Abstract

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is associated with significant psychological distress, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). However, factors that attenuate the impact of IPV on PTSD remain largely unknown. Using hierarchical regression, this investigation explored the impact of resource acquisition and empowerment on the relationship between IPV and PTSD. Empowerment demonstrated greater relative importance over resource acquisition. Specifically, empowerment was found to attenuate the impact of IPV severity on PTSD at low and moderate levels of violence. The importance of fostering empowerment and addressing PTSD in addition to provision of resources in battered women is discussed.

Keywords: intimate partner violence, PTSD, empowerment

INTRODUCTION

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a public health crisis that takes an enormous toll on women worldwide both physically and psychologically. Nearly 25% of American women are directly affected by some form of violence perpetrated by an intimate partner (Tjaden & Thoennes, 2000). Of those, more than 40% of abused women reported being injured during their most recent assault (Tjaden & Thoennes, 2000). In addition to these physical consequences of abuse, many victims also experience trauma sequelae including posttraumatic stress, depression, suicide attempts, and other psychiatric and unspecified concerns. (Bergman & Brismar, 1991; Hathaway, Mucci, Silverman, Brooks, Mathews, & Pavlos 2000; Sutherland, Bybee, & Sullivan, 2002).

The mental health consequence most frequently associated with IPV is posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Golding, 1999) with research estimating that an average of 64% of battered women meet DSM-IV diagnostic criteria (Jones, Hughes, & Unterstaller, 2001). PTSD consists of re-experiencing, avoidance, emotional numbing, and hyper-arousal symptoms secondary to a traumatic event (APA, 2000). The relationship between the severity of IPV and PTSD symptomatology has been well established (Bargai, Ben-Shakhar, & Shalev, 2007; Bennice, Resick, Mechanic, & Astin, 2003; Campbell, 2002; Cascardi, O’Leary, & Schlee, 1999; Jones et al., 2001; Kemp, Green, Hovanitz, & Rawlings, 1995; Stein & Kennedy, 2001; Taft, Vogt, Mechanic, & Resick, 2007). Further, battered women residing in domestic violence shelters often experience greater severity of violence and injury compared to abused women not in shelters (Gondolf, 1998). Due to experiencing higher levels of violence, battered women in shelters also are more likely to exhibit higher rates and severity of IPV- related PTSD (Jones et al., 2001; Kemp, Rawlings, & Green, 1991; Saunders, 1994). However, little is known regarding the factors that may attenuate the impact of IPV on PTSD for battered women residing in shelters. To address this gap in clinical practice, the current study focuses on two potential attenuating factors emphasized in the literature, resource acquisition and personal empowerment.

IPV, PTSD, and Domestic Violence Shelters

Prior research with battered women (Johnson, Zlotnick, & Perez, 2008; Krause, Kalmtan, Goodman, & Dutton, 2008; Perez & Johnson, 2008) suggests that symptoms of IPV-related PTSD interfere with women’s effective use of resources and with their ability to establish long-term safety for themselves and their children. As IPV often results in the loss of many tangible resources including safe housing, financial security, and other basic necessities, domestic violence shelters often focus on resource acquisition for their residents (Roberts & Burman, 2007; Sullivan & Gillum, 2001). This provision of tangible resources often includes emergency housing and case management services to help access other resources including public housing programs, educational opportunities, and job retraining programs (Macy, Giattina, Sangster, Crosby, & Montijo, 2009; Roberts & Burman, 2007; Sullivan & Gillum, 2001). Shelters provide women with the opportunity to begin working towards reestablishing their independence in a safe environment, free from abuse with the ultimate goal of helping women gain independence and cease the violence in their lives.

In order to effectively use the tangible resources provided by domestic violence shelters, women must achieve a high level of functioning (Johnson et al., 2008). For women suffering from symptoms of PTSD, however, navigating a multitude of social services agencies while combating PTSD symptoms can be a daunting task. Moreover, PTSD symptoms may even inhibit women from being able to fully utilize resources provided by battered women’s shelters. Loss of resources has been linked to an increase in mental health symptoms, and with PTSD symptoms in particular (Hobfoll, 1989). To the extent that women have difficulties securing resources for themselves and their children, PTSD symptoms may worsen. Therefore, the provision of resources in isolation may be insufficient for assisting battered women with IPV-related PTSD and associated impairment in functioning.

In addition to the provision of resources, a philosophical goal underlying the interventions used by many domestic violence shelters is fostering a sense of personal empowerment (Kasturirangan, 2008). Although resource acquisition and empowerment are theoretically overlapping constructs, models of empowerment tend to rely on feminist theory and emphasize a woman’s ability to effectively use available resources rather than focus solely on the acquisition of resources. Therefore, the concept of empowerment and how to best “foster” empowerment has long been of interest to mental health practitioners. Despite this interest, empowerment research has been stifled by a lack of agreement on the best way to conceptualize and empirically study this concept. Empowerment has been broadly defined as “the process of gaining influence over events and outcomes of importance to an individual or group” (Foster-Fishman, Salem, Chibnall, Legler, & Yapchai, 1998, p. 508). It is theorized to be a dynamic concept, meaning different things to different groups of people and that what is thought to be “empowering” may change based on time and circumstance (Foster-Fishman et al., 1998; Zimmerman, 2000).

