Abstract

Traditional knowledge is an important source of obtaining new phytotherapeutic agents. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants was conducted in Nossa Senhora Aparecida do Chumbo District (NSACD), located in Poconé, Mato Grosso, Brazil using semi-structured questionnaires and interviews. 376 species of medicinal plants belonging to 285 genera and 102 families were cited. Fabaceae (10.2%), Asteraceae (7.82%) and Lamaceae (4.89%) families are of greater importance. Species with the greater relative importance were Himatanthus obovatus (1.87), Hibiscus sabdariffa (1.87), Solidago microglossa (1.80), Strychnos pseudoquina (1.73) and Dorstenia brasiliensis, Scoparia dulcis L., and Luehea divaricata (1.50). The informant consensus factor (ICF) ranged from 0.13 to 0.78 encompassing 18 disease categories,of which 15 had ICF greater than 0.50, with a predominance of disease categories related to injuries, poisoning and certain other consequences of external causes (ICF = 0.78) having 65 species cited while 20 species were cited for mental and behavioral disorders (ICF = 0.77). The results show that knowledge about medicinal plants is evenly distributed among the population of NSACD. This population possesses medicinal plants for most disease categories, with the highest concordance for prenatal, mental/behavioral and respiratory problems.

1. Introduction

Despite the fact that modern medicine, on the basis of the complex pharmaceutical industry, is well developed in most part of the world, the World Health Organization (WHO) through it Traditional Medicine Program recommends its Member States to formulate and develop policies for the use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in their national health care programmes [1]. Among the components of CAM, phytotherapy practiced by the greater percentage of the world population through the use of plants or their derivatives, occupies a significant and unique position [2].

In this sense, documentation of the indigenous knowledge through ethnobotanical studies is important in the conservation and utilization of biological resources [3].

Brazil is a country with floral megadiversity, possessing six ecological domains, namely, Amazonian forest, Caatinga, Pampas, Cerrado, Atlantic Forest, and the Pantanal [4]. Mato Grosso region is noteworthy in this regard, as it occupies a prominent position both in the national and international settings, for it presents three major Brazilian ecosystems (the Pantanal, Cerrado, and Amazonian rainforest). Besides this, it also hosts diverse traditional communities in its territories, namely, the Indians descents (Amerindians), African descents, and the white Europeans. However, due to the mass migration from the rural areas and technological development, coupled with globalization of knowledge by the dominant nations, cultural tradition concerning the use of medicinal plants is in the major phase of declining [5].

The Pantanal is distinguishably the largest wetland ecosystem of the world, according to the classification by UNESCO World Heritage Center (Biosphere Reserve) [4]. The Pantanal vegetation is a mosaic consisting of species of the Amazonian rainforest, Cerrado, Atlantic forest, and Bolivian Chaco, adapted to special conditions, where there is alternations of both high humidity and pronounced dryness during the time of the year [4]. The presence in the Pantanal of the traditional populations that use medicinal plants for basic health care makes this region an important field for the ethnobotanical and ethnopharmacological studies [6, 7].

Because of the fact that the Pantanal communities are relatively isolated, they have developed private lives that involved much reliance on profound knowledge of the biological cycles, utilization of natural resources, and traditional technology heritage [8].

As a result of the aforementioned, this study aimed to systematically and quantitatively evaluate the information gathered from these Pantanal communities, highlight the relevance of the ethnobotanical findings, and cite and discuss relevant literatures related to medicinal plants with greater relative importance (RI) and high informant consensus factor (ICF) values obtained in the study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

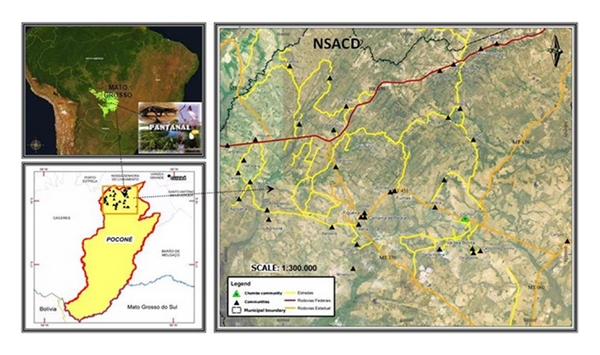

For the choice of study area, literature search was conducted to identify the Pantanal region in Mato Grosso, consisting of traditional communities where such studies have not yet been conducted and/or there were no ethnobotanical survey publications. The study design was cross-sectional and was conducted between the period of November, 2009 and February, 2010. The study setting chosen was NSACD located in the Poconé municipality, Mato Grosso State, Central West of Brazil (Figure 1) with coordinates of 16° 02′ 90′′ S and 056° 43′ 49′′ W. Poconé is located within the region of Cuiabá River valley, with an altitude of 142 m, occupies a territorial area of 17,260.86 km2, and of tropical climate. The mean annual temperature is 24°C (4–42°C) and the mean annual rainfall is 1,500 mm with rainy season occurring between December and February. The municipality is composed of 2 Districts (NSAC and Cangas), 5 villages, 11 settlements, 14 streets, and 72 communities (countryside) [9]. The population of NSACD is estimated to be 3,652 inhabitants, representing 11.5% of Poconé municipality [10]. The principal economic activities are mainly livestock farming, mining, and agriculture with great tourism potentials, because Poconé municipality is the gateway to the Pantanal region [9].

Figure 1.

Location of the study area. Poconé, Mato Grosso, in Midwest of Brazil.

2.2. Consent and Ethical Approval

Authorization and ethical clearance were sought from the relevant government (Health authority of Poconé and the National Council of Genetic Heritage of the Ministry of Environment (CGEN/MMA), Resolution 247 published in the Federal Official Gazette, in October, 2009, on access to the traditional knowledge for scientific research and Federal University of Mato Grosso and Júlio Muller Hospital Research Ethical Committees, Protocol 561/CEP-HUJM/08 authorities. Previsits were made to each community of NSACD to present the research project as well as to seek the consent of each potential informant.

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

In this present study, sampling was done using probabilistic simple randomization and stratified sampling techniques [10, 11].

The population studied consists of inhabitants of 13 communities of NSACD, Mato Grosso State, considering an informant per family. The criteria for each informant chosen were age of 40 and above, residing in NSACD for more than 5 years (because there is large migration into the area because of the presence of ethanol producing factory).

These criteria are in line with the study objective coupled with the information gathered from the local authority [12].

In order to determine the estimated sample size (n), in this case, the number of families to be sampled per communities being considered, the following formula was utilized [11, 13]:

| (1) |

This study considered the population size of 1,179 families (N = 1, 179), confidence coefficient of 95% (z/2 = 1.96), sampling error of 0.05 (d = 0.05), a proportion of 0.5 (P = 0.5). It should be noted that the P = 0.5 was assigned due to nonexistence of previous information about this value as is usual in practice, to obtain conservative sample size which is representative at the same time.

In determining the sample size for the microarea, 5% error and 10% loss in sample were considered. To determine the sample size in each microarea, the sample size (290) was multiplied by the sampling fraction of each microarea and dividing the total number of families of the same microarea with the total number of families of all the microareas (1,179), thereby arriving at the sample sizes for each area as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Distribution of the 13 communities of Nossa Senhora Aparecida do Chumbo District.

| ID | COMMUNITY | Total number of individuals | Total number of families | Sample fraction | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chumbo | 946 | 216 | 0.1832 | 52 |

| 2 | Canto do Agostinho, Santa Helena, Os Cagados, Várzea bonita | 179 | 52 | 0.0441 | 15 |

| 3 | Furnas II, Salobra, Zé Alves | 165 | 59 | 0.0500 | 15 |

| 4 | Campina II, Furnas I, Mundo Novo, Rodeio | 279 | 81 | 0.0687 | 20 |

| 5 | Campina de Pedra, Imbé | 188 | 67 | 0.0568 | 16 |

| 6 | Barreirinho, Coetinho, Figueira | 253 | 95 | 0.0806 | 23 |

| 7 | Bahia de Campo | 257 | 74 | 0.0628 | 18 |

| 8 | Agrovila, São Benedito | 184 | 66 | 0.0560 | 16 |

| 9 | Agroana | 372 | 178 | 0. 1510 | 44 |

| 10 | Bandeira, Minadouro | 248 | 82 | 0.0696 | 20 |

| 11 | Carretão, Deus Ajuda, Sangradouro, Pesqueiro, Varzearia | 216 | 77 | 0.0653 | 19 |

| 12 | Chafariz, Ramos, Sete Porcos, Urubamba | 208 | 67 | 0.0568 | 16 |

| 13 | Céu Azul, Capão Verde, Morro Cortado, Passagem de Carro, Varal | 157 | 65 | 0.0551 | 16 |

|

| |||||

| Total | 3,652 | 1,179 | 1.0000 | 290 | |

ID = identification of the microarea.

The interviews were conducted with the help of 12 trained applicators, under the supervision of the respective investigator. Data collected included sociodemographic details, vernacular names of the plant species with their medicinal uses, methods of drug preparation, and other relevant information. The ethnobotanical data were organized using the Microsoft Office Access 2003 program and statistically analyzed using SPSS, version 15 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA).

2.4. Plant Collection, Identification, and Herborization

The collection of plant materials were done in collaboration with the local specialists, soon after the interviews. Both indigenous and scientific plant names were compiled. The plant materials collected during the study period were herborized, mounted as herbarium voucher specimens, and deposited for taxonomic identification and inclusion in the collection of Federal University of Mato Grosso and CGMS Herbarium of Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil.

Plant species were identified according to standard taxonomic methods, based on floral morphological characters, analytical keys, and using, where possible, samples for comparison, as well as consultations with experts and literature [6, 7, 14–19]. The plant species obtained were grouped into families according to the classification system of Cronquist [20], with the exception of the Pteridophyta and Gymnospermae. For corrections of scientific names and families, the official website of the Missouri Botanical Garden was consulted [21].

2.5. Quantitative Ethnobotany

The relative importance (RI) of each plant species cited by the informants was calculated according to a previously proposed method [22]. In order to calculate RI, the maximum obtainable by a species is two was calculated using (2) according to Oliveira et al. [23]

| (2) |

where RI: relative importance; NCS: number of body systems. It is given by the number of body systems, treated by a species (NSCS) over the total number of body system treated by the most versatile species (NSCSV): NCS = NSCS/NSCSV; NP: number of properties attributed to a specific species (NPS) over the total number of properties attributed to the most versatile species (NPSV): NP = NPS/NPSV.

We sought to identify the therapeutic indications which were more important in the interviews to determine the informant consensus factor (ICF), which indicates the homogenity of the information [23].

The ICF will be low (close to 0), if the plants are chosen randomly, or if the informants do not exchange information about their uses. The value will be high (close to 1), if there is a well defined criterion of selection in the community and/or if the information is exchanged among the informants [23].

