Abstract

Background/Aims

We investigated the frequency of occult hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in anti-hepatitis C virus (HCV)-positive individuals and the effects of occult HBV infection on the severity of liver disease.

Methods

Seventy-one hepatitis B virus surface-antigen (HBsAg)-negative patients were divided according to their HBV serological status into groups A (anti-HBc positive, anti-HBs negative; n=18), B (anti-HBc positive, anti-HBs positive; n=34), and C (anti-HBc negative, anti-HBs positive/negative; n=19), and by anti-HCV positivity (anti-HCV positive; n=32 vs. anti-HCV negative; n=39). Liver biopsy samples were taken, and HBV DNA was quantified by real-time PCR.

Results

Intrahepatic HBV DNA was detected in 32.4% (23/71) of the entire cohort, and HBV DNA levels were invariably low in the different groups. Occult HBV infection was detected more frequently in the anti-HBc-positive patients. Intrahepatic HBV DNA was detected in 28.1% (9/32) of the anti-HCV-positive and 35.9% (14/39) of the anti-HCV-negative subjects. The HCV genotype did not affect the detection rate of intrahepatic HBV DNA. In anti-HCV-positive cases, occult HBV infection did not affect liver disease severity.

Conclusions

Low levels of intrahepatic HBV DNA were detected frequently in both HBsAg-negative and anti-HCV-positive cases. However, the frequency of occult HBV infection was not affected by the presence of hepatitis C, and occult HBV infection did not have a significant effect on the disease severity of hepatitis C.

Keywords: Occult infection, Hepatitis B virus, Hepatitis C virus, HBV DNA

INTRODUCTION

Occult hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is defined as the presence of low HBV DNA levels in the blood, liver tissue, or peripheral monocytes of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)-negative persons.1,2 It has been reported that in individuals with occult HBV infection, the DNA level in peripheral blood is usually fewer than 103 copies/mL and as low as 1,000 copies per 1 µg of DNA extracted from liver tissue.3-5 Advances in detection technologies in the past decade have allowed greater insight into occult HBV infection.

Occult HBV infection is divided into seropositive (anti-HBc (IgG) positive), and seronegative (anti-HBc (IgG) negative) cases. It has been reported that the rate of occult infection is higher in seropositive cases. Additionally, the rate of occult HBV infection is higher in areas of high HBV prevalence6 and in those with hepatitis C virus (HCV) or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.7-9 Recent data showed that occult HBV infection was detected in 37 (41.6%) of the 89 patients with biopsy proven chronic hepatitis C.10 However, reported frequencies of occult infection vary considerably, probably due to a lack of standardized diagnostic protocols; this results in different diagnoses being obtained from similar or identical samples.

In acute hepatitis B, disappearance of HBsAg indicates clearance of the virus and, thus, the absence of hepatitis. However, even after the disappearance of HBsAg and appearance of anti-HBs, low-level viremia may persist.11 Indeed, HBV DNA has been detected in liver tissue after a lapse of several years.12,13 Detectable serum HBsAg is absent in around 0.51% of chronic HBV carriers14; however, in most cases HBV DNA is detectable in liver tissue even after the disappearance of HBsAg from the blood.15 Thus, the power of an HBsAg test alone to determine HBV carrier status is limited.

It remains controversial as to whether HBV occult infection has any clinical significance. However, several reports suggest the clinical relevance of occult HBV infection: its contagiousness, reactivation of occult HBV infection, linkage of occult HBV infection to chronic liver diseases and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and, finally, its potential effect on the progression of liver disease.2

In this study, the frequency of occult HBV infection in the liver tissue of anti-HCV positive patients was studied, and the effect of occult HBV infection on the severity of hepatitis C disease were investigated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

