Abstract

Background and the purpose of the study

Candida species are the agents of local and systemic opportunistic infections and have become a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the last few decades. Azole resistance in Candida krusei (C. krusei) species appears to be the result of gene alterations in relation to the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway, as well as efflux pumps. The main objective of this study was to examine the RNA expression of ERG11 in C. krusei which had been identified to be resistance to azoles.

Methods

The ERG11 mRNA expression was investigated in four Iranian clinical isolates of C. krusei, which were resistant to fluconazole and itraconazole by a semiquantitative RT-PCR. Results: The mRNA expression levels were observed in all four isolates by this technique. Furthermore, it was found that ERG11 expression levels vary among four representative isolates of C. krusei. Although DNA sequencing revealed no significant genetic alteration in the ERG11 gene, one heterozygous polymorphism was observed in two isolates, but not in others. This polymorphism was found in the third base of codon 313 for Thr (ACT>ACC).

Major conclusion

Even though such a polymorphism creates a new Ear1 restriction site, no significant effect was found on the resistance of C. krusei to azoles. Results of this investigation are consistent with previous studies and may provide further evidence for the genetic heterogeneity and complexity of the ergosterol biosynthetic pathway or efflux pumps.

Keywords: Polymorphism, Drug resistance, Gene expression, RT-PCR

INTRODUCTION

Candida species (spp) are agents of local and systemic opportunistic infections worldwide and have been described as the fourth leading cause of nosocomial bloodstream infections (BSIs). Moreover, treatment failures and development of the drug resistance have frequently been reported (1). Although C. albicans is the most important cause of candidemia, an increasing number of infections due to non Candida albicans species such as C. glabrata and C. krusei have also been reported (2). On the basis of reports 95% of Candida BSIs are associated with C. albicans, C. parapsilosis, C. glabrata, and C. tropicalis species and 12–14 of other Candida spp are involved in 5% of BSIs (3–5). A slight increase of BSIs due to non-albicans species has been reported, and C. krusei accounts for 24% of all Candida nosocomial bloodstream infections. It is known that this species has a tendency to appear in a setting where fluconazole has been administered for prophylaxis (5). Colonization and infection with fluconazole-resistant Candida spp. has often been observed among high risk patients with hematological malignancies under the selective routine fluconazole prophylaxis (6, 7). C. krusei has been detected as an uncommon and potentially multi-drug resistant (MDR) pathogen. In vitro antifungal testing has shown a considerable reduction in susceptibility of C. krusei to fluconazole (2.9% sensitive) and amphotriecin B (8% of all isolates), and the emerging pathogenicity of this organism is of increasing public health concern (8). It has been demonstrated that multiple mechanisms are involved in azole resistance, including overexpression of several genes encoding efflux pumps such as CDR1, CDR2 and MDR1 (multi-drug resistance), which lead to reduced intracellular accumulation of fluconazole and overexpression of the ERG11 gene, coding for the sterol 14α-demethylase (9, 10).

Some studies have proposed reduction in susceptibility of sterol 14α-demethylase to fluconazole as major resistance mechanism in C. krusei (11–14). The present study was aimed to investigate the expression of ERG11 in four Iranian C. krusei isolates.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Fungal strains

Four fluconazole and itraconazole resistant C. krusei strains were included in the present study (Table 1). These strains were isolated from cancerous patients with oropharyngeal Candida infections during 2006–2008 and had been identified previously (15). The susceptibility testing of the isolates to fluconazole and itraconazole was performed according to the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards M27-A (NCCLS) by broth microdilution method (16). Susceptibility tests were carried out in RPMI 1640 medium (SigmaAldrich, USA) buffered to pH 7.0 with 0.165 M morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS). The MICs were defined as concentrations of the drug that reduced growth by 80% compared to that of organisms grown in the absence of the drug. NCCLS-recommended quality control (Candida krusei ATCC 6258) was included in each test run, and MICs were within the recommended range for each test. The isolates had been stored in glycerol/ water at −80°C until used. The inocula for each individual experiment were prepared from these stocks.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Candida krusei strains used in this study.

| Strain | Predisposing factor | Site of isolation | MICa (ng/ml) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FLCb | ITCc | |||

| C. krusei 2 | Carcinoma (lung) | Orophrynex | 64 | 1 |

| C. krusei 118 | Lymphoma | “ | 128 | 1 |

| C. krusei 124 | Lymphoma | “ | 64 | 2 |

| C. krusei 144 | Leukaemia | “ | 64 | 2 |

: Minimum Inhibitory Concentration

:Fluconazole

:Itraconazole

Total RNA and cDNA synthesis extraction

C. krusei cells were grown on Sabouraud dextrose agar at 37°C for 24 hrs. Two to three fresh colonies were transferred to yeast peptone dextrose (YPD) broth (yeast extract 1%, peptone 2%, dextrose 2%), (Suprapur, Merck, Germany) at the same temperature for 48 hrs.