ICF was calculated using the number of use citations in each category of plant disease (n ur), minus the number of species used (n t) divided by the number of use citations in each category minus one on the basis of (3):

| (3) |

The citations for therapeutic purposes were classified using the 20 categories of the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th edition-CID [24]: injuries, certain infectious, and parasitic diseases (I); neoplasms-tumors (II), diseases of blood and blood-forming organs and certain disorders involving the immune mechanism (III), endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases (IV) mental and behavioral disorders (V), nervous system (VI), diseases of eye and adnexa (VII), diseases of the ear and mastoid process (VIII), diseases of the circulatory system (IX), respiratory diseases (X), digestive diseases (XI), diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue (XII), diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue (XIII), genitourinary diseases (XIV), pregnancy, childbirth and (XV), certain conditions originating during the perinatal period (XVI), symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings, not elsewhere classified (XVIII) and injury, poisoning and certain other consequences of external causes (XIX).

We selected for further discussion species that presented RI ≥ 1.5, and are in a category with high ICF. We conducted literature review using among others, the databases of Web of Science, MEDLINE, SciELO and including nonindexed works. We also searched national data bases for dissertations and theses.

3. Results

A total of 262 informants were interviewed, representing 7.17% of the population of NSACD, 22.22% of the population aged ≥40 years and residing in the District for over five years. Of the respondents, 69% were female and 31% male, aged 40–94 years (median 55). 68% were born in the city of Poconé, and 62% have been residents for over 20 years in the District (Table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution of the 13 communities of Nossa Senhora Aparecida do Chumbo District, Poconé, Mato Grosso, Brazil.

| ID | Comunity | Population | Number of individualsa | Sample fraction | Sample size | N | Plant citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chumbo | 946 | 216 | 0.1832 | 52 | 50 | 827 |

| 2 | Canto do Agostinho, Santa Helena, Os Cagados, Várzea bonita | 179 | 52 | 0.0441 | 15 | 10 | 131 |

| 3 | Furnas II, Salobra, Zé Alves | 165 | 59 | 0.050 | 15 | 10 | 99 |

| 4 | Campina II, Furnas I, Mundo Novo, Rodeio | 279 | 81 | 0.0687 | 20 | 11 | 179 |

| 5 | Campina de Pedra, Imbé | 188 | 67 | 0.0568 | 16 | 12 | 173 |

| 6 | Barreirinho, Coetinho, Figueira | 253 | 95 | 0.0806 | 23 | 23 | 213 |

| 7 | Bahia de Campo | 257 | 74 | 0.0628 | 18 | 13 | 461 |

| 8 | Agrovila, São Benedito | 184 | 66 | 0.056 | 16 | 16 | 141 |

| 9 | Agroana | 372 | 178 | 0.151 | 44 | 38 | 349 |

| 10 | Bandeira, Minadouro | 248 | 82 | 0.0696 | 20 | 22 | 171 |

| 11 | Carretão, Deus Ajuda, Sangradouro, Pesqueiro, Varzearia | 216 | 77 | 0.0653 | 19 | 23 | 180 |

| 12 | Chafariz, Ramos, Sete Porcos, Urubamba | 208 | 67 | 0.0568 | 16 | 16 | 200 |

| 13 | Céu Azul, Capão Verde, Morro Cortado, Passagem de Carro, Varal | 157 | 65 | 0.0551 | 16 | 18 | 165 |

| N | 3,652 | 1,179 | 1.000 | 290 | 262 | 3,289 |

ID: Identification of the microarea; N: Sample size; aInformants with age ≥ 40 years and period of residing ≥ 5 years.

Of the 262 respondents, 259 (99.0%) reported the use of medicinal plants in self health care, with a minimum of 1 plant and a maximum of 250 plants among the female respondents and a minimum of 2 plants and a maximum of 54 among the male respondents. A total of 3,289 citations were recorded corresponding to 376 different plant species which belong to 285 genera and 102 families. Fabaceae (10.2%), Asteraceae (7.82%), and Lamaceae (4.89%) families were the most representative in this study (Table 3).

Table 3.

Relation of the relative importance of the plant species mentioned by informants of Nossa Senhora Aparecida do Chumbo District, Poconé, Mato Grosso, Brazil.

| Family/species | Vernacular name | Application | Preparation (administration) | Uses listed | NCS | NP | RI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ACANTHACEAE | |||||||

| 1.1. Justicia pectoralis Jacq. | Anador | pain, fever, laxative, and muscle relaxant | Infusion (I) | 36 | 2 | 3 | 0.40 |

| 2. ADOXACEAE | |||||||

| 2.1. Sambucus australis Cham. & Schltdl. | Sabugueiro | Fever and measles | Infusion (I, E) | 24 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 3. ALISMATACEAE | |||||||

| 3.1. Echinodorus macrophyllus (Kuntze.) Micheli | Chapéu-de- couro | blood cleanser, stomach, rheumatism, and kidneys | 43 | 4 | 4 | 0.67 | |

| 4. AMARYLLIDACEAE | |||||||

| 4.1. Allium cepa L. | Cebola | wound healing | Infusion (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 4.2. Allium fistulosum L. | Cebolinha | Flu | Infusion (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 4.3. Allium sativum L. | Alho | hypertension | Infusion (I) | 7 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 5. AMARANTHACEAE | |||||||

| 5.1. Alternanthera brasiliana (L.) Kuntze | Terramicina | wound healing, itching, diabetes, pain, bone fractures, throat, flu, inflammation uterine, and relaxative muscular | Infusion (I, E) | 41 | 6 | 9 | 1.20 |

| 5.2. Alternanthera dentata(Moench) Stuchlik ex R.E. Fr. | Ampicilina | wound healing and kidneys | Infusion (I, E) | 7 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 5.3. Alternanthera ficoide (L.) P. Beauv. | Doril | muscular relaxative | Infusion (I, E) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 5.4. Amaranthus aff. viridis L. | Caruru-de-porco | wound healing, pain, and kidneys | Infusion (I) | 4 | 3 | 3 | 0.50 |

| 5.5. Beta vulgaris L. | Beterraba | anemia | Infusion (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 5.6. Celosia argentea L. | Crista-de-galo | kidneys | 5 | 3 | 3 | 0.50 | |

| 5.7. Chenopodium ambrosioides L. | Erva-de-santa-maria | wound healing, heart, diabetes, bone fractures, flu, kidneys, cough, and worms | Infusion (I, E) | 102 | 7 | 8 | 1.23 |

| 5.8. Pfaffia glomerata (Spreng.) Pedersen | Ginseng-brasileiro | Obesity | Infusion (I) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 6. ANACARDIACEAE | |||||||

| 6.1. Anacardium humile A. St.– Hil. | Cajuzinho-do-campo | diabetes, dysentery, and hepatitis | Infusion (I, E) | 5 | 3 | 3 | 0.50 |

| 6.2. Anacardium occidentale L. | Cajueiro | abortive, wound healing, cholesterol, teeth, blood cleanser, diabetes, diarrhea, dysentery, and pain | Infusion (I, E) | 30 | 6 | 9 | 1.20 |

| 6.3. Astronium fraxinifolium Schott ex Spreng | Gonçaleiro | flu, hemorrhoids, and cough | Infusion and maceration (I, E) | 8 | 3 | 3 | 0.50 |

| 6.4. Mangifera indica L. | Mangueira | Bronchitis, flu, and cough | Infusion and maceration (I, E) | 11 | 2 | 3 | 0.40 |

| 6.5. Myracrodruon urundeuva (Allemão) Engl. | Aroeira | anemia, bladder bronchitis cancer, wound healing, blood cleanser, bone fractures, hernia, uterine inflammation, muscular relaxative, and cough | Infusion, maceration, and decoction (I, E) | 84 | 7 | 11 | 1.43 |

| 6.6. Spondias dulcis Parkinson | Caja-manga | scabies | Infusion (I, E) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 6.7. Spondias purpurea L. | Seriguela | wound healing and hepatitis | Infusion (I, E) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 7. ANNONACEAE | |||||||

| 7.1. Annona cordifolia Poepp. ex Maas & Westra | Araticum-abelha | Diabetes and bone fractures | Infusion and decoction (I, E) | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 7.2. Annona crassiflora Mart. | Graviola | diabetes | Infusion (I, E) | 11 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 7.3. Duguetia furfuracea (A. St.- Hil.) Saff. | Beladona-do-cerrado | pain | Infusion (I, E) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 8. APIACEAE | |||||||

| 8.1. Coriandrum sativum L. | Coentro | flu | Infusion (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 8.2. Eryngium aff. pristis Cham. & Schltdl. | Lingua-de-tucano | Tooth and muscular relaxative | Infusion (I) | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 8.3. Petroselinum crispum ((Mill) Fuss | Salsinha | flu | Infusion (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 8.4. Pimpinella anisum L. | Erva-doce | pain soothing, constipation, and kidneys | Infusion (I, E) | 12 | 3 | 3 | 0.50 |

| 9. APOCYNACEAE | |||||||

| 9.1. Aspidosperma polyneuron (Müll.) Arg. | Péroba | Stomach and laxative | Infusion and decoction (I, E) | 5 | 1 | 2 | 0.23 |

| 9.2. Aspidosperma tomentosum Mart. | Guatambu | gastritis | Infusion (I) | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 9.3. Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don | Boa-noite | mumps fever and kidneys | Infusion (I) | 8 | 3 | 3 | 0.50 |

| 9.4. Geissospermum laeve (Vell.) Miers | Pau-tenente | Diabetes and pain | Infusion (I) | 6 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 9.5. Hancornia speciosa var. gardneri (A. DC.) Müll. Arg. | Mangava-mansa | itching, diarrhea, and stomach | Decoction and maceration (I, E) | 8 | 3 | 3 | 0.50 |

| 9.6. Himatanthus obovatus (Müll. Arg.) Woodson | Angélica | anemia, wound healing, cholesterol, blood cleanser, pain, nose bleeding, hypertension, uterine inflammation, labyrinthitis, pneumonia, relaxative muscular, worms, and vitiligo | Maceration (I) | 45 | 10 | 13 | 1.87 |

| 9.7. Macrosiphonia longiflora (Desf.) Müll. Arg. | Velame-do-campo | hearth, blood cleanser, stroke, diuretic, pain, throat, muscular relaxative, and vitiligo | Decoction (I) | 5 | 6 | 8 | 1.13 |

| 9.8. Macrosiphonia velame (A. St.-Hil.) Müll. Arg. | Velame-branco | flu | Decoction (I) | 73 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 10. ARACEAE | |||||||

| 10.1 Dieffenbachia picta Schott | Comigo-ninguém-pode | pain | Maceration (E) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 10.2. Dracontium sp. | Jararaquinha | snakebite | Infusion (I) | 10 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 11. ARECACEAE | |||||||

| 11.1. Acrocomia aculeata Lodd. ex. Mart. | Bocaiuveira | heart, hepatitis, hypertension, and kidneys | Decoction and syrup (I) | 20 | 4 | 4 | 0.67 |

| 11.2. Cocos nucifera L. | Cocô-da-bahia | kidneys | Maceration (I) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 11.3. Orbignya phalerata Mart. | Babaçu | inflammation | Decoction (I) | 8 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 11.4. Syagrus oleracea (Mart.) Becc. | Guariroba | kidneys | Maceration (I) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 12. ARISTOLOCHIACEAE | |||||||

| 12.1. Aristolochia cymbifera Mart & Zucc. | Cipó-de-mil-homem | dengue, blood cleanser, stomach, kidneys, and digestive | Infusion (I) | 11 | 4 | 5 | 0.73 |

