Abstract

Ginseng roots (Panax ginseng CA Meyer) have been used traditionally for the treatment, especially prevention, of various diseases in China, Korea, and Japan. Both experimental and clinical studies suggest ginseng roots to have pharmacological effects in patients with life-style-related diseases such as non-insulin-dependent diabetic mellitus, atherosclerosis, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension. The topical use of ginseng roots to treat skin complaints including atopic suppurative dermatitis, wounds, and inflammation is also described in ancient Chinese texts; however, there have been relatively few studies in this area. In the present paper, we describe introduce the biological and pharmacological effects of ginsenoside Rb1 isolated from Red ginseng roots on skin damage caused by burn-wounds using male Balb/c mice (in vivo) and by ultraviolet B irradiation using male C57BL/6J and albino hairless (HR-1) mice (in vivo). Furthermore, to clarify the mechanisms behind these pharmacological actions, human primary keratinocytes and the human keratinocyte cell line HaCaT were used in experiments in vitro.

1. Introduction

The oral administration of red ginseng root (P. ginseng) extracts has long been used to treat various diseases, including liver and kidney dysfunction, hypertension, non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, and postmenopausal disorders, in China, Korea, and Japan. Topical applications have also been used for atopic suppurative dermatitis, wounds, and skin inflammation. The materials for Korean red ginseng products are selected from among ginseng roots (Panax ginseng CA Meyer) carefully cultivated in well-fertilized field for 6 years and then steamed and dried in the sun six times. The red ginseng extract produced by Korea Ginseng Corporation (Taejon, Korea) is dried and powdered by freezing prior to use. In this paper, we introduce the biological and pharmacological effects of ginsenoside Rb1 isolated from red ginseng roots on skin damage in mice.

2. Effects of Ginsenoside Rb1 on Burn Wound Healing in Mice

Burns and wounds initially induce coagulative necrosis and cause the formation of a scar. Macrophages migrate to an injured area to kill invading organisms and produce cytokines that recruit other inflammatory cells responsible for the diverse effects of inflammation [1, 2]. Angiogenesis in the injured area is closely associated with the process of wound healing [3]. Moreover, growth factors and cytokines are central to the wound-healing process [4–6]. Thus, the burn wound-healing process is complex, involving inflammatory factors, including monocyte migration and cytokine production, and growth factors and angiogenesis during reepithelialization. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) plays an important role in skin tissue repair through angiogenesis during the healing of burn wounds [4, 7, 8]. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that chemokines including macrophage inflammatory protein-1α(MIP-1α) and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) are expressed at high levels in murine full-thickness dermal wounds at times preceding and coinciding with maximal macrophage infiltration [9–12]. Interleukin 1-β (IL-1β) is also known to be released from monocyte-derived macrophages during inflammation and stimulates VEGF expression in endothelial cells, keratinocytes, synovial fibroblasts, and colorectal carcinoma cells [13–16]. IL-1β gene expression was reported to be upregulated in MCP-1-treated human monocytes [17]. Trautmann et al. [18] found that the expression of MCP-1 of macrophage and keratinocyte origin correlated with the accumulation of mast cells during wound healing. Weller et al. [19] reported that mast cell activation and histamine release were required for wound healing. Numata et al. [20] showed that the accelerated wound-repair activity of histamine was mediated by the activity of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), which leads to angiogenesis, and macrophage recruitment in the wound-healing process. Thus, the process of wound repair is thought to be closely associated with the network systems among various cells such as keratinocytes, fibroblasts, macrophages and mast cells, and might be modulated by interactions among chemokines, cytokines, growth factors, and related biofactors secreted from these cells.

The genus Panax derives its name from the Greek words pan (all) and akos (healing). In 1988, Kanzaki et al. [21] reported that an orally administered red ginseng root extract stimulated the repair of intractable skin ulcers in patients with diabetes mellitus and Werner's syndrome in clinical trials. Morisaki et al. [22] showed that the local administration of ginseng saponins markedly improved wound healing in diabetic and aging rats. Sengupta et al. [23] reported that ginsenoside Rg1 promoted functional angiogenesis into a polymer scaffold (in vivo) and the proliferation and chemoinvasion of tube-like capillary formation by human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) through enhanced expression of nitric oxide synthetase, phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase, and the Akt pathway (in vitro). Conversely ginsenoside Rb1 inhibited the earliest step in angiogenesis, the chemoinvasion of HUVECs [23]. Furthermore, Choi [24] reported that ginsenoside Rb2 improved wound healing through its facilitating effects on epidermal cell proliferation, by upregulating the expression of proliferation-related factors. However, Sato et al. [25] found that the intravenous administration of ginsenoside Rb2 inhibited metastasis to the lung by inhibiting tumor-induced angiogenesis in B16-BL6 melanoma-bearing mice. Thus, there are perplexing contradictions in the reported effects of various ginseng saponins on angiogenic activity as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Effects of various ginseng saponins on angiogenesis.

| Effects of ginsenoside Rb2 (100 μg/mouse, iv) on tumor-induced angiogenesis in B16-BL6 melanoma-inoculated mice (in vivo) Ginsenoside Rb2 showed antiangiogenesis [25]. |

|

|

| |

| Effects of ginsenoside Rb2 (100 μg/mouse, iv and 300 μg/mouse, po), 20(R)Rg3 (100 μg/mouse, iv and 300 μg/mouse, po), and 20(S)Rg3 (100 μg/mouse, iv and 300 μg/mouse, po) on tumor-induced angiogenesis in B16-BL6 melanoma-inoculated mice (in vivo). Ginsenoside Rb2, 20(R)Rg3 and 20(S)Rg3, showed antiangiogenesis [40]. |

|

|

| |

| Effects of the total saponin fraction (10–100 μg/mL) on tube formation by HUVECs (in vitro). The total saponin fraction enhanced angiogenesis [22]. |

|

|

| |

| Effects of ginsenoside Rg1 (10 μM) and Rb1 (10 μM) on angiogenesis in scaffold implants in mice (in vivo). Effects of Rg1 (125 nM) and Rb1 (125 nM) on chemoinvasion in HUVEC (in vitro). Ginsenoside Rg1 enhanced angiogenesis, and ginsenoside Rb1 showed antiangiogenesis in the earliest stage [23]. |

|

|

| |

| Effects of ginsenoside Re (10–100 μg/mL) on angiogenesis in HUVECs (in vitro). Effects of Re (70 μg/extracellular matrix) on angiogenesis in extracellular matrix-implanted rats (in vivo). Ginsenoside Re showed angiogenesis [41]. |

|

|

| |

| Effects of ginsenoside Rg1 (150–600 nM) on angiogenesis in HUVECs (in vitro). Effects of Rg1 (600 nM/Matrigel) on angiogenesis in Matrigel-implanted mice (in vivo). Ginsenoside Rg1 promoted angiogenesis [42]. |

