Abstract

We conducted a four-wave prospective study of Palestinian adults living in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and East Jerusalem, interviewed between 2007 and 2009 at 6-month intervals to explore transactional relationships among resource loss (i.e., intra- and inter-personal resource loss) and psychological distress (i.e., PTSD and depression symptoms). Initially, 1196 Palestinians completed the first wave interview and 752 of these participants completed all four interviews. A cross-lagged panel design was constructed to model the effects of trauma exposure on both resource loss and psychological distress and the subsequent reciprocal effects of resource loss and psychological distress across four time waves. Specifically, resource loss was modeled to predict distress, which in turn was expected to predict further resource loss. Structural equation modeling was used to test this design. We found that psychological distress significantly predicts resource loss across shorter, 6-month time waves, but that resource loss predicts distress across longer, 12-month intervals. These findings support the Conservation of Resources theory’s corollary of loss spirals.

Keywords: resource loss, PTSD, depression, loss spirals, political violence, cross-lagged panel analysis

The ubiquity of traumatic stress after mass trauma events has the potential for major deleterious effects on the broader community. Over the past several decades, research investigating mass trauma events has expanded dramatically and has yielded valuable information regarding key variables involved in posttraumatic stress responses, with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression being the most commonly studied sequelae (e.g., Bleich, Gelkopf, & Solomon, 2003; Canetti et al., 2010; Hobfoll et al., 2009; Shalev & Freedman, 2005). However, research examining the mechanisms underlying the relationship between trauma and psychological symptoms has been limited and key transactional patterns (e.g., Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) have been proposed but seldom studied.

One theoretical model that provides a framework for deepening our understanding of the relationship between mass trauma and posttraumatic response is the Conservation of Resources (COR; Hobfoll, 1998; 2001) theory. COR theory provides a framework for understanding the interrelationships between some of the most frequently identified etiological variables including extent of traumatic exposure, loss of tangible and psychosocial resources, and psychopathology. The central tenet of COR theory is that individuals strive to obtain, retain, and protect those things (resources) they most value, both material and psychosocial. COR theory predicts that stress occurs when individuals lose resources, face the threat of resource loss, or fail to gain resources following significant resource investment. Traumatic events often result in rapid and substantive material and psychosocial resource loss. Such loss means that traumatic events will have severe initial impact and that the ongoing nature of loss will produce a wake of subsequent and ongoing deleterious effects (Hobfoll et al., 2009).

Since its development, COR theory has garnered support as a theory for understanding the consequences of major and traumatic stressors across a variety of populations including survivors of political violence in Israel, Gaza, and the West Bank (Hobfoll et al., 2009; Palmieri, Galea, Canetti-Nisim, Johnson, & Hobfoll, 2008); the 9/11 terrorist attacks (Bonanno, Galea, Bucciarelli, & Vlahov, 2007); and natural disasters (Benight et al., 1999; Kaniasty & Norris, 1993). Across these populations, the strength of relationships among traumatic exposure, resource loss, and psychopathology have been clearly and consistently established. However, what has been lacking is multi-wave research that can identify transactional patterns of resource loss and their relationship to the development of posttraumatic responses, as these would shed greater light on directionality of the trauma, loss, and distress sequence.

Loss Spirals

COR theory posits that exposure to traumatic events, especially mass casualty events that impact whole communities, is inherently threatening to people’s resources, both tangible and psychological (Hobfoll, 1998; 2001). As a result of such traumas, victims often lose tangible goods (e.g., destruction of property), supportive persons in their lives (e.g., displacement, evacuation, death), and psychological resources such as hope and optimism about the future. Indeed, empirical research has supported the hypothesis that exposure to traumatic events deteriorates valued resources (see Hobfoll, 2001). COR theory predicts that this initial resource loss will cause further deterioration of remaining resources, as individuals lose the very resources required to support their resilience and coping. COR theory thus predicts loss spirals where stress is severe or chronic (Hobfoll, 1998) as would also be consistent with Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984; see also Lazarus, DeLongis, Folkman, & Gruen, 1985) predictions about the stress-distress process.

A key factor that amplifies loss spirals is the development of psychological symptoms and disorders, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression, which are common responses to traumatic events. Though the above studies have theorized that more resource loss will predict greater psychological distress, emerging research has at the same time found that psychological distress may lead to resource loss. Johnson and colleagues (2007) demonstrated this important chain of the loss spiral. They found that PTSD predicted later resource loss, even when controlling for past resource loss and depressive symptoms. Similarly, Kaniasty and Norris (1993) found that, following disasters, initial distress led to an immediate increase of social support, but that support levels quickly became depleted. Continued empirical explorations of the interrelationship of resource loss and psychological distress over time will provide greater insight into specific mechanisms and pathways by which loss cycles manifest themselves.

