Abstract

Malignant transformation is a rare complication of endometriosis. MR criteria for diagnosis include the presence of soft-tissue components, enhancement after contrast material administration in an endometriotic cyst. We present the multidetector CT and MR imaging findings in a case of an incidentally found endometrioid adenocarcinoma in a left-sided ovarian endometrioma, occurring in a 30-year old woman. MR imaging enabled the correct preoperative characterization of the lesion, by depicting a soft-tissue element, with strong and early enhancement after gadolinium administration. The same area had high signal intensity on diffusion-weighted images and low apparent diffusion coefficient values due to restricted diffusion, findings also strongly suggestive of malignancy.

Keywords: endometriosis, endometriotic cyst, carcinoma, imaging, multidetector CT, magnetic resonance

CASE REPORT

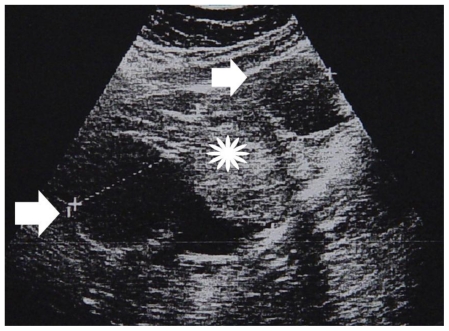

A 30-year old multiparous woman was referred to the Gynecology clinic, for a complex left adnexal mass, discovered incidentally during a sonographic examination (Figure 1). Cancer antigen CA 125 and CA 19-9 levels were elevated: 130 U/ml (normal values < 35 U/ml) and 43 U/ml (normal values < 39 U/ml), respectively).

Figure 1.

30-year old woman with left endometrioid adenocarcinoma developed in a pre-existing ovarian endometrioma. Sagittal gray-scale sonographic scan shows a large, heterogeneous pelvic mass (cursors), with cystic parts (arrows) and solid echogenic loculi (asterisk) (Parameters: probe: transabdominal; frequency: 4 MHz).