As with research on empowerment, programs and service agencies working to empower battered women often suffer from the same difficulties in that poor understanding of the concept negatively impacts achieving the goal of empowerment. Kasturirangan (2008) suggests that programs and agencies wishing to identify empowerment as a goal must work towards developing an “empowerment process” with their clients as a means of gaining a sense of control or mastery. This process will likely entail women setting their own goals and enabling access to resources that will assist clients in achieving these individualized goals (Kasturirangan, 2008) in order for empowerment to serve as a protective factor against PTSD.

For the current investigation, the operational definition as put forth by Johnson, Worell, and Chandler (2005) is employed, defining empowerment as “enabling women to access skills and resources to cope more effectively with current as well as future stress and trauma” (p. 109). Based on this broad definition, empowerment is further conceptualized as encompassing a set of attitudes and behaviors including positive self-evaluation and self-esteem, a favorable comfort/distress ratio, gender-role and cultural identity awareness, a sense of personal control/self-efficacy, self-nurturance and self-care, effective problem-solving skills, competent use of assertiveness skills, effective access to multiple economic, social, and community resources, gender and cultural flexibility, and socially constructive activism (Worrell & Remer, 2003).

It is our belief that a theoretically grounded feminist framework provides a basis on which to begin to empirically study empowerment. Specifically, a feminist framework highlights the interrelationship between personal and cultural identities for women, and how they are grounded within a broader sociopolitical context. Further, this strengths-based model emphasizes the value of emotional expression and nurturing supportive relationships with other women. Based on the definitions offered above, the self-report measure, Personal Progress Scale-Revised, was constructed and validated (Johnson, et al., 2005). Previous research using this scale has shown empowerment to be a protective personal resource against the impact of IPV supporting the theoretical notion that empowerment provides protection against trauma sequelae (Johnson et al., 2005). This conceptualization of empowerment serves as a starting point for our understanding of empowerment and is consistent with the empowerment goals of many feminist based programs, including battered women’s shelters (Kasturirangan, 2008; Macy et al., 2009).

IPV Severity, Resource Acquisition, and Empowerment

The current investigation seeks to further our understanding of factors that may attenuate the impact of IPV-related PTSD symptoms in women residing in domestic violence shelters. Because PTSD has been shown to have a detrimental impact on battered women’s psychosocial functioning and future safety, a more complete understanding of potential attenuating factors are needed for helping professionals to assist battered women in achieving long term safety. Using a population of women residing in domestic violence shelters, we examined the roles of resource acquisition (i.e., part of the “standard care” that women receive upon entering a shelter”) and empowerment (i.e., the philosophical goal underlying many programs that assist battered women) on PTSD symptoms (Kasturirangan, 2008; Macy et al., 2009) with the ultimate goal of furthering our understanding of factors that impact PTSD to determine if more specialized interventions may be warranted.

Further, due to the severity of violence experienced by battered women in shelter, it is possible that factors that attenuate the impact of PTSD symptoms may be more or less protective given the level of violence severity experienced. For example, previous research investigating the protective impact of social support in battered women found that this resource was protective against future abuse except for those who experienced the highest levels of violence severity, where social support ceased to relate to risk for future abuse (Goodman, Dutton, Vankos, & Weinfurt, 2005). Therefore, in the current investigation we explored the potential moderating role of resource acquisition and empowerment in the relationship between IPV severity and IPV-related PTSD symptoms.

METHOD

Data were collected from 227 residents of a battered women shelter. Participants were recruited from two shelters within the same shelter system over approximately four years located in an urban medium mid-western city. These shelters both provide “emergency protective shelter and a supportive environment for women and their children fleeing an abusive situation,” work to prevent domestic violence, and educate and empower survivors of domestic violence. Services offered by the shelter system include emergency housing and access to basic resources, case management, support group, and advocacy programs. One shelter in the system provides emergency crisis stabilization while the other provides apartment-style transitional living space. Generally, women were admitted to the crisis stabilization shelter and then a sub-set continue on to the transitional living facility although some larger families were directly admitted to the apartment style living facility (SCMCBWS, 2009). During the four years of data collection, the mission of the shelter system, as well as the key executive personnel guiding the shelter mission remained unchanged.

Women were invited to complete an interview for the current study if they were residents of the battered women’s shelter and had a documented incident of abuse from an intimate partner as defined by their responses to the Conflict Tactics Scale 2 (CTS-2) (see below). Study procedures were approved by the relevant Institutional Review Board and all participants signed a written informed consent explaining the purpose of the research, risks and benefits of participating in the study, that they have the right to withdraw at any time, and participation would not impact their stay in shelter. Participants were interviewed by trained graduate students in psychology or counseling under the direct supervision of a licensed psychologist. Measures employed in the present study are described below.

