Abstract

Objective

To retrospectively evaluate the feasibility and effectiveness of three-tube insertion for the treatment of postoperative gastroesophageal anastomotic leakage (GEAL).

Materials and Methods

From January 2007 to January 2011, 28 cases of postoperative GEAL after an esophagectomy with intrathoracic esophagogastric anastomotic procedures for esophageal and cardiac carcinoma were treated by the insertion of three tubes under fluoroscopic guidance. The three tubes consisted of a drainage tube through the leak, a nasogastric decompression tube, and a nasojejunum feeding tube. The study population consisted of 28 patients (18 males, 10 females) ranging in their ages from 36 to 72 years (mean: 59 years). We evaluated the feasibility of three-tube insertion to facilitate leakage site closure, and the patients' nutritional benefit by checking their serum albumin levels between pre- and post-enteral feeding via the feeding tube.

Results

The three tubes were successfully placed under fluoroscopic guidance in all twenty-eight patients (100%). The procedure times for the three tube insertion ranged from 30 to 70 minutes (mean time: 45 minutes). In 27 of 28 patients (96%), leakage site closure after three-tube insertion was achieved, while it was not attained in one patient who received stent implantation as a substitute. All patients showed good tolerance of the three-tube insertion in the nasal cavity. The mean time needed for leakage treatment was 21 ± 3.5 days. The serum albumin level change was significant, increasing from pre-enteral feeding (2.5 ± 0.40 g/dL) to post-enteral feeding (3.7 ± 0.51 g/dL) via the feeding tube (p < 0.001). The duration of follow-up ranged from 7 to 60 months (mean: 28 months).

Conclusion

Based on the results of this study, the insertion of three tubes under fluoroscopic guidance is safe, and also provides effective relief from postesophagectomy GEAL. Moreover, our findings suggest that three-tube insertion may be used as the primary procedure to treat postoperative GEAL.

Keywords: GEAL, Three-tube insertion, Interventional procedure, Esophageal and cardiac carcinoma

INTRODUCTION

Although the amounts of postoperative anastomotic leakage can be rather slight, it is a major source of mortality and morbidity (1). In patients with GEAL, quality of life as well as the prognosis is very poor. The leading causes of death in patients with GEAL are infection and nutritional deficiency (2, 3). GEAL is still a therapeutic problem (4, 5) and the most effective treatment option for intra thoracic GEAL is still controversial. Hence, there is no standardized treatment algorithm. Some surgeons recommend aggressive surgery, while others prefer conservative approaches, such as perianastomotic drainage, total parenteralnutrition, nasogastric decompression, and the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics (6). In this study, we determined the feasibility and effectiveness of using a three-tube insertion for the treatment of postoperative GEAL. The effect on GEAL treatment was evaluated by the time interval of the leakages' closure, and the effect on nutritional status was evaluated by measuring serum albumin levels.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study population included 28 patients suffering from postoperative GEAL and underwent three-tube insertion under fluoroscopic guidance from January 2007 to January 2011. The 28 patients underwent an esophagectomy with intrathoracic esophagogastric anastomotic procedures for esophageal and cardiac carcinoma. The 28 patients consisted of 18 males and 10 females ranging in age from 36 to 72 years (mean age: 59 years). Three of the patients were TNM stage I esophageal carcinoma patients, nine were TNM stage II a, eleven were TNM stage II b, and five were TNM stage III. A frozen-section analysis of resected margins by a competent pathologist was available, and resection margins were found to be cancer-free in all cases. The retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our hospital and the Ethics Committee of the Institute for Medical Science. The procedure was explained to all of the patients in detail, and a written consent was obtained from all patients prior to the procedure. The patients were divided into two groups: one group contained the patients with leakage within 14 postoperative days, and the other group patients with leakage at more than 14 postoperative days (22). Twenty of the 28 patients experienced acute leakages, and 8 patients had chronic leakages. Signs and symptoms were present in all patients (100%) and included high fever in 26 patients, shortness of breath in 18 patients, chest pain in eight patients, and arrhythmia in six patients. The leakages in the 24 patients (85.7%) were confirmed by first radiographic contrast examination. Four (14.2%) patients initially had negative contrast examination results, but they were all eventually proven to have anastomotic leakage by repeated radiographic contrast examinations 3 to 7 d later. The leakage in all patients was first confirmed by a computed tomography (CT) examination (Fig. 1A). The three tubes were removed after the leak's closure was testified by CT findings.

