Abstract

Facial nerve palsy due to temporal bone metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) has rarely been reported. We experienced a rare case of temporal bone metastasis of HCC that initially presented as facial nerve palsy and was diagnosed by surgical biopsy. This patient also discovered for the first time that he had chronic hepatitis B and C infections due to this facial nerve palsy. Radiation therapy greatly relieved the facial pain and facial nerve palsy. This report suggests that hepatologists should consider metastatic HCC as a rare but possible cause of new-onset cranial neuropathy in patients with chronic viral hepatitis.

Keywords: Metastasis, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Temporal bone, Cranial nerve palsy

INTRODUCTION

Temporal bone metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) has rarely been reported.1 Only one case of facial nerve palsy due to temporal bone metastasis of HCC has been reported and it was detected by autopsy.2 We encountered a case of metastatic HCC to the temporal region of the skull that initially presented as facial nerve palsy and was incidentally found during the diagnostic work up.

CASE REPORT

A 61-year-old man visited our hospital because of progressively worsening right facial pain and numbness over a 6-month period. The pain had developed insidiously and had been occurring intermittently. He could not make abrupt facial expressions on the right side of his face for seven days before he came to our hospital. He had a squeezing headache on the right side of his head. He had no history of previous illness.

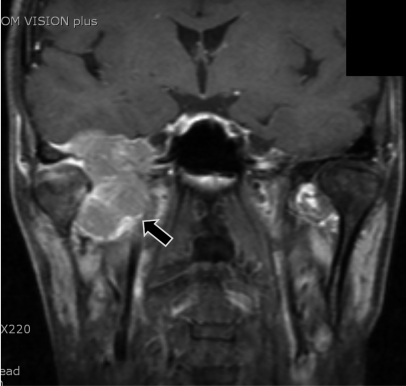

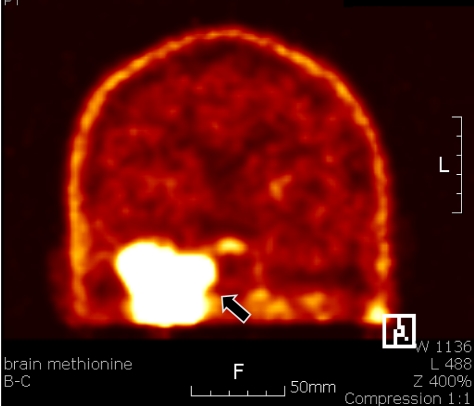

On physical examination, he had paresthesia and hypesthesia over all territories of 3 branches of the trigeminal nerve, facial palsy in the right side of his face, and hearing loss without tinnitus in his right ear. Other cranial nerve examinations were normal. In nasopharyngeal magnetic resonance image (MRI), a 5-cm, heterogeneously enhancing tumor was found in T1 weighted image (Fig. 1). The tumor was located in the masticator space and right middle cranial fossa, abutting the right cavernous sinus and extending intracranially to the right ipsilateral infratemporal fossa. The tumor was hypermetabolic in positron emission tomography (PET) study using C-11-methionine, which suggested that the tumor might be a malignant lesion (Fig. 2). Bony destruction of the anterior wall, which was adjacent to the anterior genu portion of the facial nerve, was suspected to be the cause of facial nerve palsy.

Figure 1.

T1-weighted MRI of the nasopharyngeal region revealed a 5-cm heterogeneously enhanced mass (arrow) located mainly in the right masticator space and middle cranial fossa, abutting the right cavernous sinus and with an intracranial extension to the right ipsilateral infratemporal fossa.

Figure 2.

C-11-methionine PET revealed a hypermetabolic lesion (arrow) at the right temporal lobe of the brain, suggesting a malignant tumor.

