Abstract

In Manduca sexta, pathogen recognition triggers a branched serine proteinase cascade which generates active phenoloxidase (PO) in the presence of a proPO-activating proteinase (PAP) and two noncatalytic serine proteinase homologs (SPHs). PO then catalyzes the production of reactive compounds for microbe killing, wound healing, and melanin formation. In this study, we discovered that a minute amount of PAP1 (a final component of the proteinase pathway) caused a remarkable increase in PO activity in plasma from naïve larvae, which was significantly higher than that from the same amounts of PAP1, proPO and SPHs incubated in vitro. The enhanced proPO activation concurred with the proteolytic activation of HP6, HP8, PAP1, SPH1, SPH2 and PO precursors. PAP1 cleaved proSPH2 to yield bands with mobility identical to SPH2 generated in vivo. PAP1 partially hydrolyzed proHP6 and proHP8 at a bond amino-terminal to the one cut in the PAP1-added plasma. PAP1 did not directly activate proPAP1. These results suggest that a self-reinforcing mechanism is built into the proPO activation system and other plasma proteins are required for cleaving proHP6 and proHP8 at the correct site to strengthen the defense response, perhaps in the early stage of the pathway activation.

Keywords: Insect immunity, Melanization, Hemolymph protein, Serine proteinase pathway, Clip domain

1. Introduction

Serine proteinases in vertebrates and invertebrates constitute pathways to mediate innate immunity upon tissue damage or pathogen invasion (Krem and Di Cera, 2002; Jiang and Kanost, 2000). The blood coagulation system in mammals is an example of such extracellular proteinase cascades. Positive and negative feedback loops exist in the system to control its potency and duration. Thrombin activates its upstream coagulation factors via limited proteolysis in the early stage of blood clotting (Dahlback and Villoutreix, 2005). As coagulation proceeds, thrombin binds to thrombomodulin and becomes an anticoagulant by inactivating its upstream enzymes at different sites. Serpins regulate blood coagulation by forming irreversible complexes with the clotting factors. Analogous proteinase cascades in arthropod hemolymph mediate defense responses, and serpins negatively modulate these processes. While proteinase-mediated positive feedback occurs during the establishment of dorsoventral axis in Drosophila (Dissing et al., 2001), it is unclear whether or not such mechanism exists in arthropod immune proteinase pathways (e.g. prophenoloxidase (proPO) activation system).

Insect phenoloxidases (POs) produce quinones and other reactive compounds for melanin formation, protein crosslinking, and microbe killing (Ashida and Brey, 1997; Cerenius and Söderhäll, 2004; Nappi and Christenson, 2005; Zhao et al., 2007). POs are synthesized as inactive precursors and proteolytically activated by proPO activating proteinases (PAPs) (Satoh et al., 1999; Jiang et al., 1998, 2003a and 2003b; Lee et al., 1998; Tang et al., 2006). In some insects, proPO activation requires the presence of one or two noncatalytic serine proteinase homologs (SPHs) (Kwon et al., 2000; Yu et al., 2003). The PAPs and SPHs, containing a regulatory clip domain at the amino terminus, are activated in a branched serine proteinase cascade (Kim et al. 2002). This cascade is initiated upon recognition of pathogen surface molecules by specific binding proteins. Manduca sexta hemolymph proteinase 14 precursor (proHP14) interacts with Gram-positive bacteria or fungi, self-activates, and cleaves proHP21 (Ji et al., 2004; Wang and Jiang, 2006). Active HP21 produces PAP2 and PAP3 (Gorman et al., 2007; Wang and Jiang; 2007), which generate active PO in the presence of SPH1 and SPH2. The SPH precursors are not active as a cofactor for the PAPs until a specific cleavage occurs (Lu and Jiang, 2008). To date, the activating proteinase(s) for proSPHs are not known in the tobacco hornworm. Neither is it clear whether proSPH activator(s) relate to the branch that leads to proPAP2 and proPAP3 activation.

We have isolated 27 hemolymph proteinase cDNAs from M. sexta and prepared polyclonal antisera to the recombinant proteins (Jiang et al., 2005). Using the sequence information and molecular probes, we were able to identify HPs that are involved in innate immune responses (Tong and Kanost, 2005; Tong et al., 2005; Zou et al., 2005). Some of these enzymes form covalent complexes with M. sexta serpin-4, -5 and -6 which inhibit HP1, HP6, HP8, HP17, HP21 and PAPs. In this paper, we report an unexpected finding that adding a small amount of PAP-1 to the larval plasma drastically enhanced proPO activation. Using antisera against the HPs and SPHs, we detected changes in the cell-free hemolymph which explain the large increase in PO activity. Based on results from the immunoblot analysis and in vitro activation tests, we propose a positive feedback mechanism which represents a new layer of regulation during proPO activation.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Insect rearing, hemolymph collection, protein preparation and activity assays

M. sexta eggs were purchased from Carolina Biological Supply and the larvae were reared on an artificial diet (Dunn and Drake, 1983). Hemolymph samples collected from cut prolegs of the day 3, fifth instar naïve larvae were centrifuged at 14,000g for 5 min to remove hemocytes. The plasma sample was stored at −80ºC as 20 μl aliquots. ProPO and PAP1 were purified from the larval hemolymph and cuticle extract, respectively (Jiang et al., 1997; Gupta et al., 2004). The precursors of SPH1, SPH2, and PAP1 were prepared previously (Lu and Jiang, 2008; Wang et al., 2001). PO activity and acetyl-Ile-Glu-Ala-p-nitroanilide (IEARpNA) hydrolysis were measured according to Jiang et al (2003a), with one unit defined as the amount of enzyme causing 0.001 absorbance increase in one minute.