| 12.2. Aristolochia esperanzae Kuntze | Papo-de-peru | wound healing | Infusion (I) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 13. ASTERACEAE | |||||||

| 13.1. Acanthospermum australe (Loefl.). Kuntze | Carrapicho, beijo-de-boi | colic, kidneys, and runny cough | Infusion (I) | 31 | 2 | 3 | 0.40 |

| 13.2. Acanthospermum hispidum DC. | Chifre-de-garrotinho | Gonorrhea and kidneys | Infusion (I) | 5 | 2 | 3 | 0.40 |

| 13.3. Achillea millefolium L. | Dipirona, Novalgina, | pain, flu, and muscular relaxative | Infusion (I) | 13 | 3 | 4 | 0.57 |

| 13.4. Achyrocline satureioides (Lam.) DC. | Macela-do-campo | diarrhea, pain, stomach, gastritis, flu, and hypertension | Infusion (I) | 13 | 5 | 6 | 0.90 |

| 13.5. Ageratum conyzoides L. | Mentrasto | pain, labor pain, stomach, swelling in pregnant woman, rheumatism, and cough | Infusion (I) | 18 | 5 | 6 | 0.90 |

| 13.6. Artemisia vulgaris L. | Artemisia | insomnia | Infusion (I) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 13.7. Artemisia absinthium L. | Losna, nor-vômica | pain, stomach, liver, hernia, and muscular relaxative | Infusion (I) | 39 | 4 | 5 | 0.73 |

| 13.8. Baccharis trimera (Less.) DC. | Carqueja | cancer, cholesterol, diabetes, diuretic, stomach, flu, and obesity | Infusion (I) | 31 | 5 | 7 | 0.97 |

| 13.9. Bidens pilosa L. | Picão-preto | hepatitis, enteric, and kidneys | Infusion (I, E) | 20 | 3 | 3 | 0.50 |

| 13.10. Brickellia brasiliensis (Spreng.) B.L. Rob. | Arnica-do-campo | wound healing, uterine inflammation, and kidneys | Infusion (I) | 13 | 2 | 3 | 0.40 |

| 13.11. Calendula officinalis L. | Calêndula | anxiety | Infusion (I) | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 13.12. Centratherum aff. punctatum Cass. | Perpétua-roxa | muscular relaxative, and hearth | Infusion (I) | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 13.13. Chamomilla recutita (L.) Rauschert. | Camomila | soothing colic, pain, stomach, fever, and flu | Infusion (I) | 78 | 5 | 6 | 0.90 |

| 13.14. Chaptalia integerrima (Vell.) Burkart | Lingua-de-vaca | worms | Infusion (I) | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 13.15. Chromolaena odorata (L.) R.M. King & H. Rob | Cruzeirinho | colic, pain, bone fractures, pain, bone fractures, and kidneys | Infusion (I) | 7 | 3 | 4 | 0.57 |

| 13.16. Conyza bonariensis (L.) Cronquist | Voadeira | cancer itching, blood cleanser, leukemia, and worms | Infusion (I) | 15 | 4 | 5 | 0.73 |

| 13.17. Elephantopus mollis Kunth | Sussuaiá | blood cleanser, pain, and uterine inflammation | Infusion (I) | 11 | 2 | 3 | 0.40 |

| 13.18. Emilia fosbergii Nicolson | Serralha | conjunctivitis | Infusion (I) | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 13.19. Eremanthus exsuccus (DC.) Baker | Bácimo-do-campo | wound healing, stomach, bone fractures, and skin | Infusion and maceration (I, E) | 11 | 3 | 4 | 0.57 |

| 13.20. Eupatorium odoratum L. | Arnicão | wound healing, muscular relaxative, and kidneys | Infusion (I, E) | 10 | 3 | 3 | 0.50 |

| 13.21. Mikania glomerata Spreng. | Guaco | bronchitis cough | Infusion (I) | 14 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 13.22. Mikania hirsutissima DC. | Cipó-cabeludo | diabetes | Infusion (I) | 10 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 13.23. Pectis jangadensis S. Moore | Erva-do-carregador | blood cleanser and diabetes | Infusion (I) | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 13.24. Porophyllum ruderale (Jacq.) Cass. | Picão-branco | Hepatitis and kidneys | Infusion (I) | 11 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 13.25. Solidago microglossa DC. | Arnica-brasileira | wound healing, blood cleanser, pain, bone fractures, hypertension, uterine inflammation, muscular relaxative, kidneys, worms, pain, stomach, hypertension, pneumonia, constipation, and relaxative muscular | Infusion (I, E) | 82 | 8 | 15 | 1.80 |

| 13.26. Spilanthes acmella (L.) Murray | Jambú | liver | Infusion (I) | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 13.27. Tagetes minuta L. | Cravo-de-defunto | Dengue and flu | Infusion (I) | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 13.28. Taraxacum officinale L. | Dente-de-leão | blood cleanser | Infusion (I) | 18 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 13.29. Tithonia diversifolia (Hemsl.) A. Gray | Flor-da-amazônia | alcoholism, stomach, kidney, and constipation | Infusion (I) | 16 | 3 | 3 | 0.50 |

| 13.30.Vernonia condensata Baker | Figatil-caferana | cancer stomach and liver | Infusion (I) | 48 | 2 | 3 | 0.40 |

| 13.31. Vernonia scabra Pers. | Assa-peixe | bronchitis blood cleanser, fever, flu, pneumonia, cold, and cough | Infusion and syrup (I) | 38 | 2 | 7 | 0.67 |

| 13.32. Zinnia elegans Jacq. | Jacinta | pain | Infusion (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 14. BERBERIDACEAE | |||||||

| 14.1. Berberis laurina Billb. | Raiz-de-são-joão | blood cleanser and diarrhea | Decoction and bottle (I, E) | 6 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 15. BIGNONIACEAE | |||||||

| 15.1. Anemopaegma arvense (Vell.) Stellfeld & J.F. Souza | Verga-teso, Alecrim-do-campo, Catuaba | anxiety soothing kidneys | Decoction and bottle (I, E) | 13 | 2 | 3 | 0.40 |

| 15.2. Arrabidaea chica (Humb. & Bonpl.) B. Verl. | Crajirú | wound healing and blood cleanser | Infusion (I) | 6 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 15.3. Cybistax antisyphilitica (Mart.) Mart. | Pé-de-anta | fever, flu, relaxative muscular, and worms | Infusion (I) | 13 | 4 | 4 | 0.67 |

| 15.4. Jacaranda caroba (Vell.) A. DC. | Caroba | wound healing | Decoction and bottle (I, E) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 15.5. Jacaranda decurrens Cham. | Carobinha | allergy cancer wound healing, blood cleanser, diabetes, leprosy, hemorragia no nariz, inflammation uterina, and kidneys | Decoction and bottle (I, E) | 94 | 8 | 9 | 1.40 |

| 15.6. Tabebuia aurea (Silva Manso) B. & H. f. ex S. Moore | Ipê-amarelo | worms | Decoction and bottle (I) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 15.7. Tabebuia caraiba (Mart.) Bureau | Para-tudo | prostate cancer anemia, bronchitis cancer blood cleanser, diarrhea, pain, stomach, cough, and worms | Decoction and bottle (I, E) | 67 | 6 | 10 | 1.27 |

| 15.8. Tabebuia impetiginosa (Mart. ex DC.) Standl. | Ipê-roxo | prostate cancer cough | Decoction and bottle (I) | 8 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 15.9. Tabebuia serratifolia Nicholson | Piúva | prostate cancer | Decoction and bottle (I, E) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 15.10. Zeyhera digitalis (Vell.) Hochn. | Bolsa-de-pastor | Stomach | Decoction and bottle (I) | 9 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 16. BIXACEAE | |||||||

| 16.1. Bixa orellana L. | Urucum | cholesterol, stroke, bone fractures, and measles | Infusion (I) | 11 | 4 | 4 | 0.67 |

| 16.2. Cochlospermum regium (Schrank) Pilg. | Algodãozinho-do-campo | blood cleanser, stomach, bone fractures, inflammation uterina, syphilis, vitiligo, gonorrhea, and ringworm | Infusion (I) | 37 | 6 | 9 | 1.20 |

| 17. BOMBACACEAE | |||||||

| 17.1. Pseudobombax longiflorum (Mart. Et Zucc.) Rob. | Embiriçu-do-cerrado | pneumonia, cough, and tuberculosis | Infusion (I) | 17 | 3 | 3 | 0.50 |

| 17.2. Eriotheca candolleana (K. Schum.) | Catuaba | prostate cancer | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 | |

| 18. BORAGINACEAE | |||||||

| 18.1. Cordia insignis Cham. | Calção-de-velho | cough | Infusion (I) | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 18.2. Heliotropium filiforme Lehm. | Sete-sangria | thooth, blood cleanser, hypertension, and tuberculosis | Infusion (I) | 43 | 4 | 4 | 0.67 |

| 18.3. Symphytum asperrimum Donn ex Sims | Confrei | wound healing, heart, throat, and obesity | Infusion (I, E) | 10 | 4 | 4 | 0.67 |

| 19. BRASSICACEAE | |||||||

| 19.1. Nasturtium officinale R. Br. | Agrião | bronchitis | Infusion (I) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 20. BROMELIACEAE | |||||||

| 20.1. Ananas comosus (L.) Merr. | Abacaxi | diuretic and cough | Infusion (I) | 9 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 20.2. Bromelia balansae Mez | Gravatá | cough and bronhitis | Infusion (I) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 21. BURSERACEAE | |||||||

| 21.1. Commiphora myrrha (T. Nees) Engl. | Mirra | Menstruation and rheumatism | Infusion (I) | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 21.2. Protium heptaphyllum (Aubl.) Marchand | Almésica | blood cleanser, stroke, pain, muscular relaxative, rheumatism, and cough | 23 | 3 | 6 | 0.70 | |

| 22. CACTACEAE | |||||||

| 22.1. Cactus alatus Sw. | Cacto | Colic and guard delivery | Infusion (I, E) | 10 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 22.2. Opuntia sp. | Palma | column | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 | |

| 22.3. Pereskia aculeata Mill. | Oro-pro-nobis | anemia | Infusion (I) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 23. CAPPARACEAE | |||||||

| 23.1. Crataeva tapia L. | Cabaça | cough | Infusion (I) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 23.2. Cleome affinis DC. | Mussambé | diarrhea | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 | |

| 24. CARICACEAE | |||||||

| 24.1. Carica papaya L. | Mamoeiro | worms, thooth, stomach, hepatitis, muscular relaxative, and cough | Infusion (I) | 17 | 4 | 6 | 0.80 |

| 25. CARYOCARACEAE | |||||||

| 25.1. Caryocar brasiliense A. St.-Hil. | Pequizeiro | diabetes, hypertension, labyrinthitis, and obesity | 11 | 4 | 4 | 0.67 | |

| 26. CELASTRACEAE | |||||||

| 26.1. Maytenus ilicifolia Mart.ex Reissek | Espinheira-santa | uric acid, bronchitis diarrhea, stomach, gastritis, flu, and cough | Infusion (I) | 8 | 5 | 7 | 0.97 |