Imaging findings

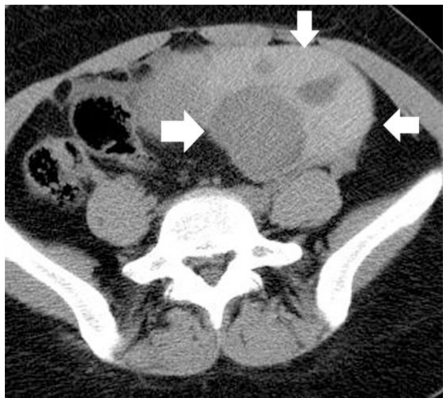

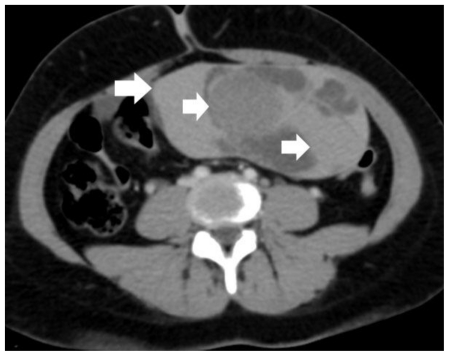

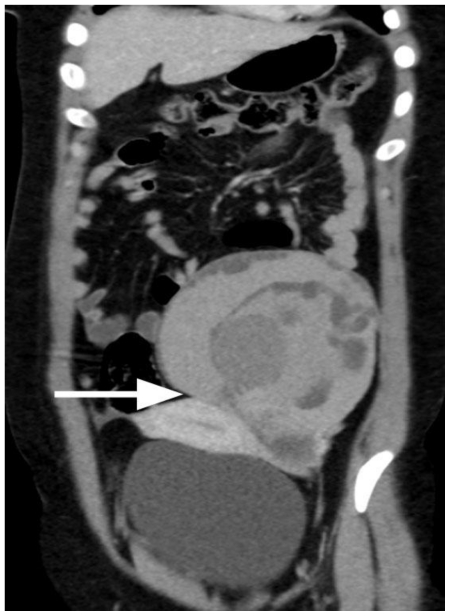

Multidetector CT (MDCT) examination of the abdomen was performed on a 16-row CT scanner (Mx8000 ID, Philips). The protocol included unenhanced CT scanning of the pelvis, using a detector collimation of 16 × 1.5 mm, followed by enhanced CT of the abdomen during the portal phase (scan delay: 70 sec), after the i.v. administration of iodinated contrast material (Visipaque, GE Healthcare) with a detector collimation of 16 × 0.75 mm. A large, multicystic left adnexal mass was revealed, composed mainly of hyperdense parts (CT density range: 45–85 HU), which were attributed to the presence of hemorrhagic content (Figure 2). No obvious lesion enhancement was detected (Figure 3, 4). Neither ascites nor lymphadenopathy was seen. Based on the MDCT findings, no obvious signs of malignancy were found.

Figure 2.

30-year old woman with left endometrioid adenocarcinoma developed within a pre-existing ovarian endometrioma. Transverse unenhanced MDCT image depicts a multicystic left adnexal mass lesion, predominantly with hyperdense components (arrows). The CT density ranged from 45 HU to 85 HU, suggestive of acute hemorrhagic content. (Parameters: 16-row CT scanner; mAs: 130; kV: 120; detector collimation: 16 × 1.5 mm; slice thickness: 5 mm).

Figure 3.

30-year old woman with endometrioid adenocarcinoma within a pre-existing ovarian endometrioma. Transverse multiplanar reformatted contrast-enhanced MDCT image shows a large, sharply demarcated left pelvic mass. The dimensions of the tumor were 15.8 × 8 × 15.4 cm. Hyperdense components (arrows) were measured with the same values, as on pre-contrast images, therefore the mass was considered as non-enhancing. Based on MDCT findings, the diagnosis of a benign hemorrhagic adnexal mass lesion was made. (Parameters: 16-row CT scanner; mAs: 110; kV: 120; detector collimation: 16 × 0.75 mm; slice thickness: 0.8 mm; reconstruction interval: 0.5 mm; pitch: 1.2; contrast material: 120 ml; flow rate: 3 ml/sec; scan delay: 70 sec).

Figure 4.

30-year old woman with endometrioid adenocarcinoma within an ovarian endometrioma. Coronal multiplanar reformatted contrast-enhanced MDCT image depicts a large, heterogeneous mass lesion, mainly hyperdense, closely related to the uterine body (long arrow). (Parameters: 16-row CT scanner; mAs: 110; kV: 120; detector collimation: 16 × 0.75 mm; slice thickness: 0.8 mm; reconstruction interval: 0.5 mm; pitch: 1.2; contrast material: 120 ml; flow rate: 3 ml/sec; scan delay: 70 sec).

MR imaging examination of the pelvis on a 1.5-Tesla MR unit (Intera, Philips), using a pelvic-phased array coil was followed. The protocol included turbo spin echo T2-weighted images in transverse, sagittal and coronal planes and axial spin echo T1-weighted images, before and after the application of a fat saturation prepulse. Dynamic contrast-enhanced fat-suppressed gradient-echo T1-weighted imaging was performed in the sagittal plane, after a rapid hand injection of gadolinium chelate components (Omniscan, GE Healthcare). Axial diffusion-weighted (DW) images, with a b-factor of 0 and 800 seconds/mm2 were also performed. The tumor had parts of high signal intensity on both T1 and T2-weighted images, suggestive for the presence of subacute haemorrhage. Others parts slightly hyperintense and extremely hypointense on T1 and T2-weighted images, respectively were considered as indicative for acute haemorrhage (Figure 5, 6, 7). The presence of a soft-tissue component, detected with intermediate signal intensity, similar to that of the normal myometrium on both T1 and T2-weighted images and early, strong enhancement on dynamic post-contrast MR images was revealed (Figure 5, 6, 7, 8). Subacute hemorrhagic components had intermediate signal intensity on diffusion-weighted images and a mean apparent diffusion coefficient value (ADC) of 1.37 × 10−3 mm2/second (Figure 9, 10). Acute hemorrhagic parts cause a dramatic signal drop in the area, due to T2* effect and had no measurable ADC values. The soft-tissue component was detected hyperintense on DW images, with low ADC values (1.05 × 10−3 mm2/second, Figure 9, 10), due to restricted diffusion. Ovarian malignancy was strongly indicated based on both conventional and diffusion-weighted MR imaging findings. The presence of an enhancing component within a blood-filled ovarian cyst was considered as suggestive of malignant transformation of a pre-existing endometrioma.