|

|

| |

| Effects of 20(R)-ginsenoside Rg3(1-1000 nM) on angiogenesis in HUVECs (in vivo). 20(R)-ginsenoside Rg3 showed antiangiogenesis [43]. |

|

|

| |

| Effects of Ginsenoside Rg1 (150 nM) on angiogenesis in HUVECs (in vitro). Ginsenoside Rg1 promoted angiogenesis [44]. |

|

|

| |

| Effects of ginsenoside Rg1 (30 μg/mL) and Re (30 μg/mL) on angiogenesis in HUVECs (in vitro). Effects of Rg1 (50 μg/mL) and Re (50 μg/mL) on angiogenesis in Matrigel-implated mice (in vivo). Ginsenoside Rg1 and Re promoted angiogenesis [45]. |

|

|

| |

| Effects of ginsenoside Rg3 (3 mg/kg, ip) on growth and angiogenesis of ovarian cancer (in vivo). Ginsenoside Rg3 showed antiangiogenesis [46]. |

|

|

| |

| Effects of ginsenoside Rb1 (250 nM) on angiogenesis in HUVECs (in vitro). Ginsenoside Rb1 showed antiangiogenesis [47]. |

|

|

| |

| Effects of ginsenoside Rg1 (500 μg/Matrigel) on angiogenesis in Matrigel-implanted mice (in vivo) Ginsenoside Rg1 promoted angiogenesis [48]. |

|

|

| |

| Effects of saponins (0.1–100 μg/mL) isolated from Panax notoginseng and Rg1(10 μg/mL) on angiogenesis in HUVECs (in vitro). Total saponin and ginsenoside Rg1 promoted angiogenesis [49]. |

|

|

| |

| Effects of ginsenoside Rg3 (20 mg/kg, po) on angiogenesis and growth in lung carcinoma-implanted mice. Ginsenoside Rg3 showed antiangiogenesis [50]. |

|

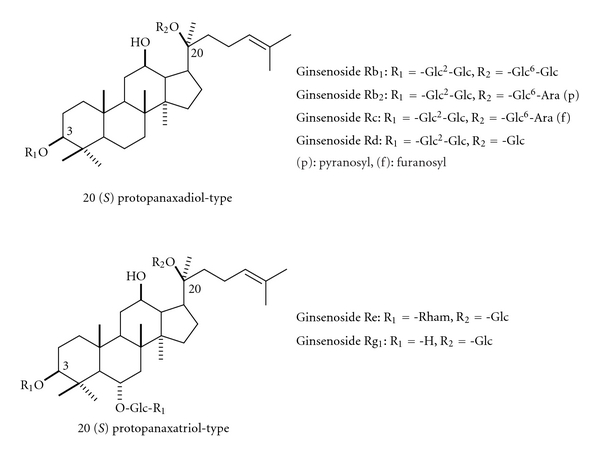

To clarify these differing effects, we first attempted to examine the effects of various ginseng saponins on wound healing. Among six ginseng saponins (ginsenoside Rb1, Rb2, Rc, Rd, Re, and Rg1) (Figure 1), we found that ginsenoside Rb1 enhanced burn-wound healing most strongly.

Figure 1.

The structure of various ginsenosides.

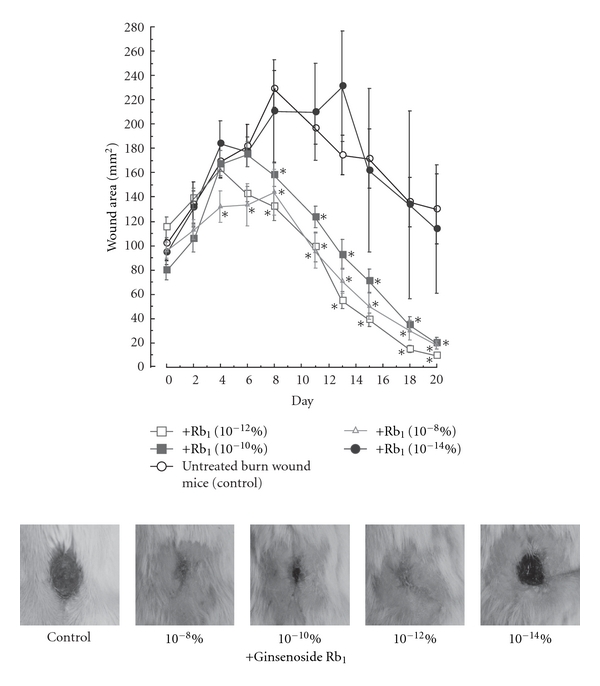

In summary, we reported the promotion of burn-wound healing by the topical application of ginsenoside Rb1 at low doses (100 fg, 10 pg, and 1 ng per wound) to be due to the promotion of angiogenesis during skin wound repair through stimulation of VEGF production and an increase in hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-) 1α expression in keratinocytes and the elevation of interleukin (IL-) 1β from macrophage accumulation in the burn wound area [26]. Furthermore, we found the facilitating effects of ginsenoside Rb1 at low doses (100 fg, 10 pg, and 1 ng per wound) to be due to the promotion of angiogenesis via the activation of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) through an increase in histamine released from mast cells recruited by the stimulation of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) as another mechanism [27]. We will explain our experiments regarding the facilitating effects of ginsenoside Rb1 on burn-wound healing in detail. The burn area in mice treated with a topical application of ginsenoside Rb1 in the range of 10−8% to 10−12% was significantly reduced on days 8–20 compared to that in vehicle-treated burn-wound control mice (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effects of ginsenoside Rb1 on wound healing in mice [26]. After the burn wound was made by applying a customized soldering iron to the skin on the backs of male Balb/c mice (6 weeks old) for 10 s at 250°C, a sterile biopsy punch (8 mm diameter) was used to excise the burnt skin, leaving the underlying fasciae intact. All surgical treatments were performed under anesthesia with pentobarbital. Indicated amounts of ginsenoside Rb1 were applied to the burn wounds surface and then covered with a film dressing for 19 consecutive days. The burn wound site was photographed every other day and burn wound area was measured using a Coordinate Area and Curvimeter Machine (X-PLAN 360 dII). Values are the mean ± SE for 6–12 mice. *Significantly different from vehicle-treated mice, P < 0.05.