Measures

IPV-severity

The Revised Conflict Tactic Scales (CTS-2) (Straus, Hamby, McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996) were used to assess the severity of abuse participants experienced the month before entering the domestic violence shelter. The CTS-2 is a self-report measure on which participants rate the frequency that each abusive act occurred on a 6-point rating scale. Thirty-three items assessing psychological aggression, physical assault, sexual coercion, and abusive acts resulting in injury were summed to create an index of the overall severity of abuse in the month preceding shelter admission. Examples of scale items include, “My partner insulted or swore at me,” (psychological aggression), “My partner threw something at me that could hurt,” (physical assault), “I had a sprain, bruise, or small cut because of a fight with my partner,” (injury) and “My partner used force (like hitting, holding down, or using a weapon) to make me have oral or anal sex.” (sexual coercion). The CTS-2 has established reliability with alphas ranging from .79-.95 (Straus, et al., 1996). Further, the CTS-2 has demonstrated discriminant validity as both the sexual coercion and injury scale have non-significant correlations with the negotiation scale, a theoretically unrelated construct (r’s<.05) (Straus et al., 1996). Excellent reliability also was demonstrated with the current sample (α = .94).

PTSD severity

The Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) (Blake, Weathers, Nagy, Kaloupek, Gusman, Charney, & Keane, 1995) is a semi-structured clinical interview that assesses the diagnostic criteria and severity of PTSD. The frequency and severity of participants’ re-experiencing, avoidance, and arousal symptoms were rated on a 5-point scale. Current PTSD was assessed for the complete IPV women experienced from the partner that led to their shelter admission, rather than having clients select one abusive incident and attempt to rate frequency and intensity of symptoms related to only that one event. Inter-rater reliability was assessed for 21 randomly selected interviews for CAPS-derived PTSD diagnoses (kappa = .83). The present study employs CAPS 1-week summed frequency and intensity of symptom status scores that correspond to the 17 criteria required for PTSD diagnosis. For example, to assess intrusive thoughts, participants were asked, “In the last week, have you had unwanted memories of the abuse?” Participants were then asked how often the intrusions occurred (once in the past week, twice in the past week, several times in the past week, or almost every day). Severity of the intrusions was then rated on a 5-point scale from absent to extreme. PTSD severity was calculated by summing the frequency and intensity scores of the re-experiencing, avoidance, and hyperarousal criteria. The measure has demonstrated internal reliability (α’s between .73-.85) and concurrent validity with other empirically validated measures of PTSD including the Mississippi Scale for Combat Related PTSD, the PTSD subscale of MMPI, and the Combat Exposure Scale (r’s between .42-.84) (Blake et al., 1995). The measure demonstrated strong reliability within the current sample (α = .93).

Resource acquisition

The Conservation of Resources – Evaluation (COR-E) (Hobfoll & Lilly, 1993) is a 74 item self-report measure that assesses the degree to which participants experienced gain in material, energy, work, interpersonal, family, and personal (i.e., mastery and self-esteem) resources in the past month. Each item of the COR-E is rated on a three-point scale ranging from zero (no gain), one (some gain), or two (a great deal of gain) and then summed for a total score. The COR-E has demonstrated excellent concurrent, divergent, and predictive validity in community-based and trauma-based samples (Hobfoll & Lilly, 1993; Ironson, Wynings, Schneiderman, Baum, Rodriguez, Greenwood et al., 1997) with α’s between .85-.86 (Hobfoll, Johnson, Ennis, & Jackson, 2003), and had excellent reliability within the current sample (α = .97).

Empowerment

The Personal Progress Scale-Revised (PPS-R) (Johnson et al., 2005) was used to measure women’s empowerment. The PPS-R is a previously validated, 28 item self-report measure on which participants rated the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with each item on a 7-point Likert scale and then summed to create a total score. The PPS-R is based on the four principles of the Empowerment model: Personal and Social Identities are Interdependent, Personal is Political, Relationships are Egalitarian, and Women’s Perspectives are Valued (Worrell & Remer, 2003). The PPS-R assesses 10 broad outcomes of feminist therapies including positive self-evaluation and self-esteem, a favorable comfort distress ratio, gender-role and cultural identity awareness, a sense of personal control/self-efficacy, self-nurturance and self-care, effective problem-solving skills, competent use of assertiveness skills, effective access to multiple economic, social, and community resources, gender and cultural flexibility, and socially constructive activism (Worrell & Remer, 2003). Example items include, “I have equal relationships with important others in my life,” “It is difficult for me to be assertive with others when I need to be” (reverse scored), “I am feeling in control of my life,” and “I feel comfortable in confronting my supervisors at school or work when we see things differently.<s>1” Previous research with the PPS-R has shown the measure to have good reliability and validity (Johnson et al., 2005). Further, the measure has shown excellent discriminant validity as it was able to distinguish between victims of IPV with and without PTSD in previous research (Johnson et al., 2005). Alpha in the current instance was .84.