The Palestinian Context and the Present Research

Because COR theory is particularly suited to explain community-based and widespread trauma, its application to political violence and terrorism in the West Bank and Gaza is well-founded as these regions have been in a state of political upheaval for decades. Since the first uprising (Intifada) against Israeli rule in 1987, over 7,000 Palestinians have been killed (B’Tselem, 2010) and more than 63,000 have been injured (PCHR, 2010). Up to 80% of Palestinians have been directly exposed to or impacted by acts of political violence in the West Bank (Giacaman, Shannon, Saab, Arya, & Boyce, 2007) and 38% have experienced high levels of exposure to violence (Abdeen, Qasrawi, Nabil, & Shaheen, 2008). Due to these high levels of exposure to political violence and conflict, understanding the transactional nature of resource loss and psychological distress over time could yield valuable information about the trajectories of these variables and a more conclusive understanding of these relationships.

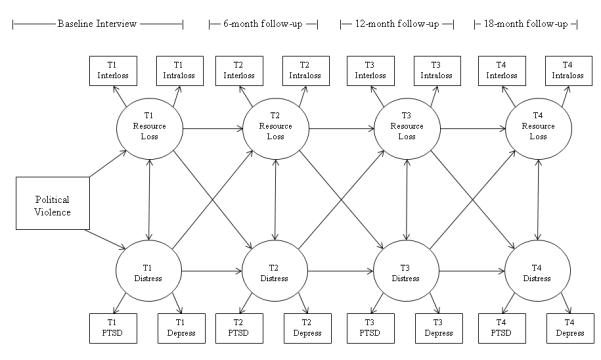

Though resource loss, PTSD, and depression have been examined extensively in this population, research solely investigates unidirectional relationships (e.g., resource loss or trauma exposure predicting distress). Prior studies with the same data used in the present investigation have identified relationships among exposure to traumatic stress, resource loss, and psychological distress (Canetti et al., 2010; Hobfoll, Hall, & Canetti, 2010). However, this previous research did not examine the loss spiral concept offered by COR theory, that trauma leads to both resource loss and psychological distress, and that this psychological distress leads to greater resource loss. In order to evaluate the transactional relationship between resource loss and psychological distress over time, we proposed a four-wave (18 month span), cross-lagged structural equation model (see Figure 1). In this model, we predicted that prior exposure to political violence would predict initial (baseline) levels of both resource loss (as measured by intrapersonal and interpersonal resource loss) and psychological distress (as assessed by PTSD and depression symptoms). We further predicted bidirectional relationships between resource loss and psychological distress such that resource loss would predict subsequent psychological distress and that psychological distress would, in turn, predict subsequent resource loss over each measurement lag. Thus, the present study is the first empirical test of the construct of loss spirals in a mass casualty context. It is also perhaps the only large scale, four-wave study of a region experiencing mass casualty.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized Structural Model of Transactional Relationships among Resource Loss and Psychological Distress. Interloss = interpersonal resource loss, Intraloss = intrapersonal resource loss, Distress = psychological distress, Depress = depression.

Method

Sampling and Procedures

A stratified 3-stage cluster random sampling strategy for Palestinian adults living in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and East Jerusalem was used to recruit participants. In the first stage, we selected 60 clusters with populations of 1,000 or more Palestinians with probabilities proportional to size and subsequently stratified this sample by district and type of community (i.e., urban, rural, and refugee camp). Second, 20 households within each cluster were randomly selected. Third, individuals were randomly selected from each household using Kish Tables (which provide within-household randomization of participants). Research team members visited each sampled household at least 3 times to complete the interviews. These team members described the study, obtained written informed consent, and compensated the participants with the equivalent of approximately $5 (U.S.D.).

We attempted four face-to-face interviews with each participant by same-sex interviewers who were trained in interview techniques. Interviewers were Arabs from the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Gaza and all held college degrees or their equivalent. Research supervisors reviewed all item content and explained item meaning to train interviewers on the nature of the questionnaires. Interviewers were also trained to demonstrate neutral responses to participant answers so as not to influence them. Interviewers worked in pairs interviewing each other, for experience being the interviewer and interviewee prior to data collection. The first wave of interviews were conducted from September 17 to October 16, 2007, the second wave of interviews (6-month follow up) were conducted between April 16 and May 17, 2008, the third wave (12-month follow-up) of interviews from October 15 to November 1, 2008, and the final wave of interviews (18 months later) were conducted from May 29 to June 10, 2009. In several prior studies, a structured interview consisting of the self-report measures used here was administered, after having been translated and back-translated into Arabic. Measures were found to have sound psychometric properties in this population; means, standard deviations, and score ranges for each measure are included in Table 1. Each interview lasted approximately 45 to 60 minutes. The institutional review boards of Kent State University, the University of Miami, Rush University Medical Center, and the University of Haifa approved this study.

Table 1.