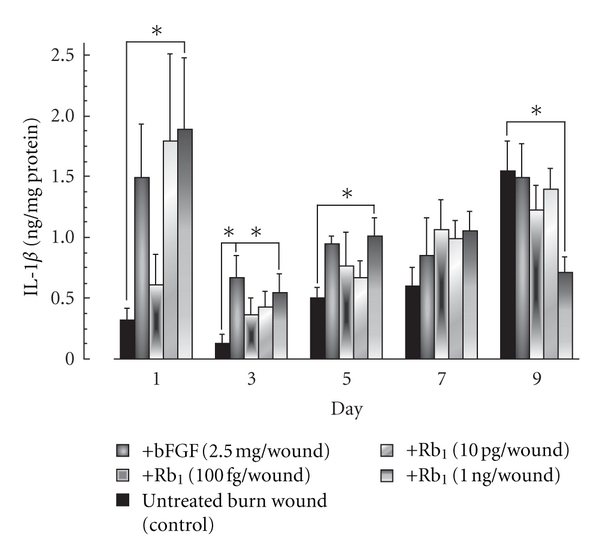

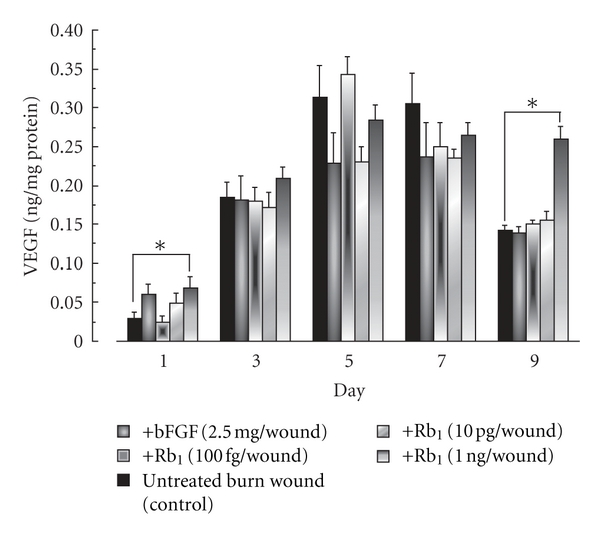

To clarify the mechanism behind the facilitating effect of ginsenoside Rb1 on wound healing, we examined levels of IL-1β and VEGF in exudates of the burn. The levels increased with time over 9 days. At 1 ng of ginsenoside Rb1 per wound, the level of IL-1β was increased on days 1, 3, and 5 but significantly decreased on day 9 compared to that in vehicle-treated control mice (Figure 3). The topical application of bFGF (2.5 μg per wound) also increased IL-1β production on day 3. The VEGF level in the exudates from the wound increased until day 5 and then decreased. The application of ginsenoside Rb1 increased VEGF levels on days 1 and 9 (Figure 4). However, the application of bFGF did not affect VEGF production.

Figure 3.

Effects of ginsenoside Rb1 and bFGF on IL-1β production in the exudates of burns in male Balb/c mice [26]. The burn wounds were created on the backs of male Balb/c mice (6 weeks old) under anesthesia with pentobarbital. A polyethylene filter pellet (about 8 in mm diameter, 3 mm thick) containing the indicated amount of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) or ginsenoside Rb1 was applied to the burn wounds surface. On days 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9, the filter pellets were removed and replaced with fresh filter pellets. For control mice, filter pellets containing saline alone were applied according to the same schedule. Immediately after removal, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.0) (200 μl) was added to each filter pellet and mixed for 10 min. The IL-1β levels in the filter pellets were measured using a mouse IL-1β ELISA kit. Values are the mean ± SE for 6 mice. *Significantly different from control, P < 0.05.

Figure 4.

Effects of ginsenoside Rb1 and bFGF on VEGF production in the exudates of burns in male Balb/c mice [26]. The experiments were performed as described in Figure 3, and the VEGF levels in the filter pellets were measured using a mouse IL-1β ELISA kit. Values are the mean ± SE for 6 mice. *Significantly different from control, P < 0.05.

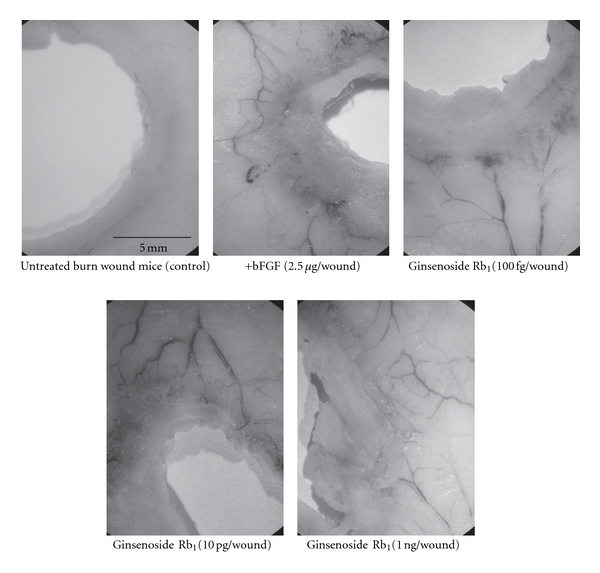

The application of bFGF (2.5 μg per wound) or ginsenoside Rb1 (100 fg, 10 pg, and 1 ng per wound) for 9 days increased the length of blood vessels by 3- to 3.5-fold and the corresponding area by 3.5- to 5.0-fold, compared to the control (Figure 5 and Table 2).

Figure 5.

Photographs showing neovascularization from the tissue surrounding the burn and the effects of the topical application of ginsenoside Rb1 [26]. The experiments were performed as described in Figure 3. On day 9, any angiogenesis in the site surrounding the burn wound was photographed using a stereoscopic microscope.

Table 2.

Effects of ginsenoside Rb1 on angiogenesis from the area surrounding burn wounds in mice [26].

| Treatment | Blood vessel length (mm/field) | Blood vessel area (mm2/field) |

|---|---|---|

| Untreated burn wounds (control) | 75.6 ± 24.9 | 10.5 ± 3.8 |

|

| ||

| +Ginsenoside Rb1 | ||

| (100 fg/wound) | 228.8 ± 38.6* | 46.6 ± 15.0* |

| (10 pg/wound) | 203.0 ± 17.0* | 37.6 ± 5.5* |

| (1 ng/wound) | 274.1 ± 37.4* | 49.9 ± 4.7* |

|

| ||

| +bFGF | 241.5 ± 28.3* | 35.8 ± 5.9* |

The burn wounds were created on the backs of male Balb/c mice (6 weeks old) under anesthesia with pentobarbital. A polyethylene filter pellet (about 8 mm in diameter, 3 mm thick) containing the indicated amount of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) or ginsenoside Rb1 was applied to the burn wound surface. On day 9, any angiogenesis in the site surrounding the burn wound was photographed using a stereoscopic microscope, and the area and length of blood vessels were measured using a Coordinating Area and Curvimeter Machine (X-PLAN 360 dII, Ushitaka, Tokyo, Japan).

Values are the mean ± SE for six mice. *Significantly different from untreated burn wounds (control), P < 0.05.