Trauma History

The Trauma History Questionnaire (THQ) (Green, 1996) is a 24 item self-report questionnaire utilized to gather information on participants’ experiences of potentially traumatic events over the course of their lifetime. The participants are asked if they ever experienced several different types of traumatic events including, “Has anyone ever tried to take something directly from you by using force, threat of force, such as a stick up or mugging?” and “Has anyone, including family members or friends, ever attacked you with a gun, knife, or some other weapon?” Total number of types of trauma reported on the THQ were summed to create an index score. Participants are instructed to not include incidents that only occurred with their most recent abusive partner as to not duplicate information included on the CTS-2 (see above). Previous research has shown acceptable test-retest reliability (Green, 1996). The number of types of potentially traumatic events endorsed are included as a covariate in multivariate analyses.

Analyses

Regression analyses

To determine the attenuating impact of resource acquisition and empowerment on PTSD symptoms in the context of IPV severity, a hierarchical regression analysis was conducted. Further, to explore if there were any differences in the attenuating impact of these factors at different levels of IPV severity, interaction terms also were created between both protective factors (i.e., resource acquisition and empowerment) and intimate partner violence severity. Each term was mean centered and then multiplied together to create two interaction terms: IPV Severity X Resource Acquisition and IPV Severity X Empowerment. All analyses controlled for demographic variables that were significantly correlated with PTSD in correlation analyses, including minority status which was dummy coded (0=non-minority, 1=minority), (r(226)=−.17, p=.01), trauma categories (r(226)=−.21, p<.01), and length of shelter stay prior to completing the interview (r(226)=−.17, p<.05). No other significant relationships were found between PTSD severity and demographic variables.

In the first step, minority status, number of types of prior traumas, and length of shelter stay prior to completing the interview were included as covariates. The mean centered terms of severity of violence, resource acquisition, and empowerment were entered individually in successive steps. Resource acquisition was entered prior to empowerment as resource acquisition represents the “standard care” that the majority of shelters are currently providing to their clients (Macy, et al., 2009; Sullivan & Gillum, 2001). Empowerment was entered in the following step as we were interested in any additional protection empowerment may provide against PTSD. In the final step, the interaction terms between IPV severity and resource acquisition and IPV severity and empowerment were entered. Terms were considered significant if the F value for the change in R2 associated with each step was significant at p≤.05.

RESULTS

Less than 1% of the total data was missing and no participant had significant missing data on any single measure, so all participants were included in the study. Approximately 45.8% of participants self-identified as African-American, 37.0% as Caucasian, 8.4% Hispanic and 8.8% another race. Most participants were married to or cohabiting with their abuser (84.2%) prior to entering the shelter. Ninety-two percent of participants identified as heterosexual, with remaining participants identifying as lesbian or bisexual. Most had at least a high-school degree or equivalent (75.3%), were currently unemployed (74.0%), and were receiving public assistance (59.5%). Participants ranged in age from 18 to 64 (M = 34.56, SD = 9.03) and reported experiencing between 0 and 20 different types of traumatic events during their lifetime (M=7.19, SD=4.35). Length of shelter stay prior to interview ranged between 1 and 127 days (M=17.26, SD=15.19). On average, women were in shelter 17 days (M=17.26, SD=15.19), attended just over 3 (M=3.16, SD=4.59) case management meetings, nearly 2 (M=1.76, SD=1.98) support group meetings, and approximately 1 parenting group (M=.79, SD=1.59) prior to completing the interview. Descriptive statistics and correlations among all study variables are found in Table 1. Of the 227 participants included in the present study, 152 (67%) met criteria for IPV-related PTSD as assessed by the CAPS interview. Mean length of PTSD symptoms was approximately three years.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics and Pearson’s Correlations Among Independent and Dependent Variables (N = 227).

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAPS | 53.02 | 27.46 | -- | ||||||

| Minority Status |

-- | -- | −.17** | -- | |||||

| # of types of trauma |

7.19 | 4.35 | .21** | −.04 | -- | ||||

| Length of Shelter stay |

17.26 | 15.19 | −.17* | .09 | −.12 | -- | |||

| CTS-2 | 46.87 | 32.90 | .22*** | .04 | .01 | −.07 | -- | ||

| COR-E Gain |

46.62 | 26.14 | −.22*** | .21** | −.12 | .23*** | −.08 | -- | |

| PPS-R | 126.08 | 22.33 | −.35*** | .30*** | −.13 | .24*** | −.13 | .44*** | -- |

Note.

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001.

CAPS: Clinician Administered PTSD Scale, CTS-2: Conflict Tactics Scale-Revised, COR-E Gain: Conservation of Resource Evaluation-Gains, PPS-R: Personal Progress Scale-Revised.