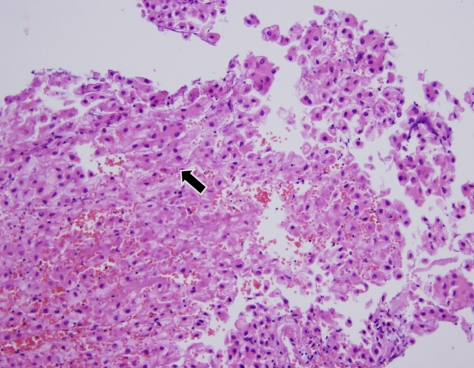

The patient was admitted for surgical biopsy of the tumor. His laboratory findings were as follows: white blood cell count was 6,900 per mm3, hemoglobin was 15.3 g/dL, platelet was 152,000 per mm3, serum albumin was 3.4 g/dL, total bilirubin was 1.1 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase was 134 IU/L, aspartate aminotransferase was 97 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase was 192 IU/L, gamma glutamyltransferase was 131 IU/L, and prothrombin time evealed 1.1 international normalized ratio. The serologic finding revealed positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), antibody to hepatitis B envelop antigen (HBeAg) and antibody to hepatitis C virus (anti-HCV). His serum hepatitis B virus DNA level was 97,200 IU/mL. Serum alpha-fetoprotein was 5,200 ng/mL and des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin was 17,268 nAU/mL. Endoscopic surgical biopsy with sphenoidotomy via the right nasal cavity was performed by an otolaryngologist. During surgical biopsy, a bulging tumor was found adjacent to the inferolateral wall through the destroyed bone. The pathological finding was consistent with metastatic HCC (Fig. 3). Immunohistochemical findings of the biopsy specimen revealed positive staining for alpha-fetoprotein, which was also consistent with metastatic HCC (Fig. 4). Other metastases were found in lumbar spines (L1, L2) and right femur in bone scan. Radiation therapy was performed for the tumor in the masticator space and right middle cranial fossa and for the metastatic lesions in lumbar spines and right femur. After radiation therapy was finished, his facial pain subsided significantly and his facial nerve palsy was partially relieved. Facial pain did not occur again and facial nerve palsy did not progress until 7 months later.

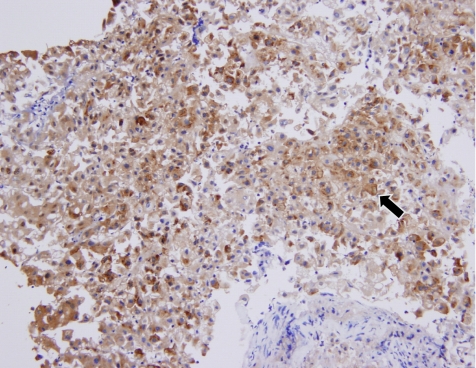

Figure 3.

Photomicrograph of the biopsy specimen showing cords of large neoplastic cells with oval nuclei resembling hepatocytes (arrow), which suggests metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma (H&E stain, ×200).

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry of the biopsy specimen with anti-alpha-fetoprotein antibody revealed a diffusely stained pattern over cords of large neoplastic cells with oval nuclei resembling hepatocytes (arrow), which is consistent with a metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma (alpha-fetoprotein, ×200).

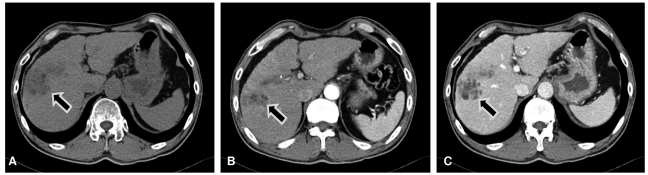

To evaluate the primary HCC in liver, abdominal computed tomography (CT) was performed. A 5-cm-sized, fat-containing, ill-defined and subtly enhanced mass lesion was found in segment 8 in the cirrhotic liver (Fig. 5). Although repeated transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) was tried 3 times over 7 months to treat this tumor, only marginal lipiodol uptake was observed with each TACE.

Figure 5.

Abdominal CT revealed a 5-cm fat-containing, ill-defined, and subtly enhanced mass lesion in segment 8 (arrow) in the cirrhotic liver. (A) precontrast, (B) arterial phase, (C) portal phase.

Seven months after initial diagnosis of metastatic HCC, back pain occurred over 2 weeks. Bone scan and spinal MRI showed progressed spinal metastasis. As no therapy remained for the multiple spinal metastases, the patient was transferred to a hospital near his home for supportive care.

DISCUSSION

Temporal bone metastasis of HCC has rarely been reported.2 Though HCC commonly metastasizes to bone, metastasis of HCC to skull is uncommon.3 Facial palsy due to HCC was reported once in an advanced cirrhotic patient after autopsy.2 Therefore, our report might be the first case report of metastatic HCC to the temporal region of skull involving the facial and trigeminal nerve, as confirmed by surgical biopsy.2 Metastatic HCC was diagnosed by surgical biopsy in this case. Even if HCC had been found in liver prior to performing the biopsy of temporal metastatic lesion, tissue confirmation of the lesion in temporal area would have been done for proper management because exact diagnosis was needed for proper management and because the lesion could have been an isolated double primary tumor such as schwannoma.

