Abstract

This study assessed how problem video game playing (PVP) varies with game type, or “genre,” among adult video gamers. Participants (n=3,380) were adults (18+) who reported playing video games for 1 hour or more during the past week and completed a nationally representative online survey. The survey asked about characteristics of video game use, including titles played in the past year and patterns of (problematic) use. Participants self-reported the extent to which characteristics of PVP (e.g., playing longer than intended) described their game play. Five percent of our sample reported moderate to extreme problems. PVP was concentrated among persons who reported playing first-person shooter, action adventure, role-playing, and gambling games most during the past year. The identification of a subset of game types most associated with problem use suggests new directions for research into the specific design elements and reward mechanics of “addictive” video games and those populations at greatest risk of PVP with the ultimate goal of better understanding, preventing, and treating this contemporary mental health problem.

Introduction

The topic of video game “addiction” has recently become the focus of media attention and the subject of an important public health debate.1 Individual stories of sensational deaths associated with video games appear to be best attributable to mental illness and media hyperbole and not the games themselves.2–5 However, empirical evidence for a genuine and pervasive “problem video game play” disorder (hereafter PVP) is growing. Gentile found that, among a nationally representative sample of youth age 8–18, 88 percent played video games and 8 percent exhibited pathological use.6 Desai et al.'s recent study of video gaming among U.S. high-school students found that nearly 5 percent reported all three indicators of impulse-control disorder studied: family concern, cutting back, and an irresistible urge to play.7 In a longitudinal study in Singapore, Gentile et al. found both an incidence rate among adolescents comparable to other studies8,9 and that pathology tended to persist over time.10

Research has established that PVP is population dependent while also raising questions about other, less studied covariates of PVP. A recent functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI)-based study demonstrated significant differences between mesocorticolimbic (reward center) activation in men and women playing the same video game.11 The authors implicate probable sex differences in brain functioning related to the neural processes surrounding reward. Other research establishes basic gendered differences in game play motivations,12,13 which may lead to important gendered differences in genre preference. Men are more likely to exhibit PVP, but are also more regular game players, suggesting that there may be a mechanism involving both biological and social gender differences.14,15

Preliminary research strongly suggests that some types of games are more likely to be associated with PVP than others due to features of game design. Loftus and Loftus observed more than 25 years ago that video games are designed around operant conditioning and behavioral reward schedules akin to those that can make gambling problematic.16,17 More recently, neuroscientific research has demonstrated that video game rewards—now understood to encompass everything from scores and achievements18 to virtual objects and clothing19—stimulate dopamine neurotransmission,20 the same process implicated in many addictive drug rewards and related neurochemical dysregulation.21 One recent Korean study found that gamers who preferred Role-Playing Games scored highest on an internet addiction metric.22

The contemporary game genre that has been most widely criticized for its PVP potential is the Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Game (MMORPG). MMORPGs have been hailed as a complex new sociocultural and economic phenomenon,23–25 although critics note that MMORPGs use “exploitative” operant conditioning design, which can more readily predispose players to PVP.26,27 An fMRI-based study examining cue-reactivity in World of Warcraft players found that game cravings in MMORPG “addicts” highly resembled drug dependent cravings.28 Another study found that MMORPG players were spending, on average, 25 hours per week and that 9 percent reported spending 40+ hours per week on one MMORPG title.29 In an experiment assigning one of four game types to a sample of 100 college students, those assigned to the MMORPG group reported significantly more hours played, worse overall health and sleep quality, greater interest in continued play, and greater interference with socializing and schoolwork.30 These studies highlight a number of design elements predisposing MMORPG players to PVP, including (1) the never-ending nature of the games; (2) the presence of enticing in-game items (e.g., swords, or blueprints/recipes to make one's own gear or magic spells) that “drop” from slain enemies only extremely rarely; (3) the social organization of in-game “guilds” around daily repetition of time-consuming activities; and (4) the paid membership that encourages getting the most from one's dollar.

Despite these insights, there has been no systematic ecological analysis of the variation in PVP across genres. The present study fills this important gap in research while also supplementing the literature. Petry noted that extant research into PVP has focused almost exclusively on children and adolescents to the detriment of our understanding of the persistence and prevalence of PVP in adulthood.31 This study addresses the knowledge gap. Additionally, it examines the extent to which PVP varies with stakes in conventional behavior—including education, employment, and marriage—which may serve as protective factors against PVP. This research explores the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Some video game genres are more likely to be associated with PVP than others.