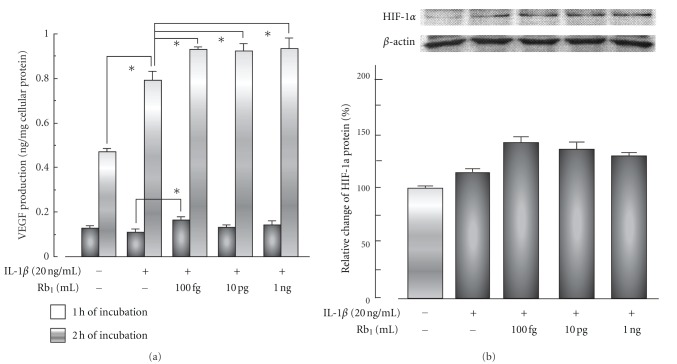

Ginsenoside Rb1 at concentrations from 100 fg/mL to 1 ng/mL enhanced the VEGF production and HIF-1α expression induced by IL-1β in the human keratinocyte cell line HaCaT (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Effects of ginsenoside Rb1 on VEGF production (a) and HIF-1α expression (b) with or without IL-1β in HaCaT cells [26]. The human keratinocyte cell line HaCaT was treated with the indicated amounts of ginsenoside Rb1 in the presence or absence of IL-1β (20 ng/mL) for 1 or 2 h. VEGF levels in the medium were measured using a human VEGF kit. The expression of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-) 1α in the nuclear fraction of HaCaT cells was measured by western blot analysis with mouse anti-HIF-1α and anti-β-actin antibodies. Values are the mean ± SE for six experiments. *Significantly different from control, P < 0.05.

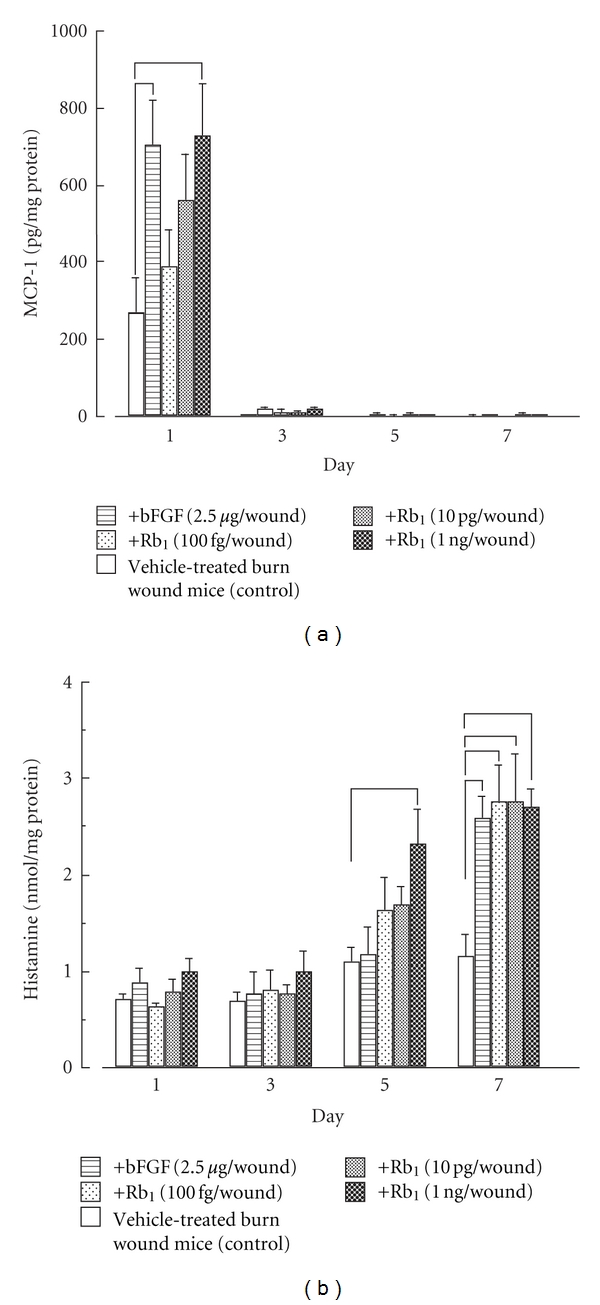

These findings suggest the enhancement of wound healing by ginsenoside Rb1 to be due to the promotion of angiogenesis during the repair process as a result of the stimulation of VEGF production caused by the increase in HIF-1α expression in keratinocytes. Furthermore, the MCP-1 level in the exudates of vehicle-treated (control) mice reached a maximum 1 day after the burn treatment and declined rapidly from day 3. Ginsenoside Rb1 (1 ng per wound) and bFGF (2.5 μg per wound) significantly increased the level of MCP-1 on day 1 compared to that in control mice (Figure 7). Histamine levels in the exudates of the burn wound area increased until day 7. Ginsenoside Rb1 (1 ng per wound) significantly increased the histamine level on day 5 compared to that in control mice (Figure 7). Furthermore, ginsenoside Rb1 (100 fg, 10 pg, and 1 ng per wound) and bFGF (2.5 μg per wound) significantly increased histamine production on day 7 (Figure 7). The facilitating effects of ginsenoside Rb1 may be due to the promotion of angiogenesis via the activation of bFGF through the increase in histamine released from mast cells recruited by the stimulation of MCP-1 production.

Figure 7.

Effects of ginsenoside Rb1 and bFGF on MCP-1 (a) and histamine (b) production in the exudates of burns in male Balb/c mice [27]. The experiments were performed as described in Figure 3, and then MCP-1 and histamine levels in the filter pellets were measured using mouse MCP-1 and histamine ELISA kits, respectively. Values are the mean ± SE for 6 mice. *Significantly different from control, P < 0.05.

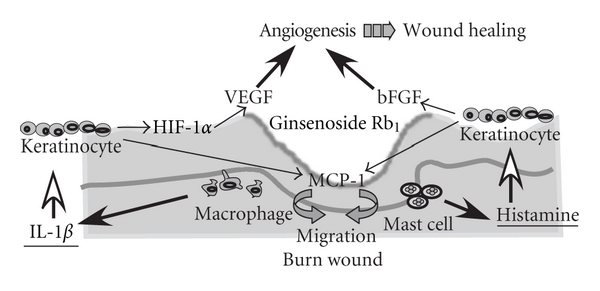

Based on these experimental results, the enhancing effects of ginsenoside Rb1 on burn wound healing are summarized in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

The proposed mechanisms of the enhancing effects of ginsenoside Rb1 on burn wound healing.

It has been reported that ginsenoside Rb2 as well as ginsenoside Rb1 promotes wound healing [24].

3. Effects of Ginsenoside Rb1 on Ultraviolet B (UVB-) Irradiated Skin Damage in Mice

The symptoms of cutaneous aging, such as wrinkles and pigmentation, for example, develop earlier in sun-exposed skin than in unexposed skin, a phenomenon referred to as photoaging. Ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation is one of the most important environmental factors because of its hazardous effects, which include the generation of skin cancer [28], suppression of the immune system [29], and premature skin aging [30].

