Abstract

Symptomatic differences and the impact of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) have not been clarified in patients with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The purpose of this study is to assess the differences of GERD symptoms among asthma, COPD, and disease control patients, and determine the impact of GERD symptoms on exacerbation of asthma or COPD by using a new questionnaire for GERD. A total of 120 subjects underwent assessment with the frequency scale for the symptoms of GERD (FSSG) questionnaire, including 40 age-matched patients in each of the asthma, COPD, and disease control groups. Asthma and control patients had more regurgitation-related symptoms than COPD patients (p<0.05), while COPD patients had more dysmotility-related symptoms than asthma patients (p<0.01) or disease control patients (p<0.01). The most distinctive symptom of asthma patients with GERD was an unusual sensation in the throat, while bloated stomach was the chief symptom of COPD patients with GERD, and these symptoms were associated with disease exacerbations. The presence of GERD diagnosed by the total score of FSSG influences the exacerbation of COPD. GERD symptoms differed between asthma and COPD patients, and the presence of GERD diagnosed by the FSSG influences the exacerbation of COPD.

Keywords: GERD, asthma, COPD, FSSG, dismotility

Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is a potential trigger for supra-esophageal manifestations of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).(1,2) The prevalance of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) in asthma patients was 42% to 69% according to the questionnaire for the diagnosis of reflux disease (QUEST).(3,4) In COPD patients, the prevalance was 37% according to the Mayo clinic GERD questionnaire.(5,6) GER is common in patients with pulmonary disease and is involved in the pathophysiology of exacerbation of asthma and COPD, but proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) show limited efficacy for improvement of pulmonary function and respiratory symptoms in asthma or COPD patients with GERD.(7–9) Failure of PPI therapy is observed in patients who are diagnosed as having GERD by endoscopy, pH testing and esophageal impedance.(10) Therefore, another mechanism that has attracted attention is gastric motor activity.(11) In contrast, QUEST covers more typical symptoms of acid regurgitation, the frequency scale for the symptoms of GERD (FSSG) is a recently developed questionnaire that covers 12 symptoms, including not only typical regurgitation symptoms such as ”heartburn” but also dysmotility symptoms such as ”heavy stomach”.(12) GERD also changes with age,(13) and there have been no reports about the prevalance and features of GERD symptoms in age-matched asthma and COPD patients with GERD diagnosed by the FSSG.

The aims of this study were to compare the prevalence of GERD and the symptoms of GERD among asthma, COPD, and disease control patients. The impact of GERD (evaluated by the FSSG) on exacerbation of asthma and COPD was also examined.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

A total of 120 subjects underwent the FSSG, including 40 patients with asthma, 40 patients with COPD, and 40 disease control subjects without asthma or COPD. The characteristics of the subjects enrolled in this study are shown in Table 1. The diagnosis of asthma was established according to the Global Initiative for Asthma report (GINA),(14) as described previously,(4) while a diagnosis of COPD was established according to the Global Initiative for Chronic obstructive Lung disease report (GOLD).(15) The disease control patients had hypertension (n = 26), hyperlipidemia (n = 11), insomnia (n = 1), prostatomegaly (n = 1), and cervical spondylosis (n = 1) without respiratory symptoms and without receiving respiratory medications. Patients were excluded if they had a history of esophageal, gastric, or duodenal surgery, were using acid-suppressing drugs of PPI, H2 receptor antagonist or gastroprokinetic agents such as selective serotonin (5HT4) agonists, were mentally incompetent, or were being treated with an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor. Since COPD occurs rather older than young, less than 50 years old were excluded.

Table 1.