| 27. CECROPIACEAE | |||||||

| 27.1. Cecropia pachystachya Trécul | Embaúba | cholesterol, blood cleanser, diabetes, pain, hypertension, leukemia, pneumonia, kidneys, and cough | Infusion (I) | 38 | 6 | 9 | 1.20 |

| 28. CLUSIACEAE | |||||||

| 28.1. Kielmeyera aff. grandiflora (Wawra) Saddi | Pau-santo | anemia | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 | |

| 29. COMBRETACEAE | |||||||

| 29.1. Terminalia argentea Mart. | Pau-de-bicho | itching, diabetes, and cough | 8 | 3 | 3 | 0.50 | |

| 29.2. Terminalia catappa L. | Sete-copa | conjunctivitis | Infusion (I, E) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 30. COMMELINACEAE | |||||||

| 30.1. Commelina benghalensis L. | Capoeraba | hemorrhoids | Infusion (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 30.2. Commelina nudiflora L. | Erva-de-santa-luzia | wound healing and conjunctivitis | Infusion (I) | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 30.3. Dichorisandra hexandra (Aubl.) Standl. | Cana-de-macaco | flu, hypertension, and kidneys | Infusion (I) | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0.50 |

| 31. CONVOLVULACEAE | |||||||

| 31.1. Cuscuta racemosa Mart. | Cipó-de-chumbo | pain | Infusion (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 31.2. Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam. | Batata-doce | hearth | Infusion (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 31.3. Ipomoea (Desr.) Roem. & asarifolia Schult | Batatinha-do-brejo | Stomach and worms | Infusion (I) | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 32. COSTACEAE | |||||||

| 32.1. Costus spicatus (Jacq.) Sw. | Caninha-do-brejo | bladder diuretic, inflammation uterina, muscular relaxative, and kidneys | Infusion (I) | 40 | 3 | 5 | 0.63 |

| 33. CRASSULACEAE | |||||||

| 33.1. Kalanchoe pinnata (Lam.) Pers. | Folha-da-fortuna | allergy, bronchitis blood cleanser, and flu | Infusion and juice (I) | 11 | 2 | 4 | 0.47 |

| 34. CUCURBITACEAE | |||||||

| 34.1. Cayaponia tayuya (Cell.) Cogn. | Raiz-de-bugre | blood cleanser, pain, and hepatitis | Infusion (I) | 17 | 2 | 3 | 0.40 |

| 34.2. Citrullus vulgaris Schrad. | Melância | bladder colic | Infusion (I) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0.23 |

| 34.3. Cucumis anguria L. | Máxixe | anemia | Infusion (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 34.4. Cucumis sativus L. | Pepino | hypertension | Maceration (I) | 1 | |||

| 34.5. Cucurbita maxima Duchesne ex Lam. | Abóbora | Pain and worms | Infusion (I) | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 34.6. Luffa sp | Bucha | Anemia and kidneys | Infusion (I) | 7 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 34.7. Momordica charantia L. | Melão-de-são-caetano | bronchitis dengue, stomach, fever, flu, hepatitis, swelling in pregnant woman, malaria, muscular relaxative, and worms | Infusion (I) | 50 | 6 | 10 | 1.27 |

| 34.8. Siolmatra brasiliensis (Cogn.) Baill. | Taiuá | Ulcer | Infusion (I) | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 35. CYPERACEAE | |||||||

| 35.1. Bulbostylis capillaris (L.) C.B. Clarke | Barba-de-bode | diuretic, stomach, kidneys, and worms | Infusion (I) | 12 | 3 | 4 | 0.57 |

| 35.2. Cyperus rotundus L. | Tiririca | Pain | Infusion (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 36. DILLENIACEAE | |||||||

| 36.1. Curatella americana L. | Lixeira | wound healing, colic, diarrhea, flu, kidneys, and cough | Infusion (I, E) | 24 | 5 | 6 | 0.90 |

| 36.2. Davilla elliptica A. St.-Hil. | Lixeira-de-cipó | kidneys | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 | |

| 36.3. Davilla nitida (Vahl.) Kubitzki | Lixeirinha | delivery help, liver, hernia, and kidneys | Infusion (I) | 10 | 3 | 4 | 0.57 |

| 37. DIOSCOREACEAE | |||||||

| 37.1. Dioscorea sp. | Cará-do-cerrado | boil | Infusion (I) | 25 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 37.2. Dioscorea trifida L | Cará | blood cleanser | Infusion (I) | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 38. EBENACEAE | |||||||

| 38.1. Diospyros hispida A. DC. | Olho-de-boi | Pain and leprosy | Infusion (I) | 5 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 39. EQUISETACAE | |||||||

| 39.1. Equisetum arvense L. | Cavalinha | gastritis and kidneys | Infusion (I) | 8 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 40. ERYTHROXYLACEAE | |||||||

| 40.1 Erythroxylum aff. Daphnites Mart. | Vasoura-de-bruxa | syphilis | Infusion (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 41. EUPHORBIACEAE | |||||||

| 41.1. Croton antisyphiliticus Mart. | Curraleira | Hypertension and uterine inflammation | Infusion (I) | 6 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 41.2. Croton sp. | Curraleira-branca | uterine inflammation | Infusion (I) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 41.3. Croton urucurana Baill. | Sangra-d'água | cancer prostate cancer healing, diabetes, stomach, gastritis, uterine inflammation, kidneys, and ulcer | Maceration (I) | 37 | 5 | 9 | 1.10 |

| 41.4. Euphorbia aff. Thymifolia L. | Trinca-pedra | kidneys | Infusion (I) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 41.5. Euphorbia prostrata Aiton | Fura-pedra | kidneys | Infusion (I) | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 41.6. Euphorbia tirucalli L | Aveloz | cancer uterine inflammation | Maceration (I) | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 41.7. Jatropha sp. | Capa-rosa | diabetes | Infusion (I) | 10 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 41.8. Jatropha elliptica (Poh) Oken | Purga-de-lagarto | allergy | Infusion (I) | 38 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 41.9. Jatropha aff. Gossypiifolia L. | Pinhão-roxo | wound healing, prostrate cancer, itching, blood cleanser, stroke, snakebite, syphilis, worms, and vitiligo | Maceration(I, E) | 7 | 6 | 10 | 1.27 |

| 41.10. Jatropha urens L. | Cansansão | diabetes | Maceration (I, E) | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 41.11. Manihot esculenta Crantz | Mandioca-braba | itching | Maceration (I, E) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 41.12. Manihot utilissima Pohl. | Mandioca | itching | Maceration (I, E) | 7 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 41.13. Ricinus communis L. | Mamona | wound healing and blood cleanser | Maceration (I, E) | 8 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 41.14. Synadenium grantii Hook. f. | Cancerosa | gastritis, prostate cancer stomach, and pneumonia | Maceration (I, E) | 12 | 3 | 4 | 0.57 |

| 42. FABACEAE | |||||||

| 42.1. Acosmium dasycarpum (Volgel) Yakovlev | Cinco-folha | column, blood cleanser, pain, and kidneys | Infusion (I) | 19 | 2 | 4 | 0.47 |

| 42.2. Acosmium subelegans (Mohlenbr.) Yakovlev | Quina-gensiana | wound healing, blood cleanser, pain, liver, uterine inflammation, delivery relapse, and kidneys | Decoction (I) | 16 | 5 | 7 | 0.97 |

| 42.3. Albizia niopoides (Spr. ex Benth.) Burkart. | Angico-branco | bronhitis | Decoction (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 42.4. Amburana cearensis (Allemão) A. C. Sm. | Imburana | cough | Decoction (I) | 13 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 42.5. Anadenanthera colubrina (Vell.) Brenan | Angico | asthma, wound healing, expectorant, uterine inflammation, pneumonia, and cough | Decoction (I) | 12 | 5 | 6 | 0.90 |

| 42.6. Andira anthelminthica Benth. | Angelim | diabetes | Decoction (I) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 42.7. Bauhinia variegata L. | Unha-de-boi | kidneys | Decoction (I) | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 42.8. Bauhinia ungulata L. | Pata-de-vaca | diabetes | Infusion (I) | 11 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 42.9. Bauhinia glabra Jacq. | Cipó-tripa-de-galinha | diarrhea, dysentery, and pain | Infusion (I) | 7 | 3 | 3 | 0.50 |

| 42.10. Bauhinia rubiginosa Bong. | Tripa-de-galinha | kidneys | Infusion (I) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 42.11. Bauhinia rufa (Bong.) Steud. | Pata-de-boi | diabetes | Infusion (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 42.12. Bowdichia virgilioides Kunth | Sucupira | blood cleanser, paom, stomach, nose bleeding, cough, and worms | Bottle (I) | 20 | 4 | 6 | 0.80 |

| 42.13. Caesalpinia ferrea Mart. | Jucá | wound healing, stomach, bone fractures, and inflammation of uterine | Maceration (I, E) | 15 | 3 | 4 | 0.57 |

| 42.14. Cajanus bicolor DC. | Feijão-andu | diarrhea, stomach and worms | Infusion (I) | 8 | 2 | 3 | 0.40 |

| 42.15. Cassia desvauxii Collad. | Sene | constipation, pain, fever, uterine inflammation, and labyrinthitis | Infusion (I) | 18 | 4 | 5 | 0.73 |

| 42.16. Chamaecrista desvauxii (Collad.) Killip | Sene-do-campo | constipation, blood cleanser, pain, and fever | Infusion (I) | 10 | 2 | 4 | 0.47 |

| 42.17. Copaifera sp. | Pau-d'óleo | wound healing, kidneys, ulcer | Infusion (I) | 8 | 3 | 3 | 0.50 |

| 42.18. Copaifera langsdorffii var. glabra (Vogel) Benth. | Copaiba | bronchitis prostate cancer stroke, pain, throat, and tuberculosis | Maceration and syrup (I) | 13 | 5 | 6 | 0.90 |

| 42.19. Copaifera marginata Benth. | Guaranazinho | ulcer | Infusion (I) | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 42.20. Desmodium incanum DC. | Carrapicho | bladder itching, diarrhea, pain, hepatitis, and kidneys | Infusion (I) | 18 | 5 | 6 | 0.90 |

| 42.21. Dimorphandra mollis Benth. | Fava-de-santo-inácio | bronchitis wound healing, pain, flu, hypertension, pneumonia, rheumatism, cough, and worms | Infusion (I) | 21 | 6 | 9 | 1.20 |

| 42.22. Dioclea latifolia Benth. | Fruta-olho-de-boi | stroke | Infusion (I) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 42.23. Dioclea violacea Mart. Zucc. | Coronha-de-boi | osteoporosis | Infusion (I) | 6 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| stroke | |||||||

| 42.24. Dipteryx alata Vogel | Cumbarú | bronchitis cicartrizante, diarrhea, dysentery, pain, throat, flu, snakebite, and cough | Infusion (I) | 43 | 4 | 9 | 1.00 |

| 42.25. Galactia glaucescens Kunth | Três-folhas | column, pain, bone fractures, and kidneys | Infusion (I) | 8 | 4 | 4 | 0.67 |