This study included 71 subjects with chronic liver disease who were HBsAg negative. We performed liver biopsy for the diagnosis of underlying liver disease. Of them, 18 were anti-HBs-negative and anti-HBc-positive, and 34 were anti-HBc-positive and anti-HBs-positive. The remaining 19 were anti-HBc-negative, of which 10 were anti-HBs-positive and nine were anti-HBs-negative (Table 1). Among the 71 subjects, there were 32 cases of chronic hepatitis C or HCV-related liver cirrhosis (LC) (including seven of HCC), six cases of metastatic liver cancer, six cases of alcoholic liver disease, six cases of autoimmune hepatitis, six cases of liver abscess, including inflammatory pseudotumor, four cases of peripheral cholangiocarcinoma and three cases of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Of the remaining eight, two each had primary biliary cirrhosis and eosinophilic liver abscess and one each had hemangioma and focal nodular hyperplasia. To examine the correlation between blood and intrahepatic HBV DNA levels, we measured HBV DNA concentrations in liver tissue in six HBsAg-positive cases with varying serum HBV DNA concentrations.

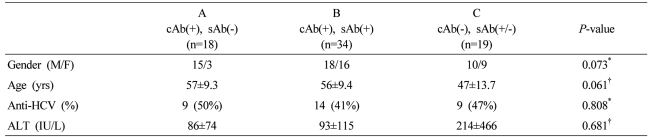

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the patients according to the serologic HBV status

Statistical significance test was done by Chi-square test* and Kruskal Wallis test†.

cAb, anti-HBc (IgG) antibody; sAb, anti-HBs antibody; HCV, hepatitis C virus; ALT, alanine aminotransferase.

Methods

Serum HBsAg and anti-HBc (IgG) was measured using the HBsAg Kit® and the Anti-HBc Kit® (Beijing North Institute of Biological Technology, Beijing, China), and anti-HBs was measured by the radioimmunoassay method using the Hepatitis B surface antigen 125I (human subtypes ad and ay) AUSAB® kit (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, USA).

Liver biopsies were conducted using the ACECUT® Automatic Biopsy System (TSK laboratory, Tochigi-Ken, Japan). We used an 18-gauge diameter needle and collected 5-mg specimens 15 mm in length. Biopsies were stored at below -70℃ until required. Specimens were sent for histopathological assessment by the Pathology Department. Intrahepatic HBV DNA was extracted using a QIAamp® DNA Micro Kit (Qiagen Gmbh, Germany). Extracted HBV DNA was quantified by the real-time PCR method, using a LightCycler® instrument (Roche Diagnostics, Germany) and RealArt™ HBV LC PCR reagent (Artus, Germany). According to the manufacturer, the assay detection limit was 3.5 IU/mL (18 copies/mL) and its specificity was assessed using a panel of 100 HBV-negative serum samples. Intrahepatic HBV DNA concentration was expressed as the number of viral DNA copies per 1 mg liver tissue. To verify the reliability of intrahepatic HBV DNA quantification, we measured the blood HBV DNA concentration of six HBsAg-positive cases using a Cobas Amplicor HBV Monitor™ kit (Roche Molecular Systems, Pleasanton, CA, USA) and examined its correlation with the intrahepatic concentration. This study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board and was conducted in accordance with the principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki.

We classified pathological findings on chronic hepatitis in patients with chronic hepatitis C into minimal, mild, moderate, and severe chronic hepatitis, according to Scheuer's scoring system,16 and assessed the effect of occult HBV infection of hepatitis C disease severity.

Statistics

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation, or n (%) as appropriate. When comparing the baseline characteristics of patients between different groups, chi-square test and Fisher's exact test were used for categorical data, and the Student t test, Mann-Whitney U-test and Kruskal-Wallis test were used for continuos variables. Spearman's correlation was used in this study. Data were analyzed using the SPSS software (ver. 11.0). The base significance level was set at P<0.05.