As shown in Table 3, it has been reported that red ginseng extract prevents skin aging induced by UVB irradiation. However, the active substance(s) has yet to be identified. We found that ginsenoside Rb1 isolated from red ginseng roots inhibited the increases in skin thickness, epidermis, and wrinkle formation induced by chronic UVB irradiation [31]. In this paper, we will introduce the effects of ginsenoside Rb1 on chronic UVB irradiation-induced cutaneous aging in hairless mice.

Table 3.

Effects of Panax ginseng extract on skin aging.

| Effects of the total ginseng saponin fraction (100 to 500 μg/mL) on luciferase reporter gene assays in human dermal fibroblast (in vitro). Effects of the total ginseng saponin fraction (100 to 500 μg/mL) on type I collagen in human dermal fibroblast (in vitro). The total saponin fraction (100 to 500 μg/mL) increased type I procollagen synthesis [51]. |

|

|

| |

| Effects of red ginseng extract (20 and 60 mg/kg, po) on acute UVB-induced skin aging in mice The extract inhibited the increases in epidermis and dermis thickness induced by UVB [52]. |

|

|

| |

| Effects of red ginseng extract (20 mg/kg, ip or topical application of 0.2% cream) on chronic UVB-irradiated skin damage in hairless mice. The extract reduced wrinkling and tumor incidence [53]. |

|

|

| |

| Effects of ginsenoside Rb1 (100 fg, 10 pg, or 1 ng/mouse, topical application) on chronic UVB-irradiated skin aging in hairless mice. Ginsenoside Rb1 inhibited the increase in skin thickness, wrinkling, and epidermis in UVB-irradiated hairless mice [31]. |

|

|

| |

| Effects of red ginseng extract (a diet containing 0.5 and 2.5% red ginseng extract) on UVB-irradiated skin aging in hairless mice. The extract reduced wrinkling, the mRNA level of procollagen type I, and the MMP-1 level [54]. |

|

|

| |

| Healthy female volunteers over 40 years of age were randomized in a double-blind fashion to receive either red ginseng extract (3 g/day) or placebo for 24 weeks. (Clinical study). Red ginseng extract caused an improvement in facial wrinkling and increase in type I procollagen synthesis [55]. |

|

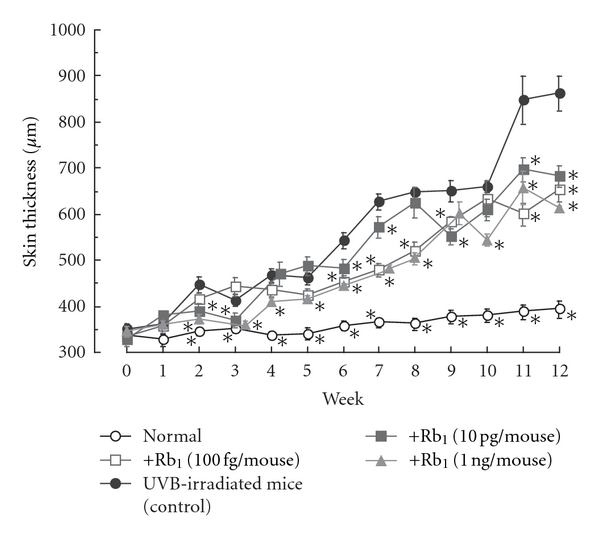

The topical application of ginsenoside Rb1 at lower doses, 100 fg, 10 pg, and 1 ng/mouse, significantly inhibited the increase in skin thickness induced by UVB irradiation during weeks 2 to 12 compared to the skin thickness of vehicle-treated UVB-irradiated mice (control) (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Effects of ginsenoside Rb1 on skin thickness in chronic UVB-irradiated male hairless (HRM-1) mice [31]. The initial dose of UVB was set at 36 mJ/cm2, which was subsequently increased to 54 mJ/cm2 at weeks 1–4, 72 mJ/cm2 at weeks 4–7, 108 mJ/cm2 at weeks 7–10, and finally 122 mJ/cm2 at weeks 10–12 in male albino hairless HOS: HR-1 mice. The frequency of UVB irradiation was set at three times per week. Ginsenoside Rb1 (100 fg, 10 pg, and 1 ng/mouse) was applied topically to the dorsal region of each mouse every day for 12 weeks. The dorsal skin of the hairless mice was lifted up by pinching gently under anesthetization with pentobarbital, and skin-fold thickness was measured using a Quick Mini caliper. Skin thickness after UVB irradiation was measured every week. Values are the mean ± SE for 6 mice. *Significantly different from vehicle-treated mice, P < 0.05.

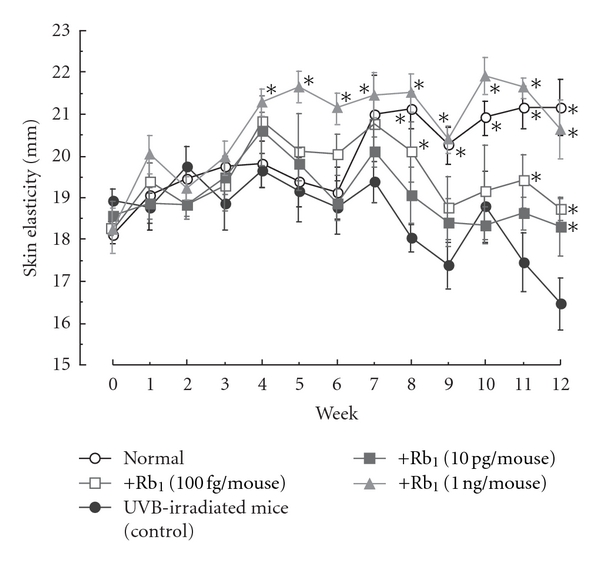

The reduction in skin elasticity induced by UVB irradiation was significantly inhibited by the topical application of ginsenoside Rb1 (100 fg, 10 pg, and 1 ng/mouse) during weeks 6 to 12 compared to that of control mice (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Effects of ginsenoside Rb1 on skin elasticity in chronic UVB-irradiated male hairless (HRM-1) mice [31]. The experiments were performed as described in Figure 9. The dorsal skin was lifted up and skin stretch was measured using a digimatic caliper. Skin elasticity after UVB irradiation was measured every week. Values are the mean ± SE for 6 mice. *Significantly different from vehicle-treated mice, P < 0.05.