2.2. Enhancement of proPO activation in plasma from naïve larvae

Cell-free hemolymph (1.0 μl) was incubated on ice for 60 min with buffer A (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 19 μl), purified SPHs (1.0 μl, 20 ng/μl and 18 μl buffer A), or PAP1 (1.0 μl, 20 ng/μl and 18 μl buffer A). As controls, proPO alone (1.0 μl, 100 ng/μl and 19 μl buffer A) and proPO activation mixture (100 ng proPO, 20 ng SPHs, 20 ng PAP1, and 17 μl buffer A) were incubated under the same condition prior to PO activity measurement.

2.3. Immunoblot analysis of proPO, proSPH and proHP proteolysis in the plasma

Plasma (30 μl) from naïve larvae was incubated at room temperature for 15 min with buffer A (165 μl) or PAP1 (15 μl, 20 ng/μl and 150 μl buffer A) in the presence of 0.01% 1-phenyl-2-thiourea. After being treated with SDS sample buffer containing 2-mercaptoethanol, the samples (equivalent to 1.5 μl plasma) were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Following electrotransfer and blocking, the protein blots were individually reacted with 1:2,000 diluted polyclonal antisera against proPO, PAP1, PAP2, PAP3, SPH1, SPH2, HP1, HP2, HP5, HP6, HP8, HP14, HP16, HP17, HP19, and HP21. The antigen-antibody complexes were visualized by color precipitation catalyzed by alkaline phosphatase conjugated to goat-anti-rabbit IgG (Bio-Rad).

2.4. Construction of recombinant baculoviruses for proHP6 and proHP8 production

M. sexta HP6 and HP8 cDNAs (Jiang et al., 2005) were amplified by PCR using specific primer pairs: j510 (5’-TTAGGATCCATGTGGTTAATGGTG) and j500 (5’-AGTCTCGAGAT TAGGCCAAACAATAC) for HP6; j511 (5’-TTGGGATCCGTGTGTGAACTAG) and j501 (5’-GCACTCGAGAGGTCGTAACTTTGA) for HP8. The thermal cycling conditions were: 94ºC, 1 min; 35 cycles of 94ºC for 30 s, 40ºC for 30 s and 68ºC for 2 min; 68ºC for 3 min. The PCR products (1.08 and 1.12 kb) were digested with BamHI completely and XhoI partially due to an internal XhoI site in the cDNA sequences. Following agarose gel electrophoresis, the cDNA fragments at the right size were inserted to the same sites in pFH6 (Ji et al., 2003). The resulting plasmids (proHP6/pFH6 and proHP8/pFH6) were sequenced to verify correct insertion. In vivo transposition of the expression cassette, selection of bacterial colonies carrying the recombinant bacmid, and isolation of bacmid DNA were performed according to manufacturer’s protocols (Invitrogen Life Technologies). The initial viral stocks (V0) were obtained by transfecting Spodoptera frugiperda Sf21 cells with a bacmid DNA-CellFECTIN mixture, and their titers were improved through serial infection. The V5 viral stock, containing the highest level of baculovirus, was stored at −70°C for further experiments. Expression conditions were optimized according to Ji et al (2003).

2.5. Expression of recombinant proHP6 and proHP8 in insect cells

Sf9 cells (at 2.4×106 cells/ml) in 150 ml of insect serum-free medium (Invitrogen Life Technologies) supplemented with 0.02 mM p-aminobenzamidine (pAbz) were infected with the proHP6 baculovirus stock at a multiplicity of infection of ten and grown at 27°C for 75 h with agitation at 100 rpm. The expression of proHP8 was performed under the same conditions except that Sf21 cells (400 ml) were infected by the proHP8 viral stock for 96 h.

2.6. Isolation of recombinant proHP6 and HP6

After the cells were removed by centrifugation at 5,000g for 10 min, pH of the conditioned medium was adjusted to 8.4 using 100 ml 75 mM NaOH containing 2 mM pAbz. The cell debris and fine particles were spun down by centrifugation at 10,000g, and the supernatant was applied at a flow rate of 1 ml/min onto a Q-Sepharose FF column (1.5 cm i.d. × 11 cm) equilibrated with buffer B (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 0.01% Tween-20, 1 mM pAbz). After washing with 100 ml buffer B, bound proteins were eluted from the column with a linear gradient of 0-0.5 M NaCl in 100 ml buffer B and 0.5 M NaCl in 40 ml buffer B. The proHP6 fractions (3.4 ml/tube) were combined and mixed with 0.5 ml Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) agarose at 4ºC for 1 h with gentle agitation. The suspension was packed to an empty column, and the resin was washed with 10 ml buffer C (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.01% Tween-20, 100 mM NaCl) containing 10 mM imidazole and eluted with 250 mM imidazole in buffer C (0.5 ml/fraction). The HP6 fractions from the Q-column were affinity purified under the same conditions.