Fig. 1.

Intrathoracic anastomotic leak testified by CT at 1 week postoperation.

Fistula was located in pleural cavity (A, black arrow). Fistula closed at 25 days (B).

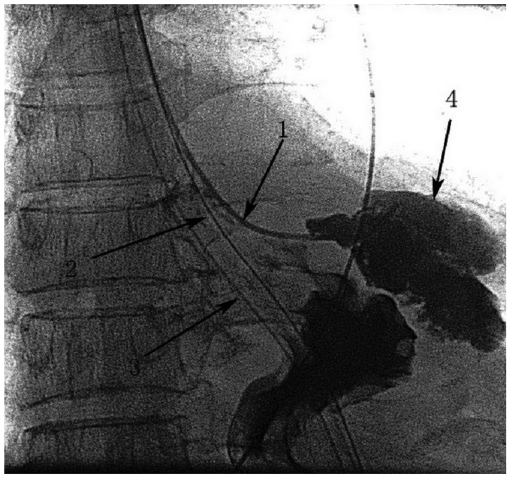

Interventional Procedure (Fig. 2)

Fig. 2.

Drain tube (arrow 1) inserted through fistula with fluoroscopic guidance and distal tip of drain tube was positioned at bottom of abscess cavity (arrow 4).

Feeding nasojejunum tube (arrow 2) and cases of nasogastric decompression tube (arrow 3) were placed during interventional operation for postoperative enteral nutrition supply and digestive slice drainage.

Nasogastric Placement of the Drainage Tube through the Leak

All the procedures were performed by two interventional radiologists. The patients were in the supine position which allowed an easy performance of interventional maneuvers, and optimal fluoroscopic visualization of the leak. A 0.035-inch guidewire (Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) and a 4F H1 catheter (Terumo, Japan) were advanced into the esophageal passage through one nasal cavity under fluoroscopic guidance (DSA, Angiostar; Siemens, Germany). The fluid collections aspirated through the catheter were sent for bacterial culture testing. The prosthesis delivery system was then advanced over the guidewire until a 10F Flocare polyurethane un-weighted feeding tube (Nutricia, Export BV, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) was sent into the vomica. We suggested that the backward distance of the tube should be less than 5 cm. The Flocare tube was connected to a low-pressure continuous vacuum pump whose negative pressure was about 8-10 mm Hg. The fluid collection was examined every day for color and total quantity.

Nasogastric Placement of the Feeding Tube into the Jejunum

A 4F H1 catheter (Terumo, Japan) was advanced into the esophageal passage through the ipsilateral nasal cavity. When gthe H1 catheter entered the stomach, an Amplatz superstiff exchange guidewire (Medi-Tech/Boston Scientific, MA, USA) was then inserted via the catheter into the distal portion of the jejunum. And 10F Flocare polyurethane unweighted feeding tube (Nutricia, Switzerland) was then inserted into the jejunum using the guidewire. Contrast medium was injected through the Flocare feeding tube to verify the success of the manipulation. Essential nutrients were poured into the jejunum through the Flocare feeding tube.

A nasogastric decompression tube was placed under fluoroscopic guidance when we applied this treatment to keep the digestive slice from affluxing into the leakage.

