Abstract

Context:

Clinical evaluation of gingivitis and/or periodontitis does not predict the progression or remission of the disease. Due to this diagnostic constraint, clinicians assume that the pathology has an increased risk of progression and plan treatments, despite the knowledge that all inflamed sites are not necessarily progressing. Extensive research has been carried out on gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) components that might serve as potential diagnostic markers for periodontitis. Among them alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels in GCF has shown promise as a diagnostic marker.

Aim:

This study compares the levels of GCF alkaline phosphatase in patients with chronic periodontitis before and after scaling and root planing.

Materials and Methods:

This study is an in vivo longitudinal study conducted on twenty patients with localized periodontitis. The GCF was collected from the affected site prior to scaling and root planing and ALP level estimated. The probing depth and plaque index at the site were also measured for correlation. Patients were recalled after 7, 30, and 60 days for reassessment.

Results:

The GCF ALP values showed a sustained, statistically significant decrease after treatment. There was a positive correlation with probing depth but not with plaque index measured at each interval.

Conclusion:

The assessment of level of periodontal disease and effect of mechanical plaque control on the progression and regression of the disease can be evaluated precisely by the corresponding GCF ALP levels. Thus, alkaline phosphatase level is not only a biomarker for the pathology but also an indicator of prognosis of periodontitis.

Keywords: Alkaline phosphatase, gingival crevicular fluid, periodontal therapy, periodontitis, scaling and root planing

INTRODUCTION

Periodontitis is an inflammatory condition affecting the supporting structures of the tooth namely the periodontal ligament, cementum, and alveolar bone. Bacterial plaque is one of the main etiological factors in the initiation and promotion of periodontal diseases.[1] Traditionally, the diagnosis of periodontal disease is established by clinical and radiographic parameters. These techniques are deficient in identifying and measuring the progression or regression taking place in the previously diseased sites and in the newly developing disease sites.[2,3] Altered enzymatic action, both at cellular and sub-cellular levels influence the disease process. The measurement of the enzymes can provide valuable diagnostic and prognostic information.[4,5]

Periodontal disease is considered to progress in periods of disease activity, followed by periods of quiescence. For effective treatment, it is important to know whether the disease is in an active phase or not. Even in apparent health, there are inflammatory changes in gingiva at the molecular level due to the exposure to the oral environment.[6,7]

The present trend in clinical medicine leans towards the use of non invasive procedures that determine the changes in salivary constituents to diagnose several diseases. The potential diagnostic importance of gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) was recognized more than 60 years ago.[8] Analysis of the gingival crevicular fluid provides a noninvasive method of studying the host response factors in the periodontium during the initial diagnosis and treatment.[9,10] Binder et al.[11] demonstrated a strong positive relationship between the levels of the enzyme in GCF and previous disease activity. GCF contains inflammatory products, bacterial products, and products of tissue break down. Thus, examination of GCF is an ideal method of evaluating the inflammatory tissue destruction and bacterial activity associated with periodontal disease.

The objective of this study is to compare the gingival crevicular fluid alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels before and after scaling and root planning in patients with chronic periodontitis. It is postulated that this could serve as a prognostic predictor, as an adjunct to the routine methods used for determination of the disease activity and has a direct influence on the diagnosis, therapy, and prognosis of periodontitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient selection

Twenty patients were randomly selected from the out patients pool of the department of periodontics, who met the following criteria.

Adult male/female patient between 20 and 50 years.

Patients with chronic localized periodontitis having probing pocket depth of 4–6 mm.

No history of antibiotic, antimicrobial, and/or anti-inflammatory drug usage for last 6 months.

No history of any systemic diseases, which could influence the development, course and prognosis of periodontal disease and/or periodontal therapy.

No developmental or anatomic defects detrimental to periodontal treatment prognosis.

No furcation involvement.

No history of periodontal treatment for last one year.

No personal habits that can influence periodontal health and treatment efficiency.

No restoration or prosthesis on the selected tooth.

Site selection

The selection of the site for the collection of gingival crevicular fluid was done one day prior to treatment, to avoid possible contamination of the crevicular fluid with blood after probing. Pocket depth was measured using Williams graduated periodontal probe, held parallel to the long axis of tooth from the free gingival margin to the base of the pocket.

Plaque assessment and isolation

Disclosing agent was applied for one minute on the selected site. This was done for the purpose of motivating the patient. Plaque index (Sillness and Loe) was recorded. The selected site was isolated with sterile cotton and compressed air was used to gently dry the quadrant to prevent contamination.