Hypothesis 2: Men are more likely to experience PVP, although the effect may be mediated by gendered genre preference.

Hypothesis 3: Persons with stakes in conventional behavior (education, work, a partner) will be less likely to have PVP. Similarly, older persons with other potential stakes in conventionality may be less likely to have PVP than 18–29 year-olds.

Methods

Participants and recruitment

In 2010, Knowledge Networks, an online research service provider, was contracted to survey nationwide video game playing among adults. Panel members were recruited using probability-based random-digit dialing and address-based sampling methods. Households were provided with Internet access and computers where required. To generate the sample of adult video gamers, 15,642 e-mails were sent to panelists over 18 years of age, and 9,215 (59 percent) completed a brief screener instrument. Those who reported occasional or regular video game play were asked to report hours spent playing video and/or computer games during the past week. Those reporting one or more hours (n=3,380, or 37 percent) were eligible for the roughly 10 minute survey.

The research protocol was approved by the authors' IRBs. The screener and the survey were administered in English and Spanish. Informed consent was established. After completion, participants received “points” toward cash and other incentives offered by Knowledge Networks. Knowledge Networks prepared the data's poststratification weights. All calculations presented here employed these sample weights to obtain unbiased nationally representative estimates for the U.S. population aged 18 and above.

Sample demographics are presented in the last column of Table 1. Participants ranged in age from 18 to above 60. Women were well represented (41 percent). Blacks (10 percent) and Hispanics (12 percent) had a reasonably representative inclusion. Subjects had substantial stakes in social conventionality: most had graduated high school (89 percent), the majority were working (58 percent), most were member of households earning more than $30,000 per year (69 percent), and nearly half were married (45 percent).

Table 1.

Variation in Demographic Characteristics by Video Gaming Genre

| |

MMO RPG |

Other RPG |

Action adventure |

First-person shooter |

Other shooter |

Sports general |

Sports other |

Rhythm |

Driving |

Plat-former |

Real time strategy |

Other strategy |

Puzzle |

Board and card games |

Gam-bling |

Other |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Most common title/series | World of Warcraft | Fallout 3 | Grand Theft Auto | Call of Duty | Gears of War | Wii Fit/Sports | Madden NFL | Guitar Hero | Super Mario Kart | Super Mario Brothers | Starcraft | Farmville | Bejew-eled | Solitaire | Poker | Pac-Man | Total/mean |

| n (unweighted) | 96 | 114 | 130 | 263 | 31 | 180 | 197 | 62 | 81 | 121 | 60 | 110 | 317 | 499 | 108 | 283 | 2,652 |

| Percentage of sample (weighted) | 4 | 5 | 6 | 12 | 1 | 6 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 10 | 14 | 3 | 11 | 100 |

| Age | |||||||||||||||||

| 18–20a | 10 | 7 | 18 | 19 | 24 | 2 | 13 | 14 | 12 | 2 | 15 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 8 |

| 21–29a | 45 | 47 | 34 | 46 | 12 | 25 | 30 | 28 | 34 | 50 | 30 | 18 | 12 | 3 | 7 | 27 | 27 |

| 30–39a | 24 | 24 | 19 | 17 | 20 | 29 | 27 | 28 | 22 | 25 | 20 | 18 | 18 | 5 | 13 | 21 | 19 |

| 40–59a | 20 | 19 | 26 | 17 | 41 | 38 | 25 | 31 | 31 | 17 | 32 | 50 | 45 | 40 | 50 | 36 | 32 |

| 60+a | 1 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 12 | 23 | 52 | 30 | 10 | 14 |

| Femalea | 23 | 32 | 25 | 14 | 16 | 57 | 15 | 57 | 34 | 63 | 11 | 50 | 73 | 53 | 40 | 53 | 41 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||||||||||

| White (non-Hisp)a | 82 | 83 | 55 | 69 | 78 | 72 | 65 | 78 | 67 | 55 | 79 | 84 | 73 | 79 | 64 | 65 | 71 |

| Black (non-Hisp)a | 1 | 4 | 16 | 8 | 6 | 10 | 20 | 4 | 9 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 10 | 8 | 21 | 15 | 10 |

| Hispanica | 3 | 7 | 16 | 17 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 19 | 34 | 13 | 6 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 13 | 13 |

