Abstract

Background/Aims

Combination treatment consisting of hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy with epirubicin and cisplatin (HAIC-EC) and systemic infusion of low-dose 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) are sometimes effective against advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). However, there is no effective treatment for advanced HCCs with arterioportal shunts (APS) or arteriovenous shunts (AVS).

Methods

We investigated a response and adverse events of a new combination protocol of repeated HAIC-EC and percutaneous intratumoral injection chemotherapy with a mixture of recombinant interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and 5-FU (PIC-IF) in patients with far-advanced HCCs with large APSs or AVSs.

Results

There was a complete response (CR) for the large vascular shunts in all three patients and for all tumor burdens in two patients. Significant side effects were flu-like symptoms (grade 2) and bone marrow suppression (grade 2 or 3) after each cycle, but these were well-tolerated.

Conclusions

These results suggest that the combination of HAIC-EC and PIC-IF is a new and promising approach for advanced HCC accompanied by a large APS or AVS.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Arterioportal shunt, Intratumoral injection chemotherapy, Interferon-gamma

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the 5th most common malignancy worldwide and the 3rd most common cause of cancer mortality.1 Because a majority of patients present at an advanced stage, which does not consistently respond to any chemotherapeutic protocols, the prognosis of HCC is generally very poor. Only a small proportion of cases with HCC diagnosed at an early stage as a result of close surveillance, and with serial imaging studies, could be eligible for and receive curative treatments, such as liver transplantation and surgical resection, resulting in a favorable long-term outcome.2 The Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging classification system, which reflects liver functional status and characteristic features of HCC staging, is a clinically useful algorithm for selecting proper management and predicting the prognosis of HCC patients.2,3

The management of patients with advanced BCLC stages (BCLC stage C) is a complex issue, as the degree of vascular invasion, tumor size and number, extrahepatic metastasis, HCC-associated complications, liver functional reserve, and the performance status of the patient must be taken into account. Systemic chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and transarterial infusion chemotherapy via implantable drug delivery systems rarely offer survival benefits, such as select patients with well-preserved liver function and a good performance status.4 Despite a search for an effective multidisciplinary approach to improve outcomes, no treatment protocol has been developed for patients with advanced BCLC stages and major vascular invasions and/or extrahepatic metastasis.

It was reported that repeated combination treatment of hepatic arterial infusion lipiodol chemotherapy with epirubicin and cisplatin (HAIC-EC) and systemic infusion of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), a modified HAIC-EC/F protocol, could be beneficial with respect to the survival advantage for some patients with advanced HCCs and major portal vein invasion in comparison with control patients treated conservatively.5 Another multimodality approach in which percutaneous ethanol injection therapy (PEIT) is used in addition to the same modified HAIC-EC/F protocol for far advanced HCCs, showed significantly better treatment responses than conventional trans arterial chemoembolization (TACE) using a mixture of lipiodol and adriamycin with gelfoam embolization.6 Multimodality chemotherapeutic approach may be critical in the management of HCC patients with advanced BCLC stage and preserved liver function.

Unlike metastatic liver cancers, far advanced HCCs frequently invade the portal or hepatic veins, sometimes creating vascular shunts with the hepatic artery (arterioportal shunt [APS] or arterio-venous shunt [AVS]), together with the formation of large tumor thrombi. Current treatments have had little effect on the survival of patients with far advanced HCCs with shunts.

In this study, we investigated the efficacy and adverse events of percutaneous intratumoral injection chemotherapy consisting of a mixture of 5-FU and recombinant interferongamma (IFN-γ; PIC-IF) in combination with HAIC-EC in patients far advanced HCCs with shunts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Eligibility

The eligibility criteria for chemotherapy were as follows: (1) 18-75 years of age; (2) preserved liver function (Pugh-Child class A and B); (3) acceptable range of thrombocytopenia due to portal hypertension without any other causes of bone marrow suppression (platelet count>50,000/mm3 and leukocyte count>2,000/mm3); (4) normal serum creatinine (Cr<1.2 mg/dL); (5) acceptable range of hepatitis activity (alanine aminotransferase, [ALT]<100 IU/L); and (6) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (PS) 0-2. The inclusion criteria of far advanced HCC features for the protocol were as follows: (1) TNM stage III or IV by AJCC/UICC or LCSGJ classification; (2) major vascular invasion, such as main portal vein tumor thrombosis or main hepatic vein tumor thrombosis; and (3) marked vascular shunts, such as AVSs or APSs. Patients with HCC with extra-hepatic metastases at the time of initial diagnosis were also included if they had a marked APS or AVS. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) presence of other malignant diseases; (2) history of recent upper gastrointestinal bleeding; (3) sepsis; and (4) serious chronic disorders in other organs. We received informed consent in all patients treated with this protocol, which was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Bundang Jesaeng General Hospital.