Characteristics of asthma, COPD, and disease control

| Asthma | COPD | Disease control | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, year | 65.5 ± 9.4 | 69.8 ± 10.2 | 65.0 ± 9.9 |

| Sex (male/female) | 19/21 | 38/2 | 22/18 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 23.1 ± 3.8 | 20.3 ± 2.6*,# | 23.8 ± 4.0 |

| Smoking, pack-years | 7.1 ± 19.5 | 27.1 ± 17.0*,# | 5.4 ± 8.3 |

| Smoking, cur-, ex-, never- | 5, 5, 30 | 17, 22, 1 | 8, 5, 27 |

| Eosinophil of peripheral blood, % | 3.8 ± 2.1 | 1.6 ± 0.3* | |

| Sputum, % | |||

| neutrophil | 55.2 ± 30.7 | 84.4 ± 12.1* | |

| eosiniphil | 34.7 ± 32.8 | 8.3 ± 6.0* | |

| basophil | 0.58 ± 1.3 | 0.7 ± 1.6 | |

| macrophage | 9.6 ± 11.1 | 6.7 ± 7.3 | |

| Pulmonary function | |||

| %VC, % | 99.7 ± 22.0 | 88.7 ± 25.2 | |

| FVC, L | 2.9 ± 1.0 | 2.6 ± 1.1 | |

| FEV 1.0, L | 1.7 ± 0.8 | 1.4 ± 0.9 | |

| FEV1.0/FVC % pred | 78.5 ± 27.0 | 62.2 ± 22.9 | |

| FEV1.0/FVC, % | 65.9 ± 21.2 | 50.2 ± 13.9 | |

| Medication | |||

| Oral corticosteroids | 20 | 2 | |

| Oral theophyllines | 13 | 15 | |

| Oral expectrants | 2 | 8 | |

| Oral anti-histamines | 2 | 0 | |

| Leukotrienes | 13 | 0 | |

| Tulobuterol patches | 9 | 11 | |

| Inhaled steroids | 13 | 6 | |

| Inhaled β2 agonists | 4 | 4 | |

| Inhaled steroids/β2 agonists | 17 | 12 | |

| Inhaled anticholinergics | 1 | 16 |

*Statistically significance between asthma patients and COPD patients. #Statistically significance between COPD patients and disease control patients.

Protocol

This study is retrospective cohort-study. Pulmonary function tests [% vital capacity (% VC), forced vital capacity (FVC), and forced expiratory volume in 1 sec (FEV1.0)] were measured with a CHESTAC −55V (CHEST MI, Tokyo, Japan) at Gunma University and with a CHESTAC −5500 or −8800 (CHEST MI, Tokyo, Japan) at Jobu Hospital. Pulmonary function in disease control was not measured because this study is retrospective study and measuring pulmonary function was not approved by institute committee. Sputum was obtained after inhaling 3 ml of 3% saline via a nebulizer, and cells were counted. If a patient could not expectorate the sputum, 3 ml of 6% saline were nebulized repeatedly. Defimition of adequate sputum was one in which there were fewer than 20% squamous cells and where viability was <50%.(16) The eosinophil count was determined by Hansel stain.(17) For calculation of the dose of inhaled steroid, fluticasone was assumed to be about twice the strength of budesonide.(18) Exacerbation of asthma and COPD was defined as worsening that required an unscheduled visit to the local doctor, emergency department, or hospital, or else needed treatment with oral or intravenous corticosteroids at least one episode during the past two years.(6,19) The FSSG has been proven to be a useful questionnaire for the assessment of GERD, and it was used to determine the prevalence and symptoms of GERD.(12) This questionnaire is composed of 12 questions (Table 2), which are scored to indicate the frequency of symptoms as follows: never = 0, occasionally = 1, sometimes = 2, often = 3, and always = 4. The cut-off score for diagnosis of GERD was defined as 8 points. The unique feature of the FSSG is that the questions cover both acid regurgitation-related symptoms (questions 1, 4, 6, 7, 9, 10, and 12) and gastric dysmotility-related symptoms (questions 2, 3, 5, 8, and 11). This study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki, and all patients gave informed consent before enrollment. The Human Research Committee of Gunma University and the Human Research Committee of Jobu Hospital for Respiratory Disease both approved this study.

Table 2.