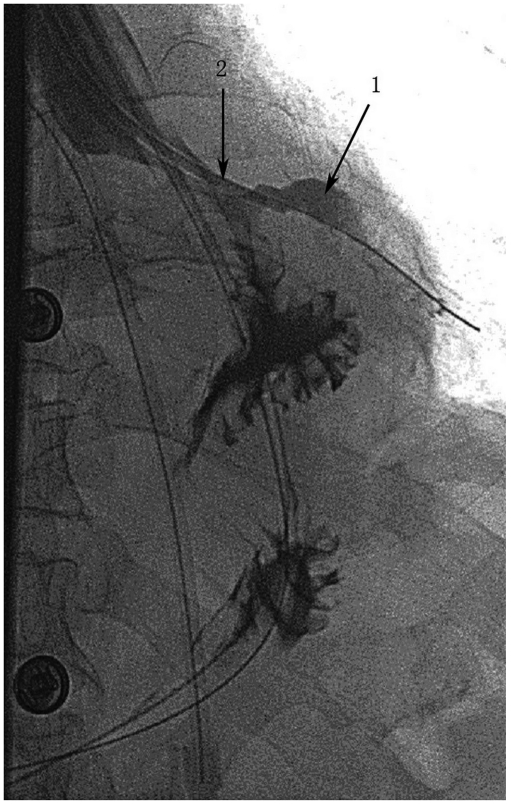

When daily volume of the fluid drainage was reduced to 5-10 mL, the drainage tube could be gradually pulled back (Fig. 3) because the adhesion between the lung and the chest wall had already formed at the end of the tube. Under the fluoroscopic guidance, the drainage tube was pulled back from the distal end to the proximal end of the vomica.

Fig. 3.

Eleven days later, fistula (arrow 1) got smaller, after changing position of drainage tube (arrow 2) to keep optimum drainage.

Immediate technical success was defined as the successful insertion of the three-tube without any problems. Clinical success was defined as closure of the leakage site (Fig. 4), as confirmed by a follow-up CT examination (Fig. 1B). A patients' nutritional benefit was evaluated by the serum albumin level change between the pre- and post-enteral feeding via the feeding tube. The differences in the means were evaluated by t tests.

Fig. 4.

Fistula closed on 25 days. Nasojejunum enteral supports tube (arrow 1) was retained for enteral nutrition.

RESULTS

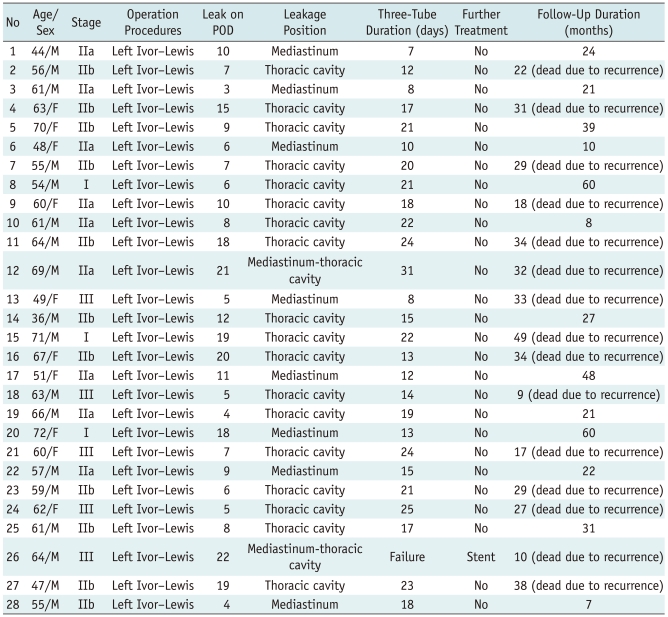

Immediate technical success was achieved in all patients (28/28 patients). The chronic group (> 14 postoperative day) showed a high incidence of leakage site in the thoracic cavity (8/8 = 100%), but the acute group (< 14 postoperative day) showed a low incidence of leakage site in the thoracic cavity (13/20 = 65%) (Table 1). All patients had a good tolerance of the three-tube in the nasal cavity. Side effects such as shortness of breath were not seen in any patient. Only slight nasal mucosa diabrosis was seen in two patients.

Table 1.