Demographics and Study Variables (N = 1196)

| Variable | % | M (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Women | 52.0 | ||

| Men | 48.0 | ||

| Age | 35.01 (12.68) | 18 – 80 | |

| Education | 2.22 (1.15) | 1 – 4 | |

| Income | 2.70 (0.81) | 1 – 3 | |

| Marital Status | |||

| Single | 27.6 | ||

| Married | 68.3 | ||

| Divorced | 1.0 | ||

| Widowed | 2.7 | ||

| T1 Exposure | 1.45 (1.21) | 0 – 7 | |

| T1 Intraloss | 4.71 (3.76) | 0 – 15 | |

| T1 Interloss | 2.85 (2.80) | 0 – 12 | |

| T1 PTSD | 21.58 (9.41) | 0 – 51 | |

| T1 Depression | 10.41 (6.08) | 0 – 27 | |

| T2 Intraloss | 3.57 (3.56) | 0 – 15 | |

| T2 Interloss | 2.22 (2.57) | 0 – 12 | |

| T2 PTSD | 20.85 (9.05) | 0 – 49 | |

| T2 Depression | 9.76 (6.30) | 0 – 26 | |

| T3 Intraloss | 3.21 (3.51) | 0 – 15 | |

| T3 Interloss | 2.19 (2.75) | 0 – 12 | |

| T3 PTSD | 18.66 (9.57) | 0 – 47 | |

| T3 Depression | 8.51 (6.28) | 0 – 27 | |

| T4 Intraloss | 3.16 (3.72) | 0 – 15 | |

| T4 Interloss | 2.04 (2.75) | 0 – 12 | |

| T4 PTSD | 18.99 (9.95) | 0 – 50 | |

| T4 Depression | 8.96 (6.56) | 0 – 27 |

Note. Exposure = Exposure to Political Violence. Intraloss = intrapersonal resource loss. Interloss = interpersonal resource loss. T1 = baseline interview. T2 = 6-month follow-up. T3 = 12-month follow-up. T4 = 18-month follow-up

Participants

Participants for this study were 1196 Palestinian adults living in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and East Jerusalem who completed the first of four full interviews. Of this initial sample, 999 agreed to be contacted for future interviews. At the 6-month follow-up, 889 participants completed interviews and 110 did not participated due to change in address (n = 18), refusal to participate (n = 52), unavailability for interview (n = 36), being in prison (n = 2), or being “martyred” (n = 2), yielding a response rate of 89%. At the 12-month follow-up, the 889 participants who completed previous interview were approached. Of those, 98 additional participants did not complete interviews due to change in address (n = 15), refusal to participate (n = 32), unavailability for interview (n = 48), or illness (n = 3). This yielded a response rate of 89% between the second and third interviews. At the 18-month follow-up, the 792 people who completed the third interview were approached; however, 40 did not participate due to change in address (n = 7), refusal to participate (n = 11), unavailability for interview (n = 19), illness (n = 2), or death (n = 1), yielding a sample of 752 remaining participants at the fourth time wave, and a response rate of 95% between the 12- and 18-month follow-ups. The overall rate of attrition for this study was 37.18%. See Table 1 for specific demographic information. The final sample paralleled the known Palestinian Authority population demographics in age, economic status, and sex (Palestinian National Authority, 2008), suggesting that we contacted a representative sample of the target population.

When compared to the demographic characteristics of the final 752 study participants, the attrition sample (n = 444) significantly differed in terms of income level. Specifically, those who dropped out of this study reported higher household incomes (M = 1.82, SD = .85) than those who remained in the study (M = 1.63, SD = .78), t(1160) = 3.71, p < .001, and were also less likely to be married χ2(1, N = 1192) = 5.41, p = .02. The attrition sample also endorsed significantly less exposure to political violence at baseline (M = 1.34, SD = 1.19 versus M = 1.52, SD = 1.21, t(1150) = −2.47, p = .01) and lower levels of baseline PTSD symptoms (M = 20.42, SD = 9.73 versus M = 22.47, SD = 9.15, t(1145) = −3.24, p = .001) than did the participants who remained in the study. These two groups did not significantly differ on any other variable of interest.

Measures

Demographics questionnaire

Demographic information collected at the baseline interview included sex (coded 0 = male, 1 = female), marital status (coded 1 = single/divorced/separated/widowed, 2 = married), age, education (less than high school, high school graduate, some college, college graduate), and income. To assess income, participants were asked to report their combined household income as compared to the monthly average household income in the Palestinian Authority (2,500 New Israeli Shekel) on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (much less than average) to 5 (much more than average).

Exposure to political violence

Levels of exposure to political violence within the year prior to the baseline interview were assessed by summing the total number of times the participants experienced the following: a death of a family member or friend, an injury to a family member or friend, an injury to themselves, or witnessing Israeli attacks or violence among Palestinian factions.