2.7. Partial purification of recombinant proHP8 and HP8

HP8 was partially purified from 200 ml conditioned medium on Q-Sepharose and Ni2+-NTA agarose columns as described above. ProHP8 was purified from the cell lysate from 400 ml culture: infected cells harvested by centrifugation at 5,000g for 10 min were treated with 40 ml of 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 8.0, 1% Nonidet P-40, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, for 10 min at 4ºC. The cell lysate was centrifuged at 10,000g for 10 min, and the supernatant (40 ml) was subjected to nickel affinity chromatography.

2.8. Possible cleavage of purified proPAP1, proSPHs, proHP6 and proHP8 by PAP-1

Recombinant proPAP1 isolated from the baculovirus-insect cell system (2.0 μl, 66 ng/μl) was incubated with purified PAP1 (2.0 μl, 20 ng/μl and 10 μl buffer A) at room temperature for 60 min. In the negative controls, the same amounts of proPAP1 (40 ng) and PAP1 (132 ng) were separately mixed with buffer A (12 μl) under the identical condition. The reaction mixtures were subjected to 12% SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis. IEARase activities in the duplicate reactions were measured according to Jiang et al (2003a).

Purified proSPH1 (100 ng, 1.0 μl+ buffer A, 22 μl), proSPH2 (100 ng, 1.0 μl + buffer A, 22 μl), or both proSPHs (100 ng + 100 ng + buffer A, 21 μl) were incubated with PAP1 (1.0 μl, 20 ng/μl) on ice for 60 min. In the negative controls, the same amount of proSPH1 or proSPH2 (100 ng) were mixed with buffer A (23 μl) under the identical conditions. Half of the mixtures were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis using SPH1 antibodies, and the other half using SPH2 antibodies. ProPO activation was determined by incubating proPO (0.4 μg, 1.0 μl), PAP1 (20 ng, 1.0 μl) with proSPH1 (50 ng, 0.5 μl + buffer A, 21.5 μl), proSPH2 (50 ng, 0.5 μl + buffer A, 21.5 μl), or both SPHs (50 ng + 50 ng + buffer A, 21 μl) on ice for 1 h prior to the PO activity assay (Jiang et al., 2003a). Negative controls of proPO only (400 ng), proPO and PAP1 (400 ng + 20 ng), proPO and proSPHs (400 ng + 25 ng + 25 ng) were also employed.

Processing of proHP6 and proHP8 by PAP1 was examined under similar conditions. Purified proHP6 (80 ng, 1.0 μl + buffer A, 10 μl), proHP8 (40 ng, 2.0 μl + buffer A, 9 μl), or both (80 ng + 40 ng + buffer A, 8 μl) were incubated with PAP1 (20 ng, 1.0 μl) at 37ºC for 1 h. Total volume of the negative controls [proHP6 (80 ng), proHP8 (40 ng), and both (80 ng + 40 ng)] was also adjusted to 12 μl with buffer A. Half of the mixtures were analyzed by 10% SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis using HP6 antibodies, and the other half using HP8 antibodies. Following pre-incubation with buffer A at 37ºC for 1 h (in a total volume of 25 μl), PAP1 (1.0 μl, 20 ng/μl), proHP6 (1.0 μl, 80 ng/μl), proHP8 (2.0 μl, 20 ng/μl), PAP1 and proHP6 (20 ng + 80 ng), or PAP1 and proHP8 (20 ng + 40 ng) was subjected to IEARase activity assay.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Discovery of PAP1-mediated enhancement of proPO activation

Our previous study demonstrated that HP14 (generated by incubating proHP14 with curdlan, and β-1,3-glucan recognition protein-2) or HP21 (generated by incubating proHP21 with HP14) significantly enhanced proPO activation in cell-free hemolymph from the naïve larvae (Wang and Jiang, 2006 and 2007). In a control experiment, we added a small amount of PAP1 to the plasma and measured PO activity after incubation on ice for 60 min. Since PAP1 (unlike HP14 or HP21) is a final component of the proPO activation system and there is little SPH1 or SPH2 to act as its auxiliary factor, we anticipated detecting a low PO activity in this negative control. Much to our surprise, a high level of PO activity (>50 U) was developed.

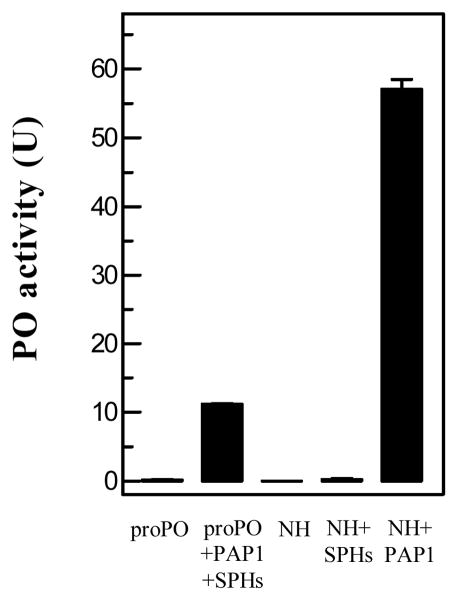

We repeated the experiment with proper controls and corroborated the phenomenon (Fig. 1). While proPO and cell-free hemolymph had little PO activity, adding 20 ng PAP1 to the plasma (1.0 μl) greatly enhanced the proPO activation (Fig. 1, 57.0 U). In the control, incubation of 100 ng proPO, 20 ng SPHs and 20 ng PAP1 yielded much lower PO activity (10.5 U). Note that the SPHs used here were at higher concentration than in the hemolymph of naïve larvae: SPHs are present at a high concentration (50 μg/ml) in plasma of the late wandering larvae (Wang and Jiang, 2004) but they exist as precursors in plasma of the feeding larvae. The PAP1 level in the control hemolymph is also minimal, since adding 20 ng SPHs to the plasma failed to generate much active PO (Fig. 1). The proPO concentration in larval hemolymph (40 μg/ml) (Jiang et al., 1997) is lower than the purified proPO (100 μg/ml). Therefore, the actual PO activity difference between the control and test should have been even larger and there has to be a mechanism to account for the drastic enhancement in proPO activation.