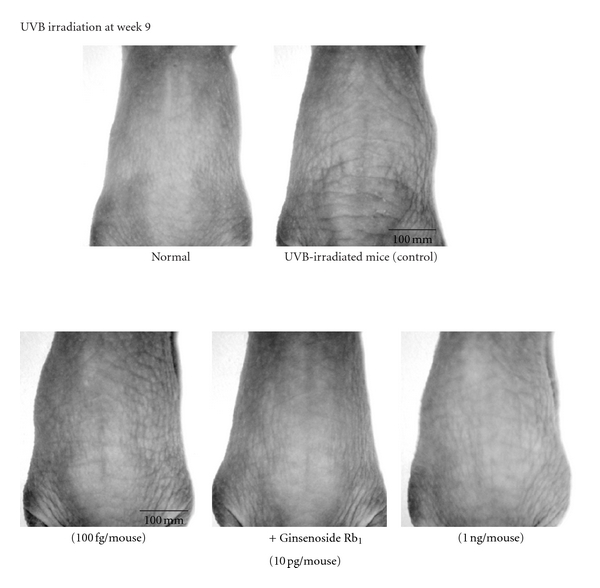

Wrinkling induced by UVB irradiation at week 9 was inhibited by the topical application of ginsenoside Rb1 (100 fg, 10 pg, and 1 ng/mouse) (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Photograph showing skin wrinkling induced by chronic UVB irradiation and the effects of topically applied ginsenoside Rb1 [31]. The experiments were performed as described in Figure 9. To evaluate the formation of wrinkles after the UVB irradiation, the UVB-irradiated dorsal area (site of wrinkles) of each hairless mouse was photographed at 9 weeks.

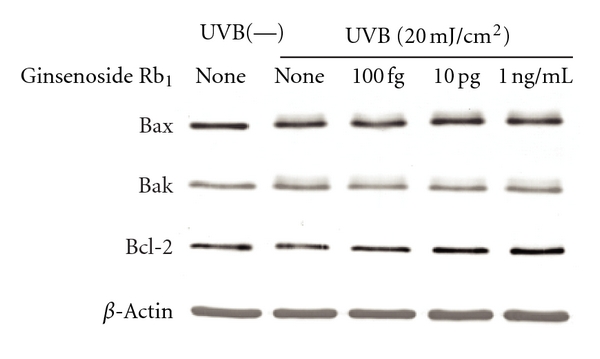

The topical application of ginsenoside Rb1 (100 fg, 10 pg, and 1 ng/mouse) inhibited the increase in epidermal thickness induced by UVB irradiation but had no effect on the increase in the extracellular matrix of the dermis (Table 4). The occurrence of apoptotic cells was localized to the stratum granulosum of the epidermis and was increased by UVB irradiation. The increase in apoptotic cell levels induced UVB irradiation was significantly inhibited by ginsenoside Rb1 (100 fg. 10 pg, and 1 ng/mouse). Furthermore, 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG, a marker of oxidative DNA damage) [32] was also localized to the stratum basale and dermis, and its level was increased by UVB irradiation. The increase in 8-OHdG-positive cells induced by UVB irradiation was inhibited by ginsenoside Rb1 (Table 5). UVB (20 mJ/cm2) irradiation reduced the level of Bcl-2 expression in human primary keratinocytes. Conversely, UVB irradiation had no effect on Bak or Bax expression. Ginsenoside Rb1 increased the Bcl-2 levels in UVB-treated human primary keratinocytes at the lower concentrations of 100 fg, 10 pg, and 1 ng/mL (Figure 12).

Table 4.

Effects of ginsenoside Rb1 on the thickness of the epidermis and extracellular matrix (ECM) of the dermis at week 12 in UVB-irradiated hairless mice [31].

| Epidermis (μm) | ECM (μm) in dermis | |

|---|---|---|

| Normal mice | 14.74 ± 1.11* | 332.51 ± 23.18* |

| Vehicle-treated UVB-irradiated mice (control) | 142.59 ± 25.37 | 632.32 ± 31.96 |

|

| ||

| +Ginsenoside Rb1 | ||

| (100 fg/mouse) | 46.00 ± 6.26* | 561.86 ± 45.22 |

| (10 pg/mouse) | 49.24 ± 4.73* | 560.67 ± 44.81 |

| (1 ng/mouse) | 39.84 ± 6.26* | 585.63 ± 31.35 |

The initial dose of UVB was set at 36 mJ/cm2, which was subsequently increased to 54 mJ/cm2 at weeks 1–4, 72 mJ/cm2 at weeks 4–7, 108 mJ/cm2 at weeks 7–10, and finally to 122 mJ/cm2 at weeks 10–12 in male albino hairless HOS: HR-1 mice. The frequency of UVB irradiation was set at three times per week. Ginsenoside Rb1 (100 fg, 10 pg, and 1 ng/mouse) was applied topically to the dorsal region of each mouse every day for 12 weeks. The dorsal skin samples (about 3 cm2) removed at week 12 were fixed in 10% buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 μm thickness, deparaffinized, and stained with hematoxylin-eosin (HE) and Azan. Four different microscopic fields (×200 magnification) per plate were photographed. The thickness of the epidermis and dermis thickness were measured from the samples stained by HE and Azan, using a Digimatic Caliper.

Values are the mean ± SE for 6 mice. *Significantly different from UVB-irradiated hairless mice (control), P < 0.05.

Table 5.

Effects of ginsenoside Rb1 on the numbers of apoptotic and 8-OHdG-positive cells at week 12 in the skin of UVB-irradiated hairless mice [31].

| Apoptotic cells (number/field) | 8-OHdG-positive cells (number/field) | |

|---|---|---|

| Normal mice | 0 ± 0* | 106 ± 7* |

|

| ||

| Vehicle-treated UVB-irradiated mice (control) | 102 ± 10 | 286 ± 32 |

|

| ||

| +Ginsenoside Rb1 | ||

| (100 fg/mouse) | 19 ± 11* | 150 ± 24* |

| (10 pg/mouse) | 11 ± 11* | 183 ± 27* |

| (1 ng/mouse) | 9 ± 9* | 109 ± 26* |

Ginsenoside Rb1 (100 fg, 10 pg, and 1 ng/mouse) was applied topically to the dorsal region of each mouse every day for 12 weeks. The expression levels of apoptotic cells and 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) (marker of oxidative DNA damage) in the dorsal skin of UVB-irradiated hairless mice were examined by the TUNEL method using an apoptosis in situ detection kit and an immunoperoxidase technique using anti-8-OHdG antibody.

Values are the mean ± SE for 6 mice. *Significantly different from UVB-irradiated mice (control), P < 0.05.

Figure 12.

Effects of ginsenoside Rb1 on Bax, Bak, and Bcl-2 expression levels in UVB-irradiated human primary keratinocytes [31]. Human keratinocytes (3 × 105 cells) were seeded in a 100-mm culture dish and cultured in KG-2 medium for 48 h. The cells were irradiated with UVB (20 mJ/cm2) and treated with the indicated amounts of ginsenoside Rb1 for 24 h in KB-2 medium. After being washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.0), the cells were treated with lysed buffer. The supernatant obtained by centrifugation was subjected to a western blot analysis with anti-Bcl-2, anti-Bax, anti-Bak, and anti-β-actin antibodies.