Sample collection

All GCF samples were collected in the forenoon (at same time, of the day) (between 10 and 11 AM) to allow for the circadian variation seen in GCF volume.[12] A calibrated volumetric micropipette of 5 μL capacity was introduced into the periodontal pocket of the selected site for collection of gingival crevicular fluid by Brill technique.[9] The sample was collected for 20 min. The collected sample was then transferred to a sterilized plastic vial with the help of air-spray. The vial was frozen to –20°C until the sample was transported to the laboratory for analysis.

Treatment

A thorough scaling and root planing was then carried out with ultrasonic scalers and Gracey curettes by single operator. Oral hygiene instructions were given to the patient, which included appropriate brushing technique. The patients were recalled on the 7th, 30th, and 60th day after scaling and root planing. The gingival crevicular fluid was collected and clinical parameters were recorded in the similar manner at each recall periods. No periodontal treatment was provided in the recall visits. Only oral hygiene instructions were given to the patients.

Biochemical analysis[13]

Enzyme (kinetic) analysis of the alkaline phosphatase level in GCF was done using a spectrophotometer. The rate of formation of p-Nitrophenol is measured as an increase in absorbance of 405 nm wavelength light which is proportional to the alkaline phosphatase activity in the sample. The final results were expressed as corrected optical densities or enzyme units, where 1 unit is equal to 1 μmol p-nitro phenylphosphate converted to p-nitro phenol plus inorganic phosphate per minute at the pH and temperature indicated for alkaline phosphate.

The measured values for Total GCF ALP, probing depth and plaque index were tabulated and statistically analyzed. A P<0.05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

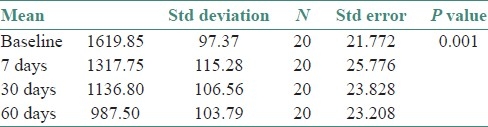

Since the GCF ALP levels were showing a uniform distribution, parametric ANOVA repeated measure was utilized for analysis. The statistical test compared all the groups together [Table 1] and also did pairwise comparison [Table 2]. Total alkaline phosphatase levels in gingival crevicular fluid were found to be highest in baseline patients. There was a statistically significant decrease between each of the sampled groups in the duration of the study (baseline, 7th, 30th, and 60th day) at P≤0.001.

Table 1.

ANOVA comparing GCF alkaline phosphatase values

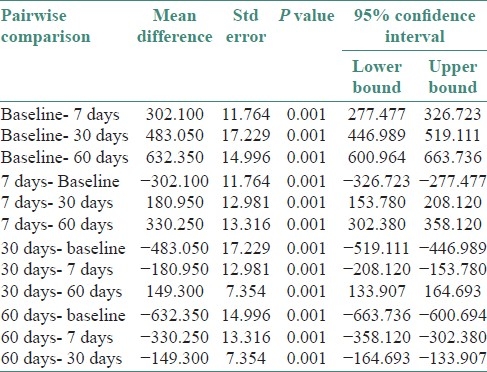

Table 2.

Pairwise inter group comparison of GCF ALP levels

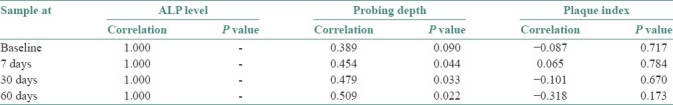

Since variables such as probing depth and plaque index were not in uniform distribution nonparametric Spearman's Rank Correlation test was used to correlate between these variables and GCF total ALP levels. Alkaline phosphatase levels were found to be positively correlated with probing depth. However, there was no correlation found between alkaline phosphatase levels and plaque index P≤0.05 [Table 3].

Table 3.

Spearman rank correlation between GCF ALP levels, probing depth and plaque index

DISCUSSION

Periodontal diseases alter the biochemical constituents in both tissue and blood through metabolic changes. Tissue destruction is seen as the consequence of bacterial interaction in periodontal disease, which is due to host cells (mainly polymorphonuclear leukocytes) releasing their granular enzymes (lysozyme, β-glucaronidase) that are capable of attaching to all extracellular matrix components that seem to play an important role in the tissue damage.[7,14,15]

GCF is an exudate from the microcirculation around the inflamed periodontium and gingiva. It picks up enzymes and other molecules that participate in the disease process, immune mechanism, bacterial products, as well as products of cell and tissue destruction.[8,9] The main cells that contribute to the constituents of GCF are polymorphonuclear lymphocytes, macrophages, and plasma cells.[10] Unlike serum and saliva that are the commonly used sources for assessment of biomarkers, GCF is site specific, conveniently sampled, and contains components derived from both the host and the bacteria. Conversely only extremely small volume of fluid is available from a single site, and so GCF needs highly sensitive techniques for quantitative analysis.[11,13,16,17] The composition and possible role of GCF in oral defense mechanisms were elucidated by the work of Waerhaug,[3] Brill and Krasse.[9] Gustafsson and Nilsson[15] found the presence of fibrinolytic activity in GCF.