Questions of FSSG*

| Questions | |

|---|---|

| q1 | Do you get heartburn? |

| q2 | Does your stomach get bloated? |

| q3 | Does your stomach ever feel heavy after meals? |

| q4 | Do you sometimes subconsciously rub your chest with your hand? |

| q5 | Do you ever feel sick after meals? |

| q6 | Do you get heartburn after meals? |

| q7 | Do you have an unusual (e.g. burning) sensation in your throart? |

| q8 | Do you feel full while eating meals? |

| q9 | Do some things get stuck when you swallow? |

| q10 | Do you get bitter liquid (acid) coming up into your throat? |

| q11 | Do you burp a lot? |

| q12 | Do you get heartburn if you bend over? |

*FSSG: The frequency of scale for the symptoms of GERD.

Statistics

Data are expressed as the mean (SD). Comparison of parameters between two groups was done by Student’s t test. Comparisons among three groups were done by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. Differences in frequency between regurgitation and dysmotility symptoms were assessed by the chi-square test. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. Comparison of exacerbation number of patients between GERD positive and negative were performed by Fisher’s exact test.

Results

The characteristics of each group are shown in Table 1. Age did not differ among the asthma, COPD, and disease control patients. The body mass index (BMI) of the COPD group was lower than that of the other two groups (p<0.05). Regular treatments given for asthma patients were oral corticosteroids, inhaled steroids/long-acting β2 agonists, oral theophyllines, leukotrines and inhaled steroids. Regular treatments given for COPD patients were inhaled anticholinergics, oral theophilines, inhaled steroids/long acting β2 agonists, inhaled steroids and β2 agonist patches. The prevalence of GERD (detected by the FSSG) was not significantly different among the three groups of asthma patients (10/40, 25%), COPD patients (13/40, 32.5%) and disease control patients (11/40, 27.5%), as shown in Table 3. Among patients with GERD, the COPD patients were older than the asthma and disease control patients (p<0.05). BMI was not statistically different among the groups with GERD. Of the 13 GERD-positive COPD patients, some of the patients received inhaled steroid only or inhaled steroid and long acting β2 agonists patches without inhaled anticholinergics because of having glaucoma or dry mouth due to adverse event of anticholinergics.

Table 3.

Characteristics of asthma, COPD, and disease control having GERD

| Asthma | COPD | Disease control | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of GERD, %, GERD pt/total pt | 25.0, 10/40 | 32.5, 13/40 | 27.5, 11/40 |

| Age, year | 64.2 ± 9.8 | 72.2 ± 7.5* | 64.3 ± 7.5 |

| Sex (male/female) | 2/8 | 13/0* | 4/7 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 22.8 ± 4.4 | 20.7 ± 3.6 | 22.7 ± 2.6 |

| Smoking, pack-years | 10.0 ± 31.6 | 28.9 ± 16.5* | 4.1 ± 8.3# |

| Smoking, cur-, ex-, never- | 0, 0, 10 | 4, 9, 0 | 2, 2, 8 |

| Eosinophil of peripheral blood, % | 3.4 ± 1.1 | 0.3 ± 1.1* | |

| Sputum, % | |||

| neutrophils | 59.1 ± 32.4 | 92.5 ± 5.8* | |

| eosiniphils | 33.1 ± 34.5 | 6.4 ± 5.5* | |

| metachromatic cells (basophils) | 0.29 ± 0.76 | 0 | |

| macrophages | 7.1 ± 7.4 | 1.1 ± 0.85* | |

| Pulmonary functions | |||

| %VC, % | 93.2 ± 18.5 | 67.0 ± 17.1* | |

| FVC, L | 2.1 ± 0.40 | 1.9 ± 0.66 | |

| FEV 1.0, L | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 0.93 ± 0.3* | |

| FEV 1.0% pred, % | 81.9 ± 28.1 | 52.9 ± 16.1 | |

| FEV 1.0/FVC, % | 72.2 ± 22.3 | 50.8 ± 10.1 | |

| Regular use of medication | |||

| Oral corticosteroids | 2 | 0 | |

| Oral theophyllines | 6 | 5 | |

| Oral expectrants | 2 | 2 | |

| Oral anti-histamines | 1 | 0 | |

| Leukotrienes | 4 | 0 | |

| β2 agonist patches | 8 | 3 | |

| Inhaled steroids | 2 | 6 | |

| Inhaled β2 agonists | 0 | 0 | |

| Inhaled steroids/β2 agonists | 6 | 1 | |

| Inhaled anticholinergics | 0 | 8 |

*Statistically significance between asthma patients and COPD patients. #Statistically significance between COPD patients and disease control patients.