RESULTS

Detection of intrahepatic HBV DNA according to HBV serological status

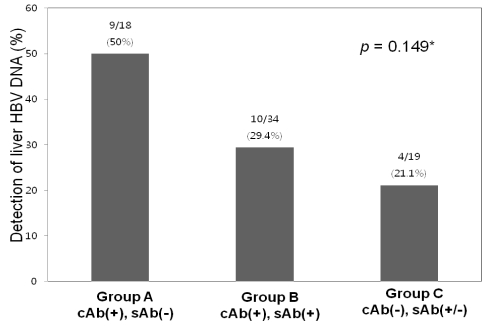

Intrahepatic HBV DNA was detected in 23 of the 71 (32.4%) HBsAg-negative subjects. HBV DNA detection frequency was highest (9/18; 50%) in the anti-HBc (+) anti-HBs (-) group, and was detected in 10/34 (29.4%) of anti-HBc (+) anti-HBs (+) cases. Therefore, intrahepatic HBV DNA was detected in 19/52 (36.5%) of anti-HBc-positive subjects regardless of anti-HBs status (Fig. 1). In the anti-HBc-negative group, intrahepatic HBV DNA was detected in 4/19 (21.1%) of subjects. Detection frequencies were not significantly different among these groups (P=0.149).

Figure 1.

The overall frequency of detection of intrahepatic HBV DNA was 32.4% in all of the specimens and 36.5% in anti-HBc-positive subjects. The frequency of intrahepatic HBV DNA detection did not differ significantly between the three groups. The frequency was highest (50%) in group A, followed by 29.4% in group B and 21.1% in group C. *Statistically significant when P<0.05 (Chi-square test).

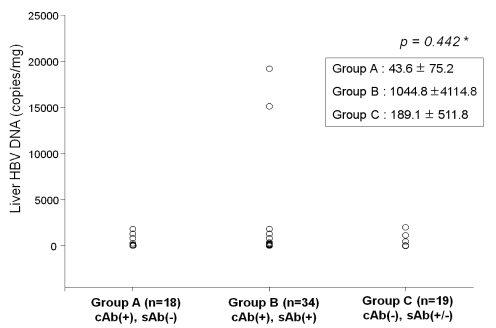

Intrahepatic HBV DNA concentrations were 43.6±75.2, 1044.8±4224.8 and 189.1±511.8 copies/mg in the anti-HBc (+) anti-HBs (-), anti-HBc (+) anti-HBs (+) and anti-HBc (-) groups, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference between them (P=0.442) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

HBV DNA levels were low in all subjects and did not differ significantly with anti-HBc or anti-HBs status. *Statistically significant when P<0.05 (Kruskal-Wallis test).

Detection of intrahepatic HBV DNA according to the presence of anti-HCV

Intrahepatic HBV DNA was detected in 9/32 (28.1%) of anti-HCV-positive subjects and 14/39 (35.9%) of others, suggesting that occult HBV infection was not more common in anti-HCV positive patients (Table 2). HCV genotype did not affect the detection rate of intrahepatic HBV DNA (Genotype I (40%) vs. II (25%) (P=0.656).

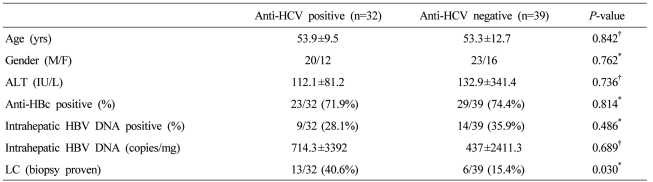

Table 2.

Characteristics of the patients according to anti-HCV positivity

Statistical significance test was done by Chi-square test* and t-test†.

HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; ALT; alanine aminotransferase; LC, liver cirrhosis.

Occult HBV infection and liver disease severity in anti-HCV positive patients

Intrahepatic HBV DNA was detected in 9 anti-HCV positive patients. We divided the 32 anti-HCV-positive individuals into 2 groups according to the presence of intrahepatic HBV DNA, and compared gender, age, serum ALT, histological activity and the frequency of primary liver cancer between the two groups. The mean fibrosis score was 3.6 in intrahepatic HBV DNA-positive and 3.2 in intrahepatic HBV DNA-negative subjects (P=0.263). The frequency of LC and HCC were not significantly different between the two groups (LC, P=0.427; HCC, P=1.000) (Table 3).