Fig. 1. PAP1-mediated enhancement of proPO activation in cell-free hemolymph from the naïve M. sexta larvae.

As described in Methods and Materials, the cell-free hemolymph samples (1.0 μl, NH) from naive larvae were separately incubated with buffer, SPHs, or PAP1 on ice for 60 min. In the control set, proPO was incubated with buffer or PAP1 and SPHs. PO activity was determined and plotted in the bar graph as mean ± SD (n = 3).

3.2. Changes accompanying the enhancement of proPO activation

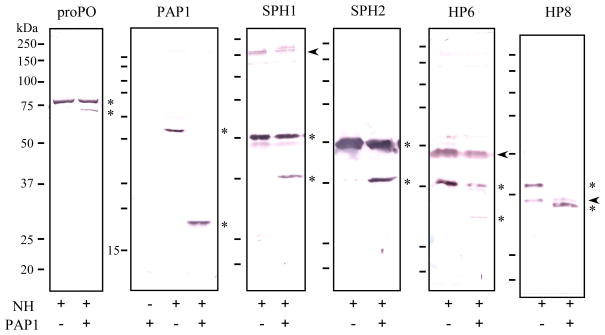

To explore the possible mechanism for this major increase in PO activity, we first examined the hemolymph samples using polyclonal antibodies against components of the proPO activation reaction. ProPO polypeptide-2 in the untreated plasma migrated as a single band at 80 kDa and about 1/5 of the proenzyme was converted to 74 kDa PO polypeptide-2 after PAP1 had been added (Fig. 2), which agreed with the large increase in PO activity. Addition of a small amount of purified PAP1 stimulated a substantial increase in the activation of endogenous proPAP1: the 44 kDa zymogen was completely converted to the active form. The exogenous PAP1 itself was below the detection limit of immunoblot analysis. As demonstrated previously (Wang et al., 2001; Gupta et al., 2004), PAP1 antibodies strongly reacted with the light chain of PAP1 in the activated plasma sample and the signal for PAP1 heavy chain was much weaker.

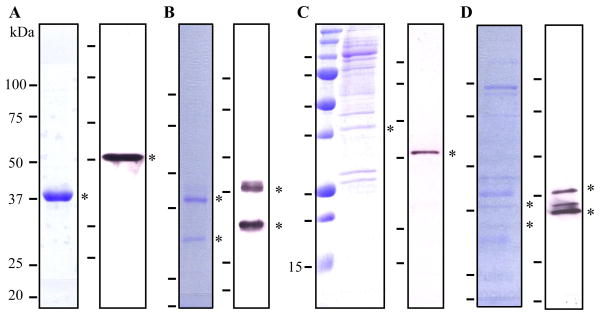

Fig. 2. Limited proteolysis of M. sexta PO, PAP1, SPH, and HP precursors accompanying the large increase in PO activity.

As described in Methods and Materials, the plasma samples were incubated with buffer or PAP1 at room temperature for 15 min. The reaction mixtures were treated with SDS sample buffer and separated by SDS-PAGE (12% for PAP1, 10% for the others). Following electrotransfer, the protein blots were separately incubated with 1:2,000 diluted antisera against proPO polypeptide-2, PAP1, SPH1, SPH2, HP6 and HP8, as marked on top of each panel. The antibody-antigen complexes were detected using alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibodies. Sizes and positions of the molecular weight markers (250, 150, 100, 75, 50, 37, 25, and 20 kDa) are shown as short bars on the left of each panel, whereas positions of the zymogens and cleavage products are indicated by *. The nonspecific recognition of hemolymph proteins is marked with an arrowhead.

We observed specific proteolysis of proSPH1 and proSPH2 after addition of PAP1 to plasma. Like PO and PAP1, these proteinase-like molecules were present as inactive precursors (53 and 50 kDa) before PAP1 treatment. The cleavage products were identical in their heavy chain sizes (37 kDa and 37.5 kDa) to SPH1 and SPH2 purified from hemolymph of the bar-stage larvae (Wang and Jiang, 2004). Although we did not know whether or not PAP1 directly processed the proSPHs, its inclusion in the plasma led to the generation of SPHs as a factor responsible for the drastic enhancement of proPO activation.