Data in Fluoroscopically Guided by Three-Tube Insertion for Relief of Postoperative Gastroesophageal Anastomotic Leakage

Note.- POD = postoperative days

The procedure times for three-tube insertion ranged from 30 to 70 min. (mean time: 45 min) and was dependent on the detection of the leakage site. Twenty-seven patients (27/28 = 96.4%) experienced symptomatic relief, while in one patient, though a successful three-tube insertion was achieved, the leakage did not close and the patient suffered from serious sepsis. A covered nitinol stent (Micro-Tech Co, Nanjing, China) was successfully placed to cover the leakage site 31 d after receiving the three-tube treatment. Sepsis was then under control in 3 weeks. However, the patient died 10 months after placement due to sudden uncontrollable hematemesis. The mean time interval of the leakage treatment was 21 ± 3.5 d. The median follow-up time was 28.2 months (range 7-60 months). No patient was diagnosed with leak recurrences.

The patient's nutritional benefit was shown by the increasing serum albumin level after enteral feeding via the nasojejunum feeding tube. The mean serum albumin level was 2.5 ± 0.40 g/dL (1.87-3.68 g/dL) in a 14 day of a pre-enteral feeding tube period and 3.7 ± 0.51 g/dL (2.52-4.86 g/dL) in 14 days post-enteral feeding via the feeding tube. The differences in the mean significantly increased between pre- and post-enteral feeding via the feeding tube (p < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

Although GEAL occurs in less than 10% of patients, it still remains the most feared complication of esophageal resection because of its associated high morbidity and mortality (7, 8). Although several methods such as surgical re-exploration and repair and/or more conservative approaches like perianastomotic drainage or broad-spectrum antibiotics have been used, no consensus has been reached on the best methods of treatment, and the rate of treatment failure remains high. It may correlate with general nutritive status, anastomotic technique, anastomotic stoma tension, anastomotic manner, blood circulation lesion of the esophageal or gastric wall, digestive tract obstruction, intrathoracic infection, and so on (9-11). HU et al. (12) divides the pathophysiological process of GEAL into 3 stages: diffusion, contained, the elimination of multi-cavity vomicas. The anastomotic leakage closed within durations of drainage tube insertion with hyperalimentation. In our opinion GEAL is a special kind of pyothorax. The key in leak management is adequate and effective drainage. When the leakage was limited in the pleural cavity, routine chest tube could achieve adequate drainage. But previous studies had revealed that most of the contained leaks were limited to the mediastinum (7, 8, 13). It is difficult to deal with this type of leakage because abscess cavities close to the mediastinum are difficult to reach by a conventional chest tube. Nasogastric placement of the drainage tube through the leak in our study may be a helpful treatment for this type of leak. We successfully applied the drainage tube through the leak for the treatment of intrathoracic anastomotic leaks in 28 patients. Twenty-seven patients (27/28 = 96.4%) experienced symptomatic relief. The mean time interval of the leakage treatment was 21 ± 3.5 d which is much shorter than 32-99 d in the previous study (14, 15).

In our study one patient received placement of self-expanding metallic coated stents after failure of the three-tube treatment. The GEAL was located in the mediastinum and thoracic cavity. The vomicas were huge, coated, and interlinked. Effective drainage could not be achieved. The stent was placed on the 31 d after receiving three-tube treatment. The patient died on 10 months after placement due to uncontrollable hematemesis. Previous studies (16, 17) revealed that certain problems might be associated with stent placement and removal: insufficient closure of the leaks, stent migration and development of strictures after stent removal, severe complications: such as bleeding and food blockage, hard removal because of the growth of granulation tissue, et al. But other studies (18-21) concluded that stent placement has been shown to be an excellent treatment in patients without sepsis and large mediastinal abscess formation. In our view, the leakage in our study can be deemed as optimal and, it is not very suitable to insert the stent leader. Once the stent is placed, it had to be got out which is afflicting for patient. Some patients died of a large amount of haematemesis due to the repeated friction between the stent and fistula (13) over the course of the stents' dislodgment. Moreover, we know the accurate time of the closure of the leakages while the stent treatment can't support it. We can monitor the leakage by contrast-medium injection while the stent treatment can't.