Patients

Of the HCC patients admitted to our hospital between March 2003 and December 2009, 4 patients met the inclusion criteria of far advanced HCC. Because one patient is currently undergoing treatment, three of the four patients were assessed retrospectively.

Treatment protocol

The treatment protocol, consisted of one cycle of HAIC-EC on day 1 and PIC-IF on day 2, repeated every 4-6 weeks until efficacy was achieved as defined by the criteria of the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST). The dose of epirubicin (50 mg/m2/session; Il Dong Pharmaceuticals Co. Ltd., Seoul, Korea) and cisplatin (60 mg/m2/session; Dong-A Pharmaceuticals Co. Ltd., Seoul, Korea) for HAIC was adjusted based on age, liver function, and leukocyte count measured just before each treatment cycle. For the dose calculation equation for epirubicin and cisplatin, we used empirical parameters in each variable as follows: calculated dose=(dose per body surface area [BSA])×(leukocyte count/4000)×(1-[Pugh score-5]/10)×(1-[age-45]/100)6; we did not consider the intrahepatic tumor volume parameter for the adjustment of dosage because all HCCs were in the advanced stage. Fixed doses of IFN-γ (2 million units per vial, Intermax-gamma; LG Life Sciences Pharmaceuticals Co. Ltd., Daejeon, Korea) and 5-FU (500 mg per ample; Choong Wae Pharmaceuticals Co. Ltd., Seoul, Korea) were used for PIC to the far advanced HCCs (10 MU and 1500 mg per session, respectively). This cocktail ratio was decided by the maximum efficient combination, which was calculated by HCC cell line experiments.

For HAIC-EC, 1 liter of normal saline was administered intravenously before and after the transarterial angiographic procedure to prevent cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Dolasetron mesylate (200 mg per tab, Anzemet, Sanofi-Aventis; HANDOK Pharmaceuticals Co. Ltd., Seoul, Korea) was used to treat nausea and vomiting following chemotherapy for 4 successive days. Megestrol acetate oral suspension (800 mg per pack, Apetrol; LG Life Sciences Pharmaceuticals Co. Ltd., Daejeon, Korea) was also used to improve appetite and quality of life.

For PIC-IF, IFN-γ (10 million units) and 5-FU (1,500 mg) were mixed well just before injection via a PEIT needle (21 gauge, 200 mm size with 3-7 holes and a closed tip) with an extension tube. Under ultrasonographic guidance, the needle tip was rapidly placed in the target area, which included HCC at the border invading the portal or hepatic veins or the inner mantle portion of the HCC. After which the syringe with the cocktail was injected very slowly over 10 minutes. The fasting state was at least 6 hours, and 50 mg of demerol and hydroxyzine (25 mg per tab, Ucerax; Yuhan Pharmaceuticals Co. Ltd., Seoul, Korea), a sedating antihistamine, was administered 30 minutes before the procedure as a premedication, and propacetamol HCl (1 g per vial, Denogan, Yungjin Pharmaceuticals Co. Ltd, Seoul, Korea), an antipyretic, was administered intravenously for 15 min to treat IFN-γ-induced flu-like reactions, such as fevers, chills and myalgias, immediately following the procedure.

The length of admission was usually from 4-7 days. Laboratory tests were usually performed 3 times during the admission (before and 1 day after treatment, and prior to discharge). Additional laboratory tests were performed from 7-10 days after discharge in the outpatient clinic to evaluate the degree of bone marrow suppression.

Effecacy and adverse reactions

Treatment efficacy according to the RECIST criteria was evaluated after at least two cycles of protocol therapy, and every cycle thereafter. Treatment efficacy was based on changes in the characteristic features of the HCC as shown in clinico-radiologic studies, including an alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level, PIVKA-II, conventional biochemical liver function tests, a triphasic liver CT scan, and a hepatic arteriogram, which were performed during each treatment cycle. The radiologic features included the changes in the number and sizes of tumors, response pattern of vascular thrombosis and occlusion of shunts, together with enhancing patterns around the tumor nodules.