Resource loss

Resource loss was assessed using a 9-item scale adapted from the Conservation of Resources Evaluation (COR-E; Hobfoll & Lilly, 1993. Participants were asked to what extent they had lost a variety of psychosocial resources in the year prior to the baseline interview as a result of the military occupation or violence among political factions. Participants were instructed to answer the extent to which they have experienced each item using a Likert-type scale from 0 (did not lose at all) to 3 (lost very much); items were then summed into two subscales consistent with past research (Canetti et al., 2010): intrapersonal resource loss (including five items such as “feeling that you are a successful person,” “hope,” and “a sense of control in your life”) and interpersonal resource loss (including four items such as “stability of your family,” “intimacy with one family member or more,” and “feeling that you are a person of great value to other people”). In this study, the obtained Cronbach’s α for the intrapersonal resource loss items at each time wave was .81, .86, .89, and .90 sequentially. The Cronbach’s α for the interpersonal resource loss items across sequential time waves was .76, .77, .85, and .81.

PTSD Symptom Scale—Interview Format (PSS-I; Foa, Riggs, Dancu, Rothbaum, 1993)

The PSS-I is a 17-item measure that assesses participants’ PTSD symptom levels across re-experiencing, avoidance/numbing, and hyperarousal symptom clusters. Participants are instructed to answer the extent to which they have been distressed by each symptom in the past month, as a result of exposure to one or more incident of political violence, using a Likert-type scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (very much). Summing these items yields total scores in which higher scores reflect more severe posttraumatic stress symptoms. This measure has demonstrated adequate psychometric properties when used previously with Palestinian and Jewish samples (Hobfoll et al., 2011; Palmieri et al., 2008). Cronbach’s α for this variable at each sequential time wave was .86, .86, .89, and .90.

Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; Kroenke, Spitzer, Williams, 2001)

The PHQ-9 is a 9-item measure which assesses depressive symptom severity and has been demonstrated to be highly sensitive in identifying these symptoms. The PHQ-9 has been used in Israeli Palestinian populations (e.g., Hobfoll et al., 2010) and has been demonstrated to have good diagnostic accuracy and construct validity (Hobfoll et al., 2011). Participants are asked the extent to which they have experienced each symptom during the previous two weeks on a Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Sample items include “little interest or pleasure in doing things,” “feeling tired or having little energy,” and “feeling bad about yourself – or that you are a failure or have let yourself or your family down.” At each sequential time point, Cronbach’s α for this variable was .85, .88, .90, and .91.

Data Analysis

Zero-order correlations among demographic and primary study variables were computed to assess for bivariate relationships (see Table 2). Additionally, we used t-tests to ascertain between-group sex and marital status differences on these variables (see Table 1). Based on the data obtained from the bivariate correlation analyses, several demographic variables (i.e., age, education level, income, and sex) were included in the proposed model as covariates as they were found to be significantly related to key study variables. We also included marital status as control variable given it was a predictor of attrition in the sample. However, when tested in the structural equation model, marital status was not significantly related to any variable of interest and was thus removed from the final analyses presented here. As PTSD symptoms and exposure to political violence were major variables of interest, the significant differences on these variables between the attrition sample and the study participants in baseline scores will be considered in our discussion.

Table 2.

Correlations (Pearson r) among Demographic Variables and Primary Study Variables

|

Sex

(female) |

Age | Education | Income |

Marital Status

(married) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 Exposure | −.206* | −.032 | −.066□ | −.058 | −.028 |

| T1 Intraloss | −.039 | .048 | −.111* | −.086+ | .012 |

| T1 Interloss | −.061□ | .104* | −.099+ | −.036 | .049 |

| T1 PTSD | .069□ | .102+ | −.092+ | −.085+ | .020 |

| T1 Depression | .053 | .078+ | −.093+ | −.063□ | −.004 |

| T2 Intraloss | .016 | .033 | −.091+ | −.071□ | −.012 |

| T2 Interloss | .035 | .032 | −.070□ | −.069□ | −.035 |

| T2 PTSD | .122+ | .106+ | −.116+ | −.084□ | .038 |

| T2 Depression | .137+ | .081□ | −.108+ | −.071□ | −.006 |

| T3 Intraloss | −.048 | .072□ | −.121+ | −.061 | .004 |

| T3 Interloss | .009 | .076□ | −.119+ | −.099+ | −.007 |

| T3 PTSD | .072□ | .121+ | −.151+ | −.062 | −.020 |

| T3 Depression | .102+ | .164+ | −.131+ | −.068 | .056 |

| T4 Intraloss | −.050 | .061 | −.130+ | −.092□ | .027 |

| T4 Interloss | −.046 | .078□ | −.153+ | −.058 | .000 |

| T4 PTSD | .076□ | .132+ | −.168+ | −.108+ | −.011 |

| T4 Depression | .112+ | .158+ | −.166+ | −.103+ | .019 |

Note. Exposure = Exposure to Political Violence. Intraloss = intrapersonal resource loss. Interloss = interpersonal resource loss. T1 = baseline interview, (N = 1196). T2 = 6-month follow-up, (N = 889). T3 = 12-month follow-up, (N = 797). T4 = 18-month follow-up, (N = 752).