Did proteolysis of other hemolymph proteinases (HPs) occur after PAP1 treatment? To address this question, we tested possible changes in mobility of the other HPs by immunoblot analyses. There was no major difference in HP1, HP2, HP5, HP14, HP16, HP17, HP19, HP21, PAP2 and PAP3 precursor levels (data not shown). Since HP14, HP21, PAP2 and PAP3 are components of the proPO activation system (Ji et al., 2004; Wang and Jiang, 2005 and 2007; Maureen et al., 2007), the enhancement in proPO activation did not appear to involve the entire cascade in the naïve larval plasma. On the other hand, we observed changes in mobility and levels of HP6 and HP8 (Fig. 2). Their precursors in the unactivated plasma migrated to around 38 and 42 kDa positions, respectively. After PAP1 treatment, 3/4 of proHP6 disappeared and there was a concomitant appearance of a 29 kDa immunoreactive band, which may correspond to the catalytic domain of HP6. ProHP8 was completely converted to a 32 kDa band, perhaps representing the catalytic heavy chain of HP8. These changes in HP6 and HP8 may or may not be related to the proteolytic activation of proPAP1, proSPHs, or proPO.

3.3. Cleavage of purified proPAP1, proSPHs, proHP6 and proHP8 by PAP1

To test whether PAP1 can directly cleave proPAP1, proSPHs, proHP6 or proHP8, we expressed these five precursor proteins (Wang et al., 2001; Lu and Jiang, 2008; this work) and separately tested their possible cleavage by purified PAP1.

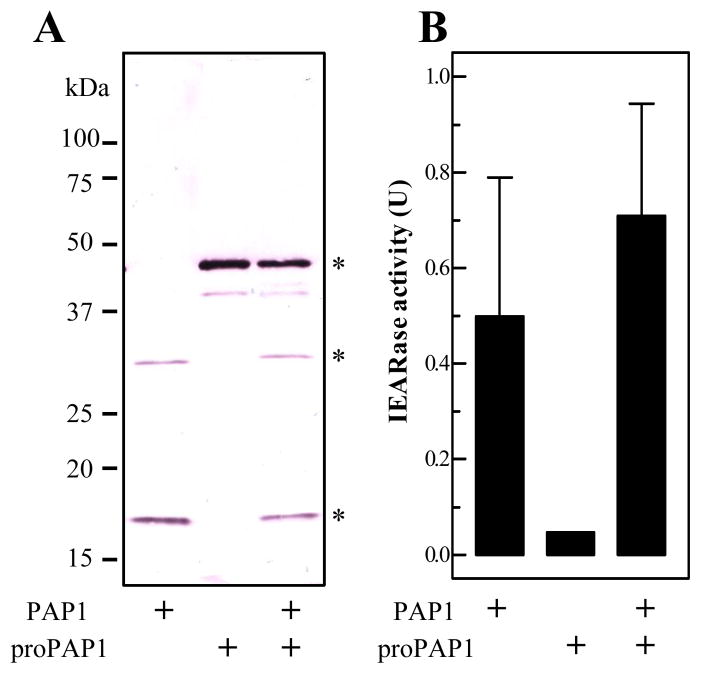

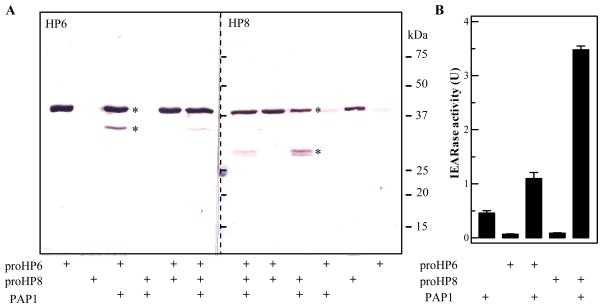

PAP1 did not cut proPAP1 (Fig. 3A), even in the presence of SPHs (data not shown). This is consistent with the observation that only a small portion of proPAP1 became active during membrane concentration (Yu et al., 2003). PAP1 hydrolyzed IEARpNA but proPAP1 did not (Fig. 3B). Incubation of the enzyme and zymogen did not yield a statistically significant increase in IEARase activity.

Fig. 3. Examination of proPAP1 cleavage and IEARase activity after treatment of M. sexta PAP1.

Purified proPAP1 was incubated with buffer or PAP1 as described in Methods and Materials. The reaction mixtures (and PAP1 control) were subjected to 12% SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis using PAP1 antibodies (A). The positions of proPAP1, PAP1 catalytic domain, and PAP1 regulatory light chain are marked with *. In the duplicate reactions, IEARase activities were measured and plotted in the bar graph as mean ± SD (n = 3) (B).