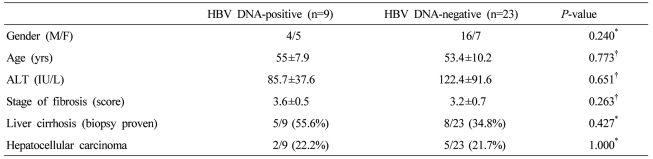

Table 3.

Characteristics of anti-HCV-positive subjects according to intrahepatic HBV DNA positivity

Statistical significance test was done by Chi-square test* and Mann-Whitney U-test†.

HBV, hepatitis B virus; ALT, alanine aminotransferase.

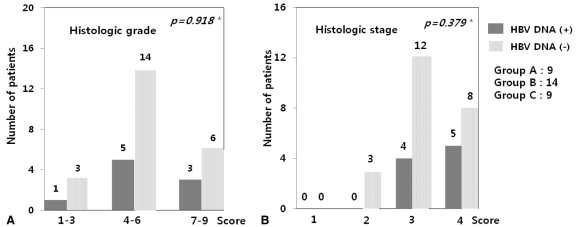

We compared the hepatic histological activities of the 32 cases of chronic hepatitis C according to the detection of intrahepatic HBV DNA. When they were divided into mild (1-3 point), moderate (4-6), and severe (7-9) groups, no significant difference was observed in the detection frequency of intrahepatic HBV DNA between them (P=0.918). The detection frequency of intrahepatic HBV DNA was not different according to the fibrosis (P=0.379) (Fig. 3). Gender, age, and serum ALT were not significantly different.

Figure 3.

Histologic grade or stage scores did not differ significantly with HCV status (i.e., HBV DNA-positive vs. -negative). *Statistically significant when P<0.05 (Chi-square test).

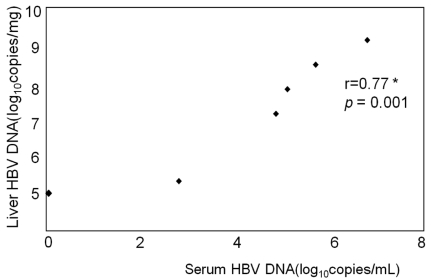

Correlation of intrahepatic and serum HBV DNA concentrations of HBsAg-positive subjects

We used six HBsAg-positive subjects as positive control. In these subjects, blood HBV DNA concentrations varied from negative (below 18 copies/mL) to 1.98×107 copies/mL. Intrahepatic HBV DNA was detected in all six subjects at concentrations that varied between 105 to 109 copies/mg. Additionally, intrahepatic HBV DNA concentrations were closely correlated with those in blood (r=0.77, P=0.001) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Correlation between intrahepatic HBV DNA and serum HBV DNA in six HBsAg-positive subjects. *Correlation coefficients; Spearman's correlation.

DISCUSSION

The frequency of occult HBV infection may differ geographically, depending on HBV prevalence. Reported occult HBV infection frequencies have been as high as 70-90% of anti-HBc-positive individuals in areas of high prevalence but as low as 5-20% in areas of low prevalence.17 A large percentage of anti-HBc-positive Koreans are presumed to have been infected. However, the prevalence of occult HBV infection was reported relatively low (0.7% in HBsAg-negative cases, 1.7% in anti-HBc alone positive cases)18,19 compared to our data. Indeed, in this study, intrahepatic HBV DNA was detected in 36.5% of anti-HBc-positive cases, showing that occult infection is not rare.

The frequency of occult HBV infection differed according to which subjects received the test. It was reported that the frequency of occult HBV infection was as high as 30% when the subjects were patients with a chronic liver disease of unknown cause.20 This suggests that occult HBV infection alone may cause pathological disorders. It is also known that occult HBV infection is frequent in those with chronic hepatitis C. The frequency varies from 30 to 50%.21-24 In another report, HBV DNA was detected in 90% of tested liver tissues.25 This is probably because the route of transmission of hepatitis B and C is similar. In the present study, intrahepatic HBV DNA was detected in 9/32 (28.1%) of anti-HCV-positive and 14/39 (35.9%) of anti-HCV-negative subjects. This differs from the previous reports. Thus, anti-HCV serum status was apparently not related with the presence of occult HBV infection in this study.