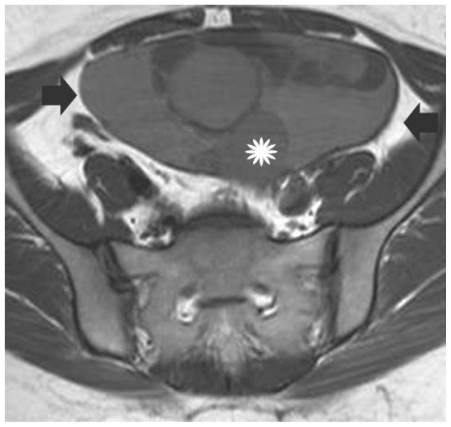

Figure 5.

30-year old woman with left endometrioid adenocarcinoma developed in a pre-existing ovarian endometrioma. Transverse T1-weighted image depicts a sharply-delineated left pelvic mass. The lesion was heterogeneous, mainly with parts (arrows) of signal intensity slightly higher than that of muscle or normal myometrium, a finding suggestive for the presence of hemorrhagic content. A soft tissue component (asterisk) with intermediate signal intensity is also revealed. (Parameters: 1.5 Tesla magnet; TR: 400 msec; TE: 14 msec; slice thickness: 5 mm; gap: 0.5 mm).

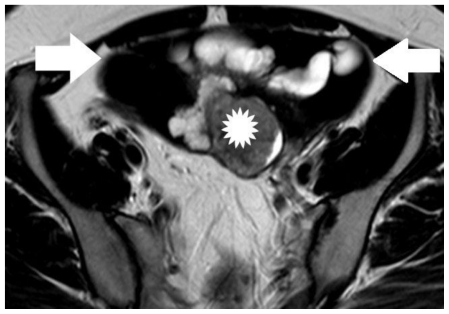

Figure 6.

30-year old woman with endometrioid adenocarcinoma within an ovarian endometrioma. Transverse T2-weighted image shows a multicystic left adnexal mass lesion. Hyperintense parts on T1-weighted images were detected with very low signal intensity on T2-weighted images (arrows), a finding suggestive mainly of acute haemorrhage (these elements corresponded to hyperdense parts on CT examination). The soft tissue component (asterisk) was detected with intermediate signal intensity. (Parameters: 1.5 Tesla magnet; TR: 4000 msec; TE: 120 msec; slice thickness: 5 mm; gap: 0.5 mm).

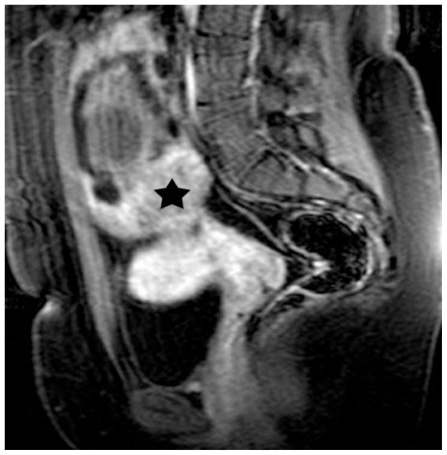

Figure 7.

30-year old woman with endometrioid adenocarcinoma within an ovarian endometrioma. Sagittal T2-weighted image shows lesion signal herogeneity. The mass was seen close to the uterus body (arrow). The signal intensity of the soft-tissue component (asterisk) was similar to that of normal myometrium (arrow). (Parameters: 1.5 Tesla magnet; TR: 4000 msec; TE: 120 msec; slice thickness: 5 mm; gap: 0.5 mm).

Figure 8.