As far as temporal bone metastasis of malignant tumors, bilateral temporal bone involvements are more common than unilateral involvement, but in this patient and the previous autopsy-proven case of temporal bone metastasis of HCC, the lesions were only on the right side.2 Hearing loss without vestibular manifestation was reported as the most common symptom of temporal bone metastases in a retrospective study of 47 autopsy cases, which was consistent with this case.4 In the case of facial palsy secondary to metastasis, involvement of other cranial nerves was more common than involvement of the facial nerve alone, which was also consistent with this case.4 Radiological investigation is strongly recommended if the facial nerve palsy is clinically associated with other neurological signs.5,6

Bone and brain metastases of HCC have been treated with palliative radiation therapy and pain relief has been observed in about 78% of patients, suggesting good responsiveness to radiation.7 Therefore, we performed radiation therapy for the metastatic lesion in the temporal area and the pain completely subsided. Our case may suggest that temporal bone metastasis of HCC is also a very good indication for radiation therapy.

Hepatic dysfunction is known to be the main prognostic factor in patients with HCC, even in patients with extrahepatic metastasis. The major survival factor for our patient might also be the progression of hepatic dysfunction.8,9 Sorafenib treatment might have been considered in this patient because the intrahepatic HCC progressed despite repeated TACE; however, sorafenib was not available during our caring for him.10,11

In summary, we encountered a very rare case of histologically proven temporal bone metastasis of HCC that was found during the evaluation of a patient who presented with trigeminal, facial and auditory nerve dysfunction and who was positive for both HBsAg and anti-HCV but without previous history of illness. Our case suggests that hepatologists may consider metastatic HCC as a rare cause of new onset cranial nerve palsy in patients with chronic viral hepatitis, and radiation therapy may be considered for the treatment of temporal bone metastasis of HCC with cranial nerve involvement.

Abbreviations

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- MRI

magnetic resonance image

- PET

positron emission tomography

- HBsAg

hepatitis B surface antigen

- HBeAg

hepatitis B envelop antigen

- anti-HCV

antibody to hepatitis C virus

- TACE

transarterial chemoembolization

References

- 1.Gloria-Cruz TI, Schachern PA, Paparella MM, Adams GL, Fulton SE. Metastases to temporal bones from primary nonsystemic malignant neoplasms. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;126:209–214. doi: 10.1001/archotol.126.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagai M, Yamada H, Kitamoto M, Ikeda J, Mori Y, Monzen Y, et al. Facial nerve palsy due to temporal bone metastasis from hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:1131–1132. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goto T, Dohmen T, Miura K, Ohshima S, Yoneyama K, Shibuya T, et al. Skull metastasis from hepatocellular carcinoma with chronic hepatitis B. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010;2:165–168. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v2.i3.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiss MD, Kattah JC, Jones R, Manz HJ. Isolated facial nerve palsy from metastasis to the temporal bone: report of two cases and a review of the literature. Am J Clin Oncol. 1997;20:19–23. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199702000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peitersen E. Bell's palsy: the spontaneous course of 2,500 peripheral facial nerve palsies of different etiologies. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 2002;549:4–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alaani A, Hogg R, Saravanappa N, Irving RM. An analysis of diagnostic delay in unilateral facial paralysis. J Laryngol Otol. 2005;119:184–188. doi: 10.1258/0022215053561477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hawkins MA, Dawson LA. Radiation therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: from palliation to cure. Cancer. 2006;106:1653–1663. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim SU, Kim DY, Park JY, Ahn SH, Nah HJ, Chon CY, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma presenting with bone metastasis: clinical characteristics and prognostic factors. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2008;134:1377–1384. doi: 10.1007/s00432-008-0410-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stuart KE, Anand AJ, Jenkins RL. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Prognostic features, treatment outcome, and survival. Cancer. 1996;77:2217–2222. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960601)77:11<2217::AID-CNCR6>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378–390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song IH. Molecular targeting for treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Korean J Hepatol. 2009;15:299–308. doi: 10.3350/kjhep.2009.15.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]