| Otherb | 14 | 6 | 13 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Education | |||||||||||||||||

| No H.S. degreea | 12 | 4 | 11 | 12 | 7 | 8 | 12 | 10 | 16 | 17 | 6 | 7 | 12 | 7 | 23 | 14 | 11 |

| H.S. degreeb | 19 | 24 | 35 | 31 | 33 | 29 | 37 | 32 | 27 | 33 | 20 | 35 | 33 | 29 | 37 | 34 | 31 |

| Some collegea | 36 | 49 | 29 | 36 | 49 | 25 | 30 | 31 | 39 | 23 | 30 | 35 | 26 | 34 | 23 | 30 | 32 |

| B.S. degreea | 32 | 23 | 24 | 20 | 11 | 38 | 20 | 27 | 18 | 27 | 44 | 23 | 28 | 30 | 17 | 22 | 25 |

| Employment | |||||||||||||||||

| Workinga | 60 | 55 | 52 | 66 | 48 | 77 | 64 | 61 | 59 | 65 | 70 | 59 | 58 | 43 | 39 | 58 | 58 |

| Unemployeda | 20 | 25 | 19 | 23 | 38 | 5 | 18 | 29 | 16 | 14 | 17 | 13 | 10 | 7 | 7 | 20 | 16 |

| Retireda | 20 | 20 | 29 | 12 | 14 | 18 | 18 | 9 | 26 | 21 | 13 | 28 | 32 | 50 | 54 | 23 | 26 |

| Household income | |||||||||||||||||

| <$30Ka | 24 | 32 | 33 | 25 | 41 | 15 | 37 | 30 | 38 | 33 | 25 | 29 | 32 | 29 | 45 | 40 | 31 |

| $30K–$59.9K | 33 | 29 | 35 | 35 | 20 | 36 | 26 | 28 | 21 | 41 | 26 | 35 | 34 | 33 | 30 | 30 | 32 |

| $60K+a | 43 | 39 | 32 | 40 | 39 | 49 | 36 | 42 | 41 | 27 | 49 | 36 | 34 | 38 | 24 | 30 | 37 |

| Marital status | |||||||||||||||||

| Marrieda | 34 | 40 | 33 | 40 | 30 | 66 | 33 | 53 | 50 | 56 | 39 | 54 | 49 | 53 | 43 | 43 | 45 |

| Cohabitinga | 11 | 10 | 16 | 11 | 11 | 7 | 17 | 11 | 12 | 16 | 4 | 11 | 8 | 7 | 11 | 13 | 11 |

| SepWidDiva | 11 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 7 | 9 | 8 | 2 | 10 | 14 | 16 | 26 | 24 | 25 | 14 | 14 |

| Singlea | 44 | 41 | 44 | 40 | 49 | 19 | 41 | 27 | 36 | 18 | 43 | 18 | 18 | 15 | 21 | 31 | 30 |

| Mean days of use in the past 30a | 15.1 | 8.8 | 9.5 | 11.2 | 9.2 | 7.5 | 10.0 | 5.8 | 5.8 | 6.8 | 12.1 | 15.7 | 15.1 | 16.6 | 15.6 | 10.4 | 11.6 |

| Mean hours per day of usea | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 3.7 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 4.9 | 2.9 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 2.7 | 2.8 |

| PVP ≥3a | 8 | 6 | 9 | 10 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 5 | 5 |

| PVP ≥3.5a | 5 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Analysis of variance test of variation across genre significant at the α=0.01 level.

ANOVA test of variation across genre significant at the α=0.05 level.

MMORPG, massively multiplayer online role-playing game.

Measures: video game genre

The 3,380 respondents were asked to identify the title of the video game they played most often during the past year. About 78.5 percent of responses were deemed valid. Many invalid responses identified a console (e.g., XBOX) or multiple games of different genres. Gamefaqs.com,32 a comprehensive archive, was used to sort the 2,652 valid video game titles into the following 15 mutually exclusive genres and one aggregate “other” category of less commonly reported genres:

• MMORPGs: players develop a character and interact collaboratively and competitively in a shared online world.

• Other role playing: Games rich in narrative, with usually a single player. Success depends on developing and managing characters with skills suited to achieving objectives.

• Action adventure: Games oriented toward combat and exploration, mostly in third-person perspective.

• First-person shooter (FPS): Kill-or-be-killed games from the player's eye view.