30-year old woman with endometrioid adenocarcinoma developed in a pre-existing ovarian endometrioma. Sagittal fat-saturated dynamic post-contrast T1-weighted image demonstrates soft tissue element (asterisk), with early and strong enhancement, a finding strongly indicative of malignancy (Parameters: 1.5 Tesla magnet; TR: 11 msec; TE: 5.5msec; flip angle; 20°, slice thickness: 3.5mm; contrast material: 2 ml/kg; early phase: 70 sec).

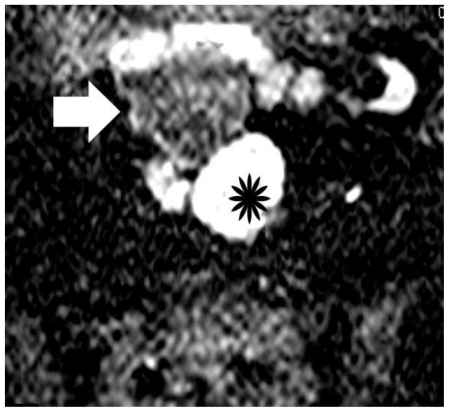

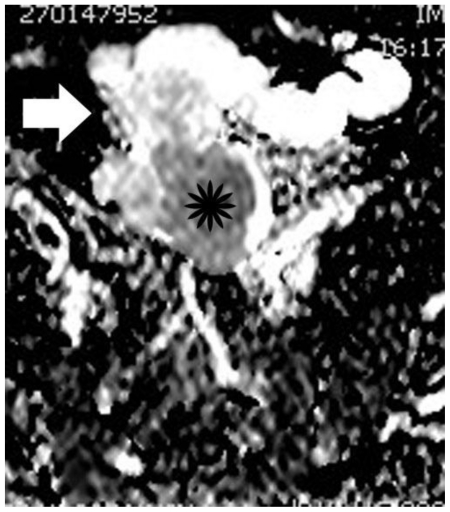

Figure 9.

30-year old woman with endometrioid adenocarcinoma in a pre-existing ovarian endometrioma. Transverse diffusion-weighted echo planar image shows hyperintensity of the soft-tissue component (asterisk) due to restricted diffusion, a finding highly suggestive of malignancy. Areas of subacute hemorrhage (arrow) are detected with intermediate signal intensity. (Parameters: 1.5 Tesla magnet; TR: 3800 msec; TE: 120 msec; slice thickness: 5 mm; gap: 0.5 mm, b-value: 800 seconds/mm2).

Figure 10.

30-year old woman with endometrioid adenocarcinoma developed in a pre-existing ovarian endometrioma. Apparent diffusion coefficient map of image illustrated in Figure 9. The soft tissue component (asterisk) is hypointense, with an ADC value of 1.05 × 10−3 mm2/s, a finding suggestive of restricted diffusion. Subacute hemorrhagic component (arrow) is detected with intermediate signal intensity and an ADC value of 1.37 × 10−3 mm2/s. The normal ADC values of myometrium and endometrium in this case were 1.79 × 10−3 mm2/sec; and 1.43 × 10−3 mm2/sec, respectively.

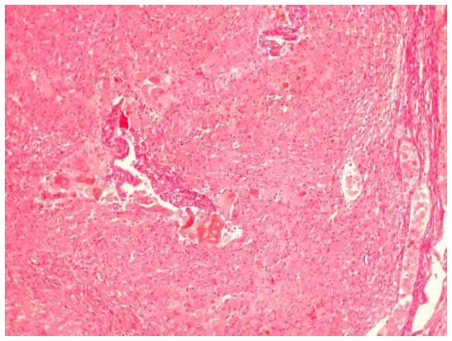

Fertility-preserving surgery was discussed with the patient and in this context initial laparotomy consisted of left salpingo-oophorectomy, biopsies of the right ovary, omenectomy, and peritoneal washings. Pathology showed a well-differentiated ovarian endometrioid adenocarcinoma arising from endometriosis (Figure 11, 12). Microscopic neoplastic foci of the same histologic type, and endometriotic implants were found on the contralateral ovary (Figure 13). Following this report the patient was counselled that fertility preservation was not possible given the presence of malignancy on the right ovary too. A second procedure was followed consisting of total abdominal hysterectomy and right salpingo-oophorectomy. The pathologic stage was IB by FIGO classification. The patient is now well, without signs of recurrence, 18 months after surgery on follow-up MR examination.