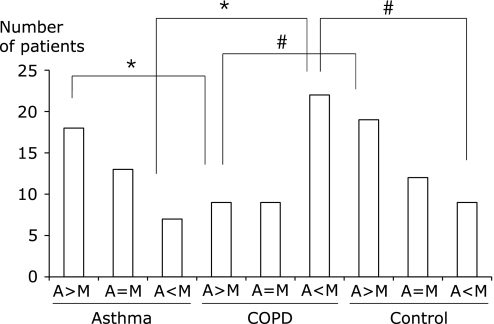

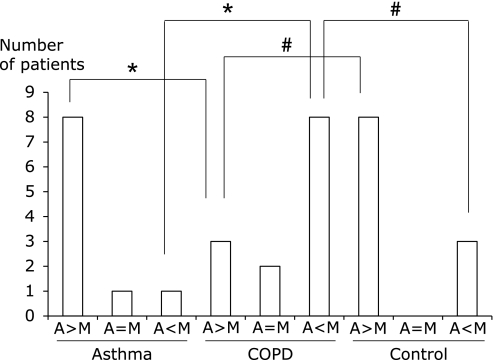

The unique feature of the FSSG is that the questions are divided into those covering acid regurgitation-related symptoms (questions 1, 4, 6, 7, 9, 10, and 12) and those for gastric dysmotility-related symptoms (questions 2, 3, 5, 8, and 11). When regurgitation- and dysmotility-related symptoms were compared among each group, the number of patients showing predominance of regurgitation-related symptoms was higher in the asthma group (p<0.005) and the disease control group (p<0.01) than in the COPD group (Fig. 1). The number of patients showing predominance of dysmotility-related symptoms was higher in the COPD group than in the asthma group (p<0.005) and the disease control group (p<0.01). Among GERD-positive patients, the number of patients showing predominance of regurgitation-related symptoms was higher in the asthma group (p<0.01) and the disease control group (p<0.01) than in the COPD group, while the number with predominance of dysmotility-related symptoms was higher in the COPD group than in the asthma group (p<0.01) or the disease control group (p<0.01), as shown in Fig. 2. Presence GERD evaluated by FSSG was the risk of COPD exacerbation (OR = 4.8, 95% CI 1.25–18.5, p<0.05), however not in asthma (OR = 3.0, 95% CI 0.69–13.1) (Table 4).

Fig. 1.

Chief symptoms of asthma patients (n = 40), COPD patients (n = 40), and disease control patients (n = 40). The total score for acid regurgitation-related symptoms (questions 1, 4, 6, 7, 9, 10, and 12) and the total score for dysmotility-related symptoms (questions 2, 3, 5, 8, and 11) were compared. The number of patients in each group with a higher score for acid regurgitation symptoms (A>M), the same score for both symptoms (A = M), or a higher score for dysmotility symptoms (A<M) was determined. *Significant difference between asthma and COPD. #Significant difference between COPD and disease controls.

Fig. 2.

Chief symptoms in asthma patients (n = 10), COPD patients (n = 13) and disease control patients (n = 11) who were diagnosed as having GERD by the FSSG survey in each group. The total score for acid regurgitation-related symptoms (questions 1, 4, 6, 7, 9, 10, and 12) and the total score for dysmotility-related symptoms (questions 2, 3, 5, 8, and 11) were compared. The number of patients in each group with a higher score for acid regurgitation symptoms (A>M), the same score for both symptoms (A = M), or a higher score for dysmotility symptoms (A<M) was examined. *Significant difference between asthma and COPD. #Significant difference between COPD and disease controls.

Table 4.

Associations between exacerbations and presence of GERD symptoms in asthma and COPD patients

| Exacerbation (+) | Exacerbation (−) | p value | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma GERD (+) | 6 | 4 | |||

| Asthma GERD (−) | 10 | 20 | 0.16 | 3 | 0.69–13.1 |

| COPD GERD (+) | 8 | 5 | |||

| COPD GERD (−) | 9 | 27 | 0.038* | 4.8 | 1.25–18.5 |

The number of patients having a histrory of disease exacerbations (+) or not having a history of exacerbation (−) were compared in presence of GERD (+) symptoms or without presence of GERD (−) symptoms. *Statistically significance between GERD (+) and GERD (−) patients in COPD. Data are presented as odds ratios (ORs) and % 95% confidence interval (CI).