Adverse reactions were assessed during and after each cycle of protocol therapy according to the criteria of the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (NCI-CTC; version 2.0).3

RESULTS

Response and outcome

All three patients, who were AJCC-TNM stage IV, BCLC stage C, and Pugh-Child class A, had an objective response, tumor shrinkage, and disappearance of the APS or AVS. CR to our multimodality protocol, the combination treatment of HAIC-EC and PIC-IF, was obtained in two patients. The disease-free survivals of the two patients with CRs without any evidence of recurrence until the present are 28.6 months and 30.3 months, respectively. One patient had a CR in an intrahepatic HCC lesion, but progressive disease in metastatic lesions (lung and adrenal gland), and died of respiratory failure and septicemia; the survival time was 22.4 months. Each clinical course is described in detail below (Table 1).

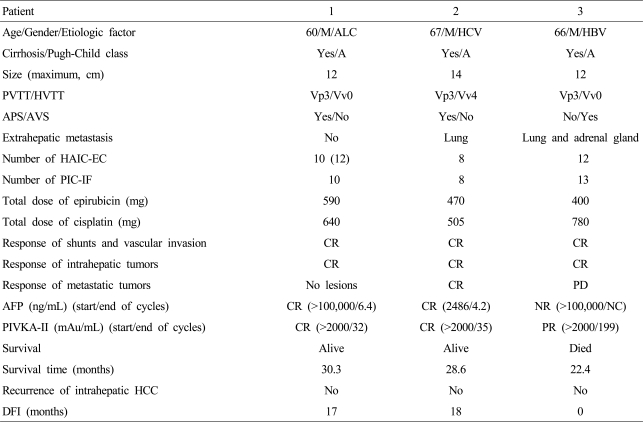

Table 1.

Profiles, responses, and outcomes of three patients with advanced HCC

ALC, alcoholic; PVTT, portal vein tumor thrombosis; HVTT, hepatic vein tumor thrombosis; APS, arterio-venous shunt; AVS, arterio-venous shunt; HAIC-EC, hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy with epirubicin and cisplatin; PIC-IF, percutaneous intratumoral injection chemotherapy with IFN-gamma and 5-FU; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; PD, progressive disease; NR, no response; DFI, disease-free interval.

Patient 1

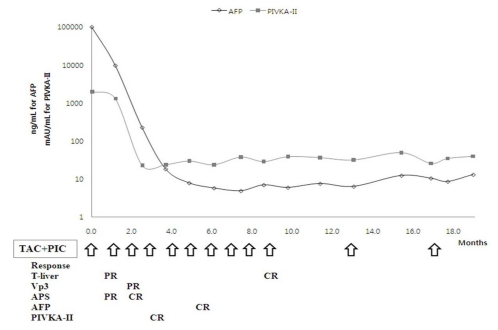

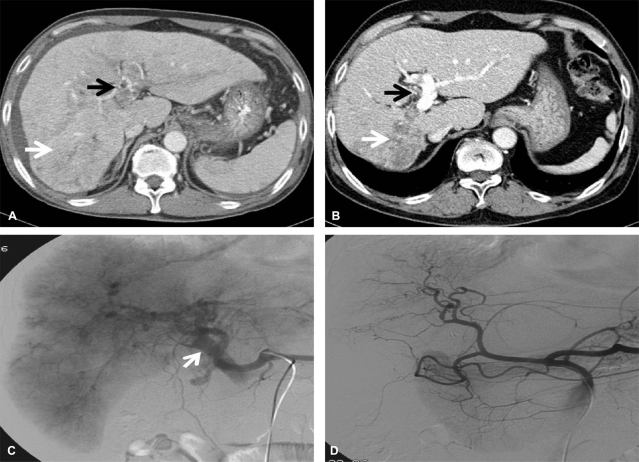

A 60-year-old man was admitted due to variceal bleeding. Dynamic CT scan showed a massive infiltrative type of HCC with a maximum diameter ≥12 cm and the main portal vein tumor thrombosis with a massive APS in the right lobe. The baseline blood tests were as follows: white blood cell count (WBC) 17,100/mm3, hemoglobin 6.2 g/dL, platelet count 217,000/mm3, albumin 2.8 g/dL, total bilirubin 1 mg/dL, prothrombin time-INR 1.2, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 488 IU/L, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 170 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 64 IU/L, total cholesterol 109 mg/dL, creatinine 0.9 mg/dL, AFP and PIVKA-II >100,000 ng/mL and >2,000 mAU/mL respectively. HBsAg and anti-HCV were negative. After recovery from variceal bleeding by ligation therapy, when the liver function reverted to Pugh-Child A without ascites, the protocol therapy of HAIC-EC and PIC-IF was started. This patient had a CR in both serologic HCC biomarkers and radiologic evaluations after 10 cycles of the treatments, and is still alive without any evidence of recurrence for 30 months (disease-free interval [DFI], 17 months) (Fig. 1, 2).