• Other shooter: Shooting games in third-person perspective.

• Sports general: Sports and workout games usually involving an interactive motion controller.

• Sports other: All other sports games, mostly realistic simulations of team sports.

• Rhythm: Music and dance games often involving a unique controller similar to a guitar or dance pad.

• Driving: Primarily racing games.

• Platformer: Games requiring precision movement and jumping.

• Real-time strategy: Strategic combat-oriented games with no wait between moves.

• Other strategy: Turn based (i.e., waiting on the player to act) and other forms of strategic simulation.

• Puzzle: Games involving matching, logic, deductive reasoning, and other puzzles.

• Board and card games: Simulations of primarily classic games without gambling.

• Gambling: Primarily simulations of Poker, Black Jack, and slot machine gambling.

• Other: All genres with fewer than 30 reported cases.

Measures: problem use of video games

Early research into PVP recognized similarities between problem video gamers and pathological gamblers—partly due to similarities between video arcades and casino games.33 Early measures of PVP were based on DSM- IV measures of pathological gambling.15,34 Since video gaming has increasingly moved to the home, the economically oriented items from earlier PVP scales have become obsolete.5 More recently, Salguero and Moran developed a hybrid metric based on measures of gambling and substance abuse and demonstrated the instrument's internal validity and reliability.35

This project modified the PVP instrument for fast application. A sample of 114 subjects (not included in this analysis) were asked all nine items of the original PVP scale. The five highest-loading items in a principal components analysis were selected as a shorter PVP scale. Participants reported a score of 1 (not at all true), 2 (somewhat true), 3 (moderately true), 4 (very true), or 5 (extremely true) for the following items:

• You spend an increasing amount of time playing video games.

• You usually play video games over a longer period than you intended.

• When you cannot play video games, you get restless or irritable.

• When you feel bad, for example, nervous, sad, or angry, or when you have problems, you play video games more often.

• In order to play video games you have skipped classes or work, or lied, or stolen, or had an argument or a fight with someone.

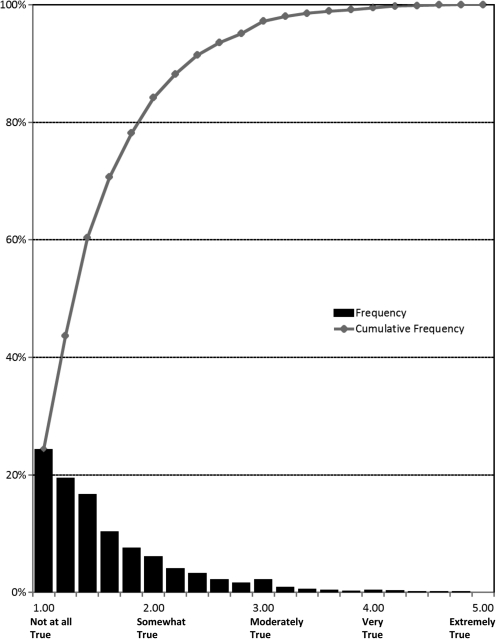

When applied to the full sample, the scale had good reliability (α=0.74). A higher mean score across these self-reported items indicates potentially greater levels of video-game-related problems. Absent clinical assessment, findings are suggestive but should not be interpreted as a diagnosis of PVP. Analysis of a histogram (Fig. 1 below) suggested the study could accurately distinguish characteristics associated with moderately or more severe symptoms (a score of 3 or more, hereafter PVP ≥3). This article also examines the distribution of those with more severe symptoms (PVP ≥3.5) across genres.

FIG. 1.

Variation in the Problem Video Game Index.

Analyses

Logistic regression identified variation in moderate or more severe problem use (PVP ≥3) associated with genre, demographics, and stakes in conventionality. Wald tests were used to measure the relative amount of variation explained by each variable, controlling for all other variables included, and also to test for statistical significance.

Results

Figure 1 presents the distribution of mean PVP scores. Most participants reported little evidence of PVP. Nearly one fourth (24 percent) reported a complete absence of PVP, answering “not at all true” on all five items. Ninety-five percent of the scores were below a 3 (“moderately true”). Although the different measures of problem or “addictive” gaming employed in this and other published studies prevent authoritative comparison, this strongly suggests that PVP is a less common concern among adults than within the adolescent populations conventionally studied.