| 42.26. Hymenaea courbaril L. | Jatobá-mirim | bladder bronchitis flu, pneumonia, and cough | Syrup and decoction (I) | 36 | 3 | 5 | 0.63 |

| 42.27. Hymenaea stigonocarpa Mart. ex Hayne | Jatoba-do-cerrado | bronchitis prostate cancer pain, fertilizer, flu, and cough | Syrup and decoction (I) | 31 | 5 | 6 | 0.90 |

| 42.28. Indigofera suffruticosa Mill. | Anil | ulcer | Infusion (I) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 42.29. Inga vera Willd. | Ingá | Laxative and kidneys | Infusion (I) | 5 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 42.30. Machaerium hirtum (Vell.) Stellfeld | Espinheira-santa-nativa | ulcer | Infusion (I) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 42.31. Melilotus officinalis (L) Pall. | Trevo-cheiroso | bone fractures and thyroid | Infusion (I) | 5 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 42.32. Mimosa debilis var. vestita (Benth.) Barneby | Dorme-dorme | soothing | Infusion (I) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 42.33. Mucuna pruriens (L.) DC. | Macuna | stroke | Infusion (I) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 42.34. Peltophorum dubium (Spreng.) Taub. | Cana-fistula | gastritis | Infusion (I) | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 42.35. Platycyamus regnellii Benth. | Pau-porrete | anemia | Infusion (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 42.36. Pterodon pubescens (Benth.) Benth. | Sucupira-branca | worms, pain, and stomach | SYRope, decoction and maceration (I) | 2 | 3 | 3 | 0.50 |

| 42.37. Senna alata (L.) Roxb. | Mata-pasto | throat, worms, and vitiligo | Infusion (I) | 6 | 3 | 3 | 0.50 |

| 42.38. Senna occidentalis (L.) Link | Fedegoso | blood cleanser, pain, flu, cough, and worms | Infusion (I) | 42 | 3 | 5 | 0.63 |

| 42.39. Stryphnodendron obovatum Benth. | Barbatimão 1 | wound healing | Syrup and decoction (I, E) | 57 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 42.40. Stryphnodendron adstringens (Mart.) Coville | Barbatimão 2 | bladder bronchitis, colic, stomach, bone fractures, uterine inflammation, relaxative muscular, and ulcer | Syrup and decoction (I, E) | 15 | 4 | 9 | 1.00 |

| 42.41. Tamarindus indica L. | Tamarindo | anxiety pain, thooth, laxative, osteoporosis, syphilis, and worms | Maceration and juice (I) | 30 | 6 | 7 | 1.07 |

| 43. FLACOURTIACEAE | |||||||

| 43.1. Casearia silvestris Sw. | Guaçatonga | Epilepsy and kidneys | Infusion (I) | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 44. GINKGOACEAE | |||||||

| 44.1. Ginkgo biloba L. | Ginco-biloba | vertebral | Infusion (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 45. HERRERIACEAE | |||||||

| 45.1. Herreria salsaparilha Mart. | Salsaparilha | column, blood cleanser, muscular relaxative, and kidneys | Infusion (I) | 12 | 3 | 4 | 0.57 |

| 46. HIPPOCRATEACEAE | |||||||

| 46.1. Salacia aff. elliptica (Mart. ex Schult.) G. Don | Saputa-do-brejo | pain | Infusion (I) | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 47. IRIDACEAE | |||||||

| 47.1. Eleutherine bulbosa (Mill.) Urb. | Palmeirinha | pain, hemorrhoids, cough, and blood cleanser | Infusion (I) | 11 | 2 | 4 | 0.47 |

| 48. LAMIACEAE | |||||||

| 48.1. Hyptis cf. hirsuta Kunth | Hortelã-do-campo | diabetes, stomach, flu, cough, and worms | Infusion (I) | 23 | 5 | 5 | 0.83 |

| 48.2. Hyptis paludosa St.-Hil.ex Benht. | Alevante | cold | Infusion (I) | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 48.3. Hyptis sp. | Hortelã-bravo | Diabetes and cough | Infusion (I) | 6 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 48.4. Hyptis suaveolens (L.) Poit. | Tapera-velha | pain, stomach, flu, constipation, kidneys, and worms | Infusion (I) | 42 | 5 | 6 | 0.90 |

| 48.5. Leonotis nepetifolia (L.) R. Br. | Cordão-de-são-francisco | column, hearth, blood cleanser, stomach, fever, gastritis, flu, hypertension, labyrinthitis, muscular relaxative, and kidneys | Infusion (I) | 38 | 7 | 11 | 1.43 |

| 48.6. Marsypianthes chamaedrys (Vahl) Kuntze | Alfavaca/Hortelã-do-mato | flu, hypertension, and cough | Infusion (I) | 8 | 3 | 3 | 0.50 |

| 48.7. Melissa officinalis L | Melissa | soothing | Infusion (I) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 48.8. Mentha crispa L. | Hortelã-folha-miuda | anemia, liver, cough, and worms | Infusion (I) | 16 | 4 | 4 | 0.67 |

| 48.9. Mentha pulegium L. | Poejo | bronchitis soothing fever, flu, cold, and cough | Infusion (I) | 59 | 3 | 6 | 0.70 |

| 48.10. Mentha spicata L. | Hortelã-vicki | bronchitis flu, wound healing, stomach, and worms | Infusion (I) | 24 | 4 | 5 | 0.73 |

| 48.11. Mentha x piperita L. | Hortelã-pimenta | bronchitis flu, cough and worms | Infusion (I) | 42 | 3 | 4 | 0.57 |

| 48.12. Mentha x villosa Huds. | Hortelã-rasteira | stomach, flu, cold, and worms | Infusion (I) | 86 | 3 | 4 | 0.57 |

| 48.13. Ocimum kilimandscharicum Baker ex Gürke | Alfavacaquinha | flu | Infusion (I) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 48.14. Ocimum minimum L. | Manjericão | kidneys, sinusitis, and worms | Infusion (I) | 7 | 3 | 3 | 0.50 |

| 48.15. Origanum majorana L. | Manjerona | heart | Infusion (I) | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 48.16. Origanum vulgare L. | Orégano | cough | Infusion (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 48.17. Plectranthus amboinicus (Lour.) Spreng. | Hortelã-da-folha-gorda | bronchitis flu, uterine inflammation, and cough | Infusion and syrup (I) | 7 | 3 | 4 | 0.57 |

| 48.18. Plectranthus barbatus Andrews | Boldo-brasileiro | pain, stomach, liver, and malaise | Maceration (I) | 99 | 2 | 4 | 0.47 |

| 48.19. Plectranthus neochilus Schltr. | Boldinho | stomach | Maceration (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 48.20. Rosmarinus officinalis L. | Alecrim | anxiety soothing hearth, pain, hypertension, insomnia, labyrinthitis, sluggishness memory, tachycardia, and vitiligo | Infusion and maceration (I) | 31 | 6 | 10 | 1.27 |

| 49. LAURACEAE | |||||||

| 49.1. Cinnamomum camphora (L.) Nees & Eberm. | Cânfora | pain | Infusion and maceration (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 49.2. Cinnamomum zeylanicum Breyne | Canela-da-india | aphrodisiac, tonic, obesity, and cough | Infusion (I) | 11 | 3 | 4 | 0.57 |

| 49.3. Persea americana Mill. | Abacateiro | diuretic, hypertension, and kidneys | Infusion and maceration (I) | 31 | 3 | 3 | 0.50 |

| 50. LECYTHIDACEAE | |||||||

| 50.1. Cariniana rubra Gardner ex Miers | Jequitibá | bladder wound healing, colic, pain, uterine inflammation, rheumatism, cough, and ulcer | Infusion and maceration (I) | 49 | 5 | 8 | 1.03 |

| 51. LOGANIACEAE | |||||||

| 51.1. Strychnos pseudoquina A. St.-Hil. | Quina | anemia, wound healing, cholesterol, blood cleanser, pain, stomach, bone fractures, flu, uterine inflammation, pneumonia, muscle relaxant, cough, ulcer, and worms | Decoction and maceration (I, E) | 107 | 8 | 14 | 1.73 |

| 52. LORANTHACEAE | |||||||

| 52.1. Psittacanthus calyculatus (D.C.) G. Don | Erva-de-passarinho | stroke, pain, flu, and pneumonia | Infusion and maceration (I) | 14 | 3 | 4 | 0.57 |

| 53. LYTHRACEAE | |||||||

| 53.1. Adenaria floribunda Kunth | Veludo-vermelho | kidneys | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 | |

| 53.2. Lafoensia pacari A. St.-Hil. | Mangava-braba | wound healing, diarrhea, pain, stomach, gastritis, kidneys, and ulcer | Decoction and maceration (I, E) | 73 | 5 | 7 | 0.97 |

| 54. MALPIGHIACEAE | |||||||

| 54.1. Byrsonima orbignyana A. Juss. | Angiquinho | wound healing | Decoction and maceration (I) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 54.2. Byrsonima sp. | Semaneira | pain | Infusion (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 54.3. Byrsonima verbascifolia (L.) DC. | Murici-do-cerrado | column | Infusion (I) | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| uterine inflammation | |||||||

| 54.4. Camarea ericoides A. St.-Hil. | Arniquinha | wound healing | Infusion (I) | 11 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 54.5. Galphimia brasiliensis (L.) A. Juss. | Mercúrio-do-campo | wound healing, itching, thooth, and bone fractures | Infusion (I) | 7 | 3 | 4 | 0.57 |

| 54.6. Heteropterys aphrodisiaca O. Mach. | Nó-de-cachorro | brain, wound healing, blood cleanser, impotence, muscular relaxative, and rheumatism | Decoction (I) | 23 | 5 | 6 | 0.90 |

| 54.7. Malpighia emarginata DC. | Cereja | wound healing | Infusion (I) | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 54.8. Malpighia glabra L. | Aceroleira | bronchitis dengue, stomach, fever, and flu | Infusion (I) | 24 | 4 | 5 | 0.73 |

| 55. MALVACEAE | |||||||

| 55.1. Brosimum gaudichaudii Trécul | Mama-cadela | stomach | Infusion (I) | 13 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 55.2. Gossypium barbadense L. | Algodão-de-quintal | blood cleanser, stomach, vitiligo, inflammation, and gonorrhea | Infusion (I) | 47 | 5 | 5 | 0.83 |

| 55.3. Guazuma ulmifolia var. tomentosa (Kunth) K. Schum. | Chico-magro | diarrhea, kidneys, bronchitis wound healing | Infusion and decoction (I) | 10 | 4 | 4 | 0.67 |

| 55.4. Hibiscus pernambucensis Bertol. | Algodão-do-brejo | wound healing, colic, flu, and uterine inflammation | Infusion (I) | 2 | 3 | 4 | 0.57 |

| 55.5. Hibiscus rosa-sinensis L. | Primavera | pain | Infusion (I) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 55.6. Hibiscus sabdariffa L. | Quiabo-de-angola, Hibisco | anxiety hearth, flu, tachycardia, kidneys, colic, runny, diarrhea, pain, uterine inflammation, labyrinthitis, snakebite, and pneumonia | Infusion (I) | 18 | 10 | 13 | 1.87 |