UVB exposure of skin cells results in several types of DNA damage such as the formation of the cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer, pyrimidine pyrimidone photodimers and 8-OHdG [33–35], and consequently DNA damage induced by long-term UV exposure leads to skin carcinogenesis. Furthermore, there are many reports that apoptotic stimuli such as UV radiation and tumor necrosis factor-α induce cell death by activating caspases [36]. Bcl-2 is a member of the large Bcl-2 family and protects cells from apoptosis. On the other hand, it has been reported that Bax and Bak appear to permeabilize the outer mitochondrial membrane, allowing the efflux of apoptogenic proteins [37–39]. The protective effect of ginsenoside Rb1 on UVB-mediated apoptosis may be partly due to the upregulation of Bcl-2 expression in human keratinocytes. Thus, the protective effect of ginsenoside Rb1 on skin photoaging induced by chronic UVB exposure may be due to the increase in collagen synthesis and/or the inhibition of metalloproteinases expression in dermal fibroblast and the inhibition of epidermal hyperplasia. Further research is needed to clarify the mechanism of the protective effect of ginsenoside Rb1 on photoaging induced by chronic UVB irradiation of the skin.

4. Conclusion

The topical application of ginsenoside Rb1 isolated from red ginseng roots enhances burn wound healing, and ginsenoside Rb1 prevents chronic UVB-induced skin photoaging, at very low doses. Further studies will be needed to clarify the clinical significance of these findings for skin damage induced by burn wounds or UV irradiation.

Acknowledgments

The authors' paper in this review was partly supported by grants from the Conference of red ginseng and a Grant-in-aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture Sports, Science and Technology of Japan. They thank Dr. K. Samaukawa, Dr. H. Fujita, and Dr. K. Ikoma for their encouragement and suggestions throughout the development of this work.

