enhancement MRI |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MRI DWI |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Scintigraphy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| PET |

|

|

|

|

|

|

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Dr. John Davis Akkara, Internist, for helping in preparation of stack of images

ABBREVIATIONS

- USG

Ultrasonogram

- MRI

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- PPH

Post-partum haemorrhage

- GA

General anaesthesia

- RS

Respiratory System

- CVS

Cardiovascular System

- TAS

Transabdominal Sonogram

- Hb

Haemoglobin

- RFT

Renal function tests

- LFT

Liver function tests

- T

Tablet

- T2W

T2 weighted

REFERENCES

- 1.Thia EW, Tan Lay KOk, Devendra K, Tze-Tein Yong, Hak-Koon Tan, Tew-Hong Ho. Lessons learnt from two women with morbidly Adherent Placentas and review of Literature. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2007;36:298–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller DA, Chollet JA, Goodwin TM. Clinical risk factors for placenta previa, placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177:210–214. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70463-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Brien JM, Barton JR, Donaldson ES. The management of Placenta percreta: Conservative and operative strategies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1632–1638. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Committee on Obstetric practice. ACOG committee opinion. Placenta Accreta Number 266. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2002;77:77–78. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(02)80003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gielchinsky Y, Rojansky N, Fasouliotis SJ, Ezra Y. Placenta accreta : Summary of 10 years. A Survey of 310 cases. Placenta. 2002;23:210–214. doi: 10.1053/plac.2001.0764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu S, Kocherginsky M, Ju Hibbard. Abnormal placentation: Twenty year Analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1458–1461. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.12.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breen JL, Neubecker R, Gregori CA, Franklin JE., Jr Placenta accrete, increta and percreta: a survey of 40 cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1977;49:43–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Most OL, Singer T, Buterman I, Monteagudo A, Timor-Tritsch IE. Post-partum management of Placenta Previa Accreta left in Situ. Role of 3-Dimensional Angiography. J Ultrasound Med. 2008;27:1375–1380. doi: 10.7863/jum.2008.27.9.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zaki MS, Bahar AM, Ali ME, Alibar HA, Gerais MA. Risk factors and morbidity in patients with placenta previa accreta compared to placenta previa non-accreta. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1998;77:381–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rahman A, Pye P, Phillips K, Tumbli LW. MRI appearance of placenta accreta pre and post chemotherapy. Clinical Radiology Extra. 2005;60:65–67. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arulkumaram S, Ng CS, Ingemarsson, Rathnam SS. Medical management of placenta accreta with methotrexate. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1986;65:285–286. doi: 10.3109/00016348609155187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tong SYP, Tay KH, Kwek YCK. Conservative management of Placenta accreta: review of three cases. Singapore Med J. 2008;49( 6):156–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]