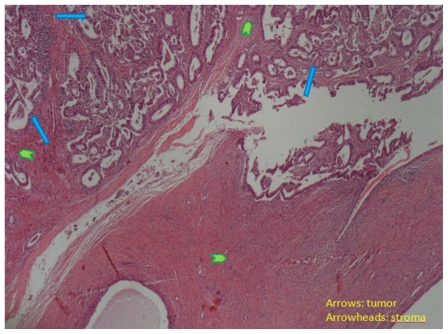

Figure 11.

30-year old woman with endometrioid adenocarcinoma within an ovarian endometrioma. Well differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma (arrows) of the ovary invading the ovarian stroma (arrowheads, H-E X40).

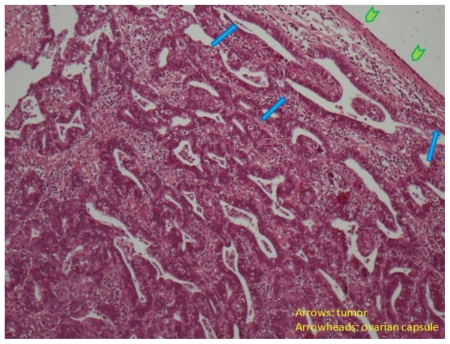

Figure 12.

30-year old woman with endometrioid adenocarcinoma within an ovarian endometrioma. Well differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma (arrows) of the ovary beneath the ovarian capsule (arrowheads, H-E X100).

Figure 13.

30-year old woman with endometriosis and endometrioid ovarian adenocarcinoma. Microscopic appearance of an endometriotic focus of the right ovary (H-E X100).

DISCUSSION

Endometriosis is a common disease affecting primarily women in the reproductive age group (1, 2, 3, 4, 5). Malignant transformation is a rare complication of endometriosis, with an incidence of malignancy in patients with ovarian endometriotic cysts reported 0.6–0.8% (6). Approximately 75% of tumors in patients with endometriosis arise in endometriotic cysts and less often in the rectovaginal septum, rectum and sigmoid colon (1). Endometrioid carcinoma of the ovary is the commonest histologic type of malignancy occurring in endometriomas, as it was in our case, followed by clear cell adenocarcinoma (1, 2, 6, 7, 8). Ovarian carcinomas associated with endometriosis are more often seen in younger women (30–50 years of age) when compared to ovarian carcinoma in women without endometriosis, as it was in this patient.

The typical appearance of an endometriosis-related carcinoma is that of a large ovarian cyst with hemorrhagic fluid and soft-tissue components, enhancing on postcontrast T1-weighted images (6, 7, 8). The above findings were seen in this patient. Both MDCT and MR imaging detected a large, multicystic adnexal mass, mainly composed of hemorrhagic content. The detection of the enhancing soft-tissue element was difficult on CT, due to the lesion hyperdensity. MR imaging, on the other hand clearly identified the solid tissue component, detected with intermediate signal intensity on T2-weighted images and enhancing strongly during the early phase, on dynamic contrast-enhanced images. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging has proved useful in differentiating malignancies from benign tumors due to the differences in contrast tissue behavior caused by neoangiogenesis (9, 10, 11). Ovarian tumors usually demonstrate an early and strong enhancement, as was the case in our patient. Based on MR imaging features, a reliable preoperative characterization of the malignant nature of the mass was possible.

Diffusion-weighted (DW) MR imaging has recently been used in the evaluation of the female pelvic malignancies (12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18). It has been reported that high b value DW imaging depicted high signal intensity for malignant tumors when compared to normal tissues and benign lesions with lower ADC values for the former, because malignancies have a larger cell diameter and denser cellularity, therefore restricting water diffusion. These criteria were also met in our patient, although the MR diagnosis was readily made by the conventional MR imaging. The tumorous component was hyperintense on DW images, with a low ADC value (1.05 × 10−3 mm2/second), a finding suggestive of restricted diffusion. Hemorrhagic components on the other hand had intermediate signal intensity on DW imaging, with ADC values of 1.37 × 10−3 mm2/second. Endometriomas are reported with low ADC values, when compared with benign and malignant cystic ovarian malignancies, due to the presence of thick proteinaceous fluid or blood products (16, 17, 18).