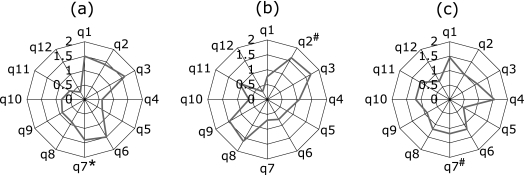

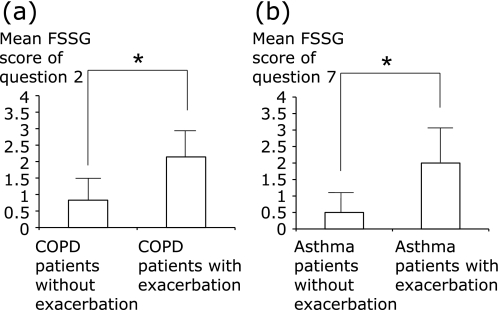

When the scores for each question of patients with GERD were compared among the groups, the mean scores for question 7 (unusual sensation in the throat) was significantly higher in asthma patients and disease control patients with GERD (p<0.01) than in COPD patients with GERD. The mean score for question 2 (bloated stomach) was significantly higher in COPD patients than in disease control patients (p<0.05), but was not significantly different from asthma patients (Figs. 3 a–c). Each data expressed by mean (SD) was shown in Table 5. The score for question 2 was higher in COPD patients with GERD having a history of exacerbation of COPD during the past 2 years than in COPD patients with GERD without having a history of exacerbation (p<0.01) (Fig. 4a). Also, the score for question 7 was higher in asthma patients with GERD having a history of exacerbation during the past 2 years than in asthma patients with GERD without having a history of exacerbation (p<0.01) (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 3.

Mean score for each FFSG question in asthma (a), COPD (b), and disease control (c) patients with GERD. Asthma patients (n = 10), COPD patients (n = 13), and disease control patients were diagnosed as having GERD by the FSSG survey in each group. Vertical bars from 0 to 2 show the mean score for each question. *Significant difference between asthma and COPD. #Significant difference between COPD and disease controls.

Table 5.

Scores for questions of FSSG on patients with GERD

| FSSG question number | Asthma with GERD | COPD with GERD | Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| q1 | 1.0 (1.1) | 0.8 (1.1) | 1.4 (1.3) |

| q2 | 1.5 (0.8) | 1.6 (1.0)# | 1.0 (1.3) |

| q3 | 1.3 (1.4) | 1.7 (1.0) | 1.1 (1.2) |

| q4 | 0.8 (0.8) | 1.1 (0.8) | 1.6 (1.2) |

| q5 | 0.5 (0.5) | 0.8 (0.2) | 0.6 (1.0) |

| q6 | 1.3 (1.5) | 0.7 (1.0) | 1.2 (1.3) |

| q7 | 1.5 (1.4)* | 0.5 (1.1) | 1.5 (1.5)# |

| q8 | 0.5 (0.8) | 1.5 (1.1) | 1.5 (1.4) |

| q9 | 0.7 (0.8) | 1.3 (0.8) | 0.9 (1.2) |

| q10 | 0.7 (0.8) | 0.5 (0.7) | 1.2 (1.4) |

| q11 | 0.5 (0.5) | 1.1 (0.9) | 1.1 (1.4) |

| q12 | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.2 (0.4) | 1.2 (0.4) |

FSSG was composed by 12 questions (q1 to q12), and each score was indicated mean (SD) in asthma with GERD (n = 10), COPD with GERD (n = 13) and disease control with GERD (n = 11). Statistically significance between asthma and COPD is indicated *p<0.05. Statistically significance between COPD and disease control is indicated #p<0.05.

Fig. 4.