Total RNA was isolated from exponential-phase of the YPD broth cultures using RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Quantification of RNA was performed by absorbance at 260 nm using a Spectrophotometer (Biophotometer). The mean RNA concentration and the mean ratio for OD260/280 were 421+6 ng/µl and 1.8+0.04, respectively. For cDNA synthesis, 10 µl of total RNA was heated in 80°C for 10 min followed by cooling on ice. The master mixture contained 4 µl of 5x reverse transcriptase (RT) buffer, 10 mM of each dNTP, 20 pmol/µl random primer, 20 U RNase inhibitor (Fermentas, Burlington Canada), 200 U of Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus (MMuLV) Reverse Transcriptase (Fermentas, Burlington Canada), and 1.5 µl of DEPC-treated water. The cDNA synthesis was performed under following conditions: 42°C for 60 min, 70°C for 10 min, and finally cooling to 4°C. The integrity of cDNA was checked using the house keeping gene 18sRNA primers (as shown in table 2) which amplify region 1433–1639 (GB. EU348783.1). Samples with similar cDNA quality through 18sRNA PCR were stored at -70°C for further investigation.

Table 2.

List of primers used in this study.

| Primer Name | Primer Sequences 5′→3′ | Accession Number | PCR Product Sizes (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Semi-Quantitative RT-PCR Primers | |||

| 18SCF | 5′-GACGGAGCCAGCGAGTATAA-3′ | GB.EU348783.1 | 206 |

| 18SCR | 5′-GGGCTCACTAAGCCATTCAA-3′ | ||

| ERG11F | 5′-AATGGGTGGTCAACATACTT-3′ | DQ903905 | 508 |

| ERG11R | 5′-TGGTGGTAGACATAGATGTATT-3′ | ||

| Sequencing Primers | |||

| ER11SF | 5′-GTTTACGGAAAACCTTAC-3′ | DQ903905 | 1218 |

| ER11SR | 5′-GGTACATCTATGTCTACCACCACCA-3′ | ||

PCR amplification of the ERG11 gene was conducted on samples using 1 µl of cDNA, specific forward and reverse primers corresponding to ERG11gene (Table 2), dNTP, MgCl, Taq DNA polymerase, and buffer (CinnaGen, Tehran, Iran). The thermocycling was performed using a Touch-Down amplification program on 2720 Thermal Cycler, ABI. The PCR condition was as the same as previously described (17).

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR was conducted by the reported method with minor modification (18, 19). Briefly, specific primers corresponding to ERG11 and 18s rRNA mRNA sequences were designed. Appropriate dilutions of the samples were determined for each cDNA to make sure that examined transcripts and 18sRNA (internal control) amplification was in the exponential phase of the reaction.

DNA sequencing

For mutation screening, genomic DNA was extracted from 5×107 cells using DNGPLUS kit (CinnaGen, Tehran, Iran). PCR amplification of whole ERG11 gene was carried out using specific primer pairs (Table 2). To detect any mutation, the PCR product was subjected to direct sequencing (Gen-Fanavaran, Tehran, Iran). Sequence data searches were performed in non-redundant nucleic and protein databases BLAST (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ BLAST).

RESULTS

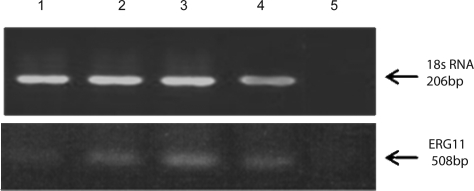

Four C. krusei isolates exhibited ERG11 mRNA overexpression at various levels. A semiquantitative RT-PCR was used to compare positive results of expression levels as: no expression (0), mild (1+), moderate (2+), high expression (3+) and the highest expression (+4) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

ERG11 mRNA expression.