Table 1 reports how demographics, usage, and PVP varied by genre. Board and card games had the highest mean number of days played in the past month, followed by other strategy, gambling, and MMORPGs. Real-time strategy games were used for the most hours on days played, followed by other shooter, FPS, other RPGs, and MMORPGs. Rhythm games were played for the fewest number of days in the past month and for the fewest hours on days played.

Extremely few puzzle, board and card, and other strategy gamers reported PVP ≥3, despite their relatively high reports of the number of days used in the past month. PVP among sports general and platformer audiences was also relatively rare. Contrastingly, action adventure, MMORPG, FPS, and gambling gamers all had a relatively high incidence of PVP ≥3. Incidence of PVP ≥3.5 was most highly concentrated among MMORPG and FPS players.

Age varied significantly players by genre. Modal age for MMORPG, RPG, FPS, and platformer title audiences was 21–29. For puzzle, other strategy and sports general games, modal age was 40–59. For board and card games, it was 60+. Among sports general, puzzle games, board/card games, and platformers, women were highly represented. Within sports other, role-playing games, shooter, and real-time strategy genres, men were disproportionately represented. Whites were highly represented among role-playing and strategy games; Blacks, among gambling and sports games; and Latinos, among platformers. The highest levels of education and income were found among players of sports general games and real-time strategy games, while the lowest were among gambling and platformer games. Retired persons were commonly gambling and board/card gamers. Married persons were well represented in most game genres, but single was the modal marital category for MMORPGs, other RPG, other shooter, sports other, action adventure, and real-time strategy games.

Multivariate analysis of PVP

Table 2 presents the multivariate analysis of the variation in PVP ≥3. The results affirmed Hypothesis 1. PVP ≥3 was most associated with FPS, action-adventure, MMORPG, and gambling. The odds of PVP ≥3 among these genres were generally twice that associated with other focal genres. Greater stakes in conventionality were associated with a substantially diminished risk of PVP ≥3. The prevalence was lower for those with greater education, employment, and a spouse. Having a cohabiting partner was associated with a greater risk of PVP ≥3 than being single. Notably, there was no statistically significant variation associated with demographic factors after controlling for genre and stakes in conventionality. This suggests that female, older, and minority gamers are equally likely to manifest PVP as their male, younger, and white counterparts when choosing the same genre.

Table 2.

Multivariate Analysis of Variation in Problem Video Game Playing

| Odds ratio (Wald Statistic) | |

|---|---|

| Genre | (26.3)a |

| MMO role-playingb | 1.0 |

| Other role-playing | 0.8 |

| Action-adventure | 1.1 |

| First-person shooter | 1.4 |

| Other shooter | 0.5 |

| Driving | 0.4 |

| Platformer | 0.3 |

| Puzzle | 0.4 |

| Board and card games | 0.3 |

| Gambling | 1.1 |

| Real-time strategy | 0.7 |

| Other strategy | 0.1 |

| Sports-general | 0.4 |

| Sports-other | 0.6 |

| Rhythm | 0.6 |

| Other | 0.6 |

| Education | (8.5)a |

| Less than high school | 1.5 |

| High school degreeb | 1.0 |

| Some college | 0.7 |

| Bachelor's degree or higher | 0.7 |

| Employment | (7.4)a |

| Workingb | 1.0 |

| Unemployed | 1.6 |

| Retired/disabled/other | 1.8 |

| Marital status | (11.1)a |

| Marriedb | 1.0 |

| Cohabiting | 2.6 |

| Separated/widowed/divorced | 1.7 |

| Never married | 1.8 |

| Base odds | 0.056:1=5 percent |

Gender, age, and race were included in the model; however, the variation associated with each of these variables was not statistically significant at the α=0.05 level.

Significant at α=0.05 level (but not 0.01) level.

Reference category.