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

The full structural model was tested by including the baseline measures of exposure to traumatic events, sex, age, level of education, and income as manifest predictors of psychological distress and resource loss (measured at all four time waves). Resource loss was modeled as a latent variable which was measured by two observed variables: interpersonal and intrapersonal resource loss. Psychological distress was also represented as a latent variable measured by two observed variables: PTSD and depression scores. As each manifest indicator was measured at four time waves, the error terms for each variable (e.g., the error terms for PTSD symptom levels at each of the four waves) were freely estimated to aid in model identification and account for shared measurement error. Model goodness of fit was assessed using the residual mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA), with values below .08 and a lower bound of the 95% confidence interval (CI) less than .05, indicating excellent fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1993) and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI; Bentler, 1990), with values greater than .95 indicating excellent fit. Data were analyzed in the AMOS 18 program and missing data were handled via full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation (Enders, 2006). Inspection of skew and kurtosis statistics as well as normal and detrended Q-Q plots revealed that all study variables were univariate normally distributed (Kline, 2005; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). Due to large sample size (well over N = 1,000) and the use of bootstrapping procedures in the FIML estimation, multivariate normality is assumed (Byrne, 2010; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). The full correlation matrix for all study variables is available as supplemental online content via the journal’s website..

Results

Zero-Order Correlations among Study Variables

Several significant correlations emerged between the demographic variables of age, education, and income and several of the study variables of interest at the first time wave. As can be seen in Table 2, age was positively correlated with interpersonal resource loss (r = .10, p < .001), PTSD symptoms (r = .10, p = .001), and depression symptoms (r = .08, p = .007); education level was negatively correlated with all study variables (see Table 2 for the strength of these correlations); and income was negatively correlated with intrapersonal resource loss (r = − .09, p = .004), PTSD symptoms (r = −.09, p = .005), and depression symptoms (r = −.06, p = .033). Additionally, differences emerged between Palestinian men and women on several of the key variables of interest. Men reported exposure to more instances of political violence (M = 1.72, SD = 1.27) than did women, (M = 1.22, SD = 1.09, t(1150) = 7.14, p <.001). Despite this, women reported higher levels of PTSD symptoms (M = 22.20, SD = 9.23) than did men (M = 20.91, SD = 9.58, t(1145) = −2.33, p = .02). Further, men reported higher levels of interpersonal resource loss (M = 3.02, SD = 2.94) than their female counterparts (M = 2.68, SD = 2.67, t(1173) = 2.08, p = .038). Table 2 also includes correlations between the demographic variables and the study variables at the second through fourth time waves as well.

SEM Analyses to Assess Transactional Relationships among Distress and Resource Loss

First, we evaluated the hypothesized measurement model (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988) using all variables displayed in Figure 1, as well as the demographic variables of sex, age, education level, and income. This model included five observed variables (representing the four demographic variables and the exposure to political violence scale taken at the first time wave) and eight latent variables (indicated by psychological distress and resource loss, each measured at all four time waves). All variables, observed and latent, were allowed to freely intercorrelate for this measurement model to assess overall model fit as well as to estimate factor loadings of the indicators on the latent variables. The standardized factor loadings for PTSD symptoms on psychological distress at each time wave were .78, .83, .79, and .78, sequentially. The standardized factor loadings for depression symptoms on psychological distress at each time wave were .85, .83, .82, and .86, sequentially. The standardized factor loadings for interpersonal loss on resource loss at each time wave were .80, .82, .84, and .88, sequentially. Finally, the standardized factor loadings for intrapersonal loss on resource loss at each time wave were .92, .91, .94, and .94, sequentially. These loadings suggest that the latent variables are adequately estimated and the model fit indices suggest good fit to the data, χ2 (116, N = 1196) = 492.09, CFI = .96, RMSEA = .05, 90% CI = .05 - .06.