RT-PCR products of ERG11 gene of clinical isolates of C. krusei, resistant to fluconazole and itraconazole on 1.8% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. Lanes 1(+1), 2 (+4), 3 (+3) and 4 (+2): indicate different levels of ERG11 mRNA expression (508bp); lane 5: negative control (water).18srRNA (206bp) was used as a positive control.

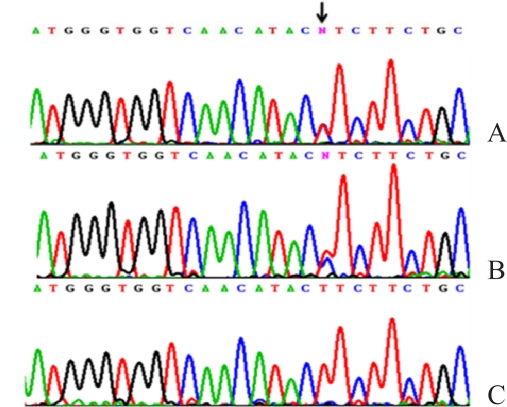

Direct DNA sequencing was carried out for investigation of the molecular bases of ERG11 overexpression. Amplified PCR products of the complete coding sequences of this gene from four C. krusei isolates were sequenced. The chromatogram of ERG11 DNA sequencing (Figures 2A, B) indicated a heterozygous base-substitution in two C. krusei isolates, in which a heterozygous change had occurred in the third base of codon 313 for Thr (DQ903905). Figure 2 C shows homozygous condition of the mentioned polymorphism. Although this genetic alteration (ACT>ACC) can not change the amino acid sequence of the ERG11 protein, it leads to the creation of an Ear1 restriction enzyme recognition site. Also, direct PCR sequencing of other samples revealed no mutation (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Mutation analysis of the ERG11 genomic DNA.

(A, B) A heterozygous polymorphism in codon 313 for Thr (ACT>ACC) in which T→C at position 939 of mRNA (DQ903905) was found in two samples. (C) A chromatogram from one of the samples indicates wild type homozygous condition.

DISCUSSION

Ergosterol biosynthesis is a complex metabolic pathway. So far, the involvement of several genes encoding enzymes in this pathway has been identified. It has been well documented that some of these metabolic steps are critical for cell viability. For instance, ERG11 deletions are lethal in S. cerevisiae (9), whereas no specific gene in C. krusei has been reported to exert significant effect. Previous studies have shown the role of ERG11 upregulation in fluconazole-resistant clinical isolates of Candida spp. (20). Several lines of evidence suggested that other genes of the sterol biosynthetic pathway (ERG3) and another pathway such as efflux pumps also play critical roles in the antifungal resistance of yeast (21–24). Moreover, some studies have shown involvement of efflux pumps in increasing the levels of resistance of C. krusei to azoles (25–30). In this study a semi-quantitative RT-PCR employing 18sRNA as an internal control was performed for detection of the levels of ERG11 expression in clinical isolates of C. krusei. All isolates revealed variations in ERG11 expression levels. To date, more than 20 genes have been found that are involved in azole resistance.

In general, ERG genes were found to be unregulated by either the reduction of a late product; or an accumulation of an early substrate or toxic sterol intermediates of the ergostrol biosynthetic pathway. It has been clearly demonstrated that several different inhibitors can affect different enzymes of this pathway which lead to upregulation of ERG genes in S. cerevisiae and Candida spp. Moreover, most previous studies have shown that the levels of ergosterol or other intermediate sterols which are formed in this pathway might be responsible for regulation of ERG expression in these species (20, 30). The exact molecular mechanism behind the upregulation of ERG11 gene in response to azoles and other antifungal drugs is not completely understood. Therefore, it was considered to investigate whether various amino acid substitutions or probable mutations, cause enhanced expression of ERG11 and changes in azole susceptibility (31). Our DNA sequence analysis of the ERG11 coding region displayed a heterozygous base substitution T→C (ACT>ACC) in two C. krusei isolates. However, this genetic alteration cannot lead to a change in the amino acid sequence of ERG11 protein which creates an Ear1 restriction enzyme recognition site. It has been well documented that protein- DNA interactions play a fundamental role in cell biology (32). Therefore, this polymorphism might play a critical role in the transcriptional regulation of genes which might be involved in the processes of ergosterol biosynthesis.