References

- 1.O’Riordain MG, Collins KH, Pilz M, Saporoschetz IB, Mannick JA, Rodrick ML. Modulation of macrophage hyperactivity improves survival in a burn-sepsis model. Archives of Surgery. 1992;127(2):152–158. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1992.01420020034005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kataranovski M, Magič Z, Pejnovič N. Early inflammatory cytokine and acute phase protein response under the stress of thermal injury in rats. Physiological Research. 1999;48(6):473–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altavilla D, Saitta A, Cucinotta D, et al. Inhibition of lipid peroxidation restores impaired vascular endothelial growth factor expression and stimulates wound healing and angiogenesis in the genetically diabetic mouse. Diabetes. 2001;50(3):667–674. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.3.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown LF, Yeo KT, Berse B, et al. Expression of vascular permeability factor (vascular endothelial growth factor) by epidermal keratinocytes during wound healing. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1992;176(5):1375–1379. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.5.1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin P. Wound healing—aiming for perfect skin regeneration. Science. 1997;276(5309):75–81. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sen CK, Khanna S, Babior BM, Hunt TK, Christopher Ellison E, Roy S. Oxidant-induced vascular endothelial growth factor expression in human keratinocytes and cutaneous wound healing. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(36):33284–33290. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203391200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nissen NN, Polverini PJ, Koch AE, Volin MV, Gamelli RL, DiPietro LA. Vascular endothelial growth factor mediates angiogenic activity during the proliferative phase of wound healing. American Journal of Pathology. 1998;152(6):1445–1452. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galiano RD, Tepper OM, Pelo CR, et al. Topical vascular endothelial growth factor accelerates diabetic wound healing through increased angiogenesis and by mobilizing and recruiting bone marrow-derived cells. American Journal of Pathology. 2004;164(6):1935–1947. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63754-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DiPietro LA, Polverini PJ, Rahbe SM, Kovacs EJ. Modulation of JE/MCP-1 expression in dermal wound repair. American Journal of Pathology. 1995;146(4):868–875. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiPietro LA, Burdick M, Low QE, Kunkel SL, Strieter RM. Mip-1α as a critical macrophage chemoattractant in murine wound repair. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1998;101(8):1693–1698. doi: 10.1172/JCI1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DiPietro LA, Reintjes MG, Low QEH, Levi B, Gamelli RL. Modulation of macrophage recruitment into wounds by monocyte chemoattractant protein-1. Wound Repair and Regeneration. 2001;9(1):28–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.2001.00028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heinrich SA, Messingham KAN, Gregory MS, et al. Elevated monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 levels following thermal injury precede monocyte recruitment to the wound site and are controlled, in part, by tumor necrosis factor-α. Wound Repair and Regeneration. 2003;11(2):110–119. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.2003.11206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ristimäki A, Narko K, Enholm B, Joukov V, Alitalo K. Proinflammatory cytokines regulate expression of the lymphatic endothelial mitogen vascular endothelial growth factor-C. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(14):8413–8418. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.14.8413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frank S, Stallmeyer B, Kämpfer H, Kolb N, Pfeilschifter J. Nitric oxide triggers enhanced induction of vascular endothelial growth factor expression in cultured keratinocytes (HaCaT) and during cutaneous wound repair. FASEB Journal. 1999;13(14):2002–2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ben-Av P, Crofford LJ, Wilder RL, Hla T. Induction of vascular endothelial growth factor expression in synovial fibroblasts by prostaglandin E and interleukin-1: a potential mechanism for inflammatory angiogenesis. FEBS Letters. 1995;372(1):83–87. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00956-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Konishi N, Miki C, Yoshida T, Tanaka K, Toiyama Y, Kusunoki M. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist inhibits the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in colorectal carcinoma. Oncology. 2005;68(2-3):138–145. doi: 10.1159/000086768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gavrilin MA, Deucher MF, Boeckman F, Kolattukudy PE. Monocyte chemotactic protein 1 upregulates IL-1β expression in human monocytes. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2000;277(1):37–42. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trautmann A, Toksoy A, Engelhardt E, Bröcker EB, Gillitzer R. Mast cell involvement in normal human skin wound healing: expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein-I is correlated with recruitment of mast cells which synthesize interleukin-4 in vivo. Journal of Pathology. 2000;190(1):100–106. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(200001)190:1<100::AID-PATH496>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weller K, Foitzik K, Paus R, Syska W, Maurer M. Mast cells are required for normal healing of skin wounds in mice. FASEB Journal. 2006;20(13):E1628–E1635. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-5837fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Numata Y, Terui T, Okuyama R, et al. The accelerating effect of histamine on the cutaneous wound-healing process through the action of basic fibroblast growth factor. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2006;126(6):1403–1409. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanzaki T, Morisaki N, Shiina R, Saito Y. Role of transforming growth factor-β pathway in the mechanism of wound healing by saponin from Ginseng Radix rubra. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1998;125(2):255–262. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morisaki N, Watanabe S, Tezuka M, et al. Mechanism of angiogenic effects of saponin from Ginseng Radix rubra in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1995;115(7):1188–1193. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15023.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sengupta S, Toh SA, Sellers LA, et al. Modulating angiogenesis: the yin and the yang in ginseng. Circulation. 2004;110(10):1219–1225. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140676.88412.CF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi S. Epidermis proliferative effect of the Panax ginseng ginsenoside Rb2. Archives of Pharmacal Research. 2002;25(1):71–76. doi: 10.1007/BF02975265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sato K, Mochizuki M, Saiki I, Yoo YC, Samukawa KI, Azuma I. Inhibition of tumor angiogenesis and metastasis by a saponin of Panax ginseng, ginsenoside-Rb2. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 1994;17(5):635–639. doi: 10.1248/bpb.17.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kimura Y, Sumiyoshi M, Kawahira K, Sakanaka M. Effects of ginseng saponins isolated from Red Ginseng roots on burn wound healing in mice. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2006;148(6):860–870. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawahira K, Sumiyoshi M, Sakanaka M, Kimura Y. Effects of ginsenoside Rb1 at low doses on histamine, substance P, and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 in the burn wound areas during the process of acute burn wound repair. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2008;117(2):278–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Gruijl FR, Sterenborg HJCM, Forbes PD, et al. Wavelength dependence of skin cancer induction by ultraviolet irradiation of albino hairless mice. Cancer Research. 1993;53(1):53–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beissert S, Schwarz T. Mechanisms involved in ultraviolet light-induced immunosuppression. Journal of Investigative Dermatology Symposium Proceedings. 1999;4(1):61–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.jidsp.5640183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fisher GJ, Wang Z, Datta SC, Varani J, Kang S, Voorhees JJ. Pathophysiology of premature skin aging induced by ultraviolet light. New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;337(20):1419–1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711133372003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim YG, Sumiyoshi M, Sakanaka M, Kimura Y. Effects of ginseng saponins isolated from red ginseng on ultraviolet B-induced skin aging in hairless mice. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2009;602(1):148–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toyokuni S, Tanaka T, Hattori Y, et al. Quantitative immunohistochemical determination of 8-hydroxy-2’- deoxyguanosine by a monoclonal antibody N45.1: its application to ferric nitrilotriacetate-induced renal carcinogenesis model. Laboratory Investigation. 1997;76(3):365–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Budiyanto A, Ahmed NU, Wu A, et al. Protective effect of topically applied olive oil against photocarcinogenesis following UVB exposure of mice. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21(11):2085–2090. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.11.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katiyar SK, Matsui MS, Mukhtar H. Kinetics of UV light-induced cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers in human skin in vivo: an immunohistochemical analysis of both epidermis and dermis. Photochemistry and Photobiology. 2000;72(6):788–793. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2000)072<0788:koulic>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cadet J, Sage E, Douki T. Ultraviolet radiation-mediated damage to cellular DNA. Mutation Research. 2005;571(1-2):3–17. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cryns V, Yuan J. Proteases to die for. Genes and Development. 1998;12(11):1551–1570. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.11.1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Green DR, Reed JC. Mitochondria and apoptosis. Science. 1998;281(5381):1309–1312. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martinou JC, Green DR. Breaking the mitochondrial barrier. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2001;2(1):63–67. doi: 10.1038/35048069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Newmeyer DD, Ferguson-Miller S. Mitochondria: releasing power for life and unleashing the machineries of death. Cell. 2003;112(4):481–490. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mochizuki M, Yoo YC, Matsuzawa K, et al. Inhibitory effect of tumor metastasis in mice by saponins, ginsenoside- Rb2, 20(R)- and 20(S)-ginsenoside-Rg3, of Red ginseng. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 1995;18(9):1197–1202. doi: 10.1248/bpb.18.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang YC, Chen CT, Chen SC, et al. A natural compound (Ginsenoside Re) isolated from Panax ginseng as a novel angiogenic agent for tissue regeneration. Pharmaceutical Research. 2005;22(4):636–646. doi: 10.1007/s11095-005-2500-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yue PYK, Wong DYL, Ha WY, et al. Elucidation of the mechanisms underlying the angiogenic effects of ginsenoside Rg1in vivo and in vitro. Angiogenesis. 2005;8(3):205–216. doi: 10.1007/s10456-005-9000-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yue PYK, Wong DYL, Wu PK, et al. The angiosuppressive effects of 20(R)- ginsenoside Rg3. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2006;72(4):437–445. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leung KW, Pon YL, Wong RNS, Wong AST. Ginsenoside-Rg1 induces vascular endothelial growth factor expression through the glucocorticoid receptor-related phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt and β-catenin/T-cell factor-dependent pathway in human endothelial cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281(47):36280–36288. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606698200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu LC, Chen SC, Chang WC, et al. Stability of angiogenic agents, ginsenoside Rg1 and Re, isolated from Panax ginseng: in vitro and in vivo studies. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2007;328(2):168–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu TM, Xin Y, Cui MH, Jiang X, Gu LP. Inhibitory effect of ginsenoside Rg3 combined with cyclophosphamide on growth and angiogenesis ovarian cancer. Chinese Medical Journal. 2007;120(7):584–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leung KW, Cheung LWT, Pon YL, et al. Ginsenoside Rb1 inhibits tube-like structure formation of endothelial cells by regulating pigment epithelium-derived factor through the oestrogen β receptor. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2007;152(2):207–215. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin KMC, Hsu CH, Rajasekaran S. Angiogenic evaluation of ginsenoside Rg1 from Panax ginseng in fluorescent transgenic mice. Vascular Pharmacology. 2008;49(1):37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hong SJ, Wan JB, Zhang Y, et al. Angiogenic effect of saponin extract from Panax notoginseng on HUVECs in vitro and zebrafish in vivo. Phytotherapy Research. 2009;23(5):677–686. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu TG, Huang Y, Cui DD, et al. Inhibitory effect of ginsenoside Rg3 combined with gemcitabine on angiogenesis and growth of lung cancer in mice. BMC Cancer. 2009;9, article 250 doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee J, Jung E, Lee J, et al. Panax ginseng induces human type I collagen synthesis through activation of Smad signaling. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2007;109(1):29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim YG, Sumiyoshi M, Kawahira K, Sakanaka M, Kimura Y. Effects of red ginseng extract on ultraviolet B-irradiated skin change in C57BL mice. Phytotherapy Research. 2008;22(11):1423–1427. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee HJ, Kim JS, Song MS, et al. Photoprotective effect of red ginseng against ultraviolet radiation-induced chronic skin damage in the hairless mouse. Phytotherapy Research. 2009;23(3):399–403. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kang TH, Park HM, Kim YB, et al. Effects of red ginseng extract on UVB irradiation-induced skin aging in hairless mice. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2009;123(3):446–451. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cho S, Won CH, Lee DH, et al. Red ginseng root extract mixed with torilus fructus and corni fructus improves facial wrinkles and increases type I procollagen synthesis in human skin: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Journal of Medicinal Food. 2009;12(6):1252–1259. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2008.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]