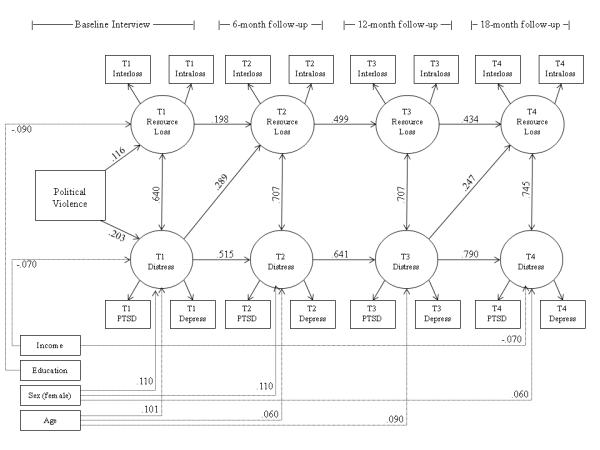

Next we tested the hypothesized structural model to assess cross-lagged, transactional effects across four time waves (see Figure 1). This preliminary model also fit the data well, χ2 (121, N = 1196) = 278.59, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .03, 90% CI = .03 - .04. Among demographic variables, being female significantly predicted greater psychological distress at baseline (β = .11, p < .001), 6-month follow up (β = .11, p < .001), and 18-month follow up (β = .06, p = .027); older age significantly predicted greater psychological distress at baseline (β = .10, p = .001), 6-month follow up (β = .06, p = .030), and 12-month follow up (β = .09, p = .011); lower education level significantly predicted greater resource loss at baseline (β = −.09, p = .008); and lower income significantly predicted greater psychological distress at baseline (β = −.07, p = .044) and at 18-month follow up (β = −.07, p = .036). Consistent with our first hypothesis, initial levels of exposure to political violence significantly predicted both baseline levels of resource loss (β = .12, p < .001) and psychological distress (β = .20, p < .001). All autoregressive pathways for the repeated assessments of both resource loss and psychological distress were significant. Additionally, all covariances between resource loss and psychological distress within each time wave were significant. To test our second hypothesis, that resource loss would predict subsequent psychological distress which would, in turn, predict subsequent resource loss, we examined cross-lagged path coefficients. Of the cross-lagged paths, psychological distress at baseline significantly predicted resource loss at the 6-month follow up (β = .29, p < .001) and psychological distress at 12 months significantly predicted resource loss at the 18-month follow up (β = .25, p < .001) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Cross-Lagged Structural Model of Transactional Relationships among Resource Loss and Psychological Distress. Interloss = interpersonal resource loss, Intraloss = intrapersonal resource loss, Distress = psychological distress, Depress = depression. Dashed lines denote covariates. Factor loadings and nonsignificant paths have been omitted for clarity.

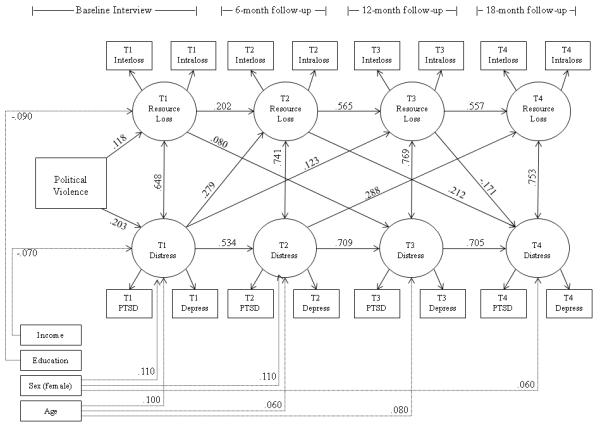

Finally, to expand upon our second hypothesis and to further explicate transactional relationships among these variables, we specified an additional, post hoc, model that included long-lagged effects (i.e., wave 1 latent variables predicting directly to waves 3 and 4, wave 2 latent variables directly predicting to wave 4) in addition to the cross-lagged pathways tested above. This final model demonstrated an improved fit to the underlying data structure, χ2 (115, N = 1196) = 237.93, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .03, 90% CI = .03 - .04. Because these are nested models, the likelihood ratio difference test reveals that adding long-lagged pathways significantly improved model fit, χ2 (6) = 40.66, p < .001. Demographic variables predicted to baseline resource loss and psychological distress in a nearly identical pattern to that which was obtained in the previous model. Being female significantly predicted greater psychological distress at baseline (β = .11, p = .001), 6-month follow up (β = .11, p < .001), and 18-month follow up (β = .06, p = .038); older age significantly predicted greater psychological distress at baseline (β = .10, p = .001), 6-month follow up (β = .06, p = .030), and 12-month follow up (β = .08, p = .020); lower education level significantly predicted greater resource loss at baseline (β = −.09); and lower income significantly predicted greater psychological distress at baseline (β = − .07). Significant pathways from political violence exposure to both resource loss and psychological distress, autoregressive pathways, and covariances are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Cross-Lagged Structural Model of Transactional Relationships among Resource Loss and Psychological Distress including Long-Lagged Delayed Effects. Interloss = interpersonal resource loss, Intraloss = intrapersonal resource loss, Distress = psychological distress, Depress = depression. Dashed lines denote covariates. Factor loadings and nonsignificant paths have been omitted for clarity.

When including long-lagged delayed effects, the pathway from psychological distress at the 12-month follow up predicting to resource loss at the 18-month follow up became nonsignificant while a significant negative cross-lagged relationship emerged between resource loss at 12 months predicting psychological distress at 18 months (β = −.17, p = .010). Four of the added long-lagged pathways were significant: psychological distress at baseline significantly predicted resource loss at the 12-month follow up (β = .12, p = .004), psychological distress at six months significantly predicted resource loss at the 18-month follow up (β = .28, p < .001), resource loss at baseline significantly predicted psychological distress at the 12-month follow up (β = .08, p = .024), and resource loss at six months significantly predicted psychological distress at the 18-month follow up (β = .21, p < .001) (see Figure 3).

Discussion

The present study provides strong empirical support for the construct of loss spirals in a highly traumatized Palestinian population. In our final models, across four time waves, psychosocial resource loss and psychological distress predicted each other over time. Specifically, in the cross-lagged model, distress is a stronger predictor of resource loss rather than resource loss predicting distress. However, when long-lagged paths are included in the model, psychosocial resource loss is the stronger predictor of distress. This suggests that over short time intervals (6 months in this case), psychological distress is the instigating variable in the loss spiral, but over longer time intervals (12 months) resource loss leads the loss spiral. Although the long-lagged effects are not as strong as the cross-lagged effects, they provide support for the idea that some transactional effects may take longer to manifest.