Additionally, it has been reported that liver cirrhosis in chronic hepatitis C patients is more common in those with occult HBV infection22 and that their serum ALT levels and histological activity are high.24,26 This suggests the possibility that occult HBV infection is synergistic with chronic hepatitis C in terms of development of liver disease. Moreover, it has been reported that in patients with primary liver cancer caused by HCV infection, the anti-HBc-positive rate was 69.6%, higher than the 38.2% in anti-HBc-negative chronic hepatitis C patients.27 This suggests that if occult HBV infection accompanies chronic hepatitis C infection, the risk of liver cancer may increase. These data confirm reports that most HBsAg- and anti-HCV-negative primary liver cancer patients are anti-HBc-positive28 and that intrahepatic HBV DNA is detected in most of these individuals.29

On the other hand, some studies have reported no difference in serum ALT levels, histological inflammatory activity, or degree of fibrosis between patients with chronic hepatitis C accompanied by occult HBV infection and those infected with HCV alone.29 In this study, intrahepatic HBV DNA was detected somewhat more frequently in chronic hepatitis C patients with F4 fibrosis, but the result was not statistically significant. Furthermore, no significant difference was observed in gender, age, serum ALT, degree of liver fibrosis, frequency of liver cirrhosis, or primary liver cancer whether occult HBV infection was present or not. It will be necessary to perform larger studies on the frequency of HBV occult infection in chronic hepatitis C patients to determine its effect on development of chronic hepatitis C or primary liver cancers.

Blood HBV DNA concentration in HBsAg-positive subjects was high (104 to 108 copies/mL), but in those with occult HBV infection patients it was below 102 copies/mL3. This suggests that many occult HBV infection patients would be serum PCR-negative. As such, use of liver tissue (as in the present study) may be more helpful in detecting occult HBV infection. According to one report, intrahepatic HBV DNA was detected in 37/98 (37.7%) of serum HBV DNA-negative cases by PCR.30 In individuals with occult HBV infection, HBV DNA levels can be low even in liver tissue, 0.01-0.1 copy per cell, according to one study.4 Cacciola et al5 reported average HBV DNA levels of 34,500 copies per 1 µg DNA extracted from liver tissue in patients with active HBV proliferation, but as low as 7,450 and 224 copies in healthy HBsAg carriers and those with HBV occult infection, respectively. This is similar to the data reported here. We detected HBV DNA levels of 43.6±75.2, 1044.8±4224.8, and 189.1±511.8 copies/mg in the anti-HBc positive/anti-HBs negative, anti-HBc positive/anti-HBs positive, and anti-HBc negative groups, respectively. Thus, much lower concentrations were detected in those with occult HBV infection. On the other hand, because viruses may not be distributed evenly in the liver of those with occult infection, careful attention is required in interpreting PCR-negative results.7 Additionally, to overcome the problem of false positivity, diagnosis of occult infection requires a PCR reaction with two primer sets.7

The reason for the increasing interest in occult HBV infection is the increasing evidence of its clinical relevance. This can be divided into four categories: contagiousness of occult HBV infection, reactivation of occult HBV infection, its link to chronic liver diseases, and its link to hepatocellular carcinoma.2

It is well-known that HBV infection can be excluded in anti-HBc-negative individuals, but in the present study, interestingly, intrahepatic HBV DNA was detected in some anti-HBc-negative subjects. In such cases, the possibility of false positivity may need to be considered, but according to one report,31 hepatitis occurred after transplantation in 50% of patients who received livers from anti-HBc-positive donors and as well as in 1.7% of patients who received livers from anti-HBc-negative donors. Transmission may occur through intraoperative transfusion, but this result suggests the possibility that occult HBV infection may be present in anti-HBc-negative subjects. Additionally, in anti-HBc-negative subjects, intrahepatic HBV DNA has been detected in 20% of anti-HCV-positive cases and 12% of anti-HCV negative cases.21 Although it is unclear how anti-HBc appears negative in those with HBV infection, it is possible that anti-HBc is undetectable due to low serum antibody concentrations or that anti-HBc is not produced because HBV core protein is not expressed, due to genetic variation.32 Another possibility is that hepatocytes are infected with such a small number of viruses that an anti-HBc antibody reaction is not induced.23