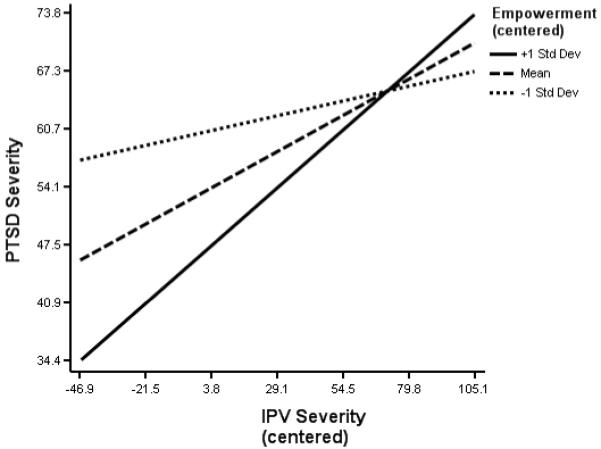

Resource Acquisition, Empowerment and Violence on PTSD Severity

Results of regression analyses investigating the impact of resource acquisition and empowerment on the relationship between IPV severity and PTSD severity can be found in Table 2. In the first step, of the covariates entered, both minority status, number of types of previous traumas, and length of shelter stay prior to interview were significantly related to PTSD severity (F(3,223)=6.96, p<.001). In the following steps, both violence severity and resource acquisition were found to have significant relationships with PTSD (F(1,222)=8.42, p<.001, F(1,221)=7.65, p<.001). However, when empowerment is entered in the following step, empowerment obtains a significant relationship with PTSD; IPV severity remains significant while resource acquisition loses significance (F(1,220)=8.74, p<.001). In the final step, the interaction between IPV severity and empowerment, but not IPV severity and resource acquisition, achieves significance suggesting that empowerment attenuates the impact of IPV severity on PTSD at low and moderate levels of violence (F(2,218)=7.45, p<.001). See Figure 1 for a graphical representation of the interaction between IPV severity and empowerment on PTSD severity.

Table 2.

Results of Hierarchical Linear Regression Analyses Investigating IPV Severity, Resource Acquisition, and Empowerment on PTSD severity (N=227)

| DV | Step | IV | R<s>2 | Adj. R<s>2 |

Δ R<s>2 |

Beta | F | FΔ | d.f. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTSD | 1 | Minority status | .09 | .07 | .09 | −.15* | 6.96*** | 6.96*** | 3,223 |

| Types of trauma | .19** | ||||||||

| Shelter stay | −.13* | ||||||||

| 2 | Minority status | .13 | .12 | .05 | −.16* | 8.42*** | 11.79*** | 1,222 | |

| Types of trauma | .19** | ||||||||

| Shelter Stay | −.12 | ||||||||

| IPV Severity | .22*** | ||||||||

| 3 | Minority status | .15 | .13 | .02 | −.14* | 7.65*** | 4.11* | 1,221 | |

| Types of trauma | .17** | ||||||||

| Shelter stay | −.09 | ||||||||

| IPV severity | .21*** | ||||||||

|

Resource

acquisition |

−.13* | ||||||||

| 4 | Minority status | .19 | .17 | .05 | −.08 | 8.74*** | 12.26*** | 1, 220 | |

| Types of trauma | .16** | ||||||||

| Shelter stay | .18** | ||||||||

| IPV Severity | .06 | ||||||||

| Resource acquisition |

−.05 | ||||||||

| Empowerment | −.25*** | ||||||||

| 5 | Minority status | .22 | .19 | .02 | −.09 | 7.45*** | 3.09* | 2,218 | |

| Types of trauma | .16* | ||||||||

| Shelter stay | −.05 | ||||||||

| IPV Severity | .21*** | ||||||||

| Resource acquisition |

−.07 | ||||||||

| Empowerment | −.23*** | ||||||||

|

Empowerment

X IPV Severity |

.18* | ||||||||

|

Resource

Acquisition X IPV Severity |

−.11 |

Note:

p ≤ .05

p ≤ .01

p ≤ .001.

Terms in italicized print represent variables added in that step.

Figure 1.

Interaction between intimate partner violence severity and empowerment on PTSD symptom severity controlling for minority status, number of traumas, and resource acquisition.

DISCUSSION

This research is the first to our knowledge to empirically investigate the protective impact of resource acquisition on the relationship between IPV severity and IPV-related PTSD. When examined in a hierarchical manner, results suggest that resource acquisition initially had a significant impact on the relationship between IPV severity and PTSD symptoms, but when the additional impact of empowerment is considered, the relationship between resource acquisition and PTSD is no longer significant. Further, there appears to be a significant attenuating impact of empowerment on IPV severity related to PTSD severity. The attenuating impact of empowerment on PTSD symptoms, however, appears to occur only at low to moderate levels of IPV severity. At the highest levels of IPV severity there appears to be little difference between those with higher or lower levels of empowerment in relation to severity of PTSD symptoms. Overall, our findings highlight the important roles of safety planning, provision of resources, fostering empowerment, and directly addressing IPV-related PTSD symptoms when intervening with battered women living in shelters.