Discussion

This ecological assessment of PVP among U.S. adults by genre contributes several valuable insights. Although PVP of moderate severity was limited to <5 percent of our participants, the central hypothesis that game type (or genre) plays an important role in PVP was affirmed. The greatest prevalence of PVP ≥3 was among FPS, action-adventure, MMORPG, and gambling gamers. Unsurprisingly, the MMORPG was strongly associated with higher degrees of PVP, as suggested in a range of published literature.17,22–25,27–30 It is also interesting that gambling video games were associated with PVP. Based on the titles entered by study participants alone, it was not possible to discriminate those playing gambling simulations from those gambling at online sites that allow actual wagers. Further research will be necessary before an understanding emerges about how virtual rewards in video games differ from monetary reinforcements. Recent sales figures for blockbuster series such as Call of Duty and Halo indicate a huge audience for the FPS genre in America; our findings suggest that a considerable subpopulation is experiencing at least moderate degrees of PVP. The action-adventure genre is noteworthy for containing some of the most controversial games ever published, such as the Grand Theft Auto series,36 as well as many less violent titles. Future research should elucidate the design elements specific to these genres (and/or the underlying psychosocial characteristics of their players) that explain players' increased risk of PVP. Perhaps the immersion potential of a first-person perspective, commonly combined with online competition,13 largely accounts for higher rates of PVP. For action-adventure games, a trend toward nonlinear “open-world” style environments in which extensive, time-consuming exploration is encouraged may create a context for more pervasive experiences of PVP. These interpretations are speculative at this point but suggest important avenues of exploration for future research.

Genre was a much more robust covariate of PVP than the demographic and background variables examined. Hoeft et al. found that the neural activity and arousal associated with video gaming varied systematically with gender.11 In our multivariate analysis, gender exhibited no effect on problem use after controlling for genre. Overall, the percentage of male gamers with PVP ≥3 (6 percent) was higher than for female gamers (4 percent). However, the regression parameter estimate associated with gender was not statistically significant. This suggests that gender-based differences in susceptibility to problem use6,7,10 may be mediated by gendered preference for genre. Similarly, race/ethnicity and age were not associated with PVP after controlling for genre and stakes in social conventionality.

Several findings were consistent with our third hypothesis: higher stakes in conventional behavior serve as a protective factor against PVP. Lacking a high-school diploma was identified as a risk factor for PVP, as was unemployment, retirement, and disability, likely due to the availability of time for gaming within these populations. Similarly, being married was protective relative to never having married or being separated, widowed, or divorced. Alternately, cohabitation was strongly associated with greater PVP for reasons not readily discerned. It is likely grounded in emergent sociocultural trends regarding marriage,37 for which cohabitation served here as a proxy variable. Without further, longitudinal research, however, reverse causation remains a strong possibility; persons who are prone to PVP may be less likely to complete high school, work steadily, or marry.

A major goal of research into PVP is to suggest important dimensions of future evidence-based prevention and rehabilitation therapies. Given the current state of the field and the need for contextually sensitive approaches to treating and identifying PVP, this study represents an important precedent establishing basic differences in problem use potential among multiple game genres available in today's marketplace.

Acknowledgments

These analyses were supported by grant R01-DA027761, “Video Games' Role in Developing Substance Use,” from the National Institute of Drug Abuse. The content is the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of National Development and Research Institutes, Adelphi University, the National Institute of Drug Abuse, or the National Institutes of Health. The authors would like to thank Peter Vazan for his helpful commentary on drafts of this article and Elizabeth McGinsky for her expert coding assistance and feedback on the article.

Disclosure Statement

There are no conflicts of interest to be reported for any of this article's authors.

References

- 1.Young K. Understanding online gaming addiction and treatment issues for adolescents. American Journal of Family Therapy. 2009;37:355–372. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tran M. The Guardian Friday. World News; South Korea: Mar. 2010. [Nov.2011 ]. Girl starved to death while parents raised virtual child in online game. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haines L. Online gamer murders rival clan member. The Register. Jan. 2008. www.theregister.co.uk/2008/01/17/gaming_murder/ [Nov.2011 ]. www.theregister.co.uk/2008/01/17/gaming_murder/

- 4.Kropko MR. Ohio teen convicted of killing mom over video game. Associated Press. Jan. 2009. www.msnbc.msn.com/id/28623160/ns/us_news-crime_and_courts/t/teen-convicted-killing-mom-over-video-game/ [Nov.2011 ]. www.msnbc.msn.com/id/28623160/ns/us_news-crime_and_courts/t/teen-convicted-killing-mom-over-video-game/