Several other substances have been found in GCF, collected from sites with inflammatory periodontal disease. These constituents include physiologically active substances and enzymes such as prostaglandins,[18,19] collagenase,[20] hydroxyproline,[21] β-glucuronidase,[22] lactate dehydrogenase,[22] glycosaminoglycans,[23] aspartate aminotransferase,[24] and alkaline phosphatase (ALP).[17,19,25]

Ishikawa and Cimasoni[26] first recognized the potential of alkaline phosphatase as an important biochemical component of GCF in 1970. The sources of ALP are polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNL),[14] bacteria within the dental plaque[27] and osteoblasts and fibroblast cells.[16] Binder et al.[11] demonstrated a strong positive relationship between the levels of alkaline phosphatase in GCF and previous disease activity. The GCF serum ratio for clinically healthy periodontal tissues ranged from 6:1 to 12:1, which implies that the enzyme is locally produced within the periodontium.[28] Thus, gingival crevicular fluid ALP levels from periodontal pockets can be taken as indicative for active periodontal tissue destruction. Chapple et al. noted that total GCF ALP levels increased before increases in the gingival index and appears to be a good marker of gingival inflammation. They stated that majority of ALP in GCF is of PMNL origin[29] Nakashima et al. 1994 found in their study that total amounts of ALP are significantly higher in periodontitis as compared to healthy and gingivitis sites.[19]

There are abundant PMNL in the site of periodontal inflammation and they are a prime source for GCF ALP.[13,29,30] The decrease in the inflammation as a result of the mechanical plaque control methods such as scaling and root planing has resulted in the statistically significant decrease of GCF ALP values in the study. This is also reflected in the decreased pocket depth as seen by the positive correlation to probing depth. Ishikawa and Cimasoni also found the positive correlation between alkaline phosphatase levels and probing depth.[26]

The lack of correlation of ALP levels with the plaque index may be attributed to the fact that even though the plaque bacteria are a source of alkaline phosphatase the percentage contribution to the total GCF ALP levels is not significant.[27] Plaque assays have suggested that bacterial ALP contribute less than 20% to total ALP content of GCF.[29] This suggests that the total ALP level reflects the state of the periodontium more accurately in disease and healing and is not significantly affected by the external bacterial factors in plaque.[17,25,29,30]