Our finding that acquisition of resources positively impacts PTSD severity is consistent with the practice of many domestic violence shelters to focus on the provision of resources to shelter residents (Macy et., 2009; Roberts & Burman, 2007; Sullivan & Gillum, 2001) and further underscores the importance of resource acquisition for battered women. However, our findings also suggest that empowerment is protective against PTSD symptoms above and beyond resource acquisition. This finding highlights the importance of fostering a sense of empowerment when intervening with battered women and suggests that the provision of resources alone may be insufficient to protect sheltered battered women from the deleterious effects of IPV-related PTSD.

The utility of empowerment appears to be complicated, however, for women who experience higher levels of violence. These survivors of IPV are more likely to suffer the negative physical and psychological consequences as the result of their severe abuse (Campbell, 2002; Cascardi et al., 1999; Dutton, Kaltman, Goodman, Weinfurt, & Vankos, 2005). The current results suggest that they may be less able to benefit from factors that attenuate the negative impact of abuse at less severe levels of violence, perhaps needing more time to benefit from these factors than their less severely abused counterparts. Other studies have found similar findings. Goodman and colleagues (2005) found that social support, another protective factor for women who experience violence in relationships, was protective against future violence except for the women who reported experiencing the highest levels of violence.

One potential explanation for the lessened protective impact of empowerment for women who experience severe levels of violence is that higher levels of empowerment may actually put them at risk for further abuse. For example, if a woman uses assertiveness skills with her severely abusive partner, the partner may be more likely to become increasingly abusive in response to her attempts to assert her power. Further research is needed to better understand the moderating role of IPV severity on the attenuating effect of empowerment on IPV-related PTSD. Regardless, it appears that at the highest levels of violence, protective factors may lose their potency and be insufficient for survivors of severe IPV. Given this, for victims of IPV with the most severe violence and therefore highest risk for PTSD (Campbell, 2002; Cascardi et al., 1999; Dutton et al., 2005), resource acquisition and empowerment alone may prove insufficient strategies. Therefore, especially for women with severe violence histories and IPV-related PTSD, interventions that focus on violence cessation and long-term safety as well as ameliorating IPV-related PTSD symptoms, are likely more important initially than either resource acquisition or empowerment alone. Further research investigating the most efficacious interventions for women who experience the highest severity of violence is clearly needed.

The significance of the current findings is particularly important for those working with battered women to help establish long-term safety. As with any intervention with battered women, establishing physical safety by achieving a cessation of violence must supercede other goals (Dutton, 1992; Foa, Cascardi, Zoellner, & Feeny, 2000). However, once immediate physical safety is achieved, resource provision and acquisition alone may prove insufficient in helping women cope with the aftermath of IPV; finding ways to foster empowerment may prove to be a powerful intervention. Preliminary research suggests that psychotherapeutic interventions that specifically foster empowerment and target IPV-related PTSD symptoms through a combination of psychoeducation, coping skills training, cognitive restructuring, and case management can be efficacious in reducing the psychological burden of IPV (Johnson & Zlotnick, 2006; Johnson & Zlotnick, 2009). These interventions may foster empowerment through promotion of the behaviors and attitudes consistent with an empowerment philosophy. Having alternative psychotherapeutic interventions for women who have PTSD secondary to IPV is particularly important as although effective treatments exist for PTSD (i.e. Prolonged Exposure Therapy, Cognitive Processing Therapy), these treatments are contraindicated for trauma survivors with ongoing safety concerns as is the case for women residing in domestic violence shelters (Johnson & Zlotnick, 2006).

Due to the cross-sectional nature of the current data, it is unclear whether women’s perceived empowerment was a result of intervention they may have received through shelter services or a pre-existing characteristic. Regardless, our results suggest that domestic violence shelters may wish to supplement traditional shelter services with such psychotherapeutic interventions designed to either foster or build upon empowerment to maximize the benefits of shelter for battered women. The mechanism by which empowerment is promoted is a potential direction for future longitudinal research. Regardless of the directionality of the relationship between empowerment and PTSD, results do suggest that empowerment is an important factor relating to IPV survivors’ mental health.

Many programs offering services to women who have experienced violence in relationships list empowerment as a goal for program participants (Kasturirangan, 2008). The current investigation highlights the importance of this goal, although previous research suggests that programs should work towards making empowerment a concrete goal rather than an ill-defined ideal (Kasturirangan, 2008). The present investigation is one of a few attempts in the literature to operationalize and empirically study the concept of empowerment and to investigate the protective role of empowerment on IPV-related PTSD. Empowerment is a multi-determined and dynamic concept, with different groups and individuals identifying different experiences and societal structures as empowering. The conceptualization used in the current investigation represents a step towards making empowerment a more concrete goal of helping agencies through a firmer understanding of the concept. Moreover, the current investigation uses a theoretically derived and previously validated broad-based measure to assess the construct of empowerment. These results lend further support to the use of this measure as our results show empowerment is protective against post-trauma sequelae and is theoretically consistent with our understanding of empowerment (Johnson et al., 2005; Worrell & Remer, 2003), providing further construct validity for the PPS-R.