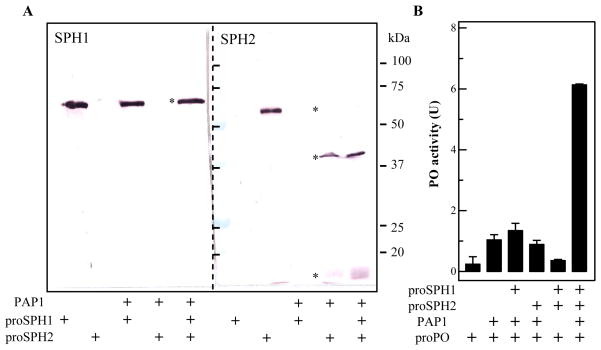

PAP1 did not cut proSPH1 (Fig. 4A), but it did cleave proSPH2 almost completely. Since the cleavage product had an apparent Mr similar to SPH2 in the hemolymph (Fig. 2; Wang and Jiang, 2003), PAP1 perhaps participates in the generation of its own cofactor during proPO activation. The proteolytic activation sites of proPO and proSPH2 are both Arg*Phe, where * denotes the scissile bond. To further explore this new function of PAP1, we examined a possible cofactor activity of SPH2: proPO alone, proPO with proSPH1 and proSPH2, and proPO with PAP1 all had little PO activity; no significant increase occurred after proPO and PAP1 had been incubated with proSPH1 or proSPH2 separately; highest PO activity developed when proPO, PAP1 and proSPHs were present at the same time (Fig. 4B). Because PAP1 did not cleave proSPH1 in the presence of proSPH2 and proPO (data not shown), PAP1 activation of proSPH2 apparently generated a functional cofactor containing proSPH1. The highest PO activity, however, was much lower than that observed when both SPH1 and SPH2 were present in their active form (Fig. 1). All these results are consistent with the published data obtained using column fractions (Lu and Jiang, 2008).

Fig. 4. Proteolytic activation of the purified proSPHs (A) and determination of the cofactor activity (B).

(A) As described in Methods and Materials, purified proSPH1, proSPH2, or both were reacted with PAP1, treated with SDS sample buffer, and resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE along with the control samples of proSPH1 and proSPH2 only. Immunoblot analysis was performed using 1:2,000 diluted SPH1 (left) or SPH-2 (right) antiserum as the first antibody. The positions of proSPHs and their cleavage products are marked with *. Sizes and positions of the marker proteins are indicated. (B) ProPO was added to the duplicate reactions or buffer and incubated on ice for 1 h. The PO activity was measured and plotted as mean ± SEM (n = 3).

In order to test whether purified PAP1 directly activates proHP6 and proHP8, we constructed recombinant baculoviruses to express the proenzymes in insect cells. The hexahistidine-tagged proHP6 reached 1.0 mg/L in the conditioned medium at 75 h after infection. From 150 ml cell culture, we obtained 150 μg proHP6. A small amount of HP6 was spontaneously activated during ion exchange and affinity chromatography. The recombinant proHP6 was essentially pure and migrated to the 38 kDa position on the SDS gel, whereas HP6 contained proHP6 and several other proteins (Fig. 5). Under similar expression conditions, proHP8 was secreted to the medium but mostly cleaved by an unknown proteinase released by baculovirus-infected insect cells. We isolated HP8 from the culture medium, which is contaminated with proHP8 and other proteins. To obtain intact proHP8 for PAP1 activation test, we purified proHP8 from the cell lysate by Ni-affinity chromatography. The intracellular proHP8 was a minor component of the protein preparation but it migrated as a 42 kDa single band recognized by the HP8 antibodies.

Fig. 5. SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis of purified recombinant M. sexta proHP6 (A), HP6 (B), proHP8 (C) and HP8 (D).

In each panel, a Coomassie blue stained gel (left) and immunoblot (right) are shown. Positions of proHP6, HP6, proHP8, and HP8 are marked with *. The short bars on the right of each strip indicate the positions of molecular weight markers (100, 75, 50, 37, 25, 20 kDa).

After purified proHP6 was incubated with PAP1, most of the proHP6 remained intact (Fig. 6A). A minor immunoreactive band was detected at the 32 kDa position different from HP6 heavy chain (28 kDa) generated in the plasma (Fig. 2). The cleavage of proHP8 from the cell lysate by PAP1 was also incomplete and at a position different from its putative activation site: a weak doublet was recognized by HP8 antibodies, whose size significantly differed from the HP8 heavy chain (Fig. 2). However, after proHP6 or proHP8 was reacted with PAP1, there was a statistically significant increase in IEARase activity (Fig. 6B). In accordance to the predicted trypsin-like specificity of HP6 and HP8, their cleavage products generated by PAP1 may have hydrolyzed this synthetic substrate. Alternatively, PAP-1 may have become more active by associating with one or more of the reaction components.

Fig. 6. Examination of proHP6 and/or proHP8 cleavage (A) and IEARase activity (B) after M. sexta PAP1 treatment.

(A) Purified proHP6, proHP8, or both were reacted with PAP1 at 37ºC for 60 min, treated with SDS sample buffer, and resolved by 12% SDS-PAGE along with the control samples of proHP6 and proHP8. Immunoblot analysis was performed using 1:2,000 diluted HP6 (left) or HP8 (right) antiserum as the first antibody. (B) In the duplicate reactions, IEARase activities were measured and plotted in the bar graph as mean ± SEM (n = 3).