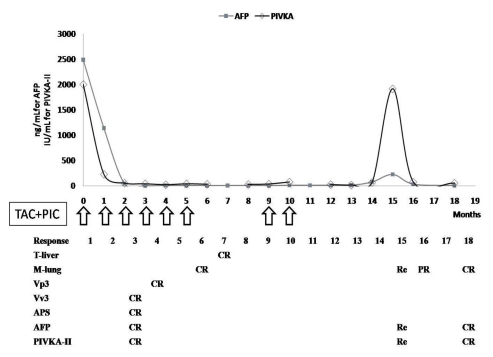

Figure 1.

Clinical response and changes in tumor markers after combination treatment with HAIC-EC and PIC-IF in patient 1. Complete remission of HCC was achieved after 10 cycles of treatment. HAIC-EC, hepatic arterial infusion (lipiodol) chemotherapy with epirubicin and cisplatin; PIC-IF, percutaneous intratumoral injection chemotherapy with a mixture of IFN-γ and 5-FU; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

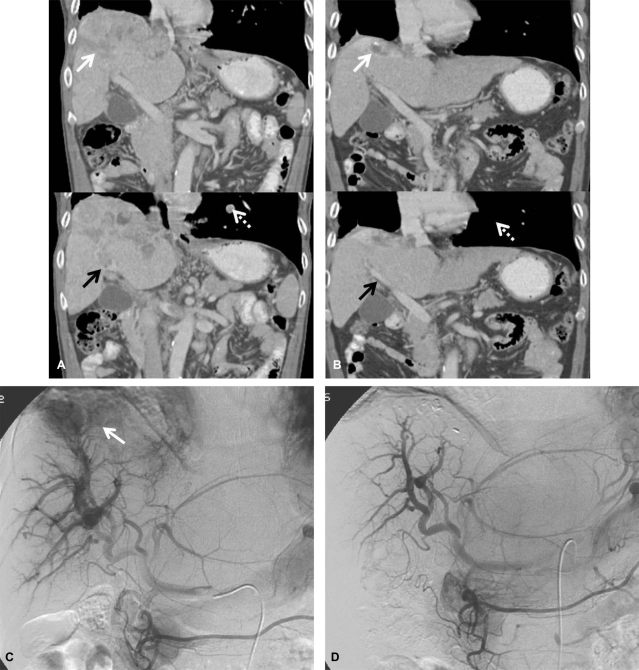

Figure 2.

Dynamic CT (A, before treatment; B, after treatment) scans showing the response to the treatment protocol in patient 1. Diffuse tumor thrombosis along the entire intrahepatic portal vein system (black arrow) and massive infiltrative type HCC lesion were markedly regressed (white arrow). Hepatic arteriography (C, before treatment; D, after treatment) showing a huge hypervascular mass with a large APS before treatment (arrow). Complete remission of both intrahepatic HCC lesions and massive APS was achieved after 10 cycles of treatment.

Patient 2

A 67-year-old man, who had experienced exertional dyspnea and chest discomfort for 1 month, was admitted for the treatment of advanced HCC. At the time of the initial evaluation, a dynamic CT scan showed a massive infiltrating HCC with a maximum diameter of 14 cm occupying the right lobe with extensive tumor thrombosis in the right hepatic vein, inferior vena cava, and right atrium, and the main portal vein tumor thrombosis with a massive APS. Multiple metastases were observed in both lung fields. The initial laboratory test showed the following: hemoglobin 15 g/dL, WBC 5,300/mm3, platelet 94,000/mm3, albumin 3.9 g/dL, total bilirubin 1.45 mg/dL, prothrombin time-INR 1.18, ALP 1,951 IU/L, AST 118 IU/L, ALT 48 IU/L, total cholesterol 86 mg/dL, AFP and PIVKA-II 2,486 ng/mL and >2000 AU/mL, respectively. HBsAg was negative, and anti-HCV was positive, however quantitative HCV RNA (Cobas Amplicor HCV Monitor 2.0®; Roche Diagnostics, Branchburg, NJ, USA) was negative. Soon after the protocol therapy, together with an improvement in symptoms, the patient showed objective responses in all lesions, including the intrahepatic HCC lesions, vascular invasion, and pulmonary metastases (Fig. 3, 4). During the follow-up, the AFP and PIVKA-II levels were elevated without any disease progression evident on radiologic evaluations. After the oral administration of tegafur and uracil (tegafur [100 mg], uracil [224 mg per 0.5 g pack], UFT-E granules, Jeil Pharmaceuticals Co. Ltd, Seoul Korea), both serological HCC biomarkers normalized again (Fig. 3). The patient is alive without any evidence of recurrence after 28 months (DFI, 18 months).