The mean scores for questions 2 and question 7 in COPD or asthma patients with GERD having a history of disease exacerbation vs patients without having a history of exacerbation. The scores of COPD patients with GERD for question 2 (bloated stomach) (a). Scores are compared between COPD patients with GERD having a history vs without having a history of exacerbation. Scores of asthma patients with GERD for question 7 (unusual sensation of the throat) (b). Scores are compared between asthma patients with GERD having a history vs without having a history of exacerbation. *Significant difference between groups.

Discussion

A previous survey using the FSSG revealed that the prevalence of GER was 27.4% among asthma patients,(20) and that its prevalence was higher among COPD patients (26.8%) than among age-matched healthy controls (12.5%).(21) The prevalence of GERD detected in the present study was similar to that in other studies using the FSSG, but the prevalence of GERD in the control group was higher in the present study (32.5% vs 27.5%) compared with a previous study.(21) A previous FSSG survey of metabolic syndrome patients, revealed that hypertension or hyperlipidemia were independent risk factors for GERD and metabolic syndrome patients showed high score of FSSG.(22) A possible reason for the different prevalences in the control groups was different background factors, i.e., healthy versus diseased subjects including those with hypertension and hyperlipidemia, and also this was the one of the reason that no statistical difference in prevalance among asthma, COPD and control groups in present study.

Dysmotility-related symptoms were prominent in the COPD patients. A survey using the Rome II criteria for irritable bowel syndrome showed that 14% of COPD patients fulfilled these criteria.(23) A physiological study using manometry showed a 35% decrease of peristalsis in COPD patients.(24) To our knowledge, there has only been this study about esophageal motility, and there have been no studies of intestinal peristalsis in COPD patients. A decrease of lower esophageal sphincter pressure is related to the mechanism of GER in both asthma and COPD patients,(25–27) while dysmotility from the esophagus to intestines seemed to contribute to GER symptoms in COPD. Dysmotility symptoms are frequently induced by rather functional dyspepsia (FD) than GERD. Rome III consensus for diagnosis of FD needs the absence of organic disorder, such as esophagitis, gastric atrophy or erosive gastroduodnal leisions on endoscopy.(28) Present study was questionnaire based survey, and did not include the endoscopic examination. Therefore it was difficult to discriminate between GERD and FD patients. The FSSG contains questions about dysmotility symptoms, in addition to acid-reflux-related symptoms, allowing it to detect GERD symptoms widely. However, the FSSG was inferior to QUEST for the diagnosis of reflux esophagitis in distinguishing between GERD and other condition, such as FD, gastric ulcer (GU) and duodenal ulcer (DU).(29) Further analysis is needed to proportion of FD in COPD patients.

In asthma patients, the typical symptom detected by the FSSG was an unusual sensation in the throat. Bloated stomach also showed a high score, but it was not statistically different from the other items. There is an increase of tonsillitis, pharyngitis, and laryngitis among respiratory tract diseases in patients with GERD, and GERD is also considered to play a role in 55% of hoarseness.(2,30) Possible mechanisms leading to an unusual sensation in the throat are direct acid reflux or acidic gas reflux.(31) Another mechanism is stimulation of esophageal or laryngeal sensory nerves by gastric acid, because some sensory nerves from these sites terminate in the same region of the central nervous system.(32) The limitation of this result is that factors of patients in this study might affect the unusual sensation in throat. Medications such as β2 agonists and oral theophilines might aggravate GERD, and use of inhaled steroids might have been a cause of ”unusual sensation in throat”.(33) Eosinophil ratio was actually high in asthma patients, and several patients received oral corticosteroids which indicated those patients were severe asthma, and this might affect on unusual sensation in the throat in asthma patients.

In COPD patients, the typical symptom detected by the FSSG was bloated stomach. As mentioned above, dysmotility of the esophagus has been speculated to have an association with COPD,(23) but there has not been enough investigation. It is known that the severity of atrophic gastritis increases with a longer duration of COPD, as well as with the severity of hypoxia and bronchial obstruction.(34) Ventilation affects both gastric mucosal blood flow and gastric mucosal pH.(35) Thus, COPD can influence the mucosa and blood flow of the stomach, and changes of the mucosal integrity or blood flow may have an effect on GER.