- 5.Wood RTA. Problems with the concept of video game “addiction”: some case study examples. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2008;6:169–178. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gentile DA. Pathological video-game use among youth ages 8 to 18. Psychological Science. 2009;20:594–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desai RA. Krishnan-Sarin S. Cavallo D. Potenza MN. Video-gaming among high school students: health correlates, gender differences, and problematic gaming. Pediatrics. 2010;126:1414–1424. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grüsser SM. Thalemann R. Griffiths MD. Excessive computer game playing: evidence for addiction and aggression? CyberPsychology & Behavior. 2007;10:290–292. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2006.9956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Porter G. Starcevic V. Berle D. Fenech P. Recognizing problem video game use. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;44:120–128. doi: 10.3109/00048670903279812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gentile DA. Choo H. Liau A, et al. Pathological video game use among youths: a two-year longitudinal study. Pediatrics. 2011;127:319–329. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoeft F. Watson CL. Kesler SR. Bettinger KE. Reiss AL. Gender differences in the mesocorticolimbic system during computer game-play. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2008;42:253–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lucas K. Sherry J. Sex differences in video game play. Communication Research. 2004;31:499. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olson CK. Children's motivations for video game play in the context of normal development. Review of General Psychology. 2010;14:180–187. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griffiths M. Hunt N. Dependence on computer games by adolescents. Psychological Reports. 1998;82:475. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1998.82.2.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fisher S. Identifying video game addiction in children and adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 1994;19:545–553. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blaszczynski A. Nower L. A pathways model of problem and pathological gambling. Addiction. 2002;97:487–499. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loftus GR. Loftus EF. Mind at play: the psychology of video games. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jakobsson M. The achievement machine: understanding Xbox 360 achievements in gaming practices. http://gamestudies.org/1101/articles/jakobsson. [Nov.2011 ];Game Studies. 2011 11 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore C. Hats of affect: a study of affect, achievements and hats in Team Fortress 2. Game Studies. 2011. http://gamestudies.org/1101/articles/moore. [Nov.2011 ]. p. 11.http://gamestudies.org/1101/articles/moore

- 20.Koepp MJ. Gunn RN. Lawrence AD, et al. Evidence for striatal dopamine release during a video game. Nature. 1998;393:266–268. doi: 10.1038/30498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Volkow N. Fowler J. Wang G. Swanson J. Telang F. Dopamine in drug abuse and addiction: results of imaging studies and treatment implications. Archives of Neurology. 2007;64:1575. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.11.1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee M. Ko Y. Song H, et al. Characteristics of internet use in relation to game genre in Korean adolescents. CyberPsychology & Behavior. 2007;10:278–285. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2006.9958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boellstorff T. Coming of age in Second Life: an anthropologist explores the virtually human. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor TL. Play between worlds: exploring online game culture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castronova E. Synthetic worlds: the business and culture of online games. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hill J. Ethical dilemmas: exploitative multiplayer worlds don't deserve to be called art. The Sydney Morning Herald. 2007 Sept. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Cleave R. Unplugged: my journey into the dark world of video game addiction. Deerfield Beach, FL: Health Communications, Inc.; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ko C. Liu G. Hsiao S, et al. Brain activities associated with gaming urge of online gaming addiction. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2009;43:739–747. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Griffiths MD. Davies M. Chappell D. Demographic factors and playing variables in online computer gaming. Cyberpsychology & Behavior. 2004;7:479–487. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2004.7.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smyth J. Beyond self-selection in video game play: an experimental examination of the consequences of massively multiplayer online role-playing game play. CyberPsychology & Behavior. 2007;10:717–721. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2007.9963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petry NM. Commentary on Van Rooij et al. (2011): ‘Gaming addiction’–a psychiatric disorder or not? Addiction. 2011;106:213–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.CBS Interactive, Inc. Video game cheats, reviews, FAQs, message boards, and more—GameFAQs. 2011. www.gamefaqs.com/ [Mar.2011 ]. www.gamefaqs.com/

- 33.Griffiths MD. Amusement machine playing in childhood and adolescence: a comparative analysis of video games and fruit machines. Journal of Adolescence. 1991;14:53–73. doi: 10.1016/0140-1971(91)90045-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tejeiro Salguero RA. La práctica de videojuegos en niños del Camo de Gibraltar [Video game use in the Campo de Gibraltar youth] Algeciras: Asociación JARCA; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tejeiro Salguero RA. Bersabé Moran RM. Measuring problem video game playing in adolescents. Addiction. 2002;97:1601–1606. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garrelts N. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co; 2006. The meaning and culture of Grand theft auto: critical essays. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cherlin AJ. The marriage-go-round: the state of marriage and the family in America today. 1st. New York: Alfred A. Knopf; 2009. [Google Scholar]