To the Editor

Although gemcitabine is the first-line therapy for locally advanced pancreatic cancer, this treatment has not been satisfactory due to severe drug resistance. To circumvent gemcitabine resistance, numerous phase II and III studies have attempted combining of various chemotherapeutic agents with gemcitabine. However, there have not been any promising regimens, which consistently show clinically meaningful survival benefits (1).

Recent developments in small molecule inhibitors, which target various protein kinases, have enabled new combinational approaches to treat drug resistant tumors (2). The most widely approached target is EGFR, which exhibits aberrant activity and results in drug resistance in pancreatic cancer. Currently, 18 clinical trials combining gemcitabine and EGFR inhibitors in the United States (http://clinicaltrials.gov) are either ongoing or completed. Although erlotinib, one of EGFR inhibitors, has shown a small but statistically significant outcome, combination treatments with other EGFR inhibitors have not demonstrated effective improvements (3). However, emerging consensus is that targeting protein kinases will be effective treatment options for advanced pancreatic cancer in the near future. Thus, there are serious efforts to probe new targets for combination strategies with DNA damaging drugs. For efficient isolation of new targetable protein kinases and their inhibitors, we recently explored a series of protein kinase inhibitors (PKIs) and identified several potential target kinases and corresponding PKIs, which can potentiate gemcitabine efficacy in pancreatic cancer treatment.

Materials and Methods

To explore the synergistic effect of each PKI with gemcitabine, we measured cell viability of MiaPaCa2 cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA), one of gemcitabine resistant pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cell lines, using MTT (3-(4,5-dimethyl) ethiazole) assays after treatment of each PKI (1 or 10 μM) alone or in combination with gemcitabine (0.1 μM). In order to demonstrate a synergistic effect between PKIs and gemcitabine, we made up an equation called synergy index (SI): [SI] = −log2 ([viability in drug combination]/[viability in PKI treatment]). When SI is equal or greater than 0.6, which is more than a 33% decrease of cell viability in combination with gemcitabine compared to PKIs alone, we called it as a marked synergistic effect. The combination index (CI) was determined using CompuSyn software (ComboSyn, Inc., Paramus, NJ) after measuring viabilities in single or combinational treatments of PKIs and gemcitabine at various concentrations in a 1:10 molar ratio (gemcitabine:PKI).

Results and Discussion

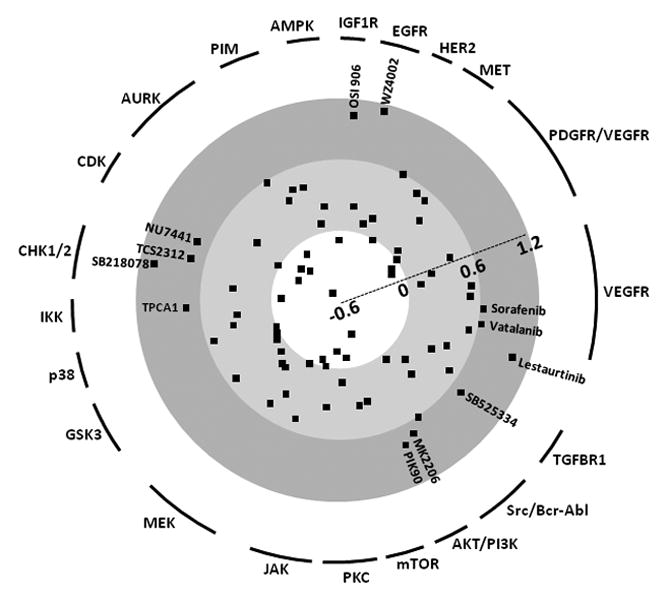

Using our PKI screening approaches, we identified 12 candidates (SI≥0.6) out of 76 PKIs targeting a broad range of protein kinases (Fig. 1). Six PKIs target receptor tyrosine kinases (e.g. EGFR and IGF1R) and six are serine/threonine kinase (e.g. PI3K and IKK) inhibitors. These PKIs can be divided into three groups according to current status of clinical trial: 1) PKIs which are in clinical trials, 2) newly identified PKIs, but whose target kinases are in clinical trials with other relevant PKIs or monoclonal antibodies, and 3) newly identified PKIs whose target kinases are not in clinical studies. These three groups are discussed below.