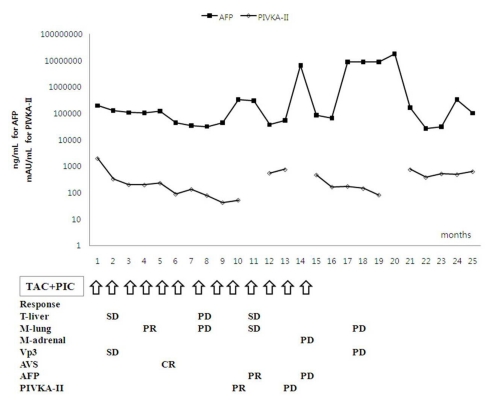

Figure 3.

Clinical response and changes in tumor markers after combination treatment with HAIC-EC and PIC-IF in patient 2. Complete remission of intrahepatic HCC with a large shunt and pulmonary metastasis was achieved after six cycles of treatment. Elevation of tumor marker levels was observed without any radiologic evidence of recurrence. The serologic HCC biomarkers normalized after the oral administration of tegafur and uracil.

Figure 4.

Dynamic CT (A, before treatment; B, after treatment) scans showing the response to the treatment protocol in patient 2. An ill-defined huge mass mainly involving the right lobe (white arrow) and tumor thrombosis along the right portal system (black arrow) and inferior vena cava were markedly decreased after treatment. Pulmonary metastatic lesions had also completely disappeared (dotted arrow). Hepatic arteriography (C, before treatment; D, after treatment) showed an ill-defined huge mass mainly involving the right lobe and tumor thrombosis along the right portal system and inferior vena cava, together with a large APS at the time of initial treatment. All of the lesions had markedly improved after the treatment.

Patient 3

A 66-year-old man who had anorexia and nausea for 1 month was found to have liver cirrhosis and far advanced HCC during an evaluation. The initial dynamic CT scan showed a massive infiltrating HCC with a maximum diameter of 12 cm occupying the right lobe, and complicated by a turmor thrombosis in the main hepatic vein with a large AVS. Small pulmonary metastatic lesions were also identified. The initial laboratory tests were as follows: hemoglobin 15.7 g/dL, WBC 5,000/mm3, platelet 128,000/mm3, albumin, 4.1 g/dL, total bilirubin 1.0 mg/dL, prothrombin time-INR 1.21, ALP 254 IU/L, AST 242 IU/L, ALT 60 IU/L, total cholesterol 190 mg/dL, AFP and PIVKA-II 192,320 ng/mL and >2000 AU/mL, respectively. HBsAg was positive, HBeAg and HBV DNA (Amplicor HBV Monitor®; Roche Molecular System, Pleasanton, CA, USA) were negative, and anti-HCV was negative. After the protocol therapy, together with the improvement in symptoms, the patient showed objective responses completely in the intra- hepatic HCC lesions, vascular invasion, and AVS by radiologic evaluations, and also partial improvement in the extra-hepatic lesions based on AFP and PIVKA-II tests (Fig. 5, 6). However, on serial testing, the levels of serologic HCC biomarkers rose again, and multiple metastases to both lung fields and the right adrenal gland occurred rapidly, in spite of repeated courses of chemotherapy (Fig. 5). The patient died of respiratory failure with septicemia 22 months after registration.

Figure 5.

Clinical response and changes in tumor markers after combination treatment with HAIC-EC and PIC-IF in patient 3. Intrahepatic HCC lesions with a large AVS showed a complete response to the treatment protocol, but extrahepatic metastatic lesions showed only a partial response early in the treatment course. However, elevation of the AFP and PIVKA-II levels and multiple metastases in both lungs and adrenal gland were aggravated without intrahepatic recurrence of HCC late in the treatment course.