CONCLUSION

Total alkaline phosphatase levels in gingival crevicular fluid can be used as a diagnostic biomarker to assess the health and pathology of the periodontium. It can be used in early detection of periodontal changes and can assess the efficacy and prognosis of treatment. However, since there are multiple sources of ALP further studies on evaluation of ALP from single source (isoenzyme studies) may increase the diagnostic value of alkaline phosphatase level as a disease maker.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Offenbacher S. Periodontal diseases: Pathogenesis. Ann Periodontol. 1996;11:821–78. doi: 10.1902/annals.1996.1.1.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zappa U. Histology of the periodontal lesion: Implications for diagnosis. Periodontol 2000. 1995;7:22–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1995.tb00034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waerhaug J. Gingival pocket Anatomy, pathology, deepening and elimination. Odontol Tidskr. 1952;60(Suppl 1):1–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Page RC. Host response tests for diagnosing periodontal diseases. J Periodontol. 1992;19:43–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.1992.63.4s.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fine DH, Mandel ID. Indicators of periodontal disease activity: An evaluation. J Clin Periodontol. 1986;13:533–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1986.tb01502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fine DH. Incorporating new technologies in periodontal diagnosis into training programs and patient care: A critical assessment and a plan for the future. J Periodontol. 1992;63(4 Suppl):383–93. doi: 10.1902/jop.1992.63.4s.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Dyke TE, Lester MA, Shapira L. The role of the host response in periodontal disease progression. Implications for future strategies. J Periodontol. 1993;64(8 Suppl):792–806. doi: 10.1902/jop.1993.64.8s.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cimasoni G. Crevicular fluid updated. (1-152).Monogr Oral Sci. 1983;12:3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brill N, Krass B. The passage of tissue fluid into the clinically healthy gingival pocket. Acta Odontol Scand. 1958;16:223–45. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Embery G, Waddington R. Gingival crevicular fluid: Biomarkers of periodontal tissue activity. Adv Dent Res. 1994;8:329–36. doi: 10.1177/08959374940080022901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Binder TA, Goodson JM, Socransky SS. Gingival fluid levels of acid and alkaline phosphatase. J Periodontal Res. 1987;22:14–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1987.tb01534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bissada NF, Scahaffer EM, Haus E. Cicardian periodicity of human crevicular fluid flow. J Periodontol. 1967;38:36–40. doi: 10.1902/jop.1967.38.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malhotra R, Grover V, Kapoor A, Kapur R. Alkaline phosphatase as a periodontal disease marker. Indian J Dent Res. 2010;21:531–6. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.74209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohn ZA, Hirsch JG. The isolation and properties of specific cytoplasmic granules of rabbit polymorphonuclear lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1960;112:983–1004. doi: 10.1084/jem.112.6.983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gustafsson GT, Nilsson IM. Fibrinolytic activity in fluid from the gingival crevice. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1961;106:277–80. doi: 10.3181/00379727-106-26308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cabrini RL, Caranza FA. Histochemical study on alkaline phosphatase in normal gingivae varying the pH and substrate. J Dent Res. 1951;30:28–32. doi: 10.1177/00220345510300011101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chapple IL, Mathews JB, Thorpe GH, Glenwright HD, Smith JM, Saxby MS. A new ultrasensitive chemiluminiscent assay for the site-specific quantification of alkaline phosphatase in gingival crevicular fluid. J Periodontal Res. 1993;28:266–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Offenbacher S, Odle BM, Van Dyke TE. The use of crevicular fluid prostaglandin-E2 levels as a predictor of periodontal attachment loss. J Periodontal Res. 1986;21:101–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1986.tb01443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakashima K, Roehrich N, Cimasoni G. Osteocalcin, prostaglandin E2 and alkaline phosphatase in gingival crevicular fluid: Their relations to periodontal status. J Clin Periodontol. 1994;21:327–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1994.tb00721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Golub LM, Seigal K, Ramamurthy NS, Mandel ID. Some characteristics of collagenase activity in gingival crevicular fluid and its relationship to gingival disease in humans. J Dent Res. 1976;55:1049–57. doi: 10.1177/00220345760550060701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Svanberg GK. Hydroxyproline determination in serum and gingival crevicular fluid. J Periodontal Res. 1987;22:133–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1987.tb01552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lamster IB, Vogel RJ, Hartley LJ, DeGeroge CA, Gordon JM. Lactate dehydrogenase, β glucaronidase and aryl sulphatase in gingival crevicular fluid associated with experimental gingivitis in man. J Periodontol. 1985;56:139–47. doi: 10.1902/jop.1985.56.3.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Last KS, Stanberg JB, Embery G. Glycosaminoglycans in human crevicular fluid as indicator of active periodontal disease. Arch Oral Biol. 1985;30:275–81. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(85)90045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Persson GR, DeRouen TA, Page RC. Relationship between levels of aspartate aminotransferase in gingival crevicular fluid and gingival inflammation. J Periodontal Res. 1990;25:17–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1990.tb01203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perinetti G, Paolantonio M, Feminella B, Serra E, Spoto G. Gingival crevicular fluid alkaline phosphatase activity reflects periodontal healing/recurrent inflammation phases in chronic periodontitis patients. J Periodontol. 2008;79:1200–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ishikawa I, Cimasoni G. Alkaline phosphatase in human gingival fluid and its relation to periodontitis. Arch Oral Biol. 1970;15:1401–4. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(70)90032-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bowen WH. Phosphatase in microorganisms cultured from carious dentin and calculus. J Dent Res. 1961;40:571–7. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daltanban O, Saygun I, Bal B, Balos K, Serbar M. Gingival crevicular fluid alkaline phosphatase levels in post menopausal women: Effects of phase I periodontal treatment. J Periodontol. 2006;77:67–72. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.77.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chapple IL, Socransky SS, Dibart S, Glenwright HD, Matthews JB. Chemiluminescent assay of alkaline phosphatase in human gingival crevicular fluid: Investigations with an experimental gingivitis model and studies on the source of the enzyme within crevicular fluid. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:587–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1996.tb01829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chapple IL, Glenwright HD, Mathew JB, Thorp GH, Lumley PJ. Site-specific alkaline phosphatase levels in gingival crevicular fluid in health and gingivitis: Cross-sectional studies. J Clin Periodontol. 1994;21:409–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1994.tb00738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]