The exception to this was a negative relationship between resource loss at 12 months predicting psychological distress at 18 months when long-lagged delays were considered. This unexpected finding may be due to the re-portioning of variance when delayed effects were considered in the less constrained model. The additional significant pathway from baseline distress to resource loss at 12 months likely redistributed the variance in the 12-month resource loss variable which could have revealed the unexpected negative pathway. Further, the significant long-lagged effect between resource loss at six months to psychological distress at the final assessment could have also redistributed the variance in psychological distress at 18 months. Another potential explanation for this finding may be that sub-groups, or latent classes, of participants may exist that are differentially classified by this spiral. Multigroup analyses, such as latent growth modeling, may help determine if different groups exist as well as their trajectories through the spiral. However, as this is the first empirical investigation of the loss spiral corollary of COR theory, it is also possible that this pathway represents a part of the loss spiral not yet fully explained. Further research with additional time waves may shed more light on this unexpected pathway.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several notable strengths. First, although a substantial body of research has documented the relationships among trauma, PTSD, depression, and resource loss, transactional patterns have seldom been examined in mass casualty settings. Thus, this is the first empirical examination of the loss spiral effect, that trauma leads to both resource loss and psychological distress, both of which make the other worse over time.

Limitations of this study include the specificity of the population. Palestinians living in Israel have undergone specific kinds and chronicity of stressors and further research with other populations may yield differing manifestations of the loss spiral phenomenon. Although COR theory would suggest that the loss spiral occurs more generally following trauma, this remains an empirical question. Relatedly, exposure to violence was assessed only in the year prior to the study and thus was not subsequently included as a time-varying covariate. Exposure to violence can be assessed and quantified over time and future research is needed to further elucidate the specific nature of the impact of violence on the loss spiral at various time points. Also, the current study used 6-, 12-, and 18- month follow-up times and it remains unclear if this effect would continue across a longer timeframe. Given that a potential loss spiral reversal was discovered in the fourth and final time wave of this study, continued longitudinal assessment may demonstrate nuances of maintenance or stability of this change over time. It is also important to acknowledge that the measurement of PTSD and depression symptoms in this study were not of clinical diagnoses, but rather symptom intensity. This line of research would be further bolstered by including information regarding probable PTSD and depression diagnoses.

As is common in longitudinal designs, attrition may have impacted the findings in this study, as 444 participants dropped out during the 18-month span of this study. Non-completers had higher income, were less likely to be married, had less exposure to political violence, and lower levels of baseline PTSD symptoms when compared to participants who remained in the study. Although reasons for attrition are not known, it appears that the non-completers may have had greater resources and were less impacted by traumatic events (e.g., higher income, less exposure to violence, lower PTSD levels) than those who remained in the study. This raises an important question of whether the results of this study would generalize to a psychologically healthier population. Future research comparing individuals who were differentially affected by or exposed to trauma, as in multigroup designs, may prove fruitful in elucidating the nature of the loss spiral.

Clinical Implications and Conclusions

Future research examining the nature of loss spirals may move in two directions. First, the current study chose standard 6-month follow-up time points. A closer examination of more frequent time points using, for example, a daily diary method would further explicate our understanding of the time course of this effect. Second, studies tracking participants for longer follow-up would be helpful in understanding the longer term reciprocal relationships between psychological distress and psychosocial resource loss, including when recovery begins and if it is maintained. Multiple additional follow up interviews could also detect potential recovery spirals and yield information about the processes of healing and rebuilding after major and widespread trauma. Finally, these findings can help inform early interventions, such as resource enhancement strategies, aimed at stopping the loss spiral and preventing trauma survivors from reaching high levels of distress.

The existence of a loss spiral following traumatic and mass casualty events also has important clinical implications. Given that transactional relationships between resource loss and psychological distress can become increasingly deleterious over time, increased attention to early identification of individuals with symptoms of depression and PTSD will be crucial to early intervention. COR theory predicts, and the current study supports, that resource loss following traumatic events occurs quickly and cumulatively. As such, halting or reversing the loss spiral early in the cycle should be a focus of those providing care in environments with high rates of mass casualty events.

Our findings provide empirical support for the construct of loss spirals, a key corollary of Conservation of Resources Theory. The models described in this paper suggest a negative feedback loop following the experience of trauma. That is, the impact of trauma causes psychological distress in the form of depression and PTSD symptoms in addition to interpersonal and intrapersonal resource loss. Psychological distress and resource loss then feedback on each other resulting in a loss spiral as these variables predict each other over both shorter (6-month) and longer (12-month) time intervals. Although prior studies demonstrate significant correlations between resource loss and psychological distress (e.g. Canetti et al., 2010; Hobfoll et al., 2010), this is the first empirical evidence demonstrating support for the specific loss spiral component of COR theory. As such, it adds new and unique information to the body of literature supporting both a COR and appraisal theory understanding of the impact of trauma.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was made possible in part by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (RO1MH073687) to the last author.