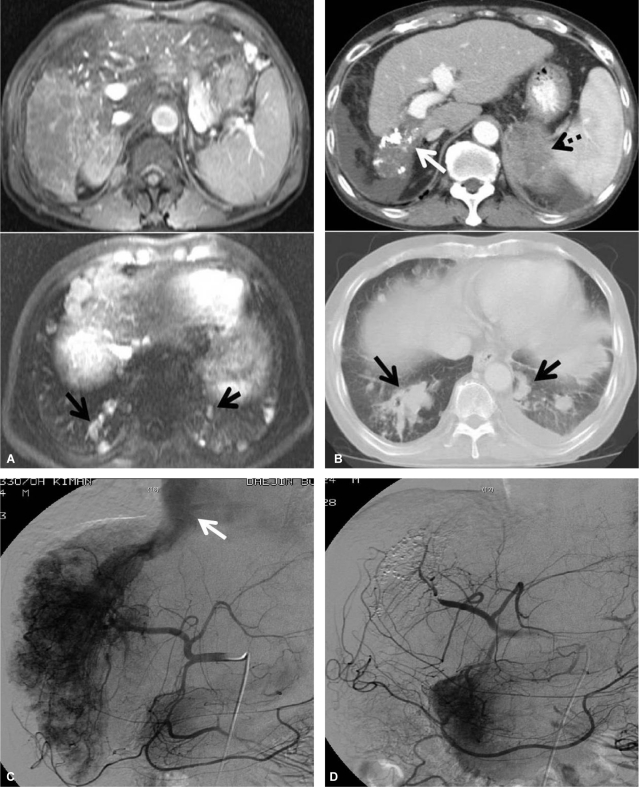

Figure 6.

MRI and dynamic CT (A, before treatment; B, after treatment) scans showing the response to the treatment protocol in patient 3. A massive HCC in the right hepatic lobe with right portal vein invasion and multiple lung metastases were noted, but initial MRI revealed no lesions in the adrenal gland. After the treatment protocol the intrahepatic tumor lesions were markedly improved (white arrow), but the left adrenal metastasis (dotted arrow) and pulmonary metastatic nodules (black arrow) were aggravated. Hepatic arteriography (C, before treatment; D, after treatment) showed a huge hypervascular HCC in the right hepatic lobe and a large AVS (white arrow). Both the HCC lesion and AVS shunt had disappeared after the treatment protocol.

Adverse events

HAIC-EC-associated side effects were observed in all 3 patients (NCI-CTC grade 1 or 2 grade nausea developed during the admission period and grade 2 or 3 leucopenia developed 7-10 days after discharge). PIC-IF-associated side effects were observed in all 3 patients (grade 2 or 3 flu-like symptoms developed 20-30 minutes after the procedure). All side effects were transient and well-tolerated. However, there was a tendency for the degree of bone marrow suppression to be progressively aggravated by the repeated treatments, but no greater than toxicity grade 3. Neither NCI-CTC grade 4 complications nor deterioration in liver and/or renal function developed during repeat protocol therapy.

DISCUSSION

In patients with far advanced HCC complicated by major portal vein tumor thrombosis, the prognosis is dismal, and if not treated, the overall survival is 3.5 months.5 Even if treated aggressively by various protocols of hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy using a combination of 5-FU and cisplatin, the objective response rates are about 20% without any CRs; the median survival of patients with objective response is only 8-14 months, and the 2-year survival is ≤ 25%.7,8 This survival is much shorter than that of the entire HCC cohort, in which the 1-and 3-year survival is 58% and 29%, respectively.3 A chemotherapy protocol using combined transarterial epirubicin (50 mg/m2) plus cisplatin (60 mg/m2) chemo-lipiodolization and systemic 5-FU (200 mg/m2) chemo-infusion (ECF regimen) at monthly intervals also showed similar results to the combination protocol of 5-FU and cisplatin, although significantly better than the patients treated conservatively (objective response, 21.3%; and overall survival, 8.7 months).5 These findings suggest that major occlusion of the portal vein invaded by HCC determines resistance to treatment as well as decreased liver function, increased MELD score, and poor performance status. Together with portal vein tumor thrombosis, the occurrence of APS or AVS thwarts the strength of will for further treatment of HCC.