In conclusion, this study found that intrahepatic HBV DNA was commonly detectable in HBsAg-negative subjects, and that a positive anti-HBc reaction is an important factor related to occult HBV infection. However, the frequency of occult HBV infection was not affected by chronic hepatitis C infection, and the effect of occult HBV infection on the disease severity of hepatitis C was not significant.

Abbreviations

- HBcAb

anti-HBc (IgG) antibody

- HBsAb

anti-HBs antibody

- HBsAg

hepatitis B surface antigen

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- LC

liver cirrhosis

References

- 1.Mason A, Yoffe B, Noonan C, Mearns M, Campbell C, Kelley A, et al. Hepatitis B virus DNA in peripheral-blood mononuclear cells in chronic hepatitis B after HBsAg clearance. Hepatology. 1992;16:36–41. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840160108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raimondo G, Pollicino T, Cacciola I, Squadrito G. Occult hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2007;46:160–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noborg U, Gusdal A, Horal P, Lindh M. Levels of viraemia in subjects with serological markers of past or chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Scand J Infect Dis. 2000;32:249–252. doi: 10.1080/00365540050165866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paterlini P, Poussin K, Kew M, Franco D, Brechot C. Selective accumulation of the X transcript of hepatitis B virus in patients negative for hepatitis B surface antigen with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 1995;21:313–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cacciola I, Pollicino T, Squadrito G, Cerenzia G, Villari D, de Franchis R, et al. Quantification of intrahepatic hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA in patients with chronic HBV infection. Hepatology. 2000;31:507–512. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allain JP. Occult hepatitis B virus infection: implications in transfusion. Vox Sang. 2004;86:83–91. doi: 10.1111/j.0042-9007.2004.00406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bréchot C, Thiers V, Kremsdorf D, Nalpas B, Pol S, Paterlini-Bréchot P. Persistent hepatitis B virus infection in subjects without hepatitis B surface antigen: clinically significant or purely "occult"? Hepatology. 2001;34:194–203. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.25172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu KQ. Occult hepatitis B virus infection and its clinical implications. J Viral Hepat. 2002;9:243–257. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2002.00344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Torbenson M, Thomas DL. Occult hepatitis B. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:479–486. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(02)00345-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sagnelli E, Imparato M, Coppola N, Pisapia R, Sagnelli C, Messina V, et al. Diagnosis and clinical impact of occult hepatitis B infection in patients with biopsy proven chronic hepatitis C: a multicenter study. J Med Virol. 2008;80:1547–1553. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yotsuyanagi H, Yasuda K, Iino S, Moriya K, Shintani Y, Fujie H, et al. Persistent viremia after recovery from self-limited acute hepatitis B. Hepatology. 1998;27:1377–1382. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bläckberg J, Kidd-Ljunggren K. Occult hepatitis B virus after acute self-limited infection persisting for 30 years without sequence variation. J Hepatol. 2000;33:992–997. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80134-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rehermann B, Ferrari C, Pasquinelli C, Chisari FV. The hepatitis B virus persists for decades after patients' recovery from acute viral hepatitis despite active maintenance of a cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response. Nat Med. 1996;2:1104–1108. doi: 10.1038/nm1096-1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liaw YF, Sheen IS, Chen TJ, Chu CM, Pao CC. Incidence, determinants and significance of delayed clearance of serum HBsAg in chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a prospective study. Hepatology. 1991;13:627–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loriot MA, Marcellin P, Walker F, Boyer N, Degott C, Randrianatoavina I, et al. Persistence of hepatitis B virus DNA in serum and liver from patients with chronic hepatitis B after loss of HBsAg. J Hepatol. 1997;27:251–258. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(97)80168-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scheuer PJ. Classification of chronic viral hepatitis: a need for reassessment. J Hepatol. 