The enteric feeding might contribute to the general nutritional correction from the postsurgical status, and this might contribute to the closure of anastomotic leakage. A routine jejunostomy to nutritional support is a traumatic method. But the nasogastric placement of nutritious tube of jejunum under the fluoroscopic guidance can avoid the injury of the jejunum. Moreover total parenteral nutrition is expensive and it has a high rate of complications. The enteral feeding allows for a high serum albumin level compared to total parenteral nutrition (22). In our study, the patient nutrition benefit showed a significantly increased serum albumin level after enteral feeding (p < 0.001). Han et al. (22) reported that they reached a successfull relief of the postoperative gastrointestinal anastomotic obstruction and leakage by fluoroscopically guided feeding tube insertion in thirty-four patients. In our view food intake can irritate the mucosa at the anastomotic site. In addition, the digestive slice can continuously enter the chest space from the fistula. As intrathoracic pleural adhesion has not formed, it is easy to result in diffusion, chemical, and purulent pleuritis; and, eventually, severe sepsis, consumption, and death. In our study, no patient suffered severe sepsis. Ott et al. (23) had reported a success rate for fluoroscopic placement of 90%, with a tube placed into the jejunum in 53% of patients and placed into the duodenum in 47% of the patients. In the present study, the tubes were placed fluoroscopically in the jejunum in all patients, and the mean procedure time was 45 minutes. Moreover, the endoscopic and fluoroscopic placement of postpyloric feeding tubes can be performed safely and accurately at the bedside for critically ill patients (24). Fluoroscopic placement requires less additional sedation, whereas endoscopic placement allows direct visualization of the gastric and duodenal anatomy, and it can be performed without additional X-ray support (24). In our study, fluoroscopic guidance using a catheter and guidewire allowed for the anastomotic sites to be found easily and there were unhindered passages of the catheter into the jejunum because the catheter has a considerably smaller diameter than the endoscopy instrument.

The nasogastric decompression tube was routinely placed when we applied this kind of conservative treatment. Jiang et al. (13) reported that the nasogastric decompression tubes were unnecessary in this management of the intrathoracic esophagogastric anastomotic leak because the drainage volume of the tube was low. However, our clinical observation revealed that the drainage volume of the nasogastric decompression tube was not low. So we retained the tube.

There are some limitations in our study. One of the limitations was the retrospective and nonrandomized study design. In the coming days, a prospective and randomized study will be designed to evaluate clinical efficacy in three-tube vs stent placement for the treatment of postoperative GEAL. The other one was that some patients feel discomfort. But in our study all patients had a good tolerance of three-tube in nasal cavity. Shortness of breath was seen in no patient. Only slight nasal mucosa diabrosis was seen in two patients.

In conclusion, three-tube insertion under fluoroscopic guidance was found to provide safe and effective relief of GEAL. We suggest that three-tube insertion should be considered as an alternative therapeutic option for patients having GEAL.