3.4. Possible mechanisms for PAP1-boosted proPO activation and other immune responses

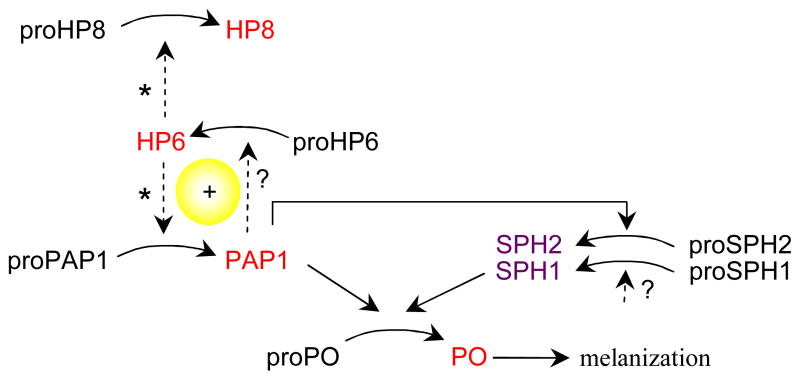

Based on the differences in proteolytic cleavage of proPAP1, proSPH1, proHP6, and proHP8 between the hemolymph and purified proteins treated with PAP1, we suggest that PAP1 and another plasma factor are directly or indirectly responsible for the cleavage activation of HP6, HP8 and PAP1 precursors at the correct sites (Fig. 7). PAP1, together with the unknown protein, may act on proHP6 to generate HP6. Then, according to a model of M. sexta proPO activation system (Tong et al., 2005), HP6 cleaves proHP8 to form HP8. While HP21 activates proPAP2 (Wang and Jiang, 2007) and proPAP3 (Gorman et al., 2007), Factor Xa-activated HP6 cleaves proHP8 and proPAP1 at the predicted activation site (An et al., unpublished results). Taken together, these data suggest a positive feedback loop of PAP1 and HP6, which functions in the presence of one or more plasma factors (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7. A model for PAP1-stimulated proPO activation.

Based on this study, PAP1 activates proSPH and, to further reinforce PO production and melanization, PAP1 may cleave proHP6 and proSPH1 at the correct site in the presence of adaptor proteins (dashed arrow with ?). It is also possible that the unknown plasma factors are precursors of the proHP6- and proSPH1-activating proteinases, which are activated by PAP1 cleavage. In order to better explain the PAP1-enhanced proPO activation, we include the unpublished results (Kanost, personal communication) showing that HP6 activates proPAP1 and proHP8 (dashed arrow with *).

PAP1 cleaved proSPH2 at the right position (Fig. 4A), but it is unclear if PAP1 in the presence of an unknown adaptor processes proSPH1 or a different HP activated by PAP1 serves as an activator of proSPH1. Cleaved SPH1 must form a high Mr complex with SPH2 in order to be fully functional as the auxiliary factor for the PAPs (Lu and Jiang, 2008).

3.5. Concluding remarks

M. sexta serves as a useful biochemical model in the research on insect antimicrobial responses (Kanost et al., 2004; Jiang, 2008). Over the years, molecular probes (e.g. cDNA clones and antisera) and knowledge have accumulated for in-depth investigation of molecular mechanisms underlying various defense responses. Among them, the proPO activation represents one of the best studied systems in arthropods. In this work, we have discovered that PAP1, a terminal component of the pathway, not only cleaves proPO but also enhances the reaction by generating SPH2 (Fig. 7). Moreover, in the presence of unknown plasma factors, a minute amount of PAP1 somehow led to the activation of HP6, HP8, PAP1 and SPH1 precursors. Although detailed information is unclear at this time, our results indicate the existence of a positive feedback mechanism. Such reinforcement may be critical in rapid wound healing and pathogen killing during the early stage of defense reaction. To the best of our knowledge, there is no previous report that such positive regulation occurs in a pathway of insect immune proteinases.

An earlier model indicated that distinct enzyme cascades may exist in M. sexta hemolymph to mediate proteolytic activation of PO, spätzle and paralytic peptide precursors (Kanost et al., 2001). This work suggests some HPs (e.g. PAP1) might function in more than one pathway and these pathways are intricately linked and represent components of a unified proteinase network triggered upon recognition of pathogens or aberrant tissues.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Michael Kanost, Jack Dillwith, and Junpeng Deng for their helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM58634 (to H.J.). This article was approved for publication by the Director of Oklahoma Agricultural Experimental Station and supported in part under project OKLO2450.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ashida M, Brey PT. Recent advances on the research of the insect prophenoloxidase cascade. In: Brey PT, Hultmark D, editors. Molecular Mechanisms of Immune Responses in Insects. Chapman & Hall; London: 1998. pp. 135–172. [Google Scholar]