The cross-sectional design of the current research limits any conclusions that can be drawn about the direction of the relationships between IPV, PTSD, and attenuating factors such as resource acquisition and empowerment. For example, it may be that women who do not experience prolonged and severe post traumatic reactions from violence experience higher levels of empowerment. Longitudinal research is needed to determine the causality of these relationships. Additionally, findings may not generalize to battered women who do not seek shelter and mostly reflect women’s functioning within a shelter environment and may not accurately represent women’s functioning prior to or after shelter residence. Unfortunately, data was not available on those who declined to participate so no comparisons can be made between participants and non-participants.

Strengths of this research, however, include the use of a relatively large, ethnically diverse, and well-defined sample of battered women in shelters with standardized interviews administered by trained clinicians to assess IPV-related PTSD. Standardized information on empowerment, resource acquisition, and trauma history also was gathered. Furthermore, our findings are among the first to empirically study the concept of empowerment in a sample of battered women and examine its relationship to PTSD and underscore the importance of empowerment in relation to PTSD. These findings highlight the importance of investigating the directionality of the relationship between empowerment and PTSD and finding new and innovative ways to foster empowerment in battered women to protect against the psychosocial impairment often experienced as result of IPV-related PTSD symptoms.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIMH grant K23 MH067648 and pilot funds from the Summa-Kent State Center for the Treatment and Study of Traumatic Stress. We would like to thank Cynthia Cluster, Keri Pinna, and the Battered Women’s Shelter of Summit and Medina Counties for their assistance in data collection.

BIOGRAPHICAL STATEMENTS

Sara Perez, Ph.D., is a post-doctoral fellow in the Department of Psychology at the University of Akron. She completed her Ph.D. at Kent State University. Her research interests include interpersonal violence, PTSD, and their combined impact on psychosocial functioning.

Dawn M. Johnson, Ph.D. is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Akron. She completed her Ph.D. at the University of Kentucky and her postdoctoral work at the Brown University School of Medicine. She has expertise in intimate partner violence, PTSD, and trauma-focused treatment. She currently has NIMH funding where she is evaluating an empowerment-based intervention in the treatment of PTSD in battered women living in shelters.

Caroline Vaile Wright, PhD, is a clinical psychologist in the Department of Psychology at Saint Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, D.C. Her research interests include examining the intersection between mental health and legal interventions to interpersonal trauma.

Footnotes

NOTES

1. The reader is referred to Johnson et al., (2005) for a copy of the entire PPS-R.

Contributor Information

Sara Perez, Department of Psychology, University of Akron, Akron, 44325-4301, 330.972.6821 (ph), 330.972.5549 (fax), sperez@uakron.edu

Dawn M. Johnson, University of Akron, Akron, OH, johndsod@uakron.edu

Caroline Vaile Wright, Saint Elizabeth’s Hospital, Department of Psychology, Washington, D.C., Vaile.wright@dc.gov

REFERENCES

- Bargai N, Ben-Shakhar G, Shalev AY. Posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in battered women: The mediating role of learned helplessness. Journal of Family Violence. 2007;22:267–275. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennice JA, Resick PA, Mechanic M, Astin M. The relative effects of intimate partner physical and sexual violence on posttraumatic stress disorder symptomatology. Violence and Victims. 2003;18:87–94. doi: 10.1891/vivi.2003.18.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman B, Brismar B. A 5-year follow-up study of 117 battered women. American Journal of Public Health. 1991;81:1486–1489. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.11.1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gustman FD, Charney D, Keane TM. The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1995;8:75–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02105408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. 2002;359:1331–1336. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascardi M, O’Leary KD, Schlee KA. Co-occurrence and correlates of posttraumatic stress disorder and major depression in physically abused women. Journal of Family Violence. 1999;14:227–249. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton MA. Empowering and healing the battered woman. Springer; New York: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton MA, Kaltman S, Goodman LA, Weinfurt K, Vankos N. Patterns of intimate partner violence: Correlates and outcomes. Violence & Victims. 2005;20:483–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Cascardi M, Zoellner LA, Feeny NC. Psychological and environmental factors associated with partner violence. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse. 2000;1:67–91. [Google Scholar]

- Foster-Fishman PG, Salem DA, Chibnall S, Legler R, Yapchai C. Empirical support for the critical assumptions of empowerment theory. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1998;26:507–536. [Google Scholar]

- Gondolf EW, Fisher ER. Battered women as survivors: An alternative to treatment learned helplessness. Lexington Books; Lexington, MA.: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Golding J. Intimate partner violence as a risk factor for mental disorders: A meta-analysis. Journal of Family Violence. 1999;14:99–132. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman L, Dutton MA, Vankos N, Weinfurt K. Women’s resource and use of strategies as risk protective factors for reabuse over time. Violence Against Women. 2005;11:311–336. doi: 10.1177/1077801204273297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hathaway JE, Mucci LA, Silverman JG, Brooks DR, Mathews R, Pavlos CA. Health status and health care use of Massachusetts women reporting partner abuse. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 2000;19:302–307. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00236-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist. 1989;44:513–524. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.3.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE, Johnson RJ, Ennis N, Jackson AP. Resource loss, resource gain, and emotional outcomes among inner city women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:632–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE, Lilly RS. Resource conservation as a strategy for community psychology. Journal of Community Psychology. 1993;21:128–148. [Google Scholar]