Differential diagnosis of an endometriosis-related carcinoma should include intracystic blood clot and decidual changes of the ectopic endometrium within an endometrioma during pregnancy (6, 7, 19). The absence of contrast enhancement enables the reliable recognition of a blood clot within an adnexal cystic lesion (6). Ectopic endometrial stroma can undergo decidual change during pregnancy and close follow-up of pregnant women with such changes in an endometrioma is mandatory to rule out malignancy (6, 19).

TEACHING POINT

Endometriosis is considered a precancerous condition for ovarian malignancy, although rarely. The presence of an enhancing soft-tissue component within a blood-filled ovarian cystic mass is suggestive of malignancy and ovarian carcinoma arising in an endometriotic cyst should be considered. Early and strong enhancement of the soft-tissue element on dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging and restricted diffusion on DW MR images confirm the diagnosis of malignancy.

Table 1.

Summary table for endometrioid adenocarcinoma developed within a pre-existing ovarian endometrioma.

| Etiology | Unopposed estrogen therapy |

| Incidence | 0.6–0.8% |

| Age predilection | 4–5th decade |

| Treatment | Staging laparotomy including radical hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy |

| Prognosis | Depends mainly on the stage of the disease at the time of diagnosis |

| Imaging findings | MDCT-plain images: hyperdense parts (hemorrhagic content) MDCT-contrast-enhanced images: hyperdense, non-enhancing parts (hemorrhagic content): difficult to appreciate the contrast-enhancing elements MRI-T1: hyperintense (hemorrhagic content) and isointense parts (tumorous component), when compared to normal myometrium MRI-T2: hyperintense and extremely hypointense components (acute and subacute hemorrhagic content, respectively) and isointense parts (tumorous component), when compared to normal myometrium MRI-DW: isointense and slightly hyperintense components (hemorrhagic content) and hyperintense parts (tumorous component) MRI-contrast-enhanced images: strong and early enhancement on dynamic MRI (tumorous component) |

Table 2.

Differential table for endometrioid adenocarcinoma developed within a pre-existing ovarian endometrioma.

| US | CT | MRI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carcinoma developed in a pre- existing ovarian endometrioma | Complex adnexal mass, with cystic and solid elements. Color and pulsed Doppler may show presence of blood vessels within solid components; a low resistive index and pulsatility index may also be detected | Multicystic adnexal mass, mainly with hyperdense parts, due to hemorrhagic content. The detection of solid, contrast-enhancing elements may be difficult | Hemorrhagic component T1: hyperintense T2: hyperintense or hypointense DWI: may show restricted diffusion Pattern of contrast enhancement: none or wall and septa enhancement (smooth, usually of thickeness < 3mm) Neoplastic component T1: intermediate T2: intermediate DWI: restricted diffusion Pattern of contrast enhancement: strong, early, heterogeneous enhancement |

| Intracystic blood clot | Complex adnexal mass, with cystic elements and solid echogenic parts. Color Doppler may show absence of blood vessels within solid elements | Multicystic adnexal mass, predominantly hyperdense | T1: hyperintense T2: hyperintense or hypointense DWI: may show restricted diffusion Pattern of contrast enhancement: none or wall and septa enhancement (smooth, usually of thickeness < 3mm) |

| Decidual changes developed within endometrioma during pregnancy | Complex adnexal mass, with cystic-solid parts or nodular projections. Color Doppler may show presence of vascularity within solid elements or nodular projections | Hemorrhagic component T1: hyperintense T2: hyperintense or hypointense DWI: may show restricted diffusion Pattern of contrast enhancement: no gadolinium is administered Solid component T1: intermediate T2: intermediate Serial monitoring is mandatory |

ABBREVIATIONS

- MDCT

multidetector CT

- MR

magnetic resonance

- DW

diffusion-weighted

- ADC

apparent diffusion coefficient

- FIGO

International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics

- i.v.

intravenous.