Figure 1.

Synergy indices of 76 protein kinase inhibitors at molar ratio 1:10 (gemcitabine:PKI). Since most PKIs have multiple targets, we classified them by their representative target kinases, which have the lowest EC50. PKIs showing synergism (SI > 0.6) are indicated.

In the first group of PKIs already being investigated in clinical trials, targeting VEGFR-mediated angiogenesis has been a good candidate and actively evaluated with either humanized antibodies or kinase inhibitors. Despite the fact that vatalanib (SI=0.64) and sorafenib (SI=0.66) efficiently impaired tumor blood vessel angiogenesis and tumor growth by targeting Raf and VEGFR in mouse models, no promising benefit was reported by phase II studies in human pancreatic cancer (4). Similarly, lestaurtinib (CEP-701, multi-target kinase inhibitor including Trk) showed a synergistic effect in combination with gemcitabine (SI=0.98) in our study, but failed to exhibit therapeutic benefits in a phase I trial in advanced pancreatic cancer (5).

In the second group, actively being pursued targets include EGFR, PI3K, and IGF1R. In our study, we included three PKIs for targeting EGFR and found that WZ4002 showed best efficacy (SI=1.02). Since erlotinib showed limited survival benefit, it would be worthy to examine WZ4002 for enhancement of EGFR targeted therapy. The AKT/PI3K/mTOR axis plays a pivotal role in cell viability directing various downstream kinases and several clinical trials have attempted combinations with DNA damaging drugs other than gemcitabine. Since the combination of MK2206 (AKT inhibitor, SI=0.69) or PIK90 (PI3K inhibitor, SI=0.74) with gemcitabine reduced cell survival, this signaling axis is a good target for clinical trials. However, mTOR inhibitors failed to meet our criteria (SI≥0.6). Also, blocking IGF1R signaling inhibits AKT and downstream MAPK signaling resulting in prevention of tumor cell growth and survival (6). Four clinical trials are currently using IGF1R monoclonal antibodies. OSI-906 (IGF1R inhibitor, SI=0.94) might be worth of clinical trial. Targeting Chk1 has well sustained biochemical in vitro evidence. When Chk1 activity is abrogated, p53-defective (50% of human cancer) cells fail in the cell cycle arrest which is caused by DNA damaging agents and results in mitotic catastrophe (7). Currently, AZD7762 is under evaluation in a Phase I clinical trial.

In the third and last group, we found three new potential combinational partners for gemcitabine: TPCA1, SB525334, and NU7441. Upregulation and constitutive activation of NFκB has frequently been reported in pancreatic cancer and gemcitabine resistant cells also exhibit high level of NFκB activity. Thus, NFκB is an attractive therapeutic target for gemcitabine refractory tumors. The NFκB signal transduction cascade is masked by IκB, which is dissociated from NF-κB when phosphorylated by IKK. Since the most relevant approach is a clinical trial with celecoxib (targeting Cox2), which has an inhibitory effect on IKK at high doses, an IKK specific inhibitor (TPCA1, SI=0.73) can be a good candidate for targeting this pathway. TGFβ also plays a key role in tumor progression and metastasis of many different types of tumor cells. Furthermore, it is linked to the induction of the epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) (8), whose biochemical parameters are shared with gemcitabine resistant cells (9). In this context, SB525334 (TGFβ receptor I inhibitor, SI=0.71) might show promising efficacy for gemcitabine resistance. In addition, DNA-PK inhibitors (NU7441, SI=0.72) can preferentially potentiate the efficacy of DNA damaging agents because its function is recognizing DNA damage during cell cycle progression. To confirm primary screening results, we further analyzed CI50 (10) for several of the promising PKIs. All the tested PKIs showed significantly low CI50 values (0.13 −0.71) (Table 1). As an experimental control, we also measured the effect of AT9283 (CI50=1.50), an Aurora kinase inhibitor, which exhibited the lowest SI value (SI=−0.52). These data indicate that our screening approaches are proficient in identifying new target kinases and candidate PKIs.