1991;13:372–374. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(91)90084-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conjeevaram HS, Lok AS. Occult hepatitis B virus infection: a hidden menace? Hepatology. 2001;34:204–206. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.25225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song EY, Yun YM, Park MH, Seo DH. Prevalence of occult hepatitis B virus infection in a general adult population in Korea. Intervirology. 2009;52:57–62. doi: 10.1159/000214633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang SY, Kim MH, Lee WI. The prevalence of "anti-HBc alone" and HBV DNA detection among anti-HBc alone in Korea. J Med Virol. 2010;82:1508–1514. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chemin I, Zoulim F, Merle P, Arkhis A, Chevallier M, Kay A, et al. High incidence of hepatitis B infections among chronic hepatitis cases of unknown aetiology. J Hepatol. 2001;34:447–454. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)00100-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cacciola I, Pollicino T, Squadrito G, Cerenzia G, Orlando ME, Raimondo G. Occult hepatitis B virus infection in patients with chronic hepatitis C liver disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:22–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907013410104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sagnelli E, Coppola N, Scolastico C, Mogavero AR, Filippini P, Piccinino F. HCV genotype and "silent" HBV coinfection: two main risk factors for a more severe liver disease. J Med Virol. 2001;64:350–355. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mariscal LF, Rodríguez-Iñigo E, Bartolomé J, Castillo I, Ortiz-Movilla N, Navacerrada C, et al. Hepatitis B infection of the liver in chronic hepatitis C without detectable hepatitis B virus DNA in serum. J Med Virol. 2004;73:177–186. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fukuda R, Ishimura N, Niigaki M, Hamamoto S, Satoh S, Tanaka S, et al. Serologically silent hepatitis B virus coinfection in patients with hepatitis C virus-associated chronic liver disease: clinical and virological significance. J Med Virol. 1999;58:201–207. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199907)58:3<201::aid-jmv3>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koike K, Kobayashi M, Gondo M, Hayashi I, Osuga T, Takada S. Hepatitis B virus DNA is frequently found in liver biopsy samples from hepatitis C virus-infected chronic hepatitis patients. J Med Virol. 1998;54:249–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uchida T, Kaneita Y, Gotoh K, Kanagawa H, Kouyama H, Kawanishi T, et al. Hepatitis C virus is frequently coinfected with serum marker-negative hepatitis B virus: probable replication promotion of the former by the latter as demonstrated by in vitro cotransfection. J Med Virol. 1997;52:399–405. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199708)52:4<399::aid-jmv10>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koike K, Nakamura Y, Kobayashi M, Takada S, Urashima T, Saigo K, et al. Hepatitis B virus DNA integration frequently observed in the hepatocellular carcinoma DNA of hepatitis C virus-infected patients. Int J Oncol. 1996;8:781–784. doi: 10.3892/ijo.8.4.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim JH, Kim YS, Suh DJ. The prevalence of HBsAg and anti - HCV in Korean patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Korean J Med. 1994;46:181–190. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kazemi-Shirazi L, Petermann D, Müller C. Hepatitis B virus DNA in sera and liver tissue of HBsAg negative patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2000;33:785–790. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80311-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mariscal LF, Rodríguez-Iñigo E, Bartolomé J, Castillo I, Ortiz-Movilla N, Navacerrada C, et al. Hepatitis B infection of the liver in chronic hepatitis C without detectable hepatitis B virus DNA in serum. J Med Virol. 2004;73:177–186. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prieto M, Gómez MD, Berenguer M, Córdoba J, Rayón JM, Pastor M, et al. De novo hepatitis B after liver transplantation from hepatitis B core antibody-positive donors in an area with high prevalence of anti-HBc positivity in the donor population. Liver Transpl. 2001;7:51–58. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2001.20786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lok AS. Occult hepatitis B virus infection: diagnosis, implications and management? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19(Suppl):S114–S117. [Google Scholar]