However, advances in techniques have made it possible to approach the treatment of HCC patients with complicated findings. For example, transarterial embolization (TAE) using steel coils successfully treated 3 patients with HCC with massive APS.9 TACE during the corresponding portal vein occlusion in HCC patients with marked APS also showed better treatment responses than shunt embolization with the use of coils and/or gelatin-sponge particles.10

In the current study we developed a new multimodal protocol of PIC-IF in combination with HAIC-EC for the treatment of advanced HCCs. A key component in this protocol is the direct injection of a cocktail of IFN-γ and 5-FU into the marginal part of the tumor by the same technique as PEIT, by which parts of cancer cells are transiently exposed to very high concentrations of an anticancer cocktail. Such intratumoral injection of chemotherapeutic agents can provide a high concentration of drug to the tumors much more conveniently and effectively than intra-arterial infusion while reducing systemic exposure. The intratumoral injection method has been more frequently adapted in antitumor immunotherapy studies to induce immunologic responses locoregionally. Intratumoral injection of recombinant interleukin-12 induces very high concentration of IFN-γ from tumor-infiltrating Th1 cells.11

IFN-γ-inducible protein 10 (IP-10), a potent inhibitor of tumor angiogenesis, in combination with gemcitabine has synergistic effects on tumors by inhibiting the proliferation of endothelial cells, inducing the apoptosis of tumor cells, and recruiting lymphocytes to tumors in murine models.12 Otherwise, CD4(+) T cells play a pivotal role in controlling early tumor development through inhibition of tumor angiogenesis which is IFN-γ-dependent. IFN-γ-dependent inhibition of tumor angiogenesis by CD4(+) T cells requires tumor responsiveness to IFN-γ.13

Because non-responders to chemotherapy usually have a significantly higher percentage of Th2 cells, which down-regulate antitumor immunity, than the responders both before and after chemotherapy, inhibition of an increase of Th2 cells might be important for the efficacy of transarterial combination chemotherapy in advanced HCCs with cirrhosis.14 We reasoned that locoregional adjuvant injection of recombinant IFN-γ might modulate Th1/Th2 balance of the tumor to favor an anti-tumor response.

Furthermore, IFN-γ synergistically enhances anti-cancer efficacy of chemotherapeutic agents, such as 5-FU, mitomycin-C and cisplatin.15,16 Suggested mechanisms are the inhibition of MDR P-glycoprotein expression and up-regulation of caspase-8.17,18 As another mechanism, while HBV expression in HCC cell lines shows drug resistance against 5-FU, IFN-γ treatment modulates this type of chemoresistance to be more chemosensitive by inhibition of HBV-related NF-kappa B activation.19

In our protocol, an anti-cancer cocktail consisting of IFN-γ and 5-FU was injected directly into the periphery of the tumor and/or a root part of the vascular invasion, under the assumption that 5-FU modulates IFN receptor expression,20 and locoregional IFN-γ plays a pivotal role in establishing the anti-tumor immune response and additive effects of chemotherapeutic agents. Although our study included only three patients, the results suggest the possibility that this type of multimodal protocol therapy may be a promising approach to the treatment of advanced HCCs with or without vascular invasions or large shunts.