Recently published longitudinal study showed that a history of gastroesophageal reflux or heartburn is associated with frequent-exacerbation phenotype in COPD patients.(36) Patients who had GER symptoms of reflux or heartburn had significantly more hospitalizations related to their COPD.(6) In present study, COPD patients had more dysmotility symptoms than reflux or heartburn symtoms, and presence of GERD evaluated by total score of FSSG was the risk of COPD exacerbations. Therefore, dysmotility to esophagus to intestine possibly affects COPD exacerbation. In asthma patients, presence of GERD evaluated by total score of FSSG did not affect the asthma exacerbations. Asthma patients had more reflux symptoms than dysmotility symptoms, and FSSG total score was inferior to QUEST for the dections of reflux symptoms.(29) This might affect the negative result for the detecting an increased risk of asthma exacerbation by FSSG. The scores for questions 2 and 7 were higher in GERD patients with a history of exacerbation of asthma or COPD than in GERD patients without a history of exacerbation. These questions were useful for detecting an increased risk of exacerbation. Previous reviews have indicated an association of GERD with the risk of exacerbation of asthma and COPD, but the potential effect of anti-reflux therapy, (PPIs, etc.) on this relationship has not been determined.(7,37) Multi-drug therapy may be important in asthma and COPD patients with GERD. In conclusion, dysmotility-related symptoms were common in COPD patients, and useful questions from the FSSG were an ”unusual sensation in the throat” for asthma patients or ”bloated stomach” for COPD patients. GERD is considered to be a risk factor for the exacerbation of COPD, but the efficacy of PPI therapy is limited. The efficacy of PPIs may differ between regurgitation-related symptoms and dysmotility-related symptoms in asthma patients and COPD patients with GERD.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank for Fueki M., a director of Jobu Hospital, and medical staffs of Gunma University and Jobu hospital for assistant the study. This work was not supported by any grant. None of the authors have any conflict of interest.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author’s Contributions

Shimizu Y. MD., PhD and head of internal medicine of Jobu Hospital for Respiratory Disease designed the study, collected the datas, analysed the datas, and wrote the manuscript. Dobashi K. MD., PhD and Prof. designed the study and collected the datas, Kusano M. MD., PhD and Associate Prof. gave useful suggestions for FSSG and GERD, and Mori M. MD., PhD and Prof. gave useful suggestions for the design of this study.