In addition, data of this study revealed that C. krusei is a diploid organism, which is in agreement with most recent findings which have identified different alleles for ERG11 gene in C. kruse strains (27).

CONCLUSION

The ERG11 overexpression is unlikely to be the cause of azole resistance in C. krusei isolates. A potential mechanism for azole resistance could be the level of promoter activity which is equivalent to the rate of ergosterol or sterol biosynthesis, as it has been confirmed in yeasts and human beings. In fact, it appears that stimulation of the ERG11 promoter has arisen in response to sterol deprivation or a reduced level of sterol resources. It is noteworthy that upregulation of ERG11 could be affected by its upstream (ERG9, ERG1, ERG7) or downstream genes (ERG3, ERG25). Additionally, genetic changes in the ERG11 promoter region may also modulate levels of the expression of genes that are involved in ergosterol biosynthesis. Other possibilities to explain ERG11 overexpression and azole resistance might be due to the growth conditions, carbon source and semi-anaerobic growth of fungal cells.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This reacerch has been supported by Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS) grant.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pfaller MA, Jones RN, Messer SA, Edmond MB, Wenzel RP. National surveillance of nosocomial blood stream infection due to species of candida other than Candida albicans: Frequency of occurrence and antifungal susceptibility in the scope program. Diagnostic microbiology and infectious disease. 1998;30:121–129. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(97)00240-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hajjeh RA, Sofair AN, Harrison LH, Lyon GM, Arthington-Skaggs BA, Mirza SA, Phelan M, Morgan J, Lee-Yang W, Ciblak MA. Incidence of bloodstream infections due to Candida species and in vitro susceptibilities of isolates collected from 1998 to 2000 in a population-based active surveillance program. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2004;42:1519–1527. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.4.1519-1527.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Rex JH, Pappas P.G, Hamill RJ, Larsen RA, Horowitz HW, Powderly WG, Hyslop N, Kauffman CA, Cleary J. Antifungal susceptibility survey of 2,000 bloodstream Candida isolates in the united states. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2003;47:3149–3154. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.10.3149-3154.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ. Twelve years of fluconazole in clinical practice: Global trends in species distribution and fluconazole susceptibility of bloodstream isolates of Candida . Clinical Microbiology & Infection. 2004;10:11–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1470-9465.2004.t01-1-00844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ, Messer SA, Boyken L, Hollis RJ, Jones RN. In vitro susceptibilities of rare Candida bloodstream isolavtes to ravuconazole and three comparative antifungal agents. Diagnostic Microbiology & Infectious Disease. 2004;48:101–105. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hsueh PR, Teng LJ, Ho SW, Luh K.T. Catheter-related sepsis due to Rhodotorula glutinis . Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2003;41:857–859. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.2.857-859.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wingard JR. Importance of Candida species other than C. albicans as pathogens in oncology patients. Clinical infectious diseases. 1995:115–125. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pappas PG, Rex J.H, Sobel JD, Filler SG, Dismukes WE, Walsh TJ, Edwards JE. Guidelines for treatment of candidiasis. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2003;38:161–189. doi: 10.1086/380796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kennedy MA, Barbuch R, Bard M. Transcriptional regulation of the squalene synthase gene (erg9) in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1445:110–122. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(99)00035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franz R, Kelly SL, Lamb DC, Kelly DE, Ruhnke M, Morschhauser J. Multiple molecular mechanisms contribute to a stepwise development of fluconazole resistance in clinical Candida albicans strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:3065–3072. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.12.3065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Venkateswarlu K, Denning DW, Kelly SL. Inhibition and interaction of cytochrome p450 of Candida krusei with azole antifungal drugs. J Med Vet Mycol. 1997;35:19–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukuoka T, Johnston DA, Winslow CA, de Groot MJ, Burt C, Hitchcock CA, Filler SG. Genetic basis for differential activities of fluconazole and voriconazole against Candida krusei . Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:1213–1219. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.4.1213-1219.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orozco AS, Higginbotham L.M, Hitchcock CA, Parkinson T, Falconer D, Ibrahim AS, Ghannoum MA, Filler S G. Mechanism of fluconazole resistance in Candida krusei . Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2645–2649. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.10.2645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guinea J, Sanchez-Somolinos M, Cuevas O, Pelaez T, Bouza E. Fluconazole resistance mechanisms in Candida krusei: The contribution of efflux-pumps. Med Mycol. 