| 55.7. Helicteres sacarolha A. St.-Hil. | Semente-de-macaco | Hypertension and ulcer | Infusion (I) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 55.8. Malva sylvestris L. | Malva-branca | wound healing, conjunctivitis, runny, blood cleanser, diuretic, boil, uterine inflammation, and rheumatism | Infusion (I) | 31 | 7 | 8 | 1.23 |

| 55.9. Malvastrum corchorifolium (Desr.) Britton ex Small | Malva | tonsillitis wound healing, pain, and uterine inflammation | Infusion (I) | 13 | 4 | 4 | 0.67 |

| 55.10. Sida rhombifolia L. | Guaxuma | obesity | Infusion (I) | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 56. MELASTOMATACEAE | |||||||

| 56.1. Leandra purpurascens (DC.) Cogn. | Pixirica | rheumatism | Infusion (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 56.2. Tibouchina clavata (Pers.) Wurdack | Cibalena | pain | Infusion (I) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 56.3. Tibouchina urvilleana (DC.) Cogn. | Buscopam-de-casa | stomach | Infusion (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 57. MELIACEAE | |||||||

| 57.1. Azadirachta indica A. Juss. | Neem | diabetes | Infusion and decoction (I, E) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 57.2. Cedrela odorata L. | Cedro | wound healing | Infusion (I) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 58. MENISPERMACEAE | |||||||

| 58.1. Cissampelos sp. | Orelha-de-onça | Column and kidneys | Infusion (I) | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 59. MORACEAE | |||||||

| 59.1. Artocarpus integrifolia L.f. | Jaca | diuretic | Infusion (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 59.2. Chlorophora tinctoria (L.) Gaudich. ex Benth. | Taiúva | osteoporosis and muscular relaxative | Infusion (I) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 59.3. Dorstenia brasiliensis Lam. | Carapiá | wound healing, colic, thooth, blood cleanser, dysentery, pain, flu, laxative, menstruation, pneumonia, relapse delivery, and kidneys | Infusion (I) | 41 | 7 | 12 | 0.50 |

| 59.4. Ficus brasiliensis Link. | Figo | gastritis | Infusion (I) | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 59.5. Ficus pertusa L. f. | Figueirinha | stomach | Infusion (I) | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 60. MUSACEAE | |||||||

| 60.1. Musa x paradisiaca L. | Bananeira-de-umbigo | bronchitis anemia and pain | Infusion and syrup (I) | 9 | 3 | 3 | 0.50 |

| 61. MYRTACEAE | |||||||

| 61.1. Eucalyptus citriodora Hook. | Eucálipto | bronchitis diabetes, fever, flu, sinusitis, and cough | Infusion and syrup (I) | 22 | 3 | 6 | 0.70 |

| 61.2. Eugenia pitanga (O. Berg) Kiaersk. | Pitanga | pain, throat, flu, and kidneys | Infusion (I) | 10 | 3 | 4 | 0.57 |

| 61.3. Psidium guajava L. | Goiabeira | diarrhea | Infusion (I) | 19 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 61.4. Psidium guineense Sw. | Goiaba-áraça | pain, diarrhea, and hypertension | Infusion (I) | 11 | 3 | 3 | 0.50 |

| 61.5. Syzygium aromaticum (L.) Merr. & L. M. Perry | Cravo-da-india | Throat and cough | Infusion (I) | 5 | 1 | 2 | 0.23 |

| 61.6. Syzygium jambolanum (Lam.) DC. | Azeitona-preta | cholesterol | Decoction (I, E) | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 62. NYCTAGINACEAE | |||||||

| 62.1. Boerhavia coccinea L. | Amarra-pinto | bladder icterus, inflammation uterina, and kidneys | Infusion (I) | 22 | 2 | 4 | 0.47 |

| 62.2. Mirabilis jalapa L. | Maravilha | heart, pain, and hypertension | Infusion (I) | 8 | 2 | 3 | 0.40 |

| 63. OLACACEAE | |||||||

| 63.1. Ximenia americana L. | Limão-bravo | Trush and diuretic | Infusion (I) | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 64. OPILIACEAE | |||||||

| 64.1. Agonandra brasiliensis Miers ex Benth. & Hook f. | Pau-marfim | uterine inflammation | Decoction (I, E) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 65. ORCHIDACEAE | |||||||

| 65.1. Vanilla palmarum (Salzm. ex Lindl.) Lindl. | Baunilha | hypertension | Infusion (I) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 65.2. Oncidium cebolleta (Jacq.) Sw. | Orquidea | pain | Infusion (I) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 66. OXALIDACEAE | |||||||

| 66.1. Averrhoa carambola L. | Carambola | hypertension | Infusion (I) | 8 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 66.2. Oxalis aff. hirsutissima Mart. ex Zucc. | Azedinha | obesity | Infusion (I) | 9 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 67. PAPAVERACEAE | |||||||

| 67.1. Argemone mexicana L. | Cardo-santo | hypertension | Infusion (I) | 8 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 68. PASSIFLORACEAE | |||||||

| 68.1. Passiflora alata Curtis | Maracujá | Infusion (I) | 9 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 | |

| 68.2. Passiflora cincinnata Mast. | Maracujá-do-mato | soothing hypertension | Infusion (I) | 5 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 69. PEDALIACEAE | |||||||

| 69.1 Sesamum indicum L. | Gergelim | stomach, liver, gastritis, ulcer, and worms | Infusion and maceration (I) | 12 | 2 | 5 | 0.53 |

| 70. PHYLLANTHACEAE | |||||||

| 70.1. Phyllanthus niruri L. | Quebra-pedra | kidneys | Infusion (I) | 32 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 71. PHYTOLACCACEAE | |||||||

| 71.1. Petiveria alliacea L. | Guiné | rheumatism | Infusion (I, E) | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 72. PIPERACEAE | |||||||

| 72.1. Piper callosum Ruiz & Pav | Ventre-livre/elixir paregórico | kidneys | Infusion (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 72.2. Piper cuyabanum C. DC. | Jaborandi | pain, stomach, and loss of hair | Infusion (I, E) | 10 | 3 | 3 | 0.50 |

| 72.3. Pothomorphe umbellata (L.) Miq. | Pariparoba | blood cleanser, stomach, liver, and pneumonia | Infusion (I) | 11 | 3 | 3 | 0.50 |

| 73. PLANTAGINACEAE | |||||||

| 73.1. Plantago major L. | Tanchagem | heart, pain, and laxative | Infusion (I) | 16 | 3 | 3 | 0.50 |

| 74. POACEAE | |||||||

| 74.1. Andropogon bicornis L. | Capim-rabo-de-lobo | uterine inflammation | Infusion (I) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 74.2. Coix lacryma-jobi L. | Lácrimas-de-nossa-senhora | kidneys | Infusion (I, E) | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 74.3. Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) Stapfc | Capim-cidreira | soothing blood cleanser, pain, stomach, expectorant, fever, flu, hypertension, muscular relaxative, kidneys, tachycardia, and cough | Infusion and juice (I) | 49 | 5 | 12 | 1.30 |

| 74.4. Cymbopogon nardus (L.) Rendle. | Capim-citronela | flu, cough, and tuberculosis | Infusion (E) | 11 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 74.5. Digitaria insularis (L.) Mez ex Ekman | Capim-amargoso | wound healing, stomach, bone fractures, and rheumatism | Infusion (I) | 14 | 3 | 4 | 0.57 |

| 74.6. Eleusine indica (L.) Gaertn. | Capim-pé-de-galinha | Hypertension and swelling in pregnant woman | Infusion (I) | 6 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 74.7. Imperata brasiliensis Trin. | Capim-sapé | diabetes, pain, hepatitis, kidneys, and vitiligo | Infusion (I) | 12 | 5 | 5 | 0.83 |

| 74.8. Melinis minutiflora P. Beauv. | Capim-gordura | dengue, blood cleanser, stroke, flu, kidneys, sinusitis, cough, and tumors | Infusion (I) | 31 | 7 | 8 | 1.23 |

| 74.9. Oryza sativa L. | Arroz | bladder | Infusion (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 74.10. Saccharum officinarum L. | Cana-de-açúcar | kidneys, anemia, and hypertension | Infusion (I) | 2 | 3 | 3 | 0.50 |

| 74.11. Zea mays L. | Milho | bladder kidneys | Infusion (I) | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 75. POLYGALACEAE | |||||||

| 75.1. Polygala paniculata L. | Bengué | rheumatism | Infusion (I) | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 76. POLYGONACEAE | |||||||

| 76.1. Coccoloba cujabensis Wedd. | Uveira | diuretic | Infusion (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 76.2. Polygonum cf. punctatum Elliott | Erva-de-bicho | wound healing, dengue, stomach, fever, flu, and hemorrhoids | Infusion (I) | 41 | 5 | 6 | 0.90 |

| 76.3. Rheum palmatum L. | Ruibarbo | blood cleanser, dysentery, pain, and snakebite | Infusion (I) | 6 | 4 | 4 | 0.67 |

| 76.4. Triplaris brasiliana Cham. | Novatero | diabetes | Infusion (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 77. POLYPODIACEAE | |||||||

| 77.1. Phlebodium decumanum (Willd.) J. Sm. | Rabo-de-macaco | diuretic, hepatitis, and kidneys | Infusion (I) | 9 | 2 | 3 | 0.40 |

| 77.2. Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn | Samambaia | colic, blood cleanser, and rheumatism | Infusion (I) | 8 | 3 | 3 | 0.50 |

| 77.3. Pteridium sp. | Samambaia-de-cipo | rheumatism | Infusion (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 78. PONTEDERIACEAE | |||||||

| 78.1. Eichhornia azurea (Sw.) Kunth | Aguapé | ulcer | Infusion (I) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 79. PORTULACACEAE | |||||||

| 79.1. Portulaca oleracea L. | Onze-horas | hypertension | Infusion (I) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 80. PROTEACEAE | |||||||

| 80.1. Roupala montana Aubl. | Carne-de-vaca | muscular relaxative | Infusion (I) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 81. PUNICACEAE | |||||||

| 81.1. Punica granatum L. | Romã | colic, diarrhea, pain, throat, inflammation uterina, and kidneys | Infusion and maceration (I, E) | 41 | 3 | 6 | 0.70 |

| 82. RHAMNACEAE | |||||||

| 82.1. Rhamnidium elaeocarpum Reissek | Cabriteiro | anemia, diarrhea, diuretic, pain, stomach, and worms | Infusion (I) | 37 | 5 | 6 | 0.90 |

| 83. ROSACEAE | |||||||

| 83.1. Rosa alba L. | Rosa-branca | wound healing, pain, and uterine inflammation | Infusion and maceration (I, E) | 6 | 3 | 3 | 0.50 |

| 83.2. Rosa graciliflora Rehder & E. H. Wilson | Rosa-amarela | pain | Infusion and maceration (I, E) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 83.3. Rubus brasiliensis Mart. | Amoreira | cholesterol, hypertension, labyrinthitis, menopause, obesity, osteoporosis, and kidneys | Infusion and tintura (I) | 38 | 6 | 7 | 1.07 |