Table 1.

Combination indices of PKIs which potentiate gemcitabine cytotoxicity.

| PKI | Target | EC50 | CI50 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lestaurtinib | Trk | 1.32 | 0.13 |

| OSI906 | IGF1R | 7.55 | 0.18 |

| SB525334 | TGFBR1 | 66* | 0.71 |

| TPCA1 | IKK2 | 47.70 | 0.38 |

| PIK90 | PI3K | 12.69 | 0.23 |

| AT9283 | AURK | 0.38 | 1.50 |

EC50, half maximal effective concentration (μM); CI50, combination index at EC50; CI50>1, antagonism; CI50<1, synergy;

% of viability at maximum concentration (50 μM).

Since there are no effective therapies to circumvent the resistance to gemcitabine, systematic approaches performed in this work might be helpful to further understand the biochemical pathways that facilitate gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic cancer and might provide a clue for directing a new strategy of development in drug combination therapy.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by Susan G. Komen for the Cure (FAS0703858), National Institute of Health (1R03CA152530). This research was also supported by WCU (World class University) program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (R31-10069).

Contributor Information

Young Bin Hong, Department of Oncology, Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, Georgetown University, Washington, DC. Department of Nanobiomedical Science and WCU Research Center of Nanobiomedical Science, Dankook University, Cheonan, Republic of Korea.

Jung Soon Kim, Department of Nanobiomedical Science and WCU Research Center of Nanobiomedical Science, Dankook University, Cheonan, Republic of Korea.

Yong Weon Yi, Department of Oncology, Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, Georgetown University, Washington, DC.

Yeon-Sun Seong, Department of Nanobiomedical Science and WCU Research Center of Nanobiomedical Science, Dankook University, Cheonan, Republic of Korea.

Insoo Bae, Department of Oncology and Department of Radiation Medicine, Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, Georgetown University, Washington DC. Department of Nanobiomedical Science and WCU Research Center of Nanobiomedical Science, Dankook University, Cheonan, Republic of Korea.

References

- 1.Gounaris I, Zaki K, Corrie P. Options for the treatment of gemcitabine-resistant advanced pancreatic cancer. JOP. 2010;11:113–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen P. Protein kinases: the major drug targets of the twenty-first century? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1:309–315. doi: 10.1038/nrd773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hidalgo M. Pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1605–1617. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0901557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Khoueiry AB, Ramanathan RK, Yang DY, et al. A randomized phase II of gemcitabine and sorafenib versus sorafenib alone in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. Invest New Drugs. 2011 Mar 22; doi: 10.1007/s10637-011-9658-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan E, Mulkerin D, Rothenberg M, et al. A phase I trial of CEP-701 + gemcitabine in patients with advanced adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Invest New Drugs. 2008;26:241–247. doi: 10.1007/s10637-008-9118-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dimou AT, Syrigos KN, Saif MW. Novel agents for the treatment of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: any light at the end of the tunnel? Highlights from the “2010 ASCO Annual Meeting”. Chicago, IL, USA. June 4–8, 2010. JOP. 2010;11:324–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blasina A, Hallin J, Chen E, et al. Breaching the DNA damage checkpoint via PF-00477736, a novel small-molecule inhibitor of checkpoint kinase 1. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:2394–2404. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-2391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JM, Dedhar S, Kalluri R, et al. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition: new insights in signaling, development, and disease. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:973–981. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200601018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh A, Settleman J. EMT, cancer stem cells and drug resistance: an emerging axis of evil in the war on cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29:4741–4751. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chou TC. Theoretical basis, experimental design, and computerized simulation of synergism and antagonism in drug combination studies. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:621–681. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]