2006;44:575–578. doi: 10.1080/13693780600561544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zaini F, Kordbacheh P, Khedmati E, Safara M, Gharaeian N. Performance of five phenotypical methods for identification of Candida isolates from clinical materials. Iranian J Pub Health. 2006;35:25–32. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Najafzadeh MJ, Falahati M, Pooshanga Bagheri K, Fata A, Fateh R, Fateh R. Flow cytometry susceptibility testing for conventional antifungal drugs and Comparison with the NCCLS Broth Macrodilution Test. DARU. 2009;17:94–98. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saffari M, Dinehkabodi OS, Ghaffari SH, Modarressi MH, Mansouri F, Heidari M. Identification of novel p53 target genes by cDNA AFLP in glioblastoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2009;273:316–22. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ousati Ashtiani Z, Ayati M, Modarresi MH, Raoofian R, Sabah Goulian B, Greene WK, Heidari M. Association of TGIFLX/Y with prostate cancer. Med Oncol. 2009;26:73–7. doi: 10.1007/s12032-008-9086-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aarabi M, Ousati-Ashtiani Z, Nazarian A, Modarressi MH, Heidari M. Association of TGIFLX/Y mRNA expression with azoospermia in infertile men. Mol Reprod Dev. 2008;75:1761–6. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henry KW, Nickels J.T, Edlind T.D. Upregulation of erg genes in Candida species by azoles and other sterol biosynthesis inhibitors. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2000;44:2693–2700. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.10.2693-2700.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kakeya H, Miyazaki T, Miyazaki Y, Kono S. Azole resistance in Candida spp . Japanese Journal of Medical Mycology. 2003;44:87–92. doi: 10.3314/jjmm.44.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pinjon E, Moran GP, Jackson CJ, Kelly SL, Sanglard D, Coleman D.C, Sullivan DJ. Molecular mechanisms of itraconazole resistance in Candida dubliniensis . Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2003;47:2424–2437. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.8.2424-2437.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chau AS, Gurnani M, Hawkinson R, Laverdiere M, Cacciapuoti A, McNicholas PM. Inactivation of sterol 5, 6-desaturase attenuates virulence in Candida abicans . Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2005;49:3646–3651. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.9.3646-3651.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan L, Zhang J, Li M, Cao Y, Xu Z, Cao Y, Gao P, Wang Y, Jiang Y. DNA microarray analysis of fluconazole resistance in a laboratory Candida albicans strain. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin. 2008;40:1048–1060. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7270.2008.00483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Venkateswarlu K, Denning D.W, Manning NJ, Kelly S.L. Reduced accumulation of drug in Candida krusei accounts for itraconazole resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2443–2446. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.11.2443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katiyar SK, Edlind TD. Identification and expression of multidrug resistance related abc transporter genes in Candida krusei . Medical Mycology. 2001;39:109–116. doi: 10.1080/mmy.39.1.109.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lamping E, Ranchod A, Nakamura K, Tyndall JDA, Niimi K, Holmes AR, Niimi M, Cannon RD. Abc1p is a multidrug efflux transporter that tips the balance in favor of innate azole resistance in Candida krusei . Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2009;53:354–369. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01095-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clark FS, Parkinson T, Hitchcock CA, Gow NA. Correlation between rhodamine 123 accumulation and azole sensitivity in Candida species: Possible role for drug efflux in drug resistance. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 1996;40:419–425. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.2.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marichal P, Gorrens J, Coene MC, Le Jeune L, Bossche HV. Origin of differences in susceptibility of Candida krusei to azole antifungal agents. Mycoses. 1995;38:111–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1995.tb00032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dimster-Denk D, Rine J. Transcriptional regulation of a sterol-biosynthetic enzyme by sterol levels in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1996;16:3981–3989. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.8.3981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Asai K, Tsuchimori N, Okonogi K, Perfect JR, Gotoh O, Yoshida Y. Formation of azole-resistant Candida albicans by mutation of sterol 14-demethylase p450. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 1999;43:1163–1169. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.5.1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beyer A, Hollunder J, Nasheuer HP, Wilhelm T. Post-transcriptional expression regulation in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae on a genomic scale. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 2004;3:1083–1092. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400099-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]