| 84. RUBIACEAE | |||||||

| 84.1. Chiococca alba (L.) Hitchc. | Cainca | pain, flu, and rheumatism | Infusion (I) | 8 | 3 | 3 | 0.50 |

| 84.2. Cordiera edulis (Rich.) Kuntze | Marmelada | worms | Maceration and syrup (I) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 84.3. Cordiera macrophylla (K. Schum.) Kuntze | Marmelada-espinho | worms | Maceration and syrup (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 84.4. Cordiera sessilis (Vell.) Kuntze | Marmelada-bola | Flu and worms | Maceration and syrup (I) | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 84.5. Coutarea hexandra (Jacq.) K. Schum. | Murtinha | diarrhea | Infusion (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 84.6. Genipa americana L. | Jenipapo | appendicitis bronchitis diabetes and kidneys | Infusion and syrup (I) | 8 | 4 | 4 | 0.67 |

| 84.7. Guettarda viburnoides Cham. & Schltdl. | Veludo-branco | blood cleanser and ulcer | Infusion (I) | 5 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 84.8. Palicourea coriacea (Cham.) K. Schum. | Douradinha-do-campo | prostate cancer hearth, blood cleanser, diuretic, flu, hypertension, insomnia, relaxative muscular, and kidneys | Infusion (I) | 62 | 7 | 9 | 1.30 |

| 84.9. Palicourea rigida Kunth | Doradão | Kidneys and cough | Infusion and decoction (I) | 5 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 84.10. Rudgea viburnoides (Cham.) Benth. | Erva-molar | column, thooth, blood cleanser, dysentery, rheumatism, and kidneys | Infusion (I) | 44 | 5 | 6 | 0.90 |

| 84.11. Tocoyena formosa (Cham. & Schltdl.) K. Schum. | Jenipapo-bravo | kidneys | Infusion (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 84.12. Uncaria tomentosa (Willd. ex Roem. & Schult.) DC. | Unha-de-gato | intoxication, rheumatism, and kidneys | Infusion (I) | 10 | 3 | 3 | 0.50 |

| 85. RUTACEAE | |||||||

| 85.1. Citrus aurantiifolia (Christm.) Swingle | Lima | soothing hearth, and hypertension | Infusion (I) | 8 | 2 | 3 | 0.40 |

| 85.2. Citrus limon (L.) Osbeck | Limão | colic, diabetes, pain, liver, flu, hypertension, and cough | Infusion (I) | 17 | 5 | 7 | 0.97 |

| 85.3. Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck | Laranja | soothing wound healing, fever, flu, pneumonia, and thyroid | Infusion (I) | 30 | 4 | 6 | 0.80 |

| 85.4. Ruta graveolens L. | Arruda | colic, conjunctivitis, pain, stomach, fever, gastritis, nausea, and laxative muscular | Infusion (I) | 57 | 4 | 8 | 0.93 |

| 85.5. Spiranthera odoratissima A.St.-Hil. | Manacá | rheumatism | Infusion (I) | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 85.6. Zanthoxylum cf. rhoifolium Lam. | Mamica-de-porca | diabetes, diarrhea, hemorrhoids, and muscular relaxative | Decoction (I, E) | 12 | 4 | 4 | 0.67 |

| 86. SALICACEAE | |||||||

| 86.1. Casearia silvestris Sw. | Chá-de-frade | blood cleanser, pain, and fever | Infusion (I) | 10 | 1 | 3 | 0.30 |

| 87. SAPINDACEAE | |||||||

| 87.1. Dilodendron bipinnatum Radlk. | Mulher-pobre | bone fractures | Infusion (I) | 5 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| uterine inflammation | |||||||

| 87.2. Magonia pubescens A. St.-Hil. | Timbó | wound healing, pain, and cough | Maceration (I, E) | 7 | 2 | 3 | 0.40 |

| 87.3. Serjania erecta Radk. | Cinco-pontas | column, muscular relaxative, and kidneys | Infusion (I) | 9 | 2 | 3 | 0.40 |

| 87.4. Talisia esculenta (A. St.-Hil.) Radlk. | Pitomba | column, pain, and rheumatism | Infusion (I) | 6 | 2 | 3 | 0.40 |

| 88. SAPOTACEAE | |||||||

| 88.1. Pouteria glomerata (Miq.) Radlk. | Laranjinha-do-mato | fever | Infusion (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 88.2. Pouteria ramiflora (Mart.) Radlk. | Fruta-de-viado | Ulcer and kidneys | Infusion (I) | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 89. SCROPHULARIACEAE | |||||||

| 89.1. Bacopa sp. | Vicki-de-batata | kidneys | Infusion (I) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 89.2. Scoparia dulcis L. | Vassorinha | bladder wound healing, hearth, blood cleanser, diabetes, pain, bone fractures, swelling in pregnant woman, pneumonia, kidneys, syphilis, and cough | Infusion (I) | 81 | 7 | 12 | 1.50 |

| 90. SIMAROUBACEAE | |||||||

| 90.1. Simaba ferruginea A. St.-Hil. | Calunga | anemia, wound healing, diabetes, digestive, pain, stomach, obesity, ulcer, and worms | Maceration (I) | 31 | 7 | 9 | 1.30 |

| 90.2. Simarouba versicolor A. St.-Hil. | Pé-de-perdiz | wound healing and uterine inflammation | Decoction (I, E) | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 91. SIPARUNACEAE | |||||||

| 91.1. Siparuna guianensis Aubl. | Negramina | pain, fever, and flu | Infusion (I) | 20 | 2 | 3 | 0.40 |

| 92. SMILACACEAE | |||||||

| 92.1. Smilax aff. brasiliensis Spreng. | Japecanga | Column and rheumatism | Infusion (I) | 5 | 1 | 2 | 0.23 |

| 93. SOLANACEAE | |||||||

| 93.1. Capsicum sp. | Pimenta | Pain and hemorrhoids | Infusion (I, E) | 14 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 93.2. Nicotiana tabacum L. | Fumo | thyroid | Infusion (I, E) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 93.3. Physalis sp. | Tomate-de-capote | hepatitis | Infusion (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 93.4. Solanum americanum Mill. | Maria-pretinha | worms | Infusion (I) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 93.5. Solanum lycocarpum A. St.-Hil. | Fruta-de-lobo | Gastritis and ulcer | Infusion and maceration (I) | 6 | 1 | 2 | 0.23 |

| 93.6. Solanum sp. | Jurubeba | column, stomach, and liver | Infusion (I) | 8 | 2 | 3 | 0.40 |

| 93.7. Solanum sp. | Urtiga | boi | Infusion (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 93.8. Solanum melongena L. | Berinjela | cholesterol | Infusion and maceration (I) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 93.9. Solanum tuberosum L. | Batata-inglesa | Pain and gastritis | Infusion and maceration (I, E) | 13 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 93.10. Solanum viarum Dunal. | Joá-manso | Hemorrhoids | Infusion (I) | 7 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 94. TILIACEAE | |||||||

| 94.1. Apeiba tibourbou Aubl. | Jangadeira | liver | Decoction (I, E) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 94.2. Luehea divaricata Mart. | Açoita-cavalo | uric acid, column, blood cleanser, throat, flu, hemorrhoids, intestine, pneumonia, muscular relaxative, kidneys, cough, and tumors | Decoction and syrup (I) | 58 | 7 | 12 | 1.50 |

| 95. ULMACEAE | |||||||

| 95.1. Trema micrantha (L.) Blume | Piriquiteira | wound healing | Decoction (I, E) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 96. VERBENACEAE | |||||||

| 96.1. Casselia mansoi Schau | Saúde-da-mulher | thooth, blood cleanser, uterine inflammation, and menstruation | Infusion (I) | 9 | 3 | 4 | 0.57 |

| 96.2. Duranta repens L. | Pingo-de-ouro | diabetes | Infusion (I, E) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 96.3. Lantana camara L. | Cambará | cold and cough | Decoction (I) | 22 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 96.4. Lippia alba (Mill.) N. E. Br. ex Britton & P. Wilson | Erva-cidreira | soothing hearth, thooth, blood cleanser, pain, flu, hypertension, tachycardia, and cough | Infusion (I) | 75 | 5 | 9 | 1.10 |

| 96.5. Phyla sp. | Chá-mineiro | conjunctivitis, blood cleanser, pain, fever, muscular relaxative, rheumatism, and kidneys | Infusion (I) | 19 | 4 | 7 | 0.87 |

| 96.6. Priva lappulacea (L.) Pers. | Pega-pega | Stomach and sinusitis | Infusion (I) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 96.7. Stachytarpheta aff. cayennensis (Rich.) Vahl | Gervão | bronchitis blood cleanser, stomach, liver, bone fractures, gastritis, flu, constipation, relaxative muscular, cough, and worms | Infusion (I) | 80 | 6 | 11 | 1.33 |

| 96.8. Stachytarpheta sp. | Rabo-de-pavão | relaxative muscular | Infusion (I) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 96.9. Vitex cymosa Bert.ex Spregn. | Tarumeiro | blood cleanser, diarrhea, pain, and stomach | Infusion (I) | 8 | 3 | 4 | 0.57 |

| 97. VIOLACEAE | |||||||

| 97.1. Anchietea salutaris A. St.-Hil. | Cipó-suma | column, blood cleanser, fever, intoxication, and vitiligo | Infusion (I) | 18 | 4 | 5 | 0.73 |

| 97.2. Hybanthus calceolaria (L.) Schulze-Menz. | Poaia-branca | cough | Infusion (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 98. VITACEAE | |||||||

| 98.1. Cissus cissyoides L. | Insulina-de-ramo | diabetes | Infusion (I) | 10 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 98.2. Cissus gongylodes Burch. ex Baker | Cipó-de-arráia | relaxative muscular | Infusion (I) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 98.3. Cissus sp. | Rabo-de-arráia | hypertension | Infusion (I) | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 98.4. Cissus sp. | Sofre-do-rim-quem-quer | inflammation uterina, relaxative muscular, and kidneys | Infusion (I) | 5 | 3 | 3 | 0.50 |

| 99. VOCHYSIACEAE | |||||||

| 99.1. Callisthene fasciculata Mart. | Carvão-branco | Hepatitis and icterus | Decoction (I, E) | 10 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 99.2. Qualea grandiflora Mart. | Pau-terra | Diarrhea and pain | Decoction (I, E) | 5 | 2 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 99.3. Qualea parviflora Mart. | Pau-terrinha | diarrhea | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 | |

| 99.4. Salvertia convallariodora A. St.-Hil. | Capotão | diarrhea, diuretic, hemorrhoids, and relaxative muscular | Decoction (I, E) | 4 | 4 | 4 | 0.67 |

| 99.5. Vochysia cinnamomea Pohl | Quina-doce | flu | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 | |

| 99.6. Vochysia rufa Mart. | Pau-doce | blood cleanser, diabetes, diarrhea, laxative, obesity, kidneys, cough, and worms | Decoction, Infusion (I, E) | 25 | 6 | 8 | 1.13 |

| 100. LILIACEAE | |||||||

| 100.1. Aloe barbadensis Mill. | Babosa | Cancer, prostate cancer, wound healing, diabetes, stomach, bone fractures, gastritis, hepatitis, laxative, and rheumatism | Syrup and maceration (I, E) | 87 | 5 | 9 | 1.10 |

| 101. ZAMIACEAE | |||||||

| 101.1. Zamia boliviana (Brongn.) A. DC. | Maquiné | stomach | Infusion (I) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 102. ZINGIBERACEAE | |||||||

| 102.1. Alpinia speciosa (J. C. Wendl.) K. Schum. | Colônia | soothing hearth, fever, flu, and hypertension | Infusion (I) | 36 | 4 | 5 | 0.73 |

| 102.2. Curcuma longa L. | Açafrão | column, diuretic, pain, stomach, and hepatitis | Infusion and maceration (I) | 18 | 4 | 5 | 0.73 |

| 102.3. Zingiber officinale Roscoe | Gengibre | pain, flu, sinusitis, and cough | Infusion and maceration (I) | 26 | 2 | 4 | 0.47 |

I: Internal, E: External; NSC: Number of body systems treated by species; NCS: number of body systems. NP: Number of properties of the species; RI: Relative importance of the species.