REFERENCES

- 1.Woodward PJ, Sohaey R, Mezzetti TP., Jr Endometriosis: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2001;21(1):193–216. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.21.1.g01ja14193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gougoutas CA, Siegelman ES, Hunt J, Outwater EK. Pelvic endometriosis: various manifestations and MR imaging findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175(2):353–358. doi: 10.2214/ajr.175.2.1750353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spencer JA, Weston MJ. Imaging in endometriosis. Imaging. 2003;15:63–71. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Umaria N, Olliff JF. Imaging features of pelvic endometriosis. Br J Radiol. 2001;74(882):556–562. doi: 10.1259/bjr.74.882.740556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kinkel K, Frei KA, Balleyguier C, Chapron C. Diagnosis of endometriosis with imaging: a review. Eur Radiol. 2006;16(2):285–298. doi: 10.1007/s00330-005-2882-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takeuchi M, Matsuzaki K, Uehara H, Nishitani H. Malignant transformation of pelvic endometriosis: MR imaging findings and pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2006;26:407–417. doi: 10.1148/rg.262055041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanaka YO, Yoshizako T, Nishida M, Yamaguchi M, Sugimura K, Itai Y. Ovarian carcinoma in patients with endometriosis: MR imaging findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175(5):1423–1430. doi: 10.2214/ajr.175.5.1751423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu TT, Coakley FV, Qayyum A, Yeh BM, Joe BN, Chen LM. Magnetic resonance imaging of ovarian cancer arising in endometriomas. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2004;28(6):836–838. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200411000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomassin-Naggara I, Bazot M, Darai E, Callard P, Thomassin J, Cuenod CA. Epithelial ovarian tumors: value of dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging and correlation with tumor angiogenesis. Radiology. 2008;248(1):148–159. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2481071120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bazot M, Darai E, Nassar-Slaba J, Lafont C, Thomassin- Nagara I. Value of magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of ovarian tumors: a review. J Comput Assist Tomog. 2008;32(5):712–723. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e31815881ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sohaib SAA, Sahdev A, Trappen PV, Jacobs IJ, Reznek RH. Characterization of adnexal mass lesions on MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:1297–1304. doi: 10.2214/ajr.180.5.1801297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inada Y, Matsuki M, Nakai G, et al. Body diffusion- weighted MR imaging of uterine endometrial cancer: is it helpful in the detection of cancer in nonenhanced MR imaging? Eur J Radiol. 2009;70(1):122–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2007.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujii S, Matsusue E, Kigawa J, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the apparent diffusion coefficient in differentiating benign from malignant uterine endometrial cavity lesions: initial results. Eur Radiol. 2008;18(2):384–389. doi: 10.1007/s00330-007-0769-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tamai K, Koyama T, Saga T, et al. The utility of diffusion-weighted MR imaging for differentiating uterine sarcomas from benign leiomyomas. Eur Radiol. 2008;18(4):723–730. doi: 10.1007/s00330-007-0787-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naganawa S, Sato C, Kumada H, Ishigaki T, Miura S, Takizawa O. Apparent diffusion coefficient in cervical cancer of the uterus: comparison with the normal uterine cervix. Eur Radiol. 2005;15(1):71–78. doi: 10.1007/s00330-004-2529-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakayama T, Yoshimitsu K, Irie H, et al. Diffusion-weighted echo-planar MR imaging and ADC mapping in the differential diagnosis of ovarian cystic masses: usefulness of detecting keratinoid substances in mature cystic teratomas. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2005;22:271–278. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katayama M, Masui T, Kobayashi S, et al. Diffusion-weighted echo planar imaging of ovarian tumors: is it useful to measure apparent diffusion coefficients? J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2002;26(2):250–256. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200203000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moteki T, Ishizaka H. Diffusion-weighted EPI of cystic ovarian lesions: evaluation of cystic contents using apparent diffusion coefficients. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2000;12(6):1014–1019. doi: 10.1002/1522-2586(200012)12:6<1014::aid-jmri29>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miyakoshi K, Tanaka M, Gabionza D, et al. Decidualized ovarian endometriosis mimicking malignancy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171(6):1625–1626. doi: 10.2214/ajr.171.6.9843300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]