- Cerenius L, Söderhäll K. The prophenoloxidase-activating system in invertebrates. Immunol Rev. 2004;198:116–126. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlback B, Villoutreix BO. The anticoagulant protein C pathway. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:3310–3316. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dissing M, Giordano H, DeLotto R. Autoproteolysis and feedback in a protease cascade directing Drosophila dorsal-ventral cell fate. EMBO J. 2001;20:2387–2393. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.10.2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn P, Drake D. Fate of bacteria injected into naïve and immunized larvae of the tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta. J Invert Pathol. 1983;41:77–85. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman MJ, Wang Y, Jiang H, Kanost MR. Manduca sexta hemolymph proteinase 21 activates prophenoloxidase activating proteinase 3 in an insect innate immune response proteinase cascade. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:11742–11749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611243200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Wang Y, Jiang H. Purification and characterization of Manduca sexta prophenoloxidase-activating proteinase-1 (PAP-1), an enzyme involved in insect immune responses. Protein Exp Purif. 2005;39:261–268. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji C, Wang Y, Guo X, Hartson S, Jiang H. A pattern recognition serine proteinase triggers the prophenoloxidase activation cascade in the tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:34101–34106. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404584200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji C, Wang Y, Ross J, Jiang H. Expression and in vitro activation of Manduca sexta prophenoloxidase-activating proteinase-2 precursor (proPAP-2) from baculovirus-infected insect cells. Protein Express Purif. 2003;29:235–243. doi: 10.1016/s1046-5928(03)00020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H. The biochemical basis of antimicrobial responses in Manduca sexta. Insect Science. 2008;15:53–66. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Kanost MR. The clip-domain family of serine proteinases in arthropods. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2000;30:95–105. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(99)00113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Wang Y, Gu Y, Guo X, Zou Z, Scholz F, Trenczek TE, Kanost MR. Molecular identification of a bevy of serine proteinases in Manduca sexta hemolymph. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;35:931–943. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Wang Y, Kanost MR. Pro-phenol oxidase activating proteinase from an insect, Manduca sexta: a bacteria-inducible protein similar to Drosophila easter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:12220–12225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Wang Y, Ma C, Kanost MR. Subunit composition of pro-phenol oxidase from Manduca sexta: molecular cloning of subunit proPO-p1. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1997;27:835–850. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(97)00066-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Wang Y, Yu XQ, Kanost MR. Prophenoloxidase-activating proteinase-2 (PAP-2) from hemolymph of Manduca sexta: a bacteria-inducible serine proteinase containing two clip domains. J Biol Chem. 2003a;278:3552–3561. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205743200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Wang Y, Yu XQ, Zhu Y, Kanost MR. Prophenoloxidase-activating proteinase-3 (PAP-3) from Manduca sexta hemolymph: a clip-domain serine proteinase regulated by serpin-1J and serine proteinase homologs. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2003b;33:1049–1060. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(03)00123-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanost MR, Jiang H, Wang Y, Yu X, Ma C, Zhu Y. Hemolymph proteinases in immune responses of Manduca sexta. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2001;484:319–328. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1291-2_32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanost MR, Jiang H, Yu XQ. Innate immune responses of a lepidopteran insect, Manduca sexta. Immunol Rev. 2004;198:97–105. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.0121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MS, Baek MJ, Lee MH, Park JW, Lee SY, Söderhäll K, Lee BL. A new easter-type serine protease cleaves a masquerade-like protein during prophenoloxidase activation in Holotrichia diomphalia larvae. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:39999–40004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205508200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krem MM, Di Cera E. Evolution of enzyme cascades from embryonic development to blood coagulation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:67–74. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)02007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon TH, Kim MS, Choi HW, Joo MY, Lee BL. A masquerade-like serine proteinase homologue is necessary for phenoloxidase activity in the coleopteran insect, Holotrichia diomphalia larvae. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:6188–6196. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SY, Kwon TH, Hyun JH, Choi JS, Kawabata SI, Iwanaga S, Lee BL. In vitro activation of pro-phenol-oxidase by two kinds of pro-phenol-oxidase-activating factors isolated from hemolymph of coleopteran, Holotrichia diomphalia larvae. Eur J Biochem. 1998;254:50–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2540050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z, Jiang H. Expression of Manduca sexta serine proteinase homolog precursors in insect cells and their proteolytic activation. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;38:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nappi AJ, Christensen BM. Melanogenesis and associated cytotoxic reactions:applications to insect innate immunity. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;35:443–459. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh D, Horii A, Ochiai M, Ashida M. Prophenoloxidase-activating enzyme of the silkworm, Bombyx mori: purification, characterization and cDNA cloning. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:7441–7453. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.11.7441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H, Kambris Z, Lemaitre B, Hashimoto C. Two proteases defining a melanization cascade in the immune system of Drosophila. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:28097–28104. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601642200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Y, Jiang H, Kanost MR. Identification of plasma proteases inhibited by Manduca sexta serpin-4 and serpin-5 and their association with components of the prophenol oxidase activation pathway. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:14932–14942. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500532200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Y, Kanost MR. Manduca sexta serpin-4 and serpin-5 inhibit the prophenol oxidase activation pathway: cDNA cloning, protein expression, and characterization. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:14923–14931. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500531200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Jiang H, Kanost MR. Expression and purification of Manduca sexta prophenoloxidase-activating proteinase precursor (proPAP) from baculovirus-infected insect cells. Protein Express Purif. 2001;23:328–337. doi: 10.1006/prep.2001.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Jiang H. Prophenoloxidase (proPO) activation in Manduca sexta: an analysis of molecular interactions among proPO, proPO-activating proteiase-3, and a cofactor. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;34:731–742. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Jiang H. Interaction of β-1,3-glucan with its recognition protein activates hemolymph proteinase 14, an initiation enzyme of the prophenoloxidase activation system in Manduca sexta. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9271–9278. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513797200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Jiang H. Reconstitution of a branch of Manduca sexta prophenoloxidase activation cascade in vitro: Snake-like hemolymph proteinase 21 cleaved by HP14 activates prophenoloxidase-activating proteinase-2 precursor. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;37:1015–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu XQ, Jiang H, Wang Y, Kanost MR. Nonproteolytic serine protease homologs are involved in prophenoloxidase activation in the tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;33:197–208. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(02)00191-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao P, Li Jiajing, Wang Yang, Jiang H. Broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity of the reactive compounds generated in vitro by Manduca sexta phenoloxidase. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;37:952–959. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Z, Jiang H. Manduca sexta serpin-6 regulates immune serine proteinases PAP-3 and HP8: cDNA cloning, protein expression, inhibition kinetics, and function elucidation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:14341–14348. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500570200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]