- Ironson G, Wynings C, Schneiderman N, Baum A, Rodriguez M, Greenwood D, Benight C, Antoni M, LaPierre P, Huang H, Klimas N, Fletcher MA. Posttraumatic stress symptoms, intrusive thoughts, loss, and immune function after Hurricane Andrew. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1997;59:129–141. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199703000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DM, Worell J, Chandler RK. Assessing psychological health and empowerment in women: The Personal Progress Scale Revised. Women and Health. 2005;41:109–129. doi: 10.1300/J013v41n01_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DM, Palmieri PA, Jackson AP, Hobfoll SE. Emotional numbing weakens abused inner-city women’s resiliency resources. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2007;20:197–206. doi: 10.1002/jts.20201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DM, Zlotnick C. A cognitive-behavioral treatment for battered women with PTSD in shelters: Findings from a pilot study. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19 doi: 10.1002/jts.20148. 1-6559-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DM, Zlotnick C. HOPE for battered women with PTSD in domestic violence shelters. Professional Psychology, Research, and Practice. 2009;40:234–241. doi: 10.1037/a0012519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DM, Zlotnick C, Perez S. Is PTSD in battered women associated with psychiatric morbidity, social impairment, and resource loss independent of trauma severity? Behaviour Therapy. 2008:232–241. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones L, Hughes M, Unterstaller U. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in victims of domestic violence: A review of the research. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2001;2:99–119. [Google Scholar]

- Kasturirangan A. Empowerment and programs designed to address domestic violence. Violence Against Women. 2008;14:1465–1475. doi: 10.1177/1077801208325188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp A, Green BL, Hovanitz C, Rawlings EI. Incidence and correlates of posttraumatic stress disorder in battered women: Shelter and community samples. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1995;10:43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp A, Rawlings EI, Green BL. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in battered women: A shelter sample. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1991;4:137–148. [Google Scholar]

- Krause ED, Kaltman S, Goodman LA, Dutton MA. Avoidant coping and PTSD symptoms related to domestic violence exposure: A longitudinal study. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2008;21:83–90. doi: 10.1002/jts.20288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macy RJ, Giattina M, Sangster TH, Crosby C, Montijo NJ. Domestic violence and sexual assault services: Inside the black box. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2009;14:359–373. [Google Scholar]

- Perez S, Johnson DM. PTSD compromises battered women’s future safety. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23:635–651. doi: 10.1177/0886260507313528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport J. Terms of empowerment/exemplar of prevention: Toward a theory for Community Psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1987;15:121–148. doi: 10.1007/BF00919275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riger S. What’s wrong with empowerment? American Journal of Community Psychology. 1993;21:279–292. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AR, Burman S. National survey on empowerment strategies, crisis intervention, and cognitive problem-solving therapy with battered women. In: Roberts AR, editor. Battered women and their families: Intervention strategies and treatment programs. 3rd edition Springer Publishing Company; New York, NY.: 2007. pp. 63–87. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders DG. Posttraumatic stress symptom profiles of battered women: A comparison of survivors in two settings. Violence and Victims. 1994;9:31–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summit County and Medina County Battered Women’s Shelter (SCMCBWS) Battered Women’s Shelter of Summit and Medina Counties. 2009 November 18; Retrieved November 20, 2009 from http://www.scmcbws.org/

- Stein MB, Kennedy C. Major depressive and post-traumatic stress disorder comorbidity in female victims of intimate partner violence. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2001;66:133–138. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00301-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, McCoy SB, Sugarman DB. The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan CM, Gillum T. Shelters and other community-based services for battered women and their children. In: Remzetto CM, Edleson JL, Bergen RK, editors. Sourcebook on Violence Against Women. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA.: 2001. pp. 247–277. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland CA, Bybee DM, Sullivan CI. Beyond bruises and broken bones: The joint effects of stress and injuries on battered women’s health. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2002;30:609–636. doi: 10.1023/A:1016317130710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, Vogt DS, Mechanic MB, Resick PA. Posttraumatic stress disorder and physical health symptoms among women seeking help for relationship aggression. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:354–362. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.3.354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Extent, nature, and consequences of intimate partner violence. US Department of Justice; Washington DC: 2000. NCJ-181867. [Google Scholar]

- Woods S. Intimate partner violence and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in women: What we know and need to know. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2005;20:394–402. doi: 10.1177/0886260504267882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worell J, Remer P. Feminist perspectives in therapy: Empowering diverse women. 2nd ed. Wiley; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman MA. Empowerment theory: Psychological, organizational, and community levels of analysis. In: Rappaport J, Seidman E, editors. Handbook of Community Psychology. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Dordrecht, Netherlands: 2000. pp. 43–63. [Google Scholar]