References

- 1.Harding SM. Recent clinical investigations examining the association of asthma and gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Med. 2003;115:39S–44S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malagelada JR. Review article: supra-oesophageal manifestations of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19 Suppl:43S–48S. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-0673.2004.01836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carlsson R, Galmiche JP, Dent J, Lundell L, Frison L. Prognostic factors influencing relapse of oesophagitis during maintenance therapy with antisecretory drugs: a meta-analysis of long-term omeprazole trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:473–482. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.00167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimizu Y, Dobashi K, Kobayashi S, et al. High prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease with minimal mucosal change in asthmatic patients. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2006;209:329–336. doi: 10.1620/tjem.209.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Thoracic Society Lung function testing: selection of reference values and interpretative strategies. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144:1202–1218. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.5.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rascon-Aguilar IE, Pamer M, Wludyka P, et al. Role of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms in exacerbations of COPD. Chest. 2006;130:1096–1101. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.4.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galmiche JP, Zerbib F, Bruley des Varannes S. Review article: respiratory manifestations of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:449–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Lung Association Asthma Clinical Research Centers. Mastronarde JG, Anthonisen NR, Castro M, et al. Efficacy of esomeprazole for treatment of poorly controlled asthma. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1487–1499. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sasaki T, Nakayama K, Yasuda H, et al. A randomized, single-blind study of lansoprazole for the prevention of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1453–1457. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fass R, Sifrim D. Management of heartburn not responding to proton pump inhibitors. Gut. 2009;58:295–309. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.145581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fass R. Proton pump inhibitor failure—what are the therapeutic options? Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:S33–S38. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kusano M, Shimoyama Y, Sugimoto S, et al. Development and evaluation of FSSG: frequency scale for the symptoms of GERD. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:888–891. doi: 10.1007/s00535-004-1417-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Locke GR, 3rd, Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ., 3rd Prevalence and clinical spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1448–1456. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Global Initiative for Asthma . Bethesda: National institute of Health; 2003. Global strategy for Asthma managenebt and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Global Initiative for Chronic obstructive Lung Disease . Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carpagnano GE, Resta O, Ventura MT, et al. Airway inflammation in subjects with gastro-oesophageal reflux and gastro-oesophageal reflux-related asthma. J Intern Med. 2006;259:323–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saito Y, Tokita N, Takayama T, Hasegawa M. Introduction of the Hansel stain. Jibiinkoka. 1970;42:931–934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson M. The anti-inflammatory profile of fluticasone propionate. Allergy. 1995;50 Suppl:11S–14S. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1995.tb02735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bjermer L, Bisgaard H, Bousquet J, et al. Montelukast and fluticasone compared with salmeterol and fluticasone in protecting against asthma exacerbation in adults: one year, double blind, randomised, comparative trial. BMJ. 2003;327:891. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7420.891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takenaka R, Matsuno O, Kitajima K, et al. The use of frequency scale for the symptoms of GERD in assessment of gastro-oesophageal reflex symptoms in asthma. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2010;38:20–24. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Terada K, Muro S, Sato S, et al. Impact of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease symptoms on COPD exacerbation. Thorax. 2008;63:951–955. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.092858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moki F, Kusano M, Mizuide M, et al. Association between reflux oesophagitis and features of the metabolic syndrome in Japan. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1069–1075. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Niklasson A, Strid H, Simrén M, Engström CP, Björnsson E. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:335–341. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282f2d0ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kempainen RR, Savik K, Whelan TP, Dunitz JM, Herrington CS, Billings JL. High prevalence of proximal and distal gastroesophageal reflux disease in advanced COPD. Chest. 2007;131:1666–1671. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harding SM, Guzzo MR, Richter JE. 24-h esophageal pH testing in asthmatics: respiratory symptom correlation with esophageal acid events. Chest. 1999;115:654–659. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.3.654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zerbib F, Guisset O, Lamouliatte H, Quinton A, Galmiche JP, Tunon-De-Lara JM. Effects of bronchial obstruction on lower esophageal sphincter motility and gastroesophageal reflux in patients with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:1206–1211. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200110-033OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Casanova C, Baudet JS, del Valle M, et al. Increased gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in patients with severe COPD. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:841–845. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00107004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tack J, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, et al. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1466–1179. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Danjo A, Yamaguchi K, Fujimoto K, et al. Comparison of endoscopic findings with symptom assessment systems (FSSG and QUEST) for gastroesophageal reflux disease in Japanese centres. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:633–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koufman JA. The otolaryngologic manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD): a clinical investigation of 225 patients using ambulatory 24-hour pH monitoring and an experimental investigation of the role of acid and pepsin in the development of laryngeal injury. Laryngoscope. 1991;101:1–78. doi: 10.1002/lary.1991.101.s53.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smit CF, van Leeuwen JA, Mathus-Vliegen LM, et al. Gastropharyngeal and gastroesophageal reflux in globus and hoarseness. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;126:827–830. doi: 10.1001/archotol.126.7.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Canning BJ, Mazzone SB. Reflex mechanisms in gastroesophageal reflux disease and asthma. Am J Med. 2003;115:45S–48S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00192-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harding SM. Acid reflux and asthma. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2003;9:42–45. doi: 10.1097/00063198-200301000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fedorova TA, Spirina LIu, Chernekhovskaia NE, et al. The stomach and duodenum condition in patients with chronic obstructive lung diseases. Klin Med (Mosk) 2003;81:31–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bocquillon N, Mathieu D, Neviere R, Lefebvre N, Marechal X, Wattel F. Gastric mucosal pH and blood flow during weaning from mechanical ventilation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:1555–1561. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.5.9901018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hurst JR, Vestbo J, Anzueto A, et al. Susceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1128–1138. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gaude GS. Pulmonary manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Ann Thorac Med. 2009;4:115–123. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.53347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]