3.1. Relative Importance (RI)

The RI of the species cited by 262 respondents from NSACD ranged from 0.17 to 1.87. A total of 261 species had RI ≤ 0.5; 80 species, RI from 0.51 to 1.0; 30 species, RI from 1.1 to 1.5, and 4 species with RI from 1.51 to 2.0, among the latter, three species were native to Brazil. The species with RI ≥ 1.5, were Himatanthus obovatus (Müll. Arg.) Woodson (1.87), Hibiscus sabdariffa L. (1.87), Solidago microglossa DC. (1.80), Strychnos pseudoquina A. St.-Hil. (1.73), Dorstenia brasiliensis Lam., Scoparia dulcis L., and Luehea divaricata Mart. (1.50 each), as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Species with the highest values of relative importance.

| Family | Species | Application/citation | RF | RI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apocynaceae | Himatanthus obovatus (Müll. Arg.) Woodson | anemia (1), wound healing (7), cholesterol (3), blood cleanser (9), pain (4), nose bleeding (1), hypertension (4), uterine inflammation (5), labyrinthitis (6), muscle relaxant (2), worms (1), vitiligo (1), and pneumonia (1) | 45 | 1.87 |

| Malvaceae | Hibiscus sabdariffa L | anxiety/heart (1), flu (1), tachycardia (1), kidneys (1), cramps (3), discharge (1), diarrhea (1), pain (1), inflammation uterine (2), labyrinthitis (3), snakebite (1), and pneumonia (2) | 18 | 1.87 |

| Asteraceae | Solidago microglossa DC. | wound healing (53), blood cleanser (11), pain (2), bone fractures (1), hypertension (1), uterine inflammation (3), muscle relaxant (6), kidneys (3), and worms (2) | 82 | 1.8 |

| Loganiaceae | Strychnos pseudoquina A. St.-Hil. | anemia (46), wound healing (3), cholesterol (1), blood cleanser (16), pain (13), stomach (3), bone fractures (1), flu (2), uterine inflammation (1), pneumonia (1), muscle relaxant (1), cough (10), ulcer (1), and worms (8) | 107 | 1.73 |

| Moraceae | Dorstenia brasiliensis Lam. | wound healing (1), colic (1), tooth ache (1), blood cleanser (4), dysentery (1), pain (7), flu (2), laxative (3), menstruation (1), pneumonia (6), relapse delivery (13), and kidneys (1) | 41 | 1.5 |

| Plantaginaceae | Scoparia dulcis L. | heart (6), blood cleanser (1), diabetes (1), pain (16), bone fractures (47), swelling in pregnant woman (4), pneumonia (1), kidneys, ( 1) syphilis (3), and cough (1) | 55 | 1.5 |

| Malvaceae | Luehea divaricata Mart. | uric acid (18), vertebral column (2), blood cleanser (1), throat (1), flu (1), hemorrhoids (7), intestine (1), pneumonia (8), muscle relaxant (2), kidneys (3), cough (10), and tumors (4) | 58 | 1.5 |

RF: Relative frequency; RI: Relative importance of the species.

3.2. Informant Consensus Factor (ICF)

In the disease categories according to CID, 10th ed., we observed that ICF values ranged from 0.43 to 0.77, with the exception of disease category included in CID VI (diseases of the nervous system), which was 0.13. The ICF for CID VI ranged between 0.13 and 0.78 (mean = 0.62, SD = 0.16, 95% CI: 0.53–0.70). The highest consensus value obtained was for the category related to injuries, poisoning, and some other consequences of external causes (ICF = 0.78), with 65 species and 286 citations. Three species were more common, namely, S. dulcis and S. microglossa (“Brazilian arnica”), with 49 citations each and L. pacari (manga-brava) with 42 citations. The main ailments addressed in this category were inflammation, pain, and gastric disorders.

Out of 20 disease categories, there were citations for 18 therapeutic indications, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Categories of diseases, indications, form of use, preparation and the informant consensus factor of the main medicinal plants from Nossa Senhora Aparecida do Chumbo District, Poconé, Mato Grosso, Brazil.

| Disease category/CID, 10th ed. | Medicinal plants | Main indications | Main forms of use | Part utilized/ State of the plant | Species/citations | ICF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Injuries, poisoning, and certain other consequences of external causes— XIX | Scoparia dulcis L. Solidago microglossa D. C Lafoensia pacari A. St.-Hil. | inflammation and pain | Inf, Dec, Mac, and Tin | L, Wp, Rt (Fr, Dr) | 65/286 | 0.78 |

| Mental and behavioural disorders —V | Chamomilla recutita (L.) Rauschert. | soothing | Dec and Inf | L (In, Sc) | 20/85 | 0.77 |

| Symptoms, signs, and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings not elsewhere classified—XVIII | Macrosiphonia longiflora (Desf.) Müll. Arg. | blood depurative | Inf, Dec, and Mac | Rz (Fr, Dr) | 176/713 | 0.75 |

| Diseases of the genitourinary system —XIV | Palicourea coriacea (Cham.) K. Schum. | Kidneys and diuretic | Inf, Dec, and Syr | L (Fr, Dr) | 132/533 | 0.75 |

| Diseases of the digestive system—XI | Plectranthus barbatus Andrews | stomach, pain, liver, and malaise | Dec, Inf, Mac, and Juc | L (Fr, Dr) | 113/428 | 0.74 |

| Other infectious and parasitic diseases—I | Chenopodium ambrosioides L. | verminose | Inf, Mac, and Juc | L (Fr,Dr) | 82/300 | 0.73 |

| Diseases of the respiratory system—X | Mentha pulegium L. | flu, bronchitis, colds, and cough | Dec, Inf, Mac, and Syr | L (Fr, Dr) | 88/303 | 0.71 |

| Pregnancy, childbirth, and the puerperium—XV | Dorstenia brasiliensis Lam. | childbirth | Dec, Inf, and Syr | Rz (Fr, Dr) | 9/28 | 0.70 |

| Diseases of the circulatory system—IX | Alpinia speciosa (J. C. Wendl.) K. Schum. | Hypertension and heart | Inf and Mac | L (Fr, Dr) | 56/180 | 0.69 |

| Some disorders originating in the perinatal period—XVI | Bidens pilosa L. | Hepatitis and enteric | Dec and Inf | L (In, Sc) | 3/7 | 0.67 |

| Diseases of blood and blood forming organs and certain disorders involving the immune system—III | Strychnos pseudoquina A. St.-Hil. | anemia | Inf, Mac, and Syr | B (Fr, Dr) | 15/38 | 0.62 |

| Diseases of the eye and the surrounding structures—VII | Malva sylvestris L. | Discharge and conjuctivitis | Inf and Tin | L (Fr, Dr) | 6/14 | 0.61 |

| Diseases of endocrine of nutritional and metabolic origins—IV | Cissus cissyoides L. | diabetes | Inf | L (Fr, Dr) | 47/109 | 0.57 |

| Diseases of the ear and mastoid process—VIII | Himatanthus obovatus (Müll. Arg.) Woodson | labyrinthitis | Inf | L (Fr, Dr) | 7/15 | 0.57 |

| Diseases of musculoskeletal and connective tissue—XIII | Solidago microglossa DC. | bone fractures | Dec, Inf, Mac, and Tin | L (Fr, Dr) | 70/146 | 0.52 |

| Diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue—XII | Dioscorea brasiliensis Willd. | furuncules | Dec, Inf, Mac, Tin, and Out | Rz (Fr, Dr) | 29/51 | 0.44 |

| Neoplasia (tumors)—II | Aloe barbadensis Mill. | wound healing | Dec, Inf, Mac, Tin, and Out | L (Fr, Dr) | 22/38 | 0.43 |

| Diseases of the nervous system—VI | Macrosiphonia longiflora (Desf.) Müll. Arg. | leakage | Inf | 14/16 | 0.13 |

CID, 10th ed. categories of diseases in chapters according to International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th. edition [25]; ICF: informant consesus factor; Inf: infusion, Dec: decoction, Syr: syrup, Mac: maceration, Sal: salad, Tin: tinture, Juc: juice, Out: others (compression and bath). L: leave; Wp: whole plant; Rt: root; Rz: rhizome; B: bark. State of the plant: Fr: fresh; Dr: dried.

4. Discussion

In the present study, almost all the respondents (99%) claimed to know and use medicinal plants. Surveys conducted in other countries had reported values ranging from 42% to 98% depending on the region and country of the study [25–27]. Due to the low level of knowledge of traditional medicine in national capitals, ethnobotanical surveys in many developing countries including Brazil, primarily prefer to evaluate small communities or rural hometowns, whose population having knowledge and practical experience with traditional medicine are proportionately higher (between 80 and 100%) [28–30].

The high percentage of folk knowledge of medicinal plants identified in Brazil may be due to factors such as lower influence of the contemporary urban lifestyle and the strength of cultural traditions in the rural communities [31]. In fact, with the process of industrialization and migration to the cities, a significant part of traditional culture is maintained more in the communities farther from the metropolis via oral transmission of the knowledge of CAM and family traditions. Transmission and conservation of CAM knowledge is more pronounced in Brazil due to high degree of biodiversity.

One of the most important aspects of this research is the documentation of high number of taxa (285 genera and 102 families) and species (376) mentioned by the informants as medicinal. These findings confirmed the existence of the great diversity of plants used for therapeutic purpose and preserved traditional culture, as stated by Simbo [32]. It is worth mentioning here the presence of 8 (eight) local medicinal plant expert informants/healers among the 262 respondents in this study. These local expert informants/healers account for a significant number of citations (43 to 250) in this study. In Brazil, as in other countries, rural communities have developed knowledge about the medicinal and therapeutic properties of natural resources and have contributed to the maintenance and transmission of the ethnopharmacological knowledge within the communities.

The most representative plant families are Fabaceae (10.2%), Asteraceae (7.82%), and Lamiaceae (4.89%). These results are in accordance with other ethnobotanical surveys conducted in the tropical regions [33, 34] including Brazil [7, 35]. Furthermore, the results from our study are also in conformity with the findings of the most comprehensive ethnobotanical survey conducted by V. J. Pott and A. Pott in the Brazilian Pantanal region [19].