References

- 1.Orringer MB, Marshall B, Iannettoni MD. Transhiatal esophagectomy: Clinical experience and refinements. Ann Surg. 1999;230:392. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199909000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Urschel JD. Esophagogastrectomy anastomotic leaks complicating esophagectomy: a review. Am J Surg. 1995;169:634–640. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)80238-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dehn TC, Menon K. Diagnosis and conservative management of intrathoracic leakage after oesophagectomy. Br J Surg. 1999;86:427. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1999.1055e.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright CD, Kucharczuk JC, O'Brien SM, Grab JD, Allen MS. Predictors of major morbidity and mortality after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer: a Society of Thoracic Surgeons General Thoracic Surgery Database risk adjustment model. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137:587–595. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whooley BP, Law S, Alexandrou A, Murthy SC, Wong J. Critical appraisal of the significance of intrathoracic anastomotic leakage after esophagectomy for cancer. Am J Surg. 2001;181:198–203. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00559-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turkyilmaz A, Eroglu A, Aydin Y, Tekinbas C, Muharrem Erol M, Karaoglanoglu N. The management of esophagogastric anastomotic leak after esophagectomyfor esophageal carcinoma. Dis Esophagus. 2009;22:119. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2008.00866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crestanello JA, Deschamps C, Cassivi SD, Nichols FC, Allen MS, Schleck C, et al. Selective management of intrathoracic anastomotic leak after esophagectomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129:254. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Urschel JD, Blewett CJ, Bennett WF, Miller JD, Young JE. Handsewn or stapled esophagogastric anastomoses after esophagectomy for cancer: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Dis Esophagus. 2001;14:212–217. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2050.2001.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dan HL, Bai Y, Meng H, Song CL, Zhang J, Zhang Y, et al. A new three-layer-funnel-shaped esophagogastric anastomosis for surgical treatment of esophageal carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:22–25. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patil PK, Patel SG, Mistry RC, Deshpande RK, Desai PB. Cancer of the esophagus: esophagogastric anastomotic leak-a retrospective study of predisposing factors. J Surg Oncol. 1992;49:163–167. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930490307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Junemann-Ramirez M, Awan MY, Khan ZM, Rahamim JS. Anastomotic leakage post-esophagogastrectomy for esophageal carcinoma: retrospective analysis of predictive factors, management and influence on longterm survival in a high volume centre. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2005;27:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu Z, Yin R, Fan X, Zhang Q, Feng C, Yuan F, et al. Treatment of intrathoracic anastomotic leak by nose fistula tube drainage after esophagectomy for cancer. Diseases of the Esophagus. 2011;24:100–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2010.01102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang F, Yu MF, Ren BH, Yin GW, Zhang Q, Xu L. Nasogastric Placement of Sump Tube Through the Leak for the Treatment of Esophagogastric Anastomotic Leak After Esophagectomy for Esophageal Carcinoma. J Surg Res. 2011;171:448–451. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryan JM, Murphy BL, Boland GW, Mueller PR. Use of transgluteal route for percutaneous abscess drainage in acute diverticulitis to facilitate delayed surgical repair. AJR. 1998;170:1189–1193. doi: 10.2214/ajr.170.5.9574582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams RN, Hall AW, Sutton CD, Ubhi SS, Bowrey DJ. Management of Esophageal Perforation and Anastomotic Leak by Transluminal Drainage. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:777–781. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1472-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanatas AN, Aldouri A, Hayden JD. Anastomotic leak after oesophagectomy and stent implantation: a systematic review. Oncol Rev. 2010;4:159–165. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tuebergen D, Rijcken E, Mennigen R, Hopkins AM, Senninger N, Bruewer M. Treatment of thoracic esophageal anastomotic leaks and esophageal perforations with endoluminal stents: efficacy and current limitations. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1168–1176. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0500-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Babor R, Talbot M, Tyndal A. Treatment of upper gastrointestinal leaks with a removable, covered, self-expanding metallic stent. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2009;19:e1–e4. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e318196c706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leers JM, Vivaldi C, Schafer H, Bludau M, Brabender J, Lurje G, et al. Endoscopic therapyfor esophageal perforation or anastomotic leak with a self-expandable metallic stent. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:2258. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0302-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karbowski M, Schembre D, Kozarek R, Ayub K, Low D. Polyflex self-expanding, removable plastic stents: assessment of treatment efficacy and safety in a variety of benign and malignant conditions of the esophagus. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1326–1333. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9644-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dai YY, Gretschel S, Dudeck O, Rau B, Schlag PM, Hunerbein M. Treatment of oesophageal anastomotic leaks by temporary stenting with self-expanding plastic stents. Br J Surg. 2009;96:887–891. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han YM, Kim CY, Yang DH, Kwak HS, Jin GY. Fluoroscopically Guided Feeding Tube Insertion for Relief of Postoperative Gastrointestinal Anastomotic Obstruction and Leakage. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2006;29:395–400. doi: 10.1007/s00270-005-0095-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ott DJ, Mattox HE, Gelfand DW, Chen MY, Wu WC. Enteral feeding tubes: placement by using fluoroscopy and endoscopy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;157:769–771. doi: 10.2214/ajr.157.4.1909832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foote JA, Kemmeter PR, Prichard PA, Baker RS, Paauw JD, Gawel JC, et al. A randomized trial of endoscopic and fluoroscopic placement of postpyloric feeding tube in critically ill patients. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2004;28:154–157. doi: 10.1177/0148607104028003154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]