Abbreviations

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- APS

arterio-portal shunt

- AVS

arterio-venous shunt

- TACE

transarterial lipiodol chemoembolization

- HAIC-EC

hepatic arterial infusion (lipiodol) chemotherapy with epirubicin and cisplatin

- RFA

radiofrequency ablation

- PEIT

percutaneous ethanol injection therapy

- PIC

percutaneous intratumoral injection chemotherapy

- IFN-γ

recombinant interferon-gamma

- 5-FU

5-fluorouracil

- PIC-IF

PIC with a mixture of IFN-γ and 5-FU

- BCLC

Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer

- DFI

disease-free interval

- LCSGJ

Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan

References

- 1.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Estimating the world cancer burden: Globocan 2000. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:153–156. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuo YH, Lu SN, Chen CL, Cheng YF, Lin CY, Hung CH, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance and appropriate treatment options improve survival for patients with liver cirrhosis. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:744–751. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marrero JA, Fontana RJ, Barrat A, Askari F, Conjeevaram HS, Su GL, et al. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison of 7 staging systems in an American cohort. Hepatology. 2005;41:707–716. doi: 10.1002/hep.20636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang JH, Changchien CS, Hu TH, Lee CM, Kee KM, Lin CY, et al. The efficacy of treatment schedules according to Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging for hepatocellular carcinoma-Survival analysis of 3892 patients. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:1000–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jang JW, Bae SH, Choi JY, Oh HJ, Kim MS, Lee SY, et al. A combination therapy with transarterial chemo-lipiodolization and systemic chemo-infusion for large extensive hepatocellular carcinoma invading portal vein in comparison with conservative management. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2007;59:9–15. doi: 10.1007/s00280-006-0239-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jang JW, Park YM, Bae SH, Choi JY, Yoon SK, Chang UI, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of multimodal combination therapy using transcatheter arterial infusion of epirubicin and cisplatin, systemic infusion of 5-fluorouracil, and additional percutaneous ethanol injection for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2004;54:415–420. doi: 10.1007/s00280-004-0829-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eun JR, Lee HJ, Moon HJ, Kim TN, Kim JW, Chang JC. Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy using high-dose 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin with or without interferon-alpha for the treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombosis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:1477–1486. doi: 10.3109/00365520903367262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woo HY, Bae SH, Park JY, Han KH, Chun HJ, Choi BG, et al. A randomized comparative study of high-dose and low-dose hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy for intractable, advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2010;65:373–382. doi: 10.1007/s00280-009-1126-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hiyoshi Y, Beppu T, Okabe K, Hayashi H, Masuda T, Okabe H, et al. The efficacy of transcatheter embolization of severe arterioportal shunts in hepatocellular carcinoma. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2007;34:2093–2095. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murata S, Tajima H, Nakazawa K, Onozawa S, Kumita S, Nomura K. Initial experience of transcatheter arterial chemoembolization during portal vein occlusion for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma with marked arterioportal shunts. Eur Radiol. 2009;19:2016–2023. doi: 10.1007/s00330-009-1349-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Herpen CM, Looman M, Zonneveld M, Scharenborg N, de Wilde PC, van de Locht L, et al. Intratumoral administration of recombinant human interleukin 12 in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma patients elicits a T-helper 1 profile in the locoregional lymph nodes. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:2626–2635. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mei K, Wang L, Tian L, Yu J, Zhang Z, Wei Y. Antitumor efficacy of combination of interferon-gamma-inducible protein 10 gene with gemcitabine, a study in murine model. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2008;27:63. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-27-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beatty G, Paterson Y. IFN-gamma-dependent inhibition of tumor angiogenesis by tumor-infiltrating CD4+ T cells requires tumor responsiveness to IFN-gamma. J Immunol. 2001;166:2276–2282. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagai H, Miyaki D, Matsui T, Kanayama M, Higami K, Momiyama K, et al. Th1/Th2 balance: an important indicator of efficacy for intra-arterial chemotherapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;62:959–963. doi: 10.1007/s00280-008-0685-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klein HO, Golbach G, Voigt P, Coerper C, Bernhardt C. Combination of interferons and cytostatic drugs for treatment of advanced colorectal cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1991;117(Suppl 4):S214–S220. doi: 10.1007/BF01613230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirabayashi N, Yoshinaka K, Nosoh Y, Toge T, Niimoto M, Hattori T, et al. In vitro chemosensitivity tests on human tumor xenografts by clonogenic assay: the combined use of mitomycin C with alpha-interferon or gamma-interferon. Jpn J Surg. 1985;15:279–284. doi: 10.1007/BF02469918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manara MC, Serra M, Benini S, Picci P, Scotlandi K. Effectiveness of Type I interferons in the treatment of multidrug resistant osteosarcoma cells. Int J Oncol. 2004;24:365–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lissat A, Vraetz T, Tsokos M, Klein R, Braun M, Koutelia N, et al. Interferon-gamma sensitizes resistant Ewing\'s sarcoma cells to tumor necrosis factor apoptosis-inducing ligand-induced apoptosis by up-regulation of caspase-8 without altering chemosensitivity. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:1917–1930. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chung C, Park SG, Park YM, Joh JW, Jung G. Interferon-gamma sensitizes hepatitis B virus-expressing hepatocarcinoma cells to 5-fluorouracil through inhibition of hepatitis B virus-mediated nuclear factor-kappaB activation. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:1758–1766. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00591.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oie S, Ono M, Yano H, Maruyama Y, Terada T, Yamada Y, et al. The up-regulation of type I interferon receptor gene plays a key role in hepatocellular carcinoma cells in the synergistic antiproliferative effect by 5-fluorouracil and interferon-alpha. Int J Oncol. 2006;29:1469–1478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]