Abstract

We present a case of an incidentally discovered holohemispheric developmental venous anomaly (DVA) in a 12 year old, conclusively characterized by 3D T2* multi-echo sequence susceptibility weighted angiographic imaging (SWAN). For the evaluation of head trauma, abnormal right intraparenchymal and periventricular vascularity was identified by a non contrast head CT scan. Conventional MRI sequences revealed prominent veins with findings suspicious of a DVA. A definitive diagnosis was made by identifying angiographic features typical for DVA by augmented susceptibility weighted angiographic imaging. Using this sequence the entire hemispheric extent of the anomaly without complicating features was definitively characterized, negating the need for a catheter based angiographic study. A holohemispheric DVA in a child to our knowledge has not been previously described.

Keywords: Developmental Venous Anomaly, DVA, Susceptibility weighted imaging, MRI

CASE REPORT

A 12 year old boy was kicked in the head at school and presented with a two day history of headache. His neurological examination was unremarkable. A non-enhanced CT (NECT) of the head showed an abnormal periventricular vascular lesion on the right cerebral hemisphere (Fig. 1). Conventional multi sequence gadolinium enhanced MRI of the brain study poorly identified a DVA (Fig. 2, 3, 4 and 5). Conventional time of flight MR angiography (MRA) and time resolved imaging of contrast kinetic (TRICKS) confirmed a vascular anomaly without differentiating an arteriovenous malformation (AVM) from a DVA (Fig. 6). A T2* weighted multi echo 3D volumetric susceptibility angiographic sequence (SWAN, Optima 450w, General Electric, Milwaukee, WI, USA) revealed the pathognomonic caput medusae venous structure and recipient veins of a DVA involving the entire right cerebral hemisphere (Fig. 4), definitively excluding other vascular malformations.

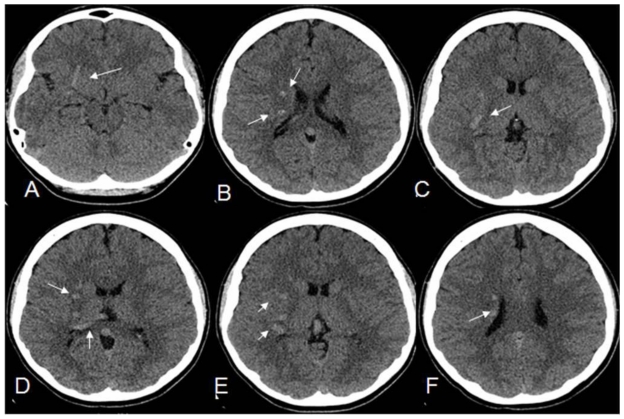

Figure 1.

12 year old male with right holohemispheric Developmental Venous anomaly (DVA). Select axial non-enhanced CT of the head. (Protocol: kV 120, mA 250, 2.5mm slice thickness). Multiple serpiginous hyperattenutating vascular structures within the right cerebral hemisphere and marginating the right occipital horn (small white arrows).

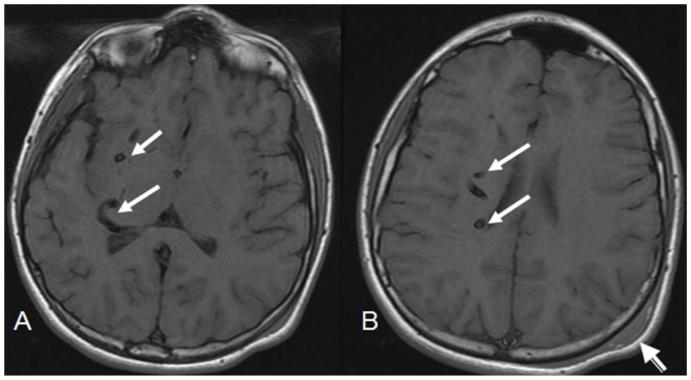

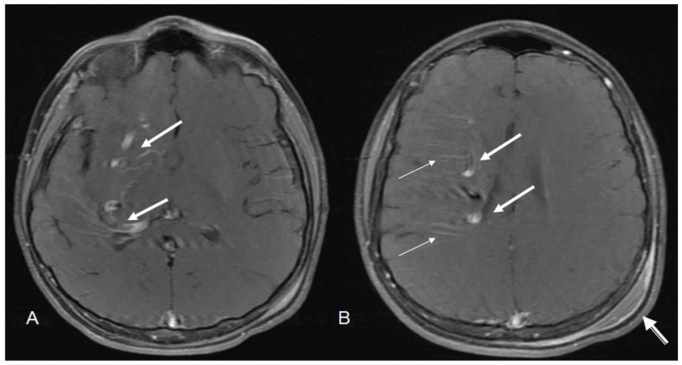

Figure 2.