References

- Abdeen Z, Qasrawi R, Nabil S, Shaheen M. Psychological reactions to Israeli occupation: Findings from the national study of school-based screening in Palestine. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2008;32:290–297. doi: 10.1177/0165025408092220. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JC, Gerbing DW. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;103:411–423. [Google Scholar]

- Benight CC, Ironson G, Klebe K, Carver CS, Wynings C, Burnett K, Schneiderman N. Conservation of resources and coping self-efficacy predicting distress following a natural disaster: A causal model analysis where the environment meets the mind. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping. 1999;12:107–126. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleich A, Gelkopf M, Solomon Z. Exposure to terrorism, stress-related mental health symptoms, and coping behaviors among a nationally representative sample in Israel. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290:612–620. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.5.612. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.5.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Galea S, Bucciarelli A, Vlahov D. What predicts psychological resilience after disaster? The role of demographics, resources, and life stress. Journal of Clinical and Consulting Psychology. 2007;75:671–682. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.671. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- B’Tselem [Retrieved January 04, 2010];Intifada fatalities. 2010 from http://www.btselem.org/english/statistics/Casualties.asp.

- Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. 2nd Ed Routledge; New York, NY: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Canetti D, Galea S, Hall BJ, Johnson RJ, Palmieri P, Hobfoll SE. Exposure to prolonged socio-political conflict and the risk of PTSD and depression among Palestinians. Psychiatry. 2010;73:219–231. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2010.73.3.219. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2010.73.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. Analyzing structural equation models with missing data. In: Hancock GR, Mueller RO, editors. Structural Equation Modeling: A Second Course. Information Age Publishing; Greenwich, CT: 2006. pp. 313–342. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Riggs DS, Dancu CV, Rothbaum BO. Reliability and validity of a brief instrument for assessing post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1993;6:459–473. doi: 10.1007/BF00974317. [Google Scholar]

- Giacaman R, Shannon HS, Saab H, Arya N, Boyce W. Individual and collective exposure to political violence: Palestinian adolescents coping with conflict. European Journal of Public Health. 2007;17:361–368. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl260. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE. Stress, culture, and community: The psychology and philosophy of stress. Plenum Press; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology. 2001;50:337–370. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE, Canetti D, Hall BJ, Brom D, Palmieri PA, Johnson RJ, Galea S. Are community studies of psychological trauma’s impact accurate? A study among Jews and Palestinians. Psychological Assessment. 2011 doi: 10.1037/a0022817. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1037/a0022817Hobfoll. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE, Hall BJ, Canetti D. Political violence, psychological distress, and perceived health: A longitudinal investigation in the Palestinian Authority. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2010 doi: 10.1037/a0018743. doi: 10.1037/a0018743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE, Lilly RS. Resource conservation as a strategy for community psychology. Journal of Community Psychology. 1993;21:128–148. doi: 10.1002/1520-6629(199304)21:2<128::AID-JCOP2290210206>3.0.CO;2-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE, Palmieri PA, Johnson RJ, Canetti-Nisim D, Hall BJ, Galea S. Trajectories of resilience, resistance and distress during ongoing terrorism: The case of Jews and Arabs in Israel. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:138–148. doi: 10.1037/a0014360. doi: 10.1037/a0014360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DM, Palmieri PA, Jackson AP, Hobfoll SE. Emotional numbing weakens abused inner-city women’s resiliency resources. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2007;20:197–206. doi: 10.1002/jts.20201. doi: 10.1002/jts.20201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaniasty K, Norris FH. A test of the social support deterioration model in the context of natural disaster. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;64(3):395–408. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.64.3.395. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.64.3.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2nd Ed The Guilford Press; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, DeLongis A, Folkman S, Gruen R. Stress and adaptational outcomes: The problem of confounded measures. American Psychologist. 1985;40:770–779. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.40.7.770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer; New York: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri PA, Canetti-Nisim D, Galea S, Johnson RJ, Hobfoll SE. The psychological impact of the Israel-Hezbollah War on Jews and Arabs in Israel: The impact of risk and resilience factors. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67:1208–1216. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.06.030. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palestinian National Authority. Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics Palestine in figures, 2008. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.paltrade.org/en/about-palestine/Palestine-in-Figures-2008.pdf.

- PCHR [Retrieved January 04, 2010];Palestinian Centre for Human Rights. Statistics related to Al Aqsa Intifada: 29 September, 2000- updated 20 December, 2008. 2010 from http://www.pchrgaza.org/alaqsaintifada.html.

- Shalev AY, Freedman S. PTSD Following terrorist attacks: A prospective evaluation. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1188–1191. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1188. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. 5th Ed Pearson Education, Inc; Boston, MA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.