12 year old male with right holohemispheric developmental venous anomaly (DVA). Select axial T1 MRI brain images. (Protocol: Pulse sequence; 2D Spin Echo, TR: 516.7, TE: 13, slice thickness: 5mm, Nex 1.0). Vascular flow voids within the right cerebral hemisphere and marginating the right lateral ventricle (white arrows). Note no caput medusae. Post traumatic left parietal scalp hematoma (arrow head).

Figure 3.

12 year old male with right holohemispheric developmental venous anomaly (DVA). Select axial MRI T2 brain images. (Protocol: Pulse sequence; 2D Spin Echo, TR: 4053.9, TE: 81.5, slice thickness: 5mm, Nex 1.0). Vascular flow voids within the right cerebral hemisphere and marginating the right lateral ventricle (white arrows). Note no caput medusae. Post traumatic left parietal scalp hematoma (arrow head).

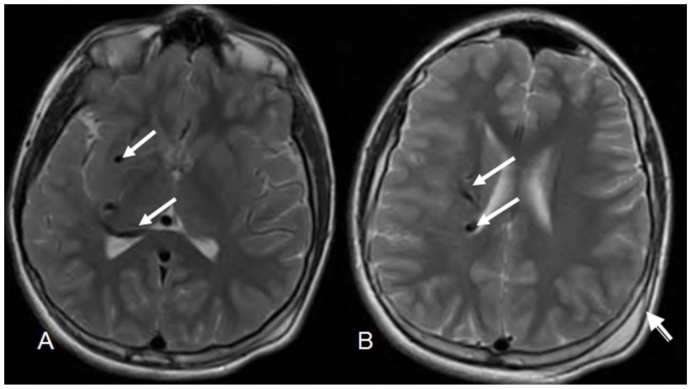

Figure 4.

12 year old male with right holohemispheric developmental venous anomaly (DVA). Select axial FLAIR MRI brain images. (Protocol: Pulse sequence; 2D FLAIR, TR: 516.7, TE 13, slice thickness 5mm, Nex 1.0). Vascular flow voids within the right cerebral hemisphere and marginating the right lateral ventricle (white arrows). Note no caput medusae. Post traumatic left parietal scalp hematoma (arrow head).

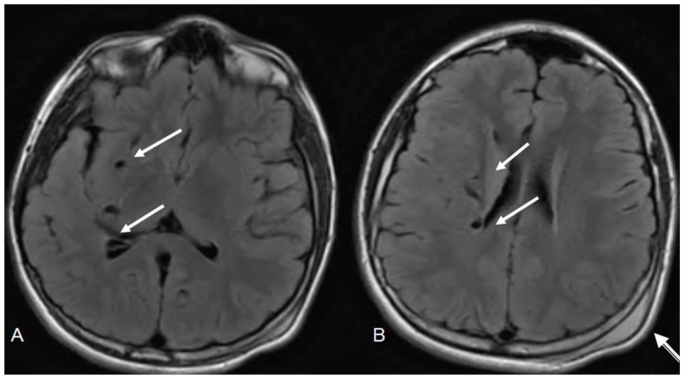

Figure 5.

12 year old male with right holohemispheric developmental venous anomaly (DVA). Select axial T1 post contrast MRI brain images. (Protocol: Pulse Sequence; 2 D Spin Echo, TR 846, TE 11.4, slice thickness 5mm, Nex 1.0, Multihance (Bracco Diagnostics, Princeton,NJ), 13ml injected through right forearm). Enhancement of the draining vein (large arrows) with poor visualization of radicular veins of the caput medusae (small arrows). Post traumatic scalp hematoma (arrow head).

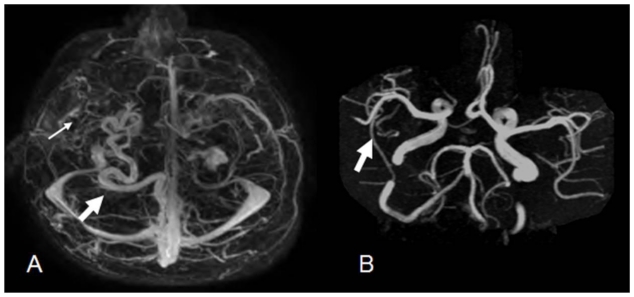

Figure 6.

12 year old male with right holohemispheric developmental venous anomaly (DVA). Select axial TRICKS (Time resolved imaging of contrast kinetics, Optima 450, General Electric, Milwaukee, WI, USA) contrast enhanced MR angiography image of the brain. (Protocol: Pulse Sequence; 3D Gradient Recall Echo, TR: 3.6, TE: 1.4, Slice Thickness 2.4mm Nex: 0.5). Tortuous draining vein terminating in straight sinus (white arrow). Cluster of vascularity (small arrow) not typical in appearance for a caput medusae. B. Select axial Time of Flight (TOF) MRA image of the brain. (Protocol: Pulse sequence; 3D Gradient Recall Echo, Maximum intensity projection TR: 25, TE: 3.4, Slice Thickness 1.4mm, Nex 1.0), No prominent right hemispheric arterial feeder vessel or vascular nidus (arrow).

DISCUSSION

Developmental venous anomalies (DVAs) are low flow congenital brain vascular malformations that as the name describes are solely of venous origin. The anomaly drains normal brain tissue and has a distinctive imaging appearance, characterized by a linear branched configuration of veins, referred to as caput medusae. These veins converge into a dominant recipient vein that drains either into a dural sinus or ependymal veins with a varied transhemispheric brain parenchymal course [1]. They are the most common vascular brain malformation with an incidence of 2.6% of 4069 autopsies performed and occur most commonly in the frontal lobes [2, 3]. Holohemispheric DVAs are uncommon and to our knowledge only one other case report of such an anomaly, diagnosed by catheter angiography in an adult has been reported [4].

Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) is the criterion standard for characterizing the micro and macro vascular structure as well as the hemodynamics of a DVA [2]. DVAs are visualized by CT and conventional MRI sequences. These non invasive methods are however limited in their ability to comprehensively determine the true extent and definitive angioarchitecture of the lesion for an accurate diagnosis. Conventional T2 spine echo sequences are sensitive to high flow vessels but are poor at defining low flow lesions. Gadolinium enhanced sequences opacify portions of the larger vessel components of a DVA and is acquired in relative thick sections. This limits a definitive diagnosis and may also miss small DVAs.

In the literature and by MRI machine manufacturers, the term susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI) has been used to describe varied phenomenon. Some authors have used this term to describe any sequences that allow for the detection of tissue related T2* signal susceptibility effect, such as conventional 2D T2* gradient recall echo (GRE) sequences. Susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI) has also been designated as a method by which the tissue related T2* susceptibility effect is enhanced by 3D velocity compensated gradient recalled echo sequences, using concomitantly acquired phase imaging information [5]. Although conventional 2D T2* GRE sequences are sensitive for identifying small venous vessels with low flow, they are limited by slice thickness, poor signal to noise ration and an increased acquisition time that may be up to 8 minutes [2,5]. SWI minimal intensity projection images provide high resolution images sensitive to T2* effect, inclusive of low venous flow as seen in DVA’s.

T2* weighted susceptibility angiography ( SWAN, Optima 450, General Electric, Milwaukee, WI, USA) is a unique 3D-gradient echo T2*-based multi-echo sequence with varied TE times within one TR time period that allows for imaging of tissues with varying degrees of T2* contrast and is technically distinct from conventional 2D T2*GRE and SWI. A combined weighted average of all the echoes is collated by a specialized post-processing algorithm to obtain whole brain sub-millimeter-resolution 3D images [6]. The varied TE times reduces chemical shift artifact that contributes to image blurring on conventional 2D T2* GRE sequences. This also increases susceptibility signal and doubles the signal-to-noise ratio as compared to conventional 2D T2* GRE sequences. With this method large and particularly small venous structures containing deoxygenated hemoglobin as in a DVA are better characterized with greater spatial resolution for a more accurate imaging diagnosis. Although SWAN and SWI imaging are acquired differently and are vendor specific, their indications and image quality are similar.

The majority of DVAs found incidentally have a benign course [7]. The retrospective risk for hemorrhage is 0.22% per year and the prospective risk 0.68 % per year [1, 2]. They are symptomatic when spontaneous thrombosis of the draining vein with subsequent venous infarction or hemorrhage occurs. A review of symptomatic thrombosed DVA’s by Ruiz et al identified venous infarction in 53%, parenchymal hemorrhage in 37%, subarachnoid hemorrhage in 5% and no lesions in 5% of 21 patients [1]. DVA’s may be additionally symptomatic if associated with other vascular malformation, most commonly cavernous malformations (CMs), which are found in 13 to 40% of the cases [2]. Parenchymal bleeds from these malformations are considered to account for the majority of symptomatic DVAs.

Varied arterialization associated with DVAs is referred to as atypical types and occur very rarely [1, 2]. In particular, SWI may also be helpful in identifying high flow within arterialized vessels and has been quoted as being 100% sensitive and 96% specific for arteriovenous shunts [9]. This has not been documented for SWAN imaging in the literature. Arteriovenous shunting may also be identified by time resolved imaging of contrast kinetics (TRICKS) and is a key factor in differentiating DVA’s from AVM’s. MRI sequences that allow for detection of paramagnetic substances allows for identification of CMs associated with DVAs [8]. The presence of clinical symptoms, CM, hemorrhage, and arterialization with and without an AVM nidus requires further diagnostic imaging with DSA [1]. Improved characterization of DVAs by SWAN and SWI imaging could allow for differentiation between typical and types associated with CMs and arterialization.

The current understanding of DVAs is based primarily on adult studies. There are no published studies for the evaluation DVAs in the pediatric population [2]. The type and frequency of associated features in the pediatric population may be different [2]. Vigilance for accurate diagnosis of DVAs using advanced MRI techniques and to additionally evaluate for associated features are important considerations for both the radiologist and clinician in the work up and management of such conditions in the pediatric population.

TEACHING POINT

Holohemispheric DVAs in the pediatric population are rarely diagnosed, although the entity is the most common brain vascular anomaly. Susceptibility weighted angiography (SWAN) is a unique T2 star weighted sequence that definitively characterizes the angioarchitecture and associated features of a DVA for an accurate imaging diagnosis. Acquiring this or similar type of sequences such as SWI may negate the need for catheter based angiography if no atypical features of a DVA are identified.

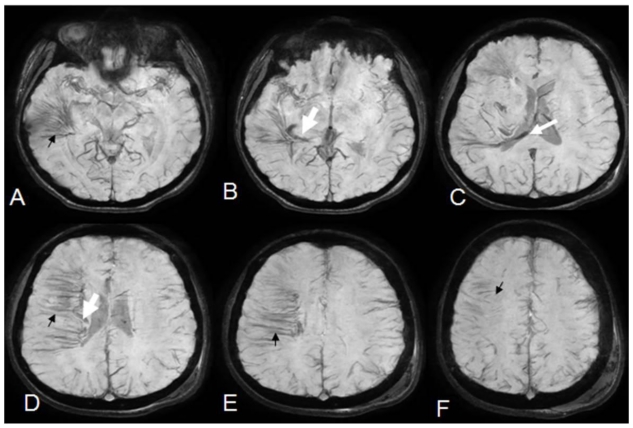

Figure 7.

12 year old male with right holohemispheric developmental venous anomaly (DVA). Serial minimum projection intensity sequential axial susceptibility weighted angiography (SWAN) images of the brain. (Protocol: Pulse sequence; 3D Gradient Recall Echo, TR: 76.6, TE: 48.1, slice thickness 8mm Nex: 0.70). Distinct characterization of the diminutive veins comprising multiple venous radicals constituting the medusa head within all the right hemispheric lobes (small black arrows). Singular recipient vein coursing along the right lateral ventricle with entry to the straight sinus through the occipital horn (white arrows).

Table 1.

Summary table for developmental venous anomaly (DVA)

| Etiology | Uncertain, possibly arrested intrauterine loss of venous structures with compensatory recruitment of local veins |

| Gender Ratio | Slight male dominance |

| Treatment | None unless symptomatic or with atypical types or association with other vascular lesions |

| Age | Adult and pediatric |

| Associated Entities |

|

| Prognosis |

|

Table 2.

Imaging Findings of developmental venous anomalies (DVA)

| CT without and or with iodinated contrast | MRI T1 and T2 | Gadolinium enhanced MRI | Hemosiderin and deoxyhemoglobin sensitive MRI sequence (SWI and SWAN) | Catheter Angiography |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 3.

Differential diagnosis table for developmental venous anomaly (DVA)

| Developmental Venous anomaly | Dural sinus thrombosis with collateral venous drainage | Sturge-Weber Syndrome | Arteriovenous Malformation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT without or with iodinated contrast |

|

|

|

|

| MRI T1 |

|

|

|

|

| MRI T2 |

|

|

|

|

| Gadolinium enhanced MRI |

|

|

|

|

| MRI diffusion |

|

|

|

|

| Catheter Angiography |

|

|

|

|

ABBREVIATIONS

- AVM

Ateriovenous malformation

- CM

Cavernous malformation

- CT

Computed tomography

- DSA

Digital subtraction angiography

- DVA

Developmental venous anomaly

- FLAIR

Fluid attenuated inversion recovery

- GRE

Gradient recall echo

- MR

Magnetic resonance

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NECT

Non-enhanced computed tomography

- SWAN

Susceptibility weighted angiography

- SWI

Susceptibility weighted imaging

- TE

Echo time

- TOF

Time of flight

- TR

Repetition time

- TRICKS

Time resolved imaging of contrast kinetics

- T2*

Susceptibility Weighted

REFERENCES

- 1.San Millán Ruíz D, Yilmaz H, Gailloud P. Cerebral Developmental Venous Anomalies: Current Concepts. Ann Neurol. 2009;66(3):271–283. doi: 10.1002/ana.21754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.San Millán Ruíz D, Gailloud P. Cerebral developmental venous anomalies. Childs Nerv Syst. 2010 Oct;26(10):1395–406. doi: 10.1007/s00381-010-1253-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarwar M, McCormick WF. Intracerebral venous angioma. Case Report and review. Arch Neurol. 1978;35(5):323–325. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1978.00500290069012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aagaard BD, Song JK, Eskridge JM, Mayberg MR. Complex right hemisphere developmental venous anomaly associated with multiple facial hemangiomas. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1999 Apr;90(4):766–9. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.90.4.0766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sehgal V, Delproposto Z, Haacke EM, et al. Clinical applications of neuroimaging with susceptibility-imaging. J Magn Reso Imaging. 2005 Oct;22(4):439–450. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lummel N, Boeckh-Behrens T, Schoepf V, Burke M, Brückmann H, Linn J. Presence of a central vein within white matter lesions on susceptibility weighted imaging: a specific finding for multiple sclerosis. Neuroradiology. 2011 May;53(5):311–7. doi: 10.1007/s00234-010-0736-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McLaughlin MR, Kondziolka D, Flickinger JC, Lunsford S, Lunsford LD. The prospective natural history of cerebral venous malformations. Neurosurgery. 1998 Aug;43(2):195–200. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199808000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Champfleur NM, Langlois C, Ankenbrandt W, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of cerebral cavernous malformations with susceptibility-weighted imaging. Neurosurgery. 2011 Mar;68(3):641–7. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e31820773cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jagadeesan BD, Delgado Almandoz JE, Moran CJ, Benzinger TL. Accuracy of susceptibility-weighted imaging for the detection of arteriovenous shunting in vascular malformations of the brain. Stroke. 2011 Jan;42(1):87–92. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.584862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee C, Pennington MA, Kenney CM., 3rd MR evaluation of developmental venous anomalies: medullary venous anatomy of venous angiomas